Abstract

Background

Midwives are the key skilled birth attendants in Afghanistan. Rapid assessment of public and private midwifery education schools was conducted in 2017 to examine compliance with national educational standards. The aim was to assess midwifery education to inform Afghanistan Nurses and Midwives Council and other stakeholders on priorities for improving quality of midwifery education.

Methods

A cross-sectional assessment of midwifery schools was conducted from September 12–December 17, 2017. The Midwifery Education Rapid Assessment Tool was used to assess 29 midwifery programs related to infrastructure, management, teachers, preceptors, clinical practice sites, curriculum and students. A purposive sample of six Institute of Health Sciences schools, seven Community Midwifery Education schools and 16 private midwifery schools was used. Participants were midwifery school staff, students and clinical preceptors.

Results

Libraries were available in 28/29 (97%) schools, active skills labs in 20/29 (69%), childbirth simulators in 17/29 (59%) and newborn resuscitation models in 28/29 (97%). School managers were midwives in 21/29 (72%) schools. Median numbers of students per teacher and students per preceptor were 8 (range 2–50) and 6 (range 2–20). There were insufficient numbers of teachers practicing midwifery (132/163; 81%), trained in teaching skills (113/163; 69%) and trained in emergency obstetric and newborn care (88/163; 54%). There was an average of 13 students at clinical sites in each shift. Students managed an average of 15 births independently during their training, while 40 births are required. Twenty-four percent (7/29) of schools used the national 2015 curriculum alone or combined with an older one. Ninety-one percent (633/697) of students reported access to clinical sites and skills labs. Students mentioned, however, insufficient clinical practice due to low case-loads in clinical sites, lack of education materials, transport facilities and disrespect from school teachers, preceptors and clinical site providers as challenges.

Conclusions

Positive findings included availability of required infrastructure, amenities, approved curricula in 7 of the 29 midwifery schools, appropriate clinical sites and students’ commitment to work as midwives upon graduation. Gaps identified were use of different often outdated curricula, inadequate clinical practice, underqualified teachers and preceptors and failure to graduate all students with sufficient skills such as independently having supported 40 births.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Afghanistan has come a long way in reducing the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) from 1600 in 2002 to 638 per 100,000 live births in 2019 [1, 2]. Female clinicians (midwives, female doctors and obstetrician &gynecologists) were present in only 138 (18%) of the 783 public health facilities However, Package of Health Services (BPHS) with 1075 health facilities in 2004 and 1829 in 2011 [3]. MoPH invested in educating competent midwives with the essential range of skills and recruited them to increase the numbers of skilled birth attendants (SBA) since early 2003 [4]. This included strengthening of 2 years’ diploma midwifery education programs through the existing Institute of Health Sciences (IHS) and establishing community midwifery education (CME) programs, all compliant with the International Confederation of Midwives (ICM)’ recommendations on core competencies in midwifery [5]. The schools were funded by MoPH, and several bilateral and multilateral international non-governmental organizations (NGOs). The number of midwives working in Afghanistan was only 467 in 2002 and this number increased to 7244 in 2019 [6, 7]. Private schools graduated 25,177 midwives during the period from 2009 to 2019 [8]. There are, however, no reliable data about the employment status of the midwives graduated from private schools. With a crude birth rate of 35 per 1000 persons or 1.2 million children born per year in Afghanistan (total population 32.2 million) and at a rate of 4.45 SBA per 1000 as recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO), the number of midwives may look sufficient nowadays [9,10,11]. Midwives’ availability, however, was 16.7% in public facilities in Southeastern provinces as compared to 63.6% in Northeastern provinces indicating inequity in their distribution [12]. Although, broader health system, socio-cultural and security issues are important, high quality midwifery education remains nevertheless crucial to addressing people’s access to midwifery care in Afghanistan [13].

