Abstract

Background

Accurate diagnosis and early treatment are essential in the fight against lymphatic cancer. The application of artificial intelligence (AI) in the field of medical imaging shows great potential, but the diagnostic accuracy of lymphoma is unclear. This study was done to systematically review and meta-analyse researches concerning the diagnostic performance of AI in detecting lymphoma using medical imaging for the first time.

Methods

Searches were conducted in Medline, Embase, IEEE and Cochrane up to December 2023. Data extraction and assessment of the included study quality were independently conducted by two investigators. Studies that reported the diagnostic performance of an AI model/s for the early detection of lymphoma using medical imaging were included in the systemic review. We extracted the binary diagnostic accuracy data to obtain the outcomes of interest: sensitivity (SE), specificity (SP), and Area Under the Curve (AUC). The study was registered with the PROSPERO, CRD42022383386.

Results

Thirty studies were included in the systematic review, sixteen of which were meta-analyzed with a pooled sensitivity of 87% (95%CI 83–91%), specificity of 94% (92–96%), and AUC of 97% (95–98%). Satisfactory diagnostic performance was observed in subgroup analyses based on algorithms types (machine learning versus deep learning, and whether transfer learning was applied), sample size (≤ 200 or > 200), clinicians versus AI models and geographical distribution of institutions (Asia versus non-Asia).

Conclusions

Even if possible overestimation and further studies with a better standards for application of AI algorithms in lymphoma detection are needed, we suggest the AI may be useful in lymphoma diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As a clonal malignancy of lymphocytes, lymphoma are diagnosed in 280,000 people annually worldwide with divergent patterns of clinical behavior and responses to treatment [1]. Based on the WHO classification, non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) derived from mature lymphoid cells brings about 6,991,329 (90.36%) disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) originated from precursor lymphoid cells accounts for 14.81% of DALYs [2, 3]. Since about 30% cases of NHL arise in extranodal sites [4], some are considered very aggressive (i.e., Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in NHL). Early and timely detection of lymphoma are needed to forward the qualified treatment and improve the post-operative quality of life.

Since lymphocyte had diverse physiologic immune function according to lineage and differentiation stage, the classification of lymphomas arising from these normal lymphoid populations is complicated. Imaging is a useful tool in medical science and is invoked in clinical practice to facilitate decision making for the diagnosis, staging, and treatment [5]. Despite advances in medical imaging technology, it is difficult for even experienced hematopathologists to identify different subtypes of lymphoma. Diagnosis of lymphoma is firstly based on the pattern of growth and the cytologic features of the abnormal cells, then clinical, molecular pathology, immunohistochemical, and genomic features are required to finalize the identification of certain subtypes [6]. However, clinical routine methods that enable tissue-specific diagnosis, such as image-guided tumor biopsy and percutaneous needle aspiration, have the shortcomings of subjectivity, costly, and poor classification accuracy [7]. Diagnostic features vary widely (from 14.8 to 27.3%) due to inter-observer variability among experts using multiple imaging methods such as computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and Whole Slide Image (WSI) in the same sample [8]. As diagnostic accuracy of lymphoma depends largely on the clinical judgment of physicians and the technical process of tissue sections, limited health system capacities and competing health priorities in more resource-deprived areas may lack infrastructure and perhaps the manpower to ensure high-quality detection of lymphoma. Therefore, accurate, objective and cost-effective methods are required for the early diagnosis of lymphoma in clinical settings and ultimately provide better guidance for lymphoma therapies.

Artificial intelligence (AI) offers tremendous opportunities in this field. It has the ability to extend the noninvasive study of oncologic tissue beyond established imaging metrics, to assist automatic image classification, and to facilitate performance of cancer diagnosis [9,10,11]. As branches of AI, machine learning (ML) [12, 13] and deep learning (DL) [8, 14] have shown promising results for detection of malignant lymphoma. However, there are no studies systematically assessing the diagnostic performance of AI algorithms in identifying lymphoma. Here, we performed a meta-analysis to assess the diagnostic accuracy of AI algorithms that use medical imaging to detect lymphoma.

Materials and methods

The study protocol was approved on the PROSPERO (CRD42022383386). This meta-analysis was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines [15]. Ethical approval was not applicable.

Search strategy and eligibility criteria

In this study, we searched Medline, Embase, IEEE and the Cochrane library until December 2023. No restrictions were applied around regions, languages, participant characteristics, type of imaging modality, AI models or publication types. The full search strategy was developed in collaboration with a group of experienced clinicians and medical researchers (see Additional file 1).

