Abstract

Background

Early provision of palliative care, at least 3–4 months before death, can improve patient quality of life and reduce burdensome treatments and financial costs. However, there is wide variation in the duration of palliative care received before death reported across the research literature. This study aims to determine the duration of time from initiation of palliative care to death for adults receiving palliative care across the international literature.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis that was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42018094718). Six databases were searched for articles published between Jan 1, 2013, and Dec 31, 2018: MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, Global Health, Web of Science and The Cochrane Library, as well undertaking citation list searches. Following PRISMA guidelines, articles were screened using inclusion (any study design reporting duration from initiation to death in adults palliative care services) and exclusion (paediatric/non-English language studies, trials influencing the timing of palliative care) criteria. Quality appraisal was completed using Hawker’s criteria and the main outcome was the duration of palliative care (median/mean days from initiation to death).

Results

One hundred sixty-nine studies from 23 countries were included, involving 11,996,479 patients. Prior to death, the median duration from initiation of palliative care to death was 18.9 days (IQR 0.1), weighted by the number of participants. Significant differences between duration were found by disease type (15 days for cancer vs 6 days for non-cancer conditions), service type (19 days for specialist palliative care unit, 20 days for community/home care, and 6 days for general hospital ward) and development index of countries (18.91 days for very high development vs 34 days for all other levels of development). Forty-three per cent of studies were rated as ‘good’ quality. Limitations include a preponderance of data from high-income countries, with unclear implications for low- and middle-income countries.

Conclusions

Duration of palliative care is much shorter than the 3–4 months of input by a multidisciplinary team necessary in order for the full benefits of palliative care to be realised. Furthermore, the findings highlight inequity in access across patient, service and country characteristics. We welcome more consistent terminology and methodology in the assessment of duration of palliative care from all countries, alongside increased reporting from less-developed settings, to inform benchmarking, service evaluation and quality improvement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Palliative care aims to improve the quality of life of patients with life-limiting illnesses through prevention and relief of suffering [1]. Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses demonstrate that early integration of specialist palliative care can improve quality of life for patients with advanced, incurable illness, including reducing symptom intensity, hospitalisation, aggressive treatments and associated costs at the end of life [2,3,4]. Studies included patients with malignant and non-malignant disease. Definitions of early integration vary. Although there is a paucity of well-conducted randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with mixed findings across trials, evidence suggests that ‘for full benefits of palliative care to be realized, continuity by a multidisciplinary team is needed for at least 3–4 months’ [5] to realise maximum benefit.

The 2018 Lancet Commission on Palliative Care and Pain Relief identified a lack of palliative care and pain relief globally [6]. By 2060, the burden of serious health-related suffering is expected to increase almost twofold, most rapidly in low-income countries [7]. Studies reporting on the duration of palliative care vary (e.g. from a median of 18–57 days and mean of 30–70 days), and suggest that early integration is not routine practice [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19].

To date, there have been no attempts to systematically summarise reports on the duration of palliative care across the research literature. Doing so with a global focus could allow local and national services to benchmark using an international standard, determine country variations reflecting differences in wealth and palliative care development, and would identify the gap between current routine practice and the ideal duration of 3–4 months of palliative care.

This systematic review aims to identify studies reporting on the time interval between initiation of specialised palliative care services and death for adult patients within routine clinical practice and to explore associated patient, service and country characteristics which influence this duration.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis. The study protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42018094718) on 30 April 2018. Ethics approval was not required for this secondary data analysis.

Data sources and searches

Databases searched included MEDLINE (1946 to January 2019), Embase (1947 to January 2019), CINAHL (1960 to January 2019), Global Health (1973 to January 2019), Web of Science (1990 to January 2019) and The Cochrane Library. We conducted database searches on 2 October 2017 with additional updates on 12 February 2018 and 15 January 2019. The search strategy included terms for palliative care, duration of palliative care and referral (see example MEDLINE strategy provided in Additional file 1: Fig S1). Additional studies were identified through hand-searching of reference and citation lists of included studies. Search strategies (e.g. Additional file 1: Fig S1) were used to conduct a scoping search in October 2020 to determine whether any eligible population-based or large-scale studies had been published since January 2019. Of the 667 abstracts identified, no eligible population-based or large studies were identified so an updated extraction and analysis including data from 2019 was not undertaken.

Study selection

Studies were included if they reported on adult patients (≥ 18 years old) referred to or admitted under adult palliative care services. Palliative care services were defined as healthcare services which either self-define as specialist palliative care services or solely or majorly practise palliative care. These services could be in any setting including general hospital wards, specialist inpatient units/hospices or community settings (outpatients/day units/home care). Studies were only included if they reported length-of-stay in a specialist inpatient palliative care unit, referral-to-death time interval in any setting or survival time after palliative care referral. We limited search results to studies published from 1 January 2013 to 31 December 2018 to reflect contemporary practice. Included studies could be of any study design. Unpublished study data were included after contact with study investigators. Studies were excluded if they included children (< 18 years old) or referrals to paediatric palliative care services and did not report adult data separately, reported on referrals solely to bereavement services or non-palliative care services, were randomised trials where the intervention influenced the timing of palliative care or were not in the English language.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Three authors (RIJ/CEJ/HLE) independently screened 10% of the titles and abstracts of studies identified. Discrepancies in screening inclusion and exclusion were resolved through discussion, and then review by a fourth author (MJA). As concordance between authors was greater than 90%, each author screened a portion of the remaining abstracts alone (assigned randomly and evenly distributed). Full-text articles were assessed for eligibility and, if included, data extraction was performed using a piloted form by three independent authors (RIJ/YE/HLE).

Data were extracted from each study on the following sample and methodological characteristics: country of origin, country level of human development according to the UNDP Development Index, country palliative care development level according to the WHPCA categorisation of palliative care development, study design, number of patients, percentage of patients alive at the end of the study period, summaries of age, gender and ethnicity (% White Caucasian) of study participants, each cohort’s type of disease, type of palliative care service referred to, the geographical level of analysis for each study (local, regional, national, international), the statistical summary of duration in days (mean, median or both) and terminology used to describe the duration of palliative care (survival, referral-to-death, length of stay). We extracted data on the primary outcome of the duration of palliative care before death in days (median or mean). Included study authors were contacted for missing data. Study quality of individual studies was assessed using Hawker’s criteria for reviewing disparate observational data systematically [20]. The criteria consist of 9 items, each with a score of 1–4 (total score of 36). We rated studies with scores of ≤ 18 as poor, 19–27 as fair and > 27 as good, consistent with Boer et al.’s approach [21]. Four authors piloted the criteria with 10% of the included studies, with concordance of > 90% achieved prior to individual allocation of remaining studies (RIJ/MJA/YE/EJC).

Data synthesis and analysis

A meta-analysis was performed to synthesise reporting of the median number of days palliative care was initiated prior to death. We used the median as the preferred measure of central tendency as it is less affected by outliers and better reflects skewed data. The number of days from palliative care initiation to death was reported across the included articles in one of three ways: as a median, as a mean or including both a median and mean value. For studies reporting mean values only, linear regression modelling was used to derive a median value (see Additional file 1: Fig S2). This was calculated through examining the relationship between mean and median values in articles where both values were reported. The trend line was then applied to derive median values where included studies only reported a mean number of days from palliative care initiation to death. We then weighted median values for each study according to the number of study participants it contained. We then combined median values from all studies to calculate a final weighted median value and the interquartile range (IQR) to summarise duration of palliative care.

