Abstract

Introduction

This review explores the characteristics of service delivery-related interventions to improve maternal and newborn health (MNH) in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs) over the last two decades, comparing three common framings of these interventions, namely, quality improvement (QI), implementation science/research (IS/IR), and health system strengthening (HSS).

Methods

The review followed the staged scoping review methodology proposed by Levac et al. (2010). We developed and piloted a systematic search strategy, limited to English language peer-reviewed articles published on LMICs between 2000 and March 2022. Analysis was conducted in two—quantitative and qualitative—phases. In the quantitative phase, we counted the year of publication, country(-ies) of origin, and the presence of the terms ‘quality improvement’, ‘health system strengthening’ or 'implementation science’/ ‘implementation research’ in titles, abstracts and key words. From this analysis, a subset of papers referred to as ‘archetypes’ (terms appearing in two or more of titles, abstract and key words) was analysed qualitatively, to draw out key concepts/theories and underlying mechanisms of change associated with each approach.

Results

The searches from different databases resulted in a total of 3,323 hits. After removal of duplicates and screening, a total of 231 relevant articles remained for data extraction. These were distributed across the globe; more than half (n = 134) were published since 2017. Fifty-five (55) articles representing archetypes of the approach (30 QI, 16 IS/IR, 9 HSS) were analysed qualitatively. As anticipated, we identified distinct patterns in each approach. QI archetypes tended towards defined process interventions (most typically, plan-do-study-act cycles); IS/IR archetypes reported a wide variety of interventions, but had in common evaluation methodologies and explanatory theories; and HSS archetypes adopted systemic perspectives. Despite their distinctiveness, there was also overlap and fluidity between approaches, with papers often referencing more than one approach. Recognising the complexity of improving MNH services, there was an increased orientation towards participatory, context-specific designs in all three approaches.

Conclusions

Programmes to improve MNH outcomes will benefit from a better appreciation of the distinctiveness and relatedness of different approaches to service delivery strengthening, how these have evolved and how they can be combined.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Maternal and newborn mortality remains an important public health concern around the world [1, 2]. Throughout the years, improving maternal and newborn health (MNH) care has remained a global priority [3]. However, despite ongoing efforts and increased access to health services in many low-and middle-income countries (LMICs), goals of reducing maternal and newborn mortality are far from being attained [4, 5]. Additional efforts in recent years have focused not only at broadening health services coverage but also improving the quality of care provided to mothers and newborns [2, 5, 6].

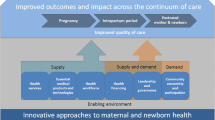

An array of supply-side, health service interventions is being implemented in LMICs to improve MNH care and outcomes [7,8,9]. An initial scan of the literature suggests these cluster around three broad approaches to service delivery strengthening: quality improvement (QI), implementation science/research (IS/IR) and health system strengthening (HSS). The three approaches have different origins. QI applies process improvement methodologies first developed in manufacturing industry to health care [10, 11]; IS/IR emerged from the evidence-based medicine movement, and focuses on the integration of clinical guidelines into health care practice; and HSS came from the field of global health concerned with the wider health system constraints to implementation of disease-specific or programmatic interventions [12,13,14].

These approaches tend to use different intervention designs, concepts, terminologies, frameworks and theories. They operate within distinct professional communities, scientific journals and training streams. They also tend to engage different levels of the health system: QI is typically health facility team based (micro-level); HSS operates at meso and macro level (district, regional or national settings); IS/IR focuses on shaping the behaviour of healthcare users and/or providers while also typically referencing research methodologies such as cluster randomised trials [12, 13]. Although they have different origins and use different methodologies, the three approaches share similar goals, namely, a systematic approach to changing healthcare practice and service delivery [15]. As such, each approach, QI, IS/IR or HSS may offer ideas, concepts and methodologies that when combined could benefit the strengthening of maternal-newborn health services. However, their similarities or differences are often not appreciated or understood, and intervention design choices are seldom explicitly justified or considered in relation to alternatives [16]. Consequently, opportunities to leverage their combined strengths may be missed.

This review forms part of a multi-level service delivery initiative to improve MNH in South Africa, referred to as Mphatlalatsane [17]. In the inception phases of Mphatlalatsane there were debates on how to blend QI, IS/IR and HSS approaches in the design and evaluation of the project. This review was prompted by these debates and conducted to explore the scope of existing evidence on the different approaches to service delivery improvement for MNH and their methodologies and assumptions, to inform the design and/or evaluation of future complex interventions. The rationale for the review thus emerges from a practitioner perspective of decision-making in complex systems, rather than a researcher perspective of advancing knowledge on particular approaches.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review using the methodology proposed by Levac et al. (2010) [18], to map and analyse the literature on MNH service delivery interventions. Building on previous approaches to scoping studies [19], Levac et al.’s framework emphasizes relevance to policy and practice, and the importance of aligning review purpose and research questions to review scope and strategy. This guidance resonated with our review purpose, which arose from real-world intervention design questions, and which led us to ask both objectively measurable (quantitative) and interpretive (qualitative) questions of the review. We adopted the first five stages of the Levac et al. framework (outlined below), leaving out the optional sixth stage (stakeholder consultation). A study protocol was published prior to the conduct of this review [20]. We used the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) as a checklist to guide the screening and reporting [21].

Review aim

This review explores the characteristics of service delivery-related interventions to improve MNH in LMICs over the last two decades, comparing three common framings of these interventions, namely, quality improvement (QI), implementation science/research (IS/IR), and health system strengthening (HSS).

Stage 1: Identifying the research questions

The overarching research question that guided this scoping review was: What are the profiles and characteristics of QI, IR and HSS or interventions used to improve MNH in LMICs?

