Abstract

Background

Epidemiological studies have suggested that variants on adiponectin (ADIPOQ) and its receptor ADIPOR1 (adiponectin receptor 1) are associated with colorectal cancer (CRC) risk; however, the results were inconclusive. The aim of the study was to evaluate the associations between the variants on ADIPOQ and ADIPOR1 and the CRC risk with a hospital-based case-control study in the Chinese population along with meta-analysis of available epidemiological studies.

Methods

With a hospital-based case-control study of 341 cases and 727 controls, the associations between the common variants on ADIPOQ (rs266729, rs822395, rs2241766 and rs1501299) and ADIPOR1 (rs1342387 and rs12733285) and CRC susceptibility were evaluated. Meta-analysis of the published epidemiological studies was performed to investigate the associations between the variants and CRC risk.

Results

For the population study, we found that variant rs1342387 of ADIPOR1 was associated with a reduced risk for CRC [adjusted odds ratio (OR) = 0.74, 95% confidential intervals (95% CI) = 0.57-0.97; CT/TT vs. CC]. The meta-analysis also suggested a significant association for rs1342387 and CRC risk; the pooled OR was 0.79 (95% CI = 0.66-0.95) for the CT/TT carriers compared to CC homozygotes under the random-effects model (Q = 8.06, df = 4, P = 0.089; I2 = 50.4%). The case-control study found no significant association for variants rs266729, rs822395, rs2241766, and rs1501299 on ADIPOQ or variant rs12733285 on ADIPOR1 and CRC susceptibility, which were consistent with results from the meta-analysis studies.

Conclusions

These data suggested that variant rs1342387 on ADIPOR1 may be a novel CRC susceptibility factor.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Along with the increasing incidence of the obesity and the mortality rate of the obesity related diseases worldwide, hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance that are likely to confer an increased risk of colorectal cancer (CRC) have drawn more attention [1]. Epidemiological studies found that several markers for insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia, including high blood insulin, glucose, IGF-1, and C-peptide levels, are associated with the increased CRC risk [2]. Adiponectin (ADIPOQ), an insulin sensitizer secreted principally by adipocytes, is inversely associated with body fat, obesity, insulin resistance through the stimulation of insulin secretion, increment of fatty acid combustion and energy consumption [3]. Prospective studies demonstrated that an elevated adiponectin level was associated with the reduced risk of CRC in men [4], suggested that adiponectin and its downstream signaling pathways may be involved in the development of CRC.

Two adiponectin receptors (ADIPOR1 and ADIPOR2) mediate the biological activities of adiponectin in the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase activities, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, which lead to the enhanced fatty-acid oxidation in skeletal muscle cells [5]. ADIPOR1 is abundantly expressed in skeletal muscle cells, while ADIPOR2 is predominantly expressed in the liver cells [6]. Interestingly, adiponectin receptors are also found to be expressed in human malignant cells, including colorectal cancer, breast cancer, and prostate cancer etc., and they mediate the anticancer activities of adiponectin in the cells. ADIPOQ gene deficient mice showed an increased incidence of colon polyps in relative to wild-type mice when they were fed with a high-fat diet [7]. ADIPOQ deficiency mice also show the enhanced colorectal carcinogenesis and hepatocellular carcinoma formation activities induced by azoxymethane [8]. It was suggested that ADIPOR1 is more important than the ADIPOR2 in the regulation of the anticancer activities of ADIPOQ, as an increment in epithelial cell proliferation in ADIPOR1-deficient mice but not in ADIPOR2-deficient mice was found [7].

Since there are potential protective effects of ADIPOQ and ADIPOR1 against colorectal carcinogenesis, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) on genes ADIPOQ and ADIPOR1 may contribute to the susceptibility to CRC. Kaklamani et al. firstly evaluated the associations between the variants of ADIPOQ and ADIPOR1 with CRC risk in a two-stage case-control study [9]. They found a variant, rs266729 (C > G) on ADIPOQ, was associated with a reduced risk of CRC [9]. However, subsequent studies performed in other populations did not find such association [10]-[13]. Kaklamani et al. also found a significant association with CRC risk for rs822396 (ADIPOQ), rs822395 (ADIPOQ), and rs1342387 (ADIPOR1) in their first-stage study; however, no significant association was found for these variants in the second-stage study [9]. He et al. found two variants (rs1342387 and rs12733285) on ADIPOR1 were associated with CRC risk, but not for rs266729 [12]. Liu et al. found no significant association for the above mentioned variants, but they identified a novel SNP, rs1063538, on ADIPOQ that may contribute to CRC susceptibility [13]. Other widely evaluated loci on ADIPOQ and their associations with the CRC risk including the rs2241766, which leads to a synonymous mutation of the amino acid for ADIPOQ protein, and rs1501299 (+276 G > T); however, no conclusive results found [9],[12],[13].

