Abstract

Background

Depression is prevalent in people with very poor prognoses (days to weeks). Clinical practices and perceptions of palliative physicians towards depression care have not been characterised in this setting. The objective of this study was to characterise current palliative clinicians’ reported practices and perceptions in depression screening, assessment and management in the very poor prognosis setting.

Methods

In this cross-sectional cohort study, 72 palliative physicians and 32 psychiatrists were recruited from Australian and New Zealand Society of Palliative Medicine and Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists between February and July 2020 using a 23-item anonymous online survey.

Results

Only palliative physicians results were reported due to poor psychiatry representation. Palliative physicians perceived depression care in this setting to be complex and challenging. 40.0% reported screening for depression. All experienced uncertainty when assessing depression aetiology. Approaches to somatic symptom assessment varied. Physicians were generally less likely to intervene for depression than in the better prognosis setting. Most reported barriers to care included the perceived lack of rapidly effective therapeutic options (77.3%), concerns of patient burden and intolerance (71.2%), and the complexity in diagnostic differentiation (53.0%). 66.7% desired better collaboration between palliative care and psychiatry.

Conclusions

Palliative physicians perceived depression care in patients with very poor prognoses to be complex and challenging. The lack of screening, variations in assessment approaches, and the reduced likelihood of intervening in comparison to the better prognosis setting necessitate better collaboration between palliative care and psychiatry in service delivery, training and research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Depression is a distressing condition for people with advanced life-limiting illnesses. It can reduce the quality-of-life of those affected and others around them, exacerbate physical suffering and worsen psycho-existential distresses [1,2,3,4]. Not only does depression impact patient engagement with their nearest supporters, but depression can also negatively affect clinicians’ ability to deliver care [1, 5]. Despite its prevalence, there is evidence that depression has been under-assessed and, even when recognised, under-managed in the palliative care setting [6,7,8,9].

In the palliative care population, there is a sub-group of patients with very poor prognoses defined as an estimated life expectancy in the range of days to weeks. This sub-group is characterised by a high degree of frailty, often with significant symptom burden and rapidly declining functional status [10, 11]. The frailty, symptom burden (e.g. fatigue, confusion, and dysphagia), and limited time for interventions to take effect can make depression assessment, psychotherapies and administration of typical antidepressants (e.g. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors [SSRIs] and Serotonin Noradrenaline Reuptake Inhibitors [SNRIs]) challenging for clinicians [12,13,14]. Subsequently, clinicians’ approaches to depression assessment and management for these people might differ from palliative patients with better prognoses.

While previous studies of clinicians’ approaches to depression assessment and management in the general palliative care population have been done in Australia and the United Kingdom, palliative physicians’ and psychiatrists’ approaches to depression care specifically for people with very poor prognoses have not been explored [8, 9, 15].

Methods

Aim

This study aimed to characterise current Australasian palliative clinicians’ (palliative physicians and psychiatrists) reported practices and perceptions in depression assessment and management for palliative patients with very poor prognoses, including identifying barriers to optimising depression care in this context.

Study Design

This was a cross-sectional cohort study using an online survey.

Respondents

Eligible respondents were: 1. current members of the Australian and New Zealand Society of Palliative Medicine (ANZSPM), the largest Australasian professional society for medical practitioners interested in palliative medicine, including specialist physicians (e.g. palliative physicians and renal physicians), general practitioners, and radiation oncologists; and 2. psychiatry fellows and trainees registered with the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP).

Survey

The anonymous online survey (Additional file 1) used the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) platform. It contained branching logic with a maximum of 23 questions (four multiple response questions and 19 single response questions) for each respondent, tailored according to the respondent’s self-identified primary discipline (palliative medicine or psychiatry) and previous encounters with patients with very poor prognoses. It explored the domains of depression screening, assessment, management and integration between psychiatry and palliative care services for patients with very poor prognoses based on extrapolation from the general palliative care literature and investigators’ clinical experiences [9, 14, 16, 17]. Particularly, interventions that might produce rapid antidepressant effects in the very poor prognosis setting such as adjunct antipsychotics, psychostimulants, ketamine and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) were explored [18,19,20,21]. The survey contained two opened-ended questions asking for perceived challenges or barriers to effective assessment and management of depression in patients with very poor prognoses. To increase feasibility, validity and reliability, the survey questions were developed by the investigator panels consisting of clinical academic experts from palliative care and psychiatry and piloted with four palliative physicians without needing to further modify the questionnaire. The survey took, on average, 8 minutes to complete, on piloting.

Recruitment

The survey link was first distributed by the professional bodies to members on the 25th of Feb 2020 (ANZSPM) and the 1st of May 2020 (RANZCP). Due to the restrictions of the survey dissemination policies, capacity for sending reminder emails was limited: for ANZSPM, only one reminder email was sent after 2 weeks; for RANZCP, no reminder email could be sent to the entire cohort but one reminder email was sent to the College Faculty of Consultation Liaison, after 6 weeks (12th of June 2020). Apart from the RANZCP mass cohort distribution, where the survey link was distributed as part of an electronic newsletter (Psyche), survey links were contained within the email distributed by the professional bodies (ANZSPM and RANZCP College Faculty of Consultation Liaison). The survey was closed on the 31st of Jul 2020. No financial incentives were offered to respondents.

Data Analysis

Quantitative data were expressed as the number of respondents (percentage) and analysed using a IBM SPSS Statistics 26 [22].

Responses to the two open-ended items were analysed independently by two investigators (WL and MD) using conventional qualitative content analysis, which aligns with the aims of this study [23, 24]. WL was a palliative care physician who has clinical experience as a psychiatry resident, and MD was an experienced qualitative health researcher. Codes were developed inductively through careful reading of the data and sorted into categories of related material in NVivo 12. Categories were refined, defined, and subcategories developed through analyst discussion until consensus was achieved [23, 24]. Quantification of responses within subcategories was performed using NVivo 12 [25].

Results

Completed surveys were obtained from 110 individuals: 79 responses out of 522 members of ANZSPM (15.1%); and 31 out of 6655 RANZCP members (0.5%). Of the 110 responses, 72 respondents identified as having the primary specialty of palliative medicine and 32 with psychiatry. Due to the lack of response from the RANZCP members and hence the lack of representation of the Australasian psychiatry cohort, only results from those who identified themselves primarily as palliative physicians (n = 72) were reported (Table 1).

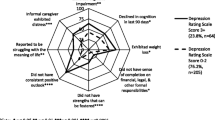

Participating clinicians were mainly specialist and fellows (73.6%); female (75.0%); aged 31–60-year-old (87.4%); primarily working in Australia (76.4%); graduated more than 10 years ago (88.9%); and working ≥20 clinical hours per week (90.2%). Most clinicians (n = 70; 97.2%) reported having encountered depression in people with very poor prognoses.

The majority (n = 42; 58.3%) of all palliative physicians reported that they screen for depression in general palliative care patients, while only 40.0% (n = 28 out of 70) of clinicians encountering patients with very poor prognoses reported screening for depression.

Among physicians who might screen for depression (answered “yes” or “depends”) in general palliative care patients, the primary screening method reported was clinical interview (n = 53; 93.0%), followed by asking the family/carers (n = 40; 70.2%), asking other health professionals involved in the care (n = 37; 64.9%), and the use of screening tools (n = 27; 47.4%). For the very poor prognoses group, while 68.6% (n = 48) of physicians reported no difference in the way of screening compared to the general palliative population, 18.6% (n = 13) reported a “difference”: taking a more reactive rather than proactive approach; being briefer in assessment; relying more on objective information sources; and emphasising less on somatic symptoms. Among those who reported to use screening tools (n = 27), the most commonly used tools was the ultra-short two-items questionnaire (n = 14; 51.8%) followed by a single-item questionnaire (n = 5; 18.5%) (e.g. asking “Are you depressed” and/or “Have you had little interest or pleasure in doing things”). Only one respondent reported to use Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

For depression assessment, at least 80% of physicians would ascertain whether the depression episode is first or recurrent during assessment, regardless of whether the prognoses is very poor or not. All physicians who have encountered depressed patients with very poor prognoses have experienced uncertainty regarding the cause of depression. Most palliative physicians (n = 56; 80.0%) would treat the depressed mood despite the uncertain cause. The primary sources of assistance sought by palliative physicians in this context were from psychiatry (n = 33; 47.1%) and psychology (n = 29; 41.4%).

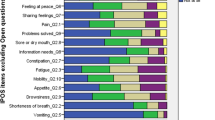

For depression somatic symptom assessment, the majority (n = 37; 51.4%) of physicians reported including somatic symptoms in the general palliative care patients while excluding somatic symptoms in the sub-group with very poor prognoses (n = 29; 41.4%). Notably, in the setting of very poor prognoses, 30.0% (n = 21) of physicians reported “depends”: whether the somatic symptoms could be attributable to the nature of the terminal illnesses and associated interventions on an individual basis; and that somatic symptoms were still valuable to be considered in the “overall picture” of the patient.

For various treatment approaches for major depressive disorder in the setting of very poor prognoses (Table 2), most physicians reported using non-pharmacological approaches (n = 64; 91.4%), followed by the use of typical antidepressants (n = 63; 90%). When comparing the likelihood of using various depression interventions in the very poor prognoses sub-group as compared to the general palliative care cohort, the majority of physicians reported: no difference or less likely in using non-pharmacological interventions (both groups: n = 26; 37.1%), and less likely to use typical antidepressants (n = 36; 51.4%). For ECT in the setting of very poor prognosis, 72.9% (n = 51) and 14.3% (n = 10) of physicians reported to not use or less likely to use it respectively. There were bimodal distributions with the highest prevalence of “I don’t use” followed by “more likely to use” for treatment options of: atypical antipsychotics (n = 26; 37.1% - “I don’t use” and n = 20; 28.6% - “more likely”); benzodiazepines (n = 28; 40.0% - “I don’t use” and n = 24; 34.3% - “more likely”); and novel medication/experimental trials (n = 49; 70% - “I don’t use” and n = 12; 17.1% - “more likely”). Due to technical issues in the online survey platform, the psychostimulant item was initially not available for the first 28 participants, leading to the large proportion of non-response (n = 27; 38.6%) for this item. Despite this limitation, among the responders, the majorities answered “I don’t use” or “more likely to use” (both groups n = 18 out of 43; 41.9%).

For service linkage with psychiatry (Table 3), the majority of palliative physicians reported to request for psychiatry input in an interval of monthly or longer (n = 41; 56.9%) and being requested by psychiatry for palliative care input yearly or longer (n = 26; 36.1%). Two-thirds of the palliative physicians (n = 48) thought contract frequency with psychiatry should be more frequent.

Sixty-six respondents (91.7%) provided answers to the open-ended questions regarding key challenges or barriers to effective assessment and management of depression in palliative care patients with very poor prognoses. Respondents commented on the complexity of the clinical situation with interaction between physical, psychosocial, and spiritual dimensions. Reported key challenges and barriers are listed in Table 4, categorised under the domains of patient, clinician, health system, literature and society. On quantifying the various domain subcategories (Table 4), the three most frequently reported barriers were: the lack of therapeutic options that are rapidly effective (77.3%); the perceived frailty, burden and intolerance of depression assessment and management on the patient (71.2%); and the complexity in differentiating the symptoms of terminal illness from the somatic symptoms of depression (53.0%).

Discussion

This is the first study that captures palliative physicians’ practices and perceptions regarding depression care specifically in people with very poor prognoses of only days to weeks. As demonstrated by the survey, encountering depression in patients with very poor prognoses was common to palliative physician. However, despite the high prevalence of depression (up to 50%) in this population and the frequency of clinical encounters, only 40% of clinicians reported to screen for depression, with all clinicians reported to have experienced uncertainty when assessing the cause of depression [26]. This is reflected by the current study finding of the perceived challenging complexity of depression care in the very poor prognosis setting by clinicians. According to the literature, this complexity may be contributed to by the interplay of various domains of challenges reported in Table 4: 1) Patients’ frailty, co-existing symptom burden and associated end-of-life issues when time for intervention effects is poor [9, 14]; 2) Clinicians’ self-perceived limitations of psychiatry skills in the palliative care setting and incompetence in diagnostic differentiation [9, 27]; 3) Health system’s inadequacy of resources and access to required interventions in the local health services (e.g. mental health services) [8, 9]; 4) Heterogeneity of depression concept and the lack of evidence to guide practice in the literature for this context [26, 28]; and 5) Unsupportive societal attitudes that prevents the optimisation of depression care (e.g. stigma of mental illnesses, the “normalisation” or “acceptance” of depression at the end-of-life) [29, 30]. Each of these domains warrant future exploration for potential solutions to better optimise depression care in this setting.

