Abstract

Background

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is one of the leading causes of pulpitis. The differences in establishing an in vitro pulpitis model by using different lipopolysaccharides (LPSs) are unknown. This study aimed to determine the discrepancy in the ability to induce the expression of inflammatory cytokines and the underlying mechanism between Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Porphyromonas gingivalis (P. gingivalis) LPSs in human dental pulp stem cells (hDPSCs).

Material and methods

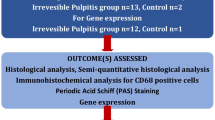

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (QRT-PCR) was used to evaluate the mRNA levels of inflammatory cytokines including IL-6, IL-8, COX-2, IL-1β, and TNF-α expressed by hDPSCs at each time point. ELISA was used to assess the interleukin-6 (IL-6) protein level. The role of toll-like receptors (TLR)2 and TLR4 in the inflammatory response in hDPSCs initiated by LPSs was assessed by QRT-PCR and flow cytometry.

Results

The E. coli LPS significantly enhanced the mRNA expression of inflammatory cytokines and the production of the IL-6 protein (p < 0.05) in hDPSCs. The peaks of all observed inflammation mediators’ expression in hDPSCs were reached 3–12 h after stimulation by 1 μg/mL E. coli LPS. E. coli LPS enhanced the TLR4 expression (p < 0.05) but not TLR2 in hDPSCs, whereas P. gingivalis LPS did not affect TLR2 or TLR4 expression in hDPSCs. The TLR4 inhibitor pretreatment significantly inhibited the gene expression of inflammatory cytokines upregulated by E. coli LPS (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

Under the condition of this study, E. coli LPS but not P. gingivalis LPS is effective in promoting the expression of inflammatory cytokines by hDPSCs. E. coli LPS increases the TLR4 expression in hDPSCs. P. gingivalis LPS has no effect on TLR2 or TLR4 expression in hDPSCs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pulpitis is an inflammatory pathosis of pulp tissue in response to various external stimuli primarily caused by bacterial infection. As a richly vascularized and innervated connective tissue, dental pulp is composed of diverse cell populations, among which dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) are pivotal for their highly proliferative potential, self-renewal capability, and multilineage differentiation aptitude [1], DPSCs continuously replenish odontoblasts to form secondary and tertiary dentin throughout adult life and in reaction to insults [2]. Upon stimulation of lipopolysaccharides (LPSs), DPSCs could be recruited from their niche, migrate to the site of inflammation, and differentiate into odontoblast-like cells to form reparative dentin. LPS has also been reported to be involved in mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) differentiation and inflammatory responses [3]. It has been reported that human dental pulp stem cells (hDPSCs) from carious teeth manifested enhanced proliferation and osteogenic differentiation in comparison with their counterparts from healthy teeth [4]. DPSCs is regarded as a readily available source of multipotent stromal cells for tissue regeneration. DPSCs also involved in modulation of pulp inflammation [5]. Recent evidences have revealed that DPSCs could modulate the secretion of inflammatory cytokines and participate in the host immune response [6,7,8]. The immunomodulatory potential of DPSCs may be of particular importance for pulp tissue to repair or regenerate under conditions of pulpitis. To date, many studies have focused on the role of DPSCs in the progression and treatment of pulpitis via establishing in vitro pulpitis models to simulate an inflammatory environment of DPSCs [7, 9, 10].

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are pattern recognition receptors sensing specific pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), connecting innate and adaptive immunity. TLRs are crucial in pathogenesis of chronic inflammatory, autoimmune, and infectious diseases [11]. So far, 10 functional human TLRs have been identified. Among them, TLR2 and TLR4 are extracellular TLRs which could recognize peptidoglycans and lipoteichoic acid (LTA) of Gram-positive bacteria [12, 13] and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) primarily from Gram-negative bacteria [14] respectively. When cultured in vitro, DPSCs express TLRs 1–10 at differential levels, with TLR2 and TLR4 in significant amounts, making them susceptible to LPS or LTA [15].

LPS, composed of lipids and polysaccharides, is a major component of the membrane of gram-negative bacteria that causes cell inflammation [16, 17]. By binding to TLRs of the cell, LPS activates various downstream signaling pathways, leading to the synthesis of inflammation mediators, such as interleukin (IL)-1β, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), IL-6, IL-8, and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) [18, 19]. Being the critical initiator in pulpitis pathogenesis, bacterial LPS penetrates into the affected dental pulp tissue, motivates substantial release of inflammatory mediators from dental pulp, such as IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-8 [20, 21], thus triggering the inflammatory response of the dental pulp [22, 23]. The inflammation-inducing effects of LPS varies among different bacterial sources and different target cells. Nebel et al. compared the IL-6 gene and protein production of human periodontal ligament cells (hPDLCs) upon stimulation by LPSs from Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Porphyromonas gingivalis (P. gingivalis) [24]. They found that E. coli LPS enhances the IL-6 expression dramatically, whereas P. gingivalis LPS has no effect on hPDLCs. In another study, gingival fibroblast cells are reported to be more sensitive to E. coli LPS than to P. gingivalis LPS in the expression of inducible nitric oxide, IL-6, and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) [25]. By contrast, macrophages manifest a more robust inflammatory reaction in expression of of IL-1β, IL-6, and MCP-1 in response to P. gingivalis LPS in comparison with E. coli LPS [25]. In a study conducted by Palaska et al., no significant difference in inflammatory response of human mast cells between P. gingivalis LPS and E. coli LPS was observed [26]. Obviously, the inflammation-inducing impact of LPS on target cells is both bacteria-specific and cell-specific.

