Abstract

Background

patients with palliative needs often experience high symptom burden which causes suffering to themselves and their families. Depression and psychological distress should not be considered a “normal event” in advanced disease patients and should be screened, diagnosed, acted on and followed-up. Psychological distress has been associated with greater physical symptom severity, suffering, and mortality in cancer patients. A holistic, but short measure should be used for physical and non-physical needs assessment. The Integrated Palliative care Outcome Scale is one such measure. This work aims to determine palliative needs of patients and explore screening accuracy of two items pertaining to psychological needs.

Methods

multi-centred observational study using convenience sampling. Data were collected in 9 Portuguese centres. Inclusion criteria: ≥18 years, mentally fit to give consent, diagnosed with an incurable, potentially life-threatening illness. Exclusion criteria: patient in distress (“unable to converse for a period of time”), cognitively impaired. Descriptive statistics used for demographics. Receiving Operator Characteristics curves and Area Under the Curve for anxiety and depression discriminant properties against the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

Results

1703 individuals were screened between July 1st, 2015 and February 2016. A total of 135 (7.9%) were included. Main reason for exclusion was being healthy (75.2%). The primary care centre screened most individuals, as they have the highest rates of daily patients and the majority are healthy. Mean age is 66.8 years (SD 12.7), 58 (43%) are female. Most patients had a cancer diagnosis 109 (80.7%). Items scoring highest (=4) were: family or friends anxious or worried (36.3%); feeling anxious or worried about illness (13.3%); feeling depressed (9.6%). Using a cut-off score of 2/3, Area Under the Curve for depression and anxiety items were above 70%.

Conclusions

main palliative needs were psychological, family related and spiritual. This suggests that clinical teams may better manage physical issues and there is room for improvement regarding non-physical needs. Using the Integrated Palliative care Outcome Scale systematically could aid clinical teams screening patients for distressing needs and track their progress in assisting patients and families with those issues.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Palliative care is a holistic approach of care, which can be integrated early in the disease trajectory, alongside active, curative treatment, [1] and aims to alleviate physical and non-physical symptoms of patients and their families [2,3,4,5,6,7]. Though physical symptoms may be more easily identified by healthcare professionals, patients and carers, non-physical symptoms can equally disrupt the patient and family’s quality of life and cause suffering [8]. Regarding effectiveness of psychological interventions to improve quality of life in people with long term conditions, results from a rapid systematic review show that there was a significant improvement in at least one quality of life outcome post-intervention and maintained at follow-up [9]. In another study, Ann-Yi S and colleagues report that 24% of palliative care in-patients and 19% of palliative care outpatients in a major cancer centre benefited from psychology services [8]. Also, psychological distress has been associated with greater physical symptom severity, suffering, and mortality in cancer patients [10]. Thus, these symptoms and needs should be properly assessed with validated outcome measures, and, the intervention(s) to solve or manage them should be selected accordingly [11, 12]. Depression and psychological distress are two examples of such needs, which should not be considered a “normal event” in an advanced disease trajectory [13]. Rather, they should be screened, diagnosed, acted on and followed-up by appropriate support services and specialised healthcare professionals, whether by pharmacologic treatment, psychological treatment, psychiatric treatment or a combination of those [13]. Patient centred outcome measures should be the first choice to measure subjective symptoms and needs, given that the patient is the best person to assess how the symptoms bother them. If the patient is cognitively impaired, a proxy version of the measure of choice can be used [14,15,16,17,18]. These measures are short, but multidimensional and some items may be used to screen for certain palliative needs, common in this population [19].

The aim of this study is to determine the main palliative care needs of patients being treated in portuguese health care services and to explore screening properties of two items pertaining to psychological needs, using the Integrated Palliative care Outcome Scale (IPOS) [20, 21]. We hypothesized that 1) anxiety and depression items will score highest among the non physical symptoms and 2) the area under the curve (AUC) to be > 0.7 for Items 3 (anxiety) and 5 (depression) in relation to the Portuguese Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [22] Anxiety subscale score and the HADS-Depression subscale total scores, respectively.