Palliative physicians reported to less likely screen for depression and have ambivalence in depression assessment methods (e.g. approach to somatic symptoms of depression) in the very poor prognosis setting compared to the better prognosis setting. Diagnosing depression in the setting of very poor prognosis can be challenging as the symptoms of terminal illnesses (e.g. fatigue and weight loss) can confound the somatic symptoms of depression [17]. Importantly, this study shows that while clinicians may perceive somatic symptoms of depression to be less useful in depression diagnosis, somatic symptoms are still important to be considered during the overall depression assessment as they can affect the appropriateness of intervention choices. It may be desirable for clinicians to be trained with the various approaches to somatic symptoms such as Endicott Criteria to enable better diagnostic differentiation and depression assessment [31]. While they reported to generally intervene less in this setting (compared to patients with better prognoses), it is worth noting the bimodal distributions of clinicians not-using and more-likely-to-use certain non-typical pharmacological interventions (e.g. psychostimulants, atypical antipsychotics, benzodiazepines and novel medications such as ketamine) that have more augmentation and rapid-onset potentials than typical antidepressants [18,19,20, 32]. This may reflect clinicians’ attitudes where clinicians who were trained and aware of how to leverage the potential benefits of these non-typical treatments while minimising intolerance were more likely to embrace their use. Whereas, clinicians who lacked training or resources for these treatments did not tend to use them. Comparable to the study findings in the United Kingdom primary care and palliative settings, inadequately equipped clinicians may have a nihilistic attitude and ambivalence towards depression screening and assessment [8, 29, 30]. The low reported usage of ECT was likely related to clinicians perceiving the intervention to be over-burdensome for people with very poor prognoses [33]. Subsequently, palliative physicians and their multidisciplinary team members should be trained with the necessary skills to screen, assess, and administer first-line rapidly effective depression interventions in low-burden manners [34]. This may be facilitated by better linkage and integration of the psychiatry services into the palliative care services [17, 35].

Similar to the United States palliative physician cohort, near 70% of current survey’s respondents expressed desires for better collaboration with the psychiatry services [36]. At the clinical and health service levels, some strategies to improve palliative care and psychiatry collaboration might include: integrative multidisciplinary team [15, 36,37,38]; joint development of a tiered-referral model tailored to local health service needs [39]; and integrated clinician training via workshops and experiential training [35, 37, 38]. For research, palliative care and psychiatry researchers must collaborate to address barriers to the currently limited evidence base. On top of the barriers to depression care processes identified in this survey, other challenges include the effects of depression and terminal illnesses on participants’ ability to consent and engage with research activities, and the ethical concerns of trial participants receiving potentially ineffective therapies [40, 41]. There is a need for integrated palliative care and psychiatry research that explores appropriate depression screening and assessment strategies and potentially rapidly effective interventions using feasible and inclusive trial designs in the very poor prognosis setting (e.g. n-of-1, Bayesian response-adaptive-randomisation, or well-designed prospective case-controlled studies) [26, 35, 42]. Developing consensus approaches between palliative care and psychiatry via Delphi and updating the existing guideline based on the currently limited evidence to guide depression care specifically for people with very poor prognoses need to be considered [16, 17]. Overall, better collaboration between palliative care and psychiatry is urgently required, optimising timely access to needed interventions, complementing the shortfalls of both disciplines, and ultimately improving care to affected patients [35, 37, 43].

Limitations

This study had low response rates, especially from the psychiatry cohort. These low rates were likely contributed by the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to clinicians focusing on COVID-19 related activities rather than non-COVID-19 research. It was possible that psychiatrists lacked interest or perceived a lack of relevance towards this topic due to their infrequent engagement with palliative care [35]. The low sample size limited the power for detailed subgroup analyses. The current survey did not include non-physician palliative clinicians (e.g. nurses and pastoral care) or psychologists. Furthermore, as the respondents were recruited only from the Australasia setting, the survey findings may not be generalised to non-Australasian contexts. Intrinsic to the study methodology, there was a risk of reporting bias where the reported practices deviate from the true practices. For depression interventions, various non-pharmacological interventions (e.g. supportive psychotherapy versus cognitive therapy) were not individually explored. Due to a technical fault, the survey question exploring psychostimulant use was initially unavailable to the first 28 ANZSPM respondents. Despite these limitations, the data collected still helped inform current practices and perceptions of some palliative physicians in Australasia. Lastly, while the prevalence data in Table 4 offered valuable insight into the prevailing perceived key barriers or challenges of depression care in the very poor prognosis setting among respondents, the prevalence data did not necessarily reflect the level of importance or influence of certain subcategories over another in optimising depression care. In fact, the domain subcategories reported less often such as the heterogeneity of depression concept and unsupportive societal attitudes might reflect that many clinicians were not cognisant of these topics, thus suggesting the need for improving awareness of these issues.

