Abstract

Background

The plant Holarrhena floribunda (H. floribunda; G. Don) is indigenous to sub-Saharan Africa and is traditionally used to treat several ailments. The present study was carried out to isolate and characterize bioactive compounds with anti-proliferative activity present in H. floribunda extracts.

Methods

Compounds were isolated from H. floribunda using the bioassay-guided fractionation technique of repeated column chromatography and the step-wise application of the MTT reduction assay to assess antiproliferative bioactivity. The structures of the compounds were identified mainly using NMR. The effects of the isolated compounds on the viability, cell cycle and proliferation of human cancer cell lines (MCF-7, HeLa and HT-29) as well as the non-cancerous human fibroblast cell line (KMST-6) were investigated.

Results

Bioassay-guided fractionation yielded two steroidal alkaloids: holamine (1) and funtumine (2). The MTT reduction assay shows that both compounds exhibited selective dose-dependent cytotoxicity against the cancer cell lines studied. The isolated compounds induced cell cycle arrest at the G0/G1 and G2/M phases in the cancer cell lines with significant reduction in DNA synthesis. The results obtained show that the cancer cells (MCF-7, HeLa and HT-29) used in this study were more sensitive to the isolated compounds compared to the noncancerous fibroblast cells (KMST-6).

Conclusion

The ability of the isolated compounds to cause cell cycle arrest and reduce DNA synthesis raises hopes for their possible development and use as potent anticancer drugs. However, more mechanistic studies need to be done for complete validation of the efficacy of the two compounds.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Plants are a reservoir of compounds with chemical diversity that provides leads for the discovery of new drugs against human diseases [1]. Folklore medicine as practiced worldwide demonstrates that plants are an important and reliable source of bioactive antitumour, antioxidant and antimicrobial compounds [2]. Assessing plants used in traditional medicine for various biological capabilities necessitates the isolation and characterization of bioactive components as leads for drug development. The African continent lays claim to about 45,000 plant species, of which about 5000 are used for medicinal purposes [3]. Despite the huge potential presented by this number of species, only 83 out of the 1100 potential drugs sourced from the African continent have been selected as candidates for preclinical drug development and screening platforms [3].

Out of the colossal number of 250,000–500,000 world flora species, only 1–10% of plants have been scientifically evaluated [4]. There is a huge gap between the natural flora endowment and human ability to harness the biodervisity for developing drugs, especially against cancer, with minimal or no adverse reactions. The medicinal constituents derived from plants are not only important as therapeutic agents, but could also serve as templates for the synthesis of active drugs with desired therapeutic profiles [5]. This has opened new vistas for delineating the structural importance of bioactive components of plants. A typical example is camptothecin, which has been developed into different analogues (topotecan, irinotecan, belatecan and 9-aminocamptothecin) [6].

Holarrhena floribunda (G. Don) is a plant with an approximate height of 17 m and girth of 1 m. The plant belongs to the family of Apocynaceae and is commonly found in secondary regeneration in deciduous forests, savanna woodlands in Senegal, Nigeria and in the Congo basin [7]. Apocynaceae, the dogane family of flowering plants includes more than 250 genera and 2000 species of trees, shrubs, woody vines and herbs distributed primarily in tropical and subtropical areas of the world [8]. All the members of the family are known to produce abundant milky latex; simple, opposite and whorled leaves; slightly fragrant, colourful and large flowers with five contorted lobes; and with paired fruits [8]. The most common plant-derived compounds with potential medicinal properties are alkaloids, cardiotonic glycosides, saponin, and iridoids [8]. Some bioactive natural products isolated from Apocynaceae include vinblastine, quabain, reserpine and ibogaine. The alkaloids of the family have been historically useful to treat cancer with many other compounds awaiting discovery [8]. Some members of the Apocynaceae family reported to have anticancer properties include Nerium oleander [9], Alstonia macrophylla [10], Cerbera manghas [11] and Calotropis gigantean [12]. However, based on an ethnomedical survey conducted by Abreu et al. (1999) in accordance with disposition of local healers in the Contuboel region of Guinea-Bissau, H. floribunda was screened along with seventeen other plant extracts for antimicrobial, antitumour and antileishmania activity [13]. The extract of H. floribunda was found to have significant antitumor effects against KB (squamous carcinoma), SK-Mel 28 (melanoma), A549 (lung carcinoma) and MDA-MB 231 (human breast carcinoma) cell lines [13]. We have also previously reported on the antiproliferative and apoptotic effects of the methanolic leaf extract of H. floribunda against HeLa (cervical carcinoma), MCF-7 (breast carcinoma) and HT-29 (colorectal carcinoma) cell lines [14].

The objective of this research was to isolate, purify and characterize the bioactive components of the methanolic leaf extract (MLE) of H. floribunda, using bioactivity-guided fractionation and to investigate the cytotoxic effects of the isolated compounds in cancerous (HeLa, MCF-7 and HT-29) and non-cancerous (KMST-6) human cell lines by evaluating the effects of the compounds on cell cycle and DNA synthesis.

Methods

Plant material

Holarrhena floribunda (G. Don) leaves were collected in Igbajo, Osun State, Nigeria, during the rainy season. It was identified, authenticated and deposited at the Federal Research Institute of Nigeria (FRIN) herbarium with voucher number FHI 10976.

Chemicals and reagents

Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), tetrazolium salt 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol- 2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), penicillin-streptomycin, potassium iodide (PI), trypsin, solvents (chloroform, ethylacetate, methanol), paraformaldehyde and RNase were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were obtained from Gibco (USA) and alumina oxide from Fluka (AG, Buch, Switzerland). The ELISA-BrdU kit was purchased from Roche Diagnostic GmbH (Mannheim, Germany).

Maintenance of cell culture

The cancer cell lines, HT-29 (human colon adenocarcinoma), Hela (human cervical cancer), MCF-7 (human breast adenocarcinoma) and the non-cancerous human fibroblast cell line (KMST-6) used in this study were generously provided by Prof Denver Hendricks (Department of Clinical and Laboratory Medicine, University of Cape Town, South Africa). All cell culture operations were carried out in a model NU-5510E NuAire DHD autoflow automatic CO2 air-jacketed incubator and an AireGard NU-201-430E horizontal laminar airflow tabletop workstation that provides a HEPA filtered clean work area (NuAire). The cell lines were maintained in complete DMEM growth medium supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin). The cells were maintained as monolayer cultures at 37 °C in a humidified incubator (relative humidity 80%) in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air.

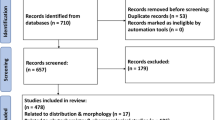

Fractionation of methanolic leaf extract (MLE) of Holarrhena floribunda

Pulverized plant material (1.75 kg) was extracted with methanol (5 L) as previously reported [15]. The crude extract obtained (175 g) was fractionated using a silica gel packed column, eluted with a gradient mixture of increasing polarity using hexane: ethyl acetate (10:0), (9:1), (7:3), (5:5). (3:7), (00:10) followed by ethyl acetate: methanol mixture (9:1), (8:2), (6:4), (4:6). A total of 51 fractions (500 ml each) was collected. Similar fractions after being sprayed with vanillin-sulphuric acid and Dragendorff reagents were combined to yield 18 main fractions.

Bioassay-guided fractionation

The 18 main fractions obtained from the MLE were subjected to bioassay-guided fractionation using the (MTT) reduction assay to identify fractions that contain cytotoxic compounds which could potentially be isolated by further sub-fractionation.

Isolation of cytotoxic compounds

The bioassay-guided fractionation of 18 fractions led to the identification of 3 fractions with significant cytotoxic activities. Based on their TLC profiles, 3 fractions (15, 16 and 17) were found to contain the same active compounds. Fraction 17 (0.6 g) was subjected to alumina oxide (Fluka AG, Buch SA) Fluka type 507C neutral packed column chromatography eluted with a gradient mixture of 1–10% dichloromethane/ methanol to yield pure compounds 1 (49.5 mg, 0.00028% dry weight) and 2 (22.2 mg, 0.00013% dry weight). The characterization and structural elucidation of compounds with significant cytotoxic effects were performed using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). The NMR spectra (1H and 13C NMR) were recorded in CDCl3 on a 200 MHz Varian Unity Inova spectrometer (Gemini 2000) housed at the Department of Chemistry (University of the Western Cape). The identification was completed after the comparison of the obtained data with previously published work.

