Abstract

Background

Persistent Physical Symptoms (PPS) include symptoms such as chronic pain, and syndromes such as chronic fatigue. They are common, but are often inadequately managed, causing distress and higher costs for health care systems. A lack of teaching about PPS has been recognised as a contributing factor to poor management.

Methods

The authors conducted a scoping review of the literature, including all studies published before 31 March 2023. Systematic methods were used to determine what teaching on PPS was taking place for medical undergraduates. Studies were restricted to publications in English and needed to include undergraduate medical students. Teaching about cancer pain was excluded. After descriptive data was extracted, a narrative synthesis was undertaken to analyse qualitative findings.

Results

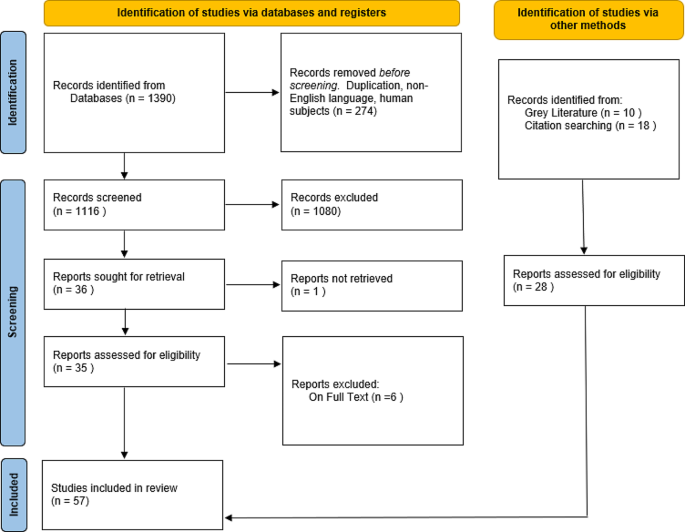

A total of 1116 studies were found, after exclusion, from 3 databases. A further 28 studies were found by searching the grey literature and by citation analysis. After screening for relevance, a total of 57 studies were included in the review. The most commonly taught condition was chronic non-cancer pain, but overall, there was a widespread lack of teaching and learning on PPS. Several factors contributed to this lack including: educators and learners viewing the topic as awkward, learners feeling that there was no science behind the symptoms, and the topic being overlooked in the taught curriculum. The gap between the taught curriculum and learners’ experiences in practice was addressed through informal sources and this risked stigmatising attitudes towards sufferers of PPS.

Conclusion

Faculties need to find ways to integrate more teaching on PPS and address the barriers outlined above. Teaching on chronic non-cancer pain, which is built on a science of symptoms, can be used as an exemplar for teaching on PPS more widely. Any future teaching interventions should be robustly evaluated to ensure improvements for learners and patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Persistent Physical Symptoms (PPS) are symptoms which are disproportionate to currently recognised pathology and are common in all fields of medicine. The term encompasses single symptoms such as pain, dizziness or fatigue, and established syndromes including fibromyalgia and irritable bowel syndrome. It is increasingly understood that PPS arise from complex interactions between the brain and body [1, 2]. While historically terms such as “medically unexplained symptoms” have been in common use, most symptoms can actually be explained [3] and PPS is a more acceptable term to patients [4].

PPS are common and present to nearly every medical specialty. They represent the primary reason for presentation in around 45% of general practice consultations and between 30 and 70% of presentations to neurology, gynaecology, and rheumatology outpatient clinics [5]. People with PPS suffer unduly in a medical system that is predisposed to ‘body part medicine,’ [6] resulting in what Balint referred to as the “collusion of anonymity.” [7] In other words, patients who pass from specialist to specialist, without any doctor taking full responsibility for holistic care. Patients with PPS consult more frequently [8] and tend to have a higher rate of referral to secondary care [9]. This is costly, both in financial terms and in terms of the emotional work for patients and clinicians [10, 11]. Patients with PPS often have a poor experience of the health system and can be left feeling marginalised and even stigmatised [12].