Different stimuli such as LPS, TNF, bacterial extracts are used to imitate an inflammatory dental pulp microenvironment [27,28,29]. To stimulate DPSCs in establishing in vitro pulpitis models, many researchers use E. coli LPS [10, 30] whereas others use P. gingivalis LPS [27, 31]. LPS from E. coli, targets TLR4 and activates the downstream NF-κB signaling pathway, leading to the expression of inflammatory cytokines [32]. The interaction of P. gingivalis LPS with TLR2 or TLR4 remains controversial [33]. The TLR2 activity of P. gingivalis LPS might be caused by a contaminant lipoprotein [34]. As LPSs of different bacteria have been used in these studies, it is imperative to understand the discrepancy of the inflammation-inducing property between E. coli and P. gingivalis LPSs when interpretting and comparing these results. According to a most recently published systematic review [35], despite 105 in vitro studies using LPS in induction of pulp cell inflammation have been reported so far, only 2 experiments adopted both E. coli and P. gingivalis LPSs in stimulating heterogenous dental pulp cells [36, 37]. Moreover, scarce evidence exists comparing the inflammatory effects of E. coli and P. gingivalis LPS on DPSCs. Thus, our study aims to determine the differences in the ability to induce the expression of inflammatory cytokines over time by hDPSCs between E. coli and P. gingivalis LPSs. Furthermore, we have investigated the role of TLR4 and TLR2 in hDPSCs response to E. coli and P. gingivalis LPS-induced inflammation. The hypothesis is that the LPS from E. coli is more potent than the LPS from P. gingivalis in eliciting inflammatory reactions in hDPSCs. The LPSs could induce proinflammatory expression in hDPSCs via TLR4. The novelty of this study is to provide comparative data of the inflammation-inducing capacitity between E. coli and P. gingivalis LPSs on hDPSCs.

Materials & methods

Cell isolation and culture

We collected impacted molars without caries from healthy volunteers aged 18 to 25 years. The procedures of collecting the extracted teeth were under the Committee of Ethics of School and Hospital of Stomatology, Fujian Medical University (No.201652), and informed consent was obtained. Immediately after extraction, each tooth was fractured into several parts by pliers (bone forceps) under sterile conditions. The dental pulp tissue from the teeth was isolated and collected into the Eppendorf tube. As described in the previous study, the pulp tissue was minced into 1 × 1 mm2 fragments and digested with a mix of type I collagenase (3 mg/ml) and dispase (4 mg/ml; Sigma -Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) for 30–60 min at 37 °C [38]. Next, we obtained a single-cell suspension using a 70 mm cell strainer to filter solutions[38]. The suspension was then transferred onto a 6 cm culture dish, and cultured in an incubator maintained at 37 °C containing 5% carbon dioxide. The minimum essential medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco BRL, Rockville, MD, USA), 100 mg/ml streptomycin (Gibco BRL), and 100 units/ml penicillin (Gibco BRL) was used as culture medium. We used the third and fourth passage cells in subsequent experiments.

Characterization of hDPSCs

Following the method in a previous study [39], the mesenchymal antigen markers of the cells were identified using flow cytometry. The fluorescently conjugated antibodies used were as follows (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA): anti-CD90-allophycocyanin (APC), anti-CD105-phycoerythrin (PE), anti-CD73-PE, anti-CD146-PE, anti-CD45-APC, and anti-CD34-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC). Correspondingly conjugated isotype control included mouse IgG-APC, IgG-PE, and IgG-FITC.

The cells were cultured in an osteogenic induction medium supplemented with 10 nM dexamethasone, 0.2 mM ascorbic acid-2-phosphate, and 10 mM sodium β-glycerophosphate (Sigma-Aldrich) for osteogenic differentiation for 3 weeks. Then the culture was fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min and stained with 2% Alizarin Red.

The cells were cultured in the adipogenic induction medium (Cyagen, Santa Clara, CA, USA) for 3 weeks and then stained with oil red “O” solution (Sigma-Aldrich) to test the adipogenic differentiation ability.

The colony-forming unit (CFU) test was carried out to determine the self-renewal potential of the isolated cells. Briefly, 1000 cells per well were seeded in a 6-well dish and cultured in the growth medium. The culture medium was changed every 3 days. After 14 days, cells were stained with 0.5% crystal violet solution for 30 min, observed, and photographed using a microscope.

The immunofluorescence staining for specific proteins was performed to detect the origin of cells. The immunofluorescence staining protocol was in accordance with a previous study [40]. Rabbit antihuman vimentin (Abclonal, Woburn, MA, USA) and rabbit antihuman cytokeratin (Abclonal) proteins referred to mesenchymal and epithelial origins. FITC-labeled goat antirabbit IgG (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) was used as the secondary antibody, and DAPI (Solarbio, Beijing, China) was used as nuclear-staining fluorescence.

LPS treatment and grouping

Upon reaching 80%–90% confluence, hDPSCs were stimulated with LPS of P. gingivalis (InvivoGen, Carlsbad, CA, USA)(standard version, # tlrl-pglps) or E.coli (Sigma Aldrich) (serotype 055:B5, L5418) at the concentration of 1 μg/mL [41, 42] referring to a previous study [43]. The cells not treated by E. coli LPS or P. gingivalis LPS were used as the control group. The treated cells at different time points (1.5, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h) were harvested for assessing the mRNA expression of IL-6, IL-8, COX-2, IL-1β, and TNF-α. Besides, we measured the gene levels of TLR4 and TLR2 stimulated by E. coli and P. gingivalis LPSs (1 μg/mL) at 1.5, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h to investigate the underlying mechanism of LPS-induced inflammation of hDPSCs. Also, we explored the effects of E. coli and P. gingivalis LPSs (1 μg/mL) on the protein production of TLR4 and TLR2 in hDPSCs by flow cytometry. Furthermore, cells were pretreated with or without 10 μmol/L TAK-242 (HY-11109, MedChem Express, NJ, USA) for 30 min and added with E. coli LPS (1 μg/mL) for another 3 h to confirm how TLR4 acted in the inflammatory mediator expression of hDPSCs induced by E. coli LPS. Afterward, we collected all cells and evaluated the fluctuation in the gene expression levels of IL-6, IL-8, COX-2, IL-1β, TNF-α, and TLR4.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (QRT-PCR)

Briefly, we extracted the total RNA of hDPSCs by using Trizol (Invitrogen). According to the manufacturer’s protocol, we synthesized the cDNA from 1 μg total RNA using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit with the gDNA Eraser (Takara, Kusatsu, Japan). The primer sequences used in our research are shown in Additional file 1: Table S1. Each cDNA sample was amplified in triplicate on the LightCycler 480 II real-time PCR system using a two-step method. The expression of targeted genes was analyzed by calculating the amount of target cDNA relative to the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase following the 2−ΔΔCT principle.

Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

The IL-6 protein released into the cell culture supernatant was measured to assess the influence of E. coli and P. gingivalis LPSs on the inflammation-inducing ability. The hDPSCs were cultured in triplicate at a density of 5 × 104 per well in 24-well plates in the completed culture medium containing 10% FBS. After reaching approximately 80% confluence, the medium was removed and replaced with a new medium free of serum for 18 h. Then, hDPSCs were stimulated by 1 μg/mL E. coli LPS or 1 μg/mL P. gingivalis LPS in the completed medium for another 24 h. Supernatants were gathered and stored at 80 °C until further use. By the manufacturer's protocol, we analyzed the IL-6 protein level from culture supernatants using a commercially available human-specific ELISA kit (Neobioscience, Shenzhen, China).

Flow cytometry

The BD Accuri C6 Software was used to investigate TLR4 and TLR2 expression on the surface of hDPSCs stimulated by LPS (1 μg/mL) from E. coli or P. gingivalis. Cells were collected, washed with PBS, counted, and then resuspended in the staining buffer. Cells were incubated with the anti-TLR4 antibody (Abcam) (ab13556) or anti-TLR2 antibody (Abcam) (ab213676) for 1 h at 4 °C. The secondary antibody diluted to 1/2000 was added for another 30 min in the dark (Abcam) (ab150079). The isotype control antibody (Abcam) (ab37415) was used under the same conditions. Data analysis was performed using the FlowJo 10.6.2 software.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as a mean ± standard deviation and analyzed using one-way Analysis of variance, followed by Tukey’s test (equal variance) or Dunnett’s T3 (unequal variance). Statistical significance was determined at p < 0.05.

Results

Characterization results of hDPSCs

The flow cytometry showed mesenchymal markers (CD73, CD105, CD90, CD146) positive and hematopoietic markers (CD34, CD45) negative on hDPSCs (Fig. 1A). Many mineralized nodules and several red lipid droplets formed in hDPSCs, respectively (Fig. 1B, C). The CFU test showed prominent colonies in hDPSCs, displaying the apparent self-proliferation capacity of hDPSCs (Fig. 1D, d). The isolated cells were positive for anti-vimentin and negative for anti-cytokeratin, proving that hDPSCs in our study were derived from human mesenchymal cells (Fig. 1E).

Characterization of hDPSCs. A Representative histograms about surface markers on hDPSCs by flow cytometry. B Mineralized nodules formed in hDPSCs after osteogenic differentiation for 3 weeks. C Lipid droplets after adipogenic induction in hDPSCs for 3 weeks. D, d Colonies of hDPSCs visualized using crystal violet staining. E Positive immunofluorescence to vimentin and negative immunofluorescence to cytokeratin of hDPSCs. All scale bars are equal to 50 μm in B–E

Inflammatory cytokine mRNA expression

Compared with the untreated cell, hDPSCs stimulated by E. coli LPS (1 μg/mL) significantly upregulated IL-6 mRNA expression at all observed time points (p < 0.05, Fig. 2A). The IL-8 mRNA level was increased significantly in hDPSCs stimulated by E. coli LPS from 1.5 h to 24 h (p < 0.05, Fig. 2B). The gene expression levels of COX-2 and IL-1β by hDPSCs were significantly increased from 3 to 12 h in the group stimulated by E. coli LPS (p < 0.05, Fig. 2C, D). E. coli LPS elicited a significant upregulation of TNF-α mRNA in hDPSCs at 1.5 and 3 h (p < 0.05, Fig. 2E). However, we detected no IL-6, IL-8, COX-2, IL-1β and TNF-α expression level discrepancy in hDPSCs between the P. gingivalis LPS and the control groups at each time point (p > 0.05, Fig. 2A–E). In our study, a high concentration of P. gingivalis LPS (10 μg/mL) showed no elevated mRNA expression level of proinflammatory cytokines in hDPSCs (Additional file 2: Fig. S1).

Inflammatory cytokines mRNA expression patterns in hDPSCs triggered by E. coli or P. gingivalis LPS. A IL-6, B IL-8, C COX-2 D IL-1β, and E TNF-α mRNA. Cells are stimulated by 1 μg/mL LPS from E. coli or P. gingivalis for 0.75,1.5, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h, respectively. The cells without LPS treatment (untreated cells) were used as the control group. This figure is a typical one of three independent experiments with three replications for each experiment. Data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3). Y-axis represents the relative fold expression of inflammatory mediators relative to the control group. *p < 0.05, vs the control group at the same time point

In general, only the LPS from E. coli notably improved IL-8, IL-6, COX-2, IL-1β, TNF-α mRNA expression levels in hDPSCs, and the peaks expression levels of above inflammatory cytokines were reached at 3 h –12 h (Fig. 2).

IL-6 protein expression

Results showed that the IL-6 protein production was significantly enhanced by E. coli LPS stimulation (p < 0.05). However, the protein production of IL-6 remained low in the 1 μg/mL P. gingivalis LPS stimulation group, and this finding was similar to that in the control group (p > 0.05, Fig. 3).

IL-6 protein concentration from the cell supernatant of hDPSCs through ELISA. The same concentration of LPS (1 μg/mL) from E. coli- or P. gingivalis-treated hDPSCs for 24 h. Data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3). Cells without E. coli or P. gingivalis LPS treatment serve as the control group. ***p < 0.001

TLR4 and TLR2 expression reactions to E. coli or P. gingivalis LPS

The TLR4 and TLR2 mRNA expression levels by hDPSCs were measured using QRT-PCR. Results showed that 1 μg/ mL E. coli LPS significantly increased the TLR4 gene expression at 3 h (p < 0.001, Fig. 4B), 6 h (p < 0.05, Fig. 4C), 12 h (p < 0.05, Fig. 4D), and 24 h (p < 0.01, Fig. 4E), respectively. Moreover, the relative expression fold of TLR4 mRNA in the E. coli LPS group was highest at 3 h compared with that in the control group, corresponding to the peak expression period of proinflammatory cytokines. Nevertheless, no significant change in the mRNA expression was observed in hDPSCs activated by 1 μg/ mL P. gingivalis LPS (p > 0.05, Fig. 4). The expression of TLR2 mRNA was altered by neither E. coli nor P. gingivalis LPS in hDPSCs (p > 0.05, Fig. 4). Then, the flow cytometry analysis further verified the results of QRT-PCR (Fig. 5). The TLR4 production increased on the surface of hDPSCs initiated by 1 μg/ mL E. coli LPS (Fig. 5A, C). In contrast, the TLR4 protein amount in the 1 μg/ mL P. gingivalis LPS group was similar to that in the control group (Fig. 5A, B). However, the TLR2 protein was maintained at a deficient level on the surface of hDPSCs stimulated by 1 μg/ mL LPS from E. coli or P. gingivalis (Fig. 5D–F).

TLR4 and TLR2 mRNA expression in hDPSCs elicited by E. coli or P. gingivalis LPS. Cells are motivated by E. coli or P. gingivalis LPS (1 μg/mL). Cells without LPS stimulus serve as the control group. TLR4 and TLR2 on mRNA levels at A 1.5 h, B 3 h. C 6 h, D 12 h, and E 24 h. Data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Production of TLR4 and TLR2 proteins on the surface of hDPSCs by flow cytometry. Cells are stimulated with E. coli or P. gingivalis LPS (1 μg/mL) for 24 h. Cells without LPS stimulus serve as the control group. Expression levels of A–C TLR4 and D–F TLR2 on the cell surface. Red-filled or unfilled histograms refer to TLR4 and TLR2, respectively, whereas blue-filled or unfilled histograms refer to the Isotype control IgG

TLR4 involved in the upregulation of inflammatory cytokines in hDPSCs by E. coli LPS

The TLR4 selective inhibitor TAK-242 was applied to confirm whether TLR4 participated in the expression of proinflammatory cytokines incited by 1 μg/ mL E. coli LPS in hDPSCs. First, our results revealed that 10 μmol/L TAK-242 could significantly block the expression of TLR4 in the group treated with E. coli LPS (p < 0.05) but did not influence the expression of TLR2 (p > 0.05, Fig. 6). As shown in Fig. 7, the pretreatment of TAK-242 significantly inhibited the E. coli LPS-induced expression of proinflammatory cytokines in hDPSCs, including IL-8, IL-6, COX-2, IL-1β, and TNF-α (p < 0.05).

TAK-242 on E. coli LPS-induced TLR4 and TLR2 mRNA expression in hDPSCs. Treatment groups are added with TAK-242 in advance for 30 min and exposed to 1 μg/mL E. coli LPS for another 3 h. Cells without LPS stimulus and TAK-242 serve as the control group. Lines above the bar connect the two groups with statistical differences marked with star symbols. Data used are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

TAK-242 on the mRNA expression of E. coli LPS-induced inflammatory cytokines in hDPSCs. The hDPSCs are pretreated with or without TAK-242 for 30 min and exposed to 1 μg/mL E. coli LPS for another 3 h. Cells without LPS stimulus and TAK-242 serve as the control group. Lines above the bar connect the two groups with statistical differences marked with star symbols. Data used are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Discussion

Our research displays different inflammatory cytokine patterns in hDPSCs induced by E. coli LPS and P. gingivalis LPS. Only the LPS from E. coli significantly increases the expression of proinflammatory cytokines in hDPSCs within 24 h. Consistently, E. coli LPS increases the TLR4 expression in hDPSCs. Our results suggested that E. coli LPS but not P. gingivalis LPS should be used to stimulate hDPSCs in establishing an in vitro model of pulpitis.

The expression levels of inflammatory cytokines can reflect the pathological state in dental pulp tissue [44]. IL-1β is one of the essential mediators of acute dental pulp inflammation, and the increase of IL-1β level in dental pulp tissue aggravates the pulp inflammation [45]. IL-6 is a classic type of proinflammatory cytokine that mediates pulp inflammation [46]. IL-6 production in inflamed dental pulp tissues is significantly higher than in healthy tissues [47]. TNF-α, as an indicator of early pulp inflammation, plays a vital role in the pulp immune response [48]. IL-8 shows rapid chemotaxis and recruits immune cells to the inflammatory site [49], and COX-2 can induce vascular endothelial growth factor, thus promoting pulp inflammation [50].

The time-dependent expression pattern of cytokines in hDPSCs by LPSs is conducive to determining an optimal stimulation time to establish an in vitro model of pulpitis. Our research has compared the expression patterns of inflammatory mediators in hDPSCs induced by LPSs within 24 h. The peaks of all observed inflammatory mediators’ expression are unanimously reached 3–12 h after stimulation by 1 μg/mL E. coli LPS. These results are in line with those of previous studies [17, 42]. The types, concentrations, and stimulation times of stimuli used are different in earlier studies on potential pulp capping agents with anti-inflammatory effects. These differences are not suitable for comparing the anti-inflammatory effects of various potential pulp capping molecules. Our results are beneficial to establishing a baseline level of in vitro model of pulp inflammation to furtherly develop and screen new potential pulp capping agents with outstanding anti-inflammatory quality.

Compared with LPS from P. gingivalis, our results show that only the LPS from E. coli is a potent stimulator of proinflammatory cytokines in hDPSCs, which are in line with many previous studies [51,52,53]. An earlier study describes that the production of IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α from THP-1 cells and human monocytes stimulated by the E. coli LPS are relatively higher than those by the P. gingivalis LPS at 1, 10, 100, 1000, and 10,000 ng/ml [51]. Nebel et al. have compared the IL-6 expression by hPDLCs in response to LPS from E. coli or P. gingivalis and found that only the E. coli LPS is a competent stimulus [24]. Further studies reveal cell-specific response to LPSs of various bacterial origins. In another study, the LPS from E. coli induces strong chemokine and cytokine expression in the gingival fibroblasts, whereas the LPS from P. gingivalis elicits a strong reaction in macrophages [25].

