Abstract

Background

Clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) provide recommendations for practice, but the proliferation of CPGs issued by multiple organisations in recent years has raised concern about their quality. The aim of this study was to systematically appraise CPGs quality for low back pain (LBP) interventions and to explore inter-rater reliability (IRR) between quality appraisers. The time between systematic review search and publication of CPGs was recorded.

Methods

Electronic databases (PubMed, Embase, PEDro, TRIP), guideline organisation databases, websites, and grey literature were searched from January 2016 to January 2020 to identify GPCs on rehabilitative, pharmacological or surgical intervention for LBP management. Four independent reviewers used the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II) tool to evaluate CPGs quality and record the year the CPGs were published and the year the search strategies were conducted.

Results

A total of 21 CPGs met the inclusion criteria and were appraised. Seven (33%) were broad in scope and involved surgery, rehabilitation or pharmacological intervention. The score for each AGREE II item was: Editorial Independence (median 67%, interquartile range [IQR] 31–84%), Scope and Purpose (median 64%, IQR 22–83%), Rigour of Development (median 50%, IQR 21–72%), Clarity and Presentation (median 50%, IQR 28–79%), Stakeholder Involvement (median 36%, IQR 10–74%), and Applicability (median 11%, IQR 0–46%). The IRR between the assessors was nearly perfect (interclass correlation 0.90; 95% confidence interval 0.88–0.91). The median time span was 2 years (range, 1–4), however, 38% of the CPGs did not report the coverage dates for systematic searches.

Conclusions

We found methodological limitations that affect CPGs quality. In our opinion, a universal database is needed in which guidelines can be registered and recommendations dynamically developed through a living systematic reviews approach to ensure that guidelines are based on updated evidence.

Level of evidence

1

Trial registration

REGISTRATION PROSPERO DETAILS: CRD42019127619.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The worldwide point prevalence of Low Back Pain (LBP) is 9.4% (95% CI, 9.0–9.8) in 2010 [1]. Next to the common cold, it is one of the commonest reasons why people seek their physician, with a substantial medical social and economic impact for individuals, families, and society due to its high direct and indirect costs [2,3,4]. Back pain is a leading cause of years lived with disability and the first cause of activity limitation and absence from work [1]. The overall burden of LBP arising from ergonomic exposures at work was estimated at 21.8 million [95% Confidence Interval (CI) 14.5–30.5] disability adjusted life years (DALYs) in 2010 [5]. In response to the global burden, numerous CPGs have been issued by medical societies and working groups, providing recommendations for its diagnosis and management [6, 7]. While the principles for developing CPGs are well established, their proliferation has raised concern about quality. Published CPGs appraisals report that the quality is generally poor, though it appears to have recently improved, and that their applicability is generally low [8, 9]. Appraisals of CPGs for LBP [9,10,11,12,13,14] do not take into account the most recently published guidelines. Since CPGs provide a bridge between scientific literature and clinical decision making, their implementation in clinical practice should be based on recent evidence, and consider as much as possible a wide range of therapeutic choices [15].

But because 1 out of 5 recommendations in clinical guidelines go out of date within 3 years, the validity of recommendations beyond 3 years is potentially questionable [16]. As a general rule, CPGs should be reviewed every 3 years after their issue [17]. The National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE), the benchmark in guidelines production, has stated that “A formal review of the need to update a guideline is usually undertaken by NICE 3 years after its publication” [18]. This is warranted by the time span between the year of running the systematic search strategy during guideline production and the year of publication in a systematic review [19]. This time span is further stretched because guidelines production and dissemination need to be based on systematic reviews. The use of guidelines older than 3 years would be considered unethical in clinical decision making and mistaken in identifying high quality guidelines with not the most recent-update, available and reliable evidence [16, 17, 20].

Moreover, existing appraisals of guidelines for LBP do not rely on a comprehensive search of the many possible therapeutic options (rehabilitative, pharmacological or surgical) for treating acute and chronic LBP [21]. The scope is an important item in the AGREE II favoring guidelines that are broad in scope rather than those focusing on a particular set of interventions for a specific condition [22].

With this study, we critically appraised only the most recent evidence-based CPGs for LBP interventions by means of the AGREE (Appraisal of Guidelines Research and Evaluation) II instrument, the gold standard for critical appraisal of guidelines [22, 23], consistent with the assumption that time can influence CPG reliability. Also, we evaluated the inter-rater reliability of AGREE II and recorded the time span as the years between the date of last search and period covered by the search and guideline publication date.