In the current study, we further evaluated the associations between the variants of ADIPOQ and ADIPOR1 and the colorectal cancer in a southeast Chinese population. As inconsistent results were found for studies evaluated the associations between variants on ADIPOQ or ADIPOR1 and CRC risk, we also performed the meta-analysis studies of the published epidemiological studies to systematically evaluate the associations between variants of ADIPOQ and ADIPOR1 and the CRC risk.

Methods

Study populations

All the participants recruited in the current study have been described previously [14]. In briefly, a total of 341 CRC patients and 727 controls with the qualified DNA sample were included. The cases were patients who received the clinic treatments between 2001 and 2003 (aged between 30 and 80 years old) at three hospitals (Xi'nan Hospital, Xinqiao Hospital and Daping Hospital) in Chongqing City, China. All the cases were from Chongqing or the surrounding regions (including the Sichuan, Yunnan, and Guizhou provinces in the southwest of China) and histopathologically diagnosed with primary CRC for the first time within the past six months. No pre-treatment were performed at the time of recruitment for the participants. The controls were recruited from the Departments of General Surgery, Orthopedics, or Trauma who received the clinic treatments for trauma, bone fracture, appendicitis, arthritis, or varicose vein in the same hospitals. The controls were matched with the cases by age (±5 years), sex, and residence. The participants were recruited following the guidelines of the Japan, Korea, and China Colorectal Cancer Collaboration Group. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committees of the participating hospitals, including the “Ethics Committee of Xi'nan Hospital”, the “Ethics Committee of Xinqiao Hospital” and the “Ethics Committee of Daping Hospital”. All participants have provided a written informed consent and completed a structured questionnaire regarding their basic characteristics as previously reported [14].

SNP selection and genotyping

Four most widely studied SNPs on ADIPOQ (including rs2241766, rs266729, rs822395 and rs1501299) and two on ADIPOR1 (including rs12733285 and rs1342387) were selected to evaluate their associations with CRC risk. Genomic DNA was extracted with the Promega DNA Purification Wizard kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions and was stored at -20°C until use. Genotyping of the selected SNPs was performed using the Taqman-MGB probes for SNP allelic discrimination with a 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems Incorporated, USA). All of the primers and probes were designed with Primer Express v3.0 (Applied Biosystems Incorporated, USA) and synthesized by the Shanghai GeneCore BioTechnologies Co., Ltd (Additional file 1 Table S1) [15]. The results were ascertained using SDS software version 2.3 (Applied Biosystems Incorporated, USA). 10% of samples were randomly selected to assess the reproducibility of the genotyping results, resulting in a more than 99% concordance.

Meta-analysis of the associations between the selected variants with CRC risk

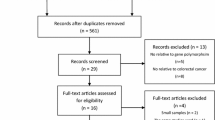

To assess the associations between the selected SNPs of ADIPOQ and ADIPOR1 with CRC risk, we performed a comprehensive and systematic search of PubMed and MEDLINE databases (updated to June, 2014), with the terms of “adiponectin,” “ADIPOQ,” “adiponectin receptor 1,” and “ADIPOR1” in combination with “colorectal cancer,” “colon cancer,” or “rectal cancer.” The goal was to identify studies that have evaluated the associations between the selected variants on the two genes and CRC risk. All the references from the identified studies were checked to identify any missing studies. The identified reports were thoroughly examined to exclude potential studies with overlapping populations. For those studies with overlapping samples, the one with the largest sample size and/or provided the detailed information about the genotype information for the participants was included in the meta-analysis. Studies were included only if they had evaluated the associations between the selected variants and CRC risk and provided sufficient information about the frequency of the genotypes in cases and controls. When there were sub-group studies or multiple study stages in the reports, they were considered as individual studies. The eligibility studies included were case-control, cohort, or cross-sectional studies that reported in the English language. The working flow chart for identification of eligible studies is shown in Figure 1.

For each report, the following information was extracted: first author, publication year, study type, study location, total number of cases and controls, and the allele frequency of the participants.