Eligibility assessment was conducted independently by two investigators, who screened titles and abstracts, and selected all relevant citations for full-text review. Disagreements were resolved through discussion with another collaborator. We included all published studies that reported the diagnostic performance of a AI model/s for the early detection of lymphoma using medical imaging. Studies that met the following criteria were included in the final group: (1) Any study that analyzed medical imaging for diagnosis of lymphoma with AI-based models; (2) Studies that provided any raw diagnostic performance data, such as sensitivity, specificity, area under curve (AUC) accuracy, negative predictive values (NPVs), or positive predictive values (PPVs). The primary outcomes were diagnostic performance indicators. Studies were excluded when they met the following criteria: (1) Case reports, review articles, editorials, letters, comments, and conference abstracts; (2) Studies that used medical waveform data graphics material (i.e., electroencephalography, electrocardiography, and visual field data) or investigated the accuracy of image segmentation rather than disease classification; (3) Studies without the outcome of disease classification or not target diseases; (4) Studies that did not use histopathology and expert consensus as the study reference standard of lymphoma diagnosis; (5) Studies that use animals’ studies or non-human samples; (6) Duplicate studies.

Data extraction

Two investigators independently extracted study characteristics and diagnostic performance data using a predetermined data extraction sheet. Again, uncertainties were resolved by a third investigator. Where possible, we extracted binary diagnostic accuracy data and constructed contingency tables at the reported thresholds. Contingency tables contained true-positive (TP), false-positive (FP), true-negative (TN), and false-negative (FN) values and were used to determine sensitivity and specificity. If a study provided multiple contingency tables for the same or for different AI algorithms, we assumed that they were independent of each other.

Quality assessment

The quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies-AI (QUADAS-AI) criteria was used to assess the risk of bias and applicability concerns of the included studies [16], which is an AI-specific extension to QUADAS-2 [17] and QUADAS-C [18].

Meta-analysis

Hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) curves were used to assess the diagnostic performance of AI algorithms. Hierarchical SROC provided more credibility to the analysis of small sample size, taking both between and within study variation into account. 95% confidence intervals (CI) and prediction regions were generated around averaged sensitivity, specificity, and AUCs estimates in Hierarchical SROC figures. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic. We performed subgroup and regression analyses to explore the potential effects of different sample size (≤200 or > 200), diagnostic performance using the same dataset (AI algorithms or human clinicians), AI algorithms (ML or DL), geographical distribution (Asia or non-Asia), and application of transfer learning (Yes or No). The random effects model was implemented since the assumed differences between studies. The risk of publication bias was assessed using funnel plot.

We evaluated the quality of included studies by RevMan (Version 5.3). A cross-hairs plot was produced (R V.4.2.1) to better display the variability between sensitivity/specificity estimates. All other statistical analyses were conducted using Stata (Version 16.0). Two-sided p < 0.05 was the threshold for statistical significance.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

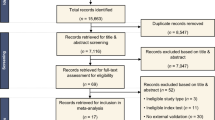

Our search initially identified 1155 records, of which 1110 were screened after removing 45 duplicates. 1010 were also excluded as they did not fulfill our predetermined inclusion criteria. A total of 100 full-text articles were reviewed, 70 were excluded, and the remaining 30 focused on lymphomas (see Fig. 1) [1, 8, 12,13,14, 19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]. Study characteristics are summarized in Tables 1, 2 and 3.

Twenty-nine studies utilized retrospective data. Only one study used prospective data. Six studies used data from open access sources. Five studies excluded low-quality images, while ten studies did not report anything about image quality. Six studies performed external validation using the out-of-sample dataset, fifteen studies did not report type of internal validation while the others performed internal validation using the in-sample dataset. Seven studies utilized ML algorithms and twenty-three studies used DL algorithms to detect lymphoma. Three studies compared AI algorithms against human clinicians using the same dataset. Among the studies analyzed, six utilized samples diagnosed with PCNSL, six involved samples with DCBCL, four studies focused on ALL, while two studies focused on NHL. Additionally, individual studies were conducted among patients with ENKTL, splenic and gastric marginal zone lymphomas, and ocular adnexal lymphoma. Furthermore, a variety of medical imaging modalities were employed across the studies: six studies utilized MRI, four used WSI instruments, four employed microscopic blood images, three utilized PET/CT, and two relied on histopathology images.

Pooled performance of AI algorithms

Among the included 30 studies, 16 provided enough data to assess diagnostic performance and were thus included in the meta-analysis [1, 12, 14, 20, 22,23,24,25,26, 28, 29, 32, 33, 35,36,37]. Hierarchical SROC curves for these studies are provided in Fig. 2. When averaging across studies, the pooled SE and SP were 87% (95% CI 83–91%), and 94% (95% CI 92–96%), respectively, with an AUC of 0.97 (95% CI 0.95–0.98) for all AI algorithms.

Heterogeneity analysis

All included studies found that AI algorithms were useful for the detection of lymphoma using medical imaging when compared with reference standards; however, extreme heterogeneity was observed. Sensitivity (SE) had an I2 = 99.35%, while specificity (SP) had an I2 = 99.68% (p < 0.0001), see Fig. 3. The detailed results of subgroup and meta-regression analyses are shown in Table 4. The heterogeneity for the pooled specificity and sensitivity are still significant within each subgroup, suggesting potential sources of inter-study heterogeneity among studies with different sample sizes, various algorithms applied, geographical distribution and Al algorithms-assisted clinicians versus pure clinicians. However, the results of meta-regression highlight that only difference in AI algorithms and human clinicians remain statistically significant, indicating a potential source of between-subgroup heterogeneity. Furthermore, a funnel plot was produced to assess publication bias, see Fig. 4. The p value of 0.49 suggests there is no publication bias although studies were widely dispersed around the regression line.

