Abstract

Background

The sustainable development goals aim to improve health for all by 2030. They incorporate ambitious goals regarding tuberculosis (TB), which may be a significant cause of disability, yet to be quantified. Therefore, we aimed to quantify the prevalence and types of TB-related disabilities.

Methods

We performed a systematic review of TB-related disabilities. The pooled prevalence of disabilities was calculated using the inverse variance heterogeneity model. The maps of the proportions of common types of disabilities by country income level were created.

Results

We included a total of 131 studies (217,475 patients) that were conducted in 49 countries. The most common type of disabilities were mental health disorders (23.1%), respiratory impairment (20.7%), musculoskeletal impairment (17.1%), hearing impairment (14.5%), visual impairment (9.8%), renal impairment (5.7%), and neurological impairment (1.6%). The prevalence of respiratory impairment (61.2%) and mental health disorders (42.0%) was highest in low-income countries while neurological impairment was highest in lower middle-income countries (25.6%). Drug-resistant TB was associated with respiratory (58.7%), neurological (37.2%), and hearing impairments (25.0%) and mental health disorders (26.0%), respectively.

Conclusions

TB-related disabilities were frequently reported. More uniform reporting tools for TB-related disability and further research to better quantify and mitigate it are urgently needed.

Prospero registration number

CRD42019147488

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Tuberculosis (TB) is a significant cause of death and disability worldwide, killing approximately 1.2 million people of an estimated 10 million new cases in 2019 [1]. While disability is a recognized consequence of TB, the prevalence of TB-related disability has not been estimated.

Disability includes any impairment or activity limitation as well as participation restriction [2]. Globally, low- and middle-income countries account for almost two-thirds of years lived with a disability [3]. While not well reported in the literature, TB can result in either temporary or permanent disability, arising from the disease process itself or side effects related to TB treatment, particularly related to second-line medicines used to treat drug-resistant (DR)-TB. TB service interruptions in high burden TB countries due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic may increase TB-related morbidity, disability, and mortality [4, 5].

Physical disabilities related to TB vary according to the bodily site affected by TB. For example, people with a history of pulmonary TB may suffer from a range of long-lasting respiratory-related sequelae such as impaired lung function (obstructive, restrictive, reduced diffusing capacity, or reduced lung volumes), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), bronchiectasis, aspergillosis, pulmonary hypertension, or pulmonary fibrosis [6,7,8,9]. The global burden of COPD as a consequence of TB has recently been estimated to be 5.9 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) [10]. TB of the nervous system, affecting the meninges, brain, spinal cord, or cranial and peripheral nerves, can cause severe irreversible disability [11]. For example, spinal TB can result in paraparesis and quadriparesis due to spinal deformity and damage of the neural structures, often leading to permanent physical disabilities [12]. Some disabilities arise due to organ or tissue destruction in the host from TB disease, while others are a result of adverse effects of treatment. TB treatment is effective, prevents death, and limits disability, but certain medications have side effects which may result in temporary or permanent disability. Previous studies have demonstrated an increased prevalence of visual disturbance and hearing loss among people previously treated for DR-TB [13, 14]. However, some of the medicines that were used in these studies such as kanamycin and capreomycin are no longer recommended by the World Health Organization [15].

Mental health disorders may also be more prevalent among TB survivors than the general population [16, 17]. Mood disorders including anxiety and depression may be associated with TB disease, TB treatment, or factors not directly related to TB. Whereas the long treatment duration of 9–20 months for DR-TB results in disruptions to usual work, family, and social activities, TB patients may also be subjected to stigma and discrimination due to cultural norms or beliefs associated with TB, which can cause or exacerbate mental health disorders. Although not well studied, the effect of TB treatment on the cognitive development of children and adolescents as a result of disruption to schooling may also be significant [18].

Despite a growing interest in the long-term sequelae associated with TB, the global prevalence of TB-related disability is currently unknown. Describing the spectrum and prevalence of TB-related disabilities is crucial to inform service provision and policy making in countries where TB is common and to mitigate future disability in patients being treated for TB. In this systematic review, we aimed to quantify the global prevalence and types of TB-related disabilities.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

We performed a systematic review following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [19]. We searched PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science databases for studies that reported on permanent disability associated with TB, using pre-specified search terms. We checked the reference lists of included papers for additional relevant references and performed a backwards and forwards citation search. Our search strategy (Additional file 1) was developed by a senior research information specialist (JC) and respiratory physician (AB), both with extensive experience in conducting systematic reviews in health and medicine.

The screening of articles by title and abstract was carried out independently by three researchers (KW, KAA and SC) in Rayyan [20]. Full-text papers were then independently screened by four researchers (KW, KAA, CK, and SC) using eligibility criteria described below. Disagreement was resolved through discussion and consensus.

Inclusion criteria

Participants were people in all age groups with any type of TB (pulmonary and extra pulmonary TB, new and relapse, drug-sensitive (DS), and DR-TB), from all regions and countries. Our intervention of interest was TB treatment based on national and international guidelines for TB (for both DS and DR-TB). However, studies without a specific intervention (i.e., for those who did not specifically report that the patients were on TB treatment but which clearly stated that the patients had been diagnosed with TB) were also included.

Our outcomes of interest were the prevalence of TB patients who developed a permanent form of disability, detected or reported after TB diagnosis, and where TB disease or TB treatment may have contributed to the disability. Our definitions of disability are included in Additional file 2.

We included observational studies (e.g., cross-sectional, case-control, or cohort studies) and experimental epidemiological studies that reported data from the year 2000 until July 2019. Our research question in the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome) format is included in Table 1.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded studies that reported temporary disabilities (for example, a mental health disorder attributable to an adverse event during treatment that was resolved by a change of medication). Descriptive epidemiological studies were also excluded (case reports and case series) as were other systematic reviews; scientific correspondence, posters, and conference abstracts; studies conducted in animals; and historical data reported before the year 2000.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data were extracted into a Microsoft Excel 2016 spreadsheet (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington, USA) by four researchers (KW, SC, CK, and KA). The data extraction spreadsheet was pilot tested and refined before extraction. The lists of variables included in the data extraction tool are available in the Additional file 3. All included articles were assessed for quality using a modified Ottawa Newcastle quality assessment scoring tool [21].

Data analysis

Meta-analysis was performed to estimate the pooled prevalence of each form of disability using the inverse variance heterogeneity model. Stratified analyses were conducted by country income-level and TB type, separately for each disability when two or more studies were available on the outcome of interest (see Additional file 4 for details).

This review was registered in the Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO, CRD42019147488). Ethical approval was not sought for this study as it includes an analysis of secondary data.

Results

Characteristics of the included studies

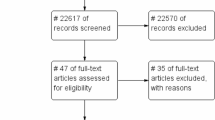

The search strategy yielded 3485 unique publications, 619 articles remained after the title and abstract screening. After full-text review, 124 publications (comprising 164 datasets) were included in the review. A backward and forward citation search found 410 publications, of which 53 were not identified in the original search; seven of these were subsequently included in the final analysis. Some studies reported more than one type of disability, and thus a total of 175 datasets (217,475 patients) from 131 unique studies were included (Fig. 1).

The characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 2. The included studies were conducted in 49 countries. The majority of studies were conducted in India 24.6% (n=43) followed by South Africa 9.7% (n=17) and Brazil 5.1% (n=9). The mean age of study participants was 36.7 years (±16.3) and 59.6% of cases were male. More than one-third of studies (39%, n=68) reported that their study population had DS-TB, while 29.1% (n=51) included patients with DR-TB. The site of TB disease was not reported in 41.1% of studies (n=72), while 28.6% (n=50) and 16.0% (n=28) included patients with pulmonary TB (PTB) and extra-pulmonary TB (EPTB), respectively. More than half of the studies (52.9%, n=90) reported that disabilities were diagnosed during TB treatment.

