Abstract

Background

Ovarian steroid cell tumors (SCTs), not otherwise specified (NOS), are rare, with few large studies. The purpose of this study was to analyze the clinical features, prognosis, and treatment choices for these patients of different age groups.

Methods

This was a retrospective study. We identified nine cases of ovarian steroid cell tumor, not otherwise specified, confirmed by post-operative histopathological examination, and analyzed clinical features, surgical procedures, and follow up outcomes. We also reviewed cases reports of ovarian steroid cell tumors, not otherwise specified.

Results

A total of nine cases were included. The age range was 9–68 years (mean, 41.89 ± 19.72 years). Clinical features included virilization, amenorrhea, abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding, isosexual precocious puberty, Cushing’s syndrome, and abnormal weight gain with elevated testosterone levels. The follow up interval ranged 5–53 months and no recurrence was observed.

Conclusion

Ovarian steroid cell tumors covered all age groups, with manifestations of androgen excess. Younger patients appeared to have a more favorable prognosis, which provided more opportunities for these patients to pursue treatment options that will preserve reproductive function.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ovarian cancers are subdivided into epithelial and non-epithelial counterparts. Non-epithelial ovarian cancers are rare, accounting for approximately 10% of all ovarian cancers and include mainly germ cell tumors, sex cord-stromal tumors, and some extremely rare tumors [1]. Ovarian steroid cell tumors (SCTs) are rare ovarian sex cord stromal tumors that account for less than 0.1% of all ovarian tumors [2]. SCTs occur in females of all ages, causing symptoms such as virilization, isosexual precocious puberty in adolescents, Cushing’s syndrome, and infertility. These clinical manifestations may result from excessive secretion of steroid hormones as well as tumor mass effects. There are three subtypes of SCT, according to cell origin: stromal luteomas, Leydig cell tumors, and not otherwise specified (NOS) tumors [2]. Approximately 60% of SCTs are of the NOS subtype and are usually benign; however, some of these tumors do have malignant behavior, as is observed with peritoneal metastases [3, 4]. Living qualities and fertility are partially associated with the clinical manifestations of SCT-NOS as well as the different treatment options. Here, we describe the clinical characteristics of nine cases of SCT-NOS and review literature reports related to this disease. The aim of this study was to summarize features for diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of ovarian SCT-NOS and provide new clues for future treatment.

We present the following article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist.

Methods

We included all cases diagnosed as ovarian SCT-NOS through histopathological examinations in the Women’s Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine from January 2013 to December 2020. There were 12 retrospective cases, and three of these were excluded because there was a lack of patient history, history of operations at other centers, or because patients were lost to follow up. The remaining nine cases included patients who had received surgical treatment. Clinical records, biological results, histological results, and follow-up information were analyzed for these patients.

Results

Clinical features

For the nine cases analyzed, patient age ranged from 9 to 68 years (mean, 41.89 ± 19.72 years). One patient was premenarchal, four were of reproductive age, and four were postmenopausal. Adnexal masses were the reason for operation in six cases; the other SCTs were incidentally discovered after operations related to endometrial cancers (two cases) or endometriosis (one case).

Most of the nine ovarian SCT patients experienced symptoms of endocrine or metabolic disorders. Three patients presented with virilization symptoms such as hirsutism, acne, and hoarseness; virilization symptoms were alleviated in all patients within 2–3 months. Amenorrhea was observed in two patients along with virilization symptoms. In one patient, regular menses resumed 2 months post-operation, while amenorrhea persisted in the other patient due to administration of gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist (GnRHa) therapy. Two patients reported abdominal pain and one experienced irregular vaginal bleeding. Isosexual precocious puberty presenting as early development of breasts, occurred in one case involving an 9-year-old girl, and was alleviated postoperatively. Five patients were overweight [body mass index (BMI) ≥ 24 kg/m2] and two were obese (BMI ≥ 28 kg/m2); Cushing’s syndrome was observed in one obese patient (Table 1).

