Abstract

Background

Perinatal palliative care is an emerging branch of children’s palliative care. This study sought to better understand the pattern of antenatal referrals and the role of a specialist paediatric palliative care (PPC) team in supporting families throughout the antenatal period.

Methods

A single-centre retrospective chart review of all antenatal referrals to a quaternary children’s palliative care service over a 14-year period from 2007 to 2021.

Results

One hundred fifty-nine antenatal referrals were made to the PPC team over a 14-year period, with increasing referrals over time. Referrals were made for a broad spectrum of diagnoses with cardiac conditions (29% of referrals) and Trisomy 18 (28% of referrals) being the most prevalent. 129 referrals had contact with the PPC team prior to birth and 60 had a personalised symptom management plan prepared for the baby prior to birth. Approximately one third (48/159) died in utero or were stillborn. Only a small number of babies died at home (n = 10) or in a hospice (n = 6) and the largest number died in hospital (n = 72). 30 (19% of all referrals) were still alive at the time of the study aged between 8 months and 8 years.

Conclusions

Specialist PPC teams can play an important role in supporting families during the antenatal period following a diagnosis of a life-limiting fetal condition and demand for this service is increasing. A large proportion of the cases referred will not survive to the point of delivery and a number of babies may survive much longer than predicted. PPC teams can be particularly helpful navigating the uncertainty that exists in the antenatal period and ensuring that plans are made for the full spectrum of possible outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Since the world’s first children’s hospice opened in Oxfordshire in 1982, Paediatric Palliative Care (PPC) has rapidly become established as an important subspecialty within paediatrics, focusing on a multidimensional approach to the care of children and young people with life-limiting conditions [1]. Recent years have seen an expansion of PPC services into neonatal care [2] and the care of teenagers and young adults [3]. Extending palliative care into the antenatal period potentially represents the final frontier in the provision of children’s palliative care.

Increasingly sophisticated technology has enhanced our ability to accurately diagnose potentially life-limiting conditions during pregnancy. Improved prenatal screening coupled with increasing maternal age means that the fetal prevalence of conditions such as Trisomy 18 and 13 is increasing [4]. In countries where routine screening is in place, more than half of all congenital abnormalities are identified antenatally, including 74% of all major conditions [5]. Whilst a number of families opt for a termination of pregnancy following the diagnosis of a fetal anomaly [6], some elect to continue their pregnancy and providing adequate support to this cohort is important. Families who face the antenatal diagnosis of a life-limiting condition in their baby may be eligible for referral to a PPC service. However, we do not currently have an accurate picture of the number of these referrals and there is significant inequity in both the type and availability of PPC services across the UK, with a very small number of specialist PPC services and wide geographical variation in access to these services [7].

There have been a small number of studies worldwide reporting clinical experience of perinatal palliative care and only one published study from the UK [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25], summarised in Table 1. This literature suggests that there is considerable variability in the fetal conditions referred to palliative care and in the support that is offered to families. For clinicians in fetal medicine there can be a lack of clarity as to which conditions warrant an antenatal palliative care consultation and when is the right time to refer to PPC services [26].

We sought to review the experience at our centre over the last 14 years in order to better understand the pattern of antenatal referrals and the role that a specialist PPC team can play in supporting families in the antenatal period.

Methods

Antenatal referrals to the PPC team between 2007 and 2021 were identified using internal electronic database information. The Louis Dundas Centre for Children’s Palliative Care (LDC) at Great Ormond Street Hospital in London is a quaternary level specialist multidisciplinary PPC service. The LDC receives approximately 250 referrals every year from Greater London and South East England. Antenatal referrals come from 12 fetal medicine and obstetric centres across the region. There is no maternity unit at GOSH and all referrals are out-born. Antenatal support is usually offered by the PPC team via attendance at antenatal appointments and multidisciplinary meetings at other centres and via telephone consultations and home visits. The PPC team will typically work alongside local teams to make plans for the baby’s birth and postnatal care and this may involve preparing a Symptom Management Plan (SMP). Families are offered holistic support and we will usually involve the family’s local children’s hospice for additional support.