Methods

The reporting of this systematic review fulfils the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses [24, 25]. No ethics committee approval was needed. The protocol is registered in PROSPERO (CRD42019127619).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

In line with the World Health Organization, we defined a CPG as a document containing “systematically developed evidence-based statements that assist providers, patients, policy makers and other stakeholders to make informed decisions on health care and public health policy” [26].

Inclusion criteria were: (i) the systematic process evaluated the recommendations; (ii) the CPG was focused on rehabilitation, pharmacological or surgical therapeutic intervention for LBP management; (iii) the full text was published in the last 4 years (2016–2020). We used the most up-to-date version and its supplementary documents. No language restrictions were applied. Exclusion criteria were: (i) not primarily focused on LBP, such as national/international guidelines in which LBP was briefly mentioned in the context of a more comprehensive disease evaluation; (ii) not issued by a national or international society (e.g., designed for local use); (iii) declaration of recommendations was based exclusively on consensus statements or systematic reviews or commentary editorials related to published CPGs; (iv) focus on interventions other than therapeutic (e.g., prevention, diagnosis); (v) based on population subgroups (e.g., pregnant women), specific causes (e.g. spondyloarthritis) or mixed/generic population (e.g., musculoskeletal chronic pain).

Information sources and search strategy

We systematically searched the PubMed, Embase, PEDro, and TRIP databases using the adapted terms and keywords derived from the scoping search outlined in the search strategy. We checked guideline organisation databases (e.g., National Institute for Clinical Excellence) and guideline websites (e.g., eGuidelines). Supplementary Digital Content 1 illustrates the search strategy. Two reviewers (SG, GC) with a solid background in clinical epidemiology ran the search strategy in March 2019 and updated the results in January 2020. Grey literature was searched using Google Scholar and reference lists were screened for further eligible CPGs.

Selection of clinical practice guidelines

Search results were uploaded to Endnote software and duplicates were removed [27, 28]. Two independent reviewers (SG, VI) screened the titles and abstracts according to the eligibility criteria. Full texts were retrieved when abstracts gave insufficient information or in case of disagreement between the two reviewers. When disagreement persisted, a third reviewer was consulted (GC). Rayyan software (https://rayyan.qcri.org/) was used to manage screening and selection [29]. Reasons for study exclusion are reported.

Appraisal of clinical practice guidelines

Four independent researchers (MB, GC, SG, VI) appraised each CPG using the AGREE II instrument and recorded with a self-chronometer the time taken for each assessment. The researchers received training in the use of AGREE II. They completed the AGREE II Online Training Tool (http://www.agreetrust.org/resource-centre/agree-ii-training-tools/) and participated in two calibration rounds with a sample of four relevant CPGs of varying quality from a previous overview of clinical guidelines for chronic LBP restricted to 2012 [30]. The original AGREE tool was published in 2003 has since then been revised in an updated version. The AGREE II instrument [22] consists of 23 items organized into six quality domains: scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigour of development, clarity of presentation, applicability, and editorial independence. Supplementary Digital Content 2 shown the items and domains of the AGREE II instrument [31]. Answers to items are graded on a 7-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). A standardized score (range, 0 to 100%) was calculated for each domain.

The appraisers completed the first global rating item on a 7-point scale (1 = lowest possible quality, 7 = highest possible quality) and the second global rating item of recommending the guidelines for use in practice, with one of three options (Yes, Yes, with modifications, and No). One author (VI) calculated the standardised domain score for each of the six domains as recommended by AGREE II [22, 32]. The general data from each CPG were collected: i) authors and year of publication; ii) ex novo, update or adoption/adolopment CPG status; iii) continent of origin; iv) organization/society/association, funding source, conflict of interest. We also extracted content information such as target population, target interventions (i.e., surgery, physical therapy, pharmaceutics, educational / behavioural, alternative medicine), rating methods for the quality of evidence (e.g., the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation - GRADE), presence of a multidisciplinary panel (as defined by AGREE II: potential candidates for a panel group include clinicians, content experts, researchers, policy makers, clinical administrators, and funders; at least one methodology expert), and patient involvement (as defined by AGREE II: to capture patient/public views and preferences). Supplementary Digital Content 2.

Data synthesis

We used descriptive statistics to summarize the characteristics of CPGs deemed eligible for inclusion. Data are summarized as frequency number (percentage) or median and interquartile range (IQR). We calculated a quality score for each of the six domains of CPGs using the formula presented in the AGREE II User’s Manual [32]. The appraisers added notes and completed the two global rating items at the end of each AGREE II assessment. The first global rating item asks appraisers to rate the overall quality of the guideline on a 7-point scale (1 = lowest possible quality and 7 = highest possible quality). Domain scores are calculated by summing up the appraisers’ scores of the individual items in a domain and then scaling the total as a percentage of the maximum possible score for that domain, which is then automatically generated on the platform My AGREE PLUS [33].