Additional analyses were performed to investigate the impact of country level of human development (United Nations Development Programme Human Development Index categories of very high, high, medium, low, other), country level of palliative care development (Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance 2011 categorisation of palliative care development using 1, 2, 3a, 3b, 4a, 4b), type of disease (malignant, non-malignant, mixed) and type of setting of the palliative care service (specialist palliative care unit, community/home, combined, general hospital ward, unspecified) on the duration of palliative care. We used the Mann-Whitney U test to compare the distribution of medians using a significance level of p = 0.05.

Sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the robustness of the primary outcome. Sensitive analyses were undertaken to determine the impact of the characteristics of included studies on the overall weighted median duration of palliative care derived from all studies. A number of characteristics were identified for sensitivity analysis. These included studies where the mean duration of palliative care had been converted to a median value, studies with small sample sizes (< 100 participants), studies analysing local and regional data (defined as ≥ 1 centres in the same geographical region within one country), studies reporting > 5% survival at the end of the study period, studies reporting length-of-stay in palliative care units and studies with poor/fair ratings for methodological quality. For each characteristic included in the sensitivity analyses, we identified all studies with the characteristic of interest (e.g. studies with small sample sizes < 100 participants), removed data from all studies with the characteristic, and then recalculated the final weighted median value with interquartile range (IQR) and median absolute deviation (MAD) to summarise duration of palliative care less the data from studies with the characteristic being explored. This enabled us to explore the influence of characteristics of interest on the overall weighted median duration of palliative care. We also conducted a post hoc analysis excluding the USA (United States of America) studies, given differences found between studies from and outside of the USA.

We used IBM SPSS Statistics 22 for data analysis. Reporting is aligned with the PRISMA checklist for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses (see Additional file 2: Table S1).

Results

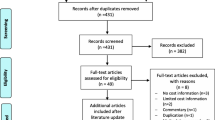

Two thousand six hundred sixty studies were screened, with 169 studies included in the systematic review and meta-analysis. Studies were excluded at the screening stage as their titles/abstracts did not meet the inclusion criteria broadly. Reasons for exclusion at the final eligibility stage are outlined in Fig. 1.

Table 1 summarises the individual characteristics of the included studies. All included studies were used in the meta-analysis.

A table summarising study characteristics can be found in Additional file 2: Table S1. The total number of study participants was 11,996,479. Eighty-eight per cent of studies were observational and retrospective, and most studies were descriptive rather than analytical. The source of publications was predominantly the USA, which accounted for 85% of studies and 97% of participants. Most studies (and 99% of participants) were from very high development countries (94%) and those with the greatest level (4b) of palliative care development (83%). Patients had a weighted mean age of 81.7 years with an equal distribution of males-to-females. Ethnicity was only reported in 38% of studies, stating 88% of study participants as white Caucasian. Most studies reported patients with malignant (50%) or non-malignant disease (12%). However, studies that reported a combined case-mix (35%) covered 91% of total participants. Similarly, half of the studies reported on specific types of palliative care services (31% SPCU, 11% community/home and 7% hospital), with studies reporting in combined settings (50%) accounting for 95% of all participants.

Of all included articles, 46 (27%) were length-of-stay studies. The proportion of patients alive at the end of each study is outlined in Table 1. In 28 of the length-of-stay studies (60.9%) fewer than 10% of patients were alive, with 22 (47.8%) having no patients alive at the end of study.

Study quality was rated as good in 73 (43%) studies, fair in 90 (53%) and poor in 5 (3%). Studies rated as good accounted for 64% of total participants although studies variably summarised the duration of palliative care with inconsistent measures of spread. A table of individual study quality appraisals can be found in Additional file 2: Table S3.

The weighted median duration of palliative care until death was 18.9 days (IQR 0.09, Table 2). Three studies had more than one million participants each [48, 113, 159]. The median duration of palliative care excluding these studies (total 16.7% participants) was 19.2 days (IQR 15). The weighted median duration in days until death per country, by service type, disease type, WHPCA level of palliative care development, and UNDP Human Development Index is reported in Table 2.

Analyses of the influence of study characteristics on the overall weighted median duration of palliative care until death are outlined in Additional file 2: Table S4. Studies rated as poor and fair did not significantly adjust the duration of palliative care for the whole dataset, but they significantly reduced the duration of palliative care when looking at non-USA studies alone. Studies tended to report longer mean than median durations where both were used, reflecting positively skewed data. Studies in which mean durations were converted to medians did not affect the outcome for the whole dataset, but did significantly increase the duration of palliative care for non-USA studies. Even excluding studies with more than one million participants did not greatly alter the duration of palliative care (i.e. 19.2 days).

The spread of median duration of palliative care values according to sample size is demonstrated in Figs. 2 and 3.

Figure 2 outlines the difference in median days duration of palliative care prior to death according to country level of human development and palliative care development. Studies from countries with a very high level of human development had a shorter duration of palliative care than less developed countries (18.9 vs. 34.0 days, p < 0.001). Similarly, as shown in Fig. 3, studies from countries with the greatest level of palliative care development had a shorter duration of palliative care than countries with lower levels (18.9 vs. 28.0 days, p < 0.001). Not all studies reported duration of palliative care for patients with both malignant and non-malignant disease, and across a combination of palliative care settings. Consequently, we conducted sub-analyses using data on the type of disease available in 105 of the included studies (i.e. 62.1%) and the type of palliative care setting using data from 82 studies (i.e. 48.5%). The median duration of palliative care was nine days longer for studies reporting on patients with malignant disease compared with non-malignant disease (15.0 vs. 6.0, p < 0.001). Studies conducted in specialist palliative care units and community/home settings reported a similar duration of palliative care, both longer than in general hospital ward settings (19.2 vs. 20.0 vs. 6.0 days, respectively, p < 0.001). A further sub-analysis, comparing data from the USA and non-USA countries, was performed given the preponderance of data from the former. The median duration of palliative care in studies from the USA was ten fewer days than in non-USA studies (18.9 vs. 29.0, p < 0.001).

The median duration of palliative care was unaffected by studies reporting local or regional data, reporting duration of palliative care as a mean solely, reporting length-of-stay, studies with < 100 participants and studies rated as fair or poor quality. It was, however, reduced to 14.71 days (IQR 0.83; MAD 8.23) after excluding studies with > 5% participants alive at the end of the study period. Sensitivity analysis showed that studies rated as poor and fair did not significantly adjust the duration of palliative care for the whole dataset, but they significantly reduced the duration of palliative care when looking at non-USA studies alone.

Given differences between studies from and outside of the USA, we hypothesised that non-USA studies may have different factors influencing the duration of palliative care. We conducted additional analyses excluding USA data (Additional file 2: Tables S4 and S5). Studies from non-USA countries with a very high level of human development still had a shorter duration of palliative care than less developed countries (29.0 vs. 34.0 days, p < 0.001). However, studies from non-USA countries with the greatest level of palliative care development had a longer duration of palliative care than countries with lower levels of palliative care development (68.9 vs. 28.0 days, p < 0.001). Studies involving patients with malignant disease reported a longer duration of palliative care than those with non-malignant disease; however, the difference was smaller (28.0 vs. 24.3 days, p < 0.001). Studies conducted in community or home settings had a longer duration of palliative care than those conducted in specialist palliative care units and general hospital ward settings (47.9 vs. 14.8 vs. 6.0 days, respectively, p < 0.001).