Clinical symptoms typically differ based on hormonal secretion, and preoperative serum androgen levels were elevated in most patients. Five patients had abnormal hormone levels. In four patients, serum testosterone (T) levels were increased to 3.8–17.6 nmol/L (normal range, 0.3–3.0 nmol/L). In four patients, preoperative serum dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate (DHEAS) levels were elevated to 8.25–11.8 µmol/L (normal range, 0.96–6.95 µmol/L). Testosterone and DHEAS levels returned to normal postoperatively in two patients (Table 1). One menopausal patient had slightly higher estradiol as well as slightly lower follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) levels (FSH: 34.98 IU/L, LH: 21.89 IU/L, estradiol: 101.9 pmol/L), according to normal menopausal levels (FSH: >40 IU/L, LH: >25 IU/L, estradiol: <100 pmol/L).

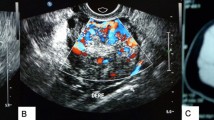

Pelvic masses were found in seven patients. Pelvic ultrasound revealed a heterogeneous mass in five patients, along with lower blood flow resistance index (RI, range 0.31–0.52); one patient exhibited no obvious blood flow signal. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of five patients indicated a T1 isointense and T2 hyperintense mass. The lesions were well enhanced after administration of gadolinium-diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid. Although pelvic masses were present in most patients, one patient did not present with an ovarian mass preoperatively and was ultimately diagnosed by pathology.

Surgical treatment

Four patients underwent bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with or without hysterectomy, and three young patients underwent ovarian tumor resection. Other procedures occurred in only one patient, as described in Table 2. Two cases were diagnosed with SCT-NOS based on histopathological diagnosis without visible ovarian tumors. Tumor diameter ranged from 2 to 5 cm in the other six cases (Table 2). Macroscopic examination revealed yellowish-brown, soft, solid masses in four cases. One case showed a mixture of cystic and solid dark red masses and the other showed a hard, solid mass. Thus, a pelvic mass was a typical sign of SCT-NOS, and surgical resection was an important treatment.

Histopathological features of eight cases are described in Table 2 (Fig. 1). Hemorrhage and nuclear atypia grade II–III were discovered in a 68-year-old patient with endometrial cancer. Nuclear atypia grade II–III was observed alone in a 9-year-old patient. In these cases, neither necrosis nor two or more mitotic cells per 10 high power fields were found.

Follow up

Follow-up time for the nine cases ranged from 5 to 53 months. Disease recurrence had not occurred in any of the cases recently (Table 2).

Discussion

Ovarian SCT-NOS have not been studied across a large number of cases, except for Hayes and Scully’s investigation of 63 cases [2]. We searched PubMed, EBSCO, OVID, and Web of Science for cases of SCT-NOS in English with the search string ((“steroid cell tumor” OR “steroid cell neoplasm”) AND (ovary OR ovaries OR ovarian)) AND (“not otherwise specified” OR “nos”). A total of 329 articles were found, of which 129 were duplicates, 117 were irrelevant, 10 were non-English, and five contained incomplete information. These unmatched articles were excluded and 12 other case reports were added through references. Ultimately, we found 80 articles describing 95 cases of SCT-NOS. We excluded 39 of these cases due to lack of follow-up information or follow-up periods that were too short (less than 3 months), which left 56 cases (Table 3; Fig. 2). We did not include the information from the 63 cases in Hayes and Scully’s article because details were lacking in each of these cases.