The second global rating item asks whether the appraiser would recommend the guideline for use in practice and to respond with one of three options (Yes, Yes, with modifications, and No).

The first global rating was adopted to formulate the agreement on the overall assessment between the four appraisers measuring the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) with 95% confidence interval (CI). The degree of agreement was graded according to Landis and Koch [34]: slight (0.01–0.2); fair (0.21–0.4); moderate (0.41–0.6); substantial (0.61–0.8); and almost perfect (0.81–1). Statistical significance was a P value < 0.05. All tests were two-sided [34]. All data analyses were performed using STATA (StataCorp. 2017. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX, USA: StataCorp LLC).

Results

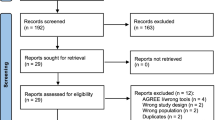

Search results

The systematic search retrieved 2502 citations; additional 30 citations were retrieved from the grey literature. A total of 70 CPGs and related documents underwent full-text screening, 25 of which met the inclusion criteria. Four are awaiting assessment (Fig. 1). Finally, we appraised 21 CPGs using AGREE II (Supplementary Digital Content 1 and 3).

Characteristics of CPGs

Table 1 presents the main characteristics of the 21 CPGs: 10 (47.6%) addressed multiple interventions. Rating of evidence quality was planned in 76% of the guidelines and reported in 67%. More than half (52%) had a multidisciplinary panel and less than half (38%) reported patient involvement (Supplementary Digital Content 3).

AGREE II domains assessment

Overall, the highest rating AGREE II domain was Editorial Independence (median 67%, interquartile range [IQR] 31–84%), followed by Scope and Purpose (median 64%, IQR 22–83%), Rigour of Development (median 50%, IQR 21–72%), Clarity and Presentation (median 50%, IQR 28–79%), Stakeholder Involvement (median 36.1%, IQR 10–74%), and Applicability (median 11%, IQR 0–46%). In the overall guideline assessment, the median of the overall quality item was 42% (IQR 15–67%) and the most frequent recommendation regarding the use of the guideline was “No” (Table 2).

The NICE guideline [51] had the highest quality (96%) in the area of Educational/behavioural, physical therapy, pharmaceutical interventions. The Belgian Healthcare Knowledge Centre (KCE) (83%) guideline [56] had high quality and covered the same interventions plus surgery with a short time span (1 and 2 years, respectively) for searching evidence (Supplementary Digital Content 3).

Inter-rater reliability and time for AGREE II appraisal

Inter-rater agreement was nearly perfect (ICC 0.90; 95% CI 0.88–0.91). Guidelines appraisal took 42 min on average to complete (95% CI 35–50).

Time to publication

Overall, 38.1% of the CPGs did not report the dates of systematic search strategy, whereas less than half (47.6%) reported a median of 2 years (IQR 1–4) from search to publication. Only half provided a search within 1 year after publication (Table 1).

Discussion

Here we report the results of quality appraisal using AGREE II of the most recent CPGs for LBP interventions (published January 2016 to January 2020) that we retrieved by systematic search of electronic medical databases and guidelines websites. A key finding was the variability in the quality of the CPGs across all six AGREE II domains; the highest average scores (> 60%) were recorded for Domain 6 - Editorial Independence and the Domain 1 - Scope and Purpose and the lowest (< 15%) for Domain 5 - Applicability. The overall quality was rated low and the most frequent response for guideline recommendation was “No” (15 out of 21 CPGs).

Our findings are shared by previous appraisals of CPGs for rehabilitation [57] and other contexts [8, 58, 59] that suggest room for improvement regarding rigour of development, stakeholder involvement, and applicability [8, 58, 59]. While only half of the CPGs were noted to have acceptable rigour of development (Domain 3 - Rigour of Development), the variability in this domain was considerable. A low score for this domain is worrying, as it has been identified as a strong predictor of quality by the AGREE instrument [8]. Regression analysis showed a statistically significant influence of the assessment of the items in this domain on overall guideline quality [60]. The item assessing the systematic search can have great importance (i.e., “Item 7: Systematic methods were used to search for evidence”) because CPGs ought to be based on recently updated evidence. However, we found that less than half did not report the time coverage of systematic search and, when reported, it ranged from 1 to 4 years before publication. Two-thirds of the CPGs in our sample adequately planned and judged the body of the evidence linked to recommendations (e.g., GRADE). However, because the application of a system for grading the evidence (i.e., GRADE) cannot always ensure inclusion of the most updated evidence within an acceptable time span, reliability should be evaluated with caution.