The sensitivity analyses showed the median duration of palliative care for non-USA studies was unaffected by length-of-stay, studies with < 100 participants, and studies with > 5% of cohorts alive at the end of the study periods. However, it was reduced to 28.0 days after excluding local and regional studies (IQR 1.00; MAD 8.00) and studies reporting duration of palliative care as a mean solely (IQR 20.00; MAD 14.00) and was increased to 48.0 days (IQR 39.88; MAD 25.41) after excluding poor/fair quality studies.

Discussion

In this systematic review, 169 studies were included, involving 11,996,479 patients. 43% of studies were of good quality and studies variably summarised duration of palliative care with inconsistent measures of spread. Internationally, half of all patients accessing palliative care services are referred less than 19 days before death, although we found very large diversity in the median duration of palliative care in days prior to death across the countries in this review, from 6 days in Australia to 69 days in Canada. The median number of days of palliative care prior to death for all US studies was 19 days, and for all non-US studies, it was 29 days. Cancer patients have a longer duration of palliative care as compared with those with non-malignant disease. We found palliative care duration is comparable for patients referred to specialist inpatient units and community settings, but significantly longer than for patients in a general hospital ward. At a country level, human development index level and the extent of palliative care development had an unexpected negative effect on the duration of palliative care.

This large systematic review and meta-analysis of international data found the duration of palliative care before death for patients with life-limiting illness is much shorter (i.e. a median of 19 days) than is supported by research evidence and widely advocated in health care policy. Davis et al.’s systematic review of randomised trials of early integration of outpatient and home palliative care concluded that care must be provided for at least 3–4 months before death to reach maximal benefit [5]. Although we appreciate duration and content of palliative care should be guided by individual patient needs without a one-size-fits-all approach, we are concerned that this reflects a gap between the current practice of palliative care in the terminal phase of life and the timely initiation of palliative care, which impacts on the benefit of palliative care for patients and health care services. This work extends previous efforts by the team to understand the duration of hospice-based specialist palliative care in the UK [8]. This review augments the focus to include data across multiple care settings, including hospital, home and the community, alongside novel comparisons of the duration of palliative care across countries internationally.

Variation in the duration of palliative care before death across countries reflected a range from a median of 6 days (Australia) to 69 days (Canada). Whilst this reflects only published data there is stark variation, with duration of palliative care encompassing only a few days prior to death for some countries. Data from countries may, to some extent, reflect the country-specific provision of palliative care. For example, data from the USA reflected patients receiving ten fewer days in palliative care than those in non-USA countries. This may be explained by USA models of care that restrict hospice care to patients with prognoses less than six months and require patients to stop active treatments that may still be beneficial [186]. Given high levels of palliative care development and human development of included non-USA studies, it is likely that these countries are able to offer similar life-prolonging and supportive healthcare interventions as the USA [187].

Longer duration of palliative care for patients with malignant disease compared with those with non-malignant disease, as found in this study, is consistent with a UK report that found patients with cancer were predominantly referred to palliative care services despite only accounting for 29% of deaths in 2012–2013 [188]. Allsop et al. found cancer patients had a significantly longer median duration between referral to UK hospices and death compared with non-cancer patients (53 days vs. 27 days, p < 0.0001) [8]. This occurs despite evidence that palliative care needs and symptom burden are comparable between cancer and non-cancer groups [189, 190]. Although evidence in support of palliative care interventions is predominantly from studies involving patients with cancer, this is emerging for non-cancer groups [4]. Siouta et al. found that guidelines and pathways supporting the integration of palliative care in major non-malignant disease are increasingly involving earlier palliative care integration but lack information on referral criteria [191]. Other barriers to accessing palliative care in this group must be understood in order to improve integration of care.

We found palliative care duration is comparable for patients referred to specialist inpatient units and community settings, but that this was significantly longer than for patients referred as general hospital inpatients. This is consistent with studies comparing the duration of palliative care between outpatient or home palliative care and general hospital settings, and probably reflects greater referrals of patients in the last days of life in the latter setting [10, 55, 64]. Hui et al. found that patients referred to outpatient palliative care had improved end of life care more than those who received inpatient palliative care from mobile teams [55]. It may be appropriate to concentrate efforts to increase the duration of palliative care in outpatient settings, prior to a longer-term goal of increasing duration of palliative care in all settings. Non-USA patients already spend fewer days in specialist palliative care units and more days in community palliative care, which may reflect patient preference, or reduced capacity of and access to inpatient settings [192].

We found a negative correlation between duration of palliative care and country level of human development. For the limited studies that were not categorised as ‘very high’ according to the United Nations Human Development Index, all but one reported data on malignant conditions. The negative correlation may, therefore, partly reflect the longer duration of palliative care for patients with malignant disease found across all studies. However, the extent to which firm conclusions can be drawn regarding the duration of palliative care and country level of human development is limited. Firstly, the predominance of malignant disease does not reflect the current multitude of diseases and symptoms that characterise health conditions requiring palliative care in the context of low and middle-income countries [6]. Secondly, no studies were included from countries classified as ‘low’ using the United Nations Human Development Index. This review highlights the wider need to support increase in research capacity in the context of low and middle-income countries (LMICs) to better understand the provision of palliative care [6]. There remains a disparity of the reporting of palliative care research in LMICs which needs to be prioritised [193]. These are the countries in which the greatest proportional rise in serious health-related suffering is projected to occur [7]. Alongside efforts to, for example, utilise routinely collected datasets to determine the temporal nature of initiating and subsequent duration of palliative care in LMICs [194], efforts to better understand optimal timing and provision of palliative care in these settings is required. It is not appropriate to extrapolate the existing evidence for early referrals, largely from high-income settings, to countries and settings in which palliative care is critically absent and largely a poverty-reduction intervention to lessen significant costs that can be absorbed by the individual, family and local community arising from incurable illnesses [195].

The main strength of this systematic review is the inclusion of a large number of studies with over 11 million participants, giving significant power to our findings. Duration of palliative care was difficult to define due to the range of different palliative care settings and terminology used to describe this outcome measure. We used a complex search strategy including supplementary searching to identify studies that used inconsistent terminology for palliative care and duration of palliative care. It was not possible to use a statistical method to assess heterogeneity or publication bias. However, we conducted sensitivity analyses in order to further interrogate the data and explain any heterogeneity within the data. Limitations included the definition of palliative care services and the use of length-of-stay in our inclusion criteria. Individual studies were unclear on the level of training and experience of palliative care practitioners and services. Therefore, we chose to assume that services self-defining as specialist palliative care were such but may have included some studies from services with less specialist experience. We used length-of-stay in an inpatient specialist palliative care setting as a proxy for the duration of palliative care as many patients are first referred to these settings and die during first admissions. Across half of all length-of-stay studies included in this review, the entire study population had died at the end of the study period. However, we acknowledge that it is increasingly common for patients to have short inpatient admissions for symptom control with eventual discharge. In the UK, 32% of patients admitted to inpatient hospices are discharged [196]. As such this may not fully reflect the breadth of input from palliative care services and patients admitted to inpatient hospices may have had earlier contact with community or hospital palliative care services. Consequently, the use of length-of-stay could underestimate the duration of palliative care. However, our sensitivity analyses showed that studies reporting length-of-stay did not significantly alter the overall duration of palliative care. Studies reporting > 5% survival at the end of the study period significantly increased the duration of palliative care for the whole dataset, suggesting that our main finding may be an overestimation.

