Abstract

Background

Uganda continues to depend on a health system without a well-defined emergency response system. This is in the face of the rising cases of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest contributed largely to the high incidence of road traffic accidents. Non-communicable diseases are also on the rise further increasing the incidence of cardiac arrest. Medical students are key players in the bid to strengthen the health system which warrants an assessment of their knowledge and attitude towards BLS inclusion in their study curriculum.

Methods

A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted in 2021 among undergraduate medical students across eight public and private universities in Uganda. An online-based questionnaire was developed using Google forms and distributed via identified WhatsApp groups. Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test and logistic regression were performed in STATA 15 to assess the association between knowledge of BLS and demographics. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Out of the total 354 entries obtained, 351 were analyzed after eligibility screening. Of these, (n = 250, 71.2%) were male less than 25 years (n = 273, 77.8%). Less than half (n = 150, 42.7%) participants had undergone formal BLS training.

Less than a third of participants (n = 103, 29.3%) had good knowledge (≥ 50%) with an overall score of 42.3 ± 12.4%. Age (p = 0.045), level of academic progress (p = 0.001), and prior BLS training (p = 0.033) were associated with good knowledge. Participants with prior training were more likely to have more BLS knowledge (aOR: 1.7, 95% CI: 1.1–2.7, p = 0.009).

The majority (n = 348, 99.1%) believed that BLS was necessary and would wish (n = 343, 97.7%) to have it included in their curriculum.

Conclusions

Undergraduate medical students have poor BLS knowledge but understand its importance. Institutions need to adopt practical teaching methods such as clinical exposures, field experience in collaboration with local implementers, and participating in community health promotion campaigns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The provision of Basic Life Support (BLS) involves the recognition of sudden cardiac arrest followed by the activation of an emergency response system, early cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), and rapid defibrillation with an automated external defibrillator [1]. This can be provided by a health professional or any other trained bystander. Cardiac arrest is an increasingly common life-threatening event that accounts for more than 7 million deaths globally per year [2]. Common causes of cardiac arrest include cardiovascular diseases such as ischemic heart disease, cardiomyopathy, and valvular heart diseases among others accelerated by sedentary lifestyles, smoking, alcohol, and physical inactivity [3]. Trauma is another cause of cardiac arrest that cannot be over-emphasized especially in resource-limited countries where emergency response services are not well established [4, 5].

Uganda loses more than 35,000 individuals to road traffic accidents each year, largely due to delays in the initiation of BLS and transportation of victims to health facilities [6, 7]. Additionally, the lack of confidence in the provision of BLS contributed in part by lack of formal training and refresher courses, even in-hospital CPR is often delayed [8]. Reports indicate that only 18.4% of patients who suffered from a cardiac arrest in Mulago hospital received CPR [9]. This communicates a gap in the training programs that inadequately prepare health workers in emergency response. The heavy patient load owed to the alarmingly low doctor-patient ratio in Uganda may be another important factor explaining this deficit in health performance [10]. In the setting where there’s a paucity of trained bystanders, measures to better health professionals’ performance in the emergency care of patients must be taken meticulously. Such measures must be aimed at health system strengthening on both short- and long-term basis an example being goal-oriented medical training. This approach not only answers the question of competent health workers but also contributes to system strengthening by the provision of sufficient human resource necessary for training willing bystanders [11]. Some Universities such as Makerere University incorporate some aspects of first aid-BLS training in particular course units but knowledge of the practicability and retention of the information obtained from such training is not well studied. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the knowledge and attitude towards BLS among undergraduate medical students in Uganda to inform on the feasibility of the current medical schools’ curricula and how these can be improved to suit the country’s health care needs.

Methods

Study design and area

This was a cross-sectional quantitative study that targeted undergraduate medical students across eight public and private universities in Uganda from April to May 2021. The public universities include; Makerere University, Mbarara University of Science and Technology, Gulu University, Busitema University, and Kabale University. The private universities involved were; Kampala International University, Islamic University in Uganda, and King Caesar International University.

Study population

Undergraduate medical students undertaking Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery (MBChB), and other related courses including Bachelor of Nursing, Bachelor of Dental Surgery, Bachelor of Pharmacy at any of the aforementioned universities.

Selection criteria

All undergraduate medical students aged 18 years and above, enrolled in one of the above universities and undertaking the above-mentioned courses were eligible to participate in this survey. Being purely an online study, respondents without internet access were automatically excluded.

