Abstract

Background

The epidemics of HIV and hypertension are converging in sub-Saharan Africa. Due to antiretroviral therapy (ART), more HIV-infected adults are living longer and gaining weight, putting them at greater risk for hypertension and kidney disease. The relationship between hypertension, kidney disease and long-term ART among African adults, though, remains poorly defined. Therefore, we determined the prevalences of hypertension and kidney disease in HIV-infected adults (ART-naive and on ART >2 years) compared to HIV-negative adults. We hypothesized that there would be a higher hypertension prevalence among HIV-infected adults on ART, even after adjusting for age and adiposity.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study conducted between October 2012 and April 2013, consecutive adults (>18 years old) attending an HIV clinic in Tanzania were enrolled in three groups: 1) HIV-negative controls, 2) HIV-infected, ART-naive, and 3) HIV-infected on ART for >2 years. The main study outcomes were hypertension and kidney disease (both defined by international guidelines). We compared hypertension prevalence between each HIV group versus the control group by Fisher’s exact test. Logistic regression was used to determine if differences in hypertension prevalence were fully explained by confounding.

Results

Among HIV-negative adults, 25/153 (16.3%) had hypertension (similar to recent community survey data). HIV-infected adults on ART had a higher prevalence of hypertension (43/150 (28.7%), P = 0.01) and a higher odds of hypertension even after adjustment (odds ratio (OR) = 2.19 (1.18 to 4.05), P = 0.01 in the best model). HIV-infected, ART-naive adults had a lower prevalence of hypertension (8/151 (5.3%), P = 0.003) and a lower odds of hypertension after adjustment (OR = 0.35 (0.15 to 0.84), P = 0.02 in the best model). Awareness of hypertension was ≤25% among hypertensive adults in all three groups. Kidney disease was common in all three groups (25.6% to 41.3%) and strongly associated with hypertension (P <0.001 for trend); among hypertensive participants, 50/76 (65.8%) had microalbuminuria and 20/76 (26.3%) had an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 versus 33/184 (17.9%) and 16/184 (8.7%) participants with normal blood pressure.

Conclusions

HIV-infected adults on ART >2 years had two-fold greater odds of hypertension than HIV-negative controls. HIV-infected adults with hypertension were rarely aware of their diagnosis but often have evidence of kidney disease. Intensive hypertension screening and education are needed in HIV-clinics in sub-Saharan Africa. Further studies should determine if chronic, dysregulated inflammation may accelerate hypertension in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

High blood pressure is the leading risk factor for disease worldwide and accounts for 7% of global disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) and nearly 10 million deaths per year [1]. Despite global declines in blood pressure, the blood pressures of adults in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) continue to rise [2],[3], and the age-adjusted prevalence of hypertension in SSA is estimated to be the highest of any region in the world [4],[5].

HIV remains common in SSA where 69% of HIV-infected persons reside and one in every twenty adults is infected [6]. With half of the eligible HIV-infected persons in SSA on antiretroviral therapy (ART) as of 2010 [7], the infection-related mortality rates have begun to decline and life expectancy has increased [8], which will likely mean more cardiovascular disease mortality among HIV-infected adults as already seen in developed countries [9],[10]. On a population level, in regions with high HIV prevalence, ART-related weight gain among large numbers of HIV-infected adults could lead to an ‘unmasking’ of an epidemic of hypertension and an overall increase in the prevalence of cardiovascular diseases [11].

The impact of HIV and ART on hypertension remains controversial. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that HIV-infected adults in SSA generally have lower blood pressures than uninfected adults [12], and a large, population-based study from South Africa showed that hypertension (particulary stage 2 hypertension) was less common among HIV-infected adults [13], but both studies noted that data were lacking for HIV-infected adults on long-term ART in SSA. ART could lead to hypertension due to weight gain, ART drug toxicities or through an immune-related phenomenon. In the US and Europe, some studies have confirmed higher rates of hypertension among HIV-infected adults on ART compared to uninfected adults [14], but most studies have shown no difference [12],[15]-[18]. In two recent studies from SSA, the prevalence of hypertension among HIV-infected adults was high but, since only HIV-infected adults were enrolled, it remains unclear whether this was due to HIV infection, ART or simply a high community-wide prevalence of hypertension [19],[20]. In addition, although our prior work demonstrated that kidney disease is common among HIV-infected adults in our region [21],[22], the relationship between hypertension and kidney disease (which can be a complication of hypertension, a cause of secondary hypertension or a complication of HIV or ART) remains unknown.

In view of the existing gap in knowledge, we conducted this prospective study to assess the prevalence of hypertension and kidney disease among: 1) HIV-infected, ART-naive adults, 2) HIV-infected adults on ART for >2 years and 3) HIV-negative adults (controls) drawn from the same population. We hypothesized that, compared to HIV-negative controls, hypertension would be more common among HIV-infected adults on ART (even after adjusting for confounders) and would be frequently associated with kidney disease.

Methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional study designed to compare the prevalence of hypertension between HIV-negative adults and two groups of HIV-infected adults.

Study area

The study was conducted in the outpatient HIV clinic of the Bugando Medical Centre (BMC) in Mwanza, Tanzania. BMC is the zonal hospital for the Lake Victoria Zone in northwest Tanzania, serving a population of approximately 13 million. The HIV prevalence in the Lake Zone is 6% [23], similar to the national average. The BMC HIV clinic provides care to 3,500 patients of whom 2,700 are currently on ART. Patients are referred to BMC from surrounding community-based voluntary counseling and testing centers in the city of Mwanza. According to Tanzanian national guidelines, all HIV-infected patients must be assigned a treatment partner who is typically a family member, friend or partner.

HIV-infected patients fulfilling Tanzanian national criteria for ART are started on treatment and are seen monthly or bi-monthly at the BMC clinic. At the time of the study, Tanzanian criteria for starting ART included World Health Organization (WHO) Clinical Stage III disease with CD4 count <350 cells/μl, Stage IV disease regardless of CD4 count, or CD4 count <200 cells/μl. The first-line ART regimen consisted of either tenofovir/emcitrabine or zidovudine/lamivudine + nevirapine or efavirenz. Protease inhibitors (PIs) were only given as second-line ART, in accordance with Tanzanian national guidelines [24].

Study population

Three study groups of non-pregnant adults (>18 years old) were recruited from the BMC HIV clinic:

-

1.

HIV-negative adult treatment partners (the control group),

-

2.

HIV-infected adults enrolled in the last three months and not yet on ART (the HIV-infected, ART-naive group), and

-

3.

HIV-infected adults on ART for >2 years (the HIV-infected, on ART group).

Consecutive HIV-infected adults who met the criteria for study groups 2 or 3 were asked to participate and, if they agreed, their treatment partners were asked to participate in the HIV-negative control group in order to provide a control population with similar socioeconomic status to the two groups of HIV-infected adults. Pregnant women were not eligible for the study. Adults who failed to attend a follow-up visit on the day after enrollment were excluded.

Study procedure

On the day of enrollment, the WHO STEPS questionnaire was administered by the study investigators to determine the prevalence of hypertension and hypertension risk factors [25]. The WHO STEPS questionnaire includes questions regarding prior hypertension testing/diagnosis/treatment, other non-communicable disease and standard protocols for physical examination (as described below). Additional questions were added regarding HIV diagnosis and treatment.

After completing the questionnaire, we conducted a physical examination, including weight and height to assess body mass index (BMI) and waist and hip circumferences. We measured weight to the nearest 0.1 kg using a digital Seca® 813 weight measuring scale (Seca, Hamburg, Germany) with participants wearing minimal clothing and shoes removed. Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a Seca® 213 stadiometer. Waist and hip circumferences were measured twice to the nearest 0.1 cm using a 203 cm Seca® measuring tape. For each of these measurements, the mean of the two values was used.

Blood pressure was measured at least three times over the course of two days by a registered nurse or doctor using a mercury sphygmomanometer. All blood pressure measurements were taken after five minutes of resting quietly and study subjects sat with arm supported at the level of the heart. On the day of enrollment, in accordance with the WHO STEPS protocol [25], at least two measurements were taken one minute apart on alternating arms. If there was >10 mmHg difference in either the systolic and/or diastolic readings, comparing these two readings, further readings were taken until two consecutive measurements were concordant within this range. Average systolic and diastolic pressures were calculated from the last two readings. An additional blood pressure measurement was made on the following day using the same procedure.

Laboratory analysis

At the time of enrollment, venous blood and a clean-catch urine sample were obtained. The CD4 T-cell count was measured using an automated BD FACS Calibur Machine (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). A serum creatinine level was measured using Cobas Integra 400 Plus Analyzer (Roche Diagnostic Limited, Basel, Switzerland). An estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation (without ethnic factor) since this equation is recommended by internationally-recognized Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines and has been shown to be the most accurate eGFR equation for African adults [26]-[28]. Urine samples were tested for microalbuminuria using Micral B Test Strips (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) as used in our prior studies [21],[29]. In order to maximize our specificity, we defined microalbuminuria as a urine albumin concentration of >50 mg/L [30]. In women whose last menstrual period was >1 month prior to the date of study interview, a urine pregnancy test was performed.