Of the 56 cases, the age span of SCT-NOS patients was 3–93 years (median, 33.5 years). Excessive weight gain and virilization features such as hirsutism, acne, baldness, hoarseness, clitoromegaly, along with elevated testosterone were common at any age. For patients of reproductive age, amenorrhea was persistent because of hormonal parasecretion. For premenarchal girls, isosexual precocious puberty and advanced growth affected most. In our cases, virilization manifestations such as hirsutism, acne, and amenorrhea, as well as excessive weight gain were also quite common due to testosterone elevation. Isosexual precocious puberty occurred in one nine-year-old patient from our set of cases, and presented as premature mammary development. Other less common manifestations such as hypertension, abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding, Cushing’s syndrome, and acanthosis nigricans were also reported in the cases analyzed in this study. The symptoms caused by SCT-NOS vanished within 1–16 months post-operation, among the cases with no recurrence. However, Yilmaz and Yokozawa discovered that some changes, including hoarseness, were irreversible even after hormone secretion abnormalities were corrected by tumor elimination [5, 6]. Whether grown adolescent’s height and weight were normalized could not be determined due to lack of follow-up data. A previous study by Bas reported that a 9-year-old SCT-NOS patient had coexistent congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to classic 11 beta-hydroxylase deficiency, and the patient had initial hypertension that progressed and showed hypertensive retinopathy 2 years post-operation [7]. Alves, Faten, and Tai each published cases involving infertility with follow-up periods of 36 months, 12 months, and 24 months, respectively; none of the cases reported successful pregnancy [4, 8, 9]. Data related to infertility were limited due to lack of long-term follow-up. The reported pregnancy rate of non-epithelial ovarian cancer after fertility sparing surgeries varied from 50 to 93%, and live-birth rate was 65-95% [10]. Akimasa and Öz published two gestational SCT-NOS cases with full-term delivery through cesarean, along with unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and the tumor resection, respectively; both two cases underwent a second staging procedure [11, 12]. The reported rate of fetus preservation was 69.4% for gestational patients of ovarian sex-cord stromal tumors who underwent fertility sparing surgeries in the second and third trimesters, and 60.9% patients delivered at term [13]. Some menopausal cases exhibited elevated estradiol as well as low LH and FSH levels, which may have induced endometrial disease from persistent estradiol influence. In our cases, two postmenopausal patients also presented with endometrial adenocarcinoma. Although reproductive hormone levels corresponded with postmenopausal levels in both patients, one also experienced vaginal bleeding until age 65 year. It is suspicious that long-term, persistent estradiol stimulation resulted in vaginal bleeding symptoms, and this suggests the potential presence of STC-NOS along with induced endometrial adenocarcinoma.

Approximately 25–43% SCTs-NOS have malignant potential [2]. The previous study by Hayes and Scully pointed out five pathological features that were correlated with malignancy potential: (1) two or more mitotic fields per 10 high power fields (92% malignant); (2) necrosis (86% malignant); (3) tumor diameter ≥ 7 cm (78% malignant); (4) hemorrhage (77% malignant); and (5) grade II–III nuclear atypia (64% malignant) [2]. Among the 56 cases searched, with the exception of eight cases with missing pathological details, approximately half (28/48) presented with at least one malignant feature. Metastasis was observed in seven cases with primary operation, and at least two malignant pathological features were reported in six cases. Another case was reported according to only one feature. Two other cases showed capsule and vascular infiltration or vascular growth, respectively, and both presented with at least two features. In patients 40 years or younger, the rate of malignant pathological features was 44.83% (13/29), and the rate for patients over 40 years of age was 78.95% (15/19) (P˂0.05, χ2 test). Metastasis, infiltration, and vascular growth occurred in 10.34% (3/29) of the patients 40 years or younger and in 31.58% (6/19) of the patients over 40 (P˃0.05, χ2 test). It seems that SCTs-NOS in patients over the age of 40 are more likely to have malignant behavior. In our cases, a 68-year-old patient experienced hemorrhage and nuclear atypia grade II–III, and a 9-year-old patient presented with nuclear atypia grade II–III. The sample size was limited in this study, and larger scale clinical studies comparing different ages are still needed to provide more conclusive evidence.

Disease recurrence or progression occurred in 10 cases (17.86%) (Table 4). The tumor-free interval ranged from 0 to 108 months, with a median time of 23 months. The age of recurrence ranged from 21 to 93 years, and none of patients younger than 20 years of age reported disease recurrence or progression. The recurrence rate was 11.43% (4/35) for patients aged 40 years or younger, 28.57% (6/21) for those older than 40 years. In the group above 40 years of age, malignant behavior and disease recurrence were more likely to happen. Ascites was a unique manifestation for this group and may serve as an indicator of recurrence following initial therapy. One case that recurred did not report any malignant pathological features, with the longest tumor-free interval of 9 years. Six cases displayed at least two malignant pathological features, whereas three cases displayed only one. The tumor-free interval increased considerably as the feature numbers decreased (Fig. 3).

The reported treatments for disease recurrence or progression in SCT-NOS were tumor excision operations, chemotherapy, and GnRHa therapy. Two recurrent cases received surgery alone, with one reporting 12 months tumor free and a survival time of 16 months. In two reported cases, tumor progression showed no response to chemotherapy alone. Another relapsed case did not respond to chemotherapy but recovered after shifting to GnRHa therapy, and remained tumor free for 22 months. This suggested that for relapsed SCT-NOS patients, GnRHa therapy may be an appropriate choice for adjuvant treatment. Brewer reported a case with aggravated symptoms as well as computed tomography (CT) showing enlarged lymph nodes and uronephrosis during chemotherapy alone after the primary operation; however, the symptoms faded, lymph nodes were diminished, and uronephrosis was improved after switching from chemotherapy to GnRHa [49]. This again indicated an important role for GnRHa as an SCT-NOS adjuvant treatment.