Prevalence of disabilities

The review showed that the most common type of disabilities were mental health disorders (23.1%), respiratory impairment (20.7%), musculoskeletal impairment (17.1%), hearing impairment (14.5%), visual impairment (9.8%), renal impairment (5.7%), and neurological impairment (1.6%).

Sources of heterogeneity

There was large heterogeneity in the prevalence of disability. Two variables, namely country income level and type of TB, were identified as the source of heterogeneity across all types of disability and therefore were used as the primary variables of stratification.

Prevalence of disabilities by country income level

Table 3 shows the number of studies and the prevalence of disabilities associated with TB, stratified by country income level. A total of 43 studies reported respiratory impairment. Nearly two-thirds of patients in LICs (61.2%) and just over half in LMICs (56.1%) experienced some form of respiratory impairment. The prevalence was low among HICs (14.9%) and UMICs (15.3%) (Fig. 2). Similarly, the highest prevalence of patients with mental health disorders was observed among patients in LICs (42%) followed by LMICs (31.3%), UMICs (30.6%), and HICs (4.3%; Fig. 3). The prevalence of patients with neurological function impairment was highest in LMICs (25.6%) and UMICs (15.9%) and lowest in LICs (5.9%) and HICs (1.3%; Fig. 4). The highest prevalence of TB patients who experienced hearing impairment (59.1%) was reported in HICs and UMICs 27.4% and 11.0% and 5% were reported from LMICs and LICs, respectively (Fig. 5).

Prevalence of disabilities by the type of TB

Among patients with DS-TB, the prevalence of respiratory impairment was 33.1% while 21.9% of patients reported mental disorders, 12.5% reported neurological impairment, 11.9% reported visual impairment, and 2.3% reported hearing impairment (Table 3). Among patients with DR-TB, the prevalence of patients reporting respiratory impairment was 58.7% while 26% reported mental disorder, 15% reported hearing impairment, 4.6% reported neurological impairment, and 2.7% reported visual impairment. Studies including patients with DS-TB and DR-TB (with the inclusion of an injectable agent) reported that 37.2% of patients had a neurological impairment, 33.1% had respiratory impairment, 25% had a hearing impairment, and 20.7% had a mental disorder, with none of the studies reporting visual impairment. Neurological impairment was also high in studies which included DS-TB and DR-TB patients who did not receive an injectable agent (28.5%). Additional information on disabilities by HIV status, timing of disability diagnosis, and study design is provided in Table 3.

Quality assessment

The quality of included studies was low to moderate overall, with a median score of 5 points (the maximum score is 9 points). Of the included 131 studies, only 11 studies had a score of 8 or 9 points, regarded as high-quality studies. The remaining studies scored 7 points or less, with 28 of them scoring 4 points or lower, classified as a low-quality study. Additional file 5: Table S1 presents the results of the quality assessment scores and Additional file 6: Table S2 includes the quality assessment tools.

Discussion

This systematic review attempts to quantify the prevalence and types of TB-related disabilities. We found a substantial burden of TB-related disabilities, with four common types: (1) respiratory impairment, (2) hearing impairment, (3) mental health disorders, and (4) neurological impairment.

Respiratory impairment

Respiratory impairment was the most common disability identified in this review. There was inconsistency in how respiratory impairment was diagnosed and reported. However, the prevalence of respiratory impairment was heterogeneous when stratified by country income level. The highest prevalence was reported in LICs (61.2%) and LMICs (56.1%). This may correlate with the high burden of TB in these countries, difficulties in accessing health care, or poverty. Poverty is widely recognized as a risk factor for TB and may also result in respiratory impairment [149,150,151]. High rates of respiratory impairment in LICs and LMICs may also be partially explained by low levels of health service coverage [152, 153]. High coverage of essential health services, including early access to TB diagnosis, treatment, and care, with appropriate monitoring of patients while on treatment, may minimize the long-term sequelae and disabilities associated with TB [154]. Other causes of lung diseases such as cigarette smoking and air pollution (indoor and outdoor) may contribute to the high prevalence of respiratory disabilities observed in LICs and LMICs [155, 156]. One systematic review reported a positive association between a history of TB treatment and chronic respiratory diseases, including COPD and bronchiectasis [157]. This association was much stronger in non-smokers and in high TB incidence countries [157]. WHO has recommended an integrated strategy to manage respiratory patients in primary health care settings with a focus on priority respiratory diseases, particularly TB [158].

Respiratory impairment was also higher among those with DR-TB. We found an almost twofold increase in the prevalence of respiratory impairment among patients with DR-TB (58.7%), compared with DS-TB (33.1%). This is consistent with previous research demonstrating a greater prevalence of COPD among successfully treated MDR-TB patients compared to patients treated for DS-TB and community controls [159]. This supports the notion of integration of DR-TB programs with respiratory health care. Importantly, there are currently no international guidelines that recommend screening for respiratory impairment after TB treatment, although there is interest in this from several clinical and public health groups [160]. Post TB treatment respiratory care including outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation may be beneficial for some TB survivors, especially in countries with a high burden of DR-TB. DR-TB treatment completion may be a possible entry point into these programs, where they exist. Similarly, national TB programs may want to consider how they provide incentives and enablers to patients with DR-TB so that they can monitor patients closely, or consider how they can link patients to services such as social protection schemes and disability services. Both are key interventions included in the End TB Strategy [161] and in many national TB strategic plans. While incentives and enablers are frequently provided, linkages to social protection and disability services are less frequently implemented.

Mental health disorders

Mental health disorders have historically been neglected as a focus in TB research [162,163,164]. Our review revealed a high prevalence of mental health disorders such as depression, anxiety and mood disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and psychosis among TB patients, with substantial variation by country income level. The highest prevalence of mental health disorders was reported in LICs (42%) and the lowest prevalence in HICs (4.3%). Although our study did not include comparison data for the general population, based on other literature, we note that the prevalence of mental health disorders among TB patients in our review is higher than the prevalence of mental health disorders among the general population [165]. The prevalence of mental health disorders in our review was similar to the prevalence of mental health disorders among people with other chronic diseases such as HIV infection [166], diabetes mellitus [167], and cancer [168], from previous systematic reviews.

The relationship between mental health disorders and TB may be specific to the socioeconomic context or other factors such as health care affordability. Also, it has been well documented that TB patients and their families frequently face stigma and discrimination [169, 170]. Depression, anxiety, and other mental health disorders could be connected to this experience of stigma, loss of identity, ongoing symptoms, and the socioeconomic consequences of TB [171]. Mental health disorders can contribute to an inability to complete TB treatment and subsequently to disability [172]. The high burden of mental health disorders associated with TB suggests that additional efforts are required to improve TB care [173, 174].

Hearing impairment

We found hearing impairment (hearing loss) among TB survivors to be common, particularly among patients with DR-TB or after taking second-line TB medications. The prevalence of hearing impairment among patients with DR-TB was 15%, which is seven times higher than the prevalence of hearing impairment among patients with DS-TB (2.3%). The disorder of hearing in patients on second-line TB medications, such as the aminoglycosides (i.e., amikacin, kanamycin, and streptomycin), is common [36, 175]. A previously published review of aminoglycoside-induced hearing impairment among TB patients also reported a high incidence of ototoxicity (7–90%) [176]. The appropriate use of TB medications should help health care providers prevent hearing loss among patients. Therefore, WHO now recommends MDR-TB treatment without the aminoglycosides [174].

