Abstract

Patients attended by palliative care teams: are they always comparable populations? To answer this question we have compared the basic epidemiological characteristics of patients attended by home palliative care teams (HPCT) in two autonomous regions of Spain.

We carried out a coordinated analytical, observational and prospective study in two Spanish autonomous regions: Aragon and Catalonia. Data were kept during each home care visit according to patients' needs. Inclusion criteria were: advanced cancer, over 18 years old and first contact with a HPCT. The recruitment period was 6 months. Variables included were: Survival time (days), age, sex, primary disease and extension, place of residence. Functional and cognitive state, and co-morbidity. 10 signs/symptoms: asthenia, anorexia, cachexia, dysphagia, xerostomy, dyspnoea, oedemas, level of consciousness, presence of delirium, presence of pressure ulcers and some treatment data. Others variables considered were: responsible team, origin, destination when discharge, date and place of death, number of visits made and duration of monitoring. We developed a comparison between groups by Chi-squared test or the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test and a survival analysis by Kaplan-Meier curves and the logrank test to determine differences between factors. The SPSS version 15.0 software package was used.

698 patients were included, 56.2% from Aragon and 43.8% from Catalonia. 60.3% were males, without differences between the regions. Characteristics relative to age, sex, place of residence and extension of oncological diseases were similar for both groups. We found significant differences between the two populations relative to survival time, co-morbidity, functional state, presence and intensity of a number of symptoms and the treatments, patient monitoring and the their destination after discharge.

We can conclude that palliative care teams cover different profiles of patients with regard to their co-morbidity, functional, cognitive and symptomatic states. It must be pointed that the organization of palliative care services and their experience appears to condition the profile of patients they attend. There is a need of consensus on the basic descriptors for palliative care patients in order to ensure that results will be comparable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cicely Saunders started the modern hospice movement in 1967 with the founding of St Christopher’s Hospice in London (Clark 2000). The development of palliative care in Europe and in Spain has progressed slowly since then (SECPAL 2012; Rocafort 2007).

The European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) carried out a study on the development of palliative care in European countries. The Task Force on the Development of Palliative Care in Europe, headed by Carlos Centeno and David Clark, published its results in the EAPC Atlas Of Palliative Care In Europe (Centeno et al. 2007). For the first time it offered reliable information that enabled the state of palliative care services in the different European countries to be compared (Rocafort & Centeno 2008). This study illustrated the existence of a number of common organizational structures and great diversity in the development of different types of programmes and in the provision of services. These differences are, at least, partly related to the different ways of interpreting the underlying concepts and terms in palliative medicine. In order to make valid comparisons, it is necessary to develop a common language (von Guten 2007).

With this aim, the EAPC published its suggestions for use in Europe of a common terminology following a process of consensus with national associations. Quality standards will be defined based on this terminology of consensus. Guidelines for regulations and standards are necessary not only for health care professionals working in the field of palliative care, but also for those entrusted with taking health-related decisions, who are responsible for providing patients with suitable access to palliative care (Radbruch et al. 2009; Radbruch et al. 2010).

The differences that exist in the organizational framework are transferred to the clinical framework (Currow et al. 2009). Do palliative care teams attend the same type of patients? Can comparisons be made between patients in different regions of the same country or between those of different countries? Does the degree of development of palliative care services influence the characteristics of the patients they attend? There are currently no clear answers to these questions, and although a number of initiatives exist that are trying to reach consensus on the minimum information required to describe some symptoms, there is as yet no standardized practice (Jack et al. 2009; 2010; Knudsen et al. 2009). This fact has great transcendence in research and clinical practice. If populations are not homogeneous, the results of multicentric studies may not be completely conclusive. Will we be able to transfer the results of research carried out in other countries to our patients without local validation?

Therefore, it would seem necessary to seek consensus on the basic descriptors that characterize patient samples, simultaneously with the carrying out of studies that verify similarities and differences in groups of patients attended by different teams in different geographical or cultural areas and/or different countries.

Catalonia and Aragon are two neighbouring autonomous regions with uneven trajectories in palliative care.

