Abstract

Background

Steroid cell tumors (SCTs) are very rare sex cord-stromal tumors and account only for less than 0.1% of ovarian neoplasms. SCTs might comprise diverse steroid-secreting cells; hence, the characteristic clinical features were affected by their propensity to secrete a variety of hormones rather than mass effect resulting in compression symptoms and signs. To date, ovarian SCTs have seldom been reported in children, particularly very young children; and pseudoprecocious puberty (PPP) as its unique principal manifestation should be reiterated.

Case presentation

We reported a 1-year-8-month-old girl presenting with rapid bilateral breast and pubic hair development within a 2-month period. Undetectable levels of LH and FSH along with excessively high estradiol after stimulation with gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), as well as a heterogeneous mass inside left ovary shown in pelvic sonography indicate isosexual PPP. Her gonadal hormones returned remarkably to the prepubertal range the day after surgery, and histology of the ovary mass demonstrated SCTs containing abundant luteinized stromal cells.

Conclusion

The case highlighted that SCTs causing isosexual PPP should be taken into consideration in any young children coexistent with rapidly progressive puberty given a remarkable secretion of sex hormones. This article also reviewed thoroughly relevant reported cases to enrich the clinical experience of SCTs in the pediatric group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Precocious puberty is defined as the appearance of physical and hormonal signs of pubertal development before the age of 8 years in girls and 9 years in boys [1]. Etiologically, central precocious puberty (CPP) caused by early activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis (HPG axis) is noticeably different from pseudoprecocious puberty (PPP) caused by endogenous sex-hormone producing tumors or exogenous hormone exposure [1]. Over 90% of the girls with CPP is idiopathic; while patients with PPP have a high risk of neoplasm existence which is a pivotal culprit for young children exhibiting rapidly progressive sexual precocity [1]. In view of this, diverse PPP-associated manifestations should be underscored to prevent delayed diagnosis and ensure the early management.

SCTs are rare tumors and account only for less than 0.1% ovarian neoplasms [2]. Histologically, they can be divided into several subtypes, such as stromal luteoma, Leydig cell tumor, or SCTs- not otherwise specified (NOS), according to their cell components [2]. Among them, SCTs-NOS make up approximately 56% of ovarian SCTs and most of the affected patients were adults with an average diagnostic age of 43 years [2]. SCTs-NOS can secrete a variety of steroid hormones; thus their clinical manifestations in adults are nonspecific and pleomorphic, including virilization or hirsutism, amenorrhea, hypercalcemia, erythrocytosis, ascites and Cushing’s syndrome in adults [2]. On the contrary, clinical experience in managing affected children was limited, which may result in delayed diagnosis and inappropriate treatment. To date, only a few children cases of SCTs-NOS have been reported, and isosexual PPP as the unique presentation has not been much emphasized.

We reported a very young girl presenting with bilateral breast and pubic hair development within a 2-month period. A heterogeneous hypoechoic cystic mass was found over her left ovary, which was histopathologically confirmed to be SCTs-NOS. After surgical removal, breast development remitted and her gonadal hormone also returned to the prepubertal range, revealing that SCTs-NOS could be effectively managed with surgical intervention upon prompt and precise diagnosis. Moreover, the present article also reviewed and integrated relevant cases from the literature to enrich the clinical experience of approaching SCTs, particularly in children.

Case presentation

A 1-year-8-month-old girl was brought to the endocrinology outpatient clinic due to abrupt bilateral breast development and rapid growth velocity (2.0 cm/month) within 2 months. She had no perinatal or morbid records of relevance, and no use of medicine or products with phytoestrogens. On examination, her body length was 87.5 cm (90-97th percentile) and body weight was 11.3 kg (50-75th percentile). Bilateral breast showed Tanner stage III with nipple hyperpigmentation. Her pubic hair development was at Tanner stage III but there was no axillary hair development. In addition, there was no café-au-lait spots. Endocrine function test disclosed excessively high estradiol (E2) level with undetectable FSH and LH values (Table 1). Bone age study was read between 2 years old and 2 years and 6 months old at her chronological age of 1 year and 8 months.