Quality assessment

The quality of included studies was summarized in Fig. 5 by using the QUADAS-AI tool. A detailed assessment for each item based on the domain of risk of bias and concern of applicability has also been provided as Fig. 6. For the subject selection domain of risk of bias, fourteen studies were considered a high or unclear risk of bias due to unreported rational and breakdown of training/validation/test sets, derived from open-source datasets, or not performing image pre-processing. For the index test domain, seventeen studies were considered high or at unclear risk of bias due to not performing external verification, whereas the others were considered at low risk of bias. For the reference standard domain, ten studies were considered an unclear risk of bias due to incorrect classification of target condition.

Subgroup meta-analyses

Considering the stage of development of the algorithm and the difference in nature, we categorized them into ML and DL algorithms and did a sub-analysis. The results demonstrated a pooled SE of 86% (95% CI: 80–90%) for ML and 93% (95% CI: 88–95%) for DL, and a pooled SP of 94% (95% CI: 92–96%) for ML and 92% (95% CI: 87–95%) for DL. Additionally, six studies adopted transfer learning and ten studies did not. The pooled SE for studies that used transfer learning was 88% (80–93%), and 85 (80–89%) for studies that did not. The SP was 95% (92–97%) and 91% (88–93%), respectively.

Three studies presented the diagnostic accuracy between AI algorithms and human clinicians in the same dataset. The pooled SE was 91% (86–94%) for AI algorithms, and human clinicians had 70% (65–75%). The pooled SP was 96% (93–97%) for AI algorithms, and 86% (82–89%) for human clinicians.

Five studies had sample sizes above 200, and eleven studies used samples that were less than 200. For sample sizes under 200 and over 200, respectively, the pooled SE was 88% (84–92%) and 86% (78–91%), and the SP was 91% (87–94%) and 95% (92–97%).

Ten studies were geographically distributed in Asia and six studies were geographically distributed outside Asia. The pooled SE among studies in Asia was 88% (83–91%), whereas non-Asian studies exhibited a SE of 83% (72–90%). The pooled SP was 94% (92–96%) for studies in Asia, and 91% (82–96%) in non-Asian studies.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis on the diagnostic accuracy of AI in lymphoma using medical imaging. After careful selection of studies with full reporting of diagnostic performance, we found that AI algorithms could be used for the detection of lymphoma using medical imaging with an SE of 87% and SP of 94%. We were strictly in line with the guidelines for diagnostic reviews, and conducted a comprehensive literature search in both medical databases, engineering and technology databases to ensure the rigor of the study. More importantly, we assessed study quality using an adapted QUADAS-AI assessment tool, which provides researchers with a specific framework to evaluate the risk of bias and applicability of AI-centered diagnostic test accuracy.

Although our results were largely consistent with previous research, confirming the worries that premier journals have recently raised [5, 44,45,46], none of the previous studies were done specifically on lymphoma. To fulfil this research gap, we strive to identify the best available AI algorithm and then develop it to enhance detection of lymphoma, and to reduce the number of false positives and false negatives beyond that which is humanly possible. Our findings revealed that AI algorithms exhibit commendable performance in detecting lymphoma. Our pooled results demonstrated an AUC of 97%, aligning closely with the performance of established conventional diagnostic methods for lymphoma. Notably, this performance was comparable to emerging radiation-free imaging techniques, such as whole-body magnetic resonance imaging (WB-MRI), which yielded an AUC of 96% (95% CI, 91–100%), and the current reference standard, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (18F-FDG PET/CT), with an AUC of 87% (95% CI, 72–97%) [47]. Additionally, the SE and SP of AI algorithms surpassed those of the basic method of CT, with SE = 81% and SP = 41% [48]. However, the comparison between AI models and existing modalities was inconsistent across studies, potentially attributed to the diverse spectrum of lymphoma subtypes, variations in modality protocols and image interpretation methods, and differences in reference standards [49].

Similar to previous research in the field of image-based AI diagnostics for cancers [5, 50, 51], we observed statistically significant heterogeneity among the included studies, which makes it difficult to generalize our results with larger sample sizes or in other countries. Therefore, we conducted rigorous subgroup analyses and meta-regression for different sample sizes, various algorithms applied, geographical distribution and Al algorithms-assisted clinicians versus pure clinicians. Contrary to earlier findings [52], our results displayed that studies with smaller sample sizes and conducted in Asian regions had higher SE compared with other studies. Significant between-study heterogeneity emerged within the comparison of Al-assisted clinicians and pure clinicians. Despite this, other sources of heterogeneity could not be explained in the results, potentially attributed to the broad nature of our review and the relatively limited number of studies included.