Methods

Patients and settings

This was a multi-centred observational study. Data were collected in nine portuguese centres spread out from north to south and rural to urban locations to maximise generalizability using convenience sampling. There were seven hospital based palliative care services, one oncology service and one primary care facility (health centre). All patients attending the participant services were screened for eligibility by the participating healthcare professionals. Inclusion criteria were as follows: ≥18 years, mentally fit to give consent judged as such by the participating healthcare professional, diagnosed with an incurable, potentially life-threatening illness, read, write and understand Portuguese. Exclusion criteria were: patient in distress (unable to maintain a conversation during a period of time) with uncontrolled physical or emotional symptoms, and/or cognitively impaired, judged as such by the participating healthcare professional. A standard operating procedures manual was developed and distributed to all centres in the person of the facilitator/champion leading the study locally. The detailed protocol has been published elsewhere [18].

Measures

The Portuguese version of the IPOS reported by the patient, previously developed, was used. The original measure has been culturally adapted and validated to European Portuguese [20, 21]. The protocol of the latter study has been published elsewhere [18] which contains the full questionnaire in the appendix. Next, we present a summary of main procedures and results. Two native Portuguese speaking translators, one clinical and one non-clinical independently created two Portuguese versions. A consensus Portuguese version was developed by two native Portuguese speaking independent reviewers blind to the original IPOS. This consensus version was sent to two other independent native Portuguese speaking translators, also blind to the original English IPOS, who back translated it into English. A second Portuguese consensus version was developed by the same reviewers. Three clinical revisions were performed by one specialist palliative care doctor, one specialist palliative care nurse and one non-clinical researcher – all native Portuguese. A final Portuguese version was created. There were grammatical and content differences in the first translation stage, in the items/questions text as well as in the response categories. These were resolved by discussion by both reviewers. There were also differences in the backward translation, namely verb tenses and the use of synonyms rather than the direct translation of words. These were resolved by discussion by the same reviewers. The clinical revisions flagged differences in verb tenses in three items. Those were discussed, and changes were made to create the final version. A Portuguese version of the IPOS was developed. Next, psychometric characteristics were assessed, namely, Internal consistency (excluding open questions, which are free text data) Cronbach’s alpha varied between 0.68 and 0.72, reliability between patients and healthcare professionals scores was assessed by intraclass correlation which was higher for mobility (ICC = 0.726 and lowest for practical problems (ICC = 0.088). Regarding construct validity, Items with similar constructs showed convergent validity and items with different constructs showed divergent validity. Spearman’s Rho varied between .390 and .631 with p ≤ .000. The measure also displayed good sensitivity to change, as Wilcoxon ranked test showed significant statistically differences between T1 and T2 in three symptoms. IPOS It is a brief, 19-item, multidimensional scale that captures core concerns in palliative care. The first item is an open question on the three main problems or worries the respondent might have had in the past week (results of this item are not reported in the present study given that data are free text); items 2 to 9 are set on a 5 point Likert scale based on descriptors (zero – not at all, 1 – slightly, 2 – moderately, 3 – severely, 4 – overwhelmingly), item two is a list of 10 of the most common physical symptoms in a palliative population, with the possibility of adding up to three more symptoms which are not present in the list; item 3 pertains to anxiety, item 4 asks about family/friends worry, item 5 is on depression; item 6 is about being at peace; item 7 relates to sharing feelings with significant people; item 8 is about information needs and item 9 concerns practical problems related to their illness. In the patient version (as opposed to the healthcare professional version), the questionnaire has an extra item asking if the respondent filled the questionnaire alone or with help. At the very end, there is a footnote to trigger the patient to talk to their healthcare professional, if they feel they are worried about any of the issues raised by the items in the questionnaire. This feature allows for real time clinical utility of the measure.

The Portuguese Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) is a 14 item screening measure for anxiety and depression states. The two subscales are comprised of 7 items each, scored separately, with descriptive answers based in a 4 point Likert scale. The authors propose a cut-off threshold of 11 for depression and anxiety. The authors conclude that the Portuguese HADS is a reliable and valid measure for assessing anxiety and depression in different medical settings and disease populations [22].