Previous studies showed LPS with a concentration of 1 μg/ml is commonly used as a stimulus to induce inflammation [41, 42]. This concentration was found to be optimal in LPS inducing DPSCs inflammation in a previous study [43]. Our results show that P. gingivalis LPS (1 μg/mL) could not affect the tested inflammatory mediators’ expression in hDPSCs. Previous studies have reported different results exploring the inflammatory response of hDPSCs induced by P. gingivalis LPS [27, 31]. In the study by Ko YJ et al., 1, 5, 10, and 20 μg/mL P. gingivalis LPS significantly elevate the mRNA expression levels of IL-6 and TNF-α in a dose-dependent manner [38]. However, Ko YJ et al. have used P. gingivalis LPS in the laboratory extracted using the phenol/water method, which is different from the commercialized LPS in our study. Using the Northern blot analysis, Chang has demonstrated that P. gingivalis LPS rapidly induces IL-8 and IL-6 in dental pulp stem cells [27]. However, the P. gingivalis LPS in their research is donated by Dr. Arnold, who shows the P. gingivalis LPS is prepared in the laboratory by a hot phenol/water method [54]. Different preparations of LPS result in divergent contents of nucleic acid and protein impurities despite the similarity in structure [55]. Moreover, the expression of inflammatory mediators in the same cells induced by different preparations of LPS can be pretty differentiated [55]. Previous studies show that LPS structures have considerable heterogeneity among various bacterial species and activate host cells differently [33, 56]. The LPS from P. gingivalis is different in structure and function from E. coli [51]. The lipid A of P. gingivalis LPS lacks a phosphate group in the 4′ position and tetradecanoic acids but has long-chain fatty acids. Thus, the endotoxic activity of P. gingivalis LPS is relatively weak [53, 57]. Besides, P. gingivalis LPS is heterogeneous and has several lipid A species, including tri-, tetra-, and penta-acylated lipid As [58]. However, in their laboratory, all kinds of synthetic lipid As of LPS from P. gingivalis cannot induce intense inflammatory responses [57]. Moreover, tri- and tetra-acylated lipid As are even antagonistic in IL-8 and IL-6 expression [57]. Characteristic structures may be the part reason for the low potential of P. gingivalis LPS in inducing the inflammatory response of hDPSCs in our study.

However, Jung et al. show that the same commercialized P. gingivalis LPS from InvivoGen promotes IL-1β and IL-6 mRNA expression in human deciduous dental pulp cells [59], possibly related to the aging heterogeneity of hDPSCs in responses to P. gingivalis LPS. This finding is inconsistent with our results. Gingival fibroblasts show a considerable heterogeneity response to P. gingivalis LPS, which is reflected in increasing IL-6 expression on the mRNA level in gingival fibroblasts from some donors, remaining unchanged in gingival fibroblasts from the other donors [60]. The author speculates that heterogeneity can be due to the host cells’ different genetic backgrounds, ages, genders, and smoking status [60]. The P. gingivalis LPS seems not so stable as an inflammatory stimulus to fibroblasts. In our study, the hDPSCs separated from young permanent teeth rather than deciduous teeth are also a kind of fibroblast. We cannot eliminate the possibility of aging-individual heterogeneity of hDPSCs resulting in the poor bioactivity of P. gingivalis LPS in inducing the inflammatory response of hDPSCs in our study. Besides, the endotoxin activity of P. gingivalis LPS is susceptible to environmental factors, such as ATP, levels of hemin in the culture medium, Mg2+, ambient temperature, and pH [33, 61,62,63,64]. The above factors also may partly explain the inconsistency between the results of these studies.

Previous studies have documented TLRs, particularly TLR2 and TLR4 play a crucial role in regulating the intensity of the immune-inflammatory response during bacterial infection [65, 66]. Our data show that E. coli LPS increases the TLR4 expression level but not TLR2 in hDPSCs, whereas P. gingivalis LPS does not affect TLR4 or TLR2 expression. This result may suggest that the LPS from P. gingivalis may activate neither TLR2 nor TLR4 in hDPSCs and that TLR4 plays a pivotal role in the inflammatory reaction to E. coli LPS in hDPSCs.

TAK-242, a small-molecule derivative of cyclohexene, can selectively inhibit TLR4 signaling [67]. In a previous study, 10 μmol/L TAK-242 exclusively suppresses the TLR4-mediated cytokine production without inhibitory effect on other TLRs, such as TLR2, TLR3, or TLR9 in RAW264.7 cells [68]. In our study, TAK-242 at the same concentration also selectively blocks the activation of TLR4 in hDPSCs treated by E. coli LPS. The expression of all E. coli LPS-induced inflammatory mediators is dramatically suppressed by TAK-242. These data collectively imply that the LPS from E. coli, but not P. gingivalis, is a potent stimulus to propel the production of inflammatory cytokines by hDPSCs via the TLR4 signaling.

However, the current study’s limitations cannot precisely explain the inability of P. gingivalis LPS to elicit inflammatory reactions in hDPSCs in our research. Aside from the structural differences of P. gingivalis LPS caused by different synthetic methods, the interindividual heterogeneities of hDPSCs can be regarded as a possible reason. hDPSCs from volunteers should be collected and classified under differences in age, gender, lifestyle habits (such as smoking status), and genetic background. It would be interesting to determine the hDPSCs from volunteers with different conditions responding to P. gingivalis LPS individually and conclude whether individual differences cause it and reveal its underlying mechanism.

Besides, taking account of P. gingivalis being characteristic of immune escape, P. gingivalis is regarded as a poor inflammatory mediator stimulus [69, 70]. However, it has a solid capability to invade the tissue to avoid the phagocytosis of host immune cells and efficiently cause chronic inflammation [71]. P. gingivalis has been detected in root canal in irreversible pulpitis and periapical periodontitis [72]. P. gingivalis may enter the pulpal tissue through periapical foramen, lateral canal, or dentinal tubules [73]. Studies have shown that root scaling with hand instruments may facilitate bacterial penetration of P. gingivalis through dentinal tubules [74].

As LPS stimulation at early stages of pulp inflammation contributes to migration and differentiation of MSCs [3] leading to possible slowing or arresting or even reversal of pulpitis, the weak inflammatory-inducing compacity of P. gingivalis LPS observed in our study might explain the relatively advanced stages of endodontic lesion in which P. gingivalis has been detected. And, we can not rule out the possibility that the low induction of inflammatory mediators by P. gingivalis LPS in dental pulp may also be due to insufficient activation of the host immune response. So that to escape the monitoring of immune cells, it is easier to enter the pulp tissue for P. gingivalis LPS. Then it is more likely to cause chronic irreversible inflammation. The above hypothesis needs to be elucidated with more data in the future.

In conclusion, our research displays that E. coli LPS is a more stable and more potent stimulus than P. gingivalis LPS in producing inflammatory mediators in hDPSCs. The cytokine expression patterns induced by LPS in hDPSCs may help target treatment for inflammation mediators in pulpitis. Besides, our data suggest that TLR4 acts as an essential signaling intermediate between exogenous E. coli LPS and hDPSCs inflammatory reaction.

Availability of data and materials

The primer sequences generated during the current study are available in the supplementary material. The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to data subject to third party restrictions but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- COX-2:

-

Cyclooxygenase-2

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay

- E. coli :

-

Escherichia coli

- hDPSCs:

-

Human dental pulp stem cells

- hPDLCs:

-

Human periodontal ligament cells

- h:

-

Hour

- GAPDH:

-

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- IL-6:

-

Interleukin-6

- IL-1β:

-

Interleukin-1β

- IL-8:

-

Interleukin-8

- LPS:

-

Lipopolysaccharide

- LPSs:

-

Lipopolysaccharides

- MCP-1:

-

Monocyte chemotactic protein-1

- NF-κB:

-

Nuclear factor kappa B

- P. gingivalis (P.g):

-

Porphyromonas gingivalis

- QRT-PCR:

-

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- TLRs:

-

Toll-like receptors

- TLR4:

-

Toll-like receptor 4

- TLR2:

-

Toll-like receptor 2

- TNF-α:

-

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha

References

Eubanks EJ, Tarle SA, Kaigler D. Tooth storage, dental pulp stem cell isolation, and clinical scale expansion without animal serum. J Endod. 2014;40:652–7.

Kim SG, Zheng Y, Zhou J, Chen M, Embree MC, Song K, et al. Dentin and dental pulp regeneration by the patient’s endogenous cells. Endod Topics. 2013;28:106–17.

Mo IF, Yip KH, Chan WK, Law HK, Lau YL, Chan GC. Prolonged exposure to bacterial toxins downregulated expression of toll-like receptors in mesenchymal stromal cell-derived osteoprogenitors. BMC Cell Biol. 2008;9:52.

Ma D, Gao J, Yue J, Yan W, Fang F, Wu B. Changes in proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of stem cells from deep caries in vitro. J Endod. 2012;38:796–802.

Al Madhoun A, Sindhu S, Haddad D, Atari M, Ahmad R, Al-Mulla F. Dental pulp stem cells derived from adult human third molar tooth: a brief review. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:717624.

Michot B, Casey SM, Gibbs JL. Effects of CGRP-primed dental pulp stem cells on trigeminal sensory neurons. J Dent Res. 2021;100:1273–80.

Chen J, Xu H, Xia K, Cheng S, Zhang Q. Resolvin E1 accelerates pulp repair by regulating inflammation and stimulating dentin regeneration in dental pulp stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12:75.

Ayadilord M, Nasseri S, Emadian Razavi F, Saharkhiz M, Rostami Z, Naseri M. Immunomodulatory effects of phytosomal curcumin on related-micro RNAs, CD200 expression and inflammatory pathways in dental pulp stem cells. Cell Biochem Funct. 2021;39:886–95.

Zhu N, Wang D, Xie F, Qin M, Lin Z, Wang Y. Fabrication and characterization of calcium-phosphate lipid system for potential dental application. Front Chem. 2020;8:161.

Chen W, Guan Y, Xu F, Jiang B. 4-Methylumbelliferone promotes the migration and odontogenetic differentiation of human dental pulp stem cells exposed to lipopolysaccharide in vitro. Cell Biol Int. 2021;45:1415–22.

Cook DN, Pisetsky DS, Schwartz DA. Toll-like receptors in the pathogenesis of human disease. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:975–9.

Underhill DM, Ozinsky A, Smith KD, Aderem A. Toll-like receptor-2 mediates mycobacteria-induced proinflammatory signaling in macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14459–63.

Arbour NC, Lorenz E, Schutte BC, Zabner J, Kline JN, Jones M, et al. TLR4 mutations are associated with endotoxin hyporesponsiveness in humans. Nat Genet. 2000;25:187–91.

Akira S, Takeda K. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:499–511.

Fawzy El-Sayed KM, Klingebiel P, Dorfer CE. Toll-like receptor expression profile of human dental pulp stem/progenitor cells. J Endod. 2016;42:413–7.

Warfvinge J, Dahlen G, Bergenholtz G. Dental pulp response to bacterial cell wall material. J Dent Res. 1985;64:1046–50.

Renard E, Gaudin A, Bienvenu G, Amiaud J, Farges JC, Cuturi MC, et al. Immune cells and molecular networks in experimentally induced pulpitis. J Dent Res. 2016;95:196–205.

Kantrong N, Jit-Armart P, Arayatrakoollikit U. Melatonin antagonizes lipopolysaccharide-induced pulpal fibroblast responses. BMC Oral Health. 2020;20:91.

Nara K, Kawashima N, Noda S, Fujii M, Hashimoto K, Tazawa K, et al. Anti-inflammatory roles of microRNA 21 in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human dental pulp cells. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:21331–41.

He W, Qu T, Yu Q, Wang Z, Lv H, Zhang J, et al. LPS induces IL-8 expression through TLR4, MyD88, NF-kappaB and MAPK pathways in human dental pulp stem cells. Int Endod J. 2013;46:128–36.

Paula-Silva FW, Ghosh A, Silva LA, Kapila YL. TNF-alpha promotes an odontoblastic phenotype in dental pulp cells. J Dent Res. 2009;88:339–44.

Horiba N, Maekawa Y, Matsumoto T, Nakamura H. A study of the distribution of endotoxin in the dentinal wall of infected root canals. J Endod. 1990;16:331–4.

Barthel CR, Levin LG, Reisner HM, Trope M. TNF-alpha release in monocytes after exposure to calcium hydroxide treated Escherichia coli LPS. Int Endod J. 1997;30:155–9.

Nebel D, Arvidsson J, Lillqvist J, Holm A, Nilsson BO. Differential effects of LPS from Escherichia coli and Porphyromonas gingivalis on IL-6 production in human periodontal ligament cells. Acta Odontol Scand. 2013;71:892–8.

Jones KJ, Ekhlassi S, Montufar-Solis D, Klein JR, Schaefer JS. Differential cytokine patterns in mouse macrophages and gingival fibroblasts after stimulation with porphyromonas gingivalis or Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide. J Periodontol. 2010;81:1850–7.

