Abstract

Background

Adiponectin levels have been shown to be associated with colorectal cancer (CRC). Furthermore, a newly identified adiponectin receptor, T-cadherin, has been associated with plasma adiponectin levels. Therefore, we investigated the potential for a genetic association between T-cadherin and CRC risk.

Result

We conducted a case–control study using the Korean Cancer Prevention study-II cohort, which is composed of 325 CRC patients and 977 normal individuals. Study results revealed that rs3865188 in the 5’ flanking region of the T-cadherin gene (CDH13) was significantly associated with CRC (p = 0.0474). The odds ratio (OR) for the TT genotype as compared to the TA + AA genotype was 1.577 (p = 0.0144). In addition, the interaction between CDH13 and the adiponectin gene (APN) for CRC risk was investigated using a logistic regression analysis. Among six APN single nucleotide polymorphisms (rs182052, rs17366568, rs2241767, rs3821799, rs3774261, and rs6773957), an interaction with the rs3865188 was found for four (rs2241767, rs3821799, rs3774261, and rs6773957). The group with combined genotypes of TT for rs3865188 and GG for rs377426 displayed the highest risk for CRC development as compared to those with the other genotype combinations. The OR for the TT/GG genotype as compared to the AA/AA genotype was 4.108 (p = 0.004). Furthermore, the plasma adiponectin level showed a correlation with the gene-gene interaction, and the group with the highest risk for CRC had the lowest adiponectin level (median, 4.8 μg/mL for the TT/GG genotype vs.7.835 μg/mL for the AA/AA genotype, p = 0.0017).

Conclusions

The present study identified a new genetic factor for CRC risk and an interaction between CDH13 and APN in CRC risk. These genetic factors may be useful for predicting CRC risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer in men and the second among women worldwide [1]. While the CRC incidence rates are stabilizing or decreasing in historically-high risk countries, they are increasing in historically low-risk countries [2]. In Korea, the incidence rate of CRC has been continuously growing over the last 10 years, showing 7.0 and 5.3 % annual increases in men and women, respectively [3]. CRC is the third leading cause of cancer death in Korea, and is the only cancer with a mortality rate that has been increasing continuously for the past 10 years, while mortality rates for the top two cancers fallen gradually [3, 4].

The increase in the CRC incidence rate in Korea is thought to be associated with changes towards a Western diet and lifestyle which results in obesity. This is significant, as obesity has been reported to be associated with a high risk for CRC [5–7], and abdominal obesity was shown to be an independent risk factor for colon cancer as well [8]. In obese individuals, plasma adiponectin concentrations are low, and such levels have been shown to be associated with risk for CRC. This implies that decreased expression of adiponectin may be associated with increased risk for CRC development [9, 10].

Adiponectin, an abundant plasma protein exclusively expressed and secreted from adipocytes, modulates metabolic processes including the regulation of glucose levels and fatty acid oxidation. Through these mechanisms, adiponectin suppresses metabolic derangements that may result in type 2 diabetes (T2DM), obesity, atherosclerosis, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and metabolic syndrome. In fact, those with low plasma adiponectin levels are characterized by obesity and T2DM [11, 10]. The results from numerous studies have supported a relationship between plasma adiponectin levels and risk for CRC [12, 10, 13], and variants of the adiponectin gene (APN) have been shown to be associated with CRC risk [14, 15].

As an endogenous insulin sensitizer, adiponectin exerts its action through two G-protein coupled receptors, adiponectin receptor 1 (AdipoR1) and adiponectin receptor 2 (AdipoR2), which are expressed in colonic tissue [16, 17]. Adiponectin has been shown to suppress cell proliferation via activation of AdipoR1 and -R2 mediated 5' adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in colon cancer cells [18]. Additionally, several polymorphisms of APN and AdipoR1 have been shown to be associated with risk for CRC in various populations [19, 14, 20].

Recently, the third member of the adiponectin receptor family, CDH13, was found, and classified as a member of the cell surface glycoprotein family, functioning as a signaling transducer as well as a cell-cell adhesion molecule [21]. Loss of expression and aberrant methylation of the CDH13 gene has been demonstrated in colorectal cancer [22, 23]. However, an association between the CDH13 gene and CRC risk has yet to be described.