Unlike ML, DL is a young subfield of AI based on artificial neural networks, which are known to have the capabilities to automatically extract characteristic features from images [53]. Moreover, it offers significant advantages over traditional ML methods in the early detection and diagnostic accuracy of lymphoma, including higher diagnostic accuracy [8, 14], more efficient image analysis [13], and the greater ability to handle complex morphologic patterns in lymphoma accurately [1]. Most included studies in this review investigating the use of AI in lymphoma detection employed DL (n = 18), with only six studies using ML. For leukemia diagnosis, the convolutional neural networks (CNN) of DL have been used, e.g., to distinguish between cases with favourable and poor prognosis of chronic myeloid leukemia [54], or to recognize blast cells in acute myeloid leukemia [55]. However, it requires far more data and computational power than ML methods, and is more prone to overfitting. Some included studies that used data augmentation methods adopting affine image transformation strategies such as rotation, translation, and flipping, to make up for data deficiencies [13, 26]. The pooled SE using ML methods was higher compared with studies using DL methods (93% VS 86%), while equivalent SP was observed between these two methods (92% VS 94%). We also discovered that AI models using transfer learning had greater SE (88% VS 85%) and SP (95% VS 91%) than models that did not. Transfer learning refers to the reuse of a pre-trained model on a new task. In transfer learning, a machine exploits the knowledge gained from a previous task to improve generalization about another. Therefore, various studies have highlighted the advantages of transfer learning over traditional AI algorithms including accelerated learning speed, reduced data requirements, enhanced diagnostic accuracy, optimal resource utilization, and improved performance in early detection and diagnostic precision of lymphoma [13, 56]. McAvoy et al. [20]. also reported that implemented transfer learning with a high-performing CNN architecture is able to classify GBM and PCNSL with high accuracy (91–92%). Within this review, no significant differences were observed between studies employing transfer learning and those that did not, as well as studies using ML or DL models, potentially indicating limitations stemming from the restricted size of datasets examined in these studies.

Evidence also suggested that AI algorithms had superior SE (91%) and SP (96%), which manifested better performance than independent detection by human clinicians (70 and 86%). Moreover, these differences were the major source of heterogeneity in the meta-regression analysis. Though AI offers certain advantages over physician diagnosis evidenced by faster image processing rates and continuous work, it does not attach importance to all the information that physicians rely on when evaluating a complicated examination. Of the included studies, only three compared the performance of integrating AI with clinicians and pure algorithms, which also restricts our ability to extrapolate the diagnostic benefit of these algorithms in medical care delivery. In the future, the AI versus physicians dichotomy is no longer advantageous, and an AI-physician combination would drive developments in this field and largely reduce the burden of the healthcare system. On one hand, future non-trivial applications of AI in medical settings may need physicians to combine pieces of demographic information with image data, optimize the integration of clinical workflow patterns and establish cloud-sharing platforms to increase the availability of annotated datasets. On the other, AI could perhaps serve as a cost-effective replacement diagnostic tool or an initial method of risk categorization to improve workflow efficiency and diagnostic accuracy of physicians.

Though our review suggests a more promising future of AI upon current literature, some critical issues in methodology needed to be interpreted with caution:

Firstly, only one prospective study was identified, and it did not provide a contingency table for meta-analysis. In addition, twelve studies used data from open-accessed databases or non-target medical records, and only eleven were conducted in real clinical environments (e.g., hospitals and medical centers). This is well known that prospective studies would provide more favorable evidence [57], and retrospective studies with data sources in silicon might not include applicable population characteristics or appropriate proportions of minority groups. Additionally, the ground truth labels in open-assessed databases were mostly derived from data collected for other purposes, and the criteria for the presence or absence of disease were often poorly defined [58]. The reporting around handling of missing information in these datasets was also poor across all studies. Therefore, the developed models might lack generalizability, and studies utilizing these databases may be considered as studies for proof-of-concept technical feasibility instead of real-world experiments evaluating the clinical utility of AI algorithms.

Second, in this review, only six studies performed external validation. For internal validation, three studies adopted the approach of randomly splitting, and twelve used cross-validation methods. The performance judged by in-sample homogeneous datasets may potentially lead to uncertainty around the estimates of diagnostic performance, therefore it is vital to validate the performance using data from a different organization to increase the generalizability of the model. Additionally, only five studies excluded poor-quality images and none of them were quality controlled for the ground truth labels. This may render the AI algorithms vulnerable to mistakes and unidentified biases [59].

Third, though no publication bias was observed in this review, we must admit that the researcher-based reporting bias could also lead to overestimating the accuracy of AI. Some related methodological guides have recently been published [60,61,62], while the disease-specific AI guidelines were not presented. Since researchers tend to selectively report favorable results, the bias might be likely to skew the dataset and add complexity to the overall appraisal of AI algorithms in lymphoma and its comparison with clinicians.

Fourth, the majority of studies included were performed in the absence of AI-specific quality assessment criteria. Ten studies were considered to have low risk in more than three evaluation domains, while nine studies were considered high risk under the AI-specific risk of bias tool. Previous studies most commonly used the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies (QUADAS-2) tool to assess bias and applicability encouraged by current PRISMA 2020 guidance [63], which does not address the particular terminology that arises from AI diagnostic test studies. Furthermore, it did not take into account other challenges that arise in AI research, such as algorithm validation and data pre-processing. QUADAS-AI provided us with specific instructions to evaluate these aspects [16], which is a strength of our systematic review and will help guide future relevant studies. However, it still faces several challenges [16, 64] including incomplete uptake, lack of a formal quality assessment tool, unclear methodological interpretation (e.g., validation types and comparison to human performance), unstandardized nomenclature (e.g., inconsistent definitions of terms like validation), heterogeneity of outcome measures, scoring difficulties (e.g.,uninterpretable/intermediate test results), and applicability issues. Since most of the relevant studies were more often designed or conducted prior to this guideline, we accepted the low quality of some of the studies and the heterogeneity between the included studies.

This meta-analysis has some limitations that merit consideration. Firstly, a relatively small number of studies were available for inclusion, which could have skewed diagnostic performance estimates. Additionally, the restricted number of studies addressing diagnostic accuracy in each subgroup, such as specific lymphoma subtypes and medical imaging modalities, prevented a comprehensive assessment of potential sources of heterogeneity [65, 66]. Consequently, the generalizability of our conclusions to diverse lymphoma subtypes and varied medical imaging modalities, particularly without the integration of AI models at this current stage, could be limited. Secondly, we did not conduct a quality assessment for transparency since current diagnostic accuracy reporting standards (STARD-2015) [67] is not fully applicable to the specifics and nuances of AI research. Thirdly, several included studies have methodological deficiencies or are poorly reported, which may need to be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, the wide range of imaging technology, patient populations, pathologies, study designs and AI models used may have affected the estimation of diagnostic accuracy of AI algorithms. Finally, this study only evaluated studies reporting the diagnostic performance of AI using medical image, which is difficult to extend to the impact of AI on patient treatment and outcomes.

To further improve the performance of AI algorithms in detecting lymphoma, based on the aforementioned analysis, focused efforts are required in the domains of robust designs and high-quality reporting. To be specific, firstly, a concerted emphasis should be directed towards fostering an augmented landscape of multi-center prospective studies and expansive open-access databases. Such endeavors can facilitate the exploration of various ethnicities, hospital-specific variables, and other nuanced population distributions to authenticate the reproducibility and clinical relevance of the AI model. Therefore, we suggest the establishment of interconnected networks between medical institutions, fostering unified standards for data acquisition, labeling procedures and imaging protocols to enable external validation in professional environments. Additionally, we also call for prospective registration of diagnostic accuracy studies, integrating a priori analysis plan, which would help improve the transparency and objectivity of reporting studies. Second, we would encourage AI researchers in medical imaging to report studies that do not reject the null hypothesis, which might improve both the impartiality and clarity of studies that intend to evaluate the clinical performance of AI algorithms in the future. Finally, though time-consuming and difficult [68], the development of “customized” AI models tailored to specific domains, such as lymphoma, head and neck cancer [69], or brain MRI [70], emerges as a pertinent suggestion. This tailored approach, encompassing meticulous preparations such as feature engineering and AI architecture, alongside intricate calculation procedures like segmentation and transfer learning, could yield substantial benefits for both patients and healthcare systems in clinical application.

Conclusions

This systematic review and meta-analysis appraised the quality of current literature and concluded that AI techniques may be used for lymphoma diagnosis using medical images. However, it should be acknowledged that these findings are assumed in the presence of poor design, methods and reporting of studies. More high-quality studies on the AI application in the field of lymphoma diagnosis with adaption to the clinical practice and standardized research routines are needed.

Availability of data and materials

The search strategy and extracted data contributing to the meta-analysis is available in the supplement document; any additional data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- HL:

-

Hodgkin Lymphoma

- NHL:

-

Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

- DLBCL:

-

Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma

- PCNSL:

-

Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma

- ALL:

-

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

- ENKTL:

-

Extranodal NK/T Cell Lymphoma

- MRI:

-

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- WSI:

-

Whole Slide Image

- PET/CT:

-

Positron Emission Tomography / Computedtomography

- FL:

-

Follicular Lymphoma

- FH:

-

Follicular hyperplasia

- AI:

-

Artificial intelligence

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analyses

- QUADAS-2:

-

Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies 2

- SROC:

-

Summary Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves

- DL:

-

Deep Learning

- CI:

-

Confidence Intervals

- SE:

-

Sensitivity

- SP:

-

Specificity

References

Achi HE, Belousova T, Chen L, Wahed A, Wang I, Hu Z, et al. Automated diagnosis of lymphoma with digital pathology images using deep learning. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2019;49(2):153–60.

Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1204–22.

Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, Harris NL, Stein H, Siebert R, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127(20):2375–90.

Weber AL, Rahemtullah A, Ferry JA. Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the head and neck: clinical, pathologic, and imaging evaluation. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2003;13(3):371–92.

Zheng Q, Yang L, Zeng B, Li J, Guo K, Liang Y, et al. Artificial intelligence performance in detecting tumor metastasis from medical radiology imaging: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;31.

Pileri S, Ascani S, Leoncini L, Sabattini E, Zinzani P, Piccaluga P, et al. Hodgkin's lymphoma: the pathologist's viewpoint. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55(3):162–76.

Mwamba PM, Mwanda WO, Busakhala N, Strother RM, Loehrer PJ, Remick SC. AIDS-related non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in sub-Saharan Africa: current status and realities of therapeutic approach. Lymphoma. 2012;2012.

Syrykh C, Abreu A, Amara N, Siegfried A, Maisongrosse V, Frenois FX, et al. Accurate diagnosis of lymphoma on whole-slide histopathology images using deep learning. NPJ Digit Med. 2020;3:63.

Vaishya R, Javaid M, Khan IH, Haleem A. Artificial intelligence (AI) applications for COVID-19 pandemic. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(4):337–9.

Esteva A, Kuprel B, Novoa RA, Ko J, Swetter SM, Blau HM, et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature. 2017;542(7639):115–8.

Gunasekeran DV, Ting DSW, Tan GSW, Wong TY. Artificial intelligence for diabetic retinopathy screening, prediction and management. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2020;31(5):357–65.

Im H, Pathania D, McFarland PJ, Sohani AR, Degani I, Allen M, et al. Design and clinical validation of a point-of-care device for the diagnosis of lymphoma via contrast-enhanced microholography and machine learning. Nat Biomed Eng. 2018;2(9):666–74.

Li D, Bledsoe JR, Zeng Y, Liu W, Hu Y, Bi K, et al. A deep learning diagnostic platform for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with high accuracy across multiple hospitals. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):6004.

Miyoshi H, Sato K, Kabeya Y, Yonezawa S, Nakano H, Takeuchi Y, et al. Deep learning shows the capability of high-level computer-aided diagnosis in malignant lymphoma. Lab Investig. 2020;100(10):1300–10.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Bmj. 2009;339:b2535.

Sounderajah V, Ashrafian H, Rose S, Shah NH, Ghassemi M, Golub R, et al. A quality assessment tool for artificial intelligence-centered diagnostic test accuracy studies: QUADAS-AI. Nat Med. 2021;27(10):1663–5.

Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):529–36.

Yang B, Mallett S, Takwoingi Y, Davenport CF, Hyde CJ, Whiting PF, et al. QUADAS-C: a tool for assessing risk of Bias in comparative diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(11):1592–9.

Zhou Z, Jain P, Lu Y, Macapinlac H, Wang ML, Son JB, et al. Computer-aided detection of mantle cell lymphoma on (18)F-FDG PET/CT using a deep learning convolutional neural network. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;11(4):260–70.

McAvoy M, Prieto PC, Kaczmarzyk JR, Fernández IS, McNulty J, Smith T, et al. Classification of glioblastoma versus primary central nervous system lymphoma using convolutional neural networks. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):15219.

Park JE, Ryu YJ, Kim JY, Kim YH, Park JY, Lee H, et al. Cervical lymphadenopathy in children: a diagnostic tree analysis model based on ultrasonographic and clinical findings. Eur Radiol. 2020;30(8):4475–85.

Mohlman JS, Leventhal SD, Hansen T, Kohan J, Pascucci V, Salama ME. Improving augmented human intelligence to distinguish Burkitt lymphoma from diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2020;153(6):743–59.

Guan Q, Wan X, Lu H, Ping B, Li D, Wang L, et al. Deep convolutional neural network inception-v3 model for differential diagnosing of lymph node in cytological images: a pilot study. Ann Transl Med. 2019;7(14):307.

Guo R, Hu X, Song H, Xu P, Xu H, Rominger A, et al. Weakly supervised deep learning for determining the prognostic value of (18)F-FDG PET/CT in extranodal natural killer/T cell lymphoma, nasal type. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48(10):3151–61.

Xia W, Hu B, Li H, Shi W, Tang Y, Yu Y, et al. Deep learning for automatic differential diagnosis of primary central nervous system lymphoma and glioblastoma: multi-parametric magnetic resonance imaging based convolutional neural network model. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2021;54(3):880–7.

Zhang Y, Liang K, He J, Ma H, Chen H, Zheng F, et al. Deep learning with data enhancement for the differentiation of solitary and multiple cerebral glioblastoma, lymphoma, and Tumefactive demyelinating lesion. Front Oncol. 2021;11:665891.