Conclusions

This review suggests that duration of palliative care before death for patients with life-limiting illness is much shorter than is supported by research evidence and widely advocated in health care policy. Our study also highlights wide variation at the level of country, across disease types and settings to which patients are referred. This review draws attention to the increasing extent to which palliative care research is capturing the duration and interaction provided to patients and their families. However, to better understand the timing of palliative care provision internationally, we welcome more consistent terminology and methodology, and routine assessment of duration of palliative care from all countries, to allow benchmarking, service evaluation and quality improvement. This could lead to a greater understanding of the duration of palliative care and associated factors. However, we acknowledge that further research is required across all countries to understand the mechanisms influencing differences in the duration of palliative care received, across the levels of patients, caregivers, health professionals, policymakers and the public, and the settings in which care is provided. In particular, there is a need for greater reporting in less developed settings where there is a dearth of related literature and likely to be the greatest need in future [7]. Reducing barriers to accessing palliative care and promoting earlier integration alongside active treatment would maximise benefits to patients before they die and reduce costs to the wider healthcare service.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- LMICs:

-

Low- and middle-income countries

- MAD:

-

Median absolute deviation

- RCTs:

-

Randomised controlled trials

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- USA:

-

United States of America

References

World Health Organisation. Cancer: WHO Definition of Palliative Care, 2019 https://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/. Accessed 29 Apr 2019.

Gaertner J, Siemens W, Meerpohl JJ, et al. Effect of specialist palliative care services on quality of life in adults with advanced incurable illness in hospital, hospice, or community settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2017;357:j2925.

Kavalieratos D, Corbelli J, Zhang D, et al. Association between palliative care and patient and caregiver outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316(20):2104–14.

Gomes B, Calanzani N, Curiale V, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of home palliative care services for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013; Art. No.: CD007760. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007760.pub2.

Davis MP, Temel JS, Balboni T, et al. A review of the trials which examine early integration of outpatient and home palliative care for patients with serious illnesses. Ann Palliat Med. 2015;4(3):99–121.

Knaul FM, Farmer PE, Krakauer EL, et al. Alleviating the access abyss in palliative care and pain relief—an imperative of universal health coverage: the Lancet Commission report. Lancet. 2018;391(10128):1391–454.

Sleeman KE, de Brito M, Etkind S, et al. The escalating global burden of serious health-related suffering: projections to 2060 by world regions, age groups, and health conditions. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(7):e883–92.

Allsop MJ, Ziegler LE, Mulvey MR, et al. Duration and determinants of hospice-based specialist palliative care: a national retrospective cohort study. Palliat Med. 2018;32(8):1322–33.

Baek YJ, Shin DW, Choi JY, et al. Late referral to palliative care services in Korea. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41(4):692–9.

Bennett MI, Ziegler L, Allsop M, et al. What determines duration of palliative care before death for patients with advanced disease? A retrospective cohort study of community and hospital palliative care provision in a large UK city. BMJ Open. 2016;6(12):e012576.

Cheng W-W, Willey J, Palmer JL, et al. Interval between palliative care referral and death among patients treated at a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(5):1025–32.

Christakis NA, Escarce JJ. Survival of Medicare patients after enrollment in hospice programs. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(3):172–8.

Costantini M, Toscani F, Gallucci M, et al. Terminal cancer patients and timing of referral to palliative care: a multicenter prospective cohort study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;18(4):243–52.

Hui D, Kim S-H, Kwon JH, et al. Access to palliative care among patients treated at a comprehensive cancer center. Oncologist. 2012;17(12):1574–80.

Maltoni M, Derni S, Innocenti MP, et al. Description of a home care service for cancer patients through quantitative indexes of evaluation. Tumori J. 1991;77(6):453–9.

McWhinney IR, Bass MJ, Orr V. Factors associated with location of death (home or hospital) of patients referred to a palliative care team. CMAJ. 1995;152(3):361–7.

O'Leary MJ, O'Brien AC, Murphy M, et al. Place of care: from referral to specialist palliative care until death. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2017;7(1):53–9.

Poulose JV, Do YK, Neo PSH. Association between referral-to-death interval and location of death of patients referred to a hospital-based specialist palliative care service. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46(2):173–81.

Tanuseputro P, Budhwani S, Bai YQ, et al. Palliative care delivery across health sectors: a population-level observational study. Palliat Med. 2017;31(3):247–57.

Hawker S, Payne S, Kerr C, et al. Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Qual Health Res. 2002;12(9):1284–99.

den Boer K, de Veer AJ, Schoonmade LJ, et al. A systematic review of palliative care tools and interventions for people with severe mental illness. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):106.

Aeckerle S, Moor M, Pilz LR, et al. Characteristics, treatment and prognostic factors of patients with gynaecological malignancies treated in a palliative care unit at a university hospital. Onkologie. 2013;36(11):642–8.

Alsirafy SA, Galal KM, Abou-Elela EN, et al. The use of opioids at the end-of-life and the survival of Egyptian palliative care patients with advanced cancer. Ann Palliat Med. 2013;2(4):173–7.

Bakitas M, MacMartin M, Trzepkowski K, et al. Palliative care consultations for heart failure patients: how many, when, and why? J Card Fail. 2013;19(3):193–201.

Beernaert K, Cohen J, Deliens L, et al. Referral to palliative care in COPD and other chronic diseases: a population-based study. Respir Med. 2013;107(11):1731–9.

Cheung WY, Schaefer K, May CW, et al. Enrollment and events of hospice patients with heart failure vs. cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45(3):552–60.

Corbett CL, Johnstone M, Trauer JM, et al. Palliative care and hematological malignancies: Increased referrals at a comprehensive cancer centre. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(5):537–41.

D'Angelo D, Chiara M, Vellone E, et al. Transitions between care settings after enrolment in a palliative care service in Italy: a retrospective analysis. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2013;19(3):110–5.

Dong XQ, Simon MA. Association between elder self-neglect and hospice utilization in a community population. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;56(1):192–8.

Eti S, O'Mahony S, McHugh M, et al. Outcomes of the acute palliative care unit in an academic medical center. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2014;31(4):380–4.

Gerber PS. Last watch: developing an inpatient palliative volunteer program for US veterans in hospice. Omega-J Death Dying. 2013;67(1-2):87–95.

Harris P, Wong E, Farrington S, et al. Patterns of functional decline in hospice: what can individuals and their families expect? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(3):413–7.

Hussain J, Adams D, Allgar V, et al. Triggers in advanced neurological conditions: prediction and management of the terminal phase. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2014;4(1):30–7.

Kelley AS, Deb P, Qingling D, et al. Hospice enrollment saves money for medicare and improves care quality across a number of different lengths-of-stay. Health Aff. 2013;32(3):552–61.

Mack JW, Chen K, Boscoe FP, et al. Underuse of hospice care by medicaid-insured patients with stage IV lung cancer in New York and California. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(20):2569–79.