In the present study, we identified the nature of the association between CDH13 and CRC, and found that the interaction between APN and CDH13 was related to both the CRC risk and the plasma adiponectin level.

Methods

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants. The study was performed in accordance with the guidelines established by the Catholic Medical Center Office of Human Research Protection Program, and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Catholic University of Korea and Yonsei University.

Study population

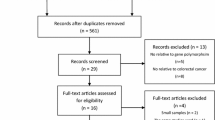

The study population was composed of 325 confirmed CRC patients from the Korean Cancer Prevention study-II (KCP-II), which included 200,595 individuals recruited from 16 health promotion centers nationwide. Patients were categorized as having CRC based on the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O) at the National Cancer Center of Korea [24]. As controls, randomly selected 1004 individuals with lack of CRC based on anamnesis and family history in the KCP-II were genotyped using Human SNP array 5.0 (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and individuals with low genotyping call rates (<95 %) removed. And so were the ones with missing anthropometric measurement (SBP, DBP, waist circumference and BMI) or gender mismatch between genpotype and self-reported information. Thus, 977 normal individuals in the KCP-II were included for the present study [25] (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Genotypes of the control participants were previously determined using the same platform as was used in the present study [25]. Recorded and analyzed clinical characteristics of the participants included age, sex, systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), waist circumference (WC), body mass index (BMI), and plasma adiponectin level. Each participant was measured for weight and height while wearing light clothing, and BMI was calculated as mass (kg) divided by height in meters squared (m2). SBP and DBP were measured after a 15 min rest. Serum was separated from peripheral venous blood and the adiponectin level was measured using an ELISA kit following the manufacturer’s protocol (Mesdia, Korea) [26].

Genotyping and single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) selection

Genomic DNA isolated from the peripheral blood of participants was utilized for genotyping using the Human SNP Array 5.0 (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) at DNAlink Inc. (Seoul, Korea). For data accuracy, an internal quality control (QC) measurement was used: QC call rate (dynamic model algorithm) always exceeded > =86 %, and contrast QC <0.4. The heterozygosity of X chromosome markers identified the sex of each sample. Genotype calling was accomplished using the Birdseed (v2) algorithm. The genotype call rate for six APN SNPs (rs182052, rs17366568, rs2241767, rs3821799, rs3774261, and rs6773957) and one CDH13 SNP (rs3865188) were all above 95 %.

The single CDH13 SNP (rs3865188) was selected due to its previously identified association with plasma adiponectin levels [27]. In addition, all SNPs in APN on the chip were analyzed. The linkage disequilibrium (LD) between the APN SNPs was determined using Haploview 4.2 (Additional file 2: Figure S2).

Statistical analysis

The T-test or X 2 test was used to examine the differences in the distribution of demographic and clinical characteristics, as well as genotype frequencies between cases and controls. Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was also analyzed using the X 2 test. A logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate the CRC risk associated with the genotype of each SNP, as well as the interactions between genotypes in comparison to control participants. The odds ratio (OR) and 95 % confidence intervals (CI) of CRC associated with CDH13 and APNSNP genotypes was computed and adjusted for age, sex, and BMI. The T-test and analysis of variance test were used for normally distributed variables. Nonparametric tests included the Wilcoxon signed rank test and the Kruskal-Wallis test. All tests were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software (ver. 9.2).

Results

General characteristics of study participants

The distribution of the demographic and clinical characteristics of the 325 CRC patients and 977 controls are shown in Table 1. The CRC patients were older with a greater proportion of males than the control group. They also had higher SBP, DBP, and BMI, and thicker WCthan controls. However, no difference in adiponectin levels was found between cases and controls.