MoPH developed a national accreditation policy based on educational standards and established the Afghanistan Midwifery and Nursing Education Accreditation Board (AMNEAB) in 2005 [14]. An evaluation of public midwifery schools in 2008 identified areas of strengthening midwifery programs as ICM and MoPH recommended and followed by establishment of a national 2 years’ curriculum for IHS and CME programs [15]. Competency building, effective preceptorship, simulated and clinical practice, however, remained poorly documented [16].

A systematic evaluation of midwifery education has not been carried out to examine its various dimensions. Midwifery education became a priority for assessment with the support of MoPH, donors such as the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), AMA and other partner organizations as part of the USAID-funded project HEMAYAT. This paper is the result of a rapid assessment of public and private midwifery schools in the end of 2017, conducted in collaboration with Jhpiego, AMA, MoPH, in a time that efforts were at its peak to establish the Afghanistan Nurses and Midwives Council (ANMC) with the mandate to assure high quality preservice education for midwives [17]. The objective of the study was to examine public and private school educational standards for infrastructure and management, numbers and competencies of teachers and preceptors, clinical practice sites, curriculum and numbers of students per class. Findings will help stakeholders to inform future policies and practices towards improved quality of midwifery education in Afghanistan.

Methods

Research design

We conducted a cross-sectional assessment of public and private midwifery schools from September to December 2017. The Midwifery Education Rapid Assessment Tool developed by Jhpiego was adapted for use in Afghanistan and included interview tools for school managers, teachers and preceptors, a self-administered questionnaire for midwifery students and a clinical practice site observation form. Tools were pre-tested in two private schools in Kabul in August 2017 [18]. This tool, based on ICM’s educational standards, was designed to assess five areas of pre-service midwifery education: infrastructure and management, teachers and preceptors, clinical practice sites, curriculum and students. Review of school records and documents, interviews and observation of school and clinical practice facilities were the research methods used . The study was approved by both Institutional Review Boards of the Afghan Public Health Institute and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Setting

Afghanistan had eight IHS, one direct-entry bachelor’s degree midwifery program, implemented by Kabul Medical University (KMU) (also treated as IHS in this assessment), 24 CME and 124 private midwifery schools at the time of assessment (Fig. 1). IHS midwifery schools accept 12th grade school students through a yearly entry course examination and provide a 2 years’ diploma curriculum for midwives to serve primarily in large clinical and hospital settings after graduation. The KMU program also accepts students through concourse and provides a 4 years bachelor’s curriculum. CME schools accept candidates from communities, selected through a community dialogue from the eligible school graduate girls and women in special CME schools located in provinces. Graduates of CMEs are bound by a commitment and community guarantee to work at least 2 years in primary health care clinics, designated at the start of the training. However, CME graduates are also able to work in larger clinics and hospitals. Private schools in this assessment implement 2 years’ midwifery diploma programs.

Schools were purposively selected from five large population provinces, namely Kabul, Balkh, Herat, Nangarhar and Kandahar to reflect school type and funding sources. The five IHS from these provinces with KMU were included (total 6 IHS). One CME from Kabul, Herat and Kandahar were included, but Balkh and Nangarhar provinces did not have CME-schools, therefore, the nearest CME programs (i.e. Baghlan instead of Balkh and Laghman instead of Nangarhar) were selected. As all schools were supported either by the government or by USAID, two CME schools funded by other donors, both in Faryab province, were also included (total 7). Due to accessibility and security constraints in the five focus provinces, only 23 out of 124 private schools could be contacted, out of which 16 agreed to participate in the study. Sampling was nonrandom, and no statistical testing was intended.

Data collection

Data collectors were ten Jhpiego Provincial Midwifery Officers and four members of the Afghan Midwives Association (AMA), all female midwives. They were trained to use data collection tools, research methodology and ethics for 5 days. Teams of 2–3 data collectors visited each school for 2 days from September–December 2017. They reviewed register books and school records, visited a maximum of three on-going classes, visited clinical practice sites and conducted interviews with target participants. The assessment team monitored the data collectors in the field and data were checked for consistency. Jhpiego’s Monitoring Evaluation and Research Manager conducted interviews with school managers, teachers and clinical preceptors. Data collectors asked students to fill in self-administered questionnaires. They observed school premises and school records, student logbooks and clinical registers to confirm data on infrastructure, management, curriculum and equipment.

Analysis

Two members of the team entered and cleaned quantitative data in a Microsoft Excel database, transferred to STATA IC 15 for analysis. The assessment team lead completed quantitative analysis including calculation of counts, percentages, means and standard errors, medians and ranges for different school and health facility types. Preliminary findings of the survey were presented by the research team to school representatives and key stakeholders led by the MoPH in a validation workshop in March 2018.

Results

Seven CME, six IHS (including the KMU bachelor program) and 16 private schools were assessed. Median number of years of activity was 7.6 (range 1.7–12) for CME, 39.5 (range 3.8–45.9) for IHS and 5.8 for private schools (range 1.6–10.8). The KMU program had been in operation for 4 years, but had not graduated any student at the time of assessment. Median number of students ever graduated from the selected schools was 67 for CME (range 25–106) and 406 for IHS (range 251–692); numbers of students graduated from private schools were unavailable.

The assessment identified gaps in infrastructure, availability and preparedness of the teachers and preceptors, students’ access to clinical sites and practical work in relation with caseloads and inconsistencies in curricula in the different schools.

Infrastructure, equipment and management

More than 90% (26–28/29) of the schools had rooms for classes, desks for every student, classrooms with good ventilation and lights and unobstructed views for students. All schools accommodated no more than 30 students in one room. Fourteen out of 29 schools (48%) met all six classroom criteria (Table 1). While 28 (97%) schools had a library, only four (14%) had all nine recommended books (supplementary file 1). All schools reported having skills labs, which were actually open for students at the time of assessment in 20 (69%) and 22 (76%) had full-time skills lab managers. Childbirth simulators were available in 17 (59%) schools and all except one private school had newborn resuscitation models. Midwives served as managers in 21 (72%) schools and 22 (76%) managers had experience in midwifery, including one doctor who had been a midwife in the past (Table 1).

Teachers and clinical preceptors

Observational visits to one, two or three ongoing classrooms were conducted when available. In these visits, median number of students per teacher was 8.3 (range 1.8–50) and students per preceptor was 6 (range 1.5–20). All IHS schools assigned specific personnel as clinical preceptors, while 6/7 (86%) CME schools and 11/16 (69%) private schools did so (Table 2).

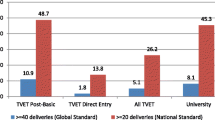

The assessment team conducted interviews with 163 teachers. From this group, 132 (81%) had practiced midwifery and 150 (92%) had previous teaching experience. In total, 95 (58%) teachers had been practicing midwifery for at least 2 years. Of 163 teachers, 113 (69%) had been trained in teaching skills and 88 (54%) in emergency obstetric and newborn care. Student-to-teacher and student-to-preceptor ratios per school type are shown in Fig. 2.

A subgroup of 58 out of 163 (36%) teachers were willing to discuss their teaching practices with none of them reporting use of role-play as a teaching method. In addition, 51 clinical preceptors were assigned to the selected schools with 25 (49%) having no other parallel assignments in clinics and 41 (80%) preceptors received coaching from school teachers (Table 3).

Clinical sites

Schools had agreements with between one and 15 health facilities (median 3) serving as clinical practice sites for their students. The standard of assisting 40 uncomplicated births for graduation was mentioned in 16/29 (55%) schools. Median number of births recorded as independently practiced, was 40 births (range 0–70) per student (Table 4).

For each school, one facility used as clinical site was selected including one basic health center, five comprehensive health centers, five provincial hospitals, 11 private health facilities, five regional hospitals and two specialized hospitals. These 29 facilities reported 90,297 uncomplicated births in the past 6 months. On average, 13 students were accommodated in 8 h working shifts in these facilities.

In a subset of 20 (69%) clinical sites facilities, data collectors were also allowed to review student logbooks showing that students assisted on average 14.6 births with the highest average of 40 for two SH. In this subgroup, preceptors in 4/20 (20%) health facilities (2 PH and 2 SH) declared that completing assistance of 40 births is enforced for graduation (Table 5).

Curriculum

Different editions of midwifery curricula were in use in the schools including IHS 2006 midwifery curriculum, IHS 2010 midwifery curriculum, CME 2010 midwifery curriculum and national 2015 midwifery curriculum. Two (13%) private schools were using their own customized curriculum. Seven (24%) schools were using the national 2015 midwifery curriculum among which one IHS used IHS 2010 and one private school also used IHS 2006 complementary. Five (71%) CMEs used CME 2010 curriculum, while 13 (45%) schools including one CME used IHS 2010 curriculum. One (17%) private school used IHS 2006 and KMU Bachelor program had its own curriculum.

Teaching materials for curriculum implementation were provided by MoPH for 27 schools, while the KMU Bachelor program and one private school developed their own learning materials.

Students

Self-administered questionnaires were given to 697 students from 28 schools. One CME school declined to participate. Access to clinical sites was reported by 633 (91%) students, access to skills labs by 631 (91%) and access to computer labs by 457 (66%). Barriers cited by students were lack of access to health facilities, low caseload, lack of equipment and supplies, insufficient number of preceptors and being neglected by the teachers and preceptors tending to prioritize other clinical and administrative duties. All 116 CME students said they will work as midwives upon graduation; while 117 of 131 IHS students (89%) and 384 of 450 private school students (85%) stated such intention (Table 6).

Discussion

Our findings indicate that public and private midwifery schools are preparing midwives with mixed results. Some expectations are met by the programs in different areas. Specifically, classrooms, skills labs and clinical practice sites of most schools had the required infrastructure, equipment and supplies. The majority of schools used one of the once-approved versions of the curricula, though some were outdated. Midwives were in leading positions in most schools and most teachers had experience in midwifery or management. Students, especially in CME schools, reported feeling safe and secure in their schools and were determined to work as midwives in the future. This is encouraging in the light of findings of a study in 11 provinces showing employment rates for CME graduates from 28.4% (in Khost province) to 84.3% (in Herat province) [19]. Recruitment into CME programs is aligned with a health workforce approach to encourage retention and commitment to serve their own communities. Several shortcomings, however, were identified by that study including inadequate resources and incompetence of the teachers and preceptors. Midwives may graduate from these schools without meeting certain global or national competency requirements and the ability to perform life-saving interventions with confidence as mandated by ICM [20].

Shortages of learning materials, teachers and preceptors and overburdened clinical sites were identified in several schools, while low caseloads in smaller facilities were also observed. Number of students per teacher varied largely and was as high as 50 in one school. One teacher per 45 students has also been observed in other low-income countries [21]. Shortage of teachers can deprive students of support and interaction and compromises quality education. Some schools with higher numbers of teachers may have many part-time teachers serving in different schools. This may affect the level of attachment to specific cohorts of students and compromises commitment and accountability for competency building of students. Knowing that optimizing teacher-student ratios requires additional investment, ANMC and MoPH should ensure such investments are made. Some schools in Afghanistan tried to employ new graduates to fill these gaps with rather unexperienced teachers [22]. MoPH and ANMC, however, have to verify that schools are established with sufficient numbers of competent teachers and preceptors and advocate to focus on quality and quantity of faculty per standards. Only then is Afghanistan in a better position to meet Sustainable Development Goal 3 to improve maternal and newborn health, as emphasized by Strengthening Quality Midwifery Education for Universal Health Coverage in 2030 [23].

Competencies of teachers and preceptors were questionable with many of them having no training in evidence-based clinical and teaching methodologies, lecturing in a traditional way instead of more interactive student-centered methods. Poor teaching and clinical skills of midwifery faculties and preceptors are commonly found in low- and middle-income countries as was shown in Ethiopia by documented dissatisfaction of students [24]. Regular capacity assessments and continuing education are required to keep teachers up-to-date with standards and evidence-based clinical practices [25]. ANMC should monitor the maximum number of students per teacher and preceptor and require schools to demonstrate their investments in continued education of their faculties [26].

Complacency with achieving ICM competencies will lead to less educated midwives who are not able to provide high-quality care [27]. The 2015 national midwifery curriculum requires students to independently perform 40 births to become competent and competency-based education is the basis of midwifery education in Afghanistan [28]. A review of 73 countries showed that more than 30 births assisted by students occurred in 32 (44%) of them, implying similar constraints globally [29]. ANMC are in a unique position as they established regulatory systems to learn from experiences of other countries in ensuring midwives to be competent at graduation. All necessary elements of high-quality midwifery care must be taught, balancing theory and practice to produce fully competent midwives upon graduation [30].

Midwifery care is cost-effective, affordable and sustainable. It has contributed to improvement of maternal and newborn health [31, 32]. Midwifery reduces maternal and newborn deaths and stillbirths, strengthens economic activity and ripples favorably across macroeconomics, provides women with decent work and results in economic stabilization in society [33]. Specifically, midwifery leads to better health outcomes. Insufficient monitoring of midwifery education is recognized by the global community as a major area of concern [23]. In Afghanistan, midwifery education was not explicitly mentioned among high-priority areas in the 2011 draft national policy on nursing and midwifery [34]. Due to lack of strong positive and direct language in the policy it is difficult to encourage clinical facilities to willingly and enthusiastically accommodate learning opportunities for student-midwives.

Clinical sites, often independent of the schools, do not bear the responsibility of providing sufficient clinical work for students [35]. On the other hand, clinical sites face challenges with simultaneously competing students, human resource constraints and lack of professional preceptors [36]. Congestion of students seeking practice opportunities in a single health facility makes it difficult to expose them to adequate case-load [37]. It is important to clarify that midwifery schools are accountable for ensuring clinical practice opportunities of adequate quality and competency building of their students [38]. The standards of 40 births attended by students was not consistently met; for comparison a third of midwifery students in Ethiopia met their standard of only 20 births [24]. Caseloads in many hospitals are high and it is achievable in Afghanistan to ensure students attend 40 births. It needs, however, commitment to students working 24/7 and improved coordination of student placements. These issues can be addressed by ANMC through revised accreditation processes and addressing socio-cultural barriers.

Inconsistency of curricula in different schools is a chronic issue with only five among the nine IHS schools using the latest curriculum in 2011 [39]. The now obsolete 18-months CME 2010 curriculum inadvertently resulted in the misconception that CME graduates are less qualified than IHS ones. Schools should implement the latest national standard curriculum, and ANMC and MoPH should establish verifiable routines and information management systems to monitor and mitigate any deviations [5]. In Afghanistan, where SBAs include midwives, obstetricians and female general practitioners trained in Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care (EmONC), midwives are more evenly distributed geographically among all SBAs, and provide 42% of all maternal and newborn healthcare [10, 12]. Competency-based midwifery education with adequate clinical practice is required for producing a competent workforce [40]. Midwives want better education, including access to higher education and development, to be empowered to support quality, equity and dignity as healthcare priorities [41].

Limitations

This study was a rapid assessment conducted in purposively selected midwifery schools. Only a fraction of all private schools could, however, participate. Very few students who reported lack of access to some facilities, dared to mention access barriers indicating biased responses in favor of the schools. Very few schools were willing to share logbooks of their students. Therefore, caution is advised in generalizing the findings, especially those of private midwifery schools. The study was implemented at the end of 2017 and the findings were presented in several occasions to MoPH, AMA and other part ners in 2018 and were actively used for improvement of midwifery education. Specifically, the findings were used to expedite establishment of ANMC. However, the authors believe that the Afghan experience presented in this manuscript will still provide valuable insights. They will also provide a point of departure for any future study into the state of midwifery in Afghanistan.

Conclusion

Strong competent midwives have the potential to transform and improve the quality of maternity care for strengthening reproductive, maternal and neonatal health in Afghanistan as well as to contribute to building a resilient health system. MoPH and ANMC need to prioritize and prepare an action plan to strengthen high-quality midwifery education and make strategic decisions on midwifery education, its management and compliance with educational standards through accreditation and enabling educational environments.

Availability of data and materials

The corresponding author is willing to provide the data on request.

Abbreviations

- AHS:

-

Afghanistan Health Survey

- AMA:

-

Afghan Midwives Association

- AMNEAB:

-

Afghanistan Midwifery and Nursing Education Accreditation Board

- ANMC:

-

Afghanistan Nurses and Midwives Council

- BPHS:

-

Basic Package of Health Services

- CME:

-

Community Midwifery Education

- EmONC:

-

Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care

- EPHS:

-

Essential Package of Hospital Services

- GDHR:

-

General Directorate of Human Resources

- ICM:

-

International Confederation of Midwives

- IHS:

-

Institute of Health Sciences

- KMU:

-

Kabul Medical University

- MMR:

-

Maternal mortality ratio

- MoPH:

-

Afghanistan Ministry of Public Health

- NSIA:

-

National Statistics and Information Authority.

- SBA:

-

Skilled Birth Attendants

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Bartlett L, Mawji S, Whitehead S, et al. Where giving birth is a forecast of death: maternal mortality in four districts of Afghanistan, 1999–2002. Lancet. 2005;365:864–70.

UNFPA, WHO, UNICEF, World Bank Group, United Nations Population Division. Trends in maternal mortality: 2000 to 2017. New York City: UNFPA; 2019.

Newbrander William, Ickx Paul. Ferozuddin Feroz & Hedayatullah Stanekzai Afghanistan’s Basic Package of Health Services: Its development and effects on rebuilding the health system. Global Public Health. 2014;9(sup1):S6–28.

Currie Sheena, Azfar Pashtoon, Fowler Rebecca C. A bold new beginning for midwifery in Afghanistan. Midwifery. 2007;23:226–34.

Speakman EM, Shafi A, Sondorp E, Atta N, Howard N. Development of the Community Midwifery Education initiative and its influence on women’s health and empowerment in Afghanistan: a case study. BMC Women’s Health. 2014;14:111.

Afghanistan Ministry of Public Health, MSH, HANDS, MSH/Europe, USAID, European Commission, United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), Japan International Cooperation Agency. National Health Resources Assessment 2002. Kabul, Afghanistan: MoPH; 2002.

Afghanistan Midwifery and Nursing Education Accreditation Board. Afghanistan Midwifery and Nursing Education Accreditation Board dataset. Accessed July 27 2019.

Data shared by Ministry of Public Health, General Directorate of Human Resources. Directorate of Private Institutes. (Single source, not verified independently).

National Statistics and Information Authority (NSIA). Population 1398. URL: https://www.nsia.gov.af:8080/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/%D8%A8%D8%B1-%D8%A2%D9%88%D8%B1%D8%AF-%D9%86%D9%81%D9%88%D8%B3-%DA%A9%D8%B4%D9%88%D8%B1-%D8%B3%D8%A7%D9%84-1398.pdf (last accessed March 18 2020).

Royal Tropical Institute (KIT). Afghanistan Health Survey 2018. Amsterdam: KIT; 2019.

World Health Organization. 2016. Health workforce requirements for universal health coverage and the Sustainable Development Goals. (Human Resources for Health Observer, 17). ISBN 978 92 4 151140 7.

Faqir M, Zainullah P, Tappis H, et al. Availability and distribution of human resources for provision of comprehensive emergency obstetric and newborn care in Afghanistan: a cross-sectional study. Confl Heal. 2015;9:9.

Sachiko Miyake, Elizabeth M Speakman, Sheena Currie and Natasha Howard. Community midwifery initiatives in fragile and conflict-affected countries: a scoping review of approaches from recruitment to retention. Health Policy Planning, 2017, Vol. 32, No. 1.

Afghanistan Ministry of Public Health (MoPH). National Policy on Midwifery education and the accreditation of Midwifery education programs in Afghanistan. Afghanistan: Kabul; 2005.