Definitions

The primary outcome of this study was hypertension. Hypertension was defined as a sustained elevation of systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥90 mmHg on two different days or current antihypertensive therapy, according to the Joint National Committee 7 (JNC-7) definition [31]. The grade of hypertension was also defined according to JNC-7 using the average of three blood pressure readings: normal is SBP <120 mmHg and DBP <80 mmHg, prehypertension is SBP 120 to 139 mm Hg or DBP 80 to 89 mm Hg, Stage I hypertension is SBP 140 to 159 mm Hg or DBP 90 to 99 mm Hg and Stage II hypertension is SBP >160 mm Hg or DBP >100 mm Hg.

Central obesity was defined as a waist-hip ratio of ≥0.85 for women and waist-hip ratio ≥0.90 for men according to the WHO [25]. Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) was defined as eGFR <60 mL/minute and/or microalbuminuria according to KDIGO [26].

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome of the study was hypertension (as defined above). The primary study analysis was to compare the prevalence of hypertension between each HIV-infected group and the HIV-negative control group. According to a recent population-based survey, 17% of adults in Mwanza city have hypertension (Kavishe BB, Mwanza Interventional Trials Unit, personal communication) and we hypothesized that 30% of HIV-infected adults on ART would have diabetes mellitus. Using Fishers exact test, we calculated that 150 patients in each group would provide 80% power to detect this difference for P <0.05.

Data analysis was done using STATA version 11 (San Antonio, TX, USA). Descriptive statistics were computed by determining median [interquartile range] for continuous variables and proportions (percentages) for categorical variables. Differences between medians were determined using the rank sum test and differences between proportions were determined using Fisher’s exact test. For ordered categorical variables, the nonparametric test for trend was used. P-values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Multiple logistic regression models were performed in order to determine whether the relationship between HIV status and hypertension could be explained by confounding. All baseline characteristics, including past or current exposure to individual ART drugs, were evaluated by a pre-determined, minimally adjusted logistic regression model adjusting for age and sex (since these were expected to differ between groups). Additional, pre-determined multivariable analyses were performed to adjust for BMI and waist-hip ratio (since these were the factors most highly expected to explain differences in hypertension prevalence between groups) as well as fully-adjusted models including all variables with a P-value of <0.05 by minimally adjusted multivariate analysis. BMI and waist-hip ratio were not included together in any models due to collinearity. Variables associated with HIV infection and ART use were not included in the multivariable models due to collinearity with the group variables and the smaller number of subjects with these additional variables. For associated factors, odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were determined. The likelihood ratio test was used to compare the logistic regression models. We also performed multivariable linear regression to determine factors associated with increased SBP and DBP, including all of the same variables that were included in the best-fit multivariable logistic regression model.

Ethical issues

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at BMC and Weill Cornell Medical College. All study participants were informed about the study by a nurse or doctor fluent in Kiswahili and provided written informed consent before participation. All results were made available to clinicians and recorded in the patient’s file. Disease management was conducted by the health care workers of the HIV clinic according to BMC and Tanzanian management protocols.

Results

Enrollment

Between October 2012 and April 2013, 488 consecutive adults were screened. Seven were pregnant (three HIV-infected ART-naive and four HIV-infected on ART), leaving 481 eligible adults. A total of 454/481 (94%) of eligible adults were enrolled: 153 HIV-negative adults (controls), 151 HIV-infected ART-naive adults and 150 HIV-infected adults on ART. Twenty-seven were excluded from the study because they did not return for follow-up testing (eleven HIV-negative controls, nine HIV-infected ART-naive, seven HIV-infected on ART).

Baseline characteristics

Table 1 is a summary of the baseline characteristics of the three groups.

The characteristics of the three groups were broadly similar. Notable differences included that HIV-infected adults on ART were slighly older (median age 40 [38 to 47] years versus 38 [32 to 46] years and 37 [32 to 44] years in the other two groups), more female (76.7% versus 61.4% and 58.9% in the other two groups) and had a higher prevalence of central obesity (52.0% versus 29.1% and 37.1%). HIV-infected, ART-naive adults, on the other hand, had lower mean BMI (22.0 [20.2 to 24.3] kg/m2 versus 23.8 [22.3 to 25.8] and 23.7 [21.5 to 27.9]) and were severely immunosuppressed (mean CD4 T-cell count 215 [150 to 321] cells/ul versus 378 [263 to 521] in the group on ART).

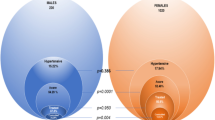

Hypertension outcomes

Table 2 shows hypertension outcomes in the three groups. The prevalence of hypertension in the 153 HIV-negative controls was 25/153 (16.3%). The prevalence of hypertension was lowest in the 151 HIV-infected, ART-naive group (8/151 (5.3%), P = 0.003) and highest in the 150 HIV-infected adults on ART >2 years (43/150 (28.7%), P = 0.01). The median SBP and DBP were both lower in the HIV-infected, ART-naive group (P = 0.007 and P = 0.04, respectively). The grade of hypertension was also higher among the HIV-infected adults on ART versus controls (P = 0.01 for trend).

Rates of hypertension awareness ranged from 3/25 (12%) and 1/8 (12.5%) in the control and HIV-infected, ART-naive group to 11/43 (25.6%) in the HIV-infected on ART group. Rates of current hypertension treatment ranged from none in the control and HIV-infected, ART-naive groups to 7/43 (16.3%) in the HIV-infected on ART group. Rates of hypertension control ranged from none in the control and HIV-infected, ART naive groups to 1/43 (2.3%) in the HIV-infected on ART group. Among HIV-negative controls, 86/153 (56.2%) reported never having had their blood pressure checked and only 40/153 (26.1%) reported having their blood pressure checked within the last year. Rates of prior blood pressure testing were similar in HIV-infected, ART-naive adults (83/151 (55.0%) never checked and 41/151 (27.2%) checked in last year, P = 0.82) but slightly higher among HIV-infected adults on ART (64/150 (42.7%) and 47/150 (31.3%) respectively, P = 0.04).

Factors associated with hypertension

Table 3 shows the factors associated with hypertension by predetermined, partially adjusted multivariable analysis (adjusted for age and sex). As shown, age (OR = 1.07 [1.04 to 1.09]), vigorous work (OR = 0.33 [0.13 to 0.88]), current alcohol use ≥ once/week (OR = 0.13 [0.02 to 0.99]), and BMI (OR = 1.09 [1.03 to 1.15]) were all associated with hypertension. Current CD4 T-cell count (OR = 4.33 [1.51 to 12.40] for CD4 T-cell count >500cells/μL versus <200cells/μL) was also significantly associated with hypertension. Of note, the current CD4 T-cell count was also associated with both SBP and DBP by linear regression (β = 0.022 [0.014 to 0.029], P <0.001 and β = 0.011 [0.006 to 0.017], P <0.001, respectively).

Among variables that were only available for HIV-infected adults on ART, only the use of protease inhibitors (OR = 3.14 [1.10 to 8.98]) was significantly associated with hypertension by logistic regression adjusted for age and sex. The following variables were not significantly associated with hypertension: duration of ART (OR = 1.017 [0.999 to 1.034]), zidovudine use (OR = 0.81 [0.39 to 1.70]), stavudine use (OR = 0.97 [0.46 to 2.04]), tenofovir use (OR = 1.26 [0.59 to 2.70]), efavirenz use (OR = 0.84 [0.39 to 1.75]), and nevirapine use (OR = 1.13 [0.51 to 2.51]).

Table 4 displays the multivariable models used to estimate the impact of HIV and ART status on hypertension status. HIV-infected adults on ART had a significantly higher risk of hypertension than HIV-negative controls, even after adjusting for differences in age and sex (OR = 2.13 [1.18 to 3.85]). Further adjustment for BMI, waist-to-hip ratio, vigorous work and alcohol use did not change these estimates. In contrast, HIV-infected, ART-naive adults had a significantly lower risk of hypertension, even after adjustment for difference in age and sex (OR = 0.32 [0.14 to 0.75]). Further adjustment for BMI, waist-to-hip ratio, vigorous work and alcohol use did not change these estimates. The likelihood ratio test showed that the model with HIV and ART status, along with age, sex, BMI, vigorous work and alcohol use, best explained the differences in hypertension in this study. By linear regression, adjusting for age, sex, BMI, vigorous work and alcohol use, the HIV-infected, ART-naive group had lower SBP and DBP, but this was only statistically significant for SBP (β = −3.84 [−6.89 to −0.79], P = 0.01 and β = −1.96 [−4.09 to 0.17], P = 0.07 respectively). The HIV-infected on ART group had higher SBP and DBP, but this was not statistically significant for either (β = 1.32 [−1.85 to 4.48], P = 0.41 and β = 1.27 [−0.93 to 3.48], P = 0.26, respectively).

Renal disease outcomes

Table 5 displays the renal disease outcomes among the 454 study participants. The overall prevalence of chronic kidney disease among the 153 HIV-negative controls was 25.6%. Among the 150 HIV-infected adults on ART >2 years, the prevalence of chronic kidney disease was 41.3% (P = 0.004 versus the control group) and microalbuminuria was also more common than among controls (58/150 (38.7%) versus 31/153 (20.3%), P = 0.001). None of the commonly used antiretrovirals (ARVs) were significantly associated with chronic kidney disease by Fisher’s exact test (P = 0.73 for tenofovir, P = 0.87 for zidovudine, P = 0.40 for stavudine, P = 1.00 for nevirapine, P = 1.00 for efavirenz, P = 0.08 for protease inhibitors,).