Palaska I, Gagari E, Theoharides TC. The effects of P. gingivalis and E. coli LPS on the expression of proinflammatory mediators in human mast cells and their relevance to periodontal disease. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2016;30:655–64.

Chang J, Zhang C, Tani-Ishii N, Shi S, Wang CY. NF-kappaB activation in human dental pulp stem cells by TNF and LPS. J Dent Res. 2005;84:994–8.

Liu Y, Gao Y, Zhan X, Cui L, Xu S, Ma D, et al. TLR4 activation by lipopolysaccharide and Streptococcus mutans induces differential regulation of proliferation and migration in human dental pulp stem cells. J Endod. 2014;40:1375–81.

Li J, Wang S, Dong Y. Regeneration of pulp-dentine complex-like tissue in a rat experimental model under an inflammatory microenvironment using high phosphorous-containing bioactive glasses. Int Endod J. 2021;54:1129–41.

He W, Wang Z, Zhou Z, Zhang Y, Zhu Q, Wei K, et al. Lipopolysaccharide enhances Wnt5a expression through toll-like receptor 4, myeloid differentiating factor 88, phosphatidylinositol 3-OH kinase/AKT and nuclear factor kappa B pathways in human dental pulp stem cells. J Endod. 2014;40:69–75.

Chung M, Lee S, Chen D, Kim U, Kim Y, Kim S, et al. Effects of different calcium silicate cements on the inflammatory response and odontogenic differentiation of lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human dental pulp stem cells. Materials (Basel). 2019;12:1259.

Chow JC, Young DW, Golenbock DT, Christ WJ, Gusovsky F. Toll-like receptor-4 mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10689–92.

Darveau RP, Pham TT, Lemley K, Reife RA, Bainbridge BW, Coats SR, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide contains multiple lipid A species that functionally interact with both toll-like receptors 2 and 4. Infect Immunol. 2004;72:5041–51.

Hirschfeld M, Ma Y, Weis JH, Vogel SN, Weis JJ. Cutting edge: repurification of lipopolysaccharide eliminates signaling through both human and murine toll-like receptor 2. J Immunol. 2000;165:618–22.

Brodzikowska A, Ciechanowska M, Kopka M, Stachura A, Wlodarski PK. Role of lipopolysaccharide, derived from various bacterial species, in Pulpitis-A Systematic Review. Biomolecules. 2022;12:138.

Liu X, Cao Y, Zhang Y, Sun B, Liang H. Teneligliptin inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced cytotoxicity and inflammation in dental pulp cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 2019;73:57–63.

Lee SI, Kang SK, Jung HJ, Chun YH, Kwon YD, Kim EC. Muramyl dipeptide activates human beta defensin 2 and pro-inflammatory mediators through Toll-like receptors and NLRP3 inflammasomes in human dental pulp cells. Clin Oral Investig. 2015;19:1419–28.

Ko YJ, Kwon KY, Kum KY, Lee WC, Baek SH, Kang MK, et al. The anti-inflammatory effect of human telomerase-derived peptide on P. gingivalis lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory cytokine production and its mechanism in human dental pulp cells. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:385127.

Jin Q, Yuan K, Lin W, Niu C, Ma R, Huang Z. Comparative characterization of mesenchymal stem cells from human dental pulp and adipose tissue for bone regeneration potential. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2019;47:1577–84.

Lei M, Li K, Li B, Gao LN, Chen FM, Jin Y. Mesenchymal stem cell characteristics of dental pulp and periodontal ligament stem cells after in vivo transplantation. Biomaterials. 2014;35:6332–43.

Doyle CJ, Fitzsimmons TR, Marchant C, Dharmapatni AA, Hirsch R, Bartold PM. Azithromycin suppresses P. gingivalis LPS-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine and chemokine production by human gingival fibroblasts in vitro. Clin Oral Investig. 2015;19:221–7.

Liu Z, Jiang T, Wang X, Wang Y. Fluocinolone acetonide partially restores the mineralization of LPS-stimulated dental pulp cells through inhibition of NF-kappaB pathway and activation of AP-1 pathway. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;170:1262–71.

Bindal P, Ramasamy TS, Kasim NHA, Gnanasegaran N, Chai WL. Immune responses of human dental pulp stem cells in lipopolysaccharide-induced microenvironment. Cell Biol Int. 2018;42:832–40.

Elsalhy M, Azizieh F, Raghupathy R. Cytokines as diagnostic markers of pulpal inflammation. Int Endod J. 2013;46:573–80.

Chang MC, Hung HP, Lin LD, Shyu YC, Wang TM, Lin HJ, et al. Effect of interleukin-1beta on ICAM-1 expression of dental pulp cells: role of PI3K/Akt, MEK/ERK, and cyclooxygenase. Clin Oral Investig. 2015;19:117–26.

Park YT, Lee SM, Kou X, Karabucak B. The role of interleukin 6 in osteogenic and neurogenic differentiation potentials of dental pulp stem cells. J Endod. 2019;45:1342–8.

Sabir A, Sumidarti A. TrigonaInterleukin-6 expression on inflamed rat dental pulp tissue after capped with sp. propolis from south Sulawesi, Indonesia. 2017; 24:1034–7.

Song F, Sun H, Wang Y, Yang H, Huang L, Fu D, et al. Pannexin3 inhibits TNF-alpha-induced inflammatory response by suppressing NF-kappaB signalling pathway in human dental pulp cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2017;21:444–55.

Remick DG. Interleukin-8. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:S466–7.

Khorasani MMY, Hassanshahi G, Brodzikowska A, Khorramdelazad H. Role(s) of cytokines in pulpitis: Latest evidence and therapeutic approaches. Cytokine. 2020;126:154896.

Martin M, Katz J, Vogel SN, Michalek SM. Differential induction of endotoxin tolerance by lipopolysaccharides derived from Porphyromonas gingivalis and Escherichia coli. J Immunol. 2001;167:5278–85.

Reife RA, Shapiro RA, Mick GE, Bamber BA, Berry KK, Darveau RP. Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide is poorly recognized by molecular components of innate host defense in a mouse model of early inflammation. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4686–94.

Sun Y, Li H, Sun MJ, Zheng YY, Gong DJ, Xu Y. Endotoxin tolerance induced by lipopolysaccharides derived from Porphyromonas gingivalis and Escherichia coli: alternations in Toll-like receptor 2 and 4 signaling pathway. Inflammation. 2014;37:268–76.