Analysis

After checking data quality and performing Little’s Missing Completely At Random (MCAR) test to check if data were missing at random, descriptive statistics were used to examine the distribution of demographic and clinical variables of interest. To determine accuracy of the items under study, we previously tested all possible cut-offs (results not presented) and decided to use the most appropriate, a cut-off score of 2/3. Then we compared all 5 psychological, emotional and spiritual needs items (IPOS items 3 to 7) against the Portuguese HADS. Receiver operating characteristic curves (ROC) were used to determine the 2 items displaying the highest AUC and assess discriminant properties, namely, sensitivity and specificity of the cut-off 2/3 for both items against cut-off 10/11 of the HADS Anxiety subscale and the HADS Depression subscale respectively. Positive (PPV) and negative predictive values (NPV), false negative (FNR) and false positive rates (FPR) and positive and negative likelihood ratios weighted by prevalence were also computed for both items. For sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV we considered 70% or above values to be acceptable and 80% or above to be high. For FPR and FNR of 30% or less, we considered them to be low. 95% confidence intervals were used. No sample size calculation was performed given that the only study found in the literature used the Palliative care Outcome Scale questionnaire (not the IPOS) and the HADS to screen for depression and anxiety was a secondary analysis of several independent datasets.

Ethics procedures

Ethical approval was granted from all relevant Research Ethics Committees and was in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical Standard. All participants gave informed signed consent. SPSS, version 22 (SPSS/IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) software was used.

Results

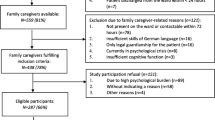

A total of 1703 individuals were screened between July 1st, 2015 and February 2016, the majority of which in a health centre, a primary health care facility. There were 18 (1.1%) patients eligible for the study who declined participation and 140 (8.2%) were excluded. A total of 135 (7.9%) patients were included (See Table 1).

Main reason for exclusion was being healthy (75.2%). This is expected given that the primary care centre screened most individuals, as they have the highest rates of daily patients and most of them are healthy. Mean age is 66.8 years (SD 12.7), 58 (43%) are female, 74 (54.8%) have up to 4 years of formal education, 74 (54.8%) are from the Northern region. Most patients (N = 109, 80.7%) had a cancer diagnosis and came from the 7 hospital palliative care services (See Table 2).

The main reasons for ineligibility and exclusion from the study are presented in Table 3. Most patients were approached to participate in the study whilst in external consultation, 98 (72.6%). About 31.1% were able to fill the questionnaires without help.

Data were missing at random (Little’s MCAR test showed Chi-Square = 2452.946, DF = 2398, Sig. = .213). Missing data varied between 1 and 5% (rates < 1% are trivial, 1–5% are manageable, 5–15% require sophisticated statistical methods to handle, and > 15% may severely impact any form of interpretation.) [23]. As expected in palliative populations, most questionnaire items presented a non-parametric distribution, so the imputation of the median was used to handle missing data.

Prevalence of needs

In terms of prevalence of needs, IPOS items scoring the highest (=4) were: family or friends anxious or worried (36.3%); feeling anxious or worried about illness (13.3%); feeling depressed (9.6%); feeling at peace (9.6%); share feelings (8.9%) and pain (7.4%). IPOS items scoring the lowest (=0) were: vomiting (77%); shortness of breath (67.4%); nausea (65%); information needs (60.7); practical problems (45.2%) and constipation (43%). (See Fig. 1).

Screening for anxiety and depression

Item 3 (anxiety) and item 5 (depression) presented the highest AUCs (see Fig. 2). The prevalence of depression was 24.4% (C.I. 17.6–32.7%). The AUC curve was 0.72 (C.I.:0.62–0.81), p < 0.001 (see Fig. 3). Sensitivity was 51.5% and specificity was 78.4%. Positive predictive value was 43.6% and negative predictive value was 83.3%. As for the anxiety item, the prevalence was 23.7% (C.I. 16.9%–.31.9%) and the AUC was 0.70 (C.I.:0.60–0.80), p < 0.001 (see Fig. 4). Sensitivity was 65.6% and specificity was 68.0%. Positive predictive value was 38.8% and negative predictive value was 86.4% (see Table 4).