We found that the prevalence of hearing impairment was higher in HICs (59%) and UMICs (27%) compared to LMICS (11%) and LICs (5%). This could be due to differences in diagnostic methods or the availability of diagnostic (auditory) equipment in HICs and UMICs to assess hearing impairment [22]. Ascertainment and/or publication bias may also be relevant here as few studies were available from LMICs and LICs. Different audiological assessment methods were used for the diagnosis of hearing impairment in our included studies, including otoscopy, pure tone audiometry, otoacoustic product emissions, and automated auditory brainstem response testing [22]. Audiometry was not always available for all patients to assess hearing impairment at baseline, during treatment, and after completion of TB treatment, to quantify the timeline of hearing loss. As a result, it was not possible to establish the main cause of hearing loss among patients with TB in this review. However the prevalence of hearing impairment in this review (14.6%) is substantially higher than the global estimates of people with disabling hearing loss in 2018 (6.1%) [177]. It is worthwhile to highlight the definition of hearing impairment as defined in this review and the local estimates may be different [174]. The hearing impairment could have a considerable effect on the quality of life, work, and social relationships [22, 178]. Therefore, hearing assessments for TB patients receiving aminoglycosides should be included as part of the management package. In addition, rehabilitation packages for those with hearing impairment should be offered routinely [22, 179].

Neurological impairment

The patients on the second-line injectable drugs reported more than 37% neurological impairment compared to patients without an injectable TB medication (28.5%). The most common types of TB-related neurological impairments reported in our review were paraplegia, hemiplegia, cranial nerve palsies, peripheral neuropathy, hydrocephalus, and visual loss. These neurological impairments were permanent and irreversible and therefore have long-term functional, social, economic, and psychological consequences for affected patients [180, 181]. TB of the central nervous system accounts for 5–10% of all EPTB globally, with TB meningitis, intracranial TB, and spinal TB being some of the most severe forms of TB [182, 183]. TB of the spine (or Pott’s disease) affects the intervertebral discs and adjacent vertebrae, which may result in vertebral collapse, destruction, skeletal deformities, and disability [184, 185]. In addition, compression of the spinal cord and/or nerves may result in neurologic deficits [186]. To reduce the burden of neurological deficits in children from TB meningitis, improving BCG vaccination coverage in countries with low coverage of BCG is an important intervention [187].

The findings of our review suggest a pressing need to prevent or screen for TB-related disability among TB patients and survivors. Strategies to prevent or reduce TB-related disability include improving access to health care, promoting early TB diagnosis, appropriate use of TB medications, and providing training for health care workers. Adverse event monitoring, pharmacovigilance, therapeutic drug monitoring, and providing incentives and enablers for patients for treatment adherence or compliance and report adverse events should be introduced as part of the TB treatment package. After TB treatment, care including follow-up and continued monitoring for possible disability or sequelae should be initiated urgently.

Limitations

This systematic review has several limitations. There was large heterogeneity in the prevalence of disabilities across studies which limited our ability to conduct a meta-analysis for all type of disabilities. There was also a large amount of missing data noted in our studies; for example, nearly 25% of studies had missing data for the type of TB, and HIV status was missing for 50% of the included studies. Therefore, we were unable to include these variables in the main analysis to explore the heterogeneity in these variables. In addition, in some studies, it was not possible to determine the temporal nature of the disability (i.e., whether disability occurred before, during, or after TB treatment) because the data were collected from studies that used cross-sectional study designs. For example, more than half of the papers (53%) included in the mental health impairment were cross-sectional studies. We may have some misclassification of disability for this reason. However, we attempted to explain this by conducting subgroup analysis. Moreover, we did not include studies published in languages other than English; 63 studies were excluded for this reason. Therefore, we may be missing important studies, from high TB and DR-TB burden countries such as China, the Russian Federation, and others. Lastly, as with all meta-analyses, the validity of the results is limited by the conduct and reporting of the studies from which the data were extracted and pooled.

Conclusions

TB-related disabilities are common affecting different body parts. The burden of TB-related disability varied by the income of country, susceptibility of TB, and second-line TB drugs. The commonly reported disabilities were respiratory impairment, hearing impairment, mental health disorders, and neurological impairment. Therefore, measures to prevent and reduce TB-related disabilities should be introduced urgently as a comprehensive TB treatment package.

Availability of data and materials

A list of included studies has been made available. The study protocol can be accessed on PROSPERO (CRD42019147488).

Abbreviations

- BCG:

-

Bacillus Calmette–Guerin

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease

- DALYs:

-

Disability-adjusted life years

- DR:

-

Drug-resistant

- DR-TB:

-

Drug-resistant TB

- DS:

-

Drug-sensitive

- EPTB:

-

Extra-pulmonary TB

- HICs:

-

High-income countries

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- LICs:

-

Low-income countries

- LMICs:

-

Low- and middle-income countries

- MDR-TB:

-

Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis

- PICO:

-

Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- PROSPERO:

-

Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews

- PTSD:

-

Post-traumatic stress disorder

- WPRO:

-

World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific

- TB:

-

Tuberculosis

- UMICs:

-

Upper middle-income countries

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

WHO. Global tuberculosis report 2020. Geneva; 2020.

WHO. International classification of functioning, disability and health. Geneva; 2012.

WHO. World Report of Disability. Geneva; 2011.

Alene KA, Wangdi K, Clements AC. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on tuberculosis control: an overview. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2020;5(3):123. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed5030123.

McQuaid CF, McCreesh N, Read JM, Sumner T, Houben RM, White RG, et al. The potential impact of COVID-19-related disruption on tuberculosis burden. Eur Respir J. 2020;56.

Byrne AL, Marais BJ, Mitnick CD, Garden FL, Lecca L, Contreras C, et al. Chronic airflow obstruction after successful treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. ERJ Open Research. 2017;3(3):00026–2017.

van Kampen SC, Wanner A, Edwards M, Harries AD, Kirenga BJ, Chakaya J, et al. International research and guidelines on post-tuberculosis chronic lung disorders: a systematic scoping review. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3(4):e000745. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000745.

Amaral AF, Coton S, Kato B, Tan WC, Studnicka M, Janson C, et al. Tuberculosis associates with both airflow obstruction and low lung function: BOLD results. Eur Respir J. 2015;46(4):1104–12. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.02325-2014.

Akkara S, Shah A, Adalja M, Akkara A, Rathi A, Shah D. Pulmonary tuberculosis: the day after. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17(6):810–3. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.12.0317.

Coates MM, Kintu A, Gupta N, Wroe EB, Adler AJ, Kwan GF, et al. Burden of non-communicable diseases from infectious causes in 2017: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(12).

Whiteman M, Espinoza L, Post MJ, Bell MD, Falcone S. Central nervous system tuberculosis in HIV-infected patients: clinical and radiographic findings. Am J Neuroradiol. 1995;16(6):1319–27.

Khanna K, Sabharwal S. Spinal tuberculosis: a comprehensive review for the modern spine surgeon. Spine J. 2019;19(11):1858–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2019.05.002.

Zhang J, Herdman T, Saunders M, Montoya R, Ramos E, Tovar M, et al. Rising burden of visual and auditory disability in patients after tuberculosis therapy in Peruvian slums. Int J Infect Dis. 2018;73(Suppl):348–9.

Gunasekeran DV, Gupta B, Cardoso J, Pavesio CE, Agrawal R. Visual morbidity and ocular complications in presumed intraocular tuberculosis: an analysis of 354 cases from a non-endemic population. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2018;26(6):865–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09273948.2017.1296580.

WHO. WHO consolidated guidelines on drug-resistant tuberculosis treatment. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019.