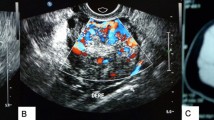

She was then admitted for further evaluation due to precocious puberty. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) stimulation test revealed complete suppression of baseline and peak values of LH and FSH (all < 0.1 IU/L), while baseline and peak values of E2 were 1859.5 pmol/L and 1796.4 pmol/L, respectively (Table 1), implying estrogenic development without activation of the HPG axis. Furthermore, serum tumor markers all disclosed normal. Pelvic ultrasound showed uterus size of 3.57 × 1.47 × 1.96 cm (estimated volume 5.38 cm3; normal: 1.05 cm3 on average). Right ovary was 0.96 × 0.50 cm in size with few small follicles, and left ovary was 2.93 × 1.79 cm in size with a heterogeneous hypoechoic cystic mass of 1.86 × 1.39 cm in size inside (Fig. 1A). Therefore, she was diagnosed as isosexual PPP on the basis of suppressed gonadotropin response to GnRH stimulation test and left ovarian mass lesion. Laparoscopic-assisted left salpingo-oophorectomy was performed. Grossly, the tumor was circumscribed and the cut surface reveals nodularity (Fig. 1B). Its color was golden-yellowish with hemorrhagic content. Microscopically, the tumor cells were polygonal with abundant cytoplasm ranging from vacuolated (lipid-rich) to eosinophilic (lipid-poor) (Fig. 1C). The nuclei were typical round with a prominent central nucleolus. The stroma ranged from scant to prominent with fibrous bands and conspicuous vasculature. Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells showed positive staining for alpha-inhibin (Fig. 1D) and adipophilin (not shown), confirming its nature of a sex cord-stromal tumor with steroid secreting.

Clinical image of patient and gross and histological features of SCTs. A. Ultrasound showed left ovary of 2.93 × 1.79 cm in size with a heterogeneous hypoechoic cystic mass of 1.86 × 1.39 cm in size inside. B. Circumscribed tumor with golden-yellowish cut surface and hemorrhagic content. C. Tumor cells showed two cell populations of clear (left-upper) and eosinophilic cytoplasm (right-lower). D. Immunohistochemical features of SCTs. Positive alpha-inhibin stain, indicating a sex cord-stromal tumor. (HE, original magnification: C × 200; D × 400)

One day after operation, baseline gonadal function still showed suppressed levels of gonadotropin (both FSH and LH < 0.10 IU/L), but E2 value was undetectable dramatically (< 18.4 pmol/L). Five months later, physical examination revealed bilateral breast development at Tanner stage II and disappearance of pubic hair. Follow-up pelvic ultrasound revealed a shrunk uterus of size 2.41 × 1.15 × 1.49 cm (estimated volume 2.16 cm3), no specific findings in left ovary, and right ovary 1.25 × 1.01 cm with few antral follicles, indicating salient improvement of pubertal progression after resection of the ovarian tumor.

Discussion and conclusions

Ovarian SCTs are uncommon tumors first brought up by Heyes et al. in 1987, which could occur at any age even mostly found in adults [2]. To date, children cases of ovarian SCTs were scanty and their associated presentations had not been stressed, which might lead to delayed diagnosis in such young patients. Given that SCTs comprise diverse cells secreting steroid hormones, their clinical features are usually in line with secretory hormones rather than tumor mass effect. In view of this, high levels of 17-hydroxyprogesterone (17-OHP), androstenedione, and testosterone could be detected in patients with virilization and hirsutism, while increased values of E2 and cortisol were associated with isosexual PPP and Cushing’s syndrome, respectively [2]. Although adult women accounted for most reported SCTs and virilization was thought to be the most common symptom, the lack of rich clinical experience and the low awareness of isosexual PPP in children might contribute to unnecessary examination and parental anxiety. Herein, we present the youngest girl in current literature exhibiting early breast development before 2 years old, and finally diagnosed with SCTs causing isosexual PPP based on suppressed gonadotropin levels on GnRH test and typical histological findings. This case highlighted the discrepancy of clinical manifestations between adults (mainly virilization) and very young children (early feminization). However, further studies on more cases of different ages are warranted to confirm our aforementioned findings.