Discussion

The main palliative needs of patients cared for by palliative care teams were psychological, family related and spiritual. IPOS systematically identified main needs in this population. Clinical teams seemed to solve or manage physical issues well. This is an extremely positive find. There is evidence that once physical needs are well managed, and the patient is more comfortable, non-physical palliative needs arise [24, 25]. These are also possible to and should be captured systematically in clinical practice, using a patient centred outcome measure and acted upon. In our study, the most stressful non physical issue was family or friends anxious or worried (36.3%). Given that Portuguese culture is based on strong family ties and that decisions are usually made within the family core, this was not surprising. Feeling anxious and depressed were the second and third most stressful issues, even though one of the exclusion criteria to be approached for invitation to participate in the study was being clearly in distress (physical or emotional) judged by direct observation of the healthcare professional. This reinforces the evidence that anxiety is often present in patients with advanced disease due to uncertainties in diagnostic, treatment and prognostic, [13] and, depression is also common among patients with advanced disease [26]. In our sample the prevalence of these issues resonates with Ann-Yi S study in terms of the percentage of patients cared for in the psychology service [8], although that study was conducted only with cancer patients. On the other hand, clusters of physical and non physical symptoms occur and are common in both cancer and non cancer patients [27, 28]. Also, the prevalence of depression in the present study was somewhat higher than the one presented in the Antunes study on screening for depression using one item of the Palliative care Outcome Scale, namely 17.5% (C.I. 14.1–21.6%) [20], but lower than the 30% estimated by Hotopf and colleagues for prevalence of all depressive disorders in advanced disease [29].

Both AUC for anxiety and depression were acceptable (70% or above), although both C.I.s lower levels were slightly below 70%. For cut-off 2/3, both items did not perform well regarding sensitivity, which means these might not be good to identify true positive cases. However, specificity and NPV were good. Both items seem to be good excluding true negative cases, which is one component of screening [30]. These results also reinforce external validity of IPOS.

The main limitation in our study is that the optimal gold standard to screen for anxiety and depression - psychiatric interview for depression as determined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition) was not available to use due to low resources available. The present study used the HADS, a screening measure well accepted in practice and that has been used extensively both in practice and research for several years, nevertheless this is not a diagnostic tool.

Using IPOS systematically could aid clinical teams to track their progress in assisting patients and families with physical and non-physical symptoms. Like other screening tools the Portuguese Integrated Palliative care Outcome Scale seems to be good for excluding true negative cases of depression (item 5) and anxiety (item 3) and can be used to screen patients with advanced disease [30, 31].

Conclusions

Patient centred outcome measures are powerful communication tools, allowing all those involved in patient care to use a common language, serving not only patients and families, but aiding healthcare professionals, health institutions and policy makers to make evidence supported decisions and improve patient centred care. Building evidence of screening properties of these measures allows not only for patient clinical care, but also to conduct more robust research studies. This study determined screening accuracy properties of the Portuguese Integrated Palliative care Outcome Scale for two psychological related items and shows that this measure can be used to screen patients with advanced disease.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- IPOS:

-

Integrated Palliative Outcome Scale

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- HADS:

-

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic curve

- PPV:

-

Positive predictive value

- NPV:

-

Negative predictive value

- FNR:

-

False negative rate

- FPR:

-

False positive rate

- CI:

-

Confidence intervals

References

Oliver D. Improving patient outcomes through palliative care integration in other specialised health services: what we have learned so far and how can we improve? Ann Palliat Med. 2018. https://doi.org/10.21037/apm.2018.05.05.

Clark D. Between hope and acceptance: the medicalisation of dying. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2002;324:905–7.

Bajwah S, Higginson IJ. Ross, Wells AU, birring SS, Patel a et al. specialist palliative care is more than drugs: a retrospective study of ILD patients. Lung. 2012;190:215–20.

Jocham HR, Dassen T, Widdershoven G, Halfens R. Quality of life in palliative care cancer patients: a literature review. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15:1188–95.

Stewart AL, Teno J, Patrick DL, Lynn J. The concept of quality of life of dying persons in the context of health care. J Pain Symptom Manag. 1999;17:93–108.

Kupfer JM, Bond EU. Patient satisfaction and patient-centered care: necessary but not equal. JAMA. 2012;308:139–40.

"WHO Definition of Palliative Care". World Health Organization. Retrieved July 10, 2018. http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/.

Ann-Yi S, Bruera E, Wu J, Liu DD, Agosta M, Williams JL, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of psychology referrals in palliative care department. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.05.022.

Anderson N, Ozakinci G. Effectiveness of psychological interventions to improve quality of life in people with long-term conditions: rapid systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMC Psychology. 2018;6:11.

Hamer M, Chida Y, Molloy GJ. Psychological distress and cancer mortality. J Psychosom res 2009;66:255-8. Krikorian a, Limonero JT, Roman JP, Vargas JJ, Palacio C. predictors of suffering in advanced cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2014;31:534–42.

Bausewein C, Daveson BA, Currow DC, Downing J, Deliens L, Radbruch L, et al. EAPC white paper on outcome measurement in palliative care: improving practice, attaining outcomes and delivering quality services – recommendations from the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) task force on outcome measurement. Palliat Med. 2016;30(1):6–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216315589898 Epub 2015 Jun 11.

Bausewein C, Daveson B, Benalia H, Simon ST, Higginson IJ. Outcome measurement in palliative care. London: PRISMA; 2011. http://pos-pal.org/Resources.php.

Götze H, Brähler E, Gansera L, Polze N, Köhler N. Psychological distress and quality of life of palliative cancer patients and their caring relatives during home care. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:2775–82.

User’s Guide for Implementing Patient-Reported Outcomes Assessment in Clinical Practice. http://www.isoqol.org/UserFiles/file/UsersGuide.pdf visited on the 27th July 2014.

Antunes B, Harding R, Higginson IJ, on behalf of EUROIMPACT. Implementing patient-reported outcome measures in palliative care clinical practice: a systematic review of facilitators and barriers. Palliat Med. 2014;28:158–75.

Etkind SN, Daveson BA, Kwok W, Witt J, Bausewein C, Higginson IJ, et al. Capture, transfer, and feedback of patient centred outcomes data in palliative care populations: does it make a difference? A systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2015;49(3):611–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.07.010 Epub 2014 Aug 15.

Murtagh F, Ramsenthaler C, Firth A, Groeneveld EI, Lovell N, Simon S et al. A Brief, Patient- and Proxy-reported Outcome Measure for the Adult Palliative Care Population: Validity and Reliability of the Integrated Palliative Outcome Scale (IPOS) 9th World Research Congress of the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC); 2016.

Antunes B, Ferreira PL. Integrated palliative care outcome scale: Protocol Validation for the Portuguese population. Revista Cuidados Paliativos. 2017;4-N 1-julho 2017 http://www.apcp.com.pt/revista-cuidados-paliativos/revista-cuidados-paliativos-volume-4-n.-1-julho-2017.html.

Antunes B, Murtagh F, Bausewein C, Harding R, Higginson IJ. Screening for depression in advanced disease: psychometric properties, sensitivity and specificity of two items of the palliative care outcome scale (POS). J Pain Symptom Manag. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.06.014.

Antunes B, Rodrigues PP, Higginson IJ, Ferreira PL. “Validation and cultural adaptation of the integrated palliative care outcome scale (IPOS) for the Portuguese population” poster at 5th world congress of the European Association for Palliative Care in Madrid, Spain on 18–20; 2017.

Antunes B, Rodrigues PP, Higginson IJ, Ferreira PL. "Validation of the integrated palliative care outcome scale (IPOS) to the Portuguese population - completion assessment and thematic analysis of the open question items" oral presentation at the 5th world congress of the European Association for Palliative Care in Madrid, Spain on 18–20 2017.

Pais-Ribeiro J, Silva I, Ferreira T, Martins A, Meneses R, Baltar M. Validation study of a Portuguese version of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. Psychol Health Med. 2007;12(2):225–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548500500524088.

Acuñna E, Rodriguez C. The treatment of missing values and its effect on classifier accuracy. In: Banks D, House L, FR MM, Arabie P, Gaul W, editors. Classification, Clustering and Data Mining Applications. Berlin: Springer; 2004. p. 639e648.

Mistry B, Bainbridge D, Bryant D, Tan Toyofuku S, Seow H. What matters most for end-of-life care? Perspectives from community-based palliative care providers and administrators. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e007492. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007492.

Wang T, Molassiotis A, Chung BPM, Tan JY. Unmet care needs of advanced cancer patients and their informal caregivers: a systematic review. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17(1):96. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-018-0346-9.

Rayner L, Price A, Hotopf M, Higginson IJ. The development of evidence-based European guidelines on the management of depression in palliative cancer care. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:702e712.

Moens K, Higginson IJ, Harding R. EURO IMPACT. Are there differences in the prevalence of palliative care-related problems in people living with advanced cancer and eight non-cancer conditions? A systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2014;48:660–77.

Stiel S, Matthies DM, Seuss D, Walsh D, Lindena G, Ostgathe C. Symptoms and problem clusters in cancer and non-cancer patients in specialized palliative care—is there a difference? J Pain Symptom Manag. 2014;48:26–35.

