Abstract

Background

The social determinants of health (SDH) play a key role in the health of individuals, communities, and populations. Academic institutions and clinical licensing bodies increasingly recognize the need for healthcare professionals to understand the importance of considering the SDH to engage with patients and manage their care effectively. However, incorporating relevant skills, knowledge, and attitudes relating to the SDH into curricula must be more consistent. This scoping review explores the integration of the SDH into graduate medical education training programs.

Methods

A systematic search was performed of PubMed, Ovid MEDLINE, ERIC, and Scopus databases for articles published between January 2010 and March 2023. A scoping review methodology was employed, and articles related to training in medical or surgical specialties for registrars and residents were included. Pilot programs, non-SDH-related programs, and studies published in languages other than English were excluded.

Results

The initial search produced 829 articles after removing duplicates. The total number of articles included in the review was 24. Most articles were from developed countries such as the USA (22), one from Canada, and only one from a low- and middle-income country, Kenya. The most highly represented discipline was pediatrics. Five papers explored the inclusion of SDH in internal medicine training, with the remaining articles covering family medicine, obstetrics, gynecology, or a combination of disciplines. Longitudinal programs are the most effective and frequently employed educational method regarding SDH in graduate training. Most programs utilize combined teaching methods and rely on participant surveys to evaluate their curriculum.

Conclusion

Applying standardized educational and evaluation strategies for SDH training programs can pose a challenge due to the diversity of the techniques reported in the literature. Exploring the most effective educational strategy in delivering these concepts and evaluating the downstream impacts on patient care, particularly in surgical and non-clinical specialties and low- and middle-income countries, can be essential in integrating and creating a sustainable healthcare force.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines the social determinants of health (SDH) as “the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age, that affect a wide range of health and quality of life outcomes.” These conditions are brought about by the nature in which resources, finances, and power are distributed locally, nationally, and globally and may include economic policies and systems, development agendas, social norms, social policies, and political systems [1]. SDH can have a significant impact on individual and population health. Studies have demonstrated that marginalized individuals and communities suffering discrimination have noticeably poorer health outcomes [2]..

There has been a clarion call to integrate SDH concepts for doctors seeking postgraduate training to equip future healthcare professionals with the appropriate competencies to tackle SDH-related factors at the patient and community level [3,4,5]. A critical understanding of the causes and impacts of SDH by doctors is needed to provide effective healthcare while offering adequate stewardship of limited resources and promoting health equity of the populations they serve [6]. Orienting medical training towards SDH is a significant step to equip physicians with the understanding, proficiencies, and attitudes needed to begin to address health inequalities [7].

Medical education regarding the SDH is crucial for future medical practitioners [8]. Besides potentially enhancing health outcomes for individual patients, physicians tackling these disparities will adopt the initiatives calling for changes to influence population and community health [9,10,11]. Thus, understanding social determinants of health requires a perspective shift for graduate learners, with the desired educational outcome being transformative learning [12, 13].

Despite a growing understanding of the importance of integrating SDH into health professional curricula, the optimum approach to incorporating SDH teaching into undergraduate and graduate training curricula has yet to be clarified. A comprehensive guide for SDH teaching strategies would promote consistency in graduate training. A previous scoping review explored the inclusion of SDH in undergraduate medical curricula. The study highlighted the benefits of longitudinal curricula with community involvement in developing retainable knowledge and skills regarding SDH for medical students [14]. In 2019, a scoping review exploring the graduate curriculum interventions focused on SDH objectives concluded the insufficient physician training regarding SDH covers Canada only [15]..

This scoping review was performed to explore the extent of integration of SDH in graduate medical education curricula globally. The study objective was to explore the structure, content, training strategies, and evaluation methods used in incorporating SDH into training qualified doctors seeking higher medical training.

Methods

The scoping review was performed by searching four relevant databases – PubMed, Ovid MEDLINE, ERIC, and Scopus. The process was undertaken by standard scoping review methodology, including identifying the research question, identifying relevant studies, selecting studies, charting the data, and collating, summarizing, and reporting the results [16].

-

i.

Formulation of the research question

All authors formulated the research question, guided by the WHO’s definition of social determinants of health [1]. The overall question: What has been published on the topic of the integration of SDH into graduate medical education curricula? Specifically, the research question focused on the content of the SDH teaching in the graduate medical curriculum, their presentation, teaching strategies, and program evaluation. It aimed to identify any gaps in the available literature to guide future research.

-

ii.

Identification of relevant studies, including the data sources and search strategy

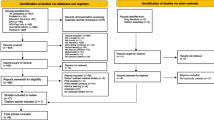

Authors searched PubMed, Ovid MEDLINE, ERIC, and Scopus in March 2023. Individual search strategies were developed for each database, and searches were run for each database (Table 1). The search strategy was comprehensive to capture the diversity of the potential SDH integrated into the graduate medical education curricula. PRISMA-ScR guidelines [17, 18] were followed, as illustrated in (Fig. 1). The study population consisted of medical professionals (doctors) in any discipline undertaking postgraduate training, including specialty trainees, residents, fellows, and registrars; the concept was the content of the curriculum used for teaching the SDH, with the context being graduate medical schools and training health facilities and institutes globally.

-

iii.

Identifying relevant studies

PRISMA flow diagram for the systematic scoping review of the SDH post-graduate training program

*Consider, if feasible to do so, reporting the number of records identified from each database or register searched (rather than the total number across all databases/registers). **If automation tools were used, indicate how many records were excluded by a human and how many were excluded by automation tools. From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71. For more information, visit: (38)

Two authors (DO, NN) reviewed relevant articles after the initial removal of duplicates by exporting the references to Mendeley Reference Manager [19]; articles were analyzed using Rayyan [20], an online software that helps with a blinded screening of articles. Two authors (DO, NN) then independently screened the titles and abstracts without limiting the articles’ publication dates, population, and study locations. The remaining articles underwent full-text screening, and a third author was called to arbitrate where there were differences in screening outcomes.

-

iv.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles were deemed eligible for inclusion if they focused on graduate SDH curricula, including fellows, registrars, trainees, and residents. Studies had to contain structural curricula to qualify for inclusion. Articles published in English between January 2012 and March 2023 were included in the current study. If the program did not intend to integrate the SDH in graduate medical education or did not indicate a mechanism for evaluating the curriculum, they were excluded from this review. Also, the following exclusion criteria were applied: undergraduate programs, reports, systematic reviews, pilot programs, unstructured programs, programs not focusing on SDH teaching, programs not in English, internship studies, and studies that focused on allied health programs such as nursing, public health, global health, dentistry, and pharmacy.

-

xxii.

Charting the data

The main characteristics of each graduate SDH medical curriculum were detailed, including the discipline integrating the program, the program title, length, educational methods, teaching concepts, and methods of curriculum evaluation. In this stage, data from the selected articles were extracted to a Microsoft Excel sheet, and key information about the authors and year of publication was included.

-

vi.

Quality assessment tool.

Two reviewers (DO, NN) performed an independent quality assessment for each article. The Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument (MERSQI) [21] was selected for quality appraisal of the included articles. The appraisal tools assessed the articles over six domains – study design, sampling, type of data, validity of the evaluation, data synthesis, and outcome. All the included articles had a score of 9 and above, which is acceptable.

Results

The original search yielded 970 articles. A total of 141 duplicates were removed. In the initial title and abstract screening step, 829 articles were examined. A further 801 articles were removed upon applying exclusion criteria. The exclusion criteria were: unrelated to SDH (n = 229), associated with undergraduate curricula (n = 129), not curriculum-based (n = 97), irrelevant (n = 71), nursing curricula (n = 62), related to public health and disease prevention (n = 57), allied health curricula (n = 50), considered with global health and elimination of global issues (n = 25), internship (n = 20), unstructured programs (n = 20), social accountability (n = 13), pharmacy curricula (n = 11), dentistry curricula (n = 9) and book chapter (n = 8).