Van Rensburg AJ, Dube A, Curran R, Ambaw F, Murdoch J, Bachmann M, et al. Comorbidities between tuberculosis and common mental disorders: a scoping review of epidemiological patterns and person-centred care interventions from low-to-middle income and BRICS countries. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9(1):4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-019-0619-4.

Doherty AM, Kelly J, McDonald C, O’Dywer AM, Keane J, Cooney J. A review of the interplay between tuberculosis and mental health. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(4):398–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.03.018.

Franck C, Seddon JA, Hesseling AC, Schaaf HS, Skinner D, Reynolds L. Assessing the impact of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in children: an exploratory qualitative study. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14(1):426. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-14-426.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. System Rev. 2016;5(1):210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4.

Wells G, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale cohort studies. 2014.

Seddon JA, Godfrey-Faussett P, Jacobs K, Ebrahim A, Hesseling AC, Schaaf HS. Hearing loss in patients on treatment for drug-resistant tuberculosis. Eur Respir J. 2012;40(5):1277–86. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00044812.

Shean K, Streicher E, Pieterson E, Symons G, van Zyl SR, Theron G, et al. Drug-associated adverse events and their relationship with outcomes in patients receiving treatment for extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in South Africa. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e63057. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0063057.

Ghafari N, Rogers C, Petersen L, Singh SA. The occurrence of auditory dysfunction in children with TB receiving ototoxic medication at a TB hospital in South Africa. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;79(7):1101–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2015.04.040.

Sagwa EL, Ruswa N, Mavhunga F, Rennie T, Leufkens HG, Mantel-Teeuwisse AK. Comparing amikacin and kanamycin-induced hearing loss in multidrug-resistant tuberculosis treatment under programmatic conditions in a Namibian retrospective cohort. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;16(1):36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40360-015-0036-7.

Appana D, Joseph L, Paken J. An audiological profile of patients infected with multi-drug resistant tuberculosis at a district hospital in KwaZulu-Natal. S Afr J Commun Disord. 2016;63(1):e1–e12. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajcd.v63i1.154.

Khoza-Shangase K, Stirk M. Audiological testing for ototoxicity monitoring in adults with tuberculosis in state hospitals in Gauteng, South Africa. South Afr J Infect D. 2016;31(2):44–9.

Trebucq A, Schwoebel V, Kashongwe Z, Bakayoko A, Kuaban C, Noeske J, et al. Treatment outcome with a short multidrug-resistant tuberculosis regimen in nine African countries. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2018;22(1):17–25. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.17.0498.

Harouna SH, Ortuno-Gutierrez N, Souleymane MB, Kizito W, Morou S, Boukary I, et al. Short-course treatment outcomes and adverse events in adults and children-adolescents with MDR-TB in Niger. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2019;23(5):625–30. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.17.0871.

Cohen DB, Davies G, Malwafu W, Mangochi H, Joekes E, Greenwood S, et al. Poor outcomes in recurrent tuberculosis: more than just drug resistance? PLoS One. 2019;14(5):e0215855. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0215855.

Shibeshi W, Sheth AN, Admasu A, Berha AB, Negash Z, Yimer G. Nephrotoxicity and ototoxic symptoms of injectable second-line anti-tubercular drugs among patients treated for MDR-TB in Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2019;20(1):31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40360-019-0313-y.

Bloss E, Kuksa L, Holtz TH, Riekstina V, Skripconoka V, Kammerer S, et al. Adverse events related to multidrug-resistant tuberculosis treatment, Latvia, 2000-2004. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;14(3):275–81.

Ribeiro L, Sousa C, Sousa A, Ferreira C, Duarte R, Faria EAA, et al. Evaluation of hearing in patients with multiresistant tuberculosis. Acta Medica Port. 2015;28(1):87–91. https://doi.org/10.20344/amp.5783.

Batirel A, Erdem H, Sengoz G, Pehlivanoglu F, Ramosaco E, Gulsun S, et al. The course of spinal tuberculosis (Pott disease): results of the multinational, multicentre Backbone-2 study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21(11):1008 e9–e18.

Lima ML, Lessa F, Aguiar-Santos AM, Medeiros Z. Hearing impairment in patients with tuberculosis from Northeast Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2006;48(2):99–102. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0036-46652006000200008.

Vasconcelos KA, Frota S, Ruffino-Netto A, Kritski AL. The importance of audiometric monitoring in patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2017;50(5):646–51. https://doi.org/10.1590/0037-8682-0465-2016.

Kittikraisak W, Burapat C, Nateniyom S, Akksilp S, Mankatittham W, Sirinak C, et al. Improvements in physical and mental health among HIV-infected patients treated for TB in Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 39(6):1061-71.

Bhushan B, Chander R, Kajal N, Ranga V, Gupta A, Bharti H. Profile of adverse drug reactions in drug resistant tuberculosis from Punjab. Indian J Tuberc. 2014;61(4):318–24.

Nataprawira HM, Ruslianti V, Solek P, Hawani D, Milanti M, Anggraeni R, et al. Outcome of tuberculous meningitis in children: the first comprehensive retrospective cohort study in Indonesia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2016;20(7):909–14. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.15.0555.

Prasad K, Singh MB, Ryan H. Corticosteroids for managing tuberculous meningitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4:Cd002244.

Sharma V, Bhagat S, Verma B, Singh R, Singh S. Audiological evaluation of patients taking kanamycin for multidrug resistant tuberculosis. Iran J Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;28(86):203–8.

Synmon B, Kayal AK, Goswami M, Das M, Basumatary LJ. Spectrum of intra-cranial tuberculosis. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2015;18(6):S85.

Arockiaraj J, Karthik R, Michael JS, Amritanand R, David KS, Krishnan V, et al. ‘Need of the hour’: early diagnosis and management of multidrug resistant tuberculosis of the spine: an analysis of 30 patients from a “high multidrug resistant tuberculosis burden” country. Asian Spine J. 2019;13(2):265.

Piparva KG, Jansari G, Singh AP. Evaluation of treatment outcome and adverse drug reaction of directly observed treatment (DOT) plus regimen in multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) patients at district tuberculosis centre Rajkot. Perspect Clin Res. 2018;9(4):165–9.

Hoa NB, Nhung NV, Khanh PH, Hai NV, Quyen BT. Adverse events in the treatment of MDR-TB patients within and outside the NTP in Pham Ngoc Thach hospital, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8(1):809. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1806-4.

Ramma LD, Ibekwe TS. Efficacy of utilising patient self-report of auditory complaints to monitor aminoglycoside ototoxicity. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16(2):283. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.11.0712.

Singla N, Singla R, Fernandes S, Behera D. Post treatment sequelae of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis patients. Indian J Tuberc. 2009;56(4):206–12.

Aznar ML, Segura AR, Moreno MM, Espasa M, Sulleiro E, Bocanegra C, et al. Treatment outcomes and adverse events from a standardized multidrug-resistant tuberculosis regimen in a rural setting in Angola. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2019;101(3):502–9. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.19-0175.

Issa BA, Yussuf AD, Kuranga SI. Depression comorbidity among patients with tuberculosis in a university teaching hospital outpatient clinic in Nigeria. Ment Health Fam Med. 2009;6(3):133–8.

Deribew A, Hailemichael Y, Tesfaye M, Desalegn D, Wogi A, Daba S. The synergy between TB and HIV co-infection on perceived stigma in Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2010;3(1):249. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-3-249.

Ige OM, Lasebikan VO. Prevalence of depression in tuberculosis patients in comparison with non-tuberculosis family contacts visiting the DOTS clinic in a Nigerian tertiary care hospital and its correlation with disease pattern. Ment Health Fam Med. 2011;8(4):235–41.

van den Heuvel L, Chishinga N, Kiny AE, Weiss H, Patel V, et al. Frequency and correlates of anxiety and mood disorders among TB- and HIV-infected Zambians. AIDS Care. 2013;25(12):1527–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2013.793263.