Tumor resections alone were performed in eight patients aged 40 years or younger with no reported disease recurrence. Unilateral salpingo-oophorectomies or oophorectomies were performed in 20 patients aged 40 years or younger, and there were two reports of disease recurrence. These surgeries helped to preserve ovarian function and fertility for young patients with an occurrence rate of 7.14%, which was lower than the overall rate. As discussed above, the malignancy potential and occurrence appeared to be lower in people younger than 40 years and, therefore, surgeries that preserve fertility and ovarian function can be considered when obvious malignant features are absent.

Conclusion

Due to the low incidence of the SCT-NOS, it was difficult to conduct large-scale clinical cohort studies and there was a lack of consistent recommendations for treatment. SCT-NOS are a rare ovarian tumor subtype that can occur at any age. Virilization, weight gain, and amenorrhea with elevated testosterone secretion are common among SCT-NOS patients. Isosexual precocious puberty can also occur in immature girls. Though endocrine abnormalities often recover after surgery, the resulting development effects remain. Therefore, it is important to improve the early diagnosis of this disease to reduce abnormal development caused by endocrine factors as well as relieve anxiety and psychological pressure in younger patients. For older patients, SCT-NOS has malignant potential, and it is important to properly complete pathological assessment because the risk of malignancy and the recurrence rate both increase after age of 40 years. It is of the upmost importance for clinicians to pay careful attention to this phenomenon and effectively manage it. Younger patients have a more favorable prognosis, which provides the chance to consider fertility and ovarian function preserving surgeries.

This study included mostly cases published in public journals, with necessary complete information and prognostic outcomes, between 1991 and 2020. This relatively complete retrospective clinical study provides effective information and value for the diagnosis and treatment of SCT-NOS.

Data Availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- SCT:

-

ovarian steroid cell tumor.

- NOS:

-

not otherwise specified.

- GnRHa:

-

gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist.

- BMI:

-

body mass index.

- T:

-

testosterone.

- DHEAS:

-

dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate.

- FSH:

-

follicle-stimulating hormone.

- LH:

-

luteinizing hormone.

- RI:

-

resistance index.

- MRI:

-

magnetic resonance imaging.

- OTR:

-

ovarian tumor resection.

- RSO:

-

right salpingo-oophorectomy.

- LSO:

-

left salpingo-oophorectomy.

- BSO:

-

bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.

- BS:

-

bilateral salpingectomy.

- HE:

-

hysterectomy.

- EHE:

-

extrafascial hysterectomy.

- OE:

-

omentectomy.

- PLND:

-

pelvic lymph node dissection.

- RPLND:

-

right pelvic lymph node dissection.

- PLNS:

-

pelvic lymph node sampling.

- OER:

-

ovarian endometriotic cyst resection.

- LO:

-

left oophorectomy.

- RO:

-

right oophorectomy.

- BO:

-

bilateral oophorectomy.

- AE:

-

appendectomy.

- TD:

-

tumor debulking.

- NA:

-

not available.

- BEP:

-

bleomycin + etoposide + cisplatin.

- PVB:

-

cisplatin + vincristine + bleomycin.

- TP:

-

paclitaxel + carboplatin.

- CT:

-

computed tomography.

References

Boussios S, Moschetta M, Zarkavelis G, Papadaki A, Kefas A, Tatsi K: Ovarian sex-cord stromal tumours and small cell tumours: Pathological, genetic and management aspects. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology 2017, 120:43–51.

Hayes MC, Scully RE. Ovarian steroid cell tumors (not otherwise specified):a clinicopathological analysis of 63 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1987;11:835–45.

Tan EC, Khong CC, Bhutia K. A rare case of steroid cell tumor, not otherwise specified (NOS), of the Ovary in a Young Woman. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2019;2019:4375839.

Alves P, Sa I, Brito M, Carnide C, Moutinho O. An early diagnosis of an ovarian steroid cell tumor not otherwise specified in a woman. Case reports in obstetrics and gynecology 2019, 2019:2537480–2537480.

Yılmaz-Ağladioğlu S, Savaş-Erdeve Ş, Boduroğlu E, Önder A, Karaman İ, Çetinkaya S, Aycan Z. A girl with steroid cell ovarian tumor misdiagnosed as non-classical congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Turk J Pediatr. 2013;55(4):443–6.

Yokozawa T, Asano R, Nakamura T, Furuya M, Nagashima Y, Koyama-Sato M, Kanda Y, Hirahara F, Sakakibara H. Steroid cell tumour, not otherwise specified: Rare case with primary amenorrhoea in a 16-year-old. J Obstet gynaecology: J Inst Obstet Gynecol. 2015;35(8):867–8.

Bas F, Saka N, Darendeliler F, Tuzlali S, Ilhan R, Bundak R, Gunoz H. Bilateral ovarian steroid cell tumor in congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to classic 11 beta-hydroxylase deficiency. J Pediatr Endocrinol metabolism: JPEM. 2000;13(6):663–7.

Tai YJ, Chang WC, Kuo KT, Sheu BC. Ovarian steroid cell tumor, not otherwise specified, with virilization symptoms. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;53(2):260–2.

Faten H, Dorra G, Slim C, Wajdi S, Nadia C, Kais C, Tahia B, Mohamed A: Ovarian steroid cell tumor (not otherwise specified): a case report of ovarian hyperandrogenism. Case reports in oncological medicine 2020, 2020:6970823.

Bercow A, Nitecki R, Brady PC, Rauh-Hain JA. Outcomes after Fertility-sparing Surgery for Women with Ovarian Cancer: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28(3):527–36.e521.

Akimasa F, Yasuyuki H, Masanobu O, Norio K, Koutarou U, Kazuo S. P1012 An ovarian steroid cell tumor, not otherwise specified with pregnancy causing fetal 46,XX disorder of sex development. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2009;107:697–7.

Oz M, Ozgü E, Türker M, Erkaya S, Güngör T. Steroid cell tumor of the ovary in a pregnant woman whose androgenic symptoms were masked by pregnancy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;290(1):131–4.

Boussios S, Moschetta M, Tatsi K, Tsiouris AK, Pavlidis N. A review on pregnancy complicated by ovarian epithelial and non-epithelial malignant tumors: Diagnostic and therapeutic perspectives. J Adv Res. 2018;12:1–9.

Haroon S, Idrees R, Fatima S, Memon A, Kayani N. Ovarian steroid cell tumor, not otherwise specified: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical experience of 12 cases. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41(3):424–31.

Yoshimatsu T, Nagai K, Miyawaki R, Moritani K, Ohkubo K, Kuwabara J, Tatsuta K, Kurata M, Fukushima M, Kitazawa R, et al. Malignant ovarian steroid cell tumor, not otherwise specified, causes virilization in a 4-year-old girl: a case report and literature review. Case Rep Oncol. 2020;13(1):358–64.

Qian L, Shen Z, Zhang X, Wu D, Zhou Y. Ovarian steroid cell tumor, not otherwise specified: a case report and literature review. Mol Clin Oncol. 2016;5(6):839–41.

Gupta P, Goyal S, Gonzalez-Mendoza LE, Noviski N, Vezmar M, Brathwaite CD, Misra M. Corticotropin-independent cushing syndrome in a child with an ovarian tumor misdiagnosed as nonclassic congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Endocr practice: official J Am Coll Endocrinol Am Association Clin Endocrinologists. 2008;14(7):875–9.

Sawathiparnich P, Sitthinamsuwan P, Sanpakit K, Laohapensang M, Chuangsuwanich T. Cushing’s syndrome caused by an ACTH-producing ovarian steroid cell tumor, NOS, in a prepubertal girl. Endocrine. 2009;35(2):132–5.

Lee SH, Kang MS, Lee GS, Chung WY. Refractory hypertension and isosexual pseudoprecocious puberty associated with renin-secreting ovarian steroid cell tumor in a girl. J Korean Med Sci. 2011;26(6):836–8.

Schnuckle EM, Williamson A, Carpentieri D, Taylor S. Ovarian sex cord stromal tumor, steroid cell, NOS in an adolescent: a case report. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2020;34(1):94–7.