Doctors find it difficult to consult and manage patients with persistent physical symptoms [8]. The absence of a common language of explanation to reconcile patients’ lived experience with doctors’ biomedical models, is particularly problematic [13]. It is plausible that difficulties may arise, or be perpetuated by, issues in each of the three domains of learning: cognitive (knowledge), psychomotor (skills) and affective (attitudes) [14].

The shifting perspectives, particularly around “medically unexplained symptoms” may account for historical uncertainty, however recent adoption of more consistent language and underlying models of symptoms mean that a common curriculum should be possible [15]. It is the authors’ experience that little teaching and learning at the undergraduate level has previously taken place on this topic. We wanted to find out if this was still the case, by reviewing the current medical education literature.

Methods

We carried out a scoping review with narrative synthesis following the approach of Arksey & O’Malley [16]. The PRISMA-ScR guidelines were used to structure reporting [17].

Research questions

The aim of the review was to explore the published literature regarding undergraduate medical teaching and learning on persistent physical symptoms. The specific research questions were:

What teaching and learning on persistent physical symptoms has been described for medical undergraduates?

What teaching methods have been used and how have these been evaluated?

Search strategy

We used a Population, Concept, and Context (PCC) framework to structure a systematic search. The population was undergraduate medical students, the concept was persistent physical symptoms, and the context was teaching and learning. A variety of synonyms were used in order to be inclusive, given the constant evolution of terms for persistent physical symptoms. We used adjacency searching and truncation methods in order to broaden the search as widely as possible and to account for different spellings of words or use of phrases across the international context. Search concepts were then combined using Boolean operators. No date range was used, so all studies before 31 March 2023 were included. Inclusion criteria were: studies relating to the teaching and learning of Persistent Physical Symptoms; medical students included in the population; available in the English language. Exclusion criteria were: studies about cancer or terminal pain without the inclusion of other forms of chronic or persistent pain; population not including medical students; letters to the editor, and papers which were not available in the English language. See Table 1 for the full search strategy.

Sources of evidence

Two authors searched for published literature in MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and Web of Science. Additionally, we searched Google and Google Scholar in order to include any grey literature or sources that had not been picked up by the previous search method. We employed citation analysis, by following backward citations from included papers and analysed the citations of any existing literature reviews.

Study selection

We used a two-stage screening process to identify eligible papers: first at title and abstract level and then at full text. This method was undertaken separately by two reviewers.

Literature reviews were excluded to avoid duplicated representation of primary data, but citations in these reviews were analysed to ensure consistent inclusion of studies and to check for any additional sources.

Charting the data: summary and synthesis

Summary findings for each full text article were charted to determine the most relevant items for extraction. This was an iterative process given the high degree of heterogeneity between the studies. Charting was conducted by two reviewers independently. Discrepancies in charting and data extraction were discussed in review meetings and a consensus was reached regarding which data to include for analysis.

Reviewers extracted descriptive data including: country of origin, whether the study was experimental or observational, the characteristics of the study participants, and whether any teaching intervention was evaluated. Other study characteristics were noted, such as the symptom or syndrome represented, as well as the type of study or intervention.

The expectation was that there would be a lack of teaching and learning on the subject of persistent physical symptoms. For this reason, the scoping review aimed to capture the greatest breadth of studies, rather than exclude studies based on quality criteria. If a teaching intervention was used, we did look at whether this was evaluated using a validated tool.

Following the extraction of descriptive data, a narrative synthesis was undertaken to identify other key findings. An inductive, iterative approach was taken in order to identify themes relating back to the research question. Manual coding was undertaken by two authors independently, followed by a discussion with all authors to arrive at an interpretation of the findings.

Results

Search strategy, study selection, and data extraction

Searches identified 1390 unique titles. Studies were limited to English language and human participants, leading to 274 being excluded. First stage screening excluded a further 1080 studies. It was not possible to retrieve one study and six were excluded on full text. Ten further records were identified through a grey literature search using Google and Google Scholar and 18 were found through citation searching, three of which were from a previous literature review [15]. This resulted in 57 publications for inclusion in the review. See the PRISMA flow diagram in Fig. 1 for a summary of these findings.

