Abstract

Background

Although general medicine (GM) faculty in Japanese medical schools have an important role in educating medical students, the importance of residents’ rotation training in GM in postgraduate education has not been sufficiently recognized in Japan. To evaluate the relationship between the rotation of resident physicians in the GM department and their In-Training Examination score.

Methods

This study is a nationwide multi-center cross-sectional study in Japan. Participants of this study are Japanese junior resident physicians [postgraduate year (PGY)-1 and PGY-2] who took the General Medicine In-Training Examination (GM-ITE) in fiscal years 2016 to 2018 at least once (n = 11,244). The numbers of participating hospitals in the GM-ITE were 381, 459, and 503 in 2016, 2017, and 2018.The GM-ITE score consisted of four categories (medical interview/professionalism, symptomatology/clinical reasoning, physical examination/procedure, and disease knowledge). We evaluated relationship between educational environment (including hospital information) and the GM-ITE score.

Results

A total of 4464 (39.7%) residents experienced GM department rotation training. Residents who rotated had higher total scores than residents who did not rotate (38.1 ± 12.1, 36.8 ± 11.7, and 36.5 ± 11.5 for residents who experienced GM rotation training, those who did not experience this training in hospitals with a GM department, and those who did not experience GM rotation training in hospitals without a GM department, p = 0.0038). The association between GM rotation and competency remained after multivariable adjustment in the multilevel model: the score difference between GM rotation training residents and non-GM rotation residents in hospitals without a GM department was estimated as 1.18 (standard error, 0.30, p = 0.0001), which was approximately half of the standard deviation of random effects due to hospital variation (estimated as 2.00).

Conclusions

GM rotation training improved the GM-ITE score of residents and should be considered mandatory for junior residents in Japan.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

General medicine (GM) has an important role in health care systems of Western countries. In 1956, the University of Edinburgh opened a Department of GM for the first time in the world. GM physicians have been recognized as specialists of primary care in many European countries with universal health care coverage. The United States health care system has developed a comprehensive GM system, including family medicine for primary care, general internal medicine (GIM) for hospital outpatient care, and hospital medicine for inpatient hospital care [1, 2].

In Japan, a GM department was introduced at Tenri Yorozu Soudan Sho Hospital, a community teaching hospital, in 1976 for the first time [3]. Thereafter, GM departments have been increasing steadily among other community teaching and university hospitals. Physicians in GM departments in Japanese hospitals provide outpatient and/or inpatient care for patients with complex problems and multiple co-morbidities, and who cannot be cared for by sub-specialist physicians.

Although GM faculty members in many Japanese medical schools have important roles as clinician educators for medical students, the importance of GM in a postgraduate residency education has not been sufficiently recognized in Japan [4]. Thus, a 2-year training program for postgraduate junior resident physicians has become mandatory in Japan since 2004, but many junior residents are not required to have rotation training in GM department and are required to have rotations in internal medicine (mostly subspecialty internal medicine divisions), emergency medicine, community medicine, surgery, psychiatry, pediatrics, and obstetrics/gynecology.

Learning objectives in the training program for postgraduate junior resident physicians include many areas related to GM care settings. We believe that GM rotation training has a great effect on the educational achievements of resident physicians. We previously reported a positive association between the presence of a GM department at each teaching hospital and mean scores on the General Medicine In-Training Examination (GM-ITE) among junior residents [5]. However that study was based on an ecological design and did not evaluate the association between GM rotation training and the test scores for individual residents. In the current study, we evaluated the relationship between GM rotation training for residents and their GM-ITE score. We also evaluated the relationship between the GM-ITE scores and factors associated with the educational environment, including time spent on Emergency Department (ED) duties per month, average number of inpatients covered per day, availability and use of online medical resources, and the amount of study time per day.

We have divided the students participating in a GM rotation into three groups, including (1) those with no previous GM experience (i.e., GM rotation) who were trained in hospitals without a GM department (2) those with no previous GM experience who were trained in hospitals that included a GM department, and (3) those with previous GM experience. Teaching hospitals in Japan, regardless of whether or not they have a GM department, all have individual subspecialty divisions of Internal Medicine, including Cardiology, Hematology, Nephrology, and Respiratory Medicine.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a nationwide, multi-center, cross-sectional study in Japan. We evaluated the association between the educational environment and the GM-ITE score from the fiscal years 2016 to 2018 among resident physicians in Japanese teaching hospitals. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Mito Kyodo General Hospital, Mito City, Ibaraki, Japan.

GM-ITE

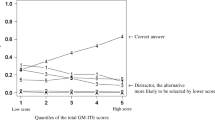

The Japan Organization of Advancing Medical Education Program (JAMEP), a non-profit organization, has been implementing the GM-ITE since 2011 as an objective evaluation of the basic clinical competency of junior resident physicians (postgraduate years PGY-1 and PGY-2) [5,6,7,8,9]. The GM-ITE is a multiple-choice knowledge test. In 2016, it consisted of 100 questions. Following revisions in 2017 and 2018, the test has 60 questions.

In line with the early residency objectives of the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, the GM-ITE covers four areas of basic clinical knowledge: medical interview and professionalism, symptomatology and clinical reasoning, physical examination and procedure, and disease knowledge. The test items relate to the fields of internal medicine, surgery, emergency medicine, pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology, and psychiatry. Overall, the GM-ITE comprehensively covers all the relevant disciplines with a focus on primary care.

The test content and construct validity have been proven. Upon completing the test, test-takers receive feedback based on the relative scoring of the test participants and a detailed explanation about each question. A sample English question from the GM-ITE is shown in the Additional file 1: Appendix.

Data collection

We collected information about the educational environment from a self-reporting questionnaire sheet, which included age, future desired specialty after residency, GM rotation, period of internal medicine rotation, ED duties per month, night duties per month, average number of inpatients in charge, use of medical online resources [including UpToDate (www.uptodate.com) [10]], medical journals, medical manuals, medical information websites, study time per day, number of participating case conferences per week, number of participating outside case conferences or lectures, and contribution by the GM department. Hospital information was obtained from the Residency Electronic Information System website [11] and the Foundation for the Promotion of Medical Training website [12]. Regarding the categories of urban cities and local cities in the hospital characteristics, 20 cities designated by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications and in the 23 wards in Tokyo were defined as urban cities and the rest as provincial cities.

Statistical analyses

Resident physicians were classified into three groups according to their hospitals with or without a GM department and the experience of GM rotation from a self-reporting questionnaire sheet (hospitals without a GM department did not offer GM rotation). We compared the GM-ITE total scores between the GM department/rotation groups by using linear multilevel regression models adjusted for hospital-level information (hospital location and hospital type) and resident-level information (sex, deviation value of graduating school in 2018, ED duties per month, average number of inpatients in charge, UpToDate use, study time per day, and year of GM-ITE) as well as hospitals as random normal intercepts. Residents with missing data for any variable were excluded from the multivariate analysis. All analyses were performed by using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). We interpreted p-values as indicative of compatibility between the data and the “no-difference between that variable’s levels” hypothesis under the assumed statistical model.

Results

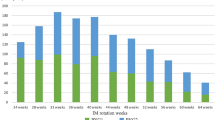

Throughout Japan, 381, 459, and 503 hospitals participated in the GM-ITE in 2016, 2017, and 2018, and the numbers of GM-ITE participants were 4568, 5593, and 6133, respectively, for each year. If consent for utilizing the GM-ITE score could not be obtained, those data were excluded from the analyses. If a resident physician took the examination twice (in PGY-1 and PGY-2), we excluded the data from PGY-1. Finally, the data of 11,244 resident physicians were used for analyses.

Summarized hospital information, resident information, and GM-ITE scores are shown in Table 1. A total of 11,244 residents (67.7% men) were retrospectively analyzed. Among the hospitals, 26.8% were urban and 88.8% were community hospitals. The average total GM-ITE scores were 37.3 ± 11.9 and 5.9 ± 5.4 for medical interview and professionalism, 10.6 ± 2.5 for symptomatology and clinical reasoning, 10.3 ± 2.5 for physical examination and procedure, and 10.5 ± 4.2 for disease knowledge.

A total of 4464 (39.7%) residents experienced rotation training in the GM department. Residents who rotated in the GM department had higher total scores than residents who did not rotate. The results were 38.1 ± 12.1, 36.8 ± 11.7, and 36.5 ± 11.5 for residents who experienced GM rotation training, those who did not experience GM rotation in hospitals with a GM department, and those who did not experience GM rotation in hospitals without a GM department (p = 0.0038).

The association between GM department/rotation remained after multivariable adjustment in the multilevel model (Table 2): the score difference between residents who experienced GM rotation training and those who did not in hospitals without a GM department was estimated as 1.18, with a standard error of 0.30 (p = 0.0001), which was about half of the standard deviation of random effects due to hospital variation (estimated as 2.00). The analysis also showed that community hospital, male sex, deviation value, ED duties per month (three to five per month vs. zero per month: estimated coefficient, 1.22; standard error, 0.40; p = 0.0022), average number of inpatients in charge (> 15 vs. zero to four: estimated coefficient, 1.18; standard error, 0.40; p = 0.0036), UpToDate use (estimated coefficient, 1.48; standard error, 0.16; p < 0.0001), study time (61–90 min vs. none: estimated coefficient, 1.65; standard error, 0.39; p < 0.0001), test year, and GM rotation training were associated with the total GM-ITE score.

Table 3 includes the results of subgroup multilevel regression analyses that evaluate the relationship between the GM rotation and the GM-ITE score (Table 3). Overall, we found no obvious difference in relationships between the GM rotation and the GM-ITE score with respect to each subgroup except for hospital type (community hospitals vs. university hospitals).

Discussion

We found a positive relationship between the experience of GM rotation training and the total GM-ITE score. The contribution for improving the GM-ITE score ranged from highest to lowest as follows: experienced GM rotation training > did not experience GM rotation training in hospitals with a GM department > did not experience GM rotation training in hospitals without a GM department. These results suggest that educational achievement in junior residents could be improved by their GM rotation training. We also found the several significant factors associated with the educational environment that had an impact on the GM-ITE score, including ED duties (shifts per month), average number of inpatients covered per day, availability and use of online medical resources, and amount of study time per day. Although amount of study time and use of effective learning materials are important factors with direct impact on test preparedness, we found no specific change in relationships between the GM rotation and the GM-ITE score across subgroups of these factors.

We have previously reported that residents in teaching hospitals with higher mean GM-ITE scores were associated with the presence of a GIM or GM department [5]. However, that study was an investigation with a small sample size of 206 residents at 21 hospitals. Furthermore, because there was no questionnaire survey on the educational environment, the association between GM rotation and GM-ITE score was not verified. In this study, we used a larger sample size and more directly evaluated the effect of GM rotation training on educational achievements/competency by specifically investigating the relationship between GM rotation training and the GM-ITE score for residents.

We believe bedside teaching by general physicians provides greater effectiveness of clinical education. The GM department covers all areas of medicine with a broad view to patient care and does not focus on a single organ system, so training programs involving GM rotation positively affect the GM-ITE score. Moreover, general physicians are good at teaching essential elements for basic clinical competency, such as clinical ethics, communication, physical examination, clinical reasoning, and professionalism [13,14,15].

Compared with Western countries, Japan has a shorter history of developing GM departments in hospitals, so these have not been recognized as a required department for educational rotation of junior residents [16,17,18]. However, since there is a broad overlap of core competencies between GM physicians and junior residents, rotation training in this department is highly desirable. From 2018, the designation of “general physician” has been newly acknowledged as a specialist in a basic area of the Japanese medical specialty system [19, 20]. It is hoped that this change will serve as an opportunity to introduce GM departments in all teaching hospitals throughout Japan.

The hospitalist plays a crucial role in improving the quality of resident physician education [21]. As in the United States, Japanese hospitals should have a GM department at the center of the medical ward, and it is necessary to build a system in which general physicians take care of the patient along with the resident in the medical ward and have the option to immediately consult with sub-specialist physicians if necessary. Further, sub-specialist physicians should be able to consult general physicians in order to facilitate a smooth diagnosis [2, 22].

We found that resident physicians with ED duty three to five times per month were associated with the highest GM-ITE scores relative to those with no ED duty per month. Residents with three to five instances of ED duty per month had higher GM-ITE scores than residents with more than six instances per month. The results revealed a trend similar to that of a previous study we reported in 2015 [6]. An appropriate workload in ED duty may develop better competencies and lead to better educational achievements among resident physicians. On the other hand, an excessive workload may cause “burn out” or more medical errors [23,24,25]. Burnout is a psychological syndrome that is experienced frequently by medical residents. It consists of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and reduced feelings of personal accomplishment [26]. Trigger factors for burnout among emergency physicians and emergency medicine residents include non-patient-related problems (such as large administrative burdens) in addition to personal and interpersonal issues [27]. Shanafelt et al. reported differences in burnout by specialty; the highest rates of burnout are reported among physicians on the front lines of medical care (i.e., family medicine, general internal medicine, and emergency medicine). This group also reported that, compared with a probability-based cohort sample of 3442 working U. S. adults, physicians were more likely to have symptoms of burnout (37.9% vs 27.8%) and to be dissatisfied with their current level of work-life balance (40.2% vs 23.2%) [28]. Therefore, we should require continual awareness of the optimized workload balance in ED duties to provide a safer educational environment for resident physicians.

We showed that resident physicians in charge of > 15 inpatients had higher GM-ITE scores than residents in charge of 0 to 4 inpatients. We also demonstrated a relationship between appropriate study time and higher GM-ITE score. The explanation for this observation lies in the following witty remark by William Osler: “To study the phenomena of disease without books is to sail an uncharted sea, while to study books without patients is not to go to sea at all” [29, 30].

UpToDate use was associated with higher GM-ITE scores. The results coincided with those of our previous report [6]. Physicians need to effectively collect clinical evidence for a short period in a clinical situation. Self-directed reading of an electronic knowledge resource have been found previously to have statistically and educationally significant independent associations with medical knowledge acquisition [31]. In addition, efficient collection of clinical evidence by using UpToDate could improve not only medical knowledge but also prognoses of patients [32, 33]. We expect resident physicians to appropriately use evidence-based electronic resources for bedside and clinical decision making.

Brint and Cantwell reported that more time spent focused on learning results in improved performance on examinations [34]; reports from other groups revealed that use of online resources resulted in improved student performance [35, 36]. Our findings are consistent with the results of these earlier studies.

We found that the group of “no experience of GM rotation in hospitals with GM department” tended to obtain the higher GM-ITE score than the group of “no experience of GM rotation in hospitals without GM department”. Even if junior resident physicians had no previous GM experience, GM departments tend to have an overall profound educational impact on resident physicians. GM departments typically include faculty development programs that provide outreach to all departments. GM physicians are also among the most likely to provide resident physicians lectures and conferences that cover topics that are critical for clinical training including ethics, communication skills, professionalism, and evidence-based medicine.

As shown in Table 3, there was no apparent difference in relationship between having the experience of a GM rotation and the GM-ITE score with respect to location (i.e., urban area vs. rural area). On the other hand, there were significant differences in the relationship between hospital type subgroups (community hospitals vs. university hospitals), with the university hospitals having a greater GM rotation and the GM-ITE score associations than community hospitals. The estimated coefficient for “having experienced a GM rotation” was 1.1 in community hospitals and 3.6 in university hospitals. We hypothesize that this result may reflect differences in the environment related to primary care education and thus a higher educational impact of the GM rotation.

The present study revealed a positive association between having participated in a GM rotation and GM-ITE score. In addition to the positive impact of a GM rotation, we think that the potential negative impact of limited training in specialized medical departments should not be overlooked. In modern clinical practice, physicians are asked to care for patients with complex medical problems and multiple co-morbidities. As such, physicians who are focused purely on one organ or organ system may have a more narrow vision, and thus may provide a limited educational view for junior resident physicians. Furthermore, learning objectives for postgraduate junior resident physicians include aspects such as ethics, communication skills, professionalism, and evidence-based medical practice, among other more general topics. It is unlikely that a medical sub-specialist will have the knowledge or interest in taking charge of so wide a range of educational requirements. Given this situation, we feel strongly that further enrichment of the education system with a strong focus on GM departments will ensure that the next generation of physicians is fully equipped to deal with a wide range of problems.

However, there are other points that require some future consideration. Sub-specialists may need to put in more effort towards identifying cross-disciplinary solutions for both social and medical problems, including the doctor–patient relationship, problems associated with mental and psychological well-being as well as social welfare, and various approaches that feature input from those knowledgeable in the behavioral sciences. Furthermore, sub-specialists may need to contribute toward patient-centered health education regarding smoking, drinking alcohol, and drug abuse. The sub-specialists will need to foster and nurture sensitivity toward these problems; we recognize that this will be a substantial paradigm-shift from the current disease-oriented approach [3].

We were unable to identify any specific factors underlying the gender differences in the GM-ITE scores. This result did not necessarily mean that female resident physicians possess less knowledge or fewer skills than do their male resident physicians. Additional analysis with representative data will be needed to address this issue.

Our study had several limitations. First, we did not include all initial training participants belonging to teaching hospitals in Japan. The number of PGY-1 plus PGY-2 resident physicians was approximately 18,000, but about one-third of resident physicians participate in the GM-ITE. Therefore, our findings might not be generalizable to all residents throughout Japan.

Second, we did not evaluate the residents’ baseline GM-ITE score. For a more precise measurement of the impact of general medicine rotation training on the GM-ITE score, the baseline GM-ITE score should be adjusted.

Third, we did not take the participants’ medical school experiences into consideration. The learning experiences of GM training depend on one’s medical school education. This may have affected the study results.

The fourth limitation is the season of the GM rotation, that is, the GM-ITE scores are affected if the season of the GM rotation is close to the time of testing. We were not able to adjust this factor.

Finally, the study variables did not include some that might have affected the results. For example, the number of supervising physicians belonging to a GM department and the years of clinical experience of the supervising physicians and contents of their educational programs could affect the learned competencies and GM-ITE scores of the residents. Future studies are needed to confirm the direct relationship between GM rotation training and GM-ITE scores after adjusting for the variables mentioned above.

Conclusion

GM rotation training led to improvement in the GM-ITE score of residents. Therefore, mandatory GM rotation training should be considered for junior residents in Japan.

Availability of data and materials

The data sets will not be publicly available because informed consent of participants in each hospital do not allow for such publication. The corresponding author will respond to requests on data analyses.

Abbreviations

- ED:

-

Emergency department

- GIM:

-

General internal medicine

- GM:

-

General medicine

- GM-ITE:

-

General Medicine In-Training Examination

- JAMEP:

-

Japan Organization of Advancing Medical Education Program

- PGY:

-

Postgraduate year

References

Policy statement for general internal medicine fellowships. Society of General Internal Medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 1994;9:513–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02599222 PMID: 7996295.

Ranji SR, Rosenman DJ, Amin AN, Kripalani S. Hospital medicine fellowships: works in progress. Am J Med. 2006;119:72.e1–7. 16431196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.07.061.

Fukui T. General internal medicine. Nihon Naika Gakkai Zasshi. 2002;91:3106–10. https://doi.org/10.2169/naika.91.3106 PMID 12652750.

Heist BS, Matsubara Torok H, Michael ED. Working to change systems: repatriated U.S. trained Japanese physicians and the reform of generalist fields in Japan. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31(4):412–23. 30849234. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2019.1574580.

Shimizu T, Tsugawa Y, Tanoue Y, Konishi R, Nishizaki Y, Kishimoto M, et al. The hospital educational environment and performance of residents in the General Medicine In-Training Examination: a multicenter study in Japan. Int J Gen Med. 2013;6:637–40. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S45336 PMID 23930077.

Kinoshita K, Tsugawa Y, Shimizu T, Tanoue Y, Konishi R, Nishizaki Y, et al. Impact of inpatient caseload, emergency department duties, and online learning resource on General Medicine In-Training Examination scores in Japan. Int J Gen Med. 2015;8:355–60. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S81920 PMID 26586961.

Mizuno A, Tsugawa Y, Shimizu T, Nishizaki Y, Okubo T, Tanoue Y, et al. The impact of the hospital volume on the performance of residents on the general medicine in-training examination: A multicenter study in Japan. Intern Med. 2016;55:1553–8. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.55.6293 PMID 27301504.

Nishizaki Y, Shinozaki T, Kinoshita K, Shimizu T, Tokuda Y. Awareness of diagnostic error among Japanese residents: a nationwide study. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:445–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4248-y PMID 29256086.

Nishizaki Y, Mizuno A, Shinozaki T, Okubo T, Tsugawa Y, Shimizu T, et al. Educational environment and the improvement in the General Medicine In-training Examination score. J Gen Fam Med. 2017;18:312–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgf2.57 PMID 29264056.

UpToDate [internet]. http://www.uptodate.com. Accessed 15 Sept. 2019.

REIS (Residency Electronic Information System) [internet]. https://www.iradis.mhlw.go.jp/reis/common/ad0.xhtml. Accessed 15 Sept. 2019.

PMET (Foundation for the Promotion of Medical Training) [internet]. http://guide.pmet.jp/web2018/index.html. Accessed 15 Sept. 2019.

William McCarthy M, Fins JJ. Teaching clinical ethics at the bedside: William Osler and the essential role of the hospitalist. AMA J Ethics. 2017;19:528–32. https://doi.org/10.1001/journalofethics.2017.19.6.peer2-1706 PMID 28644781.

Farnan JM, O'Leary KJ, Didwania A, Icayan L, Saathoff M, Bellam S, Anderson A, Reddy S, Humphrey HJ, Wayne DB, Arora VM. Promoting professionalism via a video-based educational workshop for academic hospitalists and housestaff. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:386–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2056 PMID 23780912.

Janjigian MP, Charap M, Kalet A. Development of a hospitalist-led-and-directed physical examination curriculum. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:640–3. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.1954 PMID 22791266.

Otaki J. Considering primary care in Japan. Acad Med. 1998;73:662–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199806000-00013 PMID 9653405.

Ishizuka T. Specialists in internal medicine and subspecialties. Nihon Naika Gakkai Zasshi. 2008;97:1130. https://doi.org/10.2169/naika.97.1130.

Ishizuka T. Fellow of JSIM and Pramary care. Face reality, and future prospects. Nihon Naika Gakkai Zasshi. 2009;98:3170–4. https://doi.org/10.2169/naika.98.3170.

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare [internet]. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/kenkou_iryou/iryou/rinsyo/index_00011.html. Accessed 15 Sept. 2019.

Japanese Medical Specialty Board [internet]. https://www.japan-senmon-i.jp/comprehensive.html. Accessed 15 Sept. 2019.