Associations between SNPs and CRC

The genotype distributions of all SNPs were in HWE in the control group (Additional file 3: Table S1, p > 0.2). A significant association was found only between the CDH13 SNP rs3865188 and CRC; none of the six APN SNPs showed evidence of any association with CRC. The frequencies of rs3865188 AA, AT, and TT genotypes were 0.4646, 0.3815, and 0.1538, respectively, in patients as compared to 0.4862, 0.4104, and 0.1034, respectively, in controls (p = 0.0474; Table 2). The logistic regression analysis revealed that the individuals with an rs3865188 TT genotype had an increased risk of developing CRC as compared to the individuals with the other genotypes (AT or AA) in the recessive mode only (OR = 1.577, 95 % CI 1.095–2.272, p = 0.0144; Table 3). The risk estimate remained significant after adjustment for age and BMI, and showed a tendency toward risk even after an additional adjustment for sex (Table 3).

Gene-gene interaction for CRC risk

Whether the presence of both variants could influence the risk for CRC was determined between rs3865188 and each of the six APN SNPs. Among the six SNPs, fourshowed an interaction with rs3865188 such that the combined genotypes were significantly associated with CRC risk. Those four SNPs, rs2241767, rs3821799, rs3774261, and rs6773957, formed an LD block (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Among individuals with an rs3865188TT genotype, a significant change in CRC risk was not observed for individuals who carried wild type alleles for all four SNPs when compared to controls. In contrast, among those with an rs3865188 TT genotype, those whose genotypes were homozygous for the variant allele for each SNP had a much higher risk for CRC development as compared to the other genotype combinations (Fig. 1).

Adjusted odds ratios for colorectal cancer risk by interaction between rs3865188 and each of the four APN SNPs. a rs3865188-rs3774261 interaction, *; p = 0.004, b) rs3865188-rs2241767 interaction, †; p = 0.0402, c) rs3865188-rs3821799 interaction,‡; p = 0.0163, d) rs3865188-rs6773957 interaction,₤; p = 0.0064. Adjusted for age, sex and BMI

Individuals with the combined genotype of TT for rs3865188 and GG for rs3774261 had the most significantly increased CRC risk as compared to those with the other genotype combinations (Fig. 1a, OR = 4.108, 95 % CI 1.568–10.763, p = 0.004). Risks for CRC development due to interaction with rs3865188 were also increased with rs2241767 (Fig. 1b, OR = 2.495, 95 % CI 1.042–5.943, p = 0.0402), rs3821799 (Fig. 1c, OR = 3.491, 95 % CI 1.259–9.679, p = 0.0163), and rs6773957 (Fig. 1d, OR = 3.954, 95 % CI 1.471–10.629, p = 0.0064). However, rs182052 and rs17366568 were neither associated with CRC independently nor interacted with rs3865188 for CRC risk.

Correlation of the combined genotype with the adiponectin level

Because rs3865188 was shown to be associated with the plasma level of adiponectin, and low levels of adiponectin were reported to be related to CRC risk [27], we investigated whether an association with CRC by gene-gene interaction was correlated with the plasma adiponectin level. The plasma adiponectin level was analyzed using nonparametric tests.

The plasma adiponectin level was significantly lower in the groups with the risk genotype combination than in those with the other genotype combinations for all SNP pairs. Individuals with a TT genotype for rs3865188 and a GG genotype for rs3774261 had the lowest plasma adiponectin levels as compared to those with the AA genotype for rs3865188 and the AA genotype for rs3774261 (Fig. 2, rs3865188:AA/rs3774261:AA median = 7.83 μg/ml, rs3865188:TT/rs3774261:GG median = 4.80 μg/ml, p = 0.0017). A similar pattern was seen in the pairs of other genotype combinations (Additional file 3: Table S2).

Discussion

This is the first study to examine gene-gene interactions between genetic variants of adiponectin and its new receptor, CDH13, with reference to CRC. Additionally, the present study also demonstrated the significant gene-gene interactions betweenCDH13 rs3865188 and APN SNPs in a LD block in relation to the risk for CRC, with the combination of the rs3865188 TT and rs3774261 GG genotypes having the highest risk. Of interest, this risk increase was consistent with low adiponectin levels.

Adiponectin and its pathway have been implicated in the carcinogenesis of multiple cancers including CRC [28]. Adiponectin has been associated with metabolic syndrome, T2DM, and obesity [29–31], which are known risk factors for CRC [7, 32]. The results from several studies have indicated that adiponectin mRNA and plasma levels were decreased in patients with obesity and T2DM [33, 34], implicating adiponectin as a key player in the development of obesity and insulin resistance. Because this characteristic of adiponectinis attributable to carcinogenesis, the roles of adiponectin and its receptors have been studied in carcinogenesis [35–37].

APN SNPs have been controversial in CRC carcinogenesis association studies, as no single SNP has been consistently associated across the different studies [38–40]. While the APN gene was found not to be associated with CRC in the UK and US (New York) [38, 39], contrary results were found in a Chinese population [38]. The most recent large meta-analysis on the subject revealed that rs2241766 alone showed an association with CRC in a specific genetic mode. In our study, none of the six APN SNPs were associated with either CRC risk or adiponectin levels. The rs3774261 and rs6773957APN SNPs were shown to be associated with adiponectin levels in an American population [41]. Furthermore, rs1063538, which is in LD with these two SNPs was shown to have an association with CRC risk in a Chinese population [40]. The rs3774261 and rs6773957 SNPs had lower p-values than the other four SNPs, however, no associations with CRC risk or adiponectin levels were found in our study. Instead, we documented that these SNPs showed gene-gene interactions with rs3865188 for CRC risk and adiponectin levels. Thus, a replication study with larger sample is required to clarify the nature of the relationship between APN variants and CRC risk in Koreans. Interestingly, four SNPs (rs2241767, rs3821799, rs3774261, and rs6773957) of the six APN SNPs formed an identical LD block in the Eastern Asians including Korean population, CHB; Han Chinese in Bejing, China, JPT; Japanese in Tokyo, Japan, whereas those did not in Caucasians such as CEU; Utah Residents with Northern and Western European Ancestry (HapMap project). Furthermore, it has been shown that rs3865188 is also highly associated with plasma APN levels in Filipinos, and Japanese as well [42, 43]. Thus, there is a possibility that gene-gene interaction between a CDH13 SNP and adiponectin SNPs may affect East Asians and a further study is required to clarify this relationship.

CRC risk is mediated through APN receptors, as well as through APN. The results of a previous study using classification and regression tree analysis indicated that an environmental factor was associated with risk for CRC based on the interaction between rs1063538 of APN and rs1539355 of AdipoR1 [40]. Results from an additional study demonstrated that adiponectin mediated AMPK activity via AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 in a colon cancer cell line [18]. AMPK plays critical roles in the regulation of glucose metabolism, insulin sensitivity, and lipid metabolism [44], all of which are correlated with tumorigenesis in humans [45]. Additionally, polymorphisms related to insulin resistance and obesity have been reported to be associated with CRC risk [46]. Thus, we anticipated that a receptor gene of APN may play an important role in the carcinogenesis of CRC.

Although we observed a marginal association of a CDH13 polymorphism and no association of APN polymorphisms with CRC, the interaction of these SNPs showed significant associations with the risk of CRC, suggesting that APN function via CDH13 should be considered in regard to CRC risk.

CDH13 expression was found in adult brain, lung, heart and blood vessels [47] and shown to be modulated by various factors such as FGF-2 [48], oxidative stress [49], progesterone, estradiol and serum factors [50], and zeb1 [51]. However, CDH13 expression in different ethnic groups has not been currently known.

The biological function of CDH13 remains largely unknown. However, it is a known APN receptor, and binding of the high molecular weight form of APN to CDH13 transduces signals and activates AMPK activity [44]. Furthermore, CDH13 is known to function as a tumor suppressor gene, and suppression of CDH13 expression by aberrant methylation in the CpG island of its promoter has been reported in CRC [23, 52] and other types of cancers [53–55]. Thus, we suggest that pathological regulation affected by the interaction between CDH13 and APN may be mediated through AMPK in CRC.

Epidemiologic studies have identified sexual dimorphism in CRC risk, with a higher incidence and earlier onset in men [56] and female hormones have been suggested to play a protective role in CRC development [57]. Interestingly, we observed that rs3865188of CDH13was significantly associated with CRC risk in male (p = 0.049) but not in female (p = 0.880). Recently, circulating T-cadherin and high molecular weight adiponecin levels were shown to be negatively associated in angiographically stable coronary artery young male patients but not in female patients [58]. Therefore, male-specific CDH13 association in CRC risk could have a sex-specific contributing factor(s) involved. Clearly, further study with larger number of participantsis required to identify an underlying factor for this observation.

The present study was not without limitations. First, our sample size was limited. We selected 325 CRC patients and 977 normal individuals from the KCP-II. Further study will be needed in order to analyze more Koreans and members of other ethnic groups. Second, our study only identified interactions between genetic factors with respect to CRC risk, and therefore we did not investigate relationships between genetic factors and clinical information (cancer staging, drug treatment, other disorder). Additional studies will be required in order to more fully elucidate the nature of the correlations between clinical information, CRC, and gene-gene interactions.

Conclusion

Nevertheless, we found a new gene-gene interaction with respect to CRC risk is uncovered, and identified a correlation between adiponectin level and the combined genotype. Our study suggests that gene-gene interaction between a CDH13 SNP and adiponectin SNPs is a CRC risk genetic marker for predisposition in Korean population.

Abbreviations

- CRC:

-

Colorectal cancer

- SNP:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- KCP-II:

-

Korean Cancer Prevention study-II

- CDH13 :

-

T-cadherin gene

- APN :

-

Adiponectin gene

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- 95 % CI:

-

95 % confidence intervals

- LD:

-

Linkage disequilibrium

- HWE:

-

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium

- ICD-O:

-

The International Classification of Diseases for Oncology

- QC:

-

Quality control

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- DBP:

-

Diastolic blood pressure

- WC:

-

Waist circumference

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- T2DM:

-

Type 2 diabetes

- AdipoR1 :

-

Adiponectin receptor 1

- AdipoR2 :

-

Adiponectin receptor 2

- AMPK:

-

5' adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase

References

Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(12):2893–917. doi:10.1002/ijc.25516.

Jemal A, Center MM, DeSantis C, Ward EM. Global patterns of cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(8):1893–907. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0437.

Jung KW, Park S, Kong HJ, Won YJ, Lee JY, Park EC, et al. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2008. Cancer Res Treat. 2011;43(1):1–11. doi:10.4143/crt.2011.43.1.1.

Shin A, Joo J, Bak J, Yang HR, Kim J, Park S, et al. Site-specific risk factors for colorectal cancer in a Korean population. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e23196. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023196.

Calle EE, Kaaks R. Overweight, obesity and cancer: epidemiological evidence and proposed mechanisms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(8):579–91. doi:10.1038/nrc1408.

Basen-Engquist K, Chang M. Obesity and cancer risk: recent review and evidence. Curr Oncol Rep. 2011;13(1):71–6. doi:10.1007/s11912-010-0139-7.

Bardou M, Barkun AN, Martel M. Obesity and colorectal cancer. Gut. 2013;62(6):933–47. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304701.

Frezza EE, Wachtel MS, Chiriva-Internati M. Influence of obesity on the risk of developing colon cancer. Gut. 2006;55(2):285–91. doi:10.1136/gut.2005.073163.

Arita Y, Kihara S, Ouchi N, Takahashi M, Maeda K, Miyagawa J, et al. Paradoxical decrease of an adipose-specific protein, adiponectin, in obesity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;257(1):79–83.

Wei EK, Giovannucci E, Fuchs CS, Willett WC, Mantzoros CS. Low plasma adiponectin levels and risk of colorectal cancer in men: a prospective study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(22):1688–94. doi:10.1093/jnci/dji376.

Weyer C, Funahashi T, Tanaka S, Hotta K, Matsuzawa Y, Pratley RE, et al. Hypoadiponectinemia in obesity and type 2 diabetes: close association with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(5):1930–5.

Erarslan E, Turkay C, Koktener A, Koca C, Uz B, Bavbek N. Association of visceral fat accumulation and adiponectin levels with colorectal neoplasia. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54(4):862–8. doi:10.1007/s10620-008-0440-6.