PRISMA Diagram

Adapted from Page MJ, et al. [17]

Descriptive analysis

Study types

The studies included for review were highly heterogeneous in their nature. 15/57 (26%) studies employed a teaching intervention, with the remaining either being observational or qualitative. 8/57 (14%) studies described or evaluated the teaching curriculum, 13/57 (22%), included an assessment of the current level of learner knowledge. 9/57 (16%) used qualitative methods with learners and 6/57 (11%) with medical educators. One literature review on assessing knowledge, perceptions and attitudes to pain was found [15]. The citations of this review were checked and the three new sources [18,19,20] were included for review. Sources within this literature review that did not meet the eligibility criteria were excluded. The findings of the review itself were noted for congruity, but not formally analysed.

Study characteristics

23/57(40%) of studies took place in USA and 13/57 (23%) in the UK. Six studies took place in Scandinavia and four in Canada, four in Australia and one in New Zealand, India, and Nigeria respectively. Some studies were based in more than one country e.g. Australia and New Zealand [21]. Publication dates ranged from 1992 to 2022. See Table 2 for a summary of the descriptive data.

Teaching and learning methods

A wide range of teaching and learning methods were discussed in the literature. These are fully described in Table 3, but included lectures, workshops, reflective practice, and forum theatre.

Evaluation of teaching studies

Four studies used validated tools to assess learner attitudes towards patients with PPS, but only one used such a tool to evaluate a teaching intervention [22]. Morris, Rankin, and Briggs used the HC-PAIRS attitudinal questionnaire to assess learner attitudes towards patients with chronic low back pain [18, 23, 24]. Whereas Friedberg et al. [22] used the Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Attitudes Test (CFSAT) and paired t-test to analyse learner attitudes before and after a teaching intervention. The remaining educational interventions either did not use a validated tool for evaluation or were not formally evaluated. See Table 3 for more details.

Thematic synthesis

All studies identified a lack of teaching about persistent physical symptoms (PPS) at undergraduate level. The narrative synthesis identified four themes: An awkward problem, an absence of science, being easily overlooked, and a hidden curriculum.

An awkward problem

PPS was consistently viewed as an awkward problem. Medical educators and learners found it difficult to understand, particularly when referring to the symptoms as ‘unexplained.’ Some educators described PPS as too complex or too confusing, even ‘dangerous’ to introduce at an undergraduate level and stated the need to focus on the easily ‘explainable.’ [25] Chronic non-cancer pain was the dominant condition represented in the literature, but despite theoretical concepts of chronic pain being more established, learners found the subject challenging, even ‘unpleasant.’ [26, 27].

The absence of science

Four studies highlighted that learners infer patients with PPS have ‘no science’ behind their symptoms. In the study by Vasanthy [28], clinical role models in Kerala were found to have a ‘nihilistic’ attitude towards people with fibromyalgia and regarded the condition as benign and unimportant. This finding was echoed by UK studies [29,30,31] where the impact of a lack of teaching and negative role modelling was evident:

“You can’t really train someone for it because there is no science behind it” [30].

One final year medical student stated that fibromyalgia was “not a medical issue” intimating that it had no place in the taught curriculum [29]. Learners understood the need to be supportive and for good communication, but only as a way of achieving relational congruence, not epistemic congruence [8]. Terminology may be important and in one study learners’ attitudes towards PPS varied depending on the diagnostic label [32]. As an example, learners thought that people with myalgic encephalopathy were less likely to recover than those with chronic fatigue syndrome [32].