Peltzer K, Naidoo P, Matseke G, Louw J, McHunu G, Tutshana B. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress symptoms and associated factors in tuberculosis (TB), TB retreatment and/or TB-HIV co-infected primary public health-care patients in three districts in South Africa. Psychol Health Med. 2013;18(4):387–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2012.726364.

Peltzer K, Louw J. Prevalence of suicidal behaviour & associated factors among tuberculosis patients in public primary care in South Africa. Indian J Med Res. 2013;138:194–200.

Xavier PB, Peixoto B. Emotional distress in Angolan patients with several types of tuberculosis. Afr Health Sci. 2015;15(2):378–84. https://doi.org/10.4314/ahs.v15i2.10.

Duko B, Gebeyehu A, Ayano G. Prevalence and correlates of depression and anxiety among patients with tuberculosis at WolaitaSodo University Hospital and Sodo Health Center, WolaitaSodo, South Ethiopia, Cross sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:214.

Kehbila J, Ekabe CJ, Aminde LN, Noubiap JJ, Fon PN, Monekosso GL. Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms in adult patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in the Southwest Region of Cameroon. Infect Dis Poverty. 2016;5(1):51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-016-0145-6.

Ambaw F, Mayston R, Hanlon C, Alem A. Burden and presentation of depression among newly diagnosed individuals with TB in primary care settings in Ethiopia. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1231-4.

Tomita A, Ramlall S, Naidu T, Mthembu SS, Padayatchi N, Burns JK. Major depression and household food insecurity among individuals with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) in South Africa. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2019;54(3):387–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01669-y.

Dasa TT, Roba AA, Weldegebreal F, Mesfin F, Asfaw A, Mitiku H, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of depression among tuberculosis patients in Eastern Ethiopia. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):82. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2042-6.

Aamir S, Aisha. Co-morbid anxiety and depression among pulmonary tuberculosis patients. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2010;20(10):703–4. https://doi.org/10.2010/JCPSP.703704.

Hadadi A, Rasoulinejad M, Khashayar P, Mosavi M, Maghighi MM. Osteoarticular tuberculosis in Tehran, Iran: a 2-year study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;16(8):1270–3. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03082.x.

Kaukab I, Nasir B, Abrar MA, Muneer S, Kanwal N, Shah SNH, et al. Effect of pharmacist-led patient education on management of depression in drug resistance tuberculosis patients using cycloserine. A prospective study. Lat Am J Pharm. 2015;34(7):1403–10.

Tariq A, Arshad S, Ejaz M. Frequency of depression in tuberculosis patients and its association with various sociodemographic factors. Pak J Med Health Sci. 2018;12(1):42–5.

Khan MQ, Wazir KU, Ali S, Fazil M. Prevalence of complications of tuberculous meningitis in patients presenting to paediatric department. Medical Forum Monthly. 2018;29(9):44–8.

Yilmaz A, Dedeli O. Assessment of anxiety, depression, loneliness and stigmatization in patients with tuberculosis. Acta Paul Enferm. 2016;29(5):549–57. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-0194201600076.

Soriano-Arandes A, Brugueras S, Rodriguez Chitiva A, Noguera-Julian A, Orcau A, Martin-Nalda A, et al. Clinical presentations and outcomes related to tuberculosis in children younger than 2 years of age in Catalonia. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:238. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2019.00238.

Dos Santos AP, Lazzari TK, Silva DR. Health-related quality of life, depression and anxiety in hospitalized patients with tuberculosis. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2017;80(1):69–76. https://doi.org/10.4046/trd.2017.80.1.69.

Castro-Silva KM, Carvalho AC, Cavalcanti MT, Martins PDS, Franca JR, Oquendo M, et al. Prevalence of depression among patients with presumptive pulmonary tuberculosis in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Braz J Psychiatry. 2019;41(4):316–23. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2018-0076.

Singh L, Pardal PK, Prakash J. Psychiatric morbidity in patients of pulmonary tuberculosis-an observational study. Ind Psychiatry J. 2015;24(2):168–71. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-6748.181722.

Galhenage JS, Rupasinghe JP, Abeywardena GS, de Silva AP, Williams SS, Gunasena B. Psychological morbidity and illness perception among patients receiving treatment for tuberculosis in a tertiary care centre in Sri Lanka. Ceylon Med J. 2016;61(1):37–40. https://doi.org/10.4038/cmj.v61i1.8261.

Akaputra R, Qurrotaa'yun S, Freisleben HJ. Effect of duration tuberculosis treatment on depression symptoms level of tuberculosis patients in Karang Bahagia. Prim Health Care Bekasi. 2017;2017:150–4.

Salodia UP, Sethi S, Khokhar A. Depression among tuberculosis patients attending a DOTS centre in a rural area of Delhi: a cross-sectional study. Indian J Public Health. 2019;63(1):39–43. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijph.IJPH_109_18.

Masumoto S, Yamamoto T, Ohkado A, Yoshimatsu S, Querri AG, Kamiya Y. Prevalence and associated factors of depressive state among pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Manila, The Philippines. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18(2):174–9. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.13.0335.

Shen X, Yuan Z, Mei J, Zhang Z, Guo J, Wu Z, et al. Anti-tuberculosis drug-induced liver injury in Shanghai: validation of Hy's Law. Drug Saf. 2014;37(1):43–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-013-0119-6.

Lee LY, Tung HH, Chen SC, Fu CH. Perceived stigma and depression in initially diagnosed pulmonary tuberculosis patients. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(23-24):4813–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13837.

Xu M, Markstrom U, Lyu J, Xu L. Survey on tuberculosis patients in rural areas in China: tracing the role of stigma in psychological distress. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(10).

Gong Y, Yan S, Qiu L, Zhang S, Lu Z, Tong Y, et al. Prevalence of depressive symptoms and related risk factors among patients with tuberculosis in China: a multistage cross-sectional study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;98(6):1624–8. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.17-0840.

Tinsa F, Essaddam L, Fitouri Z, Nouira F, Douira W, Ben Becher S, et al. Extra-pulmonary tuberculosis in children: a study of 41 cases. Tunis Med. 87(10):693–8.

Sezgi C, Taylan M, Kaya H, Sen HS, Abakay O, Bulut M, et al. Spinal tuberculosis: a retrospective chart review. Acta Medica Mediterr. 2014;30(3):725–30.

Samuel S, Boopalan PR, Alexander M, Ismavel R, Varghese VD, Mathai T. Tuberculosis of and around the ankle. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;50(4):466–72. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jfas.2011.04.002.

Kamara E, Mehta S, Brust JC, Jain AK. Effect of delayed diagnosis on severity of Pott's disease. Int Orthop. 2012;36(2):245–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-011-1432-2.

Agarwal A, Rastogi A. Tuberculosis of the elbow region in pediatric age group–experiences from a single centre. J Hand Surg Asian Pac Vol. 2017;22(04):457–63. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218810417500502.

Luo M, Wang W, Zeng Q, Luo Y, Yang H, Yang X. Tuberculous meningitis diagnosis and treatment in adults: a series of 189 suspected cases. Exp Ther Med. 2018;16(3):2770–6. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2018.6496.

Njoku CH, Makusidi MA, Ezunu EO. Experiences in management of Pott’s paraplegia and paraparesis in medical wards of Usmanu Danfodiyo University Teaching Hospital, Sokoto, Nigeria. Ann Afr Med. 2007;6(1):22–5. https://doi.org/10.4103/1596-3519.55735.