A retrospective review of both the maternal and, where relevant, child’s medical notes was carried out by three clinicians using a standardised electronic abstraction form with cross-verification to validate the data. We collected data on gestation at referral, fetal diagnosis, maternal ethnicity and religion, number and type of encounters with PPC, whether the family were previously known to PPC, whether a SMP was prepared prior to birth, date and location of death if applicable, whether a bereavement appointment was offered and age of surviving children (at time of final data collection in December 2022). Any discrepancies in data coding were reviewed jointly and discussed. Only data that had previously been collected as part of clinical care was extracted from the medical notes and only members of the patient’s direct clinical care team had access to the medical records. Data was anonymised with each patient being allocated a unique study code.

NHS Research Ethics Committee approval was not required for this study. Approvals were obtained from the Great Ormond Street Hospital Information Governance Team.

Results

One hundred fifty-nine antenatal referrals were received over the study period. Figure 1 illustrates a pattern of increasing referrals over time from 2 per year in 2007 to 36 per year in 2021.

Timing of referrals

The largest number of referrals were between 21 and 30 weeks gestation (74/159, 47%), followed by referrals between 30 and 35 weeks (54/159, 34%). A smaller proportion of patients were referred late (after 35 weeks, 25/159, 16%) or early (between 12 and 20 weeks, 5/159, 3%).

Four of the 159 families were previously known to the PPC team, due to having a previous child or children with a life-limiting condition.

Referral type

Referrals were made for a broad spectrum of fetal diagnoses with cardiac conditions (29% of all referrals) and Trisomy 18 (28% of all referrals) being the most prevalent. Table 2 illustrates the categories of fetal diagnoses for which antenatal referrals were made.

Contact with the PPC team

30/159 patients (19%) were referred but did not meet the PPC team (largely because of late referral, see discussion). The number of encounters for the remainder was 1 to 2 in 62% (98/159), 3 to 4 in 13% (21/159) and over 4 in 6% (10/159). Of the 129 families met by PPC prior to delivery, 87 had only face-to-face consultations, 35 had a mix of face-to-face and telephone consultations and 7 families had encounters by telephone only. 60 out of the 159 cases had a personalised SMP prepared for the baby prior to birth with guidance on how to manage potential symptoms using both pharmacological and non-pharmacological methods.

Age at death

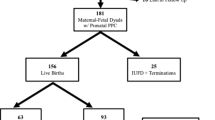

Figure 2 illustrates the age at death for the babies referred antenatally to the service. Of the 159 cases, 33 died in utero, 15 were stillborn, 28 died under 24 hours of age, 5 died between 24 and 48 hours, 12 died between 48 hours and 1 week of life, 15 died between 1 week and 4 weeks, 14 died at over 1 month old (5 with a diagnosis of Trisomy 18, 3 with cardiac disorders, 3 with abnormal brain/spinal cord development, 2 with holoprosencephaly and 1 with Trisomy 13), 30 were still alive at the time of the study and for 7 patients this data was missing. Table 3 illustrates the diagnoses and age at time of study for the 30 surviving children.

Place of death

Place of death was as follows (this excludes the 7 patients where age at death was unknown, 33 in utero deaths and 30 patients who were still alive): home (10/89), hospice (6/89), birth hospital (55/89), hospital transferred to (17/89) and unknown (1/89). Of the 10 children who died at home, 6 were over 1 month old when they died (age range 2 months to 6 years), 3 were between 1 week and 4 weeks old and 1 baby was over 48 hours old but less than 1 week old.

Discussion

A specialist PPC team can provide support to families navigating the challenging uncertainty of a life-threatening antenatal diagnosis, enabling them to make plans in anticipation of a range of possible outcomes. Parents who have received antenatal palliative care report positive experiences and describe the value of compassion from healthcare professionals, their babies being treated ‘as a person and not as a diagnosis’ and finding ways to honour their babies [27,28,29]. For some families the time they get to spend with their baby is very short, and extremely precious, and perinatal palliative care can help to ensure that families have no regrets about how they spend that time [30].