MTT reduction assay

Viable cells were seeded at a density of 5 x104 cells/ml (100 μl/well) in 96-well plates and incubated in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air at 37°C for 24 h to form a cell monolayer. After 24 h, the cell culture medium was aspirated and 100 μl fresh medium containing varying concentrations of test compounds in log10 doses were added to the cells and the 96-well plates incubated for a further 24 h [16, 17].

After the 24 h treatments, 20 μl of 5 mg/ml MTT (prepared in PBS) was added to each well and the 96-well plates incubated for 3 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. The supernatant was aspirated and 150 μl of isopropanol added to each well after which the plate was gently shaken for 15 min to solubilize the formazan crystals and the absorbance was measured at 560 nm using a Glomax Multi Detection System (Promega, USA). The percentage inhibition of cell proliferation was calculated using the formula below and IC50 values computed by non-linear regression analysis of log dose-response sigmoidal curves using GraphPad Prism version 6.05 for Windows (GraphPad Software, La Jolla California USA, www.graphpad.com).

Cell cycle analysis

Cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well in 6-well plates and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C in a CO2 incubator to form a monolayer. The cells were treated for 12 and 24 h with the isolated compounds at concentrations equivalent to the IC50 concentrations (as determined by the MTT reduction assay). After treatment, the cells were detached with trypsin, washed in PBS and the cell pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of 1% paraformaldehyde and placed on ice for 30 min. Ethanol (70%, v/v) was slowly added to the cells while the sample was vortexed to reduce cell clumping. The cells were stored at − 20 °C for 48 h, after which the cells were recovered by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 10 min. The cell pellets were washed twice in PBS and then resuspended in 1 ml PBS containing 100 μg/ml RNase and 40 μg/ml propidium iodide. Cell cycle phase distribution was determined using a FACS Calibur Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The DNA content of 50,000 events was determined by ModFit software (Verity Software House, Topsham, ME), which provided histograms to evaluate the cell cycle distribution [14].

Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation assay

Cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 104 cells/well in black-walled 96-well microtiter plates and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C in a CO2 incubator to form a monolayer. The cells were treated for 12, 24 and 48 h with the isolated compounds at concentrations equivalent to the IC50 concentrations (as determined by the MTT reduction assay). Cell proliferation was determined using the ELISA-BrdU (5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine) chemiluminescence assay kit (Roche, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instruction, and expressed as the percentage DNA synthesis relative to the untreated control.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed by Two-Way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test and IC50 values estimated from non-linear regression curves were calculated using GraphPad Prism software version 6.05 for Windows (GraphPad Software, La Jolla California USA, www.graphpad.com).

Results

Bioassay-guided isolation of cytotoxic compounds

Crude extract (175 g) was subjected to silica gel packed column chromatography and yielded 18 fractions, three of which showed the same TLC profile and were cytotoxic. Fraction 17, one of the cytotoxic fractions (0.6 g), subjected to alumina oxide packed column chromatography, yielded 2 pure compounds tagged compounds 1 and 2 with 49.5 mg (0.00028% dry weight) and 22.2 mg (0.00013% dry weight), respectively. The NMR spectral data of the two compounds and their structures are presented in Table 1 and Fig. 1 respectively.

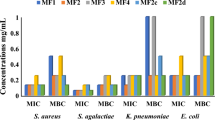

Cytotoxicity of isolated compounds

The cytotoxicity of isolated compounds 1 and 2 were tested on HT-29 (colon cancer), MCF-7 (breast cancer), HeLa (cervical cancer) and KMST-6 (non-cancerous fibroblast cells) as presented in Fig. 2. Table 2 shows the IC50 values and the selectivity index (SI) of the isolated compounds and standards. The cytotoxicity data showed that compound 1 induced significant cytotoxicity on HT-29 cancer cells compared with the other cancer cell lines with the lowest IC50 of 31.06 μM followed by MCF-7 (42.82 μM), HeLa (51.42 μM) and KMST-6 (102.95 μM). The cytotoxic effect of compound 1 is closely similar to that of compound 2. HT-29 was more sensitive to compound 2 with an IC50 of 22.36 μM followed by HeLa (46.17 μM), MCF-7 (52.69 μM) and KMST-6 (85.45 μM). The SI for compounds 1 and 2 (3.82 and 3.31, respectively) on HT-29 cells also confirms that this cell line was more sensitive to these two compounds. Cisplatin and doxorubicin showed significant indiscriminate cytotoxicity against cancer cells and the noncancerous cell line while the selectivity index imply that the isolated compounds were more selective towards cancer cells than the noncancerous cell line as opposed to the standard anticancer drugs with a lower selectivity index (Table 2).

Effect of isolated compounds on cell cycle progression

The effects of compounds 1 and 2 on cell cycle progression of cancer cells were evaluated by flow cytometry. The cells were treated with compounds 1 and 2 at concentrations equivalent to the IC50 values (Table 2) and a comparative analysis of the percentage cells in the G0/G1, S and G2/M cell cycle phases were performed at 12 and 24 h time points (Figure 3). In general, when the cells were treated with compounds 1 and 2, a significant increase in the percentage of cells in G0/G1 and G2/M phases was observed, which was accompanied by a simultaneous significant decrease in the percentage of cells in the S-phase. The results showed that the compounds induced a significant increase in cell populations in G0/G1 (P<0.01) and G2/M (P<0.001) phases with concomitant reduction in S-phase of HT-29 cell at both time points. A significant increase was observed in the G0/G1 phase with reduction in S-phase in HeLa cells treated with both compounds while significant decrease (P<0.01) in G2/M-phase was only observed at 24 h for compound 1. Both compounds induced significant (P<0.0001) increase and decrease in MCF-7 cell populations in G0/G1 phase and S-phase, respectively. The treatment of MCF-7 cells with compounds 1 and 2 resulted in a significant increase (P<0.001) in the G2/M-phase at 12 h while at 24 h significant increase induced by compound 2 reduced to (P<0.01) while compound 1 G2/M-phase increase was not significant.

Effects of the isolated compounds on DNA synthesis

The effects of the isolated compounds on DNA synthesis were tested using a BrdU chemiluminescent ELISA kit by treating the cells (HeLa, MCF-7 and HT-29) with the respective IC50 concentrations determined for the periods of 12, 24 and 48 h in relation to untreated control cells. Figure 4 shows that the two compounds significantly reduced DNA synthesis in all the cell lines. Compound 1 showed a significant reduction (P < 0.0088) between 24 and 48 h while compound 2 displayed significant reductions (P < 0.0001) in DNA synthesis between 12 and 24 h in HeLa cells. MCF-7 cells showed a significant reduction (P < 0.0030) in DNA synthesis when treated with compound 1 between 12 and 24 h while compound 2 significantly (P < 0.05) reduced the DNA synthesis between the 24 and 48 h exposure times. Compound 1 only showed a significant reduction (P < 0.0001) at 12 and 24 h treatments in HT-29 cells while compound 2 showed a significant reduction between 12 and 24 h (P < 0.05) and between 24 and 48 h (P < 0.001).

Discussion

Bioassay-guided isolation of compounds from the cytotoxic fractions of Holarrhena floribunda produced in two major aminosteroidal compounds identified as holamine and funtumine. These two steroidal alkaloids were identified based on their NMR spectra (1H and 13C) which were compared with the existing profiles in the literature [18]. Holamine is a major steroidal alkaloid from the genus Holarrhena which was identified in almost all the isolates generated from this genus [18, 19]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time the funtumine is isolated from Holarrhena floribunda leaves. This compound has been previously isolated from Holarrhena and Funtumia genera such as Holarrhene febrifuga, Holarrhena wulfsbergii and Funtumia latifolia [20, 21]. Alkaloids are widely distributed secondary metabolites derived from plants and well-known for their diverse pharmacological efficacies [22]. Fungicidal, anti-inflammatory and antibacterial activities of aminosteroids have been previously described [23, 24]. In addition, steroidal alkaloids are useful as starting materials for the synthesis of pharmaceuticals or important semi-synthetic drugs [25]. Holamine derivatives were used as starting material for the synthesis of immune stimulating aminopregnenes-I and active adjuvant anaphylactic glycinamide-II [26]. A funtumine derivate substituted with a guanylhydrazone moiety has previously been shown to interact selectively with the telomeric G-quadruplex in vitro [27]. Apart from being candidates for anticancer drug discovery, a previous study tends to suggest that steroidal alkaloids could also be used as starting materials and templates for the synthesis of anticancer drugs with desirable characteristics [27].

The cytotoxic activities of the isolated compounds were evaluated using the MTT reduction assay. It is a widely applied assay to evaluate cytostatic and/or cytotoxic potential of chemical and medicinal agents [28]. The cytotoxic effects of these compounds against cancer cell lines (HT-29, MCF-7 and HeLa) compared to non-cancerous fibroblast cells (KMST-6) as presented in Table 2 imply that they are significantly selective towards the cancer cells compared with the non-cancerous cells. The standard anticancer drugs (cisplatin and doxorubicin) are poorly selective between cancerous and non-cancerous cells when judged against the isolated compounds. The assay showed that HT-29 is more sensitive to the cytotoxic effects of both compounds 1 and 2 with IC50 values of 31.06 and 22.36 μM, respectively. The IC50 values for both compounds in HeLa, MCF-7 and KMST-6 cells were higher than 40 μM. This is the first cytotoxicity reported on the isolated compounds against this panel of cancer cells. The cytotoxic effects of compound 1 isolated from Holarrhena curtisii on HL-60 (human promyelocytic leukemia) and P-388 (murine lymphocytic leukemia) have been reported previously [18], while compound 2 displayed no cytotoxicity at a neuro-active concentration [29].

However, many anticancer agents are reported to play roles in cell cycle arrest and cell death [30]. Cell cycle transitions were evaluated in this study using flow cytometric analysis of propidium iodide (PI) stained cells. The results showed that compounds 1 and 2 induced a significant increase in the population of cells in G0/G1 phase and reductions in the S-phase population of cells treated with the corresponding IC50 concentration. Moreover, a significant increase was also observed in the population of cells in G2/M phase of HT-29 cells treated with compounds 1 and 2. The cell cycle results indicate that the compounds caused substantial arrest of cells in G0/G1 phase of the cell cycle. Cell cycle arrest at G0/G1 stage relates to the induction of cell cycle inhibitory proteins such as p16, p21, p27, which correlates with reduced expression of cyclins required for the G1 to S transition [31]. Liu et al. (2003) showed that terfenadine treatment induced upregulation of p53, p21/Cip1 and p27/Kip1 while simultaneous down regulation was observed for CDK2 and CDK4. Many anticancer drugs of natural origins such as paclitaxel, docetaxel, vinblastine and vincristine are known cell cycle inhibitors of the G2/M phase. Vinblastine and vincristine affect the G2/M phase of the cell cycle through inhibition of microtubule assembly while paclitaxel and docetaxel exert their actions through stabilization of microtubules, which induces the inhibition of microtubule disassembly and eventual arrest at G2/M phase of the cell cycle [32,33,34]. G0/G1 and G2/M arrest might be important pathways by which the isolated compounds induce cytotoxicity in cancer cells.

Agents that cause cell cycle arrest can be categorized into two classes: (1) those that directly inhibit DNA synthesis and (2) those that cause DNA damage leading to G1 or G2 arrest [35]. The effects of compounds 1 and 2 on DNA synthesis were evaluated using the cell proliferation ELISA chemiluminescent BrdU kit. The results showed that the two compounds significantly reduced cellular DNA synthesis within the duration of exposure to the IC50 levels in the respective cells. This result implies that the compounds can be placed in the category of agents that directly inhibit cellular DNA synthesis, which is consistent with the observed results in the cell cycle analysis with reduction of S-phase.

Conclusion

This study described the isolation of two steroidal alkaloids from the H. floribunda. Even though these compounds demonstrated relatively high IC50 values in the cancer cells tested in this study, they can still be considered good candidates for the development of anticancer drugs since they were shown to have selective anti-proliferative activities against cancer cells. Moreover, These compounds can also be used as drug leads for the development of other drugs or they can be used in combination with other antineoplastic drugs to compliment the therapeutic effects. However, more in vitro and in vivo mechanistic studies are required to understand the full potential of these compounds.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- BrdU:

-

Bromodeoxyuridine

- DMEM:

-

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- FBS:

-

Foetal bovine serum

- IC50 :

-

Half maximal inhibitory concentration

- MTT:

-

3-[4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- PBS:

-

Phosphate buffered saline

- TMS:

-

Tetramethylsilane

References

Newman DJ, Cragg GM. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the last 25 years. J Nat Prod. 2007;70(3):461–77.

Jung IL. Soluble extract from Moringa oleifera leaves with a new anticancer activity. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e95492.

van Wyk BE. A broad review of commercially important southern African medicinal plants. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;119(3):342–55.

Verpoorte R. Pharmacognosy in the new millennium: leadfinding and biotechnology. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2000;52(3):253–62.

Mukherjee PK. GMP for India system of medicine. New Delhi. In: PA: bus.Hori; 2003.

Liu YQ, Li WQ, Morris-Natschke SL, Qian K, Yang L, Zhu GX, Wu XB, Chen AL, Zhang SY, Nan X, et al. Perspectives on biologically active camptothecin derivatives. Med Res Rev. 2015;35(4):753–89.

Burkhill HM: Useful Plants of West Tropical Africa, vol. 1, Second edition edn. U.S.A: Roy Botanic Gardens, Kew; 2000.

Wiart C. Medicinal plants of Asia and the Pacific. Boca Raton: CRC Press/Taylor and Francis; 2006.

Siddiqui BS, Begum S, Siddiqui S, Lichter W. Two cytotoxic pentacyclic triterpenoids from Nerium oleander. Phytochemistry. 1995;39(1):171–4.

Keawpradub N, Eno-Amooquaye E, Burke PJ, Houghton PJ. Cytotoxic activity of indole alkaloids from Alstonia macrophylla. Planta Med. 1999;65(4):311–5.

Chang LC, Gills JJ, Bhat KP, Luyengi L, Farnsworth NR, Pezzuto JM, Kinghorn AD. Activity-guided isolation of constituents of Cerbera manghas with antiproliferative and antiestrogenic activities. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2000;10(21):2431–4.

Lhinhatrakool T, Sutthivaiyakit S. 19-nor- and 18,20-epoxy-cardenolides from the leaves of Calotropis gigantea. J Nat Prod. 2006;69(8):1249–51.

Abreu PM, Martins ES, Kayser O, Bindseil KU, Siems K, Seemann A, Frevert J. Antimicrobial, antitumor and antileishmania screening of medicinal plants from Guinea-Bissau. Phytomedicine. 1999;6(3):187–95.

Badmus JA, Ekpo OE, Hussein AA, Meyer M, Hiss DC. Antiproliferative and apoptosis induction potential of the Methanolic leaf extract of Holarrhena floribunda (G. Don). Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:756482.

Wong YH, Abdul Kadir H, Ling SK. Bioassay-guided isolation of cytotoxic Cycloartane triterpenoid glycosides from the traditionally used medicinal plant Leea indica. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:164689.

van de Loosdrecht AA, Beelen RH, Ossenkoppele GJ, Broekhoven MG, Langenhuijsen MM. A tetrazolium-based colorimetric MTT assay to quantitate human monocyte mediated cytotoxicity against leukemic cells from cell lines and patients with acute myeloid leukemia. J Immunol Methods. 1994;174(1–2):311–20.

Slater TF, Sawyer B, Straeuli U: Studies on succinate-tetrazolium reductase systems. Iii Points of Coupling of Four Different Tetrazolium Salts Biochim Biophys Acta 1963, 77:383–393.

Kam TS, Sim KM, Koyano T, Toyoshima M, Hayashi M, Komiyama K. Cytotoxic and leishmanicidal aminoglycosteroids and aminosteroids from Holarrhena curtisii. J Nat Prod. 1998;61(11):1332–6.

Dadoun HC. A.: leaf of alkaloids from Holarrhena congolensis Stapf (Apocynaceae) chemotaxonomic classification of the genus Holarrhen R. Brown. Plant Med Phytother. 1978;12:225–9.

Nelle SC, G.; cave, a.; Goutarel, R.: Stetoid alkaloids. Funtumine, holamine, bokitamine and androsta-1,4-dien-12β-ol-3,17-dione isolated from Halorrhena leaves. Sciences Chimiques 1970, 271:153–155.