Sample size calculation

The sample size was calculated using Epi Info StatCalc for infinite population surveys. A 5% acceptable margin of error was considered; design effect of 1.0; cluster effect of 1.0, and a power of 80%, giving us an estimated sample size of 384 participants at a 95% confidence interval (95% CI). To cater for non-response associated with online surveys, 10% of the estimated sample size was added leading to a final sample size of 422 participants.

Sampling procedure and data collection

Uganda was in a partial lockdown at the time this study was conducted, with schools and higher institutions of learning using a blended physical and e-learning system to maximize social distancing. Because of this, we opted to use social media platforms such as WhatsApp Messenger® for enrolling eligible participants through contact persons identified at the different participating universities using a convenience sampling technique.

A questionnaire was developed using Part 3 of the 2015 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science guidelines [12]. A link to the Google form was sent to the potential participants via the identified WhatsApp groups and data collated. Sensitive details such as names, email addresses, registration numbers were not collected to ensure anonymity.

Data analysis

Data cleaning, coding, and marking were done using Microsoft Excel 2016 and exported to STATA® 15 for analysis. Demographic characteristics, knowledge, and attitude of the participants towards BLS were first summarized as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, and means for numerical variables. Knowledge score was calculated by awarding a point for every correct response to questions with a maximum score of 18 points. They were then converted to percentages. Knowledge was graded into good (≥ 50%) or poor knowledge (< 50%). Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test and binary logistic regression were performed to assess the association between knowledge on BLS and demographics. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of participants

A total of 354 entries were obtained out of which three were from ineligible courses and were excluded. Finally, 351 fully completed entries were cleaned and analyzed. Of the analyzed, (n = 250, 71.2%) were males and aged 25 years or less (n = 273, 77.8%). Most participants were undertaking MBChB (n = 301, 85.8%) mostly at a public university (n = 320, 91.2%). The distribution of participants in the different eligible universities in Uganda is shown in Fig. 1 Most of the participants were in clinical years of their training (n = 246, 70.1%). Only 150(42.7%) of the participants had undertaken BLS training before the study. Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of participants.

Distribution of participants across the different universities in Uganda. MAK: Makerere University, MUST: Mbarara University of Science and Technology, BU: Busitema University, KU: Kabale University, KCIU: King Caesar International University, KIU: Kampala International University, GU: Gulu University and IUIU: Islamic University in Uganda

Knowledge of basic life support

Of the 351 participants, less than a third (n = 103, 29.3%) had good knowledge regarding BLS (a score of > 50%). The mean knowledge score of all participants was 42.3% (SD = 12.4%). Participants above 25 years (46 vs. 41.2), MBChB students (42.9 vs. 38.4), Clinical students (43.6 vs. 39.2), and those with prior BLS training (44.7 vs. 40.4) had more mean scores compared to their counterparts.

At bivariate analysis, age (p = 0.045), level of academic progress (p = 0.001), and prior BLS training (p = 0.033) were significantly associated with good BLS knowledge. There was no association of university ownership (p = 0.650), sex (p = 0.541), or study program (p = 0.065) with BLS knowledge as shown in Table 2.

After adjusting for sex, university ownership, and level of academic progress, participants who had prior BLS training were more likely to be knowledgeable about BLS compared to those who had never received any formal training (OR: 1.7, 95% CI: 1.1–2.7, p = 0,018) as shown in Table 3.

Attitude towards Basic Life Support

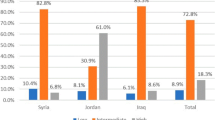

Overall, participants self-reported a good attitude towards BLS (Fig. 2). The majority of participants, either strongly agreed (n = 307, 87.5%) or agreed (n = 41, 11.7%) that BLS knowledge was a necessary skill; (n = 313, 89.2%) felt like they would voluntarily perform BLS on any victim who needed it while (n = 343, 97.7%) would wish to see BLS included within their study curriculum.

Discussion

In the current study, we found that the majority of students lacked knowledge regarding the provision of BLS despite recognizing its importance. Prior BLS training was a significant predictor of good knowledge.