In this retrospective review we have demonstrated a striking increase in the number of referrals to PPC over the last 14 years from 1 to 2 per year to more than 30 per year. This likely reflects an increasing awareness of the role for specialist perinatal palliative care support [31]. The overall number of referrals, however, remains small and potentially represents only a small fraction of the eligible families. We do not have accurate data for the number of life-limiting conditions diagnosed in pregnancy each year in the UK but we do know that the live birth rate for London is approximately 120,000 live births each year [32] and that the birth prevalence for the 11 auditable conditions screened under the Fetal Anomaly Screening Programme (including anencephaly, HLHS, bilateral renal agenesis, lethal skeletal dysplasias and Trisomy 13 & 18) is 77 per 10,000 total births (live births and stillbirths) for London and the South East [6]. Even with conservative estimates this suggests that the number of life-limiting antenatal diagnoses each year in our referral region is likely to be in the hundreds. It may be that a number of these families are supported locally by fetal medicine and neonatal teams. Whilst we do not have this data for the UK context, a French study of prenatal decision-making processes found that it was very rare to have a palliative care specialist present in prenatal discussions (this occurred in only 2.8% of cases where perinatal palliative care was considered) [22].

The largest number of referrals came in the period between 21 and 30 weeks. This is likely to represent the fact that a number of congenital anomalies are first suspected at the fetal anomaly scan, which takes place at around 20 weeks gestation [6]. There were however a significant number of referrals in later gestation; 79 of the 159 referrals were received after 30 weeks. In practice referral to PPC usually only occurs if a family has elected to continue with the pregnancy, but there may arguably be a role for PPC support whilst parents remain in a decision-making phase or where there remains uncertainty around the baby’s prognosis. The significant variability observed in timing of referrals, and whether patients are referred at all, may indicate a need for clearer guidance.

As one of the largest published cohorts of antenatal referrals to PPC, the spectrum of conditions referred is also potentially informative. For example, we found a large number of referrals for fetuses with cardiac disease in our cohort (n = 46). From 2020 onwards it has been the policy of our fetal cardiology team to refer all single ventricle patients to PPC. However even prior to this policy, the majority of referrals involved diagnoses of congenital heart disease or cardiac anomalies associated with features of Trisomy 13 or Trisomy 18, all of which are reviewed in fetal cardiology clinic. Our population may be somewhat unique given the presence of three paediatric cardiac centres in the London region, but the large number of antenatal referrals with cardiac disease nevertheless points to an important role for joint working between fetal cardiology and PPC teams in the future.

Within this study, 30 of the referrals did not meet the PPC team before birth and in most cases, this was because the baby either died in utero or the referral was received late in pregnancy and the baby delivered before a first meeting could be arranged. In 2 cases, it was documented that the family declined antenatal input from PPC. This highlights the importance of equipping all healthcare professionals working in antenatal care with foundational knowledge in palliative care and the communication skills necessary to handle these sensitive consultations.

Approximately half of the cases who were met by the PPC team had a personalised SMP prepared (60/129) for the baby before birth which gave guidance on how to manage potentially distressing symptoms such as pain, breathlessness and excessive secretions. These plans include suggestions for symptom management using non-pharmacological techniques as well as recommended doses for medications on a dose per kg basis until a birth weight is available. Our anecdotal experience is that medical teams value having access to SMPs in advance of a baby’s birth and that they can be a useful basis for discussion with parents around what symptoms they may expect to see in their baby. There is however an important lack of data in the literature around the prevalence of symptoms early after delivery and the value of SMPs in perinatal palliative care, which warrants further attention.

Only a very small number of babies in this cohort died at home (n = 10) or at a hospice (n = 6) and the largest number of babies died in hospital (n = 72). Those children who died at home tended to be older, with no babies who died at less than 48 hours old making it home. Whilst we do not have data on parental preference for place of death for these cases, there are recognised barriers to both offering and achieving a choice of place of death for seriously ill neonates [33]. Further research would be helpful to address whether choice of place of death could be more readily explored during the advance care planning process. In our study 28/159 babies died within 24 hours suggesting that in specific cases where the risk of early postnatal demise is particularly high, parental counselling around preferred place of death may need to take this into account.