Statistical methods

Differences in demographic characteristics were evaluated by the χ2 test (for categorical variables) and Student’s t-test (for continuous variables). The Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was assessed by the χ2 test [one degree of freedom (d.f)] [16]. The prevalence of the genotypes for each variant was measured in cases and controls, and the associations between ADIPOQ or ADIPOR1 genotypes and risk of CRC were estimated by computing odds ratios (ORs) and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). The common homozygotes were recognized as references under the unconditional logistic regression statistical model with or without adjustments for covariants age, sex, drinking habit, and smoking status. The additive and the dominant genetic models were used to evaluate the associations between the variants and CRC risk. The false discovery rate (FDR) test was also performed to adjust the P-values for the multiple testing of the selected variants.

For the meta-analysis, the pooled OR and its 95% CI for the dominant genetic effect model of the selected variants were calculated using the standard inverse variance weighting method for the fixed-effects model and the DerSimonian-Laird method for the random-effects model. Heterogeneity between studies was assessed using the Cochrane’s Q-test together with the I2 statistic. Heterogeneity between the studies was considered significant when P < 0.1 for the Q-test or the I2 value was more than 25%. If significant heterogeneity between studies was found, the overall pooled estimate under the random-effects model rather than the fixed-effects model was acceptable. Publication bias was graphically represented by funnel plotting and was further assessed by Egger’s linear regression test [17]. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to evaluate the influence of individual studies on overall estimates by sequential removal of each individual study. Statistical analyses were accomplished using R Software and the SNPassoc and Meta packages (http://www.r-project.org/).

Results

Patient characteristics

The characteristics of the participants recruited are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the CRC cases was slightly greater than that for the control participants (P = 0.01, Table 1). Consistent with previous reports [14],[18], more CRC patients had a higher daily average alcohol intake (>15 g/day) than the controls (P = 0.023, Table 1). Other potential confounders, including sex and smoking status, were not significantly different between the cases and controls (Table 1). No significant difference was also found for the percentage of the cases and controls recruited from the three hospitals (P = 0.545, Table 1).

Results for genotyping

The genotyping results of the selected SNPs in the CRC cases and controls are shown in Table 2. The overall call rate for each SNP was > 96%, and none of the selected SNPs was deviate from the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium test (P > 0.05, Table 2). Of the six genotyped SNPs, only rs1342387 showed a significant association with CRC risk (adjusted OR = 0.80, 95% CI = 0.60-1.06 for CT vs. CC and adjusted OR = 0.59, 95% CI = 0.38-0.89 for TT vs. CC; P-trend = 0.009). Under the dominant model, the allele T carriers showed a significant decreased risk of CRC (adjusted OR = 0.74, 95% CI = 0.57-0.97; P = 0.028) in relative to the common CC carriers (Table 2). After the multiple testing corrections with the FDR method, the P value was 0.168 under the dominant genetic model and the P-trend value was 0.054 for rs1342387. For variant rs266729 of ADIPOQ, which may influence the circulating adiponectin levels, there was no significant association with CRC risk under any genetic model (Table 2). None of the other SNPs (rs822395, rs2241766, and rs1501299 on ADIPOQ or rs12733285 on ADIPOR1) was significantly associated with CRC risk (Table 2).

Eligible studies for the meta-analysis

The working flow chart presented the selection process and the reasons for study exclusion from the meta-analysis studies (Figure 1). A total of 234 studies were initially retrieved by the database search, and 220 were excluded based on information in the titles and abstracts of the reports. For the 14 remaining, two studies that did not provide the detailed frequency data [19],[20] and another study reported by Yi et al. [21], with the same study population reported by Kaklamani et al. [9], were excluded. Thus, eleven case-control studies, along with our current study, were included in our meta-analysis (Additional file 1 Tables S2-S7) [9]-[13],[22]-[26].

Results of the meta-analysis studies

The four included reports, with five individual studies that recruited a total of 1,871 cases and 2,597 controls, have evaluated the association between variant rs1342387 and CRC risk (Additional file 1 Table S2) [9],[12],[13]. As determined by the meta-analysis, rs1342387 was found to be significantly associated with a reduced CRC risk, the pooled OR was 0.79 (95% CI = 0.66-0.95, P = 0.011; CT and TT vs. CC) under the random-effects model (Figure 2). Significant heterogeneity between the studies was found, as suggested by the I2 statistic and the Q-test (I2 = 50.4%; Q = 8.06, df = 4, P = 0.089; Table 3). The sensitivity analysis was performed by omitting one study at a time and recalculating the pooled ORs for the remained studies repeatedly. After excluding the study performed by He et al. [12], which contributed mostly to the heterogeneity between the studies, a consistent significant reduced risk for CRC was found with the pooled OR was 0.84 (95% CI = 0.73-0.98; I2 = 0%; Q = 2.51, df = 3, P = 0.47) for the CT and TT carriers in relative to CC carriers. No significant publication bias was found (Egger’s test, P = 0.209). Thus, the results suggested that rs1342387 may contribute to the susceptibility of CRC, which were consistent with the results of our population study.