The validity of each recommendation, and of the CPG, is determined by the methodological quality and the transparency of its development and by the “living evidence” on which it is based. As suggested by Garcia et al., waiting more than 3 years to review a guideline is potentially too long, in which case the recommendations may be outdated by the time of guideline publication [16]. This critical issue has been addressed by the living CPGs concept [61], which draws inspiration from the established model of living systematic reviews, where evidence is continuously updated and incorporated as soon as available in the literature through a process of continuous surveillance [62]. Accordingly, AGREE II should place importance on timing and rate CPG a high-quality score when the search is conducted within 2 years of completion of the review [63].

Less than one third of the CPGs in this sample met the AGREE II criterion for participation of patients and their advocate (Domain 2 - Stakeholder Involvement). Guideline developers need to prioritize patient and stakeholder involvement starting from the early stages of CPG development. They should be actively involved as members on guideline panels and their comments and inputs included in the draft guideline [64]. Furthermore, evidence suggests that involvement of patients and stakeholders leads to the inclusion of patient-relevant topics and enhances CPG implementation [65]. Unfortunately, development and implementation are erroneously considered as separate activities [8]. In our appraisal, the poorest score was recorded for CPGs applicability (Domain 5 - Applicability), with results similar to other CPGs in rehabilitation [57] and other conditions [8, 12, 66,67,68]. CPGs can provide healthcare professionals with the necessary guidance to access the best research evidence efficiently. Nonetheless, they have little effect on changing clinical behavior.

Only half of the CPGs in our sample were rated satisfactory for adequacy of the reporting of recommendations and options for management (Domain 4 - Clarity of Presentation). This may be related to the purpose of AGREE II: the current version makes no distinction between quality of reporting and quality of conduct of a CPG. Despite good reporting, the methodological conduct underlying a guideline can still be weak [69]. Quality of conduct and reporting should be judged separately, just as for all other study designs [70, 71]. In systematic reviews, for instance, PRISMA and the AMSTAR assess the quality of reporting and the quality of conduct, respectively [72].

We recorded high compliance of the CPGs with the overall aim of the guideline, the clinical question, and the target population (Domain 1 - Scope and Purpose). This could be explained by the focus on LBP, which is the most prevalent musculoskeletal condition for which guidelines are needed in view of the years lived with disability in most countries [73]. Lastly, we recorded high compliance of the CPGs with the reporting of sources of support (Domain 6 - Editorial Independence). Given the global socioeconomic burden of LBP and the need for care, CPGs must report the presence and management of conflict of interests.

Strengths and limitations

Our appraisal has several strengths. We performed an exhaustive search that included explicit eligibility criteria and independent duplicate assessment of eligibility. Four reviewers were involved in the appraisal, with a nearly perfect inter-rater reliability. While all appraisers were trained in the use of AGREE II, it should be acknowledged that the appraisers shared a similar background (methodology and rehabilitation), which may partially explain the high overall agreement. Indeed, our team included clinical experts and methodologists with experience in clinical epidemiology, including systematic reviews and CPGs. Even after receiving the same training however, guideline appraisers from different areas may still interpret the items and the scoring system differently [74]. Furthermore, it is possible that the appraisers, basing the assessment on their own experience, paid more attention to assessing the quality of reporting than the quality of conduct and vice versa. We analysed a reliable subset of CPGs restricted to LBP in order to ensure consistency of appraisal, while avoiding discrepancies in item judgement due to different clinical contexts (e.g., AGREE II to assess CPGs in oncology differs from orthopaedics). We focused on the most recent guideline versions in order to offer stakeholders, policy makers, clinicians, and patients the latest evidence for the effectives of interventions. However, selecting the CPGs was a challenge, since the definition of guidelines is not universally established and the meaning of consensus and that of evidence-based CPG are sometimes confused. The rigour of methods and panel of experts have to be simultaneously considered in a CPG, but the current definition does not explicate these elements.

A possible limitation of our work is linked to characteristics of the AGREE II itself. It focuses on the quality of the development of CPGs, but this is not sufficient to ensure implementation of single clinical recommendations and improvement in health outcomes [75]. While high-quality CPGs can guarantee rigour in the production of recommendations, their implementation depends largely on how health care professionals decide whether or not to implement a single recommendation in the balance between content (strength and direction of a recommendation), clinical expertise, patients’ values and resources available. The implementation of a single clinical recommendation cannot be disjointed from overall CPG quality.