Hauer KE, Wachter RM, McCulloch CE, Woo GA, Auerbach AD. Effects of hospitalist attending physicians on trainee satisfaction with teaching and with internal medicine rotations. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1866–71. 15451761. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.164.17.1866.

Ishiyama T. Critical roles of “J-hospitalist”. J Gen Fam Med. 2015;16:153–7. https://doi.org/10.14442/jgfm.16.3_153.

Block L, Wu AW, Feldman L, Yeh HC, Desai SV. Residency schedule, burnout and patient care among first-year residents. Postgrad Med J. 2013;89:495–500. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131743 PMID 23852828.

Blanchard P, Truchot D, Albiges-Sauvin L, Dewas S, Pointreau Y, Rodrigues M, et al. Prevalence and causes of burnout amongst oncology residents: a comprehensive nationwide cross-sectional study. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:2708–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2010.05.014 PMID 20627537.

Arnedt JT, Owens J, Crouch M, Stahl J, Carskadon MA. Neurobehavioral performance of residents after heavy night call vs after alcohol ingestion. JAMA. 2005;294:1025–33. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.294.9.1025 PMID 16145022.

Rodrigues H, Cobucci R, Oliveira A, Cabral JV, Medeiros L, Gurgel K, et al. Burnout syndrome among medical residents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0206840. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0206840 PMID: 30418984.

Verougstraete D, Hachimi IS. The impact of burn-out on emergency physicians and emergency medicine residents: a systematic review. Acta Clin Belg. 2020;75:57–79. 31835964. https://doi.org/10.1080/17843286.2019.1699690.

Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, Dyrbye LN, Sotile W, Satele D, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1377–85 PMID: 22911330.

Osler W. Address on the dedication of the new building. Boston Med Surg J. 1901;144:60–1. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM190101171440304.

Shimizu T, Nemoto T, Tokuda Y. Effectiveness of a clinical knowledge support system for reducing diagnostic errors in outpatient care in Japan: A retrospective study. Int J Med Inform. 2018;109:1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2017.09.010 PMID 29195700.

McDonald FS, Zeger SL, Kolars JC. Factors associated with medical knowledge acquisition during internal medicine residency. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:962–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0206-4 PMID 17468889.

Isaac T, Zheng J, Jha A. Use of UpToDate and outcomes in US hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:85–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.944 PMID 22095750.

Phua J, See KC, Khalizah HJ, Low SP, Lim TK. Utility of the electronic information resource UpToDate for clinical decision-making at bedside rounds. Singap Med J. 2012;53:116–20 PMID 22337186.

Brint S, Cantwell AM. Undergraduate time use and academic outcomes: results from the University of California Undergraduate experience survey 2006. Teach Coll Rec. 2010;112:2441–70.

Donkin R, Askew E, Stevenson H. Video feedback and e-learning enhances laboratory skills and engagement in medical laboratory science students. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19:310. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1745-1 PMID: 31412864.

Johnson MT. Impact of online learning modules on medical student microbiology examination scores. J Microbiol Biol Educ. 2008;9:25–9 PMID: 23653820.

Acknowledgments

We thank the JAMEP secretariat for their excellent support for our work.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YN and YT have designed this study in whole and drafted this manuscript. TS 1, TO, YY, and RK have contributed to collect data. TS 2 has contributed to statistical analyses in this study. All authors have contributed to provide advice on interpretation of the results. YT has revised this manuscript critically for important intellectual content and approved finally the manuscript submitted. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Mito Kyodo General Hospital, Mito City, Ibaraki, Japan. We obtained written consent from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

YN, TS 1, TO, YY, RK, and YT participated on the JAMEP GM-ITE project committee and received a reward.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Nishizaki, Y., Shimizu, T., Shinozaki, T. et al. Impact of general medicine rotation training on the in-training examination scores of 11, 244 Japanese resident physicians: a Nationwide multi-center cross-sectional study. BMC Med Educ 20, 426 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02334-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02334-8