Among SCTs adults, more than half of them presented with hyperandrogenic signs such as hirsutism, acne, deepened voice, clitoromegaly, amenorrhea, and infertility [3]. Only a few remaining cases exhibited hyperestrogenism in terms of menorrhagia, postmenopausal bleeding, sometimes even endometrial cancer [3]. Nevertheless, reported cases in children were so scarce that their typical features remained elusive. For better understanding, previously reported children cases of SCTs (n = 15) were thoroughly reviewed (Table 2) [2, 4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. After excluding the three cases without documented clinical manifestation and one case presenting only with mass effect, a total of 12 patients including the present case were analyzed (Table 3) [4,5,6,7,8, 10,11,12,13,14,15]. Most of them showed heterosexual precocity (66%) with symptoms of virilization (50%), hirsutism (25%), amenorrhea (17%), hypertrichosis (17%), facial acnes (17%) and temporal balding (8%). On the contrary, isosexual precocity accounted for only 33% of all cases and the predominant symptoms were early breast development (33%), followed by vaginal bleeding (25%) and nipple pigmentation (8%). Other non-specific symptoms irrelevant to sex hormone included Cushing’s syndrome (33%) and hypertension (17%)(Table 3) [4,5,6,7,8, 10,11,12,13,14,15]. Herein, improved understanding of aforementioned features will add a new dimension to the precise management of ovarian SCTs.

Of note is that all reviewed cases aged less than 3 years presented with isosexual precocity except case No. 5, implying the younger the patient, the higher the possibility isosexual PPP occurrence [4,5,6,7]. Even though functioning follicular cysts are the most common cause of PPP in girls [16], this cause was excluded in our case in view of a heterogeneous hypoechoic cystic mass of ovary. Furthermore, no café-au-lait skin spots also did not support the diagnosis of McCune-Albright syndrome [17]. Therefore, a comprehensive differential diagnosis is still crucial to rule out the rare etiology such as SCTs in extremely young children. On the other hand, the patients with SCTs could present with androgenization or estrogenization, but masculinization is still the predominant symptom, especially in adults. These findings can be accounted for by the higher testosterone than E2 levels observed in a large proportion of our reviewed cases (Table 2) [2, 4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. In contrast, the present young girl had suppressible serum LH and FSH levels along with extremely high E2, indicating inactivation of the HPG axis and also echoing hypersecretion of estrogen caused by SCTs.

In addition to clinical manifestations and endocrine data, image studies such as sonography, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) also played a pivotal role in the diagnosis of SCTs [18]. Although typical characteristics of CT and MRI are divergent depending on lipid components and fibrous stroma, SCTs usually revealed intense enhancement reflecting hypervascularity and hypointense nodular wall attributed to lipid contents [18]. Pelvic ultrasound could disclose a well-defined echogenic mass over ovaries [19]. As for immunopathology, SCTs revealed tumor cells with both eosinophilic and vacuolated cytoplasm, surrounded with fibrous stroma, as well as positive staining for alpha-inhibin and adipophilin [2]. In the present case, a heterogeneous hypoechoic cystic mass over left ovary was detected via pelvic sonography, which microscopically revealed multiple composition of lipid, fibrous tissue and vessels, as well as positive staining for alpha-inhibin and adipophilin along with clear and eosinophilic cytoplasm in the tumor specimen. SCTs could become malignant and subsequent adjuvant chemotherapy might be necessary after surgery [8, 20]; nonetheless, most of the cases had significantly good outcomes with marked decrease in sex hormones the first day after surgical resection as in our case. As expected, clinical symptoms of SCTs could remit a few months later. In summary, SCTs are rare tumors but usually benign [3, 8], and could be effectively managed with surgical intervention when prompt and precise diagnosis was made.

The present case highlighted the distinctive feature of isosexual PPP caused by SCTs in children especially those younger than 3 years of age, which was notably different from adults mainly presenting with virilization. Although the most common etiology of isosexual precocity is CPP, a high index of suspicion of peripheral lesions and detailed endocrine function tests are important for early diagnosis and treatment of rare SCTs.