Catalonia is an autonomous region with an area of 31,895 km2 located in the north-east of the Iberian Peninsula. It has a population of 7,364,079, which accounts for 15.9% of Spain’s total. The demographic distribution is uneven, oscillating between 1.3 and 17,725 inhabitants per km2. Palliative care services in Catalonia started in 1987 (Centeno et al. 2000) and the regional government of Catalonia produced a pilot plan for the development of palliative care services in 1990 in partnership with the World Health Organization (Sanz 1999; Porta Sales & Albo 1998). This institutional support led to the development of a global palliative care network (Gómez-Batiste et al. 1992): 134 specialist palliative care teams, 59 of which act as home care teams, 28 as hospital support teams and 33 as PCUs in university teaching hospitals and medium-term and long-term care facilities. There are also 6 psychosocial teams and 2 centres that act as observatories (Gómez-Batiste et al. 2007).

The autonomous region of Aragon is also located in the north-east of the Iberian Peninsula. It is the fourth largest of Spain’s autonomous regions in size, with an area of 47,720 km2; however, its low population density of barely 25 inhabitants per km2 is the second lowest in the country. The population of the region does not exceed 1,200,000, although its distribution is closely associated with the location of industry and services. Practically half of the population of Aragon lives in its capital, Zaragoza. Palliative care services began in Aragon in 1990, as the result of the concern felt by a group of primary care practitioners who created the first palliative care protocol in a health centre (Torrubia et al. 1990). The first publicly financed home care support team was set up in 1999 (Instituto Nacional de la Salud 1999). The approval of the National Palliative Care Plan in 2000 fostered the progressive development of new resources (Gobierno de Aragón 2003). Aragon currently has 11 specialist palliative care teams, 8 of which act as home care teams and 1 as a hospital support team; 1 PCU in a medium and long-term care facility; and 1 psychosocial team 2.

A study carried out by the Spanish Ministry of Health established that Catalonia was an autonomous region with an equitable distribution of resources and access times for both home and hospital palliative care. However, Aragon does not have an equitable distribution of resources or isochronal intervention, despite great efforts made to provide home care services in rural areas (Herrera et al. 2012).

This study was developed with the aim of establishing similarities and differences between patients attended by palliative care teams in two Spanish autonomous regions as part of a broader study on prognostic tools in palliative care (Nabal et al. 2010a; Nabal et al. 2010b).

Material and methods

This study forms part of a broader study for the validation and improvement of prognostic models in palliative care. It is therefore a coordinated analytical, observational and prospective study. The recruitment period was 6 months, with monitoring until the patients’ death or 180 days.

The data collected came from all visits made by each palliative care team according to the needs of each patient.

The study was carried out in Aragon and Catalonia. The work was carried out by 8 home care support teams (ESAD) in Aragon and by 5 home care support teams (PADES) in Catalonia.

Sample size: A sample size of 693 patients was defined. The sample was calculated according to published recommendations of 10–15 events for each dichotomous variable, and 10–15 (n-1) for each categorical variable.

Inclusion criteria: patients with advanced cancer, over 18 years of age and first contact with a palliative home care team.

The analysed variables were:

-

Survival time (days).

-

General information: age, sex, primary disease and extension, place of residence.

-

Clinical information: functional state (Karnofsky, Barthel, ECOG), cognitive state (Pfeiffer), co-morbidity (Charlson) and 10 signs/symptoms rated according to their intensity by a categorical scale between 0 a 3 where 0 was non, 1 was slight, 2 was moderate and 3 was severe. The sings and symptoms assessed were: asthenia, anorexia, cachexia, dysphagia, dry mouth, dyspnoea, oedemas, level of consciousness, presence of delirium, presence of pressure ulcers.

-

Treatment-related information: corticosteroids, subcutaneous butterfly needle.

-

Activity information: responsible team, origin, destination when discharge, date and place of death, number of visits made and duration of monitoring.

The categorical variables are expressed as a percentage and the quantitative variables as mean ± standard deviation. The comparison between groups was made by means of the Chi-squared test or the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test according to the variable type.