Table 6 shows the association between kidney disease and grade of hypertension both overall and in each of the three study groups. Overall, higher grades of hypertension were associated with higher rates of kidney disease, microalbuminuria and eGFR <60 (P <0.0001 for trend for all three variables). Similar trends were seen in all three study groups.

Discussion

We found that the prevalence of hypertension is high (nearly 30%) among HIV-infected Tanzanian adults on ART for >2 years. In our study, HIV-infected adults on ART had twice the odds of hypertension as HIV-negative controls, even after adjusting for potential confounders, such as age, sex, BMI, waist-hip ratio and vigorous work. HIV-infected adults on ART not only had more hypertension than controls, but also had more severe hypertension (Grade II hypertension – 7% versus 3% of controls). The average blood pressures were not higher among HIV-infected adults on ART, but this is likely because more of the patients in this group were on antihypertensive medications, leading to a reduction in the mean blood pressures. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to compare hypertension prevalence between HIV-infected African adults on long-term ART to HIV-negative adults.

The high prevalence of hypertension among HIV-infected adults on ART could be related to dysregulated inflammation due to immune reconstitution. Inflammation is well recognized as a major part of the pathophysiology of hypertension [32]. Activated CD4+ T-cells infiltrate the kidney and vascular walls in animal models of hypertension [33]. In our study, among HIV-infected adults, the higher CD4+ T-cell counts were associated with more hypertension and higher blood pressures. The prevalence of hypertension was lowest in the group with the lowest average CD4+ T-cell count (HIV-infected ART-naive) and highest in the group in which the CD4+ T-cell count had been low and had then been reconstituted in the setting of ART. Chronic immune activation, including elevated proportions of activated CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells and of T-regulatory cells, irreversible loss of gut mucosal integrity and later destruction of lymph nodes, is known to be common among HIV-infected adults [34]-[36], and may play a key role in the pathophysiology of hypertension among HIV-infected adults on ART in SSA. Chronic inflammation has been shown to persist even after initiation of ART [37]. Even HIV-uninfected adults living in Africa have higher levels of immune activation than their counterparts living in resource-rich settings [38],[39], suggesting that hypertension among adults in SSA, and particularly those with HIV infection on ART, may serve as a model for inflammation-induced hypertension in humans. In order to further test this hypothesis, prospective studies are needed to determine the trajectory of blood pressure changes after ART initiation and associated immunologic and inflammatory markers.

Another possible cause of the higher prevalence of hypertension observed among HIV-infected individuals on ART is a direct or indirect effect of the ARV drugs, but we do not think that this is likely to be the primary explanation. In our study, the duration of ART use was not associated with hypertension. Protease inhibitor use was indeed associated with hypertension but only 10% of subjects had received protease inhibitors and other ARV drugs were not associated with hypertension. Moreover, although protease inhibitor use has been associated with hypertension in one prior study [15], most studies showed no association [17],[19]. In fact, the majority of studies of hypertension among HIV-infected adults on ART have shown no association between hypertension and ART use, regardless of drug class [12],[15]-[18].

We found that the prevalence of hypertension among HIV-infected, ART-naive adults is low (5%). HIV-infected, ART-naive adults had 65% lower odds of having hypertension when compared to HIV-negative controls, even after controlling for possible confounders, such as age, sex, BMI, waist-to-hip ratio and vigorous work. The lower blood pressures that we observed among HIV-infected, ART-naive adults is consistent with the results of a recent, large meta-analysis that showed that HIV-infected adults in SSA (most not on ART) had lower systolic and diastolic blood pressures than controls [12]. The lower rates of hypertension among HIV-infected, ART-naive adults may be explained by HIV-mediated immunosuppression such that immune reconstitution, after the initiation of ART, causes ‘unmasking’ of hypertension in susceptible individuals. Other explanations, such as dysregulation of the sympathetic nervous system, HIV-related hypoadrenalism and side effects of traditional, herbal medicines, have also been proposed [11],[16],[17].

We also noted low rates of hypertension diagnosis, treatment and control. Even among HIV-infected adults who were regularly attending the HIV clinic to receive ART, the rates of hypertension awareness, treatment and control were 25%, 15% and 2%, respectively, and only 30% reported undergoing blood pressure measurement in the last year. Similarly low rates of awareness, treatment, control and testing have been described among community-dwelling adults in other parts of SSA [40],[41], but one might expect that the situation would be better in the context of ongoing HIV care. Possibly, the low hypertension prevalence observed before ART initiation may be creating a false sense of security with regard to hypertension risk among HIV-infected patients and their care-providers. It is also possible that ART may reduce the effectiveness of anti-hypertensive medications (although this is unlikely to be a major factor in our study since very few of our subjects were taking anti-hypertensive medications at the time of enrollment). On the other hand, HIV care provides a good opportunity for chronic hypertension management [20], and regular blood pressure measurement should be considered an essential element of HIV care as we are now seeking to reinforce in our own HIV clinic. Studies from South Africa have shown that, when non-communicable disease care is integrated into HIV care, HIV-infected adults on ART can attain even better functional ability and health status than the general population [37],[42].