Availability of data and materials

All the data generated and/or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- 17-OHP:

-

17-hydroxyprogesterone

- ACTH:

-

Adrenocorticotropic hormone

- AFP:

-

Alpha-fetoprotein

- β-HCG:

-

β-subunit human chorionic gonadotropin

- CA-125:

-

Cancer antigen 125

- CA19–9:

-

Carbohydrate antigen 19–9

- CPP:

-

Central precocious puberty

- C/T:

-

Chemotherapy

- Cl-:

-

Chloride

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- DHEA-S:

-

Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate

- E2:

-

Estradiol

- FSH:

-

Follicle-stimulating hormone

- GnRH:

-

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone

- HP:

-

Heterosexual precocity

- HPG axis:

-

Hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis

- IFG-1:

-

Insulin-like growth factor 1

- IP:

-

Isosexual precocity

- LDH:

-

Lactate dehydrogenase

- LH:

-

Luteining hormone

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NSE:

-

Neuron specific enolase

- NOS:

-

Not otherwise specified

- K + :

-

Potassium

- PPP:

-

Pseudoprecocious puberty

- SO:

-

Salpingo-oophorectomy

- Na + :

-

Sodium

- SCT:

-

Steroid cell tumor

- FT4:

-

Free thyroxine

- T4:

-

Thyroxine

- TSH:

-

Thyroid-stimulating hormone

References

Colaco P. Precocious puberty. Indian J Pediatr. 1997;64(2):165–75.

Hayes MC, Scully RE. Ovarian steroid cell tumors (not otherwise specified). A clinicopathological analysis of 63 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1987;11(11):835–45.

Vasilevska D, Rudaitis V, Vasilevska D, Mickys U, Wawrysiuk S, Semczuk A. Failure of multiple surgical procedures and adjuvant chemotherapy in early-stage steroid-cell ovarian tumor treatment: a case report and literature review. J Int Med Res. 2021;49(1):0300060520983195.

Haroon S, Idrees R, Fatima S, Memon A, Kayani N. Ovarian steroid cell tumor, not otherwise specified: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical experience of 12 cases. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41(3):424–31.

Lin CJ, Jorge AA, Latronico AC, Marui S, Fragoso MCV, Martin RM, et al. Origin of an ovarian steroid cell tumor causing isosexual pseudoprecocious puberty demonstrated by the expression of adrenal steroidogenic enzymes and adrenocorticotropin receptor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(3):1211–4.

Lee SH, Kang MS, Lee GS, Chung WY. Refractory hypertension and isosexual pseudoprecocious puberty associated with renin-secreting ovarian steroid cell tumor in a girl. J Korean Med Sci. 2011;26(6):836–8.

Hellyanti T, Sitinjak D. Ovarian steroid cell tumour (NOS) causing Cushing's syndrome in an extremely young girl: a case report. J Pak Med Assoc. 2021;71(2):S146–50.

Yoshimatsu T, Nagai K, Miyawaki R, Moritani K, Ohkubo K, Kuwabara J, et al. Malignant ovarian steroid cell tumor, not otherwise specified, causes virilization in a 4-year-old girl: a case report and literature review. Case Rep Oncol. 2020;13(1):358–64.

Qian L, Shen Z, Zhang X, Wu D, Zhou Y. Ovarian steroid cell tumor, not otherwise specified: a case report and literature review. Mol Clin Oncol. 2016;5(6):839–41.

Gupta P, Goyal S, Gonzalez-Mendoza LE, Noviski N, Vezmar M, Brathwaite CD, et al. Corticotropin-independent Cushing syndrome in a child with an ovarian tumor misdiagnosed as nonclassic congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Endocr Pract. 2008;14(7):875–9.

Sawathiparnich P, Sitthinamsuwan P, Sanpakit K, Laohapensang M, Chuangsuwanich T. Cushing’s syndrome caused by an ACTH-producing ovarian steroid cell tumor, NOS, in a prepubertal girl. Endocrine. 2009;35(2):132–5.

Harris A, Wakely P Jr, Kaplowitz P, Lovinger R. Steroid cell tumor of the ovary in a child. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1991;115(2):150–4.

Yılmaz-Ağladıoğlu S, Savaş-Erdeve Ş, Boduroğlu E, Önder A, Karaman İ, Çetinkaya S, et al. A girl with steroid cell ovarian tumor misdiