Abstract

Introduction

Mentorship is an essential component of research capacity building for young researchers in the health sciences. The mentorship environment in resource-limited settings is gradually improving. This article describes mentees’ experiences in a mentorship program for junior academicians amid the COVID-19 pandemic in Tanzania.

Methods

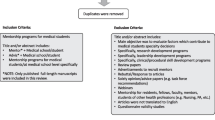

This is a survey study that examined the experiences of mentees who participated in a mentorship program developed as part of the Transforming Health Education in Tanzania (THET) project. The THET project was funded by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) under a consortium of three partnering academic institutions in Tanzania and two collaborating US-based institutions. Senior faculty members of respective academic institutions were designated as mentors of junior faculty. Quarterly reports submitted by mentees for the first four years of the mentorship program from 2018 to 2022 were used as data sources.

Results

The mentorship program included a total of 12 mentees equally selected from each of the three health training institutions in Tanzania. The majority (7/12) of the mentees in the program were males. All mentees had a master’s degree, and the majorities (8/12) were members of Schools/Faculties of Medicine. Most mentors (9/10) were from Tanzania’s three partnering health training institutions. All mentors had an academic rank of senior lecturer or professor. Despite the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the regular weekly meetings between mentors and mentees were not affected. By the fourth year of the mentorship program, more than three-quarters of mentees had published research related to the mentorship program in a peer-reviewed journal, over half had enrolled in Ph.D. studies, and half had applied for and won competitive grant awards. Almost all mentees reported being satisfied with the mentorship program and their achievements.

Conclusion

The mentorship program enhanced the skills and experiences of the mentees as evidenced by the quality of their research outputs and their dissemination of research findings. The mentorship program encouraged mentees to further their education and enhanced other skills such as grant writing. These results support the initiation of similar mentorship programs in other institutions to expand their capacity in biomedical, social, and clinical research, especially in resource-limited settings, such as Sub-Saharan Africa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

The role of mentorship in ensuring that the next generation of researchers is reasonably prepared to handle current, future, and re-emerging global health challenges is very important as research expertise is often the result of good mentorship. Various definitions of mentorship exist. However, in this study, we utilize the one proposed by the Standing Committee on Postgraduate Medical and Dental Education (SCOMPE), which is “A process whereby an experienced, highly regarded, empathetic person (the mentor) guides another (usually younger) individual (the mentee) in the development and re-examination of their ideas, learning, and personal and professional development” [1]. The mentor is often an expert in their field and genuinely invests and becomes interested in their mentee’s goals. A good mentor often encourages open communication, provides structured learning opportunities, and facilitates the career and personal development of the mentee [2, 3]. Therefore, a successful mentor-mentee relationship requires the active participation of both parties, who treat each other as partners in promoting the mentees’ professional development [4, 5].

Within academic institutions, mentorship environments equip junior faculty with the confidence, skills, and knowledge needed to excel in their careers. Thus, effective mentorship is a critical determinant of academic success [6, 7]. Mentorship provides a platform for structured professional growth, as young or emerging researchers in health science institutions navigate between their demanding clinical duties and the demands of establishing their research expertise [7,8,9,10]. A well-organized mentor-mentee relationship enables the mentee to easily access and establish networking opportunities and evolve into an independent professional. Additionally, a good mentorship initiative can accelerate research productivity, career development, and academic promotion [11,12,13,14,15].

To date, there is an increasing body of evidence on the success of research mentorship programs [16, 17]. However, most accounts are from the mentors’ points of view [18, 19], and to the best of our knowledge, few mentees’ experiences have been documented [20, 21]. Further, few have described mentorship experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic in resource-limited settings. To address these shortcomings in the research literature, we aimed to describe the experiences of the mentees who participated in the Community of Young Research Peers (CYRP) during the first three and a quarter years of the Transforming Health Education in Tanzania (THET) project [16]. We examined the successes and challenges of the mentorship program and the resilience of the mentees during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Materials and methods

Settings and establishment of the mentorship program

This was survey research done to understand CYRP (mentees’) experiences during the implementation of the THET project [22]. THET is a consortium of three health universities in Tanzania, the Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (MUHAS), Kilimanjaro Christian Medical University College (KCMUCo), and the Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences (CUHAS), and two partnering US-based institutions, the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) and Duke University, North Carolina [22]. The overarching aim of the THET project was to use innovative educational strategies to transform health education and produce competent health professionals. One of the project’s sub-aims was geared toward the mentorship of junior faculty members who worked in local academic institutions. The THET project sought to promote research mentorship at higher learning institutions in Tanzania by designing and implementing a mentorship program, Community of Young Research Peers (CYRP). This mentorship program has five foundational principles: (1) to be self-governed by the mentees; (2) to provide peer-to-peer mentoring; (3) to provide mentees with the opportunity to provide mentorship to undergraduate students; (4) to provide mentees with the opportunity to undertake research training; and (5) to provide mentees with the opportunity to participate in mentored research projects [22].