Only 28 articles met the inclusion criteria. The next step was a full examination of the 28 articles that met the inclusion criteria and whose focus was oriented toward the contents of the SDH in graduate medical education. At this point, we removed seven articles as they did not meet the quality assessment criteria.

A total of 21 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review. A hand search through the references of the included articles yielded another four studies; three were deemed eligible for inclusion, and one pilot program was excluded. The final number of articles included in the review was 24.

Summary of the graduate SDH training programs

Of the 24 programs included in the current scoping review, 22 were from graduate residency programs in the United States of America(USA), one from Canada, and one from a residency program in Kenya. Almost 50% (n = 12) of the articles were based on pediatric graduate curricula, while nearly 21% (n = 5) were from internal medicine programs, as indicated in Table 2.

Structure and duration of the postgraduate SDH training

As Table 3 illustrates, of the 24 articles analyzed, the duration of the program relating to SDH varied. Twelve programs had longitudinal modules, spanning one to 3 years in the postgraduate medical residency [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33], while five other programs spanned two to 9 months in the postgraduate medical residency [34,35,36,37,38]. Seven programs took between 2 weeks and 6 weeks [39,40,41,42,43, 43, 44], while the shortest program involved three online simulations; each simulation is 4 hours (one-half day) and completed during a module on advocacy [45].

The structure of the programs related to SDH varied across a range of thematic areas. A total of five courses had a focus on home visits and different community healthcare interventions [23, 30, 31, 40, 41], while another set of 10 programs was in the form of case-based workshops on a variety of topics such as prison healthcare, housing issues locating pharmacies and follow-up of patients after discharge [24,25,26, 28, 29, 32, 34, 39, 43, 45] Lastly, nine programs focused on health advocacy topics, such as opportunities to integrate SDH at community health clinics, housing, education, and legal issues, integration of health disparities to clinical practices and equity, diversity, and inclusion [22, 27, 33,34,35,36,37,38, 44].

Programs presentation methods

The approach to presenting the graduate SDH training and learning activities varied. All the programs used participatory learning, “where the learners are actively participating instead of being passive listeners,” as an educational strategy in combination with other teaching modalities. Eleven programs combined participatory learning with community placement and didactic teaching [23,24,25, 28, 31, 33, 34, 36, 40,41,42]. Another six programs relied on a participatory approach, with community placement and no formal lectures [27, 35, 36, 43,44,45]. Three programs integrated didactic teaching and a participatory approach with no community engagement [29, 37, 38]. Another set of four programs included participatory learning only, requiring participant engagement, such as information gathering, group discussions, and activities [22, 26, 32, 39].

Evaluation of the graduate SDH programs

All the reviewed programs (n = 24) had an evaluation component in their curriculum. Six programs used pre- and post-learning evaluation surveys [24, 25, 30, 32, 35, 38], while 11 programs used only post-learning evaluation surveys [22, 27, 28, 31, 36, 37, 39,40,41, 44, 45]. Three programs used thematic analysis of participants’ written reflections and interviews [26, 34, 44]. One program used both post-course interviews and participants’ reflections analysis [23]. One program combined pre and post-surveys with participants’ reflections [29]. Another program used pre-surveys and post-course reflections [43].Only one program evaluated the participants and the patient’s primary guardians’ views [33].

Five programs evaluated the participants’ affective learning, including their awareness, interest, and empathy combined with their level of knowledge regarding the SDH within the local context [23, 29, 31, 42, 44]. Another three programs used affective learning assessment solely [33, 35, 41]. One program adopted a comprehensive assessment on the three levels, including participants’ attitudes, knowledge, and performance [43]. Another program incorporated knowledge and performance as an evaluation tool [38], and one used the candidate’s performance as the main evaluation aspect [34]. Additionally, 13 programs only used the participants’ knowledge level as an evaluation indicator [22, 24,25,26,27,28, 30, 32, 37, 39,40,41, 45]..