Zainullah P, Ansari N, Yari K, et al. Establishing midwifery in low-resource settings: guidance from a mixed-methods evaluation of the Afghanistan midwifery education program. Midwifery. 2014;30:1056–62.

Johnson P, Fogarty L, Fullerton J, Bluestone J, Drake M. An integrative review and evidence-based conceptual model of the essential components of pre-service education. Hum Resour Health. 2013;11(1):42.

Jafari M, Currie S, Qarani WM, Azimi MD, Manalai P, Zyaee P. Challenges and facilitators to the establishment of a midwifery and nursing council in Afghanistan. Midwifery. 2019;75:1–4.

Fullerton JT, Johnson P, Lobe E, et al. A rapid assessment tool for affirming good practice in midwifery education programming. Midwifery. 2016;34(2016):36–41.

G. Farooq Mansoor, Pashtoon Hashemy, Fatima Gohar, Molly E. Wood, Sadia F. Ayoubi, Catherine S. Todd. Midwifery retention and coverage and impact on service utilization in Afghanistan. Midwifery 29 (2013)1088–1094.

International Confederation of Midwives.; Core document. International definition of Midwife. URL: https://www.internationalmidwives.org/assets/files/definitions-files/2018/06/eng-definition_of_the_midwife-2017.pdf (last accessed 16 March 2020)

World Health Organization. 2014. Midwifery educator core competencies. ISBN 978 92 4 150645 8.

UNFPA. 2014. State of Afghanistan’s Midwifery 2014. URL https://afghanistan.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/MidwiferyReport_English.pdf (last accessed 22 March 2020).

World Health Organization. Strengthening quality midwifery education for universal health coverage 2030: framework for action. Geneva: WHO; 2019.

Yigzaw T, Ayalew F, Kim YM, et al. How well does pre-service education prepare midwives for practice: competence assessment of midwifery students at the point of graduation in Ethiopia. BMC Medical Education. 2015;15:130.

World Health Organization. 2015. Midwifery educator core competencies: building capacities of midwifery educators. ISBN 978 92 4 150822 3. .

World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. 2015. A guide to nursing and midwifery education standards. ISBN 978–92–9022-081-7. ISBN (online) 978–92–9022-082-4.

Bharj, K.K, Luyben A, Avery M.D. et al. An agenda for midwifery education: advancing the state of the world’s midwifery. Midwifery. 2016;33:3–6.

Turkmani S, Gohar F, Shah F, Hamnawazada S, Zyaee P. Strengthening Midwifery education, regulation and association; a case study from Afghanistan. Journal of Asian Midwives. 2015;2(1):6–13.

Sofia Castro Lopes, Andrea Nove1, Petra ten Hoope-Bender et al. A descriptive analysis of midwifery education, regulation and association in 73 countries: the baseline for a post-2015 pathway. Hum Resour Health 2016; 14:37.

Petra ten Hoope-Bender, de Bernis L., Campbell et al. Improvement of maternal and newborn health through midwifery. Lancet. 2014; 384: 1226–1235.

Renfrew MJ, Mcfadden A, Bastos MH, et al. Midwifery and quality care: findings from a new evidence- informed framework for maternal and newborn care. Lancet. 2014;384:1129–45.

Homer C.S, Friberg I.K, Dias M.A. et al. The projected effect of scaling up midwifery. Lancet 2014: 384: 1146–1157.

United Nations Population Fund. 2021. The state of the World's Midwifery 2021. URL: https://www.unfpa.org/publications/sowmy-2021

Ministry of Public Health. 2011. National Policy & Strategy for nursing and Midwifery services (draft X). URL: https://extranet.who.int/countryplanningcycles/sites/default/files/planning_cycle_repository/afghanistan/afghanistan_nuring_and_midwifery_services_policy_2011-2015_draft.pdf (Accessed March 22 2020).

Smith J.M, Currie S, Azfar P, Rahmanzai A.J. Establishment of an accreditation system for midwifery education in Afghanistan: maintaining quality during national expansion. Public Health 2008; 122, 558–567.

Fullerton J.T, Johnson P.G, Thompson J.B, Vivio D. Quality considerations in midwifery pre-service education: exemplars from Africa. Midwifery 2011; 27: 308–315.

Kibwana S, Haws R, Kols A, et al. Trainers’ perception of the learning environment and student competency: a qualitative investigation of midwifery and anesthesia training programs in Ethiopia. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;55:5–10.

Gavine A, MacGillivray S, McConville F, Gandhi M, Renfrew MJ. Pre-service and in-service education and training for maternal and newborn care providers in low- and middle-income countries: an evidence review and gap analysis. Midwifery. 2019;78:104–13.

Ministry of Public Health. 2011. Afghanistan National health workforce plan for 2012–2106. 2011 (draft). URL: https://www.who.int/workforcealliance/countries/Afghanistan_HRHplan_2012_draft.pdf (Accessed March 22 2020).

Kruk ME, Gage AD, Arsenault C, et al. High-quality health systems in the sustainable development goals era: time for a revolution. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;20(6):e1196–252.

World Health Organization. 2016. Midwives’ voices, midwives’ realities: findings from a global consultation on providing quality midwifery care. WHO, Geneva. ISBN 978 92 4 151611 2.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge that this study was made possible by the facilitation of the Ministry of Public Health of Afghanistan, cooperation of the Afghan Midwives Association and collaboration of the public and private midwifery schools and their managers, students and faculty members. We also would like to thank the study team and data collectors, including Ahmad Eklil Hossain, Enayatullah Mayar, Said Raouf Saidzada, Fahima Naziri, Farzana Darkhani, Kobra Ibrahimi, Lailoma Barakzai, Marzia Naimi, Matiullah Noorzad, Nooria Naseri, Roya Hamdard, Shafiqa Inzari, Shakila Abdali, Shakila Nikzad, Wahida Zahiri, Zahra Mirzaei, Zahra Nikzad, Zahra Zamani, Abdul Qader Rahimi, Ali Reza, Aminullah Mahboobi, Asma, Bezhan Nasiri, Fatima Noori, Freshta Ahmadi, Javid Matin, Khesraw Parwiz, Mahmood Azimi, Moqadisa Nikzad, Moslema Mohammadi, Noor Hassan Shirzad, Roya Rasa Azimi, Sayed Abdul Malik Hashemi, Sayed Ahmad Gawhari, Sayed Mohammad Hamed Hamedi, Sediqa Karimi, Shafiq Ahmad Yousofi, Shah Mohammad Qazizada, Zabihullah Rahmani, Zahra Kochizada, and Zainab Hashemi. Last but not least, we acknowledge and appreciate Abbey Becker, Beckah Walsh and Naomi Bouchard-Gordon for their support in copyediting and formatting of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PM: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, analysis, writing of the manuscript; design and implementation of the research. MJ: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, analysis, writing of the manuscript. SC: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, analysis, writing of the manuscript; design and implementation of the research. FA: Writing, review & editing, implementation of the research. NA: Conceptualization, writing, review & editing, implementation of the research. HT: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, analysis, writing of the manuscript; design and implementation of the research. YMK: Writing, review & editing. JR: Writing, review & editing. JS: Writing, review & editing. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Afghan Public Health Institute Review Board (IRB #43876) approved the assessment. The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board also considered the assessment as not human subjects research. Data collectors obtained verbal informed consent from each participant, and did not collect any personal information about school managers, teachers, preceptors and students.

Hereby we confirm that all methods were performed in accordance with all relevant items of the STROBE Statement—Checklist of items that should be included in reports of cross-sectional studies.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The assessment was funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Afghanistan FP/MNCH Project (AID-306-A-15-00002) The contents of this manuscript are the responsibility of the authors; the funder had no roles in the design of the study, data collection, analysis, interpretation and writing the manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Manalai, P., Currie, S., Jafari, M. et al. Quality of pre-service midwifery education in public and private midwifery schools in Afghanistan: a cross sectional survey. BMC Med Educ 22, 39 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-03056-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-03056-1