Of note, hypertension was also strongly associated with markers of kidney disease in all three study groups; among the 76 total adults with hypertension, 50 (65.8%) had microalbuminuria and 20 (26.3%) had eGFR <60. These findings suggest that the hypertension that we observed in our study is not simply a benign, uncomplicated condition. What remains unclear, however, is whether the hypertension preceded the kidney disease or vice-versa. Kidney disease is known to be common among HIV-infected adults in our region [21] and may be predisposing these adults to the development of hypertension. The kidney disease that we observed among HIV-infected adults on ART does not seem to be related to any specific ART drug based on either this study or our prior work [22].

Study limitations include that enrollment occurred at a single HIV clinic. Our results require validation at other sites. As a government-funded, primary care HIV clinic, though, our patient population is similar to other HIV clinics in our region. In addition, some laboratory tests (such as HIV viral loads) were not available at our center during the study period, but our main study results remain valid even without these variables.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we observed hypertension in nearly 30% of Tanzanian HIV-infected adults on ART treatment and these adults had twice the odds of hypertension compared to HIV-negative controls, even after correcting for differences in age, sex and adiposity. Among the HIV-infected adults with hypertension, 75% were undiagnosed, 85% were untreated and >95% were uncontrolled. Importantly, hypertension was strongly associated with kidney disease in this population. We suggest that aggressive screening, counseling and treatment for hypertension should be instituted in HIV clinics in SSA. Further studies are needed to determine if this hypertension is due to the ART itself or dysregulated inflammation due to immune reconstitution.

Abbreviations

- ART:

-

antiretroviral therapy

- BMC:

-

Bugando Medical Centre

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- CKD:

-

chronic kidney disease

- eGFR:

-

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- IQR:

-

interquartile range

- JNC-7:

-

Joint National Committee 7

- KDIGO:

-

Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- WHR:

-

waist-hip ratio

References

Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, Amann M, Anderson HR, Andrews KG, Aryee M, Atkinson C, Bacchus LJ, Bahalim AN, Balakrishnan K, Balmes J, Barker-Collo S, Baxter A, Bell ML, Blore JD, Blyth F, Bonner C, Borges G, Bourne R, Boussinesq M, Brauer M, Brooks P, Bruce NG, Brunekreef B, Bryan-Hancock C, Bucello C, et al: A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012, 380: 2224-2260. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8.

Twagirumukiza M, De Bacquer D, Kips JG, de Backer G, Vander Stichele R, Van Bortel LM: Current and projected prevalence of arterial hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa by sex, age and habitat: an estimate from population studies. J Hypertens. 2011, 29: 1243-1252. 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328346995d.

Danaei G, Singh GM, Paciorek CJ, Lin JK, Cowan MJ, Finucane MM, Farzadfar F, Stevens GA, Riley LM, Lu Y, Rao M, Ezzati M: The global cardiovascular risk transition: associations of four metabolic risk factors with national income, urbanization, and Western diet in 1980 and 2008. Circulation. 2013, 127: 1493-1502. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001470. 1502e1–8

World Health Organization: A Global Brief on Hypertension. Geneva, Switzerland: 2013.

Danaei G, Finucane MM, Lin JK, Singh GM, Paciorek CJ, Cowan MJ, Farzadfar F, Stevens GA, Lim SS, Riley LM, Ezzati M: National, regional, and global trends in systolic blood pressure since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 786 country-years and 5 · 4 million participants. Lancet. 2011, 377: 568-577. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62036-3.

World Health Organization: WHO HIV Fact Sheet. Available at: . 2013., [http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs360/en/index.html]

World Health Organization: Progress Report 2011: Global HIV/AIDS Response. Geneva, Switzerland 2011.

Bor J, Herbst AJ, Newell ML, Bärnighausen T: Increases in adult life expectancy in rural South Africa: valuing the scale-up of HIV treatment. Science. 2013, 339: 961-965. 10.1126/science.1230413.

Bonnet F, Morlat P, Chêne G, Mercié P, Neau D, Chossat I, Decoin M, Djossou F, Beylot J, Dabis F: Causes of death among HIV-infected patients in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy, Bordeaux, France, 1998–1999. HIV Med. 2002, 3: 195-199. 10.1046/j.1468-1293.2002.00117.x.

Palella FJ, Baker RK, Moorman AC, Chmiel JS, Wood KC, Brooks JT, Holmberg SD: Mortality in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era: changing causes of death and disease in the HIV outpatient study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006, 43: 27-34. 10.1097/01.qai.0000233310.90484.16.

Barninghausen T, Welze T, Hosegood V, Batzing-Feigenbaum J, Tanser F, Herbst K, Hill C, Newell M: Hiding in the shadows of the HIV epidemic: obesity and hypertension in a rural population with very high HIV prevalence in South Africa. J Hum Hypertens. 2008, 22: 236-239. 10.1038/sj.jhh.1002308.

Dillon DG, Gurdasani D, Riha J, Ekoru K, Asiki G, Mayanja BN, Levitt NS, Crowther NJ, Nyirenda M, Njelekela M, Ramaiya K, Nyan O, Adewole OO, Anastos K, Azzoni L, Boom WH, Compostella C, Dave JA, Dawood H, Erikstrup C, Fourie CM, Friis H, Kruger A, Idoko JA, Longenecker CT, Mbondi S, Mukaya JE, Mutimura E, Ndhlovu CE, Praygod G, et al: Association of HIV and ART with cardiometabolic traits in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2013, 42: 1754-1771. 10.1093/ije/dyt198.

Malaza A, Mossong J, Bärnighausen T, Newell ML: Hypertension and obesity in adults living in a high HIV prevalence rural area in South Africa. PLoS One. 2012, 7: e47761-10.1371/journal.pone.0047761.

Gazzaruso C, Bruno R, Garzaniti A, Giordanetti S, Fratino P, Sacchi P, Filice G: Hypertension among HIV patients: prevalence and relationships to insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome. J Hypertens. 2003, 21: 1377-1382. 10.1097/00004872-200307000-00028.

Jericó C, Knobel H, Montero M, Sorli ML, Guelar A, Gimeno JL, Saballs P, López-Colomés JL, Pedro-Botet J: Hypertension in HIV-infected patients: prevalence and related factors. Am J Hypertens. 2005, 18: 1396-1401. 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.05.016.

Mattana J, Siegal FP, Sankaran RT, Singhal PC: Absence of age-related increase in systolic blood pressure in ambulatory patients with HIV infection. Am J Med Sci. 1999, 317: 232-237. 10.1097/00000441-199904000-00004.

Bergersen BM, Sandvik L, Dunlop O, Birkeland K, Bruun JN: Prevalence of hypertension in HIV-positive patients on highly active retroviral therapy (HAART) compared with HAART-naïve and HIV-negative controls: results from a Norwegian study of 721 patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003, 22: 731-736. 10.1007/s10096-003-1034-z.

Schutte AE, Schutte R, Huisman HW, van Rooyen JM, Fourie CMT, Malan NT, Malan L, Mels CM, Smith W, Moss SJ, Towers GW, Kruger HS, Wentzel-Viljoen E, Vorster HH, Kruger A: Are behavioural risk factors to be blamed for the conversion from optimal blood pressure to hypertensive status in Black South Africans? A 5-year prospective study. Int J Epidemiol. 2012, 41: 1114-1123. 10.1093/ije/dys106.

Bloomfield GS, Hogan JW, Keter A, Sang E, Carter EJ, Velazquez EJ, Kimaiyo S: Hypertension and obesity as cardiovascular risk factors among HIV seropositive patients in Western Kenya. PLoS One. 2011, 6: e22288-10.1371/journal.pone.0022288.

Mateen FJ, Kanters S, Kalyesubula R, Mukasa B, Kawuma E, Kengne AP, Mills EJ: Hypertension prevalence and Framingham risk score stratification in a large HIV-positive cohort in Uganda. J Hypertens. 2013, 31: 1372-1378. 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328360de1c.

Msango L, Downs JA a A, Kalluvya SE, Kidenya BR, Kabangila R, Johnson WD, Fitzgerald DW, Peck RN: Renal dysfunction among HIV-infected patients starting antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2011, 25: 1421-1425. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328348a4b1.

Mpondo BC, Kalluvya SE, Peck RN, Kabangila R, Kidenya BR, Ephraim L, Fitzgerald DW, Downs JA: Impact of antiretroviral therapy on renal function among HIV-infected Tanzanian adults: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2014, 9: e89573-10.1371/journal.pone.0089573.

Tanzanian Commission on AIDS: HIV/AIDS and Malaria Indicator Survey 2011–12. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania 2013.

National AIDS Control Program: National Guidelines for the Management of HIV/AIDS. 3rd edition. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania 2009.

World Health Organization: WHO STEPS Instrument. Geneva, Switzerland 2012.

KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013, 3: 1-150.

Van Deventer HE, George JA, Paiker JE, Becker PJ, Katz IJ: Estimating glomerular filtration rate in black South Africans by use of the modification of diet in renal disease and Cockcroft-Gault equations. Clin Chem. 2008, 54: 1197-1202. 10.1373/clinchem.2007.099085.