Easily overlooked

Even without the overt attitudinal barriers described in some studies, PPS as a topic is overlooked in undergraduate medical education. The most common barrier was an already overloaded teaching curriculum [25, 33]. PPS was not deemed a priority area by educational leaders and [33] even when they recognised its importance, they cited a lack of ownership of the topic and a lack of coordination between teaching specialties as a barrier to implementing teaching. This was in contrast to chronic non-cancer pain teaching which usually did have clear ownership by pain specialists and established interdisciplinary relationships [34]. The experience of learners in the clinical setting was that they were shielded from patients with PPS or directed towards patients with other more easily defined clinical problems [28].

Stigma and the hidden curriculum

Given the vacuum of formal teaching, learners were taking on stigmatised messages about sufferers of PPS, frequently from role models in the clinical placement setting. Stenhoff and colleagues described a cycle of negativity created by the lack of teaching on the subject of chronic fatigue, which resulted in negative behaviour by clinical role models, in turn perpetuating negative attitudes in the next generation of learners [31]. Whilst learners recognised the problematic nature of the attitudes towards people with PPS, they lacked the tools to challenge negative stereotypes [29, 30, 35]. Learners experienced a mismatch between formal teaching on the topic and their experience on placement, where these conditions were frequently encountered. They addressed the gap by seeking information about PPS from informal sources, such as their own or their families’ experiences or from the internet [36]. This lack of explicit teaching and the influence of informal sources has been termed by some authors as the ‘hidden curriculum’ [29,30,31, 36] and this has had a significant impact on learners’ attitudes towards people suffering with PPS.

Suggestions for improvement: relationship to domains of learning

The findings of the narrative synthesis map onto Bloom’s revised three domains of learning [14].

Knowledge (cognitive)

A number of studies demonstrate success in teaching on the topic of chronic non-cancer pain. Teaching interventions tended to include a foundation of knowledge such as teaching on pain mechanisms, pharmacology, and pain management [37, 38]. Such theory-driven interventions led to improved scores on assessment [39]. Methods of teaching should be considered in the explicitly taught curriculum. Authors recommended an integrated approach [40, 41] and one which drew on the skills and knowledge from a variety of disciplines [37, 42]. Curriculum mapping was recommended by Howman et al. [33] in order to identify ways in which this integration could be implemented. The need for an holistic approach which emphasises the importance of empathy [41] and the biopsychosocial was also widely recognised [43,44,45,46]. Learners cited a lack of assessment as an indicator that PPS was either unimportant or uncommon [29, 33] and therefore any teaching intervention should include assessment in order to drive learning and engagement.

Skills (psychomotor)

Learners valued the addition of skills-based teaching and engaged best with teaching that was experiential [47] and included either patients with PPS or simulated patients [45, 48, 49]. In one study the focus of the teaching was on interactive, practical teaching for emotionally demanding consultations and the skills taught in such a programme could be transferable to the PPS context [49]. Approaches to help learners find a common language of explanation [13] will not only bridge the epistemic gap between clinicians and patients [8], but should give learners greater confidence and satisfaction in consultations where PPS are the focus.

Attitudes (affective) and the role of reflection

Reflection is a key transferable skill that graduates should acquire as part of their undergraduate training [50]. Both learners and educators voiced a great deal of anxiety regarding teaching and managing patients with PPS. Some authors utilised reflective logs and visual art as a way of teaching about chronic pain [51] and learners valued the deep insights provided by this method. Skills in reflection might help to ameliorate the negative emotions felt by learners, especially if combined with a taught framework that helps them understand concepts such as internal bias and cognitive dissonance [52].

Discussion

Summary of main findings

This review found that teaching on persistent physical symptoms in undergraduate medical education is inconsistent and incomplete. We identified four important themes: an awkward problem, the absence of science, easily overlooked, and the hidden curriculum. Mapping these to teaching and learning domains provides a coherent framework for undergraduate teaching of these common conditions. Where teaching does take place, this is more frequently on the topic of chronic non-cancer pain. A number of studies have demonstrated improved knowledge [39], skills [49], and attitudes [51] as a result of this teaching [34, 47], but high quality evaluation of such teaching and learning is lacking.