rs266729 was firstly identified as a potential susceptibility locus on ADIPOQ for CRC (9). From the literature search, we identified six studies with seven subgroup studies that recruited a total of 3,635 cases and 4,411 controls (Additional file 1 Table S3) have evaluated the association between the rs266729 and colorectal cancer risk [9]-[13]. The meta-analysis showed that rs266729 did not associated with CRC risk (pooled OR = 0.93, 95% CI = 0.81-1.08, P = 0.354; CG/GG vs. CC) under the random effects model, and significant heterogeneity between the studies was found (I2 = 58.5%; Q = 14.45, df = 6, P = 0.025; Figure 3 and Table 3). After excluding the pioneer study conducted by Kaklamani et al. [9], which contributed mostly of the heterogeneity between the studies, the pooled OR was 1.00 (95% CI = 0.91-1.11; I2 = 0.7%; Q = 4.03, df = 4, P = 0.402) under the random-effects model. No significant publication bias was detected for the meta-analysis studies. The data indicated that rs266729 may be not a susceptibility factor for colorectal cancer.

The association of CRC risk and the other four loci were evaluated in six studies for rs2241766 (Additional file 1 Table S4), eight studies for rs1501299 (Additional file 1 Table S5), four studies for rs822395 (Additional file 1 Table S6), and three studies for rs12733285 (Additional file 1 Table S7). In our meta-analysis studies, we found no significant association between the loci and CRC risk (Table 3). The sensitivity analyses were performed to identify any individual study that significantly affects the overall estimates in the meta-analysis studies. Through sequential removal of individual study that has determined the association between the variant and CRC risk for rs822395 or rs12733285, the overall estimates for either locus did not significantly changed. However, when the study performed by Al-Harithy et al. [24] was excluded, which contributed mostly to the heterogeneity between the studies for rs2241766, the pooled OR was 1.26 (95% CI = 1.11-1.42; Q = 4.35, df = 5, P = 0.500, I2 = 0%) for the TG/GG carriers compared to TT carriers. For rs1501299, sensitivity analysis indicated that the study conducted by Tisilidiset al. [22] contributed mostly to the heterogeneity between the studies. The pooled OR was 0.89 (95% CI = 0.80-0.99; Q = 5.55, df = 8, p = 0.698; I2 = 0%) for TG/GG carriers compared to TT carriers after the study was excluded in the meta-analysis study. No significant publication bias was found, as determined by Egger’s test for all the meta-analysis studies (Table 3).

Discussion

From the hospital-based case-control study, we found that rs1342387 on ADIPOR1 was significantly associated with a reduced CRC risk; however, no significant association with the CRC risk for variants rs266729, rs2241766, rs822395, rs1501299, and rs12733285 was found. As determined by the meta-analysis of published epidemiological studies, only variant rs1342387 was significantly associated with the reduced CRC susceptibility, whereas limited data supported the associations between the other loci and CRC susceptibility. As the consistent results were found for the selected variants between hospital based case-control studies and the meta-analysis studies, which suggested that rs1342387 is associated with a reduced risk for colorectal cancer. Our results appeared to provide a genetic relationship between obesity, hyperinsulinemia, and/or insulin resistance and the risk of CRC.

Variant rs1342387 was associated with a reduced CRC risk in the Chinese population, which is consistent with the study conducted by He et al. [12] and the first-stage study of Kaklamani et al. [9]. Although the P value for multiple testing with the FDR method suggested a statistically non-significant association between the rs1342387 and CRC risk, which could be due to the high linkage disequilibrium (LD) between the variants, the results from the meta-analysis studies provided stronger evidence that the allele T carriers were associated with a significant reduced risk of CRC in relative to CC homozygotes. rs1342387 is located in intron 4 (+5843 C > T) of the ADIPOR1 gene, a locus associated with body size measurements, such as weight, height, waist and hip circumference, sagittal diameter, and body mass index [27]. Another study, performed in the Amish population, found that allele T for variant rs1342387 was associated with a reduced risk for type 2 diabetes, although the possibility that other functional loci in high linkage-disequilibrium with rs1342387 may account for this association could not be excluded [29]. Crimmins et al. summarized the association between the variants of ADIPOR1 and ADIPOR2 with insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes, and they found that only rs1342387 was significantly associated with the reduced risk for insulin resistance [30]. Since insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes may lead to susceptibility to various types of cancer, the variant may be a susceptibility factor for CRC and other obesity-related cancers.