Wyatt CM, Schwartz GJ, Owino Ong’or W, Abuya J, Abraham AG, Mboku C, M’mene LB, Koima WJ, Hotta M, Maier P, Klotman PE, Wools-Kaloustian K: Estimating kidney function in HIV-infected adults in Kenya: comparison to a direct measure of glomerular filtration rate by iohexol clearance. PLoS One. 2013, 8: e69601-10.1371/journal.pone.0069601.

Janmohamed MN, Kalluvya SE, Mueller A, Kabangila R, Smart LR, Downs JA, Peck RN: Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in diabetic adult out-patients in Tanzania. BMC Nephrol. 2013, 14: 183-10.1186/1471-2369-14-183.

Hasslacher C: Clinical significance of microalbuminuria and evaluation of the Micral-Test. Clin Biochem. 1993, 26: 283-287. 10.1016/0009-9120(93)90126-Q.

Chobanian AA, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT, Roccella EJ: Seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension. 2003, 42: 1-104. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2.

Harrison DG, Guzik TJ, Lob HE, Madhur MS, Marvar PJ, Thabet SR, Vinh A, Weyand CM: Inflammation, immunity, and hypertension. Hypertension. 2011, 57: 132-140. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.163576.

Harrison DG, Marvar PJ, Titze JM: Vascular inflammatory cells in hypertension. Front Physiol. 2012, 3: 1-8. 10.3389/fphys.2012.00128.

Hunt PW, Cao HL, Muzoora C, Ssewanyana I, Bennett J, Emenyonu N, Kembabazi A, Neilands TB, Bangsberg DR, Deeks SG, Martin JN: Impact of CD8+ T-cell activation on CD4+ T-cell recovery and mortality in HIV-infected Ugandans initiating antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2011, 25: 2123-2131. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834c4ac1.

Lim A, Tan D, Price P, Kamarulzaman A, Tan HY, James I, French MA: Proportions of circulating T cells with a regulatory cell phenotype increase with HIV-associated immune activation and remain high on antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2007, 21: 1525-1534. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32825eab8b.

Ipp H, Zemlin A: The paradox of the immune response in HIV infection: when inflammation becomes harmful. Clin Chim Acta. 2013, 416: 96-99. 10.1016/j.cca.2012.11.025.

Mutevedzi PC, Rodger AJ, Kowal P, Nyirenda M, Newell M: Decreased chronic morbidity but elevated HIV associated cytokine levels in HIV-infected older adults receiving HIV treatment: benefit of enhanced access to care?. PLoS One. 2013, 8: e77379-10.1371/journal.pone.0077379.

Messele T, Abdulkadir M, Fontanet AL, Petros B, Hamann D, Koot M, Roos MT, Schellekens PT, Miedema F, de Wit TF R: Reduced naive and increased activated CD4 and CD8 cells in healthy adult Ethiopians compared with their Dutch counterparts. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999, 115: 443-450. 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00815.x.

Clerici M, Butto S, Lukwiya M, Saresella M, Declich S, Trabattoni D, Pastori C, Piconi S, Fracasso C, Fabiani M, Ferrante P, Rizzardini G, Lopalco L: Immune activation in africa is environmentally-driven and is associated with upregulation of CCR5: Italian-Ugandan AIDS Project. AIDS. 2000, 14: 2083-2092. 10.1097/00002030-200009290-00003.

Dewhurst MJ, Dewhurst F, Gray WK, Chaote P, Orega GP, Walker RW: The high prevalence of hypertension in rural-dwelling Tanzanian older adults and the disparity between detection, treatment and control: a rule of sixths?. J Hum Hypertens. 2013, 27: 374-380. 10.1038/jhh.2012.59.

Kayima J, Wanyenze RK, Katamba A, Leontsini E, Nuwaha F: Hypertension awareness, treatment and control in Africa: a systematic review. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2013, 13: 54-10.1186/1471-2261-13-54.

Nyirenda M, Chatterji S, Falkingham J, Mutevedzi P, Hosegood V, Evandrou M, Kowal P, Newell M: An investigation of factors associated with the health and well-being of HIV-infected or HIV-affected older people in rural South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2012, 12: 259-10.1186/1471-2458-12-259.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health Fogarty Foundation (TW000018) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (K24 AI098627). The study sponsor was not involved in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript. We would like to thank Professor Charles Majinge, the Director General of Bugando Medical Centre, for his administrative support in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

RP, RS, SK, DF and JK designed the study. RS and RP were involved in study enrollment. RP and JT did the analysis. SK, JD, MS, WF and JK provided feedback for the analysis. RP wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Peck, R.N., Shedafa, R., Kalluvya, S. et al. Hypertension, kidney disease, HIV and antiretroviral therapy among Tanzanian adults: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med 12, 125 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-014-0125-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-014-0125-2