Otake S, Takeda H, Suzuki Y, Fukui T, Watanabe S, Ishihama K, et al. Association of visceral fat accumulation and plasma adiponectin with colorectal adenoma: evidence for participation of insulin resistance. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(10):3642–6. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1868.

Kaklamani VG, Wisinski KB, Sadim M, Gulden C, Do A, Offit K, et al. Variants of the adiponectin (ADIPOQ) and adiponectin receptor 1 (ADIPOR1) genes and colorectal cancer risk. JAMA. 2008;300(13):1523–31. doi:10.1001/jama.300.13.1523.

Partida-Perez M, de la Luz Ayala-Madrigal M, Peregrina-Sandoval J, Macias-Gomez N, Moreno-Ortiz J, Leal-Ugarte E, et al. Association of LEP and ADIPOQ common variants with colorectal cancer in Mexican patients. Cancer Biomark. 2010;7(3):117–21. doi:10.3233/CBM-2010-0154.

Drew JE, Farquharson AJ, Padidar S, Duthie GG, Mercer JG, Arthur JR, et al. Insulin, leptin, and adiponectin receptors in colon: regulation relative to differing body adiposity independent of diet and in response to dimethylhydrazine. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;293(4):G682–91. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.00231.2007.

Williams CJ, Mitsiades N, Sozopoulos E, Hsi A, Wolk A, Nifli AP, et al. Adiponectin receptor expression is elevated in colorectal carcinomas but not in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2008;15(1):289–99. doi:10.1677/ERC-07-0197.

Kim AY, Lee YS, Kim KH, Lee JH, Lee HK, Jang SH, et al. Adiponectin represses colon cancer cell proliferation via AdipoR1- and -R2-mediated AMPK activation. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24(7):1441–52. doi:10.1210/me.2009-0498.

He B, Pan Y, Zhang Y, Bao Q, Chen L, Nie Z, et al. Effects of genetic variations in the adiponectin pathway genes on the risk of colorectal cancer in the Chinese population. BMC Med Genet. 2011;12:94. doi:10.1186/1471-2350-12-94.

Yi N, Kaklamani VG, Pasche B. Bayesian analysis of genetic interactions in case–control studies, with application to adiponectin genes and colorectal cancer risk. Ann Hum Genet. 2011;75(1):90–104. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2010.00605.x.

Ivanov D, Philippova M, Antropova J, Gubaeva F, Iljinskaya O, Tararak E, et al. Expression of cell adhesion molecule T-cadherin in the human vasculature. Histochem Cell Biol. 2001;115(3):231–42.

Toyooka S, Toyooka KO, Harada K, Miyajima K, Makarla P, Sathyanarayana UG, et al. Aberrant methylation of the CDH13 (H-cadherin) promoter region in colorectal cancers and adenomas. Cancer Res. 2002;62(12):3382–6.

Hibi K, Nakayama H, Kodera Y, Ito K, Akiyama S, Nakao A. CDH13 promoter region is specifically methylated in poorly differentiated colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2004;90(5):1030–3. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6601647.

Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare. The National Cancer Registry, The National Cancer Registry. Seoul: Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2007.

Jo J, Nam CM, Sull JW, Yun JE, Kim SY, Lee SJ, et al. Prediction of Colorectal Cancer Risk Using a Genetic Risk Score: The Korean Cancer Prevention Study-II (KCPS-II). Genomics Inform. 2012;10(3):175–83. doi:10.5808/gi.2012.10.3.175.

Yoon SJ, Lee HS, Lee SW, Yun JE, Kim SY, Cho ER, et al. The association between adiponectin and diabetes in the Korean population. Metabolism. 2008;57(6):853–7. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2008.01.031.

Jee SH, Sull JW, Lee JE, Shin C, Park J, Kimm H, et al. Adiponectin concentrations: a genome-wide association study. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87(4):545–52. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.09.004.

Dalamaga M, Diakopoulos KN, Mantzoros CS. The role of adiponectin in cancer: a review of current evidence. Endocr Rev. 2012;33(4):547–94. doi:10.1210/er.2011-1015.

Fasshauer M, Paschke R, Stumvoll M. Adiponectin, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. Biochimie. 2004;86(11):779–84. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2004.09.016.