A large number of babies (48/159) in our cohort died either in utero or during delivery which is reflective of the liveborn rate observed in previous studies (Table 1). Not knowing whether a fetus will survive to birth or not can be immensely difficult for both families and health care professionals and the palliative care team may play a role in navigating this space of uncertainty. The process of planning a baby’s management after birth can be supportive and therapeutic in and of itself, even if the baby does not survive to the point of delivery [34].

There was a large group of surviving babies in our cohort (n = 30). Aside from one child with Trisomy 18 who was 8 years old at the time of this study and one child with arthrogryposis (5 years old) these surviving babies all fell into two categories; either congenital heart disease (including Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome) or severe Central Nervous System abnormalities (including holoprosencephaly). This points to the important role that palliative care teams can play in ensuring that parallel planning takes place for these families. Parallel planning - planning for life while also planning for deterioration or death [35] - allows families to be prepared for the worst possible outcome but also simultaneously counselled about plans for if their baby survives. Indeed, it can sometimes be incredibly difficult for families to adjust to the reality of bringing their baby home if they have not been told about the possibility of their baby surviving. In these cases, it is also vital that appropriate expertise is sought from the relevant specialists, such as fetal cardiologists and neurosurgeons. For some of these children, palliative care will be offered alongside curative treatment, or treatment aimed at significantly prolonging life.

Antenatal counselling and support is provided by large multi-disciplinary teams, which include midwives, fetal medicine specialists, obstetricians, neonatologists and paediatric sub-specialists, and equipping all members of the team with the confidence to deliver elements of PPC is important. Professionals working in fetal medicine and paediatrics have themselves identified the need for integrated PPC services that take a multi-professional approach and which incorporate education and training for all health care professionals involved [36, 37].

Finally, as prenatal imaging techniques and genetic screening continue to improve, establishing robust provision of antenatal palliative care will become ever more important as more families face increasingly complex decisions. Importantly, NICE identified perinatal palliative care as one of five key research recommendations in their 2016 guideline on ‘End of life care for infants, children and young people with life-limiting conditions’ [38]. There is a need for further prospective research looking at the experience of families following the diagnosis of a life-limiting condition during pregnancy, the support they are currently offered and the role that PPC services can play in this support.

Study limitations

This was a retrospective chart review and was therefore reliant on the accuracy of the data available in the medical notes. We attempted to look at other features of the antenatal referrals including parental ethnicity and religion and bereavement follow-up but unfortunately a lot of this data was missing, making it too incomplete to usefully interpret. We have also not captured here those babies diagnosed with a life-limiting condition antenatally but who were not referred to the PPC team until after birth. This study also lacks any qualitative assessment of the experience of parents (as well as that of health care professionals), which is crucial in understanding the impact of the support offered to families by the PPC team.

Conclusions

Specialist PPC teams can play an important role in supporting families during the antenatal period following a diagnosis of a life-limiting fetal condition and demand for this service is increasing. The range of outcomes for the babies illustrated in this study underlines the uncertainty that exists for families in the antenatal period and identifies a crucial role for palliative care teams in facilitating meaningful parallel planning in conjunction with the appropriate disease specialists.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AVSD:

-

Atrioventricular septal defect

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- HLHS:

-

Hypoplastic left heart syndrome

- LDC:

-

Louis dundas centre for children’s palliative care

- PPC:

-

Paediatric palliative care

- SMP:

-

Symptom management plan

- TOP:

-

Termination of pregnancy

- VSD:

-

Ventricular septal defect

References

Hain R, Heckford E, McCulloch R. Paediatric palliative medicine in the UK: past, present, future. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97(4):381–4.

Marc-Aurele KL, English NK. Primary palliative care in neonatal intensive care. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41(2):133–9.

Chambers L. Stepping Up: A guide to developing a good transition to adulthood for young people with life-limiting and life-threatening conditions [Internet]. 2015. [cited 2023 Jan 9]. Available from:https://www.togetherforshortlives.org.uk/resource/transition-adult-services-pathway/.

Irving C, Richmond S, Wren C, Longster C, Embleton ND. Changes in fetal prevalence and outcome for trisomies 13 and 18: a population-based study over 23 years. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;24(1):137–41.

Bijma HH, van der Heide A, Wildschut HIJ. Decision-making after ultrasound diagnosis of fetal abnormality. Reprod Health Matters. 2008;16(31 Suppl):82–9.