Strengths and limitations

This scoping review has addressed a gap in the literature. By undertaking a search of three databases, the grey literature, and citation analysis, a wide range of sources were included for initial screening. Two researchers independently undertook the search strategy before comparing findings which has helped to ensure a robust and systematic approach. Narrative synthesis was undertaken by three researchers, one with expertise in the field of persistent physical symptoms.

The majority of the studies identified were from the USA and UK. Papers that were not accessible in English were excluded, which may explain this finding. Where teaching and learning evaluations had taken place, this was on a small scale usually within one institution. Only one study [22] used a validated tool to evaluate the efficacy of the teaching intervention.

Implications for practice, policy, and research

There is a lack of teaching on PPS in undergraduate medical education. As a result, medical graduates are ill-equipped to recognise, consult for, and manage this group of conditions. Given the prevalence of PPS across medical specialties this is a priority area that needs to be addressed, whilst acknowledging the barriers that exist to implementation.

The solutions offered up in the literature include the need to consider whole-person care, in order to avoid fragmentation and the “collusion of anonymity” [7] described above. For this reason, teaching on PPS should be integrated into the core curriculum and draw on a variety of disciplines.

A better understanding of the science behind PPS [1, 2] is needed for both educators and learners. There is also a need to move learners beyond reductionist models of communication skills towards more theory-driven approaches of person-centredness, as identified by Bansal [53]. We need to convey to learners that skilled communication is not about platitudes, but can make a difference to recovery and addresses the current epistemic gap between clinicians and their patients [8, 13].

Future educational research should focus on the most effective methods to improve the knowledge base of both educators and students and how best to evaluate the success of future teaching interventions. Skills in person-centred communication and explanation [3] need to be taught, alongside those in reflection and challenging prejudice.

Conclusion

We identified four important themes which underpin the challenges of teaching medical undergraduates about persistent physical symptoms. Educational faculties need to find ways to integrate teaching into current programmes and work around the existing barriers to successful implementation and evaluation of teaching about these common and limiting conditions. Examples of successful teaching on chronic non-cancer pain were found in the literature. These tended to articulate the science behind symptoms and often included experiential elements. Such examples should be used to inform an approach for teaching about other forms of PPS. Importantly, robust evaluation that accounts for the complexity of the taught environment is needed to ensure our teaching is making a difference, both for our learners and the patients they will go on to encounter.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Henningsen P, et al. Persistent physical symptoms as Perceptual Dysregulation: a Neuropsychobehavioral Model and its clinical implications. Psychosom Med. 2018;80(5):422–31.

Burton C et al. Functional somatic disorders: discussion paper for a new common classification for research and clinical use BMC Medicine, 2020;18(1).

Morton L, et al. A taxonomy of explanations in a general practitioner clinic for patients with persistent medically unexplained physical symptoms. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(2):224–30.

Picariello F, Ali S, Moss-Morris R, Chalder T. The most popular terms for medically unexplained symptoms: the views of CFS patients. J Psychosom Res. 2015;78(5):420–6.

Haller H, Cramer H, Lauche R, Dobos G. Somatoform disorders and medically unexplained symptoms in primary care. Deutsches Ärzteblatt international, 2015.

Oldham J. Reform reform: an essay by John Oldham. BMJ: Br Med J. 2013;347:f6716.

Balint M. The doctor, his patient and the illness. 2000, Edinburgh: Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2000.

Johansen M-L, Risor MB. What is the problem with medically unexplained symptoms for GPs? A meta -synthesis of qualitative studies. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(4):647–54.

Verhaak PFM. Persistent presentation of medically unexplained symptoms in general practice. Fam Pract. 2006;23(4):414–20.

Mcgorm K, et al. Patients repeatedly referred to secondary care with symptoms unexplained by organic disease: prevalence, characteristics and referral pattern. Fam Pract. 2010;27(5):479–86.

Barsky AJ, Orav EJ, Bates DW. Somatization increases medical utilization and costs Independent of Psychiatric and Medical Comorbidity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(8):903.