Meng HD, Dobbs D, Wang S, et al. Hospice use and public expenditures at the end of life in assisted living residents in a Florida Medicaid Waiver Program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(10):1777–81.

Mercadante S, Valle A, Sabba S, et al. Pattern and characteristics of advanced cancer patients admitted to hospices in Italy. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(4):935–9.

Nabal M, Barcons M, Moreno R, et al. Patients attended by palliative care teams: are they always comparable populations? SpringerPlus. 2013;2(1):177.

Nevadunsky NS, Spoozak L, Gordon S, et al. End-of-life care of women with gynecologic malignancies; a pilot study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013;23(3):546–52.

Pattenden JF, Mason AR, Lewin RJ. Collaborative palliative care for advanced heart failure: outcomes and costs from the ‘Better Together’ pilot study. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2013;3(1):69–76.

Redahan L, Brady B, Smyth A, et al. The use of palliative care services amongst end-stage kidney disease patients in an Irish tertiary referral centre. Clin Kidney J. 2013;6(6):604–8.

Sengupta M, Park-Lee E, Valverde R, et al. Trends in length of hospice care from 1996 to 2007 and the factors associated with length of hospice care in 2007: findings from the National Home and Hospice Care Surveys. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2014;31(4):356–64.

Speer ND, Dioso J, Casner PR. Costs and implications of discarded medication in hospice. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(8):975–8.

Wallace EM, Tiernan E. Referral patterns of nonmalignant patients to an Irish specialist palliative medicine service: a retrospective review. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2013;30(4):399–402.

Weckmann MT, Freund K, Bay C, et al. Medical manuscripts impact of hospice enrollment on cost and length of stay of a terminal admission (Provisional abstract). Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2013;30(6):576–8.

Zdenkowski N, Cavenagh J, Ku YC, et al. Administration of chemotherapy with palliative intent in the last 30 days of life: the balance between palliation and chemotherapy. Intern Med J. 2013;43(11):1191–8.

Zheng NT, Mukamel DB, Caprio TV, et al. Hospice utilization in nursing homes: association with facility end-of-life care practices. Gerontologist. 2013;53(5):817–27.

Bogasky S, Sheingold S, Stearns SC. Medicare’s hospice benefit: analysis of utilization and resource use. Med Medicaid Res Rev 2014; 4(2): published online Jul 29. https://doi.org/10.5600/mmrr.004.02.b03.

Brown AJ, Sun CC, Prescott LS, et al. Missed opportunities: patterns of medical care and hospice utilization among ovarian cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;135(2):244–8.

Ache K, Harrold J, Harris P, et al. Are advance directives associated with better hospice care? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(6):1091–6.

Chai H, Guerriere DN, Zagorski B, et al. The magnitude, share and determinants of unpaid care costs for home-based palliative care service provision in Toronto, Canada. Health Soc Care Community. 2014;22(1):30–9.

Eastman P, Dalton GW, Le B. What does state-level inpatient palliative care data tell us about service provision? J Palliat Med. 2014;17(6):718–20.

Fullerton S. Does the diagnosis of conjunctivitis in palliative inpatients have predictive value for imminent death? J Palliat Med. 2014;17(4):378.

Guay MOD, Tanzi S, Arregui MTS, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of advanced cancer patients who miss outpatient supportive care consult appointments. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(10):2869–74.

Hui D, Kim SH, Roquemore J, et al. Impact of timing and setting of palliative care referral on quality of end-of-life care in cancer patients. Cancer. 2014;120(11):1743–9.

Kang SC, Pai FT, Hwang SJ, et al. Noncancer hospice care in taiwan: a nationwide dataset analysis from 2005 to 2010. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(4):407–14.

Kao CY, Wang HM, Tang SC, et al. Predictive factors for do-not-resuscitate designation among terminally ill cancer patients receiving care from a palliative care consultation service. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47(2):271–82.

Keim-Malpass J, Erickson JM, Malpass HC. End-of-life care characteristics for young adults with cancer who die in the hospital. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(12):1359–64.

Koivu L, Polonen T, Stormi T, et al. End-of-life pain medication among cancer patients in hospice settings. Anticancer Res. 2014;34(11):6581–4.

Obermeyer Z, Makar M, Abujaber S, et al. Association between the medicare hospice benefit and health care utilization and costs for patients with poor-prognosis cancer. JAMA. 2014;312(18):1888–96.

Olmsted CL, Johnson AM, Kaboli P, et al. Use of palliative care and hospice among surgical and medical specialties in the veterans health administration. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(11):1169–75.

Scheffey C, Kestenbaum MG, Wachterman MW, et al. Clinic-based outpatient palliative care before hospice is associated with longer hospice length of service. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;48(4):532–9.

Seow H, Brazil K, Sussman J, et al. Impact of community based, specialist palliative care teams on hospitalisations and emergency department visits late in life and hospital deaths: a pooled analysis. BMJ. 2014;348:g3496.

Sexauer A, Cheng MJ, Knight L, et al. Patterns of hospice use in patients dying from hematologic malignancies. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(2):195–9.

Shin SH, Hui D, Chisholm GB, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients admitted to the acute palliative care unit from the emergency center. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47(6):1028–34.

Unroe KT, Sachs GA, Dennis ME, et al. Hospice use among nursing home and non-nursing home patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(2):193–8.

Wachterman MW, Lipsitz SR, Simon SR, et al. Patterns of hospice care among military veterans and non-veterans. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;48(1):36–44.

Yamagishi A, Morita T, Kawagoe S, et al. Length of home hospice care, family-perceived timing of referrals, perceived quality of care, and quality of death and dying in terminally ill cancer patients who died at home. Support Care Cancer. 2014;23(2):491–9.

Yeung HN, Mitchell WM, Roeland EJ, et al. Palliative radiation before hospice: the long and the short of it. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;48(6):1070–9.

Alsirafy SA, Abou-Alia AM, Ghanem HM. Palliative care consultation versus palliative care unit: which is associated with shorter terminal hospitalization length of stay among patients with cancer? Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2015;32(3):275–9.

Chiang J-K, Kao Y-H, Lai N-S. The impact of hospice care on survival and healthcare costs for patients with lung cancer: a national longitudinal population-based study in Taiwan. Plos One. 2015;10(9):e0138773.

Choi Y, Keam B, Kim TM, et al. Cancer treatment near the end-of-life becomes more aggressive: changes in trend during 10 years at a single institute. Cancer Res Treat. 2015;47(4):555–63.

Colman R, Singer LG, Barua R, et al. Characteristics, interventions, and outcomes of lung transplant recipients co-managed with palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(3):266–9.

Dingfield L, Bender L, Harris P, et al. Comparison of pediatric and adult hospice patients using electronic medical record data from nine hospices in the United States, 2008-2012. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(2):120–6.

Dougherty M, Harris PS, Teno J, et al. Hospice care in assisted living facilities versus at home: results of a multisite cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(6):1153–7.

El-Jawahri AR, Abel GA, Steensma DP, et al. Health care utilization and end of life care for older patients with acute myeloid leukemia receiving supportive care alone. Cancer. 2015;121(16):2840–8.

Gage H, Holdsworth LM, Flannery C, et al. Impact of a hospice rapid response service on preferred place of death, and costs palliative care in other conditions. BMC Palliative Care. 2015;14(1):75.

Gozalo P, Plotzke M, Mor V, et al. Changes in medicare costs with the growth of hospice care in nursing homes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(19):1823–31.

Gu XL, Cheng WW, Chen ML, et al. Palliative sedation for terminally ill cancer patients in a tertiary cancer center in Shanghai, China. BMC Palliat Care. 2015;14(1):5.

Gupte KP, Wu W. Impact of anticholinergic load of medications on the length of stay of cancer patients in hospice care. Int J Pharm Pract. 2015;23(3):192–8.

Hennemann-Krause L, Lopes AJ, Araújo JA, et al. The assessment of telemedicine to support outpatient palliative care in advanced cancer. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13(4):1025–30.

Hui D, dos Santos R, Chisholm G, et al. Bedside clinical signs associated with impending death in patients with advanced cancer: preliminary findings of a prospective, longitudinal cohort study. Cancer. 2015;121(6):960–7.

Kao YH, Chiang JK. Effect of hospice care on quality indicators of end-of-life care among patients with liver cancer: a national longitudinal population-based study in Taiwan 2000-2011. BMC Palliat Care. 2015;14(1):39.

Kim SH, Hwang IC, Ko KD, et al. Association between the emotional status of family caregivers and length of stay in a palliative care unit: a retrospective study. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13(6):1695–700.

Kozlov E, Carpenter BD, Thorsten M, et al. Timing of palliative care consultations and recommendations: understanding the variability. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2015;32(7):772–5.

Lee YJ, Yang JH, Lee JW, et al. Association between the duration of palliative care service and survival in terminal cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(4):1057–62.

Myers J, Kim A, Flanagan J, et al. Palliative performance scale and survival among outpatients with advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(4):913–8.

O'Connor TL, Ngamphaiboon N, Groman A, et al. Hospice utilization and end-of-life care in metastatic breast cancer patients at a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(1):50–5.

Pineau ER. Palliative care for the homeless: an intervention to reduce the healthcare economic cost. WURJ. 2015;5(1):Article 2. https://doi.org/10.5206/wurjhns.2014-15.2.

Zakhour M, Labrant L, Rimel BJ, et al. Too much, too late: Aggressive measures and the timing of end of life care discussions in women with gynecologic malignancies. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;138(2):383–7.

Bauman JR, Piotrowska Z, Muzikansky A, et al. End-of-life care in patients with metastatic lung cancer harboring epidermal growth factor receptor mutations. J Palliat Med. 2016;19(12):1316–9.

Brooks GA, Cronin AM, Uno H, et al. Intensity of medical interventions between diagnosis and death in patients with advanced lung and colorectal cancer: a CanCORS analysis. J Palliat Med. 2016;19(1):42–50.

Brown CL, Hammill BG, Qualls LG, et al. Significant morbidity and mortality among hospitalized end-stage liver disease patients in medicare. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;52(3):412–9.

Cheraghlou S, Gahbauer EA, Leo-Summers L, et al. Restricting symptoms before and after admission to hospice. Am J Med. 2016;129(7):754.e7–754.e15.

Diamond EL, Russell D, Kryza-Lacombe M, et al. Rates and risks for late referral to hospice in patients with primary malignant brain tumors. Neuro Oncol. 2016;18(1):78–86.

Hamano J, Yamaguchi T, Maeda I, et al. Multicenter cohort study on the survival time of cancer patients dying at home or in a hospital: Does place matter? Cancer. 2016;122(9):1453–60.

Jarosek SL, Shippee TP, Virnig BA. Place of death of individuals with terminal cancer: new insights from medicare hospice place-of-service codes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(9):1815–22.

Jegier BJ, O’Mahony S, Johnson J, et al. Impact of a centralized inpatient hospice unit in an academic medical center. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2016;33(8):755–9.

Kierner KA, Weixler D, Masel EK, et al. Polypharmacy in the terminal stage of cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(5):2067–74.

King JD, Eickhoff J, Traynor A, et al. Integrated onco-palliative care associated with prolonged survival compared to standard care for patients with advanced lung cancer: a retrospective review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51(6):1027–32.

Lowe SS, Nekolaichuk C, Ghosh S, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients having single versus multiple patient encounters within a palliative care programme. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2016; published online Feb 04. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2015-000985.

Masman AD, van Dijk M, van Rosmalen J, et al. Bispectral index monitoring in terminally ill patients: a validation study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;52(2):212–20.

Obermeyer Z, Clarke AC, Makar M, et al. Emergency care use and the Medicare hospice benefit for individuals with cancer with a poor prognosis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(2):323–9.

Odejide OO, Cronin AM, Earle CC, et al. Hospice use among patients with lymphoma: impact of disease aggressiveness and curability. J Natl Cancer Inst 2016; 108(1): published online Jan 01. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djv280.

Perri GA, Bunn S, Oh YJ, et al. Attributes and outcomes of end stage liver disease as compared with other noncancer patients admitted to a geriatric palliative care unit. Ann Palliat Med. 2016;5(2):76–82.

Porteous A, Dewhurst F, Gray WK, et al. Screening for delirium in specialist palliative care inpatient units: perceptions and outcomes. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2016;22(9):444–7.

Rosenwax L, Spilsbury K, McNamara BA, et al. A retrospective population based cohort study of access to specialist palliative care in the last year of life: who is still missing out a decade on? BMC Palliative Care. 2016;15(1):46.

Sathornviriyapong A, Nagaviroj K, Anothaisintawee T. The association between different opioid doses and the survival of advanced cancer patients receiving palliative care. BMC Palliative Care. 2016;15(1):95.

Schmalz O, Strapatsas T, Alefelder C, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in palliative care: a prospective study of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus prevalence in a hospital-based palliative care unit. Palliat Med. 2016;30(7):703–6.

Schur S, Weixler D, Gabl C, et al. Sedation at the end of life - a nation-wide study in palliative care units in Austria. BMC Palliative Care. 2016;15(1):50.

Senderovich H, Ip ML, Berall A, et al. Therapeutic touch (R) in a geriatric palliative care unit - a retrospective review. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2016;24:134–8.

Sharma N, Sharma AM, Wojtowycz MA, et al. Utilization of palliative care and acute care services in older adults with advanced cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2016;7(1):39–46.

Stevenson DG, Grabowski DC, Keating NL, et al. Effect of ownership on hospice service use: 2005-2011. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(5):1024–31.

United States Renal Data System. 2016 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. Volume 2: ESRD in the United States. Chapter 14, End-of-life Care for Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease: 2000-2013; pp. S567-602, 2016 https://www.usrds.org/2016/view/v2_14.aspx, Accessed 29 Apr 2019.

Adsersen M, Thygesen LC, Neergaard MA, et al. Admittance to specialized palliative care (SPC) of patients with an assessed need: a study from the Danish palliative care database (DPD). Acta Oncol. 2017;56(9):1210–7.

Chan C, Tapley M. A shorter average length of stay in a UK hospice -- how is this happening? Eur J Palliat Care. 2017;24(1):33–5.

Choi JY, Kong KA, Chang YJ, et al. Effect of the duration of hospice and palliative care on the quality of dying and death in patients with terminal cancer: a nationwide multicentre study. Eur J Cancer Care. 2017;15:15.

de la Cruz M, Yennu S, Liu D, et al. Increased symptom expression among patients with delirium admitted to an acute palliative care unit. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(6):638–41.