Public Health England. National congenital anomaly and rare disease registration service: Congenital anomaly statistics 2019 [Internet]. [cited 2022 Nov 30]. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1021335/NCARDRS_congenital_anomaly_statistics_report_2019.pdf.

Mitchell S, Morris A, Bennett K, Sajid L, Dale J. Specialist paediatric palliative care services: what are the benefits? Arch Dis Child. 2017;102(10):923–9.

Calhoun BC, Napolitano P, Terry M, Bussey C, Hoeldtke NJ. Perinatal hospice. Comprehensive care for the family of the fetus with a lethal condition. J Reprod Med. 2003;48(5):343–8.

D’Almeida M, Hume RF, Lathrop A, Njoku A, Calhoun BC. Perinatal Hospice: Family-Centered Care of the Fetus with a Lethal Condition. J Am Physicians Surg. 2006;11(2):4.

Breeze ACG, Lees CC, Kumar A, Missfelder-Lobos HH, Murdoch EM. Palliative care for prenatally diagnosed lethal fetal abnormality. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2007;92(1):F56–8.

Leong Marc-Aurele K, Nelesen R. A five-year review of referrals for perinatal palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(10):1232–6.

Kukora S, Gollehon N, Laventhal N. Antenatal palliative care consultation: implications for decision-making and perinatal outcomes in a single-Centre experience. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2017;102(1):F12–6.

Bétrémieux P, Druyer J, Bertorello I, Huillery ML, Brunet C, Le Bouar G. Antenatal palliative plan following diagnosis of fetal lethal condition: Rennes teaching hospital experience. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2016;45(2):177–83.

Hostalery L, Tosello B. Outcomes in continuing pregnancies diagnosed with a severe fetal abnormality and implication of antenatal neonatology consultation: a 10-year retrospective study. Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2017;36(3):203–12.

Bourdens M, Tadonnet J, Hostalery L, Renesme L, Tosello B. Severe fetal abnormality and outcomes of continued pregnancies: a French multicenter retrospective study. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21(10):1901–10.

Marc-Aurele KL, Hull AD, Jones MC, Pretorius DH. A fetal diagnostic center’s referral rate for perinatal palliative care. Ann Palliat Med. 2018;7(2):177–85.

Pfeifer U, Gubler D, Bergstraesser E, Bassler D. Congenital malformations, palliative care and postnatal redirection to more intensive treatment - a review at a Swiss tertiary center. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018;31(9):1182–7.

McMahon DL, Twomey M, O’Reilly M, Devins M. Referrals to a perinatal specialist palliative care consult service in Ireland, 2012–2015. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2018;103(6):F573–6.

Kamrath HJ, Osterholm E, Stover-Haney R, George T, O’Connor-Von S, Needle J. Lasting legacy: maternal perspectives of perinatal palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(3):310–5.

Tucker MH, Ellis K, Linebarger J. Outcomes following perinatal palliative care consultation: a retrospective review. J Perinatol. 2021;41(9):2196–200.

Doherty ME, Power L, Williams R, Stoppels N, Grandmaison DL. Experiences from the first 10 years of a perinatal palliative care program: a retrospective chart review. Paediatr Child Health. 2021;26(1):e11–6.

de Barbeyrac C, Roth P, Noël C, Anselem O, Gaudin A, Roumegoux C, et al. The role of perinatal palliative care following prenatal diagnosis of major, incurable fetal anomalies: a multicentre prospective cohort study. BJOG. 2022;129(5):752–9.

Buchholtz S, Fangmann L, Siedentopf N, Bührer C, Garten L. Perinatal palliative care: additional costs of an Interprofessional service and outcome of pregnancies in a cohort of 115 referrals. J Palliat Med. 2022;11

Tewani KG, Jayagobi PA, Chandran S, Anand AJ, Thia EWH, Bhatia A, et al. Perinatal palliative care service: developing a comprehensive care package for vulnerable babies with life limiting fetal conditions. J Palliat Care. 2022;37(4):471–5.

Buskmiller C, Ho S, Chen M, Gants S, Crowe E, Lopez S. Patient-centered perinatal palliative care: family birth plans, outcomes, and resource utilization in a diverse cohort. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2022;4(6):100725.