Yuan X, Sun Y, Jin Y, Chen X, Wang X, Ji T, Wang C, Dai H. Ovarian steroid cell tumor, not otherwise specified, treated with surgery: a case report and review of literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2019;12(4):1434–8.

Sielert L, Liu C, Nagarathinam R, Craig L. Androgen-producing steroid cell ovarian tumor in a young woman and subsequent spontaneous pregnancy. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2013;30(9):1157–60.

Jiang W, Tao X, Fang F, Zhang S, Xu C. Benign and malignant ovarian steroid cell tumors, not otherwise specified: case studies, comparison, and review of the literature. J ovarian Res. 2013;6:53.

Santo RE, Sabino T, Agapito A. Ovarian steroid cell tumor not otherwise specified with virilizing manifestations: case report. Acta Obstétrica e Ginecológica Portuguesa. 2016;10(4):336–9.

Zhang X, Lue B. Ovarian steroid cell tumor, not otherwise specified (NOS): an unusual case with myelolipoma. Int J Gynecol pathology: official J Int Soc Gynecol Pathologists. 2011;30(5):460–5.

Matsukawa J, Takahashi T, Hada Y, Kameda W, Ota K, Fukase M, Takahashi K, Matsuo K, Mizunuma H, Nagase S. Successful laparoscopic resection of virilizing ovarian steroid cell tumor, not otherwise specified, in a 22-year-old woman: a case report and evaluation of the steroidogenic pathway. Fukushima J Med Sci. 2019;65(3):133–9.

Arora RMD, Eble JNMD, Pierce HHP, Crispen PLMD, Desimone CPMD, Lee EYMD, Karabakhtsian RGMD. Bilateral ovarian steroid cell tumors and massive macronodular adrenocortical disease in a patient with hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer syndrome. Am J Clin Pathol. 2012;138(suppl_1):A203.

Wong FCK, Chan AZ, Wong WS, Kwan AHW, Law TSM, Chung JPW, Kwok JSS, Chan AOK: Hyperandrogenism, elevated 17-hydroxyprogesterone and its urinary metabolites in a young woman with ovarian steroid cell tumor, not otherwise specified: case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Endocrinol 2019, 2019:9237459.

Menghua Y, Mingcai Q, Mei Z. Symptomatic Cushing syndrome and hyperandrogenemia revealing steroid cell ovarian neoplasm with late intra-abdominal metastasis. BMC Endocr disorders. 2014;14(1):59–72.

Swain J, Sharma S, Prakash V, Agrawal NK, Singh SK. Steroid cell tumor: a rare cause of hirsutism in a female. Endocrinol diabetes metabolism case Rep. 2013;2013:130030.

Li K, Zhu F, Xiong J, Liu F. A rare occurrence of a malignant ovarian steroid cell tumor not otherwise specified: a case report and literature review. Oncol Lett. 2014;8(2):770–4.

Liu A-x, Sun J, Shao W-q. Jin H-m, Song W-q: Steroid cell tumors, not otherwise specified (NOS), in an accessory ovary: a case report and literature review. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;97(1):260–2.

Chung D-H, Lee S-H, Lee K-B. A case of ovarian steroid cell tumor, not otherwise specified, treated with surgery and gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist. J Menopausal Med. 2014;20(1):39–42.

Stephens JW, Fielding A, Verdaguer R, Freites O. A steroid-cell tumor of the ovary resulting in massive androgen excess early in the gonadol steroidogenic pathway. Gynecol endocrinology: official J Int Soc Gynecol Endocrinol. 2008;24(3):151–3.

Ben Haj Hassine MA, Msakni I, Siala H, Rachdi R. Laparoscopic management of an ovarian steroid cell tumor, not otherwise specified causing virilization and amenorrhea: a case report. Case Rep Clin Pathol. 2015;3(1):10–3.

Chen S, Li R, Zhang X, Lu L, Li J, Pan H, Zhu H. Combined ovarian and adrenal venous sampling in the localization of adrenocorticotropic hormone-independent ectopic Cushing syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(3):803–8.

Varras M, Vasilakaki T, Skafida E, Akrivis C. Clinical, ultrasonographic, computed tomography and histopathological manifestations of ovarian steroid cell tumour, not otherwise specified: our experience of a rare case with female virilisation and review of the literature. Gynecol endocrinology: official J Int Soc Gynecol Endocrinol. 2011;27(6):412–8.