Future spin for research

At the time of its publication, a CPG can already be outdated and so will not reflect the most recent evidence. Indeed, time can influence its reliability: (a) during the conduction of systematic reviews for the production of the body of the evidence needed during CPG development; (b) between finalization of a CPG and its publication. In order to avoid waste of effort and of resources due to duplication of CPGs or CPGs outdated before their time, we urge for the creation of a universal database in which guidelines can be registered and updated along the lines of registers for RCTs (e.g., WHO or clincialtrials.gov) and systematic reviews (e.g., PROSPERO) but for CPGs. In this way, a “living and dynamic” development of recommendations can be better recognized by identifying the most recent literature [76].

Conclusion

We found methodological limitations affecting CPG quality. Our work highlights the importance of adoption of high quality and updated CPGs to guarantee the validity of a single recommendations, notwithstanding the possibility that implementation of each single recommendation may be the result of a balanced decision between content (strength and direction of a recommendation), clinical expertise, and available resources. We call for a universal database in which guidelines can be registered and recommendations dynamically developed through a living systematic reviews approach to ensure that CPGs are based on recent evidence.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article with all additional materials. Row data are stored at the following link: https://osf.io/xwbu2/?view_only=d3aa81b467874b468bd1207d96df7376

Abbreviations

- ACP:

-

American College of Physicians

- AGREE II:

-

Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II

- AIM:

-

American Imaging Management Specialty Health

- AMSTAR:

-

A Measurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews

- AOA:

-

American Osteopathic Association

- ASIPP:

-

American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians

- BMA:

-

Brazilian Medical Association

- CCGI:

-

Canadian Chiropractic Guideline Initiative

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- CPGs:

-

Clinical Practice Guidelines

- KCE:

-

Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre

- CPLA:

-

Change Pain Latin America

- CCGPP:

-

Council on Chiropractic Guidelines and Practice Parameters

- CAAM:

-

China Association of Acupuncture-Moxibustion

- DALYs:

-

Disability Adjusted Life Years

- DSA:

-

Dutch Society of Anesthesiologists

- GSCI:

-

Global Spine Care Initiative

- GRADE:

-

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- IQR:

-

Interquartile Range

- ICC:

-

Intraclass correlation

- ICSI:

-

Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement

- KIOM:

-

Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine

- KSSS:

-

Korean Society of Spine Surgery

- L&I:

-

Labor & Industries

- LBP:

-

Low Back Pain

- NICE:

-

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- PEDro:

-

Physiotherapy Evidence Database

- PSP:

-

Polish Society of Physiotherapy

- PSSS:

-

Polish Spine Surgery Society

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Intervention for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

- TOP:

-

Toward Optimized Practice Low Back Pain Working Group

- TRIP:

-

Turning Research into Practice

- VADoD:

-

Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense Collaboration Office

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Hoy D, March L, Brooks P, Blyth F, Woolf A, Bain C, et al. The global burden of low back pain: estimates from the global burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(6):968–74.

Vrbanic TS. Low back pain--from definition to diagnosis. Reumatizam. 2011;58(2):105–7.

Deyo RA, Phillips WR. Low back pain. A primary care challenge. Spine. 1996;21(24):2826–32.

Childs JD, Fritz JM, Flynn TW, Irrgang JJ, Johnson KK, Majkowski GR, et al. A clinical prediction rule to identify patients with low back pain most likely to benefit from spinal manipulation: a validation study. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(12):920–8.

Hoy D, March L, Brooks P, Woolf A, Blyth F, Vos T, et al. Measuring the global burden of low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2010;24(2):155–65.

O’Connell NE, Cook CE, Wand BM, Ward SP. Clinical guidelines for low back pain: a critical review of consensus and inconsistencies across three major guidelines. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2016;30(6):968–80.

O'Sullivan K, O'Keeffe M, O'Sullivan P. NICE low back pain guidelines: opportunities and obstacles to change practice. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(22):1632–3.

Alonso-Coello P, Irfan A, Sola I, Gich I, Delgado-Noguera M, Rigau D, et al. The quality of clinical practice guidelines over the last two decades: a systematic review of guideline appraisal studies. Qual Safety Health Care. 2010;19(6):e58.

Meroni R, Piscitelli D, Ravasio C, Vanti C, Bertozzi L, De Vito G, et al. Evidence for managing chronic low back pain in primary care: a review of recommendations from high-quality clinical practice guidelines. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;1:1–15.

van Tulder MW, Tuut M, Pennick V, Bombardier C, Assendelft WJ. Quality of primary care guidelines for acute low back pain. Spine. 2004;29(17):E357–62.

Bouwmeester W, van Enst A, van Tulder M. Quality of low back pain guidelines improved. Spine. 2009;34(23):2562–7.