Stenekes S, Penner JL, Harlos M, Proulx MC, Shepherd E, Liben S, et al. Development and implementation of a survey to assess health-care Provider’s competency, attitudes, and knowledge about perinatal palliative care. J Palliat Care. 2019;34(3):151–9.

Todorovic A. Palliative care is not just for those who are dying. BMJ. 2016;15(353):i2846.

Wool C, Kain VJ, Mendes J, Carter BS. Quality predictors of parental satisfaction after birth of infants with life-limiting conditions. Acta Paediatr. 2018;107(2):276–82.

Côté-Arsenault D, Denney-Koelsch EM, McCoy TP, Kavanaugh K. African American and Latino bereaved parent health outcomes after receiving perinatal palliative care: a comparative mixed methods case study. Appl Nurs Res. 2019;50:151200.

Dickson G. A Perinatal Pathway for Babies with Palliative Care Needs, 2nd edition [Internet]. 2019. Mar [cited 2023 Jan 9]. Available from:https://www.togetherforshortlives.org.uk/resource/perinatal-pathway-babies-palliative-care-needs/.

Marc-Aurele KL. Decisions parents make when faced with potentially life-limiting fetal diagnoses and the importance of perinatal palliative care. Front Pediatr. 2020;22(8):671.

Office for National Statistics. Nomis - Official Census and Labour Market Statistics. In: Live births in England and Wale: birth rates down to local authority areas [Internet]. [cited 2022 Dec 12]. Available from: https://www.nomisweb.co.uk/datasets/lebirthrates.

Craig F, Mancini A. Can we truly offer a choice of place of death in neonatal palliative care? Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;18(2):93–8.

Cortezzo DE, Ellis K, Schlegel A. Perinatal palliative care birth planning as advance care planning. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:556.

Jack BA, Mitchell TK, O’Brien MR, Silverio SA, Knighting K. A qualitative study of health care professionals’ views and experiences of paediatric advance care planning. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;13(17):93.

Flaig F, Lotz JD, Knochel K, Borasio GD, Führer M, Hein K. Perinatal palliative care: a qualitative study evaluating the perspectives of pregnancy counselors. Palliat Med. 2019;33(6):704–11.

Tosello B, Dany L, Bétrémieux P, Le Coz P, Auquier P, Gire C, et al. Barriers in Referring Neonatal Patients to Perinatal Palliative Care: A French Multicenter Survey. 2015. [cited 2019 Nov 3]; Available from:https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0126861&type=printable.

NICE. End of life care for infants, children and young people with life-limiting conditions: planning and management [Internet]. 2016. [cited 2023 Jan 10]. Available from:https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng61/resources/end-of-life-care-for-infants-children-and-young-people-with-lifelimiting-conditions-planning-and-management-pdf-1837568722885.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge all of the families included in this study.

Funding

This research was funded in part, by the Wellcome Trust (Grant numbers 224744/Z/21/Z and 203132/Z/16/Z). The funders had no role in the preparation of this manuscript or the decision to submit for publication.

For the purpose of open access, the author(s) has applied a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising.

All research at Great Ormond Street Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health is made possible by the NIHR Great Ormond Street Hospital Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SB was responsible for the concept and design of the study, data collection, data analysis and drafting and revising the manuscript. GB and NC were responsible for the concept and design of the study, data collection, data analysis and revising the manuscript. FC and DW were responsible for data analysis and revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study formed part of a service evaluation and NHS Research Ethics Committee approval was not required. Approvals were obtained from the Great Ormond Street Hospital Information Governance Team. Only data that had previously been collected as part of clinical care was extracted from the medical notes and only members of the patient’s direct clinical care team had access to the medical records. Informed consent was waived as there was no data collected over and above the existing medical records. Data was anonymised such that individual patients were not identifiable. All experiments were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations (e.g. Declaration of Helsinki).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Bertaud, S., Brightley, G., Crowley, N. et al. Specialist perinatal palliative care: a retrospective review of antenatal referrals to a children’s palliative care service over 14 years. BMC Palliat Care 22, 177 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-023-01302-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-023-01302-5