Zang L, Ye M, Yang G, Li J, Liu M, Du J, Gu W, Jin N, Yang L, Ba J, et al. Accessory ovarian steroid cell tumor producing testosterone and cortisol: a case report. Medicine. 2017;96(37):e7998.

Kim JS, Park SN, Kim BR. Recurrent ovarian steroid cell tumor, not otherwise specified managed with debulking surgery, radiofrequency ablation, and adjuvant chemotherapy. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2014;57(6):534–8.

Reedy MB, Richards WE, Ueland F, Uy K, Lee EY, Bryant C, van Nagell JR Jr. Ovarian steroid cell tumors, not otherwise specified: a case report and literature review. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;75(2):293–7.

Lee J, John VS, Liang SX, D’Agostino CA, Menzin AW: Metastatic malignant ovarian steroid cell tumor: a case report and review of the literature. Case reports in obstetrics and gynecology 2016, 2016:6184573.

Wang PH, Chao HT, Lee RC, Lai CR, Lee WL, Kwok CF, Yuan CC, Ng HT. Steroid cell tumors of the ovary: clinical, ultrasonic, and MRI diagnosis - a case report. Eur J Radiol. 1998;26(3):269–73.

Nakasone T, Nakamoto T, Matsuzaki A, Nakagami H, Aoki Y. Direct evidence on the efficacy of GnRH agonist in recurrent steroid cell tumor-not otherwise specified. Gynecologic Oncol Rep. 2019;29:73–5.

Chun YJ, Choi HJ, Lee HN, Cho S, Choi JH. An asymptomatic ovarian steroid cell tumor with complete cystic morphology: a case report. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2013;56(1):50–5.

Kim YT, Kim SW, Yoon BS, Kim SH, Kim JH, Kim JW, Cho NH. An ovarian steroid cell tumor causing virilization and massive ascites. Yonsei Med J. 2007;48(1):142–6.

Cooray SMA, Bulugahapitiya UDS, Samarasinghe K, Samarathunga P. Steroid cell tumor not otherwise specified of bilateral ovaries: a rare cause of post menopausal virilization. Indian J Endocrinol Metabol. 2013;17(Suppl 1):262–4.

Faraj G, Di Gregorio S, Misiunas A, Faure EN, Villabrile P, Stringa I, Petroff N, Bur G. Virilizing ovarian tumor of cell tumor type not otherwise specified: a case report. Gynecol endocrinology: official J Int Soc Gynecol Endocrinol. 1998;12(5):347–52.

Abdullah LS. Ovarian steroid cell tumor, NOS presenting with massive ascites and elevated CA-125. JKAU Med Sci. 2011;18(3):107–14.

Brewer CA, Shevlin D. Encouraging response of an advanced steroid-cell tumor to GnRH agonist therapy. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92(4 Pt 2):661–3.

Sedhom R, Hu S, Ohri A, Infantino D, Lubitz S. Symptomatic Cushing’s syndrome and hyperandrogenemia in a steroid cell ovarian neoplasm: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2016;10(1):278.

Stephens JW, Katz JR, McDermott N, MacLean AB, Bouloux PM. An unusual steroid-producing ovarian tumour: case report. Hum Reprod (Oxford England). 2002;17(6):1468–71.

Singh P, Deleon F, Anderson R. Steroid cell ovarian neoplasm, not otherwise specified: a case report and review of the literature. Case reports in obstetrics and gynecology 2012, 2012:253152.

Powell JL, Dulaney DP, Shiro BC. Androgen-secreting steroid cell tumor of the ovary. South Med J. 2000;93(12):1201–4.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number LY21H160032), and the Key research and development program of Zhejiang province (grant number 2019C03010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MYL and KCB contributed equally to this work. MYL, KCB and FFW designed the study, analyzed the patients’ data, searched literatures, and drafted the manuscript. LJL and SHX participated in collecting the patients’ data and searching literatures. XDC reviewed the final manuscript. YL checked the histological examination of the steroid cell tumors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by Ethics Committee of Women’s Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University (IRB-20210092-R).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

† Mengyan Lin and Kechun Bao are co-first authors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, M., Bao, K., Lu, L. et al. Ovarian steroid cell tumors, not otherwise specified: analysis of nine cases with a literature review. BMC Endocr Disord 22, 265 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-022-01170-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-022-01170-9