Abstract

Background

Person-centred care is integral to high-quality health service provision, though concepts vary and the literature is complex. Validated instruments that measure person-centred practitioner skills, and behaviours within consultations, are needed for many reasons, including in training programmes. We aimed to provide a high-level synthesis of what was expected to be a large and diverse literature through a systematic review of existing reviews of validation studies a of instruments that measure person-centred practitioner skills and behaviours in consultations. The objectives were to undertake a critical appraisal of these reviews, and to summarise the available validated instruments and the evidence underpinning them.

Methods

A systematic search of Medline, EMBASE, PsycINFO and CINAHL was conducted in September 2020. Systematic reviews of validation studies of instruments measuring individual practitioner person-centred consultation skills or behaviours which report measurement properties were included. Review quality was assessed with the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses. Details of the reviews, the included validation studies, and the instruments themselves are tabulated, including psychometric data, and a narrative overview of the reviews is provided.

Results

Four reviews were eligible for inclusion. These used different conceptualisations of person-centredness and targeted distinct, sometimes mutually exclusive, practitioners and settings. The four reviews included 68 unique validation studies examining 42 instruments, but with very few overlaps. The critical appraisal shows there is a need for improvements in the design of reviews in this area. The instruments included within these reviews have not been subject to extensive validation study.

Discussion

There are many instruments available which measure person-centred skills in healthcare practitioners and this study offers a guide to what is available to researchers and research users. The most relevant and promising instruments that have already been developed, or items within them, should be further studied rigorously. Validation study of existing material is needed, not the development of new measures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Person-centred care (also termed patient-centred care [1]) has been widely acknowledged as an essential element of high-quality health service provision [2]. The concept of person-centredness has been utilized for roughly half a century and has been applied at different levels, from national healthcare policy to skills as specific as non-verbal communication behaviours [3]. Many different perspectives on, and definitions of, person-centredness exist, thus making it a somewhat contested concept to operationalise [1, 4]. Arguably, these are variations in emphasis within a core theme, though they do have implications for valid measurement.

Consultations are a key component in health care provision which offer an opportunity for patients to discuss issues with practitioners. Practitioners often have multiple tasks within consultations, including eliciting information to aid assessment, and information-giving. Individual practitioners vary in consultation skills and commitment to make the conversation person-centred in practice [5, 6]. In the past two decades person-centred communication skills acquisition has received much greater attention in training programmes [7, 8]. To evaluate the efficacy of training programmes designed to enhance person-centred skills, validated instruments that objectively measure these skills and their use in practice are needed.

Systematic reviews of validation studies of instruments measuring person-centeredness were known to exist prior to undertaking this study, however, it was clear that this literature was diverse, and that such reviews may have different purposes, aims, and inclusion criteria. Reviews have been aimed at identifying and/or appraising instruments for specific conditions (e.g., cancer, [9]), health care settings (e.g., neonatal intensive care units, [10]), or professions (e.g., psychiatrists, [11]). In addition, across existing reviews different conceptualisations of person-centredness frame research questions and selection criteria in distinct ways (e.g., see [12,13,14,15,16]). Consequently, there may be little overlap in the primary studies included in available reviews, and no one review summarises and evaluates the literature as a whole. For these reasons we aimed to provide a high-level synthesis of this complex literature by undertaking a systematic review of reviews. This was intended to provide an overview of how existing systematic reviews are designed and report on validation studies, and to incorporate details of the included instruments. This study thus brings together what is known about available instruments that may be considered for use in training and assessment of person-centred consultation skills among healthcare practitioners, for researchers and research users. This review of reviews was thus not undertaken to identify a particular instrument for a particular purpose, but rather to survey the level of development of, and the strength of the evidence available in, this field of study.

Reflecting these aims, the objectives of this review of reviews were to: 1) undertake a critical appraisal of systematic reviews reporting validation studies of instruments aiming to measure person-centred consultation skills among healthcare practitioners, and 2) identify and summarise the range of validated instruments available for measuring person-centred consultation skills in practitioners, including material on the strength of the validation evidence for each instrument.

Methods

This review followed the process outlined in this section, which followed the development of a study protocol prior to the conduct of the review. We did not prospectively register or otherwise publish the protocol.

Search strategy

Systematic searches were conducted in the electronic databases MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and CINAHL. The search strategy combined different search terms for three key search components: ‘person- or patient centredness’ (Block 1), ‘assessment instrument’ (Block 2), and ‘systematic or scoping review’ (Block 3).