Doniselli FM, Zanardo M, Manfre L, Papini GDE, Rovira A, Sardanelli F, et al. A critical appraisal of the quality of low back pain practice guidelines using the AGREE II tool and comparison with previous evaluations: a EuroAIM initiative. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(11):2781–90.

Dagenais S, Tricco AC, Haldeman S. Synthesis of recommendations for the assessment and management of low back pain from recent clinical practice guidelines. Spine J. 2010;10(6):514–29.

Ng JY, Mohiuddin U. Quality of complementary and alternative medicine recommendations in low back pain guidelines: a systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2020;29(8):1833–44.

Gurgel RK. Updating clinical practice guidelines: how do we stay current? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;153(4):488–90.

Martinez Garcia L, Sanabria AJ, Garcia Alvarez E, Trujillo-Martin MM, Etxeandia-Ikobaltzeta I, Kotzeva A, et al. The validity of recommendations from clinical guidelines: a survival analysis. CMAJ. 2014;186(16):1211–9.

Shekelle PG, Ortiz E, Rhodes S, Morton SC, Eccles MP, Grimshaw JM, et al. Validity of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality clinical practice guidelines: how quickly do guidelines become outdated? JAMA. 2001;286(12):1461–7.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Developing NICE guidelines: the manual. Process and methods, published: 31 October 2014, niceorguk/process/pmg20©; 2014.

Yoshii A, Plaut DA, McGraw KA, Anderson MJ, Wellik KE. Analysis of the reporting of search strategies in Cochrane systematic reviews. J Med Libr Assoc. 2009;97(1):21–9.

Pieper D, Antoine S-L, Neugebauer EAM, Eikermann M. Up-to-dateness of reviews is often neglected in overviews: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(12):1302–8.

Wong JJ, Cote P, Sutton DA, Randhawa K, Yu H, Varatharajan S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the noninvasive management of low back pain: a systematic review by the Ontario protocol for traffic Injury management (OPTIMa) collaboration. Eur J Pain. 2017;21(2):201–16.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010;182(18):E839–42.

Brouwers MC, Kerkvliet K, Spithoff K, Consortium ANS. The AGREE reporting checklist: a tool to improve reporting of clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016;352:i1152.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Open Med. 2009;3(3):e123–30.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700.

Wolrd Health Organization. WHO handbook for guideline development. 2nd ed: World Health Organizationhttp://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/145714; 2014.

Eapen BR. EndNote 7.0. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72(2):165–6.

Bramer WM, Milic J, Mast F. Reviewing retrieved references for inclusion in systematic reviews using EndNote. J Med Libr Assoc. 2017;105(1):84–7.

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210.

Pillastrini P, Gardenghi I, Bonetti F, Capra F, Guccione A, Mugnai R, et al. An updated overview of clinical guidelines for chronic low back pain management in primary care. Joint Bone Spine. 2012;79(2):176–85.

Appraisal of guidelines for research and evaluation II: AGREE II instrument [http://www.agreetrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/AGREE-II-Users-Manual-and-23-item-Instrument_2009_UPDATE_2013.pdf].

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. Development of the AGREE II, part 2: assessment of validity of items and tools to support application. CMAJ. 2010;182(10):E472–8.

Makarski J, Brouwers MC, Enterprise A. The AGREE Enterprise: a decade of advancing clinical practice guidelines. Implement Sci. 2014;9:103.

Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–74.

Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA. Clinical guidelines Committee of the American College of P. noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low Back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(7):514–30.

AIM. AIM Specialty Health - Musculoskeletal Program - Clinical Appropriateness Guidelines for Spine Surgery. https://aimspecialtyhealthcom/guidelines/PDFs/2019/May18/AIM_Guidelines_MSK_Spine-Surgerypdf.

Task Force on the Low Back Pain Clinical Practice G. American Osteopathic Association guidelines for osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT) for patients with low Back pain. J Am Osteopathic Assoc. 2016;116(8):536–49.

Navani A, Manchikanti L, Albers SL, Latchaw RE, Sanapati J, Kaye AD, et al. Responsible, safe, and effective use of biologics in the Management of low Back Pain: American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) guidelines. Pain Phys. 2019;22(1S):S1–S74.

Brazilian Medical A, Silvinato A, Simoes RS, Buzzini RF, Bernardo WM. Lumbar herniated disc treatment with percutaneous hydrodiscectomy. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2018;64(9):778–82.

Zhao H, Liu B, Liu Z, Xie L, Fang Y, Zhu Y, et al. Clinical practice guidelines of using acupuncture for low back pain. World J Acupuncture - Moxibustion. 2016;26(4):1–13 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1003525717300168.