Wang H, Zhao S, Li L, Tian R. Development and validation of an (18)F-FDG PET radiomic model for prognosis prediction in patients with nasal-type extranodal natural killer/T cell lymphoma. Eur Radiol. 2020;30(10):5578–87.

Zhang J, Cui W, Guo X, Wang B, Wang Z. Classification of digital pathological images of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma subtypes based on the fusion of transfer learning and principal component analysis. Med Phys. 2020;47(9):4241–53.

Wang Q, Wang J, Zhou M, Li Q, Wang Y. Spectral-spatial feature-based neural network method for acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell identification via microscopic hyperspectral imaging technology. Biomed Opt Express. 2017;8(6):3017–28.

Schouten JPE, Matek C, Jacobs LFP, Buck MC, Bošnački D, Marr C. Tens of images can suffice to train neural networks for malignant leukocyte detection. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):7995.

Nakagawa M, Nakaura T, Namimoto T, Kitajima M, Uetani H, Tateishi M, et al. Machine learning based on multi-parametric magnetic resonance imaging to differentiate glioblastoma multiforme from primary cerebral nervous system lymphoma. Eur J Radiol. 2018;108:147–54.

Shafique S, Tehsin S. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia detection and classification of its subtypes using Pretrained deep convolutional neural networks. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2018;17:1533033818802789.

Kong Z, Jiang C, Zhu R, Feng S, Wang Y, Li J, et al. (18)F-FDG-PET-based radiomics features to distinguish primary central nervous system lymphoma from glioblastoma. Neuroimage Clin. 2019;23:101912.

Weisman AJ, Kieler MW, Perlman SB, Hutchings M, Jeraj R, Kostakoglu L, et al. Convolutional neural networks for automated PET/CT detection of diseased lymph node burden in patients with lymphoma. Radiol Artif Intell. 2020;2(5):e200016.

Kim Y, Cho HH, Kim ST, Park H, Nam D, Kong DS. Radiomics features to distinguish glioblastoma from primary central nervous system lymphoma on multi-parametric MRI. Neuroradiology. 2018;60(12):1297–305.

Styczeń M, Szpor J, Demczuk S, Okoń K. Karyometric comparison of splenic and gastric marginal zone lymphomas. Anal Cell Pathol (Amst). 2012;35(4):297–303.

Guo J, Liu Z, Shen C, Li Z, Yan F, Tian J, et al. MR-based radiomics signature in differentiating ocular adnexal lymphoma from idiopathic orbital inflammation. Eur Radiol. 2018;28(9):3872–81.

Jaruenpunyasak J, Duangsoithong R, Tunthanathip T. Deep learning for image classification between primary central nervous system lymphoma and glioblastoma in corpus callosal tumors. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2023;14(3):470–6.

Hosseini A, Eshraghi MA, Taami T, Sadeghsalehi H, Hoseinzadeh Z, Ghaderzadeh M, et al. A mobile application based on efficient lightweight CNN model for classification of B-ALL cancer from non-cancerous cells: a design and implementation study. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked. 2023;39:101244.

Perry C, Greenberg O, Haberman S, Herskovitz N, Gazy I, Avinoam A, et al. Image-based deep learning detection of high-grade B-cell lymphomas directly from hematoxylin and eosin images. Cancers. 2023;15(21):5205.

Aoki H, Miyazaki Y, Anzai T, Yokoyama K, Tsuchiya J, Shirai T, et al. Deep convolutional neural network for differentiating between sarcoidosis and lymphoma based on [(18)F] FDG maximum-intensity projection images. Eur Radiol. 2023;.

Kaur M, AlZubi AA, Jain A, Singh D, Yadav V, Alkhayyat A. DSCNet: deep skip connections-based dense network for ALL diagnosis using peripheral blood smear images. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13(17).

Hashimoto N, Takagi Y, Masuda H, Miyoshi H, Kohno K, Nagaishi M, et al. Case-based similar image retrieval for weakly annotated large histopathological images of malignant lymphoma using deep metric learning. Med Image Anal. 2023;85:102752.

Gao L, Jiao T, Feng Q, Wang W. Application of artificial intelligence in diagnosis of osteoporosis using medical images: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2021;32(7):1279–86.

Bedrikovetski S, Dudi-Venkata NN, Kroon HM, Seow W, Vather R, Carneiro G, et al. Artificial intelligence for pre-operative lymph node staging in colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2021;21(1):1058.

Kim DW, Jang HY, Kim KW, Shin Y, Park SH. Design characteristics of studies reporting the performance of artificial intelligence algorithms for diagnostic analysis of medical images: results from recently published papers. Korean J Radiol. 2019;20(3):405–10.

Wang D, Huo Y, Chen S, Wang H, Ding Y, Zhu X, et al. Whole-body MRI versus (18)F-FDG PET/CT for pretherapeutic assessment and staging of lymphoma: a meta-analysis. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:3597–608.

Rohren EM, Turkington TG, Coleman RE. Clinical applications of PET in oncology. Radiology. 2004;231(2):305–32.