For Block 1 (the search component ‘person- or patient centredness’) we used an iterative approach. A preliminary search of EMBASE, MEDLINE, and PsychInfo (all in Ovid) was undertaken using the keywords: (person-cent* or patient-cent* or personcent* or patientcent*) and ‘review’ in the title; and ‘measurement or tool or scale or instrument’; from 2010. Full text papers identified (n = 24) were searched for words used to describe ‘person- or patient centredness’. The resulting search terms were discussed and selected to reflect the scope of the study. The final search included the following terms: person-cent* or patient-cent* or personcent* or patientcent* or person-orient* or person-focus* or person-participation or person-empowerment or person-involvement or patient-orient* or patient-focus* or patient-participation or patient-empowerment or patient-involvement or "person orient*" or "person focus*" or "person participation" or "person empowerment" or "person involvement" or "patient orient*" or "patient focus*" or "patient participation" or "patient empowerment" or "patient involvement"; or (clinician-patient or physician–patient or professional-patient or provider-patient or practitioner-patient or pharmacist-patient or doctor-patient or nurse-patient) adjacent to (communication* or consultation* or practice* or relation* or interaction* or rapport).

For Block 2 (the search component ‘assessment instrument’) we used the existing COSMIN filters proposed by Terwee et al. [17]. The COSMIN (COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement Instruments) project has developed highly sensitive search filters for finding studies on measurement properties [17]. The search filter was adapted to each database. For Block 3, the search terms (systematic* or scoping) adjacent to review* were used. The search did not include restrictions pertaining to date of publication, and the language was restricted to English. The database search was conducted in September 2020. See appendix 1 for the details of all searches run in all databases.

Study selection

One author (JG) screened titles and abstracts against preliminary selection criteria, using Rayyan software for systematic reviews [18]. Ideally all parts of the process of undertaking a review are duplicated to in order to avoid errors. Here we relied on one author for screening, with the rationale was that we expected systematic reviews to be readily identifiable in the title and abstract, making screening more straightforward, for example, than in conducting a systematic review of primary studies, which may be described in more heterogeneous ways. Another author (AD) screened 5% independently. The authors met weekly to resolve any problems or questions during the process and no contentious issues were identified in screening. Full text articles of potentially eligible papers were retrieved and assessed for inclusion against the criteria below. Two authors (AD & JM) reviewed all full text papers independently in order to select studies for inclusion. One disagreement was resolved through discussion with a third author (DS) and reasons for exclusion were noted. Inclusion criteria were:

-

a peer-reviewed journal report

-

used systematic review methods to identify primary studies for inclusion (including both a search strategy and explicit selection criteria)

-

stated aims and objectives specifying the measurement of ‘person centredness’ or ‘patient centredness’ or a related construct as defined by search Block 1.

-

concerned assessment of individual practitioner consultation skills or behaviour (i.e., not policy)

-

included only validation studies of instruments

-

reported any measurement properties of the included instruments

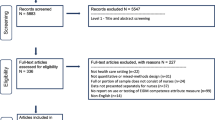

Reviews of instruments developed for any practitioner group, patient population, or health care setting were included. Studies were excluded unless they met all inclusion criteria. After the full text eligibility check, a backwards search of the references of the included reviews, as well as a forward reference search using Google Scholar was performed. This was last updated in January 2022 and no further reviews were identified. A PRISMA flowchart [19] shows the results of the identification, screening, and eligibility assessment process (Fig. 1).

Data extraction

One author (AD) performed data extraction from the included reviews using a standardised form created in Excel developed by all co-authors in a preliminary phase. A second author (DS) subsequently checked all the extracted information in the form, and screened the paper for any missing information. At the review level, we extracted the stated aims and objectives, definition or conceptualisation of person-centredness used, numbers, names and types of instruments, research questions, dates, databases, and languages included in search strategies, selection criteria regarding health care populations, health care settings, raters of the instruments, other selection criteria, details of the assessment of methodological quality and psychometric properties, and numbers of validation studies. At the validation study level, we extracted the country of origin, the type of validation study, and whether the developers of the instrument validated their own instrument. At the instrument level we extracted who developed the instrument, in what year, in which country and in what language the instrument, how many subscales and items the instruments consisted of, and the response formats used. Other information on validation studies and instruments was not reported consistently enough to be extracted.

Quality assessment

Two authors (AD & DS) independently assessed the quality of the included reviews using the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses checklist [20]. Each of the 11 criteria was given a rating of ‘yes’ (definitely done), ‘no’ (definitely not done), ‘unclear’ (unclear if completed) or ‘not applicable’. Discrepancies in the ratings of the methodological reviews were be resolved by consensus.

Results

Description of the reviews

The search identified 2,215 unique articles with 21 papers selected for a full-text eligibility assessment (see Fig. 1). Four studies were included. None of the reviews identified in further searching fulfilled our inclusion criteria.

The four included reviews each had different aims and selection criteria, resulting in few primary studies and instruments being included in more than one review. Two reviews targeted different groups of practitioners; nurses for Köberich and Farin [21] and physicians or medical students for Brouwers et al. [22]). Hudon et al. [23] and Köberich and Farin included only patient rated instruments, while Ekman et al. [24] included only direct observation tools (e.g., checklists or rating scales). In total, the four reviews included 71 validation studies (68 unique studies) of 42 different instruments.

Conceptualisations of person-centredness

Conceptualisations of person-centredness varied between the included studies. Two reviews used Stewart and colleagues [15] model of interconnecting dimensions: 1) exploring both the disease and the illness experience; 2) understanding the whole person; 3) finding common ground between the physician and patient; 4) incorporating prevention and health promotion; 5) enhancing the doctor–patient relationship, and 6) ‘being realistic’ about personal limitations and issues such as the availability of time and resources. Dimensions 4 and 6 were later dropped [14]. Brouwers et al. [22] included instruments measuring at least three out of the six dimensions, while Hudon et al. [23] included those measuring at least two out of the later version of four dimensions. Köberich and Farin [21] used a framework of three core themes of person centredness based on Kitson et al. [13]: 1) participation and involvement; 2) relationship between the patient and the health professional; and 3) the context where care is delivered. Finally, Ekman et al. used an Institute of Medicine framework [16] of six dimensions: 1) respect for patients’ values, preferences, and expressed needs; 2) coordination and integration of care; 3) information, communication, and education; 4) physical comfort; 5) emotional support, e.g., relieving fear and anxiety; and 6) involvement of family and friends (Table 1).

Overview of reviews

Hudon et al.’s review [23] aimed to identify and compare instruments, subscales, or items assessing patients’ perceptions of patient-centred care used in an ambulatory family medicine setting. Only patient rated instruments were included. Quality assessment of the validation studies was conducted with the Modified Version of Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD) tool [25]. The authors identified two instruments fully dedicated to patient-centred care, and 11 further instruments with subscales or items measuring person-centred care.

Köberich and Farin’s review [21] aimed to provide an overview of instruments measuring patients’ perception of patient-centred nursing care, defined as the degree to which the patient’s wishes, needs and preferences are taken into account by nurses when the patient requires professional nursing care. Again, only patient rated instruments were included. The four included instruments were described in detail, including their theoretical background, development processes including consecutive versions and translations, and validity and reliability testing. No quality assessment was undertaken.

Brouwers et al. [22] aimed to review all available instruments measuring patient centredness in doctor–patient communication, in the classroom and workplace, for the purposes of providing direct feedback. Instruments for use in health care professionals other than physicians or medical students were thus excluded. The authors used the COSMIN checklist for quality assessment of the instruments [26].

Ekman et al.’s review [24] aimed to identify available instruments for direct observation in assessment of competence in person-centred care. The study then assessed them with respect to underlying theoretical or conceptual frameworks, coverage of recognized components of person-centred care, types of behavioural indicators, psychometric performance, and format (i.e., checklist, rating scale, coding system). The review used the six-dimension framework endorsed by the Institute of Medicine [16] however, they did not use the framework as a selection criterion. No quality assessment was undertaken. The authors group the included instruments in four categories: global person-centred care/person centredness, shared decision-making, person-centred communication, and nonverbal person-centred communication.

The critical appraisal of the included reviews using the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses is reported in Table 2. The review by Brouwers et al. [22] scored positively on all but one items. We note that no study assessed publication bias, and this may be a particularly important threat to valid inference in a literature of this nature. There were issues with the methods of critical appraisal in two reviews.

Overview of the validation studies

Sixty-eight validation studies were included across the four reviews. Hudon et al. [23] described one to three validation studies for each instrument included and was the only review to report specific information on the validation studies in addition to information on the instruments. Köberich and Farin [21] identified several validation studies for each instrument. Brouwers et al. [22] identified one validation study for each included instrument. Ekman et al. [24] describe one validation study for 13 instruments, and two validation studies for three other included instruments. Table 3 provides an overview of the validation studies [3, 27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91].

The validation studies were published between 1989 and 2015 inclusive. The majority of the studies were done in English speaking countries: 29 originated in the USA, 10 in the UK, 8 in Canada; 4 in Finland; 2 in Australia, the Netherlands, and Turkey; and 1 in Germany, Israel, Norway, and Sweden. The country of origin was not specified for the remaining 7 studies.

Overview of the instruments

Forty-two instruments were included across the four reviews, with minimal overlap. The Patient-Centred Observation Form (PCOF) was included in two reviews [22, 24]. The original Perceived Involvement in Care Scale (PICS) is included by Hudon [23], while Brouwers [22]included the modified PICS (M-PICS). The Consultation and Relational Empathy instrument (CARE), and the Patient Perception of Patient Centeredness (PPPC) are included by both Hudon and Brouwers [22, 23]. Hudon [23] included what they referred to as the Consultation Care Measure (CCM), and Brouwers [22] included the same instrument, named differently as the Little instrument. Little et al. [34] do not name the instrument in their validation study, so we decided to refer to this instrument as the ‘Little Instrument’ in this review of reviews.

The four reviews reported varying types of information on the included instruments. All reported the year and country of development, the response scale, the number of subscales and items, and the intended rater of the instrument. Table 4 gives an overview of what information about the instrument is included in each review.

As with the validation studies, the publication years of the instruments ranged from 1989 up to 2015. The majority of the instruments were developed in English speaking countries: 21 originated from the USA, 7 from the UK, 7 from Canada; 2 from the Netherlands; and 1 from Australia, Finland, Germany, Israel, and Norway. The country of origin was not specified in the review for the remaining 3 instruments. Table 5 summarises the information that is reported in the reviews.

The measurement properties of instruments that were reported in the reviews varied considerably.. Table 6 shows which properties were reported in which review, and Table 7 is a literal presentation of all psychometric information reported in the four included reviews.

Discussion

This review of reviews sought to summarise the range of validated instruments available for measuring practitioners’ person-centred consultation skills, including the strength of the validation evidence for each instrument, and to appraise the systematic reviews examining the validation studies. The reviews varied in quality, and our JBI quality assessment showed only one review which fulfilled all assessment criteria except for the assessment of publication bias [22]. In addition, only one review described several validation studies per instrument, including modifications and translations [21]. We found that the four included systematic reviews used very different inclusion criteria, leading to little overlap in included validation studies and instruments between them. This was because the reviews also differed in aims, appraisal tools used, and conceptual framework used, which limited the consistency of reported information across studies and instruments. These features underline the value of the present study, which in bringing together these literatures offers a guide to a wider set of instruments of interest to researchers than has previously been available. This diversity also underlines a key limitation of this review of reviews, as the included reviews themselves may complicate attention to the primary literature unhelpfully.

We make no claim that the list of instruments reported in this review of reviews is exhaustive. Our search was undertaken in September 2020 and although we have checked for citations of the included reviews and the primary studies, we may have missed later published reviews and instruments. There are many more instruments available, varying in aims, objectives, and conceptualisations of person-centredness. In addition, there may be other validation studies available on the instruments the reviews did not include, or which were published after the reviews, and the study findings suggest it is indeed likely that new instruments will have been published. We searched for all reviews meeting our selection criteria and acknowledge the perennial possibility that we may have missed eligible reviews, as well as being clear that there exist other validation studies and instruments that our study was not designed to include. We used an extensive list of keywords for our search, based on published reviews of person-centredness, but as the concept is so scattered, we may have left out search terms that could have led us to other reviews that could have been included. This we regard as a real risk and suggest careful extension of search strategy development in future studies. Procedural issues, particularly reliance on sole author for screening and data extraction, albeit with checks, should be borne in mind as review limitations.

There are many instruments available which measure person-centred skills in healthcare practitioners. The reviews point out that the instruments measured person-centredness in various dimensions, emphasising different aspects of the basic concept of person-centredness. This indicates the lack of agreement on what could be considered defining, central or important characteristics, so there are construct validity issues to be considered carefully. Person-centred care is an umbrella term used for many different conceptualisations in many different contexts [1, 4]. Separating consideration of what constitutes person centred care from person centred consultation skills is necessary, as the latter construct is merely one element of the former. Often teaching materials and guidelines on person centredness are not very clear on what person-centred behaviour and communication actually entails, and what skills and behaviours health care professionals are supposed to learn to make their practice person-centred. For example, Kitson and colleagues [13] reported that health policy stakeholders and nurses perceive patient-centred care more broadly than medical professionals. Medical professionals tend to focus on the doctor-patient relationship and the decision-making process, while in the nursing literature there is also a focus on patients’ beliefs and values [13]. Measurement instruments can help us operationalise person-centredness and can help practitioners understand what exactly it is that they are supposed to be doing. Developing the science of measurement in this area may also assist resolution of the construct validity issues by making clear what can be validly measured and what cannot.

Three of the four reviews [20, 21, 23] concluded that psychometric evidence is lacking for nearly all of the instruments. This finding may seem unsurprising in light of the foregoing discussion of construct validity. Brouwers [22] used the COSMIN rating scale [26] and found only one instrument rated as ‘excellent’ on all aspects of validity studied (internal consistency, content, and structural validity), but its reliability had not been studied. Köberich [21] specifically mentions test–retest reliability as a neglected domain and adds that all instruments lack evidence of adequate convergent, discriminant, and structural validity testing. Köberich and Farin, Brouwers, and Ekman [21, 22, 24] also highlight the need for further research on validity and reliability of existing instruments in their discussion and conclusion sections. In other reviews, De Silva [92], Gärtner et al. [93] and Louw et al. [94] attribute the lack of good evidence on the measurement qualities of instruments both to a failure to study their measurement properties and to the overall poor methodological quality of validation studies. Many tools are developed but few are studied sufficiently in terms of their psychometric properties and usefulness for research on and teaching of person-centredness. Often, a tool is “developed, evaluated, and then abandoned” [92].

Researchers and research users may seek instruments of these kinds for many different purposes. Using the most relevant and promising instruments that have already been developed and tested, in however a limited fashion, and rigorously studying and reporting on their psychometric properties, will be useful in building the science of measuring person-centred consultation skills. It may also be useful to develop item banking approaches that combine instruments. Researchers or educators intending to choose an instrument for their purposes also need to know several things to decide whether an instrument is relevant and suitable for their specific needs. For future primary studies and systematic reviews, we suggest paying heed to, and indeed rectifying, the limitations of existing studies identified here and elsewhere. In addition, both Hudon and Ekman [23, 24] found that paradoxically, there is very limited evidence of patients taking part in the evaluation process. This has also been reported in a systematic review by Ree et al. [95] who looked specifically at patient involvement in person centeredness instruments for health professionals. This is painfully ironic. There is thus a further major lesson to be drawn from this study; that in developing the science of measurement of person-centred skills, new forms of partnership need to be formed between researchers and patients.

Conclusion

There are many instruments available which measure person-centred skills in healthcare practitioners and the most relevant and promising instruments that have already been developed, or items within them, should be further studied rigorously. Validation study of existing material is needed, not the development of new measures. New forms of partnership are needed between researchers and patients to accelerate the pace at which further work will be successful.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request, as are template data collection forms; data extracted from included studies; data used for all analyses; analytic code; any other materials used in the review not provided here.

Abbreviations

- COSMIN:

-

COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement Instruments

- STARD:

-

Modified Version of Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy

References

Håkansson Eklund J, Holmström IK, Kumlin T, Kaminsky E, Skoglund K, Höglander J, et al. “Same same or different?” A review of reviews of person-centered and patient-centered care. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(1):3–11.

Organization WH. WHO global strategy on people-centred and integrated health services. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Document Production Services; 2015 Available from: https://www.who.int/servicedeliverysafety/areas/people-centred-care/global-strategy/en.

D’Agostino TA, Bylund CL. The Nonverbal Accommodation Analysis System (NAAS): initial application and evaluation. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85(1):33–9.

Langberg EM, Dyhr L, Davidsen AS. Development of the concept of patient-centredness – a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(7):1228–36.

Naldemirci Ö, Wolf A, Elam M, Lydahl D, Moore L, Britten N. Deliberate and emergent strategies for implementing person-centred care: a qualitative interview study with researchers, professionals and patients. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):527.

Patel V, Buchanan H, Hui M, Patel P, Gupta P, Kinder A, et al. How do specialist trainee doctors acquire skills to practice patient-centred care? A qualitative exploration. BMJ Open. 2018;8(10):e022054.

Dwamena F, Holmes-Rovner M, Gaulden CM, Jorgenson S, Sadigh G, Sikorskii A, et al. Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD003267.

Hearn J, Dewji M, Stocker C, Simons G. Patient-centered medical education: a proposed definition. Med Teach. 2019;41(8):934–8.

Tzelepis F, Rose SK, Sanson-Fisher RW, Clinton-McHarg T, Carey ML, Paul CL. Are we missing the Institute of Medicine’s mark? A systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures assessing quality of patient-centred cancer care. BMC Cancer. 2014;14(1):41.

Dall’Oglio I, Mascolo R, Gawronski O, Tiozzo E, Portanova A, Ragni A, et al. A systematic review of instruments for assessing parent satisfaction with family-centred care in neonatal intensive care units. Acta Paediatr. 2018;107(3):391–402.

Baines R, Donovan J, Regan de Bere S, Archer J, Jones R. Patient and public involvement in the design, administration and evaluation of patient feedback tools, an example in psychiatry: a systematic review and critical interpretative synthesis. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2019;24(2):130–42.

Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(7):1087–110.

Kitson A, Marshall A, Bassett K, Zeitz K. What are the core elements of patient-centred care? A narrative review and synthesis of the literature from health policy, medicine and nursing. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(1):4–15.

Stewart M, Brown JB, Weston W, McWhinney IR, McWilliam CL, Freeman T. Patient-Centered Medicine: Transforming the Clinical Method. Boca Raton: CRC press, Taylor & Francis Group; 2013;332. 2013/12/28/

Stewart M, Brown JB, Weston W, McWhinney IR, McWilliam CL, Freeman TR. Patient-Centred Medicine: transforming the clinical method (2nd ed). Oxon: Radcliffe Medical Press; 2003;11(4).

Baker A. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. BMJ. 2001;323(7322):1192.

Terwee CB, Jansma EP, Riphagen II, de Vet HCW. Development of a methodological PubMed search filter for finding studies on measurement properties of measurement instruments. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(8):1115–23.

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1.

Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey CM, Holly C, Khalil H, Tungpunkom P. Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):132–40.

Koberich S, Farin E. A systematic review of instruments measuring patients’ perceptions of patient-centred nursing care. Nurs Inq. 2015;22(2):106–20.

Brouwers M, Rasenberg E, van Weel C, Laan R, van Weel-Baumgarten E. Assessing patient-centred communication in teaching: a systematic review of instruments. Med Educ. 2017;51(11):1103–17.

Hudon C, Fortin M, Haggerty JL, Lambert M, Poitras ME. Measuring patients’ perceptions of patient-centered care: a systematic review of tools for family medicine. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(2):155–64.

Ekman N, Taft C, Moons P, Mäkitalo Å, Boström E, Fors A. A state-of-the-art review of direct observation tools for assessing competency in person-centred care. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;109:103634.

Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic A. The STARD initiative. Lancet. 2003;361(9351):71. (London, England)

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL, et al. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(4):539–49.

Frankel R, Stein T. Getting the most out of the clinical encounter: the four habits model. J Med Pract Manag. 2001;16:184–91.

Krupat E, Frankel R, Stein T, Irish J. The four habits coding scheme: validation of an instrument to assess clinicians’ communication behavior. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;62(1):38–45.

Mjaaland TA, Finset A. Frequency of GP communication addressing the patient’s resources and coping strategies in medical interviews: a video-based observational study. BMC Fam Pract. 2009;10(1):49.

Margalit AP, Glick SM, Benbassat J, Cohen A, Margolis CZ. A practical assessment of physician biopsychosocial performance. Med Teach. 2007;29(8):e219–26.

Mercer SW, McConnachie A, Maxwell M, Heaney D, Watt GCM. Relevance and practical use of the Consultation and Relational Empathy (CARE) Measure in general practice. Fam Pract. 2005;22(3):328–34.

Mercer SW, Neumann M, Wirtz M, Fitzpatrick B, Vojt G. General practitioner empathy, patient enablement, and patient-reported outcomes in primary care in an area of high socio-economic deprivation in Scotland—a pilot prospective study using structural equation modeling. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73(2):240–5.

Witte LD, Schoot T, Proot I. Development of the client-centred care questionnaire. J Adv Nurs. 2006;56(1):62–8.

Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, Warner G, Moore M, Gould C, et al. Observational study of effect of patient centredness and positive approach on outcomes of general practice consultations. BMJ. 2001;323(7318):908–11.

Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, Warner G, Moore M, Gould C, et al. Preferences of patients for patient centred approach to consultation in primary care: observational study. BMJ. 2001;322(7284):468.

Smith F, Orrell M. Does the patient-centred approach help identify the needs of older people attending primary care? Age Ageing. 2007;36(6):628–31.

Lang F, McCord R, Harvill L, Anderson DS. Communication assessment using the common ground instrument: psychometric properties. Fam Med. 2004;36(3):189–98.

Gaugler JE, Hobday JV, Savik K. The CARES® Observational Tool: A valid and reliable instrument to assess person-centered dementia care. Geriatr Nurs. 2013;34(3):194–8.

Flocke SA. Measuring attributes of primary care: development of a new instrument. J Fam Pract. 1997;45(1):64–74.

Flocke SA, Stange KC, Zyzanski SJ. The Association of attributes of primary care with the delivery of clinical preventive services. Med Care. 1998;36(8):AS21–30.

Flocke SA, Orzano AJ, Selinger HA, Werner JJ, Vorel L, Nutting PA, et al. Does managed care restrictiveness affect the perceived quality of primary care? A report from ASPN. J Fam Pract. 1999;48(10):762–8.

Clayman ML, Makoul G, Harper MM, Koby DG, Williams AR. Development of a shared decision making coding system for analysis of patient–healthcare provider encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;88(3):367–72.

Bertakis KD, Azari R. Determinants and outcomes of patient-centered care. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85(1):46–52.

Ramsay J, Campbell JL, Schroter S, Green J, Roland M. The General Practice Assessment Survey (GPAS): tests of data quality and measurement properties. Fam Pract. 2000;17(5):372–9.

Jayasinghe UW, Proudfoot J, Holton C, Davies GP, Amoroso C, Bubner T, et al. Chronically ill Australians’ satisfaction with accessibility and patient-centredness. Int J Qual Health Care. 2008;20(2):105–14.

Henbest RJ, Stewart MA. Patient-centredness in the consultation .1: A method for measurement. Fam Pract. 1989;6(4):249–53.

Suhonen R, Välimäki M, Katajisto J. Developing and testing an instrument for the measurement of individual care. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32(5):1253–63.

Suhonen R, Leino-Kilpi H, Välimäki M. Development and psychometric properties of the Individualized Care Scale. J Eval Clin Pract. 2005;11(1):7–20.

Suhonen R, Schmidt LA, Katajisto J, Berg A, Idvall E, Kalafati M, et al. Cross-cultural validity of the Individualised Care Scale – a Rasch model analysis. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(5–6):648–60.

Petroz U, Kennedy D, Webster F, Nowak A. Patients’ perceptions of individualized care: evaluating psychometric properties and results of the individualized Care Scale. Can J Nurs Res Arch. 2011;43:80–100.

Acaroglu R, Suhonen R, Sendir M, Kaya H. Reliability and validity of Turkish version of the Individualised Care Scale. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20(1–2):136–45.

Suhonen R, Berg A, Idvall E, Kalafati M, Katajisto J, Land L, et al. Adapting the individualized care scale for cross-cultural comparison. Scand J Caring Sci. 2010;24(2):392–403.

Braddock CH, Fihn SD, Levinson W, Jonsen AR, Pearlman RA. How doctors and patients discuss routine clinical decisions. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(6):339–45.

Campbell C, Lockyer J, Laidlaw T, MacLeod H. Assessment of a matched-pair instrument to examine doctor−patient communication skills in practising doctors. Med Educ. 2007;41(2):123–9.

Stewart AL, Nápoles-Springer A, Pérez-Stable EJ. Interpersonal processes of care in diverse populations. Milbank Q. 1999;77(3):305–39.

Stewart AL, Nápoles-Springer AM, Gregorich SE, Santoyo-Olsson J. Interpersonal processes of care survey: patient-reported measures for diverse groups. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(3p1):1235–56.

Cope D, Schnabl GK, Hassard TH, Kopelow ML. The assessment of interpersonal skills using standardized patients. Acad Med. 1991;66(9):S34.

Cegala DJ, Coleman MT, Turner JW. The development and partial assessment of the medical communication competence scale. Health Commun. 1998;10(3):261–88.

Dong S, Butow PN, Costa DSJ, Dhillon HM, Shields CG. The influence of patient-centered communication during radiotherapy education sessions on post-consultation patient outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;95(3):305–12.

Smith MY, Winkel G, Egert J, Diaz-Wionczek M, DuHamel KN. Patient-physician communication in the context of persistent pain: validation of a modified version of the patients’ perceived involvement in care scale. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;32(1):71–81.

D’Agostino TA, Bylund CL. Nonverbal accommodation in health care communication. Health Commun. 2014;29(6):563–73.

Jenkins M, Thomas A. The assessment of general practitioner registrars’ consultations by a patient satisfaction questionnaire. Med Teach. 1996;18(4):347–50.

Radwin L, Alster K, Rubin K. Development and testing of the oncology patients’ perceptions of the quality of nursing care scale. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2003;30:283–90.

Suhonen R, Schmidt LA, Radwin L. Measuring individualized nursing care: assessment of reliability and validity of three scales. J Adv Nurs. 2007;59(1):77–85.

Can G, Akin S, Aydiner A, Ozdilli K, Durna Z. Evaluation of the effect of care given by nursing students on oncology patients’ satisfaction. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12(4):387–92.

Suhonen R, Välimäki M, Katajisto J, Leino-Kilpi H. Provision of individualised care improves hospital patient outcomes: an explanatory model using LISREL. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44(2):197–207.

Elwyn G, Edwards A, Wensing M, Hood K, Atwell C, Grol R. Shared decision making: developing the OPTION scale for measuring patient involvement. BMJ Qual Saf. 2003;12(2):93–9.

Zandbelt LC, Smets EMA, Oort FJ, de Haes HCJM. Coding patient-centred behaviour in the medical encounter. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(3):661–71.

Safran DG, Kosinski M, Tarlov AR, Rogers WH, Taira DA, Lieberman N, et al. The primary care assessment survey: tests of data quality and measurement performance. Med Care. 1998;36(5):728–39.

Safran DG, Karp M, Coltin K, Chang H, Li A, Ogren J, et al. Measuring patients’ experiences with individual primary care physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(1):13–21.

Duberstein P, Meldrum S, Fiscella K, Shields CG, Epstein RM. Influences on patients’ ratings of physicians: Physicians demographics and personality. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;65(2):270–4.

Shi L, Starfield B, Xu J. Validating the adult primary care assessment tool. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(2):161.

Haggerty JL, Pineault R, Beaulieu M-D, Brunelle Y, Gauthier J, Goulet F, et al. Practice features associated with patient-reported accessibility, continuity, and coordination of primary health care. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(2):116–23.

Chesser A, Reyes J, Woods NK, Williams K, Kraft R. Reliability in patient-centered observations of family physicians. Fam Med. 2013;45(6):428–32.