Polakovská L, Řiháček T. What is it like to live with medically unexplained physical symptoms? A qualitative meta-summary. Psychology & Health. 2021:pp. 1–17.

Salmon P. Conflict, collusion or collaboration in consultations about medically unexplained symptoms: the need for a curriculum of medical explanation. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67(3):246–54.

Anderson L. A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: a revision of Bloom’s. Pearson new international ed. 2014, Harlow, Essex: Pearson.

Ung A, Salamonson Y, Hu W, Gallego G. Assessing knowledge, perceptions and attitudes to pain management among medical and nursing students: a review of the literature. Br J Pain. 2016;10(1):8–21.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Page MJ et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 2021:p. n71.

Briggs AM, et al. Low back pain-related beliefs and likely practice behaviours among final-year cross-discipline health students. Eur J Pain. 2013;17(5):766–75.

Murinson BB, et al. A new program in pain medicine for medical students: integrating core curriculum knowledge with emotional and reflective development. Pain Med. 2011;12(2):186–95.

Watt-Watson J, et al. An integrated undergraduate pain curriculum, based on IASP curricula, for six Health Science Faculties. Pain. 2004;110(1):140–8.

Shipton EE, et al. Pain medicine content, teaching and assessment in medical school curricula in Australia and New Zealand. Volume 18. BMC Medical Education; 2018:1.

Friedberg F, Sohl SJ, Halperin PJ. Teaching medical students about medically unexplained illnesses: a preliminary study. Med Teach. 2008;30(6):618–21.

Morris H, Ryan C, Lauchlan D, Field M. Do medical student attitudes towards patients with chronic low back pain improve during training? A cross-sectional study. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12(1):10.

Rankin L, Fowler CJ, Stålnacke B-M, Gallego G. What influences chronic pain management? A best–worst scaling experiment with final year medical students and general practitioners. Br J Pain. 2019;13(4):214–25.

Joyce E, et al. Training tomorrow’s doctors to explain ‘medically unexplained’ physical symptoms: an examination of UK medical educators’ views of barriers and solutions. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101(5):878–84.

Corrigan C, et al. What can we learn from First-Year Medical Students’ perceptions of Pain in the primary care setting? Pain Med. 2011;12(8):1216–22.

Wilson JF, et al. Medical students’ attitudes toward pain before and after a brief course on pain. Pain. 1992;50(3):251–6.

Vasanthy B, Parameswaran Nair VC. Fibromyalgia: perspective of patients, medical students and professionals. Journal of evidence based Medicine and Healthcare. J Evid Based Med Healthc. 2018;5(34):2463–7.

Silverwood V et al. ‘If it’s a medical issue I would have covered it by now’: learning about fibromyalgia through the hidden curriculum: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ, 2017;17(1).

Shattock L, et al. They’ve just got symptoms without science’: medical trainees’ acquisition of negative attitudes towards patients with medically unexplained symptoms. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;91(2):249–54.

Stenhoff AL, Sadreddini S, Peters S, Wearden A. Understanding medical students’ views of chronic fatigue syndrome: a qualitative study. J Health Psychol. 2015;20(2):198–209.

Jason LA, et al. Evaluating attributions for an illness based upon the name: chronic fatigue syndrome, myalgic Encephalopathy and Florence Nightingale Disease. Am J Community Psychol. 2002;30(1):133–48.

Howman M, et al. Teaching about medically unexplained symptoms at medical schools in the United Kingdom. Med Teach. 2012;34(4):327–9.

Vargovich AM, et al. Difficult conversations: Training Medical students to assess, educate, and treat the patient with Chronic Pain. Acad Psychiatry. 2019;43(5):494–8.

Yon K, et al. Improving teaching about medically unexplained symptoms for newly qualified doctors in the UK: findings from a questionnaire survey and expert workshop. BMJ Open. 2017;7(4):e014720.

Emorinken A, et al. Assessment of Undergraduate Medical Students Knowledge and Awareness of Fibromyalgia. J Evol Med Dent Sci. 2022;11(5):551–6.