Klenk C, Gawande R, Uslu L, Khurana A, Qiu D, Quon A, et al. Ionising radiation-free whole-body MRI versus (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT scans for children and young adults with cancer: a prospective, non-randomised, single-Centre study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(3):275–85.

Xu HL, Gong TT, Liu FH, Chen HY, Xiao Q, Hou Y, et al. Artificial intelligence performance in image-based ovarian cancer identification: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;53:101662.

Liang X, Yu X, Gao T. Machine learning with magnetic resonance imaging for prediction of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Radiol. 2022;150:110247.

Song C, Chen X, Tang C, Xue P, Jiang Y, Qiao Y. Artificial intelligence for HPV status prediction based on disease-specific images in head and neck cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2023;95(9):e29080.

Lundervold AS, Lundervold A. An overview of deep learning in medical imaging focusing on MRI. Z Med Phys. 2019;29(2):102–27.

Liu K, Hu J, Wang X, Li L. Chronic myeloid leukemia blast crisis presented with AML of t(9;22) and t(3;14) mimicking acute lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Lab Anal. 2019;33(8):e22961.

Arzoun H, Srinivasan M, Thangaraj SR, Thomas SS, Mohammed L. The progression of chronic myeloid leukemia to myeloid sarcoma: a systematic review. Cureus. 2022;14(1):e21077.

Steinbuss G, Kriegsmann M, Zgorzelski C, Brobeil A, Goeppert B, Dietrich S, et al. Deep learning for the classification of non-Hodgkin lymphoma on histopathological images. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(10).

Seidelmann SB, Claggett B, Cheng S, Henglin M, Shah A, Steffen LM, et al. Dietary carbohydrate intake and mortality: a prospective cohort study and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2018;3(9):e419–e28.

Liu X, Faes L, Kale AU, Wagner SK, Fu DJ, Bruynseels A, et al. A comparison of deep learning performance against health-care professionals in detecting diseases from medical imaging: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The lancet digital health. 2019;1(6):e271–e97.

Yadav S, Shukla S. Analysis of k-Fold Cross-Validation over Hold-Out Validation on Colossal Datasets for Quality Classification. 2016 IEEE 6th International Conference on Advanced Computing (IACC); 2016 27–28 Feb. 2016.

England JR, Cheng PM. Artificial intelligence for medical image analysis: a guide for authors and reviewers. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2019;212(3):513–9.

Park SH, Han K. Methodologic guide for evaluating clinical performance and effect of artificial intelligence Technology for Medical Diagnosis and Prediction. Radiology. 2018;286(3):800–9.

Park SH, Kressel HY. Connecting technological innovation in artificial intelligence to real-world medical practice through rigorous clinical validation: what peer-reviewed medical journals could do. J Korean Med Sci. 2018;33(22):e152.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Bmj. 2021;372:n71.

Fowler GE, Blencowe NS, Hardacre C, Callaway MP, Smart NJ, Macefield R. Artificial intelligence as a diagnostic aid in cross-sectional radiological imaging of surgical pathology in the abdominopelvic cavity: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2023;13(3):e064739.

Heydarheydari S, Birgani MJT, Rezaeijo SM. Auto-segmentation of head and neck tumors in positron emission tomography images using non-local means and morphological frameworks. Pol J Radiol. 2023;88:e365–e70.

Hosseinzadeh M, Gorji A, Fathi Jouzdani A, Rezaeijo SM, Rahmim A, Salmanpour MR. Prediction of cognitive decline in Parkinson's disease using clinical and DAT SPECT imaging features, and hybrid machine learning systems. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13(10).

Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, Gatsonis CA, Glasziou PP, Irwig L, et al. STARD 2015: an updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies. Bmj. 2015;351:h5527.

Xue P, Wang J, Qin D, Yan H, Qu Y, Seery S, et al. Deep learning in image-based breast and cervical cancer detection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. NPJ Digit Med. 2022;5(1):19.

Salmanpour MR, Hosseinzadeh M, Rezaeijo SM, Rahmim A. Fusion-based tensor radiomics using reproducible features: application to survival prediction in head and neck cancer. Comput Methods Prog Biomed. 2023;240:107714.

Rezaeijo SM, Chegeni N, Baghaei Naeini F, Makris D, Bakas S. Within-modality synthesis and novel Radiomic evaluation of brain MRI scans. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(14).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was financially supported by Discipline Construction Project of School of Population Medicine and Public Health, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AYB, MYS and PX contributed to the conception and design of the study. YJ and YMQ provided important feedback on the proposed study design. AYB and MYS wrote the article. AYB, MYS, PX, YMQ and YJ were responsible for revisions. AYB and MYS performed the literature search and data extraction. PX checked the data. AYB performed the data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Search terms and search strategy.

Additional file 2.

PRISMA checklist.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Bai, A., Si, M., Xue, P. et al. Artificial intelligence performance in detecting lymphoma from medical imaging: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 24, 13 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-023-02397-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-023-02397-9