Einstein DJ, DeSanto-Madeya S, Gregas M, et al. Improving end-of-life care: palliative care embedded in an oncology clinic specializing in targeted and immune-based therapies. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(9):e729–37.

Forst D, Adams E, Nipp R, et al. Hospice utilization in patients with malignant gliomas. Neuro Oncol. 2017;20(4):538–45.

Fukui N, Golabi P, Otgonsuren M, et al. Demographics, resource utilization, and outcomes of elderly patients with chronic liver disease receiving hospice care in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(11):1700–8.

Harris JA, Byhoff E, Perumalswami CR, et al. The relationship of obesity to hospice use and expenditures: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(6):381–9.

Hoverman JR, Taniguchi C, Eagye K, et al. If we don’t ask, our patients might never tell: the impact of the routine use of a patient values assessment. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(10):e831–7.

Kaufman BG, Sueta CA, Chen C, et al. Are trends in hospitalization prior to hospice use associated with hospice episode characteristics? Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2017;34(9):860–8.

Kelly SG, Campbell TC, Hillman L, et al. The utilization of palliative care services in patients with cirrhosis who have been denied liver transplantation: a single center retrospective review. Ann Hepatol. 2017;16(3):395–401.

Kuchinad KE, Strowd R, Evans A, et al. End of life care for glioblastoma patients at a large academic cancer center. J Neuro Oncol. 2017;134(1):75–81.

Lin HY, Kang SC, Chen YC, et al. Place of death for hospice-cared terminal patients with cancer: A nationwide retrospective study in Taiwan. Chin Med J. 2017;80(4):227–32.

Lustbader D, Mudra M, Romano C, et al. The impact of a home-based palliative care program in an accountable care organization. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(1):23–8.

Masel EK, Schur S, Nemecek R, et al. Palliative care units in lung cancer in the real-world setting: a single institution’s experience and its implications. Ann Palliat Med. 2017;6(1):6–13.

Mercadante S, Adile C, Ferrera P, et al. Characteristics of patients with an unplanned admission to an acute palliative care unit. Intern Emerg Med. 2017;12(5):587–92.

Otsuka M. Factors associated with length of stay at home in the final month of life among advanced cancer patients: a retrospective chart review. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(8):884–9.

Palmer WW, Yuen FK. The impact of hospice patient disease type and length of stay on caregiver utilization of grief counseling: a 10-year retrospective study. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2017;34(9):880–6.

Pellizzari M, Hui D, Pinato E, et al. Impact of intensity and timing of integrated home palliative cancer care on end-of-life hospitalization in Northern Italy. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(4):1201–7.

Rivet EB, Ferrada P, Albrecht T, et al. Characteristics of palliative care consultation at an academic level one trauma center. Am J Surg. 2017;214(4):657–60.

Sanoff HK, Chang Y, Reimers M, et al. Hospice utilization and its effect on acute care needs at the end of life in medicare beneficiaries with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(3):e197–206.

Scaccabarozzi G, Limonta F, Amodio E. Hospital, local palliative care network and public health: how do they involve terminally ill patients? Eur J Public Health. 2017;27(1):25–30.

Schuler MS, Joyce NR, Huskamp HA, et al. Medicare beneficiaries with advanced lung cancer experience diverse patterns of care from diagnosis to death. Health Aff. 2017;36(7):1193–200.

Senel G, Uysal N, Oguz G, et al. Delirium frequency and risk factors among patients with cancer in palliative care unit. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2017;34(3):282–6.

Shah D, Hoffman GR. Outcome of head and neck cancer patients who did not receive curative-intent treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;75(11):2456–64.

Sharp C, Lamb H, Jordan N, et al. Development of tools to facilitate palliative and supportive care referral for patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2017;8(3):340–6.

Taylor JS, Rajan SS, Ning Z, et al. End-of-life racial and ethnic disparities among patients with ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(16):1829–35.

Unroe KT, Bernard B, Stump TE, et al. Variation in hospice services by location of care: nursing home versus assisted living facility versus home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(7):1490–6.

Vayne-Bossert P, Richard E, Good P, et al. Integration of oncology and palliative care: setting a benchmark. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(10):3253–9.

Vinant P, Joffin I, Serresse L, et al. Integration and activity of hospital-based palliative care consultation teams: the INSIGHT multicentric cohort study. BMC Palliative Care. 2017;16(1):36.

Waite K, Rhule J, Bush D, et al. End-of-life care patterns at a community hospital: the rest of the story. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2017;34(10):977–83.

Wang S, Hsu SH, Huang S, et al. Longer periods of hospice service associated with lower end-of-life spending in regions with high expenditures. Health Aff. 2017;36(2):328–36.

Wang X, Knight LS, Evans A, et al. Variations among physicians in hospice referrals of patients with advanced cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(5):e496–504.

Wilson DG, Harris SK, Peck H, et al. Patterns of care in hospitalized vascular surgery patients at end of life. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(2):183–90.

Yim CK, Barrón Y, Moore S, et al. Hospice enrollment in patients with advanced heart failure decreases acute medical service utilization. Circulation. 2017;10(3):e003335.

Akdogan D, Kahveci K. Evaluation of geriatric infections in palliative care center. Turk J Geriatr. 2018;21(4):507–14.

Assareh H, Stubbs JM, Trinh LTT, et al. Variations in hospital inpatient palliative care service use: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2018; published online Nov 08. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2018-001578.

Cho J, Zhou J, Lo D, et al. Palliative and end-of-life care in rheumatology: high symptom prevalence and unmet needs. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2018; published online Nov 02. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.10.020.

Choi JY, Kong KA, Chang YJ, et al. Effect of the duration of hospice and palliative care on the quality of dying and death in patients with terminal cancer: a nationwide multicentre study. Eur J Cancer Care. 2018;27(2):e12771.

de Oliveira Valentino TC, Paiva BSR, de Oliveira MA, et al. Factors associated with palliative care referral among patients with advanced cancers: a retrospective analysis of a large Brazilian cohort. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(6):1933–41.

Dincer M. A retrospective study examining the properties and characteristics of dementia patients in a palliative care center. Turk J Med Sci. 2018;48(3):537–42.

Duff JM, Thomas RM. Impact of palliative chemotherapy and travel distance on hospice referral in patients with stage IV pancreatic cancer: a retrospective analysis within a veterans administration medical center. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2018;35(6):875–81.

Dunn EJ, Markert R, Hayes K, et al. The influence of palliative care consultation on health-care resource utilization during the last 2 months of life: report from an integrated palliative care program and review of the literature. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2018;35(1):117–22.

Gainza-Miranda D, Sanz-Peces EM, Alonso-Babarro A, et al. Breaking barriers: prospective study of a cohort of advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients to describe their survival and end-of-life palliative care requirements. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(3):290–6.

Gidwani-Marszowski R, Kinosian B, Scott W, et al. Hospice care of veterans in medicare advantage and traditional medicare: a risk-adjusted analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(8):1508–14.

Gill TM, Han L, Leo-Summers L, et al. Distressing symptoms, disability, and hospice services at the end of life: prospective cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(1):41–7.

Gurau AJ, Berall A, Karuza J, et al. Primary thromboprophylaxis in individuals without cancer admitted to a geriatric palliative care unit. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(2):346–9.