The variant rs266729 has been reported to be associated with higher circulating adiponectin levels [31],[32], higher plasma total antioxidant status (32), lower plasma oxidized-LDL levels [33], and reduced risk for type 2 diabetes [34]. Other studies, however, did not find an association for the variant with blood lipids [35], blood pressure [35], or with coronary heart disease risk [36]. There are no significant allelic specific effects of promoter activity for rs266729 alone [37], and rs266729 may act together with other loci to regulate the activity of the adiponectin promoter [38]. In their first-stage study, Kaklamani et al. reported a significant association for the locus and CRC risk in a population of Ashkenazi origin. In their second-stage study, a significant association between the variant and CRC risk in a population of mixed origins was also noticed [9]. However, subsequent studies found no such association, except for one study conducted by He et al. have reported that the variant was associated with colon cancer susceptibility but not rectal cancer [12]. Meta-analysis of the epidemiological studies suggested that the locus does not contribute to CRC susceptibility. The original study may represent a chance observation. However, the possibility that the association observed by Kaklamani et al. [9] is attributed to the population-specific effects for rs266729 on CRC risk cannot be excluded, as the subsequent studies were conducted in other countries or races. There is also a possibility that the variant acts together with other variants to influence the CRC risk, and the genetic background may influence the association of the variant and CRC risk. Thus, more studies with fine-mapping methods, are warranted to address these questions.

For the other four variants, we found no significant association with CRC risk in our hospital based case-control population study, which was consistent with the results of the meta-analysis studies. For variant rs2241766, which is located on exon 2 of ADIPOQ, the G to T allelic change leads to a synonymous variation of the amino acid (Gly to Gly). The meta-analysis study found no significant association between the variant and CRC risk; however, the sensitivity study suggested that the results may be affected by the heterogeneity between the studies. rs1501299 is located on intron 2 (+276 G > T) of ADIPOQ and the meta-analysis conducted by Xu et al. found a decreased CRC risk for GT and TT carriers compared to GG carriers; however, only four studies were included [39]. For the current meta-analysis study, based on eight studies, suggested that the locus is not associated with CRC risk; however, when the study performed by Tisilidis et al. [22], which contributed mostly to the heterogeneity between the studies was excluded, the pooled estimate suggested that the variant may be a protective factor for CRC. Whether rs2241766 and rs1501299 are associated with the CRC susceptibility should be determined with more studies of relatively larger sample size. Variant rs822395 is located on intron 1 of ADIPOQ, and rs12733285 is located on intron 1 of ADIPOR1. Neither variant showed a significant association with CRC risk in our population study or in the meta-analysis studies.

We acknowledged that there were several limitations for the current study. Firstly, the investigation was a hospital based case-control study, which is more prone to selection bias of the participants. The age of the control subjects was slightly younger than that for the CRC cases, and the CRC risk for the controls was difficult to determine. Secondly, the relatively small sample size may lead to a lower statistical power to detect the association between rs266729 and other variants with CRC risk. Lastly, the underlying mechanisms for the association between rs1342387 and CRC risk need to be elucidated.

Conclusions

In conclusion, variant rs1342387 of ADIPOR1 may contribute to CRC susceptibility. Results from our population study and meta-analysis suggest that variants rs266729, rs822395, rs2241766, and rs1501299 of ADIPOQ and variant rs12733285 of ADIPOR1 may not contribute to CRC susceptibility. However, more investigations with larger sample sizes are warranted to validate these results and the underlying mechanisms are also need to be elucidated.

Additional file

References

Siddiqui AA: Metabolic syndrome and its association with colorectal cancer: a review. Am J Med Sci. 2011, 341: 227-231. 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181df9055.

Tsai CJ, Giovannucci EL: Hyperinsulinemia, Insulin Resistance, Vitamin D, and Colorectal Cancer Among Whites and African Americans. Dig Dis Sci. 2012, 57: 2497-503. 10.1007/s10620-012-2198-0.

Esteve E, Ricart W, Fernandez-Real JM: Adipocytokines and insulin resistance: the possible role of lipocalin-2, retinol binding protein-4, and adiponectin. Diabetes Care. 2009, 32 (Suppl 2): S362-367. 10.2337/dc09-S340.