Matsuzawa Y, Funahashi T, Kihara S, Shimomura I. Adiponectin and metabolic syndrome. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(1):29–33. doi:10.1161/01.ATV.0000099786.99623.EF.

Kadowaki T, Yamauchi T, Kubota N, Hara K, Ueki K, Tobe K. Adiponectin and adiponectin receptors in insulin resistance, diabetes, and the metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(7):1784–92. doi:10.1172/JCI29126.

Giovannucci E. Insulin, insulin-like growth factors and colon cancer: a review of the evidence. J Nutr. 2001;131(11 Suppl):3109S–20S.

Halleux CM, Takahashi M, Delporte ML, Detry R, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y, et al. Secretion of adiponectin and regulation of apM1 gene expression in human visceral adipose tissue. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;288(5):1102–7. doi:10.1006/bbrc.2001.5904.

Hotta K, Funahashi T, Arita Y, Takahashi M, Matsuda M, Okamoto Y, et al. Plasma concentrations of a novel, adipose-specific protein, adiponectin, in type 2 diabetic patients. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20(6):1595–9.

Kaklamani V, Yi N, Zhang K, Sadim M, Offit K, Oddoux C, et al. Polymorphisms of ADIPOQ and ADIPOR1 and prostate cancer risk. Metabolism. 2011;60(9):1234–43. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2011.01.005.

Dhillon PK, Penney KL, Schumacher F, Rider JR, Sesso HD, Pollak M, et al. Common polymorphisms in the adiponectin and its receptor genes, adiponectin levels and the risk of prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(12):2618–27. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0434.

Kaklamani VG, Sadim M, Hsi A, Offit K, Oddoux C, Ostrer H, et al. Variants of the adiponectin and adiponectin receptor 1 genes and breast cancer risk. Cancer Res. 2008;68(9):3178–84. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0533.

Gornick MC, Rennert G, Moreno V, Gruber SB. Adiponectin gene and risk of colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(4):562–4. doi:10.1038/bjc.2011.259.

Carvajal-Carmona LG, Spain S, Kerr D, Houlston R, Cazier JB, Tomlinson I. Common variation at the adiponectin locus is not associated with colorectal cancer risk in the UK. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18(10):1889–92. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddp109.

Liu L, Zhong R, Wei S, Yin JY, Xiang H, Zou L, et al. Interactions between genetic variants in the adiponectin, adiponectin receptor 1 and environmental factors on the risk of colorectal cancer. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e27301. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0027301.

Ling H, Waterworth DM, Stirnadel HA, Pollin TI, Barter PJ, Kesaniemi YA, et al. Genome-wide linkage and association analyses to identify genes influencing adiponectin levels: the GEMS Study. Obesity. 2009;17(4):737–44. doi:10.1038/oby.2008.625.

Wu Y, Li Y, Lange EM, Croteau-Chonka DC, Kuzawa CW, McDade TW, et al. Genome-wide association study for adiponectin levels in Filipino women identifies CDH13 and a novel uncommon haplotype at KNG1-ADIPOQ. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19(24):4955–64. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddq423.

Morisaki H, Yamanaka I, Iwai N, Miyamoto Y, Kokubo Y, Okamura T, et al. CDH13 gene coding T-cadherin influences variations in plasma adiponectin levels in the Japanese population. Hum Mutat. 2012;33(2):402–10. doi:10.1002/humu.21652.

Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Minokoshi Y, Ito Y, Waki H, Uchida S, et al. Adiponectin stimulates glucose utilization and fatty-acid oxidation by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Nat Med. 2002;8(11):1288–95. doi:10.1038/nm788.

Schoen RE, Tangen CM, Kuller LH, Burke GL, Cushman M, Tracy RP, et al. Increased blood glucose and insulin, body size, and incident colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91(13):1147–54.

Gunter MJ, Leitzmann MF. Obesity and colorectal cancer: epidemiology, mechanisms and candidate genes. J Nutr Biochem. 2006;17(3):145–56. doi:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2005.06.011.

Lee SW. H-cadherin, a novel cadherin with growth inhibitory functions and diminished expression in human breast cancer. Nat Med. 1996;2(7):776–82.