Benzagmout M, Boujraf S, Chakour K, Chaoui MF. Pott’s disease in children. Surg Neurol Int. 2011;2:1.

Shaikh MA, Shah M, Channa F. Criteria indicating morbidity in tuberculous meningitis. J Pak Med Assoc. 62(11):1137–9.

Nicolette N-B, Wilmshurst J, Muloiwa R, James N. Presentation and outcome of tuberculous meningitis among children: experiences from a tertiary children’s hospital. Afr Health Sci. 2014;14(1):143–9. https://doi.org/10.4314/ahs.v14i1.22.

Qureshi MA, Khalique AB, Afzal W, Pasha IF, Aebi M. Surgical management of contiguous multilevel thoracolumbar tuberculous spondylitis. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(S4):618–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-012-2459-9.

Eker A, Tansel O, Yuksel P, Celik AD. Evaluation of twelve patients with tuberculous meningitis. Turkiye Klinikleri Journal of Medical Sciences. 2008;28(6):909–15.

Christensen AS, Andersen AB, Thomsen VO, Andersen PH, Johansen IS. Tuberculous meningitis in Denmark: a review of 50 cases. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11(1):47. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-11-47.

Miftode EG, Dorneanu OS, Leca DA, Juganariu G, Teodor A, Hurmuzache M, et al. Tuberculous meningitis in children and adults: a 10-year retrospective comparative analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0133477. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0133477.

Paulsrud C, Poulsen A, Vissing N, Andersen PH, Johansen IS, Nygaard U. Think central nervous system tuberculosis, also in low-risk children: a Danish nationwide survey. Infect Dis. 2019;51(5):368–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/23744235.2019.1588471.

Lucena MM, da Silva FS, da Costa AD, Guimaraes GR, Ruas AC, Braga FP, et al. Evaluation of voice disorders in patients with active laryngeal tuberculosis. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0126876. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0126876.

De la Garza RR, Goodwin CR, Abu-Bonsrah N, Bydon A, Witham TF, Wolinsky J-P, et al. The epidemiology of spinal tuberculosis in the United States: an analysis of 2002–2011 data. J Neurosurg Spine. 2017;26(4):507–12.

Karande S, Gupta V, Kulkarni M, Joshi A. Prognostic clinical variables in childhood tuberculous meningitis: an experience from Mumbai, India. Neurol India. 2005;53(2):191–5; discussion 5-6. https://doi.org/10.4103/0028-3886.16407.

Kalita J, Misra UK, Ranjan P. Predictors of long-term neurological sequelae of tuberculous meningitis: a multivariate analysis. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14(1):33–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01534.x.

Wani AM, Hussain WM, Fatani M, Shakour BA, Akhtar M, Ibrahim F, et al. Clinical profile of tuberculous meningitis in kashmir valley-the Indian subcontinent. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2008;16(6):360–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/IPC.0b013e31817e5c16.

Garg RK, Sharma R, Kar AM, Kushwaha RA, Singh MK, Shukla R, et al. Neurological complications of miliary tuberculosis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2010;112(3):188–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2009.11.013.

Gunawardhana SA, Somaratne SC, Fernando MA, Gunaratne PS. Tuberculous meningitis in adults: a prospective study at a tertiary referral centre in Sri Lanka. Ceylon Med J. 2012;58(1):21–5.

Lisha PV, James PT, Ravindran C. Morbidity and mortality at five years after initiating Category I treatment among patients with new sputum smear positive pulmonary tuberculosis. Indian J Tuberc. 59(2):83–91.

Sheu JJ, Chiou HY, Kang JH, Chen YH, Lin HC. Tuberculosis and the risk of ischemic stroke: a 3-year follow-up study. Stroke. 2010;41(2):244–9. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.567735.

Chen CH, Chang YJ, Sy HN, Chen WL, Yen HC. Risk assessment of the outcome for cerebral infarction in tuberculous meningitis. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2014;170(8-9):512–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurol.2014.06.004.

Chen H-L, Lu C-H, Chang C-D, Chen P-C, Chen M-H, Hsu N-W, et al. Structural deficits and cognitive impairment in tuberculous meningitis. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15(1):1–9.

Shen CH, Chou CH, Liu FC, Lin TY, Huang WY, Wang YC, et al. Association between tuberculosis and Parkinson disease: a nationwide, population-based cohort study. Medicine. 2016;95(8):e2883. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000002883.

Manji M, Shayo G, Mamuya S, Mpembeni R, Jusabani A, Mugusi F. Lung functions among patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in Dar es Salaam - a cross-sectional study. BMC Pulm Med. 2016;16(1):58. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-016-0213-5.

Arnold A, Cooke GS, Kon OM, Dedicoat M, Lipman M, Loyse A, et al. Adverse effects and choice between the injectable agents amikacin and capreomycin in multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61(9).

Wagaskar VG, Chirmade RA, Baheti VH, Tanwar HV, Patwardhan SK, Gopalakrishnan G. Urinary tuberculosis with renal failure: challenges in management. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(1):PC01–3. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2016/16409.7017.

Maydell A, Goussard P, Andronikou S, Bezuidenhout F, Ackermann C, Gie R. Radiological changes post-lymph node enucleation for airway obstruction in children with pulmonary tuberculosis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;38(4):478–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.02.008.

Mbatchou Ngahane BH, Nouyep J, Nganda Motto M, Mapoure Njankouo Y, Wandji A, Endale M, et al. Post-tuberculous lung function impairment in a tuberculosis reference clinic in Cameroon. Respir Med. 2016;114:67–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2016.03.007.

Chin AT, Rylance J, Makumbirofa S, Meffert S, Vu T, Clayton J, et al. Chronic lung disease in adult recurrent tuberculosis survivors in Zimbabwe: a cohort study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 23(2):203–11.

Fiogbe AA, Agodokpessi G, Tessier JF, Affolabi D, Zannou DM, Ade G, et al. Prevalence of lung function impairment in cured pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Cotonou, Benin. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2019;23(2):195–202. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.18.0234.

Mkoko P, Naidoo S, Mbanga LC, Nomvete F, Muloiwa R, Dlamini S. Chronic lung disease and a history of tuberculosis (post-tuberculosis lung disease): Clinical features and in-hospital outcomes in a resource-limited setting with a high HIV burden. S Afr Med J. 2019;109(3):169–73. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2019.v109i3.13366.

Baig IM, Saeed W, Khalil KF. Post-tuberculous chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2010;20(8):542–4.

Radovic M, Ristic L, Ciric Z, Dinic-Radovic V, Stankovic I, Pejcic T, et al. Changes in respiratory function impairment following the treatment of severe pulmonary tuberculosis - limitations for the underlying COPD detection. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:1307–16. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S106875.

Vashakidze SA, Kempker JA, Jakobia NA, Gogishvili SG, Nikolaishvili KA, Goginashvili LM, et al. Pulmonary function and respiratory health after successful treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis. Int J Infect Dis. 2019;82:66–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2019.02.039.

Ramos LM, Sulmonett N, Ferreira CS, Henriques JF, de Miranda SS. Functional profile of patients with tuberculosis sequelae in a university hospital. J Bras Pneumol. 2006;32(1):43–7. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37132006000100010.

Morrone N, Abe NS. Bronchoscopic findings in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. J Bronchol. 2007;14(1):15–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/LBR.0b013e31802c2fcb.

Byrne AL, Marais BJ, Mitnick CD, Garden FL, Lecca L, Contreras C, et al. Chronic airflow obstruction after successful treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. ERJ Open Res. 2017;3(3).

Godoy MDP, Mello FCQ, Lopes AJ, Costa W, Guimaraes FS, Pacheco AGF, et al. The functional assessment of patients with pulmonary multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Respir Care. 2012;57(11):1949–54. https://doi.org/10.4187/respcare.01532.

Nihues SDE, Mancuzo EV, Sulmonetti N, Sacchi FPC, Viana VD, Netto EM, et al. Chronic symptoms and pulmonary dysfunction in post-tuberculosis Brazilian patients. Braz J Infect Dis. 2015;19(5):492–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjid.2015.06.005.

Maguire GP, Anstey NM, Ardian M, Waramori G, Tjitra E, Kenangalem E, et al. Pulmonary tuberculosis, impaired lung function, disability and quality of life in a high-burden setting. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009;13(12):1500–6.

Bhattacharyya SK, Mandal A, Thakur SB, Mukherjee S, Saha SK, Ghoshal AG. Radiological evaluation of chest in abdominal tuberculosis. J Clin Diagn Res. 2011;5(5):926–8.

Das M, Isaakidis P, Van den Bergh R, Kumar AM, Nagaraja SB, Valikayath A, et al. HIV, multidrug-resistant TB and depressive symptoms: when three conditions collide. Glob Health Action. 2014;7(1):24912. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v7.24912.

Gandhi K, Gupta S, Singla R. Risk factors associated with development of pulmonary impairment after tuberculosis. Indian J Tuberc. 2016;63(1):34–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijtb.2016.01.006.

Panda A, Bhalla AS, Sharma R, Mohan A, Sreenivas V, Kalaimannan U, et al. Correlation of chest computed tomography findings with dyspnea and lung functions in post-tubercular sequelae. Lung India. 2016;33(6):592–9. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-2113.192871.

Aggarwal D, Gupta A, Janmeja A, Bhardwaj M. Evaluation of tuberculosis-associated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at a tertiary care hospital: a case–control study. Lung India. 2017;34(5):415–9. https://doi.org/10.4103/lungindia.lungindia_522_16.

Mukati S, Julka A, Varudkar HG, Singapurwala M, Agrawat JC, Bhari D, et al. A study of clinical profile of cases of MDR-TB and evaluation of challenges faced in initiation of second line Anti tuberculosis treatment for MDR-TB cases admitted in drug resistance tuberculosis center. Indian J Tuberc. 2016;66(3).

Santra A, Dutta P, Manjhi R, Pothal S. Clinico-radiologic and spirometric profile of an Indian population with post-tuberculous obstructive airway disease. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(3):Oc35–oc8.

Patil S, Patil R, Jadhav A. Pulmonary functions’ assessment in post-tuberculosis cases by spirometry: obstructive pattern is predominant and needs cautious evaluation in all treated cases irrespective of symptoms. Int J Mycobacteriol. 2018;7(2):128–33. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijmy.ijmy_56_18.

Singla R, Mallick M, Mrigpuri P, Singla N, Gupta A. Sequelae of pulmonary multidrug-resistant tuberculosis at the completion of treatment. Lung India. 2018;35(1):4–8. https://doi.org/10.4103/lungindia.lungindia_269_16.

Gupte AN, Paradkar M, Selvaraju S, Thiruvengadam K, Shivakumar S, Sekar K, et al. Assessment of lung function in successfully treated tuberculosis reveals high burden of ventilatory defects and COPD. PLoS One. 2019;14(5):e0217289. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0217289.

Lee JH, Chang JH. Lung function in patients with chronic airflow obstruction due to tuberculous destroyed lung. Respir Med. 2003;97(11):1237–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0954-6111(03)00255-5.

Lam KBH, Jiang CQ, Jordan RE, Miller MR, Zhang WS, Cheng KK, et al. Prior TB, smoking, and airflow obstruction a cross-sectional analysis of the Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study. Chest. 2010;137(3):593–600. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.09-1435.

Hwang YI, Kim JH, Lee CY, Park S, Park YB, Jang SH, et al. The association between airflow obstruction and radiologic change by tuberculosis. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6(5):471–6. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.04.02.

Rhee CK, Yoo KH, Lee JH, Park MJ, Kim WJ, Park YB, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with tuberculosis-destroyed lung. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17(1):67–75. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.12.0351.

Jung JW, Choi JC, Shin JW, Kim JY, Choi BW, Park IW. Pulmonary impairment in tuberculosis survivors: The Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2008-2012. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0141230. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0141230.

Jo YS, Park JH, Lee JK, Heo EY, Chung HS, Kim DK. Risk factors for pulmonary arterial hypertension in patients with tuberculosis-destroyed lungs and their clinical characteristics compared with patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:2433–43. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S136304.

Jin J, Li S, Yu W, Liu X, Sun Y. Emphysema and bronchiectasis in COPD patients with previous pulmonary tuberculosis: computed tomography features and clinical implications. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:375–84. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S152447.

Park HJ, Byun MK, Kim HJ, Ahn CM, Kim DK, Kim YI, et al. History of pulmonary tuberculosis affects the severity and clinical outcomes of COPD. Respirology. 2018;23(1):100–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/resp.13147.

Sun F, Li L, Liao X, Yan X, Han R, Lei W, et al. Adjunctive use of prednisolone in the treatment of free-flowing tuberculous pleural effusion: A retrospective cohort study. Respir Med. 2018;139:86–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2018.05.002.

Akkara SA, Shah AD, Adalja M, Akkara AG, Rathi A, Shah DN. Pulmonary tuberculosis: the day after. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17(6):810–3. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.12.0317.

Urzua CA, Lantigua Y, Abuauad S, Liberman P, Berger O, Sabat P, et al. Clinical features and prognostic factors in presumed ocular tuberculosis. Curr Eye Res. 2017;42(7):1029–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/02713683.2016.1266663.

Gunasekeran DV, Agrawal RV, Grant R, Pavesio C, Gupta V. The collaborative ocular tuberculosis study (cots), an international study of the clinical evaluation and management of ocular tuberculosis at 25 centres: Report 1 on clinical assessment and management outcomes. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2016;45(9):S227.

Basu S, Monira S, Modi RR, Choudhury N, Mohan N, Padhi TR, et al. Degree, duration, and causes of visual impairment in eyes affected with ocular tuberculosis. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2014;4(1):1–5.

Hsia NY, Ho YH, Shen TC, Lin CL, Huang KY, Chen CH, et al. Risk of cataract for people with tuberculosis: Results from a population-based cohort study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2015;19(3):305–11. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.14.0380.

Satti H, Mafukidze A, Jooste PL, McLaughlin MM, Farmer PE, Seung KJ. High rate of hypothyroidism among patients treated for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Lesotho. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16(4):468–72. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.11.0615.

Prakash J, Mehtani A. Hand and wrist tuberculosis in paediatric patients - our experience in 44 patients. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2017;26(3):250–60. https://doi.org/10.1097/BPB.0000000000000325.

Lancet T. Tackling poverty in tuberculosis control: Elsevier; 2005.

Spence DP, Hotchkiss J, Williams CS, Davies PD. Tuberculosis and poverty. Bmj. 1993;307(6907):759–61. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.307.6907.759.

Oxlade O, Murray M. Tuberculosis and poverty: why are the poor at greater risk in India? PLoS One. 2012;7(11).

WHO WB. Tracking Universal Health Coverage: 2017 Global Monitoring Report: World Health Organization and International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank; 2017.

Wagstaff A, Neelsen S. A comprehensive assessment of universal health coverage in 111 countries: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;8:39–49.

Lee C-H, Lee M-C, Lin H-H, Shu C-C, Wang J-Y, Lee L-N, et al. Pulmonary tuberculosis and delay in anti-tuberculous treatment are important risk factors for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e37978. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0037978.