Wei EK, Giovannucci E, Fuchs CS, Willett WC, Mantzoros CS: Low plasma adiponectin levels and risk of colorectal cancer in men: a prospective study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005, 97: 1688-1694. 10.1093/jnci/dji376.

Yoon MJ, Lee GY, Chung JJ, Ahn YH, Hong SH, Kim JB: Adiponectin increases fatty acid oxidation in skeletal muscle cells by sequential activation of AMP-activated protein kinase, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha. Diabetes. 2006, 55: 2562-2570. 10.2337/db05-1322.

Rasmussen MS, Lihn AS, Pedersen SB, Bruun JM, Rasmussen M, Richelsen B: Adiponectin receptors in human adipose tissue: effects of obesity, weight loss, and fat depots. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006, 14: 28-35. 10.1038/oby.2006.5.

Fujisawa T, Endo H, Tomimoto A, Sugiyama M, Takahashi H, Saito S, Inamori M, Nakajima N, Watanabe M, Kubota N, Yamauchi T, Kadowaki T, Wada K, Nakagama H, Nakajima A: Adiponectin suppresses colorectal carcinogenesis under the high-fat diet condition. Gut. 2008, 57: 1531-1538. 10.1136/gut.2008.159293.

Nishihara T, Baba M, Matsuda M, Inoue M, Nishizawa Y, Fukuhara A, Araki H, Kihara S, Funahashi T, Tamura S, Hayashi N, Iishi H, Shimomura I: Adiponectin deficiency enhances colorectal carcinogenesis and liver tumor formation induced by azoxymethane in mice. World J Gastroenterol. 2008, 14: 6473-6480. 10.3748/wjg.14.6473.

Kaklamani VG, Wisinski KB, Sadim M, Gulden C, Do A, Offit K, Baron JA, Ahsan H, Mantzoros C, Pasche B: Variants of the adiponectin (ADIPOQ) and adiponectin receptor 1 (ADIPOR1) genes and colorectal cancer risk. JAMA. 2008, 300: 1523-1531. 10.1001/jama.300.13.1523.

Pechlivanis S, Bermejo JL, Pardini B, Naccarati A, Vodickova L, Novotny J, Hemminki K, Vodicka P, Forsti A: Genetic variation in adipokine genes and risk of colorectal cancer. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009, 160: 933-940. 10.1530/EJE-09-0039.

Gornick MC, Rennert G, Moreno V, Gruber SB: Adiponectin gene and risk of colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2011, 105: 562-564. 10.1038/bjc.2011.259.

He B, Pan Y, Zhang Y, Bao Q, Chen L, Nie Z, Gu L, Xu Y, Wang S: Effects of genetic variations in the adiponectin pathway genes on the risk of colorectal cancer in the Chinese population. BMC Med Genet. 2011, 12: 94-10.1186/1471-2350-12-94.

Liu L, Zhong R, Wei S, Yin JY, Xiang H, Zou L, Chen W, Chen JG, Zheng XW, Huang LJ, Zhu BB, Chen Q, Duan SY, Rui R, Yang BF, Sun JW, Xie DS, Xu YH, Miao XP, Nie SF: Interactions between Genetic Variants in the Adiponectin, Adiponectin Receptor 1 and Environmental Factors on the Risk of Colorectal Cancer. PLoS One. 2011, 6: e27301-10.1371/journal.pone.0027301.

Li M, Zhou Y, Chen P, Yang H, Yuan X, Tajima K, Cao J, Wang H: Genetic variants on chromosome 8q24 and colorectal neoplasia risk: a case-control study in China and a meta-analysis of the published literature. PLoS One. 2011, 6: e18251-10.1371/journal.pone.0018251.

Wu X, Chen P, Ou Y, Liu J, Li C, Wang H, Qiang F: Association of variants on ADIPOQ and AdipoR1 and the prognosis of gastric cancer patients after gastrectomy treatment. Mol Biol Rep 2014, [Epub ahead of print].,

Loibl S, von Minckwitz G, Schwedler K, Schmidt KA, Hoper D, Kaufmann M, Costa SD: Mitomycin C, 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid (Mi-Fu-Fo) as salvage chemotherapy in breast cancer patients with liver metastases and impaired hepatic function: a phase II study. Anticancer Drugs. 2004, 15: 719-724. 10.1097/01.cad.0000136692.99971.ec.