Adachi Y, Takeuchi T, Sonobe H, Ohtsuki Y. An adiponectin receptor, T-cadherin, was selectively expressed in intratumoral capillary endothelial cells in hepatocellular carcinoma: possible cross talk between T-cadherin and FGF-2 pathways. Virchows Arch. 2006;448(3):311–8. doi:10.1007/s00428-005-0098-9.

Joshi MB, Philippova M, Ivanov D, Allenspach R, Erne P, Resink TJ. T-cadherin protects endothelial cells from oxidative stress-induced apoptosis. FASEB J. 2005;19(12):1737–9. doi:10.1096/fj.05-3834fje.

Bromhead C, Miller JH, McDonald FJ. Regulation of T-cadherin by hormones, glucocorticoid and EGF. Gene. 2006;374:58–67. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2006.01.013.

Adachi Y, Takeuchi T, Nagayama T, Ohtsuki Y, Furihata M. Zeb1-mediated T-cadherin repression increases the invasive potential of gallbladder cancer. FEBS Lett. 2009;583(2):430–6. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2008.12.042.

Lofton-Day C, Model F, Devos T, Tetzner R, Distler J, Schuster M, et al. DNA methylation biomarkers for blood-based colorectal cancer screening. Clin Chem. 2008;54(2):414–23. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2007.095992.

Takeuchi T, Liang SB, Matsuyoshi N, Zhou S, Miyachi Y, Sonobe H, et al. Loss of T-cadherin (CDH13, H-cadherin) expression in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Lab Invest. 2002;82(8):1023–9.

Ulivi P, Zoli W, Calistri D, Fabbri F, Tesei A, Rosetti M, et al. p16INK4A and CDH13 hypermethylation in tumor and serum of non-small cell lung cancer patients. J Cell Physiol. 2006;206(3):611–5. doi:10.1002/jcp.20503.

Sakai M, Hibi K, Koshikawa K, Inoue S, Takeda S, Kaneko T, et al. Frequent promoter methylation and gene silencing of CDH13 in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Sci. 2004;95(7):588–91.

Potter JD, Slattery ML, Bostick RM, Gapstur SM. Colon cancer: a review of the epidemiology. Epidemiol Rev. 1993;15(2):499–545.

Chlebowski RT, Wactawski-Wende J, Ritenbaugh C, Hubbell FA, Ascensao J, Rodabough RJ, et al. Estrogen plus progestin and colorectal cancer in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(10):991–1004. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa032071.

Schoenenberger AW, Pfaff D, Dasen B, Frismantiene A, Erne P, Resink TJ, et al. Gender-Specific Associations between Circulating T-Cadherin and High Molecular Weight-Adiponectin in Patients with Stable Coronary Artery Disease. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0131140. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0131140.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the National R&D Program for Cancer Control, Ministry for Health, Welfare and Family affairs, Republic of Korea (1220180). This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program throuth the National Research Foundation of Korea(NRF) funded by the Minstry of Education, Science and Technology (NRF-2013R1A1A2011821 and 2012R1A5A2047939).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JP: genetic studies, wrote and revised the manuscript, IK: collected samples and genetics studies, KJ: collected samples, SK: collected samples, SHJ:collected samples and design of study, SKY: design of study, contributed to manuscript preparation and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Sun Ha Jee and Sungjoo Kim Yoon contributed equally to this work.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Overall study population design. (TIFF 1061 kb)

Additional file 2: Figure S2.

Linkage disequilibrium of six SNPs of the adiponectin gene (APN). (TIFF 599 kb)

Additional file 3: Table S1.

Hardy-weinberg equilibrium (HWE) in the control group. Table S2. Differences on the adiponectin level in KCP-II based on the genotype combination between rs3865188- rs2241767, rs3865188- rs382179 and rs3865188- rs6773957. (DOCX 18 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, J., Kim, I., Jung, K.J. et al. Gene-gene interaction analysis identifies a new genetic risk factor for colorectal cancer. J Biomed Sci 22, 73 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12929-015-0180-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12929-015-0180-9