Salvi G, Collins J, Yalda B, Arnold R, Lang N, Offenbacher S. Monocytic TNF alpha secretion patterns in IDDM patients with periodontal diseases. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24:8–16.

Rutledge HR, Jiang W, Yang J, Warg LA, Schwartz DA, Pisetsky DS, et al. Gene expression profiles of RAW264.7 macrophages stimulated with preparations of LPS differing in isolation and purity. Innate Immun. 2012;18:80–8.

Diya Z, Lili C, Shenglai L, Zhiyuan G, Jie Y. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of Porphyromonas gingivalis induces IL-1beta, TNF-alpha and IL-6 production by THP-1 cells in a way different from that of Escherichia coli LPS. Innate Immun. 2008;14:99–107.

Fujimoto Y, Shimoyama A, Saeki A, Kitayama N, Kasamatsu C, Tsutsui H, et al. Innate immunomodulation by lipophilic termini of lipopolysaccharide; synthesis of lipid As from Porphyromonas gingivalis and other bacteria and their immunomodulative responses. Mol Biosyst. 2013;9:987–96.

Sawada N, Ogawa T, Asai Y, Makimura Y, Sugiyama A. Toll-like receptor 4-dependent recognition of structurally different forms of chemically synthesized lipid As of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;148:529–36.

Jung JY, Woo SM, Kim WJ, Lee BN, Nor JE, Min KS, et al. Simvastatin inhibits the expression of inflammatory cytokines and cell adhesion molecules induced by LPS in human dental pulp cells. Int Endod J. 2017;50:377–86.

Andrukhov O, Ertlschweiger S, Moritz A, Bantleon HP, Rausch-Fan X. Different effects of P. gingivalis LPS and E. coli LPS on the expression of interleukin-6 in human gingival fibroblasts. Acta Odontol Scand. 2014;72:337–45.

Al-Qutub MN, Braham PH, Karimi-Naser LM, Liu X, Genco CA, Darveau RP. Hemin-dependent modulation of the lipid A structure of Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide. Infect Immun. 2006;74:4474–85.

Albers U, Tiaden A, Spirig T, Al Alam D, Goyert SM, Gangloff SC, et al. Expression of Legionella pneumophila paralogous lipid A biosynthesis genes under different growth conditions. Microbiology. 2007;153:3817–29.

Suomalainen M, Lobo LA, Brandenburg K, Lindner B, Virkola R, Knirel YA, et al. Temperature-induced changes in the lipopolysaccharide of Yersinia pestis affect plasminogen activation by the pla surface protease. Infect Immun. 2010;78:2644–52.

Xu S, Zhou Q, Fan C, Zhao H, Wang Y, Qiu X, et al. Doxycycline inhibits NAcht Leucine-rich repeat Protein 3 inflammasome activation and interleukin-1beta production induced by Porphyromonas gingivalis-lipopolysaccharide and adenosine triphosphate in human gingival fibroblasts. Arch Oral Biol. 2019;107:104514.

Lorenz E. TLR2 and TLR4 expression during bacterial infections. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12:4185–93.

Liew FY, Xu D, Brint EK, O’Neill LA. Negative regulation of toll-like receptor-mediated immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:446–58.

Takashima K, Matsunaga N, Yoshimatsu M, Hazeki K, Kaisho T, Uekata M, et al. Analysis of binding site for the novel small-molecule TLR4 signal transduction inhibitor TAK-242 and its therapeutic effect on mouse sepsis model. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;157:1250–62.

Ii M, Matsunaga N, Hazeki K, Nakamura K, Takashima K, Seya T, et al. A novel cyclohexene derivative, ethyl (6R)-6-[N-(2-Chloro-4-fluorophenyl)sulfamoyl]cyclohex-1-ene-1-carboxylate (TAK-242), selectively inhibits toll-like receptor 4-mediated cytokine production through suppression of intracellular signaling. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:1288–95.

Ji S, Choi Y. Innate immune response to oral bacteria and the immune evasive characteristics of periodontal pathogens. J Periodontal Implant Sci. 2013;43:3–11.

Palm E, Khalaf H, Bengtsson T. Porphyromonas gingivalis downregulates the immune response of fibroblasts. BMC Microbiol. 2013;13:155.

Ji S, Choi YS, Choi Y. Bacterial invasion and persistence: critical events in the pathogenesis of periodontitis? J Periodontal Res. 2015;50:570–85.

Zargar N, Ashraf H, Marashi SMA, Sabeti M, Aziz A. Identification of microorganisms in irreversible pulpitis and primary endodontic infections with respect to clinical and radiographic findings. Clin Oral Investig. 2020;24:2099–108.

Narayanan LL, Vaishnavi C. Endodontic microbiology. J Conserv Dent. 2010;13:233–9.

Stahli A, Schatt ASJ, Stoffel M, Nietzsche S, Sculean A, Gruber R, et al. Effect of scaling on the invasion of oral microorganisms into dentinal tubules including the response of pulpal cells-an in vitro study. Clin Oral Investig. 2021;25:769–77.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Health Education Joint Research Project, Fujian province (Grant Number: 2019-WJ-14); Startup Fund for scientific research, Fujian Medical University (Grant Number: 2018QH2041).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LCH participated in design of the study, performed the study and drafted the work, CS and JS analyzed and interpreted the collected data. LHX performed the ELISA test. CZY participated in design of the study, reviewed and edited the manuscript. HXJ designed the study, and participated in data analysis, drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Use of human dental tissues was approved by the Ethics Committee of School and Hospital of Stomatology, Fujian Medical University (approval No. 201652) and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All experiments involving human DPSCs were performed in line with the principles laid out in the 2016 ISSCR Guidelines for Stem Cell Research and Clinical Transformation. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1

. The Primer sequences used for QRT-PCR.

Additional file 2: Fig. S1

. Higher concentration of P. gingivalis LPS effect on proinflammatory cytokines in hDPSCs.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Lan, C., Chen, S., Jiang, S. et al. Different expression patterns of inflammatory cytokines induced by lipopolysaccharides from Escherichia coli or Porphyromonas gingivalis in human dental pulp stem cells. BMC Oral Health 22, 121 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-022-02161-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-022-02161-x