Hattori Y, Ishiguro H, Miyamori T. Integrated assessment tool for daily activity and symptoms: a useful method to assess terminal cancer patients. Prog Palliat Care. 2018;26(3):129–36.

Hausner D, Kevork N, Pope A, et al. Factors associated with discharge disposition on an acute palliative care unit. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(11):3951–8.

Hung YN, Wen FH, Liu TW, et al. Hospice exposure is associated with lower health care expenditures in taiwanese cancer decedents’ last year of life: a population-based retrospective cohort study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55(3):755–65.

Hutchinson RN, Lucas FL, Becker M, et al. Variations in hospice utilization and length of stay for medicare patients with melanoma. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55(4):1165–1172.e5.

Johnson MO, Frank S, Mendlik M, et al. Utilization of hospice services in a population of patients with Huntington’s disease. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55(2):440–3.

Kaufman BG, Klemish D, Kassner CT, et al. Predicting length of hospice stay: an application of quantile regression. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(8):1131–6.

LeBlanc TW, Egan PC, Olszewski AJ. Transfusion dependence, use of hospice services, and quality of end-of-life care in leukemia. Blood. 2018;132(7):717–26.

Ledoux M, Tricou C, Roux M, et al. Cancer patients dying in the intensive care units and access to palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(5):689–93.

Lo AT, Karuza J, Berall A, et al. Prevalence of dementia in a geriatric palliative care unit. Am J Hospice Palliat Med. 2018;35(5):799–803.

McDermott CL, Bansal A, Ramsey SD, et al. Depression and health care utilization at end of life among older adults with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;56(5):699–708.e1.

Mendieta M, Miller A. Sociodemographic characteristics and lengths of stay associated with acute palliative care: a 10-year national perspective. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35(12):1512–7.

Merchant SJ, Brogly SB, Goldie C, et al. Palliative care is associated with reduced aggressive end-of-life care in patients with gastrointestinal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(6):1478–87.

Mulville AK, Widick NN, Makani NS. Timely referral to hospice care for oncology patients: a retrospective review. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2019;36(6):466–71.

Nazim A, Demers C, Berbenetz N, et al. Patterns of care during the terminal hospital admission for patients with advanced heart failure: a retrospective cohort study. Can J Cardiol. 2018;34(9):1215–8.

O'Hare AM, Hailpern SM, Wachterman M, et al. Hospice use and end-of-life spending trajectories in medicare beneficiaries on hemodialysis. Health Aff. 2018;37(6):980–7.

Rozman LM, Campolina AG, Lopez RVM, et al. Early palliative care and its impact on end-of-life care for cancer patients in Brazil. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(5):659–64.

Shih TC, Chang HT, Lin MH, et al. Differences in do-not-resuscitate orders, hospice care utilization, and late referral to hospice care between cancer and non-cancer decedents in a tertiary hospital in Taiwan between 2010 and 2015: a hospital-based observational study. BMC Palliative Care. 2018;17(1):18.

Shinall MC, Martin SF, Nelson J, et al. Five-year experience of an inpatient palliative care unit at an academic referral center. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2018;35(8):1057–62.

Stephens SL, Cassel JB, Noreika D, et al. Palliative care for inmates in the hospital setting. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2018;36(4):321–5.

Vogl M, Schildmann E, Leidl R, et al. Redefining diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) for palliative care - a cross-sectional study in two German centres. BMC Palliative Care. 2018;17(1):58.

Wadhwa D, Popovic G, Pope A, et al. Factors associated with early referral to palliative care in outpatients with advanced cancer. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(9):1322–8.

Yennurajalingam S, Prado B, Lu ZN, et al. Outcomes of embedded palliative care outpatients initial consults on timing of palliative care access, symptoms, and end-of-life quality care indicators among advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer patients. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(12):1690–7.

Yoo SH, Keam B, Kim M, et al. The effect of hospice consultation on aggressive treatment of lung cancer. Cancer Res Treat. 2018;50(3):720–8.

Ziegler LE, Craigs CL, West RM, et al. Is palliative care support associated with better quality end-of-life care indicators for patients with advanced cancer? A retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(1):e018284.

Morrison RS. Models of palliative care delivery in the United States. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2013;7(2):201–6.

Seymour J, Cassel B. Palliative care in the USA and England: a critical analysis of meaning and implementation towards a public health approach. Mortality. 2017;22(4):275–9.

Dixon J, King D, Matosevic T, et al. Equity in the provision of palliative care in the UK: review of evidence, 2015 https://www.mariecurie.org.uk/globalassets/media/documents/policy/campaigns/equity-palliative-care-uk-report-full-lse.pdf. Accessed 25 Oct 2019.

Bausewein C, Booth S, Gysels M, et al. Understanding breathlessness: cross-sectional comparison of symptom burden and palliative care needs in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cancer. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(9):1109–18.

Moens K, Higginson IJ, Harding R, Euro I. Are there differences in the prevalence of palliative care-related problems in people living with advanced cancer and eight non-cancer conditions? A systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;48(4):660–77.

Siouta N, van Beek K, Preston N, et al. Towards integration of palliative care in patients with chronic heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic literature review of European guidelines and pathways. BMC Palliative Care. 2016;15(1):18.

Higginson IJ, Sen-Gupta G. Place of care in advanced cancer: a qualitative systematic literature review of patient preferences. J Palliat Med. 2000;3(3):287–300.

Pastrana T, Vallath N, Mastrojohn J, Namukwaya E, Kumar S, Radbruch L, Clark D. Disparities in the contribution of low- and middle-income countries to palliative care research. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39(1):54–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.05.023.

Allsop MJ, Kabukye J, Powell RA, Namisango E. Routine data and minimum datasets for palliative cancer care in sub-Saharan Africa: their role, barriers and facilitators. In: Silbermnann M, editor. Palliative Care for Chronic Cancer Patients in the Community: Global Approaches and Future Applications. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2021.

Anderson RE, Grant L. What is the value of palliative care provision in low-resource settings? BMJ Glob Health. 2017;2(1):e000139.

Caper K. Hospice care in the UK 2016: Scope, scale and opportunities, 2016. https://www.hospiceuk.org/docs/default-source/What-We-Offer/publications-documents-and-files/hospice-care-in-the-uk-2016.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed 25 Oct 2019.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Naila Dracup (Information Specialist, Leeds Institute of Health Sciences) for her contributions whilst developing the search strategy.

Funding

This research is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) infrastructure at Leeds. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MIB conceived the idea for the paper. RIJ and MJA designed the search strategy and conducted the literature searches. RIJ, MJA, YE, CEJ, HLE and EJC were involved in study selection, data extraction and quality assessment. RIJ and MJA undertook data analysis. RIJ, MJA, CEJ and MIB drafted the manuscript. All authors edited and agreed the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Fig S1. Example of search strategy as used in MEDLINE. Fig S2. Linear regression model used to compare mean and median values.

Additional file 2:

Table S1. PRISMA checklist. Table S2. Summary of characteristics of studies. Table S3. Individual study quality appraisal using Hawker’s criteria. Table S4. Summary of characteristics of studies (excluding USA data). Table S5. Duration of care with sub-analyses (excluding USA data).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Jordan, R.I., Allsop, M.J., ElMokhallalati, Y. et al. Duration of palliative care before death in international routine practice: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med 18, 368 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-01829-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-01829-x