Comer L. Content analysis of chronic pain content at three undergraduate medical schools in Ontario. Can J Pain. 2017;1(1):75–83.

Kolber BJ, Janjic JM, Pollock JA, Tidgewell KJ. Summer undergraduate research: a new pipeline for pain clinical practice and research. BMC Med Educ, 2016;16(1).

Weiner DK, et al. E-Learning Module on Chronic Low Back Pain in older adults: evidence of Effect on Medical Student Objective Structured Clinical Examination performance. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(6):1161–7.

Pöyhiä R, Niemi-Murola L, Kalso E. The outcome of pain related undergraduate teaching in Finnish medical faculties. Pain. 2005;115(3):234–7.

Murinson BB, et al. Recommendations for a New Curriculum in Pain Medicine for Medical students: toward a Career distinguished by competence and Compassion. Pain Med. 2013;14(3):345–50.

Morley-Forster P et al. Mitigating the risk of opioid abuse through a balanced undergraduate pain medicine curriculum. J Pain Res, 2013:p. 791.

Wojtowicz AA, et al. Perceptions of clinical training in biopsychosocial treatment of pediatric functional abdominal pain: a survey of medical students. Clin Pract Pediatr Psychol. 2020;8:37–44.

Dwyer CPM-P, Phoebe E, Durand H, Gormley EM, Slattery BW, Harney OM, MacNeela P, McGuire BE. Factors influencing the application of a Biopsychosocial Perspective in Clinical Judgement of Chronic Pain: interactive management with medical students. Pain Physician. 2017;20(6):E951–60.

Ali N, Thomson DI. A comparison of the knowledge of chronic pain and its management between final year physiotherapy and medical students. Eur J Pain. 2009;13(1):38–50.

Tauben DJ, Loeser JD. Pain Education at the University of Washington School of Medicine. J Pain. 2013;14(5):431–7.

Stevens DL, et al. Medical students retain pain assessment and management skills long after an experiential curriculum: a controlled study. Pain. 2009;145(3):319–24.

Bradner M, et al. Chronic non-malignant pain: it’s complicated. Clin Teach. 2019;16(5):530–2.

Baessler F, et al. Are we preparing future doctors to deal with emotionally challenging situations? Analysis of a medical curriculum. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(7):1304–12.

GMC, Outcomes for Graduates. 2018.

Lempp H, Potter J, Petit P, Hester J. Exploring chronic pain with patients: medicine meets art. Med Educ. 2010;44(11):1139–40.

Syed M. Black box thinking: marginal gains and the secrets of high performance. London: John Murray; 2016.

Bansal A, et al. Optimising planned medical education strategies to develop learners’ person-centredness: A realist review. Medical Education, 2021.

Turner GH, Weiner DK. Essential components of a Medical Student Curriculum on Chronic Pain Management in older adults: results of a modified Delphi process. Pain Med. 2002;3(3):240–52.

Niemi-Murola L, et al. Training medical students to manage a chronic pain patient: both knowledge and communication skills are needed. Eur J Pain. 2006;10(2):167–167.

Saypol B, Schmulson DD. A review of three educational projects using interactive theater to improve physician-patient communication when treating patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2015;107(5):268–73.

Bradshaw YS, et al. Deconstructing one Medical School’s Pain Curriculum: II. Partnering with medical students on an evidence-guided redesign. Pain Med. 2017;18(4):664–79.

Leeds FS, et al. A patient-narrative Video Approach to Teaching Fibromyalgia. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2020;7:238212052094706.

Gadde U, et al. Implementing an interactive introduction to complementary medicine for chronic Pain Management into the Medical School Curriculum. MedEdPORTAL. 2020;16(1):11056.

Campbell WI. What do medical-students know about chronic pain and its management. Ulster Med J. 1992;61(2):139–43.

Chibnall JT, Tait RC, Ross LR. J Behav Med. 1997;20(3):257–71.

Niemi-Murola L, Nieminen JT, Kalso E, Pöyhiä R. Medical undergraduate students’ beliefs and attitudes toward pain - how do they mature? Eur J Pain. 2007;11(6):700–6.

Amber KT, Brooks L, Chee J, Ference TS. Assessing the perceptions of Fibromyalgia Syndrome in United States among Academic Physicians and Medical students: where are we and where are we headed? J Musculoskelet Pain. 2014;22(1):13–9.

Amber KT, Brooks L, Ference TS. Does Improved confidence in a Disease relate to increased knowledge? Our experience with medical students: table 1. Pain Med. 2014;15(3):483–4.

Adillón C, Lozano È, Salvat I. Comparison of pain neurophysiology knowledge among health sciences students: a cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes, 2015. 8(1).

Argyra E, et al. How does an undergraduate Pain Course Influence Future Physicians’ awareness of Chronic Pain concepts? A comparative study. Pain Med. 2015;16(2):301–11.

Briggs EV, et al. Current pain education within undergraduate medical studies across Europe: advancing the provision of Pain Education and Learning (APPEAL) study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(8):e006984.

Hollingshead NA et al. Examining influential factors in providers’ chronic pain treatment decisions: a comparison of physicians and medical students. BMC Med Educ, 2015. 15(1).

Rankin L, Stålnacke B-M, Fowler CJ, Gallego G. Differences in Swedish and Australian medical student attitudes and beliefs about chronic pain, its management, and the way it is taught. Scandinavian J Pain. 2018;18(3):533–44.

Cristóvão I, Reis-Pina P. O Ensino Da Dor Crónica em Portugal: as Perspectivas Dos Estudantes De Medicina E dos internos do Ano Comum. Acta Med Port. 2019;32(5):338.

Gustafsson Sendén M, Renström EA. Gender bias in assessment of future work ability among pain patients – an experimental vignette study of medical students’ assessment. Scandinavian J Pain. 2019;19(2):407–14.

Lechowicz K, et al. Acute and Chronic Pain Learning and Teaching in Medical School—An observational cross-sectional study regarding Preparation and Self-confidence of clinical and Pre-clinical Medical Students. Medicina. 2019;55(9):533.

Storrar A, Rayment D, Mallam E. 47 undergraduate teaching and perceptions of functional neurological disorders. Members’ POSTER abstracts. BMJ Publishing Group Ltd; 2019.

Muirhead N, Muirhead J, Lavery G, Marsh B. Medical School Education on myalgic encephalomyelitis. Medicina. 2021;57(6):542.

Simons J, et al. Disorders of gut-brain interaction: highly prevalent and burdensome yet under‐taught within medical education. United European Gastroenterology Journal, 2022.

Lambson R. Chronic fatigue syndrome: where do your views lie? An experience from a UK Medical Student. Int J Med Students. 2015;3(2):117–8.

Raber I, et al. Qualitative Assessment of Clerkship Students’ perspectives of the topics of Pain and Addiction in their preclinical curriculum. Acad Psychiatry. 2018;42(5):664–7.

Rice K, et al. Medical trainees’ experiences of Treating People with Chronic Pain: a lost opportunity for Medical Education. Acad Med. 2018;93(5):775–80.

Sallay V, et al. Medical educators’ experiences on medically unexplained symptoms and intercultural communication—an expert focus group study. Volume 22. BMC Medical Education. 2022;1.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

CN is undertaking an In Practice Fellowship which has been funded by the NIHR (Reference number NIHR301019). This is an educational award and does not fund direct research costs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Chris Burton: review and editing (equal); formal analysis (supporting). Catie Nagel: Conceptualisation (lead); Methodology (lead); writing – original draft (lead); formal analysis (lead); writing – review and editing (lead). Chloe Queenan: review and editing (supporting); formal analysis (supporting).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Authors’ information

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Nagel, C., Queenan, C. & Burton, C. What are medical students taught about persistent physical symptoms? A scoping review of the literature. BMC Med Educ 24, 618 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05610-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05610-z