The overarching goals of the CYRP were to: (1) promote peer-to-peer mentoring; (2) promote research training within and outside of the three institutions; (3) elicit innovation and academic outputs; (4) promote new approaches in research and redefine priority research needs, and (5) strengthen multidisciplinary research collaborations, especially in the area of HIV/AIDS. The CYRP mentorship program was divided into two cohorts. The first cohort began in the year 2018 and the second cohort was established in 2022; each cohort had twelve members equally distributed among the three universities. The present study examines only the experiences of the first CYRP cohort. Members of the first CYRP cohort were selected by a committee of senior faculty from the partnering institutions based on strength of the research concept notes submitted by junior faculty members.

Detailed information about CYRP selection and project implementation has been documented previously [22]. All mentees were below 40 years of age at the time of recruitment into the program. The characteristics of the CYRP are shown in Table 1.

Mentors of the program

A group of senior faculty members was selected from the partnering institutions as mentors based on the following criteria: academic position of senior lecturer or above; expertise in HIV/AIDS research, basic sciences, implementation science, or socio-behavioral sciences; expertise in research methodology and/or data analysis; and willingness to mentor junior faculty members. Ten senior faculty members (three from each of the partner institutions in Tanzania and one from Duke University) constituted the team of mentors for the CYRP (see Table 2). Mentors could mentor mentees in their respective institutions or other partner institutions and were not restricted to a single mentee. Both mentors and mentees were able to choose each other based on their fields of expertise, research interests, and goals.

Mentors were involved in each stage of the mentees’ research projects, from conceptualization, proposal writing, data collection, analysis, review of manuscript drafts, selection of journals, and eventually manuscript submission. Mentors also ensured that studies were done professionally, ethically, and timely, and were scientifically sound. Furthermore, mentors organized and conducted workshops and training to foster the research skills of the CYRP mentees. Some of the areas covered included qualitative and quantitative research methods, secondary data analysis, grant writing, manuscript writing, and scientific presentations.

Data collection and analysis

For this study, the data was obtained from quarterly progress reports that were submitted by the mentees to the program coordinator. The quarterly reports contained information about the mentees’ research progress, physical meetings with respective mentors, short courses taken, conferences attended, mentorship from non-CYRP faculty members, and mentorship of undergraduate students, as well as challenges faced. We also analyzed the data from anonymous feedback reports of the mentees’ satisfaction with the program, which were obtained from surveys that had been developed by the program coordinators. Data were analyzed using STATA version 17 (StataCorp LLC). Descriptive statistics have been categorized and presented in Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4.

Results

Mentees’ profiles

We reported the findings from records of the mentees tracked over four years. A total of 12 mentees were enrolled in the first cohort, four from each Tanzanian partnering institution. All mentees were faculty members in their respective institutions. The majority, 7/12 were males, and 6/12 were faculty members in departments in schools of medicine (Table 1).

Mentors’ profiles

Most of the mentors were male (9/10); 6 of 10 were faculty members in schools of medicine; 2 of 10 were Senior Lecturers, 4 of 10 were associate professors, and 4 of 10 were professors (Table 2).

Achievements of mentees in the first 4 years of the mentorship project

By the end of the first quarter of the fourth year of the program, most of the mentees (9/12) had at least one published or accepted manuscript out of their respective mentored research projects; 10 of 12 had registered for a Ph.D. fellowship; and 7 of 12 had applied for and received research grants for their research program (Table 3).

Assessment of the mentees’ satisfaction with the quality of the mentorship program

In Table 4, most mentees (10/12) were satisfied with the quality of physical meetings conducted in the mentorship program; 8 of 12 were satisfied with the quality of the mentor-mentee relationship; 9 of 12 were satisfied with the quality of their meetings with institutional leaders. Most mentees (8/12) were satisfied with the assistance provided by institutional administrative staff regarding their queries, and 9 of 12 felt that the overall program had a positive effect on their careers. Most mentees (10/12) were satisfied with the quality of video conference sessions, and 10 of 12 agreed that it was easy to find enough time with their primary mentors. Seven of 12 mentees were satisfied with the mentorship training program, and most mentees (10/12) noted that overall, the program goals were achieved. Less than half of the mentees (5/12) reported a weekly mentor-mentee interaction, (3/12) had bi-weekly interactions, and (2/12) reported a monthly interaction with their mentor.

Impact of COVID-19 on the mentorship program

A challenge encountered during the implementation of the mentorship program was the emergency of COVID-19. Globally, during the pandemic, many governments imposed travel restrictions and lockdowns that interrupted physical attendance at international scientific conferences. In Tanzania, the first COVID-19 patient was reported in March 2020 reading to a series of other cases [23]. It was during this time that the government halted all research activities involving physical contact for several weeks. Due to that, the physical meetings between mentors and mentees were halted. Apart from physical meetings, the mentees also suspended some research activities, especially the enrollment of participants and the order of laboratory reagents. To mitigate some of the challenges, mentees willingly switched to virtual meetings with mentors, and the discussions on the individual project progress as well as lectures on topics such as data analysis, scientific paper writing, and presentations were ongoing.

Discussion

Nurturing the research careers of young investigators is of paramount importance for sustainable growth and ensuring research expertise in resource-limited settings in sub-Saharan Africa. Mentoring is an important component of this endeavor. Mentorship from more experienced academicians and investigators has positive and productive results. The mentorship model in the CYRP program has resulted in mentee success as demonstrated by high outputs in terms of deliverables, which included mentees registering for Ph.D. studies, presenting study findings at national and international scientific conferences, and publishing articles from mentored research projects in international peer-reviewed scientific journals.

Furthermore, the mentees were successful in obtaining external research fellowships and research grants, which sets the ground for their successful future research careers [22]. Additionally, the disposition towards mentorship was established among the mentees, who mentored junior faculty members as well as undergraduate students. These actions support the sustainability of mentorship practices in the three partnering institutions and other similar institutions where the mentees are likely to serve during their careers.

A satisfactory mentor-mentee relationship is dependent on the characteristics of both parties. And according to Straus and colleagues, reciprocity between parties, having shared values and clearly defined goals, and personal connections are critical to a fruitful and satisfactory mentor-mentee relationship [24]. This is consistent with the findings of this study as most mentees reported having a satisfactory relationship with their mentors. Furthermore, a fruitful mentoring relationship ought to be mutually beneficial despite the inherent differences in power and experience that exist between a mentor and a mentee [25]. However, some mentees indicated that they were dissatisfied with the mentorship program in various aspects, including the quality of mentor-mentee relationships with their institutional mentors, the quality of meetings with institutional mentors, video conference sessions, and the overall training during the mentorship program. Similar observations have been reported elsewhere [2, 26,27,28,29]. Although these concerns were observed among a few mentees, further research is needed to explore and adequately address the challenges to ensure the future success of similar programs.

Several practical steps can be implemented in similar mentorship programs to address the challenges. For instance, the new mentees can be informed about previous experiences, including the success and challenges, and they can suggest and work on ways to overcome the challenges as well as adopt and improve the previous success strategies. Mentors too, need to be aware of the previous mentees’ and mentors’ experiences and choose the best ways to improve the mentorship program and attain the best out of it. For instance, Cabana et al. highlighted that The American Academy of Pediatrics continues to promote and encourage efforts to facilitate the creation of new knowledge and ways to reduce barriers experienced by trainees, practitioners, and academic faculty pursuing research [25]. Continued progress in mentoring new researchers can be made by systematic research revealing best practices for fostering positive relationships. Studies focusing on the most salient challenges of mentees and identifying their effective strategies for working with mentors hold promise for enhancing the education and training of medical researchers.

Moreover, as the impact of COVID-19 was being felt by all works of life, research was not spared. Mentees’ research activities including laboratory, field visits, and face-to-face interviews stalled for a few weeks leading to missed deadlines to accomplish the studies. These shortfalls are also echoed by academicians and researchers in developed countries [30, 31]. And according to Bansal et al, the disruption of planned research activities by the COVID-19 outbreak could have equally affected the “lifelong career trajectory” of upcoming researchers [32]. However, more research is still needed to deeply understand its impacts in developing countries and how it has reshaped our approach to health research.

This study possesses some methodological limitations. It used data collected from progress reports submitted quarterly by the mentees (CYRPs) as part of the THET project management. This might have contributed to missed information and a narrow focus on understanding mentees’ experiences and satisfaction with the mentorship program. However, this is a limitation of many studies utilizing secondary data. Secondly, the authors of this study were also the mentees from whom the reports were collected during the mentorship period which could lead to a potential bias. However, this was mitigated by ensuring that only data contained in the progress reports were reported.

Conclusion

Mentoring early career investigators through the multidisciplinary CYRP was a viable model for the growth and development of research expertise. The mentorship program enriched the skills and experiences of the mentees and enhanced the quality of their research outputs, resulting in the dissemination of research findings at international conferences and peer-reviewed publications. We recommend similar mentorship programs to other institutions of higher learning to increase the number of young faculty from diverse backgrounds in health sciences. This could sustainably expand the capacity of clinical research for the present and future generations, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa where resources are limited.

Data Availability

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CUHAS:

-

Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences.

- KCMUCo:

-

Kilimanjaro Christian Medical University College.

- MUHAS:

-

Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences.

- SCOMPE:

-

Standing Committee on Postgraduate Medical and Dental Education.

- CYRP:

-

Community of Young Research Peers.

- THET:

-

Transforming Health Professions Education in Tanzania.

- UCSF:

-

University of California, San Francisco.

References

SCOPME. 1998: SCOPME (Standing Committee on Postgraduate Medical and Dental Education). Supporting Doctors and Dentists at Work: An Enquiry into Mentoring. SCOPME, London 1998)

Straus SE, Chatur F, Taylor M. Issues in the Mentor-Mentee Relationship in academic medicine: a qualitative study. Acad Med. 2009;84:135–9.

Katzka DA. How to balance clinical and research works in the current era of academic medicine. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:1177–80.

DuBois DL, Holloway BE, Valentine JC, Cooper H. Effectiveness of mentoring programs for youth: a meta-analytic review. Am J Community Psychol. 2002;30:157–97.

Bixen CE, Papp KK, Hull AL, et al. Developing a mentorship program for clinical researchers. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2007;27(2):86–93.

Rosenkranz SK, Wang S, Hu W. Motivating medical students to do research: a mixed methods study using self-determination theory. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:95.

Steiner J, Curtis P, Lanphear B, Vu K, Main D. Assessing the role of influential mentors in the research development of primary care fellows. Acad Med. 2004;79:865–72.

Winter FD Jr. Einstein: his life and Universe by Walter Isaacson. Proc (Baylor Univ Med Cent). 2007;20:431–2.

Karcher MJ. Cross-age peer mentoring. In: DuBois DL, Karcher MJ, editors. Handbook of youth mentoring. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2005. pp. 266–85.

Karcher MJ. Research in action: cross-age peer mentoring. Volume No 7 in series. Alexandria, VA: MENTOR/National Mentoring Partnership; 2007.

Sambunjak D, Strauss SE, Marusic A. Mentoring in academic medicine a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1103–15.

Johnson MO, Subak LL, Brown JS, et al. An innovative program to train health sciences researchers to be effective clinical and translational research mentors. Acad Med. 2010;85:484–9.

Sakushima K, Mishina H, Fukuhara S, et al. Mentoring the next generation of physician-scientists in Japan: a cross-sectional survey of mentees in six academic medical centers. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:54.

Taylor J. Training new mentees: a manual for preparing youth in mentoring programs. Portland, OR: Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory, National Mentoring Center; 2003.

Ley TJ, Rosenberg LE. The physician-scientist career pipeline in 2005: build it and they will come. JAMA. 2005;294:1343–51.

Balandya E, Sunguya B, Kidenya B, Nyamhanga T, Minja IK, Mahande M, Mmbaga BT, Mshana SE, Mteta K, Bartlett J, Lyamuya E. Joint Research Mentoring through the community of Young Research Peers: a case for a Unifying Model for Research Mentorship at higher Learning Institutions. Adv Med Educ Pract 2022 Apr 21;13:355–67. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S356678. PMID: 35478975; PMCID: PMC9038151.

Taylor CA, Taylor JC, Stoller JK. The influence of mentorship and role modeling on developing Physician–Leaders: views of aspiring and established physician–leaders. J Gen Intern Med. 2009 Oct;24(10):1130–4.

Carey EC, Weissman DE. Understanding and finding mentorship: a review for Junior Faculty. J Palliat Med. 2010 Nov;13(11):1373–9.

Keller TE, Collier PJ, Blakeslee JE, Logan K, McCracken K, Morris C. Early career mentoring for translational researchers: mentee perspectives on challenges and issues. Teach Learn Med. 2014;26(3):211–6.

Chien E, Phiri K, Schooley A, Chivwala M, Hamilton J, Hoffman RM. Successes and Challenges of HIV Mentoring in Malawi: The Mentee Perspective. PLoS One. 2016 Jun 28;11(6):e0158258. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158258. PMID: 27352297; PMCID: PMC4924818.

Alidina S, Tibyehabwa L, Alreja SS, et al. A multimodal mentorship intervention to improve surgical quality in Tanzania’s Lake Zone: a convergent, mixed methods assessment. Hum Resour Health. 2021;19(1):115. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-021-00652-6. Published 2021 Sep 23.

Balandya E, Sunguya B, Gunda DW, Kidenya B, Nyamhanga T, Minja IK et al. Building sustainable research capacity at higher learning institutions in Tanzania through mentoring of Young Research Peers. BMC Med Educ. 2021 Mar 17;21(1):166. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02611-0. PMID: 33731103; PMCID: PMC7967782.

Buguzi S. Covid-19: Counting the cost of denial in Tanzania. BMJ. 2021 Apr 27;373:n1052. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n1052. PMID: 33906903.

Straus SE, Johnson MO, Marquez C, Feldman MD. Characteristics of successful and failed mentoring relationships: a qualitative study across two academic health centers. Acad Med. 2013 Jan;88(1):82–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31827647a0. PMID: 23165266; PMCID: PMC3665769.

Committee on Pediatric Research. Promoting education, mentorship, and support for pediatric research. Pediatrics. 2014;133(5):943–9.

Leary JC, Schainker EG, Leyenaar JK. The unwritten rules of mentorship: facilitators of and barriers to effective mentorship in Pediatric Hospital Medicine. Hosp Pediatr. 2016 Apr;6(4):219–25. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2015-0108. Epub 2016 Jan 1. PMID: 26939592; PMCID: PMC5578603.

Humphrey HJ. Mentoring in academic medicine. Philadelphia, PA: ACP Press; 2010.

Muñoz de Nova JL, Ortega-Gómez M, Abad-Santos F. Research during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Med Clin (Barc). 2021 Jan 8;156(1):39–40. English, Spanish. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medcli.2020.09.001. Epub 2020 Sep 25. PMID: 33268132; PMCID: PMC7518177.

Zerzan JT, Hess R, Schur E, Phillips RS, Rigotti N. Making the most of mentors: a guide for mentees. Acad Med. 2009;84(1):140–4.

Bratan T, Aichinger H, Brkic N, Rueter J, Apfelbacher C, Boyer L, Loss J. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on ongoing health research: an ad hoc survey among investigators in Germany. BMJ Open. 2021 Dec 6;11(12):e049086. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-049086. PMID: 34872995; PMCID: PMC8649878.

Hogg HDJ, Low L, Self JE, Royal College of Ophthalmologists’ Academic and Research Subcommittee, Rahi JS. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the research activities of UK ophthalmologists. Eye (Lond). 2022 Oct 31:1–6. doi https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-022-02293-y. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 36316557; PMCID: PMC9628368.

Bansal A, Abruzzese GA, Hewawasam E, Hasebe K, Hamada H, Hoodbhoy Z, Diounou H, Ibáñez CA, Miranda RA, Golden TN, Miliku K, Isasi CR. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on research and careers of early career researchers: a DOHaD perspective. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2022 Dec;13(6):800–805. doi 10.1017/S2040174422000071. Epub 2022 Mar 4. PMID: 3524121.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Fogarty International Centre of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R25 TW011227, the THET project leadership team, participants of individual research studies, and the administrations of the teaching hospitals for granting the peers permission to conduct their studies in the respective hospitals. We also acknowledge that the authors were the CYRP’s first cohort.

Funding

Fogarty International Centre of the National Institutes of Health, under award number R25 TW011227. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

“AM, GP, DM, BM, TM, DRM, JSM, BM, HHM, MM, MA and EM” conceived the study. “AM” analyzed data, prepared Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4 and wrote the first draft. All authors interpreted the results, critically revised the manuscript, and approved the final version for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics

The project received a waiver of ethical clearance from the MUHAS Research and Ethics Committee (No.DA.282/298/01.C/), as well as Duke University Health System Institutional Review Board (Pro00107296-INIT-1.0). All methods were performed by the Declaration of Helsinki. The mentors are aware of the content of the manuscript and have been permitted to publish it. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Mremi, A., Pancras, G., Mrema, D. et al. Mentorship of young researchers in resource-limited settings: experiences of the mentees from selected health sciences Universities in Tanzania. BMC Med Educ 23, 375 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04369-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04369-z