Conclusions

Palliative physicians perceived depression care in people with very poor prognoses to be complex and challenging. The lack of screening, heterogeneity in the depression assessment, and the generally reduced likelihood of intervening for depression in the very poor prognosis setting compared to that of better prognosis highlighted the need for better collaboration between palliative medicine and psychiatry in health service delivery, clinician training, and research.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Block SD. Assessing and managing depression in the terminally ill patient. ACP-ASIM End-of-Life Care Consensus Panel. American College of Physicians - American Society of Internal Medicine. Ann Intern Med2000;132(3):209–18. [published Online First: 2000/01/29].

Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, et al. Depression, hopelessness, and desire for hastened death in terminally ill patients with cancer. JAMA2000;284(22):2907–11. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.284.22.2907

Chochinov HM, Wilson KG, Enns M, et al. Depression, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation in the terminally ill. Psychosomatics. 1998;39(4):366–70.

Covinsky KE, Newcomer R, Fox P, et al. Patient and caregiver characteristics associated with depression in caregivers of patients with dementia. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(12):1006–14.

Hughes P, Kerr I. Transference and countertransference in communication between doctor and patient. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2000;6(1):57–64.

Irwin SA, Rao S, Bower K, et al. Psychiatric issues in palliative care: recognition of depression in patients enrolled in hospice care. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(2):158–63.

Lloyd-Williams M, Friedman T, Rudd N. A survey of antidepressant prescribing in the terminally ill. Palliat Med. 1999;13(3):243–8.

Lawrie I, Lloyd-Williams M, Taylor F. How do palliative medicine physicians assess and manage depression. Palliat Med. 2004;18(3):234–8.

Porche K, Reymond L, Callaghan JO, et al. Depression in palliative care patients: a survey of assessment and treatment practices of Australian and New Zealand palliative care specialists. Aust Health Rev. 2014;38(1):44–50.

Olajide O, Hanson L, Usher BM, et al. Validation of the palliative performance scale in the acute tertiary care hospital setting. J Palliat Med. 2007;10(1):111–7.

Glare P, Sinclair C, Downing M, et al. Predicting survival in patients with advanced disease. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(8):1146–56.

Aktas A, Walsh D, Rybicki L. Symptom clusters and prognosis in advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(11):2837–43.

Hosie A, Davidson PM, Agar M, et al. Delirium prevalence, incidence, and implications for screening in specialist palliative care inpatient settings: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2013;27(6):486–98.

Rayner L, Price A, Evans A, et al. Antidepressants for the treatment of depression in palliative care: systematic review and meta-analysis. Palliat Med. 2011;25(1):36–51.

Ng F, Crawford GB, Chur-Hansen A. Treatment approaches of palliative medicine specialists for depression in the palliative care setting: findings from a qualitative, in-depth interview study. BMJ Support Palliat Care2016;6(2):186–93. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000719 [published Online First: 2015/01/13].

Rayner L, Price A, Hotopf M, et al. Expert opinion on detecting and treating depression in palliative care: a Delphi study. BMC Palliat Care. 2011;10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-684X-10-10.

Rayner L, Higginson I, Price A, et al. The management of depression in palliative care: European clinical guidelines London: Department of Palliative Care, Policy & Rehabilitation, European Palliative Care Research Collaborative; 2010 [Available from: https://www.kcl.ac.uk/cicelysaunders/attachments/depression-guidlines/the-management-of-depression-in-palliative-care.pdf accessed 8th of May 2019.

Nelson JC, Papakostas GI. Atypical antipsychotic augmentation in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(9):980–91.

Ng CG, Boks MP, Roes KC, et al. Rapid response to methylphenidate as an add-on therapy to mirtazapine in the treatment of major depressive disorder in terminally ill cancer patients: a four-week, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol2014;24(4):491–98. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.01.016 [published Online First: 2014/02/08].

Loo C, Gálvez V, O'keefe E, et al. Placebo-controlled pilot trial testing dose titration and intravenous, intramuscular and subcutaneous routes for ketamine in depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;134(1):48–56.

Mulder ME, Verwey B, van Waarde JA. Electroconvulsive Therapy in a Terminally Ill Patient: When Every Day of Improvement Counts. The Journal of ECT2012;28(1):52–53. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/YCT.0b013e3182321181

IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 26.0) Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.; 2019 [Available from: https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/downloading-ibm-spss-statistics-26 accessed 20th of Sep 2020.

Morgan DL. Qualitative content analysis: a guide to paths not taken. Qual Health Res. 1993;3(1):112–21.

Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005, 15(9):1277–88.