Survival analysis was made using with Kaplan-Meier curves and the logrank test to determine differences between factors. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

The SPSS version 15.0 software package was used.

Results

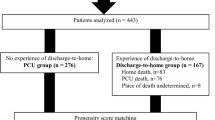

698 patients were included, of which 56.2% were from Aragon and 43.8% were from Catalonia. 60.3% were males, without differences between the regions (Figure 1).

Table 1 shows the general clinical and demographic characteristics of the patients. The sample did not show significant differences by age, gender, place of living or cancer type and stage. The clinical characteristics relative to functional and cognitive state, co-morbidity and treatment can be seen in Table 2. It can be pointed that performance status was better for those patients treated in Catalonia by any performance status scale used. No differences were found on cognitive status or co – morbidity. The use of corticoids and subcutaneous butterfly was greater in Aragon, which may be related to the worse performance status of this sample.

Table 3 shows the similarities and differences related to signs and symptoms. As can be seen globally, the proportion of patients suffering from anorexia, asthenia, dry mouth, dyspnoea or dysphagia did not differ between both places of care; although the highest levels of anorexia, asthenia and dry mouth were more frequent in Aragon. When focusing on signs, Oedemas and level of conscience, were worse in Aragon but higher levels of cachexia and pressure sores were more frequent in Catalonia.

Finally, Table 4 shows the results for activity: responsible team, origin, destination after hospital discharge, date and place of death, number of visits made and duration of monitoring. The number of patients treated by palliative home care teams coming form general practitioners or oncologist were greater in Aragon. On the other hand, the number of patients discharged form palliative care units to home palliative care teams was higher in Catalonia, which may be related to the greater number of PCU in this region. In the same way, the time of follow up was longer in Catalonia. It must be pointed out that patients treated in Aragon got off PC program more than twice comparing with Catalonia.

Regarding the place of death, significant differences were seen (p < 0.001). In Aragon the proportion of patients dead at home was greater (78 vs. 41%). On the other hand, comparing the number of patients died at PCU, this was greater in Catalonia (44 vs. 4%). No significant differences were fond on the percentage of patients who died at acute hospitals between Aragon and Catalonia (18 vs. 15%).

The survival time for both groups is expressed as Kaplan-Meier curves in Figure 2 and was greater in Catalonia.

Discussion

This work illustrates the differences that exist in the characteristics of patients attended by home palliative care teams in two different neighbouring regions in Spain. This work is part of broader research that has the aim of establishing the prognostic values of different symptoms and the impact of repeated measurements on prognostic models (Christakis & Iwashyna 2000; Passik et al. 2004).

Despite the limitations that can arise from a methodology that is not specially designed to establish similarities and differences between these two population groups, the findings obtained invite the reflection. The study involves a broad sample of patients included consecutively. Recruitment was the result of home palliative care services provided by the 13 participating teams. The breadth of the inclusion criteria may justify part of the epidemiological variability, but it does not explain the differences that exist between the two regions. Nevertheless, following along the lines of the work by Currow et al. (2009), our research compiled parameters of co-morbidity, primary disease and functional state, together with basic information on age and sex. However, information related to psychosocial factors were not considered, although the fact that patients remained in their homes is already an indirect factor for requiring basic support.

The patients involved were treated by palliative care teams and had different survival times, a difference that has been maintained over time in favour of Catalonia. This may be explained by the greater development of palliative care services in Catalonia, which began in 1990. The intervention by the Catalan teams seems to be made earlier during the course of the disease, ensuring more prolonged monitoring. This coincides with Currow et al. (2009), who assert that there might be factors related to professional training and staffing that influence patient profiles and which should be described in order for results to be correctly interpreted (Christakis & Iwashyna 2000). Passik et al. (2004) and Rowett et al. (2009) draw attention to the fact that health policy choices influence access to and the development of palliative care services.The fact that health policies are the responsibility of each autonomous region may contribute to enhance the differences. As Christakis points out, in many cases, access to palliative care services is very late and the differences in survival times are seen to be influenced by the primary disease but also by the type of care to which they have access (Christakis & Escarce 1996).

In contrast, the Aragonese population presented a higher mean age, worse functional and cognitive states, and higher rates of co-morbidity, although the differences in this last parameter were not significant. These data may explain the different survival times for the two groups, given that many authors have correlated functional state and co-morbidity with a poor prognosis (Nabal et al. 2002). The existence of differences in survival times of cancer patients between countries has been extensively discussed and seems to bear relation to early diagnosis and the treatments offered (Coleman et al. 2011).

In relation to symptoms, we identified that the prevalence and intensity of symptoms such as asthenia, cachexia and dyspnoea is higher in Catalonia in comparison with Aragon, which presents higher frequencies and intensity in delirium, dry mouth, anorexia and oedemas. Taking into account that mortality is higher in Aragon, the data gathered leads to the suspicion that patients suffering from dyspnoea or intense caquexia leave their homes or do not return to them. The profile of patients attended in Aragon seems to be less complex on the whole from a clinical perspective, but with greater difficulty for access to and attention by palliative care services due to their greater geographical dispersion and the lower number of specialist resources.

Intervention for both groups is made mostly at the request of a general practitioner, particularly in the case of the Catalan population where more than half of the intervention requests came from primary care. It seems that the integration of home palliative care support teams is more consolidated in Catalonia, and it is more common to find general practitioners and home palliative care teams working together. Among the other points of origin, it is of note that patients in the Catalan group come from PCUs, whilst this group is much reduced in Aragon. This could be explained by the fact that there is a support network in Catalonia that covers almost the entire region at all levels of health care, while Aragon has a model based on home care with few long-stay PCUs that is mostly based in large urban areas (Nabal et al. 2010b).

The patients in our sample from Aragon are less commonly located in an urban area, which means that their access to long-stay units is more difficult and less frequent.

There has been growing interest in recent years in describing the organization of palliative care services in different countries (Centeno et al. 2007; Burt et al. 2010; Lynch et al. 2009; Ferris et al. 2009), although populations treated by palliative care teams have not been so accurately compared. Most of the scientific works published in this regard dedicate a section to the description of the population covered by them, but there is no consensus on the minimum essential data, making it difficult to compare the results of such research, or else we run the risk of extrapolating results that are applicable to us to any profile of patient treated by palliative care teams (Currow et al. 2009).

In fact, these findings can be extended to the description of the main symptoms treated in palliative care. The absence of consensus, on the basic descriptors for pain, makes comparison between studies difficult. The systematic reviews concerning cachexia and pain demonstrate that the absence of shared definitions and the different idiomatic connotations attached to descriptors make difficult to generalize the results of research (Knudsen et al. 2009; Fearon et al. 2011; Blue et al. 2011).

There is currently an EAPC research network initiative in progress, in collaboration with the PRISMA project and the European Palliative Care Research Centre (PRC) in Trondheim, Norway, to reach consensus on the minimum set of data capable to describe the population receiving palliative care. This is currently being developed using the Delphi method.

Our work corroborates the need for international consensus in which descriptors for co-morbidity, cognitive and functional state, and the presence or absence of the most prevalent symptoms are contemplated in addition to personal details and particulars of the disease. These data should possibly be complemented with information on the emotional and social/family sphere of patients and the intervention setting. We will only be able to define homogeneous groups and compare the results of our research with a more detailed profile of our patients.

References

Blue D, Omlim A, Barracos VE, Solheim TS, Tan BH, Stoen P: Cancer Cachexia: a systematic literatura review of ítems and domains associated with involuntary weight loss in cancer. Crit Rev Ocol Ematol 2011, 80: 114-144.

Burt J, Plant H, Omar R, Raine R: Equity of use of specialist palliative care by age: cross-sectional study of lung cancer patients. Palliat Med 2010, 24: 641-650. September 10.1177/0269216310364199

Centeno C, Hernansanz S, Flores LA, Sanz Rubilares A, López-Lara F: The reality of palliative care in Spain. Palliative Medicine 2000, 14: 387-394. 10.1191/026921600701536219

Centeno C, Clark D, Lynch T, Rocafort J, Flores LA, Greenwood A: EAPC Atlas of palliative care in Europe. IAHPCPress; 2007.

Christakis NA, Escarce J: Survival of Medicare patients alter enrollment in hospice programs. N Engl J Med 1996, 335: 172-178. 10.1056/NEJM199607183350306

Christakis NA, Iwashyna TJ: Impact of individual and market factors on the timing of initiation of hospice terminal care. Med Care 2000, 38: 528-541. 10.1097/00005650-200005000-00009

Clark D: Palliative history: a ritual process? European J Palliative Care. 2000, 7: 50-55.

Coleman MP, Forman D, Bryant H, Butler J, RAchet B, Maringe C: Cancer survival in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and the UK, 1995.2007 (the International Carcer Benchmarking Partnership): an analysis of population-bases cancer registry data. Lancet 2011, 377: 127-138. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62231-3

Currow DC, Wheeler JL, Glare PA, Kaasa S, Abernethy AP: A framework for generalizability in palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009, 37: 373-386. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.03.020

Fearon K, Strasser F, Anker SD, Boseus I, Bruera E, Fainsinger RL: Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol 2011, 12: 489-495. 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70218-7

Ferris F, Bruera E, Cherny N, Cummings C, Currow D, Dudgeon D: Palliative Cancer Care a Decade Later: Accomplishments, the Need, Next Steps—From the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol 2009, 27: 3052-3058. 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1558

Gobierno de Aragón: RD 207/2003 de 22 de Julio de 2003. BOA nº 96 del 6 de Agosto de 2003 2003, 9220.

Gómez-Batiste X, Borras JM, Fontanals MD, Stjernsward J, Trias X: Palliative care in Catalonia 1990–95. Pal Med 1992, 6: 321-327. 10.1177/026921639200600408

Gómez-Batiste X, Porta-Sales J, Pascual A, Nabal M, Espinosa J, Paz S: Catalonia WHO palliative care demonstration project at 15 Years (2005). J Pain Symptom Manage 2007, 33(5):584-590. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.02.019

Herrera E, Martín V, Fernández F, Ugía JL, Muñoz I, Rodríguez J, Nabal M: Nueva Metodología para la valoración de la equidad y accesibilidad en el desarrollo de recursos de CP. Poster. Congreso de la Sociedad Española de Cuidados Paliativos, Badajoz; 2012.

Instituto Nacional de la Salud: Resolución 26 de Julio de 1999. BOE, nº 190 del 10 de Agosto de 1999. 1999, 29465.

Jack BA, Littlewood C, Eve A, Murphy , Khatri A, Ellershaw JE: Reflecting the scope and work of palliative care teams today: an action research project to modernise a national minimum data set. Pal Med 2009, 23: 80-86.

Knudsen AK, Aass N, Fainsinger R, Caraceni A, Klepstad P, Jordhoy M: Classification of pain in cancer patients: a systematic review. Pal Med 2009, 23: 295-308. 10.1177/0269216309103125

Lynch T, Clark D, Centeno C, Rocafort J, de Lima L, Filbet M: Barriers to the development of palliative care in Western Europe. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009, 37: 305-315. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.03.011

Murray S, Line D, Morris A, Tam G: The quality of death. Ranking end-of-life care across the world. A report from the Economist Intelligence Unit Commisioned by Lien Fundation. London; 2010.

Nabal Vicuña M, Porta Sales J, Naudí Farre C, Altisent Trota R, Tres Sánchez A: Estimación de la supervivencia en Cuidados Paliativos (II): el valor del estado funcional y los síntomas. Medicina Paliativa 2002, 9: 87-95.

Nabal M, Porta J, Naudi C, Altisent R, Tres A: Estimación de la supervivencia en Cuidados Paliativos (III): el valor de la calidad de vida y los factores psicosociales. Medicina Paliativa 2002, 9: 134-138.

Nabal M, Barcons M, Requena A, Bescos M, Busquets X, Torrubia P: Do co-morbidity and symptoms intensity influence survival prognosis? Pal Med 2010, 24(Supplement):S132.