Cohen AJ, Brauer M, Burnett R, Anderson HR, Frostad J, Estep K, et al. Estimates and 25-year trends of the global burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution: an analysis of data from the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2015. Lancet. 2017;389(10082):1907–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30505-6.

Öberg M, Jaakkola MS, Woodward A, Peruga A, Prüss-Ustün A. Worldwide burden of disease from exposure to second-hand smoke: a retrospective analysis of data from 192 countries. Lancet. 2011;377(9760):139–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61388-8.

Byrne AL, Marais BJ, Mitnick CD, Lecca L, Marks GB. Tuberculosis and chronic respiratory disease: a systematic review. Int J Infect Dis. 2015;32:138–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2014.12.016.

WHO. Practical approach to lung health (PAL): A primary health care strategy for the integrated management of respiratory conditions in people five years of age and over: World Health Organization; 2005.

Byrne AL, Marais BJ, Mitnick CD, Garden FL, Lecca L, Contreras C, et al. Chronic airflow obstruction after successful treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. ERJ Open Research. 2017;3(3).

Allwood B, van der Zalm M, Amaral A, Byrne A, Datta S, Egere U, et al. Post-tuberculosis lung health: perspectives from the First International Symposium. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2020;24(8):820–8. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.20.0067.

Organization WH. Implementing the end TB strategy: the essentials: World Health Organization; 2015. Report No.: 9241509937

Sweetland AC, Jaramillo E, Wainberg ML, Chowdhary N, Oquendo MA, Medina-Marino MA, et al. Tuberculosis: an opportunity to integrate mental health services in primary care in low-resource settings. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(12):952–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30347-X.

Mason PH, Sweetland AC, Fox GJ, Halovic S, Nguyen TH, Marks GB. Tuberculosis and mental health in the Asia-Pacific. Australas Psychiatry. 2016;24(6):553–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856216649770.

Sweetland AC, Galea J, Shin S, Driver C, Dlodlo R, Karpati A, et al. Integrating tuberculosis and mental health services: global receptivity of national tuberculosis program directors. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2019;23(5):600–5.

Steel Z, Marnane C, Iranpour C, Chey T, Jackson JW, Patel V, et al. The global prevalence of common mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis 1980–2013. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(2):476–93. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyu038.

Grigsby AB, Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. Prevalence of anxiety in adults with diabetes: a systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53(6):1053–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00417-8.

Roy T, Lloyd CE. Epidemiology of depression and diabetes: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2012;142:S8–S21. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0327(12)70004-6.

Maass SW, Roorda C, Berendsen AJ, Verhaak PF, de Bock GH. The prevalence of long-term symptoms of depression and anxiety after breast cancer treatment: a systematic review. Maturitas. 2015;82(1):100–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.04.010.

Craig G, Daftary A, Engel N, O’driscoll S, Ioannaki A. Tuberculosis stigma as a social determinant of health: a systematic mapping review of research in low incidence countries. Int J Infect Dis. 2017;56:90–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2016.10.011.

Lönnroth K, Castro KG, Chakaya JM, Chauhan LS, Floyd K, Glaziou P, et al. Tuberculosis control and elimination 2010–50: cure, care, and social development. Lancet. 2010;375(9728):1814–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60483-7.

Thoits PA. Self, identity, stress, and mental health. Handbook of the sociology of mental health: Springer; 2013. p. 357–77.

Pachi A, Bratis D, Moussas G, Tselebis A. Psychiatric morbidity and other factors affecting treatment adherence in pulmonary tuberculosis patients. Tuberc Res Treat. 2013;2013:1–37. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/489865.

WHO. Companion handbook to the WHO guidelines for the programmatic management of drug-resistant tuberculosis: World Health Organization; 2014.

WHO Consolidated Guidelines on Tuberculosis. Module 4: Treatment - Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis Treatment: WHO; 2020.

Lima ML, Lessa F, Aguiar-Santos AM, Medeiros Z. Hearing impairment in patients with tuberculosis from Northeast Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 48(2):99–102.

Petersen L, Rogers C. Aminoglycoside-induced hearing deficits–a review of cochlear ototoxicity. S Afr Fam Pract. 2015;57(2):77–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/20786190.2014.1002220.

WHO. World report on hearing. Geneva; 2021.

Cox H, Reuter A, Furin J, Seddon J. Prevention of hearing loss in patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Lancet. 2017;390(10098):934. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32170-0.

Byaruhanga R, Roland JT Jr, Buname G, Kakande E, Awubwa M, Ndorelire C, et al. A case report: the first successful cochlear implant in Uganda. Afr Health Sci. 2015;15(4):1342–8. https://doi.org/10.4314/ahs.v15i4.38.

Mafukidze AT, Calnan M, Furin J. Peripheral neuropathy in persons with tuberculosis. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2016;2:5–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jctube.2015.11.002.

Maguire G, Anstey NM, Ardian M, Waramori G, Tjitra E, Kenangalem E, et al. Pulmonary tuberculosis, impaired lung function, disability and quality of life in a high-burden setting. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009;13(12):1500–6.

Caminero J, Van Deun A, Fujiwara P. Guidelines for clinical and operational management of drug-resistant tuberculosis. Paris: International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease; 2013. p. 18–9.

Thakur K, Das M, Dooley KE, Gupta A, editors. The global neurological burden of tuberculosis, Seminars in neurology: Thieme Medical Publishers; 2018.

Garg RK, Somvanshi DS. Spinal tuberculosis: a review. J Spinal Cord Med. 2011;34(5):440–54. https://doi.org/10.1179/2045772311Y.0000000023.

Garg RK, Malhotra HS, Gupta R. Spinal cord involvement in tuberculous meningitis. Spinal Cord. 2011;53(9):649–57.

Garg R, Somvanshi D. Spinal tuberculosis: a review. J Spinal Cord Med. 2011;34(5):440–54. https://doi.org/10.1179/2045772311Y.0000000023.

Syggelou A, Spyridis N, Benetatou K, Kourkouni E, Kourlaba G, Tsagaraki M, et al. BCG vaccine protection against TB infection among children older than 5 years in close contact with an infectious adult TB case. J Clin Med. 2020;9(3224).

Acknowledgements

Thank you for ANU and WHO WPRO for providing the opportunity to undertake this collaborative project.

Funding

This review was funded by the End TB Unit, World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific, under an Agreement for Performance of Work contract, with Australian National University. In-kind support was provided by the Australian National University, Curtin University, the Telethon Kids Institute, The University of Sydney, and Bond University. KV is supported by a Sidney Sax Early Career Fellowship from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), Canberra ACT, Australia (GNT1121611). SC is supported by NHMRC ISER Centre for Research Excellence grant (APP1107393). KAA is funded by NHMRC Investigator Grant (APP1196549). The funders provided no input into the undertaking or reporting of the research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KAA, KW, and KV conceived the study, which was refined by SC, KC, TI, KR, FM, AB, and JC. JC conducted the literature search. KAA, KW, SC, and KC screened the full-text papers and extracted the data. KAA run the analysis. KAA, KW, SC, KC, and KV drafted the manuscript, and all authors provided input into revisions and approved the final draft for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Search strategies.

Additional file 2.

Definitions of disability in our study.

Additional file 3.

Variables included in the data extraction tools.

Additional file 4.

Data analysis.

Additional file 5: Table S1.

Quality assessment tools.

Additional file 6: Table S2.

Quality assessment article summary table.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Alene, K.A., Wangdi, K., Colquhoun, S. et al. Tuberculosis related disability: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med 19, 203 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-021-02063-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-021-02063-9