Hotopf M, Chidgey J, Addington-Hall J, Ly KL. Depression in advanced disease: a systematic review. Part 1. Prevalence and case finding. Palliat Med. 2002;16:81e97.

Mitchell AJ. Are one or two simple questions sufficient to detect depression in cancer and palliative care? A Bayesian meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:1934–43. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6604396.

Payne A, Barry S, Creedon B, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of a two-question screening tool for depression in a specialist palliative care unit. Palliat Med. 2007;21:193e198.

Acknowledgments

To all patients who contributed for data collection our most profound appreciation. Without them this work would not have been possible. Thank you to all healthcare professionals and care teams who performed data collection: Equipa de Cuidados Paliativos do Hospital S. João de Deus de Montemor-o-Novo; Serviço de Oncologia do CHVNG/E, Dr. Moreira Pinto, Dr. Enrique Dias, Dra. Ana Joaquim, Dra. Teresa Sarmento, Dra. Sandra Custódio; Equipa Intra Hospitalar de Suporte em Cuidados Paliativos (EIHSCP) do CHVNGaia/Espinho, EPE; Unidade de Assistência Domiciliária do IPOLFG e Equipa Intra-hospitalar de Suporte em Cuidados Paliativos do IPOLFG, EPE; Serviço de Cuidados Paliativos do Centro Hospitalar de São João, E.P.E., Nurse Cátia Coelho; Departamento de Cuidados Paliativos Unidade Local de Saúde do Nordeste, Duarte Soares MD, Sara Fernandes Psychologist, Silvia Asseiro Social Carer; USF São Julião - Figueira da Foz, Sara Marques Baptista MD, Sandra Inês Diniz Amaral MD, Pedro Alexandre Santos Carvalho Figueiredo MD, Ana Raquel Melo Borges de Castro MD; Unidade de Saúde Familiar AlphaMouro and Unidade de Cuidados Paliativos do Centro Hospitalar Lisboa Norte, EPE.

This work has been presented in a poster format at an International conference in 2018: Antunes B, Rodrigues PP, Higginson IJ, Ferreira PL. “Screening for Depression in Advanced Disease Using One Item of the Portuguese Integrated Palliative Care Outcome Scale” 10th World Research Congress of the European Association for Palliative Care in Bern, Switzerland, May 24-26th 2018.

Funding

This study was funded by Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation – Programa Gulbenkian Inovar em Saúde.

Bárbara Antunes was funded by Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) - Grant number PD/BD/113664/2015, Faculty of Medicine, University of Porto.

The Doctoral Program Clinical and Health Services Research was funded by FCT - Grant number PD/0003/2013. Currently Bárbara Antunes is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration East of England (ARC EoE) programme. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. The funding organizations had no role in the design of the study, collection, analysis, interpretation of the data, or writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BA performed study procedures and collection of data, analysis of data, and was responsible for drafting and editing of the manuscript; PPR revised the manuscript; IJH revised the manuscript; PLF revised of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was granted from all Research Ethics Committees’ included centres and was in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical Standard: Comissão de Ética para a Saúde do Centro Hospitalar de S. João – Entidade Pública Empresarial (no reference number); Comissão de Ética para a Saúde Administração Regional de Saúde Centro - 77/2015; Comissão de Ética para a Saúde de Lisboa e Vale do Tejo – 6801/CES/2015; Comissão de Ética do Centro Hospitalar de Vila Nova de Gaia/Espinho – 275/2015; Conselho de Investigação e da Comissão de Ética do Instituto Português de Oncologia de Lisboa Francisco Gentil, Entidade Pública Empresarial – UIC/967 n° 89/2015; Comissão de Ética Instituto S. João de Deus – CEISJD03_15; Comissão de Ética do Centro Académico de Medicina de Lisboa – 51/15; Comissão de Ética da Unidade Local de Saúde do Nordeste Entidade Pública Empresarial – p°, CE.

Informed written (signed) consent was obtained from all participants (patients and healthcare professionals).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Antunes, B., Rodrigues, P.P., Higginson, I.J. et al. Determining the prevalence of palliative needs and exploring screening accuracy of depression and anxiety items of the integrated palliative care outcome scale – a multi-centre study. BMC Palliat Care 19, 69 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-020-00571-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-020-00571-8