Bussieres AE, Stewart G, Al-Zoubi F, Decina P, Descarreaux M, Haskett D, et al. Spinal manipulative therapy and other conservative treatments for low Back pain: a guideline from the Canadian chiropractic guideline initiative. J Manip Physiol Ther. 2018;41(4):265–93.

Globe G, Farabaugh RJ, Hawk C, Morris CE, Baker G, Whalen WM, et al. Clinical practice guideline: chiropractic Care for low Back Pain. J Manip Physiol Ther. 2016;39(1):1–22.

Amescua-Garcia C, Colimon F, Guerrero C, Jreige Iskandar A, Berenguel Cook M, Bonilla P, et al. Most relevant neuropathic pain treatment and chronic low Back pain management guidelines: a change pain Latin America advisory panel consensus. Pain Med. 2018;19(3):460–70.

Itz CJ, Willems PC, Zeilstra DJ, Huygen FJ. Dutch society of a, Dutch orthopedic a, et al. Dutch multidisciplinary guideline for invasive treatment of pain syndromes of the lumbosacral spine. Pain Pract. 2016;16(1):90–110.

Acaroglu E, Nordin M, Randhawa K, Chou R, Cote P, Mmopelwa T, et al. The global spine care initiative: a summary of guidelines on invasive interventions for the management of persistent and disabling spinal pain in low- and middle-income communities. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(Suppl 6):870–8.

Thorson D, Campbell R, Massey M, Mueller B, McCathie B, Richards H, et al. Low Back pain, adult acute and subacute. 16th ed; 2018. Available from: https://www.icsi.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/March-2018-LBP-Interactive.pdf.

Van Wambeke P, Desomer A, Ailliet L, Berquin A, Demoulin C, Depreitere B, et al. Low back pain and radicular pain: assessment and management. Good Clinical Practice (GCP) Brussels: Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre (KCE). KCE Reports 287. D/2017/10.273/36. Available from: https://kce.fgov.be/sites/default/files/atoms/files/KCE_287_Low_back_pain_Report_2.pdf 2017.

Jun J, Cha Y, Lee J, Choi J, Choi T-Y, Park W, et al. Korean medicine clinical practice guideline for lumbar herniated intervertebral disc in adults: an evidence based approach. Eur J Integr Med. 2017;9:18–26 Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1876382017300033.

Hong JY, Song KS, Cho JH, Lee JH. An updated overview of low Back pain Management in Primary Care. Asian Spine J. 2017;11(4):653–60.

Surgical Guideline for Lumbar Fusion (Arthrodesis) - Washington State Dept. of Labor & Industries (L&I). Available from: https://www.lni.wa.gov/ClaimsIns/Files/OMD/MedTreat/LumbarfusionUpdate020216.pdf.

de Campos T. Low Back pain and sciatica in over 16s: assessment and management. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Clinical Guidelines; 2016. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng59/resources/low-back-pain-and-sciatica-in-over-16s-assessment-and-management-pdf-1837521693637.

Kassolik K, Rajkowska-labon E, Tomasik T, Pisula-lewadowska A, Gieremek K, Andrzejewski W, et al. Recommendations of the polish society of physiotherapy, the polish society of family medicine and the college of family physicians in Poland in the field of physiotherapy of back pain syndromes in primary health care. Fam Med Prim Care Rev. 2017;19(3):323–34. https://doi.org/10.5114/fmpcr.2017.69299.

Latka D, Miekisiak G, Jarmuzek P, Lachowski M, Kaczmarczyk J. Treatment of lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy. Clinical practice guidelines endorsed by the polish Society of Spinal Surgery. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2016;50(2):101–8.

Toward Optimized Practice (TOP) Low Back Pain Working Group. 2017 December. Evidence-informed primary care management of low back pain: clinical practice guideline. 3rd ed; 2017.

Pangarkar S, Low Back Pain Work Group. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for diagnosis and treatment of low Back pain; 2017.

Van Wambeke P, Desomer A, Ailliet L, Berquin A, Demoulin C, Depreitere B, et al. Low back pain and radicular pain: assessment and management. Good clinical practice (GCP) Brussels: Belgian health care knowledge Centre (KCE); 2017. KCE Reports 287. D/2017/10.273/36.

Dijkers MP, Ward I, Annaswamy T, Dedrick D, Feldpausch J, Moul A, et al. Quality of rehabilitation clinical practice guidelines: an overview study of AGREE II appraisals. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;101(9):1643–55.