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C: Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997, 315: 629-634. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629.

Yang H, Zhou Y, Zhou Z, Liu J, Yuan X, Matsuo K, Takezaki T, Tajima K, Cao J: A novel polymorphism rs1329149 of CYP2E1 and a known polymorphism rs671 of ALDH2 of alcohol metabolizing enzymes are associated with colorectal cancer in a southwestern Chinese population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009, 18: 2522-2527. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0398.

Carvajal-Carmona LG, Spain S, Kerr D, Houlston R, Cazier JB, Tomlinson I: Common variation at the adiponectin locus is not associated with colorectal cancer risk in the UK. Hum Mol Genet. 2009, 18: 1889-1892. 10.1093/hmg/ddp109.

Al Khaldi RM, Al Mulla F, Al Awadhi S, Kapila K, Mojiminiyi OA: Associations of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the adiponectin gene with adiponectin levels and cardio-metabolic risk factors in patients with cancer. Dis Markers. 2011, 30: 197-212. 10.1155/2011/832165.

Yi N, Kaklamani VG, Pasche B: Bayesian analysis of genetic interactions in case-control studies, with application to adiponectin genes and colorectal cancer risk. Ann Hum Genet. 2011, 75: 90-104. 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2010.00605.x.

Tsilidis KK, Helzlsouer KJ, Smith MW, Grinberg V, Hoffman-Bolton J, Clipp SL, Visvanathan K, Platz EA: Association of common polymorphisms in IL10, and in other genes related to inflammatory response and obesity with colorectal cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2009, 20: 1739-1751. 10.1007/s10552-009-9427-7.

Partida-Perez M, de la Luz A-MM, Peregrina-Sandoval J, Macias-Gomez N, Moreno-Ortiz J, Leal-Ugarte E, Cardenas-Meza M, Centeno-Flores M, Maciel-Gutierrez V, Cabrales E, Cervantes-Ortiz S, Gutiérrez-Angulo M: Association of LEP and ADIPOQ common variants with colorectal cancer in Mexican patients. Cancer Biomark. 2010, 7: 117-121.

Al-Harithy RN, Al-Zahrani MH: The adiponectin gene, ADIPOQ, and genetic susceptibility to colon cancer. Oncol Lett. 2012, 3: 176-180.

Keku TO, Vidal A, Oliver S, Hoyo C, Hall IJ, Omofoye O, McDoom M, Worley K, Galanko J, Sandler RS, Millikan R: Genetic variants in IGF-I, IGF-II, IGFBP-3, and adiponectin genes and colon cancer risk in African Americans and Whites. Cancer Causes Control. 2012, 23: 1127-38. 10.1007/s10552-012-9981-2.

Hu X, Yuan P, Yan J, Feng F, Li X, Liu W, Yang Y: Gene Polymorphisms of +45 T > G, -866G > A, and Ala54Thr on the Risk of Colorectal Cancer: A Matched Case-Control Study. PLoS One. 2013, 8: e67275-10.1371/journal.pone.0067275.

Qi L, Doria A, Giorgi E, Hu FB: Variations in adiponectin receptor genes and susceptibility to type 2 diabetes in women: a tagging-single nucleotide polymorphism haplotype analysis. Diabetes. 2007, 56: 1586-91. 10.2337/db06-1447.

Siitonen N, Pulkkinen L, Mager U, Lindstrom J, Eriksson JG, Valle TT, Hamalainen H, Ilanne-Parikka P, Keinanen-Kiukaanniemi S, Tuomilehto J, Laakso M, Uusitupa M: Association of sequence variations in the gene encoding adiponectin receptor 1 (ADIPOR1) with body size and insulin levels. The Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study. Diabetologia. 2006, 49: 1795-1805. 10.1007/s00125-006-0291-7.

Damcott CM, Ott SH, Pollin TI, Reinhart LJ, Wang J, O'Connell JR, Mitchell BD, Shuldiner AR: Genetic variation in adiponectin receptor 1 and adiponectin receptor 2 is associated with type 2 diabetes in the Old Order Amish. Diabetes. 2005, 54: 2245-2250. 10.2337/diabetes.54.7.2245.

Crimmins NA, Martin LJ: Polymorphisms in adiponectin receptor genes ADIPOR1 and ADIPOR2 and insulin resistance. Obes Rev. 2007, 8: 419-423. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00348.x.