Schirmer JM, Mauksch L, Lang F, Marvel MK, Zoppi K, Epstein RM, et al. Assessing communication competence: a review of current tools. Fam Med. 2005;37(3):184–92.

Reinders ME, Blankenstein AH, Knol DL, de Vet HCW, van Marwijk HWJ. Validity aspects of the patient feedback questionnaire on consultation skills (PFC), a promising learning instrument in medical education. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76(2):202–6.

Lerman CE, Brody DS, Caputo GC, Smith DG, Lazaro CG, Wolfson HG. Patients’ perceived involvement in care scale: relationship to attitudes about illness and medical care. J Gen Intern Med. 1990;5(1):29–33.

Loh A, Simon D, Wills CE, Kriston L, Niebling W, Härter M. The effects of a shared decision-making intervention in primary care of depression: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67(3):324–32.

Sabee CM, Koenig CJ, Wingard L, Foster J, Chivers N, Olsher D, et al. The process of interactional sensitivity coding in health care: conceptually and operationally defining patient-centered communication. J Health Commun. 2015;20(7):773–82.

Mallinger JB, Griggs JJ, Shields CG. Patient-centered care and breast cancer survivors’ satisfaction with information. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;57(3):342–9.

Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, McWhinney IR, Oates J, Weston WW, et al. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(9):796–804.

Stewart M, Meredith L, Ryan B, Brown J. The patient perception of patient-centredness questionnaire (PPPC). London: Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry; 2004.

Haddad S, Potvin L, Roberge D, Pineault R, Remondin M. Patient perception of quality following a visit to a doctor in a primary care unit. Fam Pract. 2000;17(1):21–9.

Galassi JP, et al. The patient reactions assessment: a brief measure of the quality of the patient-provider medical relationship. Psychol Assess. 1992;4(3):346–51.

Engelberg R, Downey L, Curtis JR. Psychometric characteristics of a quality of communication questionnaire assessing communication about end-of-life care. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(5):1086–98.

Bieber C, Müller KG, Nicolai J, Hartmann M, Eich W. How does your doctor talk with you? Preliminary validation of a brief patient self-report questionnaire on the quality of physician-patient interaction. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2010;17(2):125–36.

Gallagher TJ, Hartung PJ, Gregory SW. Assessment of a measure of relational communication for doctor–patient interactions. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;45(3):211–8.

Shields CG, Franks P, Fiscella K, Meldrum S, Epstein RM. Rochester Participatory Decision-Making Scale (RPAD): reliability and validity. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(5):436–42.

Iramaneerat C, Myford CM, Yudkowsky R, Lowenstein T. Evaluating the effectiveness of rating instruments for a communication skills assessment of medical residents. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2009;14(4):575–94.

Smoliner A, Hantikainen V, Mayer H, Ponocny-Seliger E, Them C. Entwicklung und testtheoretische analyse eines Erhebungsinstruments zu Präferenzen und Erleben von Patienten in Bezug auf die Beteiligung an pflegerischen Entscheidungen im Akutspital. Pflege. 2009;22(6):401–9.

Paul-Savoie E, Bourgault P, Gosselin E, Potvin S, Lafrenaye S. Assessing patient-Centred care for chronic pain: validation of a new research paradigm. Pain Res Manage. 2015;20(4):183–8.

Silva d. Helping measure person-centred care: A review of evidence about commonly used approaches and tools used to help measure person-centred care. London: The Health Foundation; 2014.

Gärtner FR, Bomhof-Roordink H, Smith IP, Scholl I, Stiggelbout AM, Pieterse AH. The quality of instruments to assess the process of shared decision making: A systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(2): e0191747.

Louw JM, Marcus TS, Hugo J. How to measure person-centred practice – An analysis of reviews of the literature. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2020;12(1):e1–8.

Ree E, Wiig S, Manser T, Storm M. How is patient involvement measured in patient centeredness scales for health professionals? A systematic review of their measurement properties and content. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):12.

Acknowledgements

None

Preregistration

The protocol for this manuscript was not preregistered.

Funding

This study was funded by National Institute for Health Research—Research Capability Funding (RCF) in 20/21 for North East and North Cumbria and by the National Institute for Health Research [NIHR] PGfAR [RP-PG-0216–20002]. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. No funding bodies had any role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AD developed the concept and protocol and wrote the article. DS and JM contributed to concept and protocol development and reviewed and edited the article. JG searched the databases and reviewed the abstracts. AD and JM checked the full texts for eligibility. DS and AD did the quality assessment. All authors have read and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Search string for Embase, PsycInfo, MEDLINE. Search string for CINAHL.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

van Dongen, A., Stewart, D., Garry, J. et al. Measurement of person-centred consultation skills among healthcare practitioners: a systematic review of reviews of validation studies. BMC Med Educ 23, 211 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04184-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04184-6