Like in many other parts of the world, our study revealed poor BLS knowledge with a mean knowledge score of 42.3 ± 12.4%. In a related study conducted in Saudi Arabia among medical students, the overall mean knowledge score of 32.7% was reported [13]. However, in Ethiopia, Tsegaye et al., reported that the majority of their participants had good knowledge about CPR [14]. The probable explanation for the difference in results of their study and ours is that whereas we recruited students in the preclinical and clinical years, participants in the Ethiopian study were all in clinical years. Therefore, it is possible that they got training in basic life support as they advanced through medical training or rather participated in emergency response during their clinical rotations. This was also evidenced in our study by the differences in the mean knowledge scores between clinical and pre-clinical years (41.1 vs. 46.1). The proportion of participants with formal BLS training was very low in our study as it has been reported in many other countries [8, 14,15,16,17]. This training not only improves the BLS knowledge but is also associated with better practices among beneficiaries. This is especially important in Uganda’s health system where general practitioners (including intern doctors and medical officers) are the main primary caregivers let alone the limited number of critical care specialists [18]. This has been adopted by the developed countries as a way of reducing mortality associated with OHCA through upscaling the number of trained bystanders at any available opportunity [19,20,21]. In a study assessing CPR knowledge and attitude among secondary school students in Norway, it was reported that up to 335(89%) of participants had been trained to perform CPR, mostly from schools and a few by organizations like the Red Cross [22]. This gives their health system good backup as it is estimated that providing bystander CPR to a victim of cardiac arrest can reduce the rate of deterioration from 10% to just 3% per minute [23].

Although the current medical curriculum may contain some aspects of BLS, the role of this component need review to ensure the taught skills are understood and can be practiced when needed. BLS is a practical subject whose components cannot be fully exhausted in a classroom. This is because, although using this approach may provide knowledge to the students, without the real-time hands-on practice of the acquired skills, this knowledge is prone to be forgotten. Literature shows that 50% of skills learned after BLS training are lost in the subsequent two months [24]. This is especially true where regular practice and undertaking refresher courses are not possible [25,26,27,28,29]. In a study assessing CPR knowledge and skills among health professionals in Tanzania [8], it was reported that knowledge scores declined with working experience, and those who regularly performed CPR had better knowledge scores. Additionally, our study also shows that participants undertaking MBChB had more knowledge scores compared to other courses in the current study. This may be due to the false belief that doctors are responsible for handling emergencies that need BLS skills which creates an unnecessary gap in the health system’s capacity to provide on-site BLS services.

Many training approaches have been assessed to determine the most efficient but the most common challenge for all has been difficulties in knowledge and skills retention [30,31,32]. Among the studied, self-directed learning methods and traditional teaching methods have been reported to be effective at skilling trainees if well supported by refresher training to improve knowledge and skills retention [33]. These can be incorporated into the current students’ training curriculum to impart the desired knowledge and skills to trainees. Intending to upscale the trained bystanders and the quality of emergency response in the country, medical students by virtue of their training and exposure are more suitable candidates to set a pace to achieve this milestone. Fortunately, the current study as do many previous studies in other countries, show that medical students have an excellent attitude towards BLS and are more than willing to take on BLS training. Since they are more likely to have opportunities for practicing the acquired skill sets, an important aspect in knowledge retention, the frequency of required refresher training would be lower increasing the feasibility of this approach.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the knowledge and attitude of BLS among undergraduate medical students in Uganda. Findings from this study suggest the need to strengthen the current curriculum to accommodate more practical ways of teaching BLS among medical students. Information from this study, though focused on medical students, may also be used to revise curricula in other faculties as a way of increasing the prevalence of trained bystanders in the country.

Limitations

Being an online study conducted in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, data collection was only possible via online methods. Therefore, potential participants who did not have supporting gadgets, poor connectivity to the internet, or those who could not afford data costs for participating in this study were excluded. This might have led to selection bias which may limit the generalization of our study findings. Additionally, since the questionnaire was self-administered, there was a possibility of obtaining correct answers without a full understanding of the questions, recall bias and participants may have interpreted the questions differently.

Conclusions

We found that majority of undergraduate students in Uganda lack BLS knowledge and prior training was the most important factor significantly associated with better BLS knowledge. Regardless of this, participants had an excellent attitude towards BLS training and wished to have it integrated into their curriculum. Academic institutions under the stewardship of the National Council for Higher Education (NCHE) and Uganda Medical and Dental Practitioners’ Council (UMDPC) should aim to adopt more practical approaches to BLS training. These may include but are not limited to; (1) organizing clinical exposure sessions after theory sessions involving real-time patient management, (2) collaborating with local implementers such as the Red Cross and St. John’s Ambulance to give medical students the necessary hands-on experience in the field, and (3) engaging medical students in community health promotion campaigns where they are empowered to teach the general population basic CPR provision.

Finally, further studies should be conducted to determine the feasibility of integrating BLS in non-medical curricula. This would increase the number of trained providers available to initiate CPR in the community.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- aOR:

-

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- BLS:

-

Basic Life Support

- CPR:

-

Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation

- MBChB:

-

Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery

- NCHE:

-

National Council for Higher Education

- OHCA:

-

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest

- UMDPC:

-

Uganda Medical and Dental Practitioners’ Council

References

Irfan B, Zahid I, Khan MS, Khan OAA, Zaidi S, Awan S, et al. Current state of knowledge of basic life support in health professionals of the largest city in Pakistan: A cross-sectional study. BMC Health Services Research. 2019;19(1):1–7.

Ali A Sovari AGK. Sudden Cardiac Death. MedScape. 2020. Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/151907-overview. cited 2021 Feb 4.

Maron BJ, Gardin JM, Flack JM, Gidding SS, Kurosaki TT, Bild DE. Prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a general population of young adults: Echocardiographic analysis of 4111 subjects in the CARDIA study. Circulation. 1995;92(4):785–9.

Mawani M, Kadir M, Azam I, Razzak JA. Characteristics of traumatic out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients presenting to major centers in Karachi, Pakistan - A longitudinal cohort study. International Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2018;11(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-018-0214-7. Available from: https://intjem.biomedcentral.com/articles/. cited 2022 Jan 22.

Ocen D, Kalungi S, Ejoku J, Luggya T, Wabule A, Tumukunde J, et al. Prevalence, outcomes and factors associated with adult in hospital cardiac arrests in a low-income country tertiary hospital: a prospective observational study. BMC Emerg Med. 2015;15(1). Available from: http://www.pmc.com/articles/PMC4574081/. cited 2022 Jan 28.

Andrews C, Kobusingye O, Lett R. Road traffic accident injuries in Kampala. East Afr Med J. 1999;76:189–94.

Muni K, Ningwa A, Osuret J, Bayiga E, Namatovu S, Biribawa C, et al. Estimating the burden of road traffic crashes in Uganda using police and health sector data sources. Injury Prevention. 2020;injuryprev-2020.

Kaihula WT, Sawe HR, Runyon MS, Murray BL. Assessment of cardiopulmonary resuscitation knowledge and skills among healthcare providers at an urban tertiary referral hospital in Tanzania. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30514275/. cited 2021 Jul 1.

Ocen D, Kalungi S, Ejoku J, Luggya T, Wabule A, Tumukunde J, et al. Prevalence, outcomes and factors associated with adult in hospital cardiac arrests in a low-income country tertiary hospital: a prospective observational study. BMC emergency medicine. 2015;15:23.

Wabulyu J. The state of Patient safety in Uganda. International Society for Quality in Health Care brief. 2019. Available from: https://isqua.org/world-patient-safety-day-blogs/the-state-of-patient-safety-in-uganda.html. cited 2021 Oct 20.

Altintaş KH, Aslan D, Yildiz AN, Subaşi N, Elçin M, Odabaşi O, et al. The evaluation of first aid and basic life support training for the first year university students. Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2005;205(2):157–69.

Travers AH, Perkins GD, Berg RA, Castren M, Considine J, Escalante R, et al. Part 3: Adult basic life support and automated external defibrillation: 2015 international consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations. Circulation. 2015;132:S51–83.

Al-Mohaissen MA. Knowledge and attitudes towards basic life support among health students at a Saudi women’s university. Sultan Qaboos University Med J. 2017;17(1):e59-65.

Tsegaye W, Tesfaye M, Alemu M. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Associated Factors in Ethiopian University Medical Students. J en Pract. 2015;3:206.

Mani G, Annadurai K, Danasekaran R, Ramasamy JD. A cross-sectional study to assess knowledge and attitudes related to Basic Life Support among undergraduate medical students in Tamil Nadu, India. Vol. 4, No1 KAP on BLS among medical students. Uniwersytet Medyczny w Białymstoku; 2014.

Mohammed Z, Arafa A, Saleh Y, Dardir M, Taha A, Shaban H, et al. Knowledge of and attitudes towards cardiopulmonary resuscitation among junior doctors and medical students in Upper Egypt: Cross-sectional study. International J Emergency Med. 2020.

Adewale BA, Aigbonoga DE, Akintayo AD, Aremu PS, Azeez OA, Olawuwo SD, et al. Awareness and attitude of final year students towards the learning and practice of cardiopulmonary resuscitation at the University of Ibadan in Nigeria. African J Emergency Med. 2021;11(1):182–7.

Atumanya P, Sendagire C, Wabule A, Mukisa J, Ssemogerere L, Kwizera A, et al. Assessment of the current capacity of intensive care units in Uganda; A descriptive study. J Critical Care. 2020;55:95–9.

Chan PS, McNally B, Tang F, Kellermann A. Recent trends in survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in the United States. Circulation. 2014;130(21):1876–82.

Nichol G, Thomas E, Callaway C, Jama JH. Undefined. Regional variation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest incidence and outcome. 2008. http://www.jamanetwork.com/.

Wissenberg M, Lippert F, Folke F, Jama PW. Undefined. Association of national initiatives to improve cardiac arrest management with rates of bystander intervention and patient survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. 2013. http://www.jamanetwork.com/.

Kanstad BK, Nilsen SA, Fredriksen K. CPR knowledge and attitude to performing bystander CPR among secondary school students in Norway. Resuscitation. 2011;82(8):1053–9.

Ibrahim WH. Recent advances and controversies in adult cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Postgraduate Med J. 2007;83(984):649–54.

McKENNA SP, GLENDON AI. Occupational first aid training: Decay in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) skills. Journal of Occupational Psychology. 1985.;58(2):109–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1985.tb00186.x. Available from: https://bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/. cited 2021 Jul 1.

Soar J, Mancini ME, Bhanji F, Billi JE, Dennett J, Finn J, et al. Part 12: Education, implementation, and teams: 2010 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science with Treatment Recommendations. Resuscitation. 2010;81 Suppl 1(1):e288–330. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20956038.

García-Suárez M, Méndez-Martínez C, Martínez-Isasi S, Gómez-Salgado J, Fernández-García D. Basic Life Support Training Methods for Health Science Students: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(5). Available from: http://www.pmc.com/articles/PMC6427599/. cited 2021 Oct 17.

N M, B DW, N C, J R, T L, L H, et al. Repetitive sessions of formative self-testing to refresh CPR skills: a randomised non-inferiority trial. Resuscitation. 2014;85(9):1282–6. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24983199/. cited 2021 Oct 17.

W S, K A, C L, N D, I D, K D. Retention of Basic-Life-Support Knowledge and Skills in Second-Year Medical Students. Open access emergency medicine: OAEM. 2020;12:211–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33061682/. cited 2021 Oct 17.

F S, L S, EL C. Retention of CPR performance in anaesthetists. Resuscitation. 2006;68(1):101–8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16325986/. cited 2021 Oct 17.

Aa A, Mm A. High-fidelity simulation effects on CPR knowledge, skills, acquisition, and retention in nursing students. Worldviews Evidence-Based Nurs. 2014;11(6):394–400.

LP R, R H, P P, J W, B C, R M, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing traditional training in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) to self-directed CPR learning in first year medical students: The two-person CPR study. Resuscitation. 2011;82(3):319–25.

I B, A R-B, JM G-G, J O, V C, M S. Using a serious game to complement CPR instruction in a nurse faculty. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2015;122(2):282–91.

Cason CL, Kardong-Edgren S, Cazzell M, Behan D, Mancini ME. Innovations in basic life support education for healthcare providers: Improving competence in cardiopulmonary resuscitation through self-directed learning. J Nurs Staff Dev. 2009;25(3):E1–13.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to appreciate Prof. Sarah Kiguli the PI of the Health-Professional Education Partnership Initiative (HEPI) for leading away in developing undergraduate research in Uganda through mentorship and financial support. We commend the following students for assisting us in data collection: Victor Niwamanyire, Faridah Ainembabazi, Hilda Koriang, Patricia Kulwenza, Khushi Dhawan, Annet Karungi, Reagan Kakande, Patience Philomena Idro Anzoa, Misba Noori, and Melody Mercy Arindagye. In the same spirit, we appreciate all medical students in Uganda who spared their time to participate in this study amidst all the current challenges.

Funding

This study was not funded.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NS conceptualized the idea. NS, GW, AI, and PM developed the study tools. NS, GW, AI, PM, AMK, GN, NKW, WZ, LK, JK jointly participated in the data collection process. NS, AI, and GW prepared the first draft of the manuscript. AMK, JK, TSL, and AT provided extensive comments on the first draft and contributed to developing the final draft. All authors reviewed the final draft and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki; approved by the Mulago Hospital Research and Ethics Committee under reference number MHREC 2051. Informed consent was obtained from all participants and the study was anonymous.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ssewante, N., Wekha, G., Iradukunda, A. et al. Basic life support, a necessary inclusion in the medical curriculum: a cross-sectional survey of knowledge and attitude in Uganda. BMC Med Educ 22, 140 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03206-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03206-z