Ong KL, Li M, Tso AW, Xu A, Cherny SS, Sham PC, Tse HF, Lam TH, Cheung BM, Lam KS: Association of genetic variants in the adiponectin gene with adiponectin level and hypertension in Hong Kong Chinese. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010, 163: 251-257. 10.1530/EJE-10-0251.

Persson J, Lindberg K, Gustafsson TP, Eriksson P, Paulsson-Berne G, Lundman P: Low plasma adiponectin concentration is associated with myocardial infarction in young individuals. J Intern Med. 2010, 268: 194-205. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02247.x.

Prior SL, Gable DR, Cooper JA, Bain SC, Hurel SJ, Humphries SE, Stephens JW: Association between the adiponectin promoter rs266729 gene variant and oxidative stress in patients with diabetes mellitus. Eur Heart J. 2009, 30: 1263-1269. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp090.

Han LY, Wu QH, Jiao ML, Hao YH, Liang LB, Gao LJ, Legge DG, Quan H, Zhao MM, Ning N, Kang Z, Sun H: Associations between single-nucleotide polymorphisms (+45 T > G, +276G > T, -11377C > G, -11391G > A) of adiponectin gene and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2011, 54 (9): 2303-2314. 10.1007/s00125-011-2202-9.

Zhao T, Zhao J: Genetic effects of adiponectin on blood lipids and blood pressure. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2011, 74: 214-222. 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2010.03902.x.

Pischon T, Pai JK, Manson JE, Hu FB, Rexrode KM, Hunter D, Rimm EB: Single nucleotide polymorphisms at the adiponectin locus and risk of coronary heart disease in men and women. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007, 15: 2051-2060. 10.1038/oby.2007.244.

Kyriakou T, Collins LJ, Spencer-Jones NJ, Malcolm C, Wang X, Snieder H, Swaminathan R, Burling KA, Hart DJ, Spector TD, O'Dell SD: Adiponectin gene ADIPOQ SNP associations with serum adiponectin in two female populations and effects of SNPs on promoter activity. J Hum Genet. 2008, 53: 718-727. 10.1007/s10038-008-0303-1.

Laumen H, Saningong AD, Heid IM, Hess J, Herder C, Claussnitzer M, Baumert J, Lamina C, Rathmann W, Sedlmeier EM, Klopp N, Thorand B, Wichmann HE, Illig T, Hauner H: Functional characterization of promoter variants of the adiponectin gene complemented by epidemiological data. Diabetes. 2009, 58: 984-991. 10.2337/db07-1646.

Xu Y, He B, Pan Y, Gu L, Nie Z, Chen L, Li R, Gao T, Wang S: The roles of ADIPOQ genetic variations in cancer risk: evidence from published studies. Mol Biol Rep. 2013, 40: 1135-1144. 10.1007/s11033-012-2154-2.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2012BAK01B00 and 2014AA020524), the National Nature Science Foundation (81125020, 81302507, 31200569 and 81302809), the Key Research Program(KSZD-EW-Z-021 and KSZD-EW-Z-019)of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (12431900500, 14391901800), and the Food Safety Research Center and Key Laboratory of Food Safety Research of INS, SIBS, CAS. And partially supported by General Programs (81273156,30771841 and 30700676) and a Major International (Regional) Joint Research Projects (30320140461) from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC), and by a Grant-in Aid for Scientific Research on Special Priority Areas of Cancer from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (12670383). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The author’s declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

PC, JC and HW conceived and designed the experiments; YO, ZZ and CL performed the experiments; YO, PC and JG analyzed the data; JL and KT contributed to the reagents, materials and related analysis tools; YO, PC and HW wrote the paper. All author’s read and approved the final manuscript.

Yiyi Ou, Peizhan Chen, Ziyuan Zhou contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

12881_2014_137_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Additional file 1: Table S1.: Information on primers and probes used for genotyping of the six variants. Table S2. Studies included in the meta-analysis for the association between rs1342387 and CRC. Table S3. Studies included in the meta-analysis for the association between rs266729 and CRC. Table S4. Studies included in the meta-analysis for the association between rs2241766 and CRC. Table S5. Studies included in the meta-analysis for the association between rs1501299 and CRC. Table S6. Studies included in the meta-analysis for the association between rs822395 and CRC. Table S7. Studies included in the meta-analysis for the association between rs12733285 and CRC. (DOCX 36 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Ou, Y., Chen, P., Zhou, Z. et al. Associations between variants on ADIPOQ and ADIPOR1 with colorectal cancer risk: a chinese case-control study and updated meta-analysis. BMC Med Genet 15, 137 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12881-014-0137-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12881-014-0137-y