Discussion

This work details a scoping review of literature relating to incorporating the SDH in graduate medical training curricula. Notably, of a total of 24 included articles, 22 programs were implemented in the USA medical schools [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43, 45], with one program in Canada [44] and only one from a low- and middle-income country (Kenya) [22]. The evaluation of the programs varied on different levels; most programs performed post-learning evaluation only for the participants, and only one program added the patient’s perspective on the quality of service provided. The evaluation modules used need more clarity in reporting. The programs with extended training over the years reported a more favorable impact on the knowledge and the participant’s skills regarding SDH concepts. Participants favored training programs that blinded academic knowledge with community placement.

Paediatric training programs took the lead in training healthcare professionals in SDH. Other specialties, such as internal medicine, family medicine, and psychiatry, needed to be more proactive in integrating the SDH into their curriculum. Incorporating SDH concepts for all healthcare training is essential for weaving socially accountable healthcare into healthcare systems [46]..

Participants rated the SDH programs with a multi-year longitudinal structure highly. This finding agrees with other studies suggesting that spiral training programs improve trainees’ community integration, mentorship, confidence, knowledge in evidence-based medicine, patient-centred care, and reflective practice [47,48,49,50].. Our study found heterogeneity in each program’s content, as SDH factors can differ from one geographical location to another. The WHO study states that educators should apply a local context approach to tackle this issue [51]..

All the programs’ teaching strategies involved the participants in the teaching process, so-called “participatory learning.” The programs integrated academic knowledge with community placement and significantly impacted the comprehension of SDH concepts and their application in real-life situations. These findings correlate with studies emphasizing that combining theoretical learning with community engagement will enhance participants’ ability to cultivate an understanding of the core principles of the taught subject [52,53,54,55,56,57]..

Finally, most programs evaluated the participants’ knowledge level and confidence in recognizing SDH-related factors pre- and post, or post-program only. The reported evaluation outcomes included improved knowledge, awareness, and trust in dealing with diverse and underserved communities. Only one program interviewed the patients’ guardians and evaluated the care received by the trained physician [33]. This finding highlights a gap in program evaluation and the need to identify standardized criteria to monitor the success of SDH teaching in postgraduate curricula [58]..

Study limitations and strengths

The number of published articles demonstrating the implementation of SDH training in postgraduate programs is limited. This limitation is likely a significant under-representation of the innovation and scope of SDH integration into postgraduate curricula and again highlights the need for more high-quality literature assessing the effective incorporation, delivery, and assessment of SDH competencies. The scope of articles available in English primarily limited our study. The study focused on the programs including SDH teaching as a separate module not included with public health or global health. Our study is constrained by the unavailability of data from specific databases, which has restricted the scope of our research. Despite these limitations, our study has several strengths. Our study represents a pioneering effort in the field by conducting a comprehensive analysis of integrating SDH into graduate medical training programs. The significance of this research lies in its ability to shed light on the current state of these programs and identify critical areas for improvement. This study displays the heterogeneity of evaluation for such training programs and the deficiency in following the downstream impact of this training on patients’ health. These findings further support questions raised by medical education experts such as Sharma et al. (2018), who explained the importance of SDH teaching and the role of educators and training institutions yet criticized the focus on integration rather than evaluation [59]..

Implications for practice and future research

Our review has identified several future research implications; there needs to be more representation of the published literature about the topic in general and from low- and middle-income countries. The different expression of the SDH training programs by the developed countries’ training institutions may be because of the influence of The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). The ACGME approves complete and independent medical education programs in the United States and Canada. The ACGME standards include addressing health equity and enhancing cultural competency through the taught curriculum of the accredited graduate program, which compels medical institutions to integrate SDH into their curricula [60, 61]. This shows the critical influence accrediting bodies have on the content of medical curricula. As the United Nations (UN) stated in 2015, low- and middle-income countries face triple the burden of health issues and, therefore, creating a well-trained healthcare force and robust health system performance will decrease social disparities [62, 63].

Conclusion

Integrating SDH into graduate medical education curricula is a dynamic and evolving area of research and practice. While the literature highlights the growing recognition of the importance of SDH education, it also reveals gaps in standardized curriculum development, assessment strategies, and long-term evaluation. Providing a multi-level structure approach for the methodology, implementation, and evaluation of SDH training programs will allow training bodies and institutions to integrate SDH concepts more effectively and produce a transparent blueprint for others to follow. Addressing these gaps will ensure that medical graduates are prepared to overcome complex SDH in healthcare.

Availability of data and materials

Data are available upon request by the corresponding author.

References

Social determinants of health. https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health. Accessed 16 Jan 2024.

Artiga S, Published EH. Beyond health care: the role of social determinants in promoting health and health equity. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2018. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/beyond-health-care-the-role-of-social-determinants-in-promoting-health-and-health-equity/. Accessed 16 Jan 2024 .

Matejic B, Vukovic D, Milicevic MS, Supic ZT, Vranes AJ, Djikanovic B, et al. Student-centerd medical education for the future physicians in the community: an experience from Serbia. HealthMED. 2012;6:517–24.

Vakani FS, Zahidie A. Teaching the social determinants of health in medical schools: challenges and strategies. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2013;23:99–100.

Hudon C, Dumont-Samson O, Breton M, Bourgueil Y, Cohidon C, Falcoff H, et al. How to better integrate social determinants of health into primary healthcare: various stakeholders’ perspectives. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19.

Bell ML, Buelow JR. Teaching students to work with vulnerable populations through a patient advocacy course. Nurse Educ. 2014;39:236–40.

Lewis JH, Lage OG, Grant BK, Rajasekaran SK, Gemeda M, Like RC, et al. Addressing the social determinants of health in undergraduate medical education curricula: a survey report. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2020;11:369–77.

Mahon KE, Henderson MK, Kirch DG. Selecting tomorrow’s physicians: the key to the future health care workforce. Acad Med. 2013;88:1806.

Alley DE, Asomugha CN, Conway PH, Sanghavi DM. Accountable health communities — addressing social needs through medicare and medicaid. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:8–11.

Braveman P, Gottlieb L. The social determinants of health: it’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep. 2014;(129 Suppl 2 Suppl 2):19–31.

Gottlieb L, Colvin JD, Fleegler E, Hessler D, Garg A, Adler N. Evaluating the accountable health communities demonstration project. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:345–9.

Klein M, Beck AF. Social determinants of health education: a call to action. Acad Med. 2018;93:149–50.

Laven G, Newbury JW. Global health education for medical undergraduates. Rural Remote Health. 2011;11.

Nour N, Stuckler D, Ajayi O, Abdalla ME. Effectiveness of alternative approaches to integrating SDOH into medical education: a scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23.

Hunter K, Thomson B. A scoping review of social determinants of health curricula in post-graduate medical education. Can Med Educ J. 2019;10:e61–71.

Arksey H, O’malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32.

Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid-Based Healthcare. 2015;13:141–6.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–73.

Mendeley Reference Manager | Mendeley. https://www.mendeley.com/reference-management/reference-manager. Accessed 16 Jan 2024.

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5:210.

Cook DA, Reed DA. Appraising the quality of medical education research methods: the medical education research study quality instrument and the Newcastle-Ottawa scale-education. Acad Med. 2015;90:1067–76.

Nelligan IJ, Shabani J, Taché S, Mohamoud G, Mahoney M. An assessment of implementation of community oriented primary care in Kenyan family medicine postgraduate medical education programmes. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2016;8:e1–4.

Goroncy A, Makaroff K, Trybula M, Regan S, Pallerla H, Goodnow K, et al. Home visits improve attitudes and self-efficacy: a longitudinal curriculum for residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:852–8.

Jacobs C, Seehaver A, Skiold-Hanlin S. A longitudinal underserved community curriculum for family medicine residents. Fam Med. 2019;51:48–54.

Ramadurai D, Sarcone EE, Kearns MT, Neumeier A. A case-based critical care curriculum for internal medicine residents addressing social determinants of health. MedEdPortal Publ. 2021;17:11128.

Knox KE, Lehmann W, Vogelgesang J, Simpson D. Community health, advocacy, and managing populations (CHAMP) longitudinal residency education and evaluation. J Patient-Cent Res Rev. 2018;5:45–54.

Christmas C, Dunning K, Hanyok LA, Ziegelstein RC, Rand CS, Record JD. Effects on physician practice after exposure to a patient-centered care curriculum during residency. J Grad Med Educ. 2020;12:705–9.

Morrison JM, Marsicek SM, Hopkins AM, Dudas RA, Collins KR. Using simulation to increase resident comfort discussing social determinants of health. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21:601.

Mullett TA, Rooholamini SN, Gilliam C, McPhillips H, Grow HM. Description of a novel curriculum on equity, diversity and inclusion for pediatric residents. J Natl Med Assoc. 2022;113:616–25.

Tschudy MM, Platt RE, Serwint JR. Extending the medical home into the community: a newborn home visitation program for pediatric residents. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13:443–50.

Lochner J, Lankton R, Rindfleisch K, Arndt B, Edgoose J. Transforming a family medicine residency into a community-oriented learning environment. Fam Med. 2018;50:518–25.

Lazow MA, Real FJ, Ollberding NJ, Davis D, Cruse B, Klein MD. Modernizing training on social determinants of health: a virtual neighborhood tour is noninferior to an in-person experience. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18:720–2.

Real FJ, Beck AF, Spaulding JR, Sucharew H, Klein MD. Impact of a neighborhood-based curriculum on the helpfulness of pediatric residents’ anticipatory guidance to impoverished families. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20:2261–7.

Daya S, Choi N, Harrison JD, Lai CJ. Advocacy in action: medical student reflections of an experiential curriculum. Clin Teach. 2021;18:168–73.

O’Toole JK, Burkhardt MC, Solan LG, Vaughn L, Klein MD. Resident confidence addressing social history: is it influenced by availability of social and legal resources? Clin Pediatr. 2012;51:625–31.

Gard LA, Cooper AJ, Youmans Q, Didwania A, Persell SD, Jean-Jacques M, et al. Identifying and addressing social determinants of health in outpatient practice: results of a program-wide survey of internal and family medicine residents. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20:18.

Traba C, Jain A, Pianucci K, Rosen-Valverde J, Chen S. Down to the last dollar: utilizing a virtual budgeting exercise to recognize implicit bias. MedEdPortal : J Teach Learn Resour. 2021;17:11199.

Lax Y, Braganza S, Patel M. Three-tiered advocacy: using a longitudinal curriculum to teach pediatric residents advocacy on an individual, community, and legislative level. J Med Educat Curri Develop. 2019;6:2382120519859300–2382120519859300.

Bradley J, Styren D, LaPlante A, Howe J, Craig SR, Cohen E. Healing through history: a qualitative evaluation of a social medicine consultation curriculum for internal medicine residents. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21:95.

Balighian E, Burke M, Davis A, Chinsky J, Tschudy MM, Perin J, et al. A posthospitalization home visit curriculum for pediatric patients. MedEdPortal Publ. 2020;16:10939.

Sufrin CB, Autry AM, Harris KL, Goldenson J, Steinauer JE. County jail as a novel site for obstetrics and gynecology resident education. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4:346–50.

Real FJ, Michelson CD, Beck AF, Klein MD. Location, location, location: teaching about neighborhoods in pediatrics. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17:228–32.

Schmidt S, Higgins S, George M, Stone A, Bussey-Jone J, Dillard R. An experiential resident module for understanding social determinants of health at an academic safety-net hospital. MedEdPortal. 2017;13:10647.

Connors K, Rashid M, Chan M, Walton J, Islam B. Impact of social pediatrics rotation on residents’ understanding of social determinants of health. Med Educ Online. 2022;27.

Lazow MA, DeBlasio D, Ollberding NJ, Real FJ, Klein MD. Online simulated cases assess retention of virtual neighborhood tour curriculum. Matern Child Health J. 2019;23:1159–66.

Murray RB, Larkins S, Russell H, Ewen S, Prideaux D. Medical schools as agents of change : socially accountable medical education. Med J Aust. 2012;196:653.

Maryon-Davis A. How can we better embed the social determinants of health into postgraduate medical training? Clin Med J. 2011;11:61–3.

Bell SK, Krupat E, Fazio SB, Roberts DH, Schwartzstein RM. Longitudinal pedagogy: a successful response to the fragmentation of the third-year medical student clerkship experience. Acad Med. 2008;83:467–75.

Hoeppner MM, Olson DK, Larson SC. A longitudinal study of the impact of an emergency preparedness curriculum. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(Suppl 5 Suppl 5):24–32.

Hense H, Harst L, Küster D, Walther F, Schmitt J. Implementing longitudinal integrated curricula: systematic review of barriers and facilitators. Med Educ. 2021;55:558–73.

Committee on educating health professionals to address the social determinants of health, board on global health, institute of medicine, national academies of sciences, engineering, and medicine. A framework for educating health professionals to address the social determinants of health. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2016.

Bélisle M, Lavoie P, Pepin J, Fernandez N, Boyer L, Lechasseur K, et al. A conceptual framework of student professionalization for health professional education and research. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2021;18.

Hays R. Community-oriented medical education. Teach Teach Educ. 2007;23:286–93.

Lynch CD, Ash PJ, Chadwick BL, Hannigan A. Effect of community-based clinical teaching programs on student confidence: a view from the United Kingdom. J Dent Educ. 2010;74:510–6.

Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, Houweling TAJ, Taylor S. Commission on social determinants of health. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2008;372:1661–9.

Nguemeni Tiako MJ, Johnson SF, Nkinsi NT, Landry A. Normalizing service learning in medical education to sustain medical student-led initiatives. Acad Med. 2021;96:1634.

Bamdas JAM, Averkiou P, Jacomino M. Service-learning programs and projects for medical students engaged with the community. Cureus. 2022;14:e26279.

Kreber C, Brook P. Impact evaluation of educational development programs. Int J Acad Dev. 2001;6:96–108.

Sharma M, Pinto AD, Kumagai AK. Teaching the social determinants of health: a path to equity or a road to nowhere? Acad Med. 2018;93:25–30.

ACGME Home. https://www.acgme.org/. Accessed 7 Jun 2023.

New ACGME Equity Matters TM Initiative Aims to Increase Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion within Graduate Medical Education and Promote Health Equity. https://www.acgme.org/newsroom/2021/7/new-acgme-equity-matters-initiative-aims-to-increase-diversity-equity-and-inclusion-within-graduate-medical-education-and-promote-health-equity/. Accessed 9 May 2023.

Mathers CD. History of global burden of disease assessment at the World Health Organization. Arch Public Health. 2020;78:77.

de Andrade LOM, Filho AP, Solar O, Rígoli F, de Salazar LM, Serrate PC-F, et al. Social determinants of health, universal health coverage, and sustainable development: case studies from Latin American countries. Lancet. 2015;385:1343–51.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank healthcare educators’ efforts to improve social inclusion in the healthcare section and the anonymous reviewers’ helpful comments that improved the manuscript.

Funding

No funding for this study

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript. All authors conceived the manuscript, NN performed the search and analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. SN and PO supported the manuscript’s interpretation and analysis and contributed to the writing and editing. DO contributed to the screening, second review, and data analysis. MEA supervised the research, including its conception, and contributed to revising the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This research did not require ethical approval or consent for participation.

Consent to publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Nour, N., Onchonga, D., Neville, S. et al. Integrating the social determinants of health into graduate medical education training: a scoping review. BMC Med Educ 24, 565 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05394-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05394-2