Nabal M, Requena A, Barcons M, Torrubia P, Busquets X, Bescos M: New results on prognosisi at the end of life by homecare suppportive palliative care teams. Pal Med 2010, 24(Supplement):S56.

Passik SD, Ruggles C, Brown G: Is there a model for demonstrating a beneficial financial impact of initiating a palliative care program by an existing hospice program? Palliat Support Care 2004, 2: 419-423.

Porta Sales J, Albo PA: Cuidados Paliativos: Una historia reciente. Medicina Paliativa 1998, 5: 177-185.

Radbruch L, Payne S, and the EAPC Board of Directors: White Paper on standards and norms for hospice and palliative care in Europe: part 1. EJPC 2009, 16(6):278-289.

Radbruch L, Payne S, and the EAPC Board of Directors: White Paper on standards and norms for hospice and palliative care in Europe: part 2. EJPC 2010, 17(1):22-33.

Rocafort J: Estudio del desarrollo y consolidación de los Cuidados Paliativos en Europa a través de la literatura científica bibliometría y revisión sistemática de publicaciones sobre 52 países: 1995–2005. Tesis Doctoral. Universidad de Navarra; 2007.

Rocafort J, Centeno C: EAPC review of Palliative Care in Europe. EAPCPress, Milano; 2008.

Rowett D, Ravenscroft PJ, Ardí J, Currow DC: Using nacional health policies to improve access to palliative care medications in the community. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009, 37: 395-402. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.03.013

Sanz OJ: Historia de la Medicina Paliativa. Medicina Paliativa 1999, 6: 82-88.

SECPAL: Directorio SECPAL de dispositivos de cuidados paliativos. 2012. In Press

Torrubia P, Alvarez T, Planas M, Calvo B, Fernández A, Ballestin R: Programa de asistencia paliativa al enfermo en situación terminal. C.S. Santa Lucía, Zaragoza; 1990.

von Guten CF: The Humpty Dumpty Syndrome. Pal Med 2007, 21: 461. 10.1177/0269216307081943

Acknowledgements

This research would not have been possible without the contribution to recruitment and data collection of all the palliative care teams participant from Aragon: ESAD from Zaragoza Numbers I, II and III; ESAD from Alcañiz; ESAD from Calatayud, ESAD from Teruel; ESAD from Barbastro and ESAD from Huesca Servicio Aragonés de Salud (SALUD). And palliative care teams participant form Catalonia: PADES Granollers, PADES Mataro, PADES Cornella, PADES El Prat and PADES Vilafranca. Institut Català de la Salut (ICS)

We would like to thank patients and professionals for their generous contribution of their precious time and energy.

We would like to thank the Instituto Carlos III for their support.

This work was approved by the Research Ethics Research Committee of Aragon number: C.P. ICS08/0140 – N.E. -CI.PI08/48

This work was financed by a grant from the Health Technologies Evaluation and Health Services Research Agency awarded as part of the assistance for Stategic Health Actions of the Spanish Ministry of Health and Consumer Affairs 2008, Project No. PI08/90055

This work was supported by the Research Committee of the Jordi Gol Primary Care research Institute (IdIAP) and Aragon Health Sciences Institute with the number PI0890106.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MN Participated in the project discussion and design. She coordinated all the research meetings between the two teams. She carried out the result analysis and she wrote all the versions of the manuscript. MB participated in the project discussion and design and coordinated the Catalonian teams work He took part in the camp study by including patients. He participated in the result analysis and reviewed the final manuscript. RM coordinated the Aragon teams work. He took part in the camp study by including patients, and reviewed the final manuscript. XB participated in the project discussion and design and coordinate the Catalonian teams work. He took part in the camp study by including patients, and reviewed the final manuscript. JJT participated in the project discussion and design, developed the statistics and the results analysis and participated in the preliminary and final manuscript. AR was the principal investigator. He had the idea and developed the preliminary and definitive research project. He coordinated and processed all the information. He took part in the preliminary and final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Nabal, M., Barcons, M., Moreno, R. et al. Patients attended by palliative care teams: are they always comparable populations?. SpringerPlus 2, 177 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-1801-2-177

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-1801-2-177