QSR International. NVivo 12 1999 [Available from: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home accessed 30th of Apr 2021.

Lee W, Pulbrook M, Sheehan C, et al. Clinically Significant Depressive Symptoms are Prevalent in People with Extremely Short Prognoses-A Systematic Review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;61(1):143–66.e2.

Warmenhoven F, van Rijswijk E, van Hoogstraten E, et al. How family physicians address diagnosis and management of depression in palliative care patients. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(4):330–6. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1373.

Ng F, Crawford GB, Chur-Hansen A. How do palliative medicine specialists conceptualize depression? Findings from a qualitative in-depth interview study. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(3):318–24.

Murray J, Banerjee S, Byng R, et al. Primary care professionals’ perceptions of depression in older people: a qualitative study. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(5):1363–73.

Burroughs H, Lovell K, Morley M, et al. ‘Justifiable depression’: how primary care professionals and patients view late-life depression? A qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2006;23(3):369–77.

Endicott J. Measurement of depression in patients with cancer. Cancer. 1984, 53(10 Suppl):2243–9.

Furukawa TA, Streiner D, Young LT, et al. Antidepressants plus benzodiazepines for major depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;3.

Rasmussen KG, Richardson JW. Electroconvulsive therapy in palliative care. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine®2011;28(5):375–77.

Mellor D, McCabe MP, Davison TE, et al. Barriers to the detection and Management of Depression by palliative care professional Carers among their patients: perspectives from professional Carers and Patients' family members. Am J Hospice Palliat Med. 2013;30(1):12–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909112438705.

Meier DE, Beresford L. Growing the interface between palliative medicine and psychiatry. J Palliat Med 2010;13(7):803–806.

Patterson KR, Croom AR, Teverovsky EG, et al. Current State of Psychiatric Involvement on Palliative Care Consult Services: Results of a National Survey. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47(6):1019–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.06.015.

Fairman N, Irwin SA. Palliative care psychiatry: update on an emerging dimension of psychiatric practice. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2013;15(7):374–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-013-0374-3.

Sansom-Daly UM, Lobb EA, Evans HE, et al. To be mortal is human: professional consensus around the need for more psychology in palliative care. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care2021:bmjspcare-2021-002884. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2021-002884

Draper B, Brodaty H, Low LF. A tiered model of psychogeriatric service delivery: an evidence-based approach. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: A journal of the psychiatry of late life and allied sciences. 2006;21(7):645–53.

Lee W, Sheehan C, Chye R, et al. Study protocol for SKIPMDD: subcutaneous ketamine infusion in palliative care patients with advanced life limiting illnesses for major depressive disorder (phase II pilot feasibility study). BMJ open2021;11(6):e052312.

Grande G, Todd C. Why are trials in palliative care so difficult? Palliat Med2000;14(1):69–74.

Lee W, Pulbrook M, Sheehan C, et al. Evidence of Effective Interventions for Clinically Significant Depressive Symptoms in Individuals with Extremely Short Prognoses is Lacking – a Systematic Review. J Palliat Med 2021;(In Press).

O'Malley K, Blakley L, Ramos K, et al. Mental healthcare and palliative care: barriers. BMJ Support Palliat Care2021;11(2):138–44. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2019-001986 [published Online First: 2020/01/15].

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Clinical Prof Richard Chye, Sacred Heart Supportive & Palliative Care, St Vincent’s Hospital, Darlinghurst, NSW, Australia and University of Notre Dame, Australia for his support of this project.

Funding

The survey was funded by the Translational Cancer Research Network Clinical PhD Scholarship Top-up award, supported by the Cancer Institute New South Wales, Australia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Under the supervision of DC, MA, and BD, WL designed the survey and collected the data. WL analysed the data with statistical support of SC and qualitative analysis support of MD. WL drafted the manuscript and DC, MA, BD, MD and SC provided critical revisions throughout. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This project has been approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University Technology Sydney (approval number: ETH19-4071). Implied written informed consents have been obtained from all participants by participants proceeding with the online anonymous survey after accessing the participant information cover sheet. All procedures were performed in accordance with the principles set by the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare(s) that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Current palliative care physicians’ and psychiatrists’ practices, challenges and potential improvement strategies in assessing and managing depression in palliative patients with very poor prognoses.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, W., Chang, S., DiGiacomo, M. et al. Caring for depression in the dying is complex and challenging – survey of palliative physicians. BMC Palliat Care 21, 11 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-022-00901-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-022-00901-y