Blanpin OQ. A. : comparative pharmacology of two alkaloids of steroid structure isolated from Funtumia latifolia, funtumine and funtumidine. Ann Pharm Fr. 1960;18:177–92.

Patel K, Gadewar M, Tripathi R, Prasad SK, Patel DK. A review on medicinal importance, pharmacological activity and bioanalytical aspects of beta-carboline alkaloid “Harmine”. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2012;2(8):660–4.

Griggs SC, King JA. Synthesis and preliminary anti-inflammatory evaluation of 17beta-amino-3beta-methoxy-5-androstene hydrochloride and related derivatives. J Pharm Sci. 1978;67(9):1215–8.

Szendi Z, Dombi G, Vincze I. Steroids, LIII: new routes to aminosteroids [1]. Monatsh Chem. 1996;127:1189–96.

Kanika P, Ravi BS, Danesh KP. Medicinal significance, pharmacological activites, and analytical aspects of solasodine: a concise report of current scientific literature. J Acute Disease. 2013;2013:92–8.

Torelli V, Benzoni J, Deraedt R. Derivatives of 3-amino-pregn-5-ene. In: Google Patents. 1984.

Brassart B, Gomez D, De Cian A, Paterski R, Montagnac A, Qui KH, Temime-Smaali N, Trentesaux C, Mergny JL, Gueritte F, et al. A new steroid derivative stabilizes g-quadruplexes and induces telomere uncapping in human tumor cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72(3):631–40.

Karikas GA. Anticancer and chemopreventing natural products: some biochemical and therapeutic aspects. Journal of BUON : official journal of the Balkan Union of Oncology. 2010;15(4):627–38.

Libor M, Alexander K, Zoila BR, Cristina ES. Effects of 3α-amino-5α-pregnan-20-one on GABAA receptor: synthesis, activity and cytotoxicity. Collect Czechoslov Chem Commun. 2004;69:1506–16.

Hadfield JA, Ducki S, Hirst N, McGown AT. Tubulin and microtubules as targets for anticancer drugs. Prog Cell Cycle Res. 2003;5:309–25.

Liu JD, Wang YJ, Chen CH, Yu CF, Chen LC, Lin JK, Liang YC, Lin SY, Ho YS. Molecular mechanisms of G0/G1 cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis induced by terfenadine in human cancer cells. Mol Carcinog. 2003;37(1):39–50.

Himes RH, Kersey RN, Heller-Bettinger I, Samson FE. Action of the vinca alkaloids vincristine, vinblastine, and desacetyl vinblastine amide on microtubules in vitro. Cancer Res. 1976;36(10):3798–802.

Schiff PB, Fant J, Horwitz SB. Promotion of microtubule assembly in vitro by taxol. Nature. 1979;277(5698):665–7.

Rakovitch E, Mellado W, Hall EJ, Pandita TK, Sawant S, Geard CR. Paclitaxel sensitivity correlates with p53 status and DNA fragmentation, but not G2/M accumulation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;44(5):1119–24.

Hung DT, Jamison TF, Schreiber SL. Understanding and controlling the cell cycle with natural products. Chem Biol. 1996;3(8):623–39.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Siya Mafunda for his assistance in the tissue culture laboratory and Ronnie Dreyer of University of Cape Town for helping with flow cytometry analysis.

Availability of data materials

The data generated are already at the University of the Western Cape, South Africa repository in the form of a dissertation.

Funding

This work was supported, in part, by the South African National Research Foundation and the University of the Western Cape.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BJA, EOE, AAH, MM and HDC participated substantially in the conception, design, methodology development, acquisition of data, statistical analysis and interpretation of data. BJA and EOE acquired the cell culture and compound isolation data and write the first draft of the manuscript. AAH participated and supervised the isolation of compounds, interpretation of data and revised the draft manuscript. MM and HDC participated in the acquisition of funding, supervision of cell culture analysis, analysis of data and revised the draft manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Badmus, J.A., Ekpo, O.E., Hussein, A.A. et al. Cytotoxic and cell cycle arrest properties of two steroidal alkaloids isolated from Holarrhena floribunda (G. Don) T. Durand & Schinz leaves. BMC Complement Altern Med 19, 112 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-019-2521-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-019-2521-9