Armstrong JJ, Goldfarb AM, Instrum RS, MacDermid JC. Improvement evident but still necessary in clinical practice guideline quality: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;81:13–21.

Gagliardi AR, Brouwers MC. Do guidelines offer implementation advice to target users? A systematic review of guideline applicability. BMJ Open. 2015;5(2):e007047.

Hoffmann-Esser W, Siering U, Neugebauer EA, Brockhaus AC, Lampert U, Eikermann M. Guideline appraisal with AGREE II: systematic review of the current evidence on how users handle the 2 overall assessments. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0174831.

Shojania KG, Sampson M, Ansari MT, Ji J, Doucette S, Moher D. How quickly do systematic reviews go out of date? A survival analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(4):224–33.

Elliott JH, Synnot A, Turner T, Simmonds M, Akl EA, McDonald S, et al. Living systematic review: 1. Introduction-the why, what, when, and how. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;91:23–30.

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:1.

Medicine Io. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. https://doi.org/10.17226/13058.

Armstrong MJ, Mullins CD, Gronseth GS, Gagliardi AR. Impact of patient involvement on clinical practice guideline development: a parallel group study. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):55.

Acuna SA, Huang JW, Scott AL, Micic S, Daly C, Brezden-Masley C, et al. Cancer screening recommendations for solid organ transplant recipients: a systematic review of clinical practice guidelines. Am J Transplant Off J Am Soc Transplant Am Soc Transplant Surg. 2017;17(1):103–14.

Tong A, Chapman JR, Wong G, de Bruijn J, Craig JC. Screening and follow-up of living kidney donors: a systematic review of clinical practice guidelines. Transplantation. 2011;92(9):962–72.

Acuna-Izcaray A, Sanchez-Angarita E, Plaza V, Rodrigo G, de Oca MM, Gich I, et al. Quality assessment of asthma clinical practice guidelines: a systematic appraisal. Chest. 2013;144(2):390–7.

Jarl G, Hellstrand Tang U, Norden E, Johannesson A, Rusaw DF. Nordic clinical guidelines for orthotic treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review using the AGREE II instrument. Prosthetics Orthot Int. 2019;43(5):556.

Chen Y, Yang K, Marusic A, Qaseem A, Meerpohl JJ, Flottorp S, et al. A reporting tool for practice guidelines in health care: the RIGHT statement. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(2):128–32.

Huwiler-Muntener K, Juni P, Junker C, Egger M. Quality of reporting of randomized trials as a measure of methodologic quality. Jama. 2002;287(21):2801–4.

Pussegoda K, Turner L, Garritty C, Mayhew A, Skidmore B, Stevens A, et al. Identifying approaches for assessing methodological and reporting quality of systematic reviews: a descriptive study. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):117.

Disease GBD, Injury I, Prevalence C. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1789–858.

Marciano NJ, Merlin TL, Bessen T, Street JM. To what extent are current guidelines for cutaneous melanoma follow up based on scientific evidence? Int J Clin Pract. 2014;68(6):761–70.

Watine J. Is it time to develop AGREE III? CMAJ. 2019;191(43):E1198.

Akl EA, Meerpohl JJ. Elliott J, Kahale LA, Schunemann HJ, living systematic review N. living systematic reviews: 4. Living guideline recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;91:47–53.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Kenneth Adolf BRITSCH, Avicenna snc, the external English service for language revision.

Funding

The work was supported by the Italian Ministry of Health “Linea 3 – Valutazione della qualità delle attuali linee guida in ortopedia e in riabilitazione” L3042. The funding sources had no controlling role in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation or report writing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SG, CG provided the idea and concept development for the research; SG, CG, VI planned the study design; SG, CG, VI, MB performed data collection; SG, CG, VI performed data analysis; VI, SG, GC, MB, DC interpreted the data; VI, SG, GC drafted the work or substantively revises it. DC, GB, LMS provided critical review (revised manuscript for intellectual content; this does not relate to spelling and grammar checking). All authors approved the submitted version. All authors agreed accuracy and integrity of any part of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper. The manuscript does not contain information about medical device(s)/drug(s).

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1 Supplementary Digital Content 1.

Literature search strategy and list of CPGs appraised with AGREE II.

Additional file 2 Supplementary Digital Content 2.

Items and domains of the AGREE II instrument.

Additional file 3 Supplementary Digital Content 3.

Additional Characteristics of included CPGs.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Castellini, G., Iannicelli, V., Briguglio, M. et al. Are clinical practice guidelines for low back pain interventions of high quality and updated? A systematic review using the AGREE II instrument. BMC Health Serv Res 20, 970 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05827-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05827-w