The sub-questions were:

-

1.

What is the distribution of approaches (QI, IR, HSS or other) in the literature on MNH service delivery interventions?

-

2.

Who are the actors targeted for change in QI, IR or HSS interventions to improve MNH?

-

3.

Who are the (other) health system stakeholders involved in the change processes during QI, IR or HSS interventions to improve MNH?

-

4.

What are the services or systems areas of focus of QI, IR or HSS interventions to improve MNH?

-

5.

What are the key constructs and concepts, frameworks and models, and theories and assumptions underlying QI, IR or HSS interventions to improve MNH?

To aid the search and selection strategy, we specified the concept, target population & health outcomes, as recommended [18] (Table 1). Table 2 provide a definition of key concepts used in the review.

Stage 2: Identifying relevant studies – search strategy

This stage involved an iterative and collaborative process of searching the literature, refining the search strategy, and reviewing articles for study inclusion.

We developed a systematic search strategy using a combination of keywords and Boolean operators (AND/OR) to identify the study’s search strategy prototype. Using this strategy, we searched for English language peer reviewed articles indexed in the following electronic databases: EBSCOhost, PubMed, Web of Science, MASCOT/Wotro Map of Maternal Health Research and Google Scholar advanced search. We limited our initial search to articles published between 2000 and 2020, to capture the growth of interest in the different approaches (QI, IR and HSS) that evolved in the era of MDGs. The search was subsequently updated on 28 March 2022, to include publications in 2021 and early 2022. The search strategy was piloted to check its suitability to selected databases and keywords. A pilot sample search in PubMed is shown in Supplementary Table 1, Additional File 1. We documented each step in the search process, detailing the date, database, keywords, and the number of articles retrieved.

Stage 3: Selection of relevant articles

In addition to the concept, target population and health outcomes framework, inclusion and exclusion criteria guided the selection of studies (Table 3).

Stage 4: Charting the data

A profile of the included articles was completed on an excel spreadsheet, extracting the authors, year of publication, country where the intervention was implemented, and the focus of research (maternal, newborn or both). The articles were also screened for the presence of the terms ‘quality improvement’, 'implementation science’/ ‘implementation research’ or ‘health system strengthening’ in titles, abstracts and keywords. We labelled articles as 'archetypes' when the terms QI and IR were reflected in titles, abstracts, and keywords. As there were fewer HSS papers, we included articles where HSS appeared in at least two of the three dimensions: either in the title and abstract, title and keyword or abstract and keyword. The sub-set of archetypes (n = 55) was further coded qualitatively by two authors (SM and HS) independently, documenting the nature of the intervention, including actors targeted and stakeholders involved, health systems setting, frameworks/theories adopted and key elements of interventions.

The data charting and qualitative coding (completed data sheets) is available on request from the authors.

Stage 5: Collating, summarizing, and reporting of results

Data analysis was conducted in two steps: 1) The full database of 231 articles formed the basis of a descriptive quantitative analysis of publication dates, country(ies) of study and profile and overlap of approaches, conducted in SPSS. 2) The qualitative coding sheets compiled by SM and HS were combined, and through dialogue between the two authors, key characteristics of and patterns in each set of archetypes identified. These were then compared and contrasted with the other archetypes, and implications for policy and practice formulated.

Results

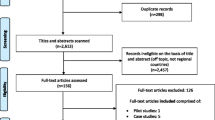

The searches from different databases resulted in a total of 3,323 hits (EBSCOhost = 137, PubMed = 1,475, Web of Science = 1,650, MASCOT/Wotro Map of Maternal Health Research = 37; and citation search = 24). After removal of duplicates and the first two stages of screening, a total of 231 potentially relevant articles remained for data extraction (See flow chart in Fig. 1). The third stage of screening for approaches (QI, IR, HSS) in the title, abstract and keywords led to 57 articles we identified as archetypes for qualitative analysis (Fig. 1).

Distribution of studies reviewed

The distribution of articles by year, country and focus are reported below. From 2012 onwards, there was a steady growth in the number of published articles, plateauing in 2018 (n = 35) and 2019 (n = 34) and dropping to lower levels in 2020/1 (Fig. 2). More than half (n = 134, 58%) were published from 2017 onwards.

The articles reported on interventions in LMICs across the globe, with India (n = 23) and Kenya (n = 21) the most frequently represented (Fig. 3).

The focus of interventions (maternal, newborn or both) shifted over the years: while there was an overall increase in studies in all three categories, the ratio between them changed, from a singular to a combined focus (Fig. 4).

Profile of interventions to strengthen maternal and newborn health services in LMIC papers

Presence of terms in one or more of the title, abstract and keywords showed a preponderance of IR (147 studies with at least one mention), not surprisingly as IS/IR is a generic category encompassing a wide range of approaches [12], followed by QI (86 mentions), and HSS (29 mentions). However, QI approaches were most likely to be referenced in all three elements of the paper (n = 32) compared to 20 for IR/IS and only two for HSS (Supplementary Fig. 1). Twelve percent of papers made no reference to any of the three approaches, using more general descriptors of intervention e.g. strategy, programme or initiative (Supplementary Fig. 2). These studies were picked up by search terms such as ‘health system’ and ‘health system intervention’, but not ultimately classified as HSS or one of the other two approaches.

Studies often referenced more than one approach, most commonly a combination of QI and IR (n = 43). Five studies referenced all three approaches at least once and four papers were classified as archetypes of two approaches.

Qualitative analysis of archetypes

Of the 57 articles identified as archetypes, 55 were analysed qualitatively. Two QI archetypes were excluded as insufficiently information rich. The remaining 55 included 30 articles on QI, 16 articles on IR and 9 articles on HSS approaches, respectively. Four IR archetypes were also archetypes of, and assigned to, the other two categories. The 55 papers were published in 30 general and subject specific journals, with Implementation Science (n = 6), BMC Health Services Research (n = 5) and BMC Reproductive Health (n = 5) being the most common (Supplementary Fig. 3). The papers were a mix of intervention descriptions, process and effectiveness/outcome evaluations (or protocols for these), retrospective case studies of implementation factors and analyses of intervention scale up. They encompassed both qualitative and quantitative methodologies, with a strong influence of (quasi-)experimental designs such as cluster hybrid implementation-effectiveness studies. While the interventions described were all ultimately concerned with shaping frontline health care provider practice, they addressed a range of micro, meso and macro level factors and players, depending on the purpose of the study (e.g. effectiveness, scale up, sustainability) and/or assumptions of change.

Detailed analysis of the MNH service delivery interventions in archetypes of the three approaches revealed distinct patterns but also considerable variation within and overlap between approaches. Table 4 compares the three approaches, including models/frameworks, interventions, key ideas and overall orientations discerned in the studies. QI emerged as the dominant approach from 2019 onwards (see also Supplementary Fig. 4). Studies were distributed across four continents, and most often reported on a single country, in contrast to the HSS studies which were in Africa only, and which included three large multi-country initiatives.

Models and interventions used in included studies

Quality improvement models

The QI studies adopted a mix of models. Many drew on the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) framework [38, 39], also referred to as QI collaboratives [40], or the Breakthrough Series Model [38]. The IHI model is centred on iterative ‘Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA)’ cycles, implemented by frontline health care teams, and has evolved into a multifaceted quality improvement methodology, including diagnostic and monitoring processes and tools, and scale up processes [41]. Drawing on the same core ideas of facility team-based problem identification and PDSA cycles, the WHO Point of Care QI (POCQI) model was the basis of several studies, particularly in India. It was developed by the WHO South East Asian Regional Office (SEARO) specifically for MNH care [42,43,44]. One paper referenced Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI), following a similar approach [45]. A number of QI studies adopted processes of standard setting and regular measurement, such as the Standards Based Management and Recognition (SBM-R) model [26, 46, 47], addressing specific bottlenecks arising from the measurement process. The EQUIP (Enhanced Quality Management using Information Power) study combined standards, measurement and PDSA processes [48]. Similarly, the MESH-QI (Management, Enhanced Supervision for Health Care and QI) combined PDSA cycles with meso-level supportive strategies and training [49]. QI studies drew on explanatory frameworks from the field of IR (see below) such as Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) and the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) [39, 50, 51].

The QI studies addressed both specific issues (e.g. antibiotic usage, thermoregulation in a neonatal ICU, postpartum haemorrhage) and more general problems (e.g. reducing perinatal mortality). The interventions were for the most part focused on micro, facility level teams and participatory processes (PDSA cycles, problem analysis, change ideas, monitoring etc.) [52]. Some also considered meso-level strategies for supporting facility teams [49], while others included participatory processes (‘learning collaboratives’) at district and other levels to scale up QI interventions [53,54,55]. In sum, the overall orientation of the QI interventions was on defined processes aimed at health facility teams with supportive and scale up processes at meso and macro levels.

Implementation research models

In contrast to the QI studies, the IR study interventions were more diverse, with a range of entry points (community and facility based, meso and macro-level, sometimes in combination), and adopting a variety of tools (e.g. e-health, checklists) and mechanisms (e.g. CHWs, financial incentives) (Table 4). Similar to QI studies their interventions included both specific (e.g. birth companions, kangaroo mother care) and multi-faceted packages (combining community and facility-based interventions) [56]. Several were concerned with explaining implementation at scale [57,58,59]. Frameworks guiding change in these studies included the three-level Stages-of-Change model [60]: pre-implementation (readiness of stakeholders), implementation (readiness of system) and institutionalization; and the ‘The Capability, Opportunity, Motivation, Behaviour (COM-B)’ model to implement clinical care bundles for post-partum haemorrhage. COM-B stands for Capability (training, on-site simulations), Opportunities (physical infrastructure and resources), and Motivation (champions, actionable intelligence) for Behaviour [61]. Recognising the importance of adapting interventions to local contexts, the latter included an extensive phase of formative research and co-design of interventions, followed by adaptive cycles of implementation, not unlike a PDSA cycle.

In the main, theories reported in the IR studies were descriptive or explanatory models of change rather than prospective guides to intervention implementation (in contrast to the QI process models). Frameworks included the descriptive account of implementation, such as the RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance) heuristic [62], or constructs such implementation fidelity, acceptability and intervention strength [61,62,63,64]. Several studies sought to explain (non)implementation using frameworks such as the Consolidated Framework Implementation Research (CFIR) [65], The Promotion Action of Research in Health (PARIHS) [58], and Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) [60]. These frameworks provide a structured means for assessing the barriers and facilitators of implementation, and to generate context-specific recommendations for further implementation of evidence-based interventions.

IR studies thus approached the mechanisms and drivers of behaviour and system change with an array of implicit assumptions, with the common goal of testing different ways of achieving evidence-based practice through rigorous and theory-based evaluation designs.

Health systems strengthening models

The HSS Interventions focused on systems-level enablers, implicitly or explicitly drawing on the WHO Health System Building Blocks framework [66], altering system level inputs such as financing, human resource, leadership and governance, infrastructure, supply chain mechanisms and information, sometimes in combination with specific facility-based QI strategies [67]. The Ghana Essential Health Intervention Packages (GEHIP) was a district and regional planning, resource allocation and leadership methodology supporting the implementation of community-based service delivery referred to as CHPS [68]. The rationale for GEHIP was that “the CHPS initiative was originally conceived as a community-based trial focused on identifying the best way of delivering services and sustaining community engagement for primary health care rather than a systems initiative”. Similar to developments in IR, recent approaches to HSS include participatory designs, in which "activities engage stakeholders and build relationships to ensure coproduction and ownership of HSSIs [health system strengthening interventions]" [69]. For example, Seward et al [69] outline a structured participatory process that involves mapping a patient’s journey through the health system and the associated health system bottlenecks, followed by a joint ‘Theory of Change’ workshop providing contextualised recommendations. Similarly, Kung'u et al [36] adopt a staged approach to enlisting support and participation in four African countries, analysing local contexts and jointly developing designs.

Overall, the core orientation of HSS is whole of health system, multi-level interventions to create enabling environments for change at the micro-level. HSS focuses on health system inputs and multi-stakeholder collaborative processes, engaging both a ‘demand’ (user) and ‘supply’ (system) sides of the system.

Across all three approaches (in particular the HSS studies), there was a large footprint of external donors, global health institutions, northern universities or international NGOs in intervention design and implementation.

Discussion

The review started from the premise that there are distinct schools of thought characterised as QI, IR/IS and HSS—in strengthening MNH services in LMICs, and the value of understanding the approaches in design choices. We sought to characterise these approaches and their respective assumptions of change in the published literature that self-identified with each of these approaches, as reflected in titles, abstracts and key words.

Our review discerned broad patterns associated with each approach, but also considerable fluidity and overlap between them. QI had the clearest identity and offered the most direct approach to managing change with a key focus on micro level teams. Two specific orientations were evident in the QI approach: the PDSA cycle as a structured methodology for activating facility teams and processes, and a 'standards and measurement-based’ approach. This reflects the broader debates in quality field, between assurance (measurement) and improvement (process) approaches [70].

There is growing recognition that micro-level initiatives by themselves are not sufficient and need to be combined with quality strategies and planning at multiple levels of the health system [71, 72]. As pointed out by Dixon-Woods & Martin [73], "too little has been spent on the organisational strengthening needed to make improvement.” This realisation was evident in the studies where QI interventions involved actors at meso and macro levels for support and resource mobilisation.

QI initiatives are increasingly used to improve MNH in LMICs [74,75,76,77]. While they appear technically easy and appropriate in resource constrained areas, interventions do not always embed or sustain within health systems, [77,78,79] and are constrained by a lack of political will and inadequate buy-in from leaders and resources to address problems, and the skills and time to apply QI methodologies [80, 81]. To sustain the gains from QI initiatives, greater learning from and sharing of QI implementation within and across levels, organizations, countries and regions as well as institutionalisation of quality is required [75].

The other two approaches were associated with a wide variety of interventions and pathways of change. IS/IR is a broad category [12], and even in the narrower sub-field of IS, the reported interventions solved a range of implementation problems in diverse contexts [12, 13]. Studies drew on an extensive repertoire of theory and frameworks [12,13,14], although these were applied less as theories of change than explanatory theories of factors that affected implementation outcomes [82]. The IR studies thus offered explanatory models and rigorous approaches to evaluation (effectiveness-implementation studies), and a large menu of possible interventions, but limited guidance on possible pathways or mechanisms of change [12, 31, 83, 84]. This may account for the growing popularity of QI methodologies that provide such a structured change methodology.

The HSS models recognised the need for ‘above facility’ change processes in the meso and macro levels of health systems, and tended to be holistic, embodying some degree of complexity and co-production, and were intrinsically multi-level in orientation. Applying a HSS lens on service delivery strengthening requires an understanding of the dynamic interactions between the building blocks of the health system, organisations and actors within specific contexts [32]. The multilevel orientation (actors, stakeholders, health settings) [33, 34] of HSS can strengthen the system, and foster better performance through supportive leadership, engaged teams, well supplied facilities, trained healthcare providers and supportive supervision systems [67]. However, they are less oriented to micro-level change processes.

All approaches converged on the need for multi-level, multi-component interventions, and increasingly, on locally developed, participatory and context specific designs. These are appropriate to change in complex health systems [85,86,87], evolving from linear chains of cause-and-effect, towards engaging interconnected elements holistically [88,89,90,91].

Returning to the practical problem of intervention design posed at the start of this paper, a synthesis of insights from the different approaches would recognise that there are no magic bullets [72] or single answers to strengthening MNH services in LMICs. Programmes ideally draw from different approaches and ‘logics’ in flexible ways [92], and are tailored to specific contexts. For example, a combination of facility-level PDSA cycles, participatory analyses of barriers to implementation, jointly developed theories of change, planning and resource allocation at meso level, and macro-level leadership and policy, might provide the best overall approach to strengthening MNH services. Interventions ultimately need to find resonance within local health systems and respond to a felt need to be assimilated and adopted.

Limitations

Many of the studies in this review, with important exceptions, emerged from global health institutions with an orientation towards testing the effectiveness of interventions, rather than their sustainable implementation at scale. The peer reviewed literature generally does not report on the experiential and practice knowledge of decision-makers and implementers, potentially offering different understandings of, and approaches, to MNH service delivery improvement [93]. This points to a gap in scholarship, as well as the limits of a review such as this.

We acknowledge that our search strategy and screening process, starting with an a priori hypotheses on three approaches, may have missed relevant service delivery interventions. However, it is likely that generic terms such as ‘service’ or ‘system’ would have led us to key approaches. Our screening also focused on supply side interventions focused on health care providers. While these intervention packages at times also included community-based strategies, purely demand side approaches (most notably participatory women’s groups) were beyond the scope of this review. However, these approaches have been influential globally [94], can be a trigger for quality improvement [95], and need to be considered in intervention programmes. Finally, although the review identified studies across continents, the emphasis on English-language papers may have introduced a language bias, limiting diverse perspectives. The inclusion of grey literature, even if hard to source and manage, could have allowed for a greater range of insights on service delivery improvement.

Conclusion

This review examined and compared three widely used approaches to strengthen MNH service delivery: QI, IS/IR and HSS in LMICs. As hypothesised, we were able to identify distinct targets, theories and assumptions in the three approaches while also acknowledging considerable fluidity between approaches. Programmes to improve MNH outcomes will benefit from a better appreciation of the distinctiveness and relatedness of different approaches to service delivery strengthening, how these have evolved and how they can be combined. Further exploration is needed into the practicality and effectiveness of combining these approaches in multi-level interventions.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- CHWs:

-

Community health workers

- EBP:

-

Evidence-based-practices

- HSS:

-

Health system strengthening

- IS:

-

Implementation science

- IR:

-

Implementation Research

- LMICs:

-

Low- and Middle-Income Countries

- MNH:

-

Maternal and newborn health

- NGO:

-

Non-profit organization

- PDSA:

-

Plan-do-study-act

- QI:

-

Quality improvement

- SPSS:

-

Statistical package for the social sciences

References

Girum T, Wasie A. Correlates of maternal mortality in developing countries: an ecological study in 82 countries. Matern Heal Neonatol Perinatol. 2017;3(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/S40748-017-0059-8.

Zeng W, Li G, Ahn H, et al. Cost-effectiveness of health systems strengthening interventions in improving maternal and child health in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Health Policy Plan. 2018;33(2):283–97. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czx172.

Lassi ZS, Middleton PF, Bhutta ZA, Crowther C. Strategies for improving health care seeking for maternal and newborn illnesses in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob Health Action. 2016;9(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v9.31408.

Goyet S, Broch-Alvarez V, Becker C. Quality improvement in maternal and newborn healthcare: Lessons from programmes supported by the German development organisation in Africa and Asia. BMJ Glob Heal. 2019;4(5):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001562.

Bauserman M, Thorsten VR, Nolen TL, et al. Maternal mortality in six low and lower-middle income countries from 2010 to 2018: risk factors and trends. Reprod Health. 2020;17(Suppl 3):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-020-00990-z.

Schneider H, Mukinda F, George A. District governance and improved maternal, neonatal and child health in South Africa: pathways of change. Published online 2019.

Magge H, Chilengi R, Jackson EF, et al. Tackling the hard problems: implementation experience and lessons learned in newborn health from the African Health Initiative. BMC Heal Serv Res. 2017;17(Suppl 3):829. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2659-4.

Waiswa P, O’Connell T, Bagenda D, et al. Community and District Empowerment for Scale-up (CODES): A complex district-level management intervention to improve child survival in Uganda: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2016;17(1):135. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-016-1241-4.

Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: medical research council guidance. BMJ. 2015;350:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h1258.

Laffel G, Blumenthal D. The case for using industrial quality management science in health care organizations. JAMA. 1989;262:2869–73. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1989.03430200113036.

Davidoff F, Dixon-Woods M, Leviton L, Michie S. Demystifying theory and its use in improvement. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(3):228–38. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003627.

Peters DH, Tran NT, Adam T. Implementation Research in Health: a practical guide. Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, World Health Organization. Published online 2013:66. doi:ISBN 978 92 4 150621 2

Executive Board 128th. Health System Strengthening - Current Trends and Challenges.; 2011. http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB128/B128_37-en.pdf.

Witter S, Palmer N, Balabanova D, et al. Health system strengthening — reflections on its meaning, assessment, and our state of knowledge. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2019;34:e1980–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.2882.

Moore J. The missing link: How implementation science and quality improvement can team up to improve care. Implementation in Action bulletin. Published 2019. Accessed November 10, 2020. https://quorum.hqontario.ca/en/Home/Posts/The-missing-link-How-can-implementation-science-and-quality-improvement-team-up-to-improve-care-1.

George A, Lefevre AE, Jacobs T, et al. Lenses and levels : the why, what and how of measuring health system drivers of women ’ s, children ’ s and adolescents ’ health with a governance focus. Published Online. 2019;4:143–53. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001316.

Odendaal W, Goga A, Chetty T, et al. Early reflections on mphatlalatsane, a maternal and neonatal quality improvement initiative implemented during COVID-19 in South Africa. Glob Heal Sci Pract. 2022;10(5):1–11. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-22-00022.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol Theory Pract. 2005;8(1):19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

Mianda S, Todowede OO, Schneider H. Scoping review protocol of service delivery-related interventions to improve maternal and newborn health in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Open. 2021;11(3):1–5. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042952.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850.

Macpherson P, Munthali C, Ferguson J, et al. Service delivery interventions to improve adolescents’ linkage, retention and adherence to antiretroviral therapy and HIV care. Trop Med Int Heal. 2015;20(8):1015–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/tmi.12517.

Eccles MP, Mittman BS. Welcome to implementation science. Implement Sci. 2006;1(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-1-1.

Ramaswamy R, Iracane S, Srofenyoh E, et al. Transforming maternal and neonatal outcomes in tertiary hospitals in Ghana: an integrated approach for systems change. J Obs Gynaecol Can. 2015;37(10):905–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1701-2163(16)30029-9.

Dettrick Z, Firth S, Soto EJ. Do strategies to improve quality of maternal and child health care in lower and middle income countries lead to improved outcomes? A review of the evidence. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(12):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0083070.

Ayalew F, Eyassu G, Seyoum N, et al. Using a quality improvement model to enhance providers’ performance in maternal and newborn health care: a post-only intervention and comparison design. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12884-017-1303-Y.

Bauer MS, Damschroder L, Hagedorn H, Smith J, Kilbourne AM. An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychol Published Online. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-015-0089-9.

Addie S, Olson S, Beachy SH, National Academies of Sciences E, Applying an Implementation Science Approach to Genomic Medicine (Workshop) (2015 : Washington DC. Applying an Implementation Science Approach to Genomic Medicine : Workshop Summary.

Forgaty International Centre. Overcoming Barriers to Implementation in Global Health. Toolkit Part 1: Implementation Science Methodologies and Frameworks. Published 2020. Accessed August 19, 2022. https://www.fic.nih.gov/About/center-global-health-studies/neuroscience-implementation-toolkit/Pages/methodologies-frameworks.aspx.

Moullin JC, Sabater-Hernández D, Fernandez-Llimos F, Benrimoj SI. A systematic review of implementation frameworks of innovations in healthcare and resulting generic implementation framework. Heal Res Policy Syst. 2015;13(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-015-0005-z.

Rabin BA, Brownson RC, Haire-Joshu D, Kreuter MW, Weaver NL. A glossary for dissemination and implementation research in health. J Public Heal Manag Pract. 2008;14(2):117–23. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.PHH.0000311888.06252.bb.

Jaaffar J, Low FSA. Addressing gaps for health systems strengthening: a public perspective on health systems’ response towards COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Heal. 2021;18:9047. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179047.

Witter S, Palmer N, Balabanova D, et al. Health system strengthening—reflections on its meaning, assessment, and our state of knowledge. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2019;34(4):e1980–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.2882.

Swanson RC, Bongiovanni A, Bradley E, et al. Toward a consensus on guiding principles for health systems strengthening. PLoS Med. 2010;7(12):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.

Alkenbrack S, Chaitkin M, Zeng W, Couture T, Sharma S. Did equity of reproductive and maternal health service coverage increase during the MDG era? An analysis of trends and determinants across 74 low-and middle-income countries. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0134905. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0134905.

Kung’u JK, Ndiaye B, Ndedda C, et al. Design and implementation of a health systems strengthening approach to improve health and nutrition of pregnant women and newborns in Ethiopia, Kenya, Niger, and Senegal. Matern Child Nutr. 2018;14(July 2017):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12533.

Leeman J, Rohweder C, Lee M, et al. Aligning implementation science with improvement practice: a call to action. Implement Sci Commun. 2021;2(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-021-00201-1.

Quaife M, Estafinos AS, Keraga DW, et al. Changes in health worker knowledge and motivation in the context of a quality improvement programme in Ethiopia. Heal Policyand Plan. 2021;36(August):1508–20.

Patterson J, Worku B, Jones D, Clary A, Ramaswamy R, Bose C. Ethiopian pediatric society quality improvement initiative : a pragmatic based quality approach to facility- improvement in low- resource settings. BMJ Open Qual. 2021;10:000927. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjoq-2020-000927.

Gage AD, Gotsadze T, Seid E, Mutasa R, Friedman J. Social science & medicine the influence of continuous quality Improvement on healthcare quality : a mixed-methods study from Zimbabwe. Soc Sci Med. 2020;2022(298):114831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114831.

Barker PM, Reid A, Schall MW. A framework for scaling up health interventions: lessons from large-scale improvement initiatives in Africa. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0374-x.

Sachan R, Srivastava H, Srivastava S, Behera S, Agrawal P, Gomber S. Use of point of care quality improvement methodology to improve newborn care, immediately after birth, at a tertiary care teaching hospital, in a resource constraint setting. BMJ Open Qual. 2021;10:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjoq-2021-001445.

Agarwal S, Patodia J, Mittal J, Singh Y, Agnihotri V, Sharma V. Antibiotic stewardship in a tertiary care NICU of northern India: a quality improvement initiative. BMJ Open Qual. 2021;10:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjoq-2021-001470.

Patodia J, Mittal J, Sharma V, et al. Reducing admission hypothermia in newborns at a tertiary care NICU of northern India : a quality improvement study. J Neonatal Perinatal Med. 2021;14:277–86. https://doi.org/10.3233/NPM-190385.

Yapa HM, De Neve JW, Chetty T, Herbst C, Post FA, Jiamsakul A, Geldsetzer P, Harling G, Dhlomo-Mphatswe W, Moshabela M, Matthews P, Osondu O, Tanser F, Dickman G, Herbst K, TB ̈rnighausen DP. The impact of continuous quality improvement on coverage of antenatal HIV care tests in rural South Africa : results of a. PLOS Med. 2020;17(10):1–30. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003150.

Mumtaz Z, Salway S, Nyagero J, et al. Improving the standards-based management-recognition initiative to provide high-quality, equitable maternal health services in Malawi: an implementation research protocol. BMJ Glob Heal. 2016;1(1):e000022. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2015-000022.

Necochea E, Tripathi V, Kim YM, et al. Implementation of the standards-based management and recognition approach to quality improvement in maternal, newborn, and child health programs in low-resource countries. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2015;130(S2):S17–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.04.003.

Gurung R, Jha AK, Pyakurel S, et al. Scaling up safer birth bundle through quality improvement in Nepal (SUSTAIN)—a stepped wedge cluster randomized controlled trial in public hospitals. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):65. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0917-z.

Manzi A, Nyirazinyoye L, Ntaganira J, et al. Beyond coverage: improving the quality of antenatal care delivery through integrated mentorship and quality improvement at health centers in rural Rwanda. BMC Heal Serv Res. 2018;18(1):136. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-2939-7.

Hynes M, Meehan K, Meyers J, MashukanoManeno L, Hulland E. Using a quality improvement approach to improve maternal and neonatal care in North Kivu, Democratic Republic of Congo. Reprod Heal Matters. 2017;25(51):140–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/09688080.2017.1403276.

Ashish KC, Ewald U, Basnet O, et al. Effect of a scaled-up neonatal resuscitation quality improvement package on intrapartum-related mortality in Nepal: a stepped-wedge cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2019;16(9):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002900.

Bazos DA, LaFave LR, Suresh G, Shannon KC, Nuwaha F, Splaine ME. The gas cylinder, the motorcycle and the village health team member: a proof-of-concept study for the use of the microsystems quality improvement approach to strengthen the routine immunization system in Uganda. Implement Sci. 2015;10:30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0215-3.

Doherty T, Chopra M, Nsibande D, Mngoma D. Improving the coverage of the PMTCT programme through a participatory quality improvement intervention in South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:406. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-406.

Twum-danso NAY, Akanlu GB, Osafo E, et al. A nationwide quality improvement project to accelerate Ghana ’ s progress toward millennium development goal four : design and implementation progress. Int J Qual Heal Care Adv. 2012;24(6):1–11.

Twum-Danso NAY, Dasoberi IN, Amenga-Etego IA, et al. Using quality improvement methods to test and scale up a new national policy on early post-natal care in Ghana. Health Policy Plan. 2014;29(5):622–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czt048.

Tiruneh GT, Karim AM, Avan BI, et al. The effect of implementation strength of basic emergency obstetric and newborn care (BEmONC) on facility deliveries and the met need for BEmONC at the primary health care level in Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):123. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1751-z.

Bergh AM, de Graft-Johnson J, Khadka N, et al. The three waves in implementation of facility-based kangaroo mother care: a multi-country case study from Asia. BMC Int Heal Hum Rights. 2016;16:4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-016-0080-4.

Yue J, Liu J, Zhao Y, et al. Evaluating factors that influenced the successful implementation of an evidence-based neonatal care intervention in Chinese hospitals using the PARIHS framework. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-07493-6.

Maru S, Nirola I, Thapa A, et al. An integrated community health worker intervention in rural Nepal: a type 2 hybrid effectiveness-implementation study protocol. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-018-0741-x.

Mohammadi M, Bergh AM, Heidarzadeh M, et al. Implementation and effectiveness of continuous kangaroo mother care: a participatory action research protocol. Int Breastfeed J. 2021;16(1):24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-021-00367-3.

Bohren MA, Lorencatto F, Coomarasamy A, et al. Formative research to design an implementation strategy for a postpartum hemorrhage initial response treatment bundle (E-MOTIVE): study protocol. Reprod Health. 2021;18(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01162-3.

Finocchario-Kessler S, Odera I, Okoth V, et al. Lessons learned from implementing the HIV infant tracking system (HITSystem): a web-based intervention to improve early infant diagnosis in Kenya. Heal. 2015;3(4):190–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hjdsi.2015.07.004.

Orangi S, Kairu A, Ondera J, et al. Examining the implementation of the Linda Mama free maternity program in Kenya. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2021;36(6):2277–96. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.3298.

Harsha Bangura A, Nirola I, Thapa P, et al. Measuring fidelity, feasibility, costs: an implementation evaluation of a cluster-controlled trial of group antenatal care in rural Nepal. Reprod Heal. 2020;17(1):5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-019-0840-4.

Cole CB, Pacca J, Mehl A, et al. Toward communities as systems: a sequential mixed methods study to understand factors enabling implementation of a skilled birth attendance intervention in Nampula Province, Mozambique. Reprod Heal. 2018;15(1):132. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-018-0574-8.

Shakarishvili G, Lansang MA, Mitta V, et al. Health systems strengthening: a common classification and framework for investment analysis. Health Policy Plan. 2011;26(4):316–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czq053.

Sensalire S, Isabirye P, Karamagi E, Byabagambi J, Rahimzai M, Calnan J. Saving mothers, giving life approach for strengthening health systems to reduce maternal and newborn deaths in 7 scale-up districts in northern Uganda. Glob Heal Sci Pract. 2013;2019(7):S168–87. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-18-00263.

Awoonor-Williams JK, Bawah AA, Nyonator FK, et al. The Ghana essential health interventions program: a plausibility trial of the impact of health systems strengthening on maternal & child survival. BMC Heal Serv Res. 2013;13(Suppl 2):S3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-s2-s3.

Seward N, Hanlon C, Abdella A, et al. HeAlth System StrEngThening in four sub-Saharan African countries (ASSET) to achieve high-quality, evidence-informed surgical, maternal and newborn, and primary care: protocol for pre-implementation phase studies. Glob Health Action. 2022;15(1):1987044. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2021.1987044.

World Health Organization. Handbook for National Quality Policy and Strategy.; 2018. http://www.who.int/servicedeliverysafety/areas/qhc/nqps_handbook/en/; http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272357/9789241565561-eng.pdf?ua=1.

Reed JE, Card AJ. The problem with plan-do-study-act cycles. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(3):147–52. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-005076.

Rand A, Dixon-Woods M, Martin GP. Does quality improvement improve quality? Futur Hosp J. 2016;3(3):191–5.

Dixon-Woods M, McNicol S, Martin G. Overcoming Challenges to Improving Quality Lessons from the Health Foundation’s Improvement Programme Evaluations and Relevant Literature Identify Innovate Demonstrate Encourage.; 2012. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000760

Kringos DS, Sunol R, Wagner C, et al. The influence of context on the effectiveness of hospital quality improvement strategies: a review of systematic reviews quality, performance, safety and outcomes. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):1–3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0906-0.

Heiby JR. The use of modern quality improvement approaches to strengthen African health systems: a 5-year agenda. Int J Qual Heal Care. 2013;26:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/3.3.147.

Manzi F, Marchant T, Hanson C, et al. Harnessing the health systems strengthening potential of quality improvement using realist evaluation: an example from southern Tanzania. Health Policy Plan. 2020;35:II9–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/HEAPOL/CZAA128.

Wells S, Tamir O, Gray J, Naidoo D, Bekhit M, Goldmann D. Are quality improvement collaboratives effective? A systematic review Bmj Qual Saf. 2018;27:226–40.

Hulscher M, Schouten L, Grol R, Buchan H. Determinants of suc- cess of quality improvement collaboratives: what does the literature show? BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22:19–31.

Nadeem E, Olin S, Hill L, Hoagwood K, Horwitz S. Understanding the components of quality improvement collaboratives: a systematic literature review. Milbank Q. 2013;91:354–94.

Ingabire W, Reine PM, Hedt-Gauthier BL, et al. Roadmap to an effective quality improvement and patient safety program implementation in a rural hospital setting. Healthcare. 2015;3(4):277–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hjdsi.2015.10.010.

Wagenaar BH, Hirschhorn LR, Henley C, et al. Data-driven quality improvement in low-and middle-income country health systems: Lessons from seven years of implementation experience across Mozambique, Rwanda, and Zambia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(Suppl 3):65–75. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2661-x.

Damschroder LJ. Clarity out of chaos: Use of theory in implementation research. Psychiatry Res. 2020;283(April 2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.06.036

Papoutsi C, Boaden R, Foy R GJ. Challenges for implementation science. In: Raine R, Fitzpatrick R, Barratt H, ed. Challenges, Solutions and Future Directions in the Evaluation of Service Innovations in Health Care and Public Health. 4th ed. HR Journals Library; 2016:121–132.

Binagwaho A, Frisch MF, Udoh K, et al. Implementation research: an efficient and effective tool to accelerate universal health coverage. Int J Heal Policy Manag. 2020;9(5):182–4. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2019.125.

Hirschhorn LR, Baynes C, Sherr K, et al. Approaches to ensuring and improving quality in the context of health system strengthening: a cross-site analysis of the five African health initiative partnership programs. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(SUPPL.2):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-S2-S8.

Koczwara B, Stover AM, Davies L, et al. Harnessing the synergy between improvement science and implementation science in cancer: a call to action. J Oncol Pract. 2020;14(6):335–40. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.17.00083.

Klein WMP. Conducting multilevel intervention research : leveraging and looking beyond methodological advances. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2012;44:10–1. https://doi.org/10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs016.

Braithwaite J, Churruca K, Long JC, Ellis LA, Herkes J. When complexity science meets implementation science : a theoretical and empirical analysis of systems change. Published Online. 2018;16:1–14.

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Mitchie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical research council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337(7676):979–83. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a1655.

Bullock A, Morris ZS, Atwell C. Collaboration between health services managers and researchers: making a difference? J Heal Serv Res Policy. 2012;17(SUPPL. 2):2–10. https://doi.org/10.1258/jhsrp.2011.011099.

Cleary PD, Gross CP, Zaslavsky AM, Taplin SH. Multilevel interventions : study design and analysis issues. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2012;15:49–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs010.

Greenhalgh T, Papoutsi C. Spreading and scaling up innovation and improvement. BMJ. 2019;365(May):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l2068.

Ramani S, Whyle EB, Kagwanja N. What research evidence can support the decolonisation of global health? Making space for deeper scholarship in global health journals. Lancet Glob Heal. 2023;11(9):e1464–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(23)00299-1.

Prost A, Colbourn T, Seward N, et al. Women’s groups practising participatory learning and action to improve maternal and newborn health in low-resource settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;381(9879):1736–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60685-6.

Preston R, Rannard S, Felton-Busch C, et al. How and why do participatory women’s groups (PWGs) improve the quality of maternal and child health (MCH) care? A systematic review protocol. BMJ Open. 2019;9(9):e030461. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030461.

Olaniran AA, Oludipe M, Hill Z, et al. From theory to implementation: adaptations to a quality improvement initiative according to implementation context. Qual Health Res. 2022;32(4):646–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/10497323211058699.

Funding

This work is based on the research supported by the South African Research Chairs Initiative of the Department of Science and Technology and National Research Foundation of South Africa (grant no. 98918), and ELMA philanthropies through the South African Medical Research Council.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HS conceptualized the review. SM and OT were responsible for designing the review methods, including the search strategies, and retrieved screened articles. HS analyzed the quantitative data and SM and HS conducted the qualitative review. SM and HS drafted the manuscript, and OTT provided editorial comments on the drafts and read and approved the final manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Supplementary Table 1. Search String strategy [Pilot sample in PubMed]. Supplementary Figure 1. Terms appearing in title or keywords or abstracts (n=231). Supplementary Figure 2. Percent of publications where terms appear at least once (n=231). Supplementary Figure 3. Distribution of journals publishing archetypes, showing archetype distribution (n=55) (blue = QI; orange = IR; grey = HSS). Supplementary Figure 4. Distribution of archetypes over time (n=55).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Mianda, S., Todowede, O. & Schneider, H. Service delivery interventions to improve maternal and newborn health in low- and middle-income countries: scoping review of quality improvement, implementation research and health system strengthening approaches. BMC Health Serv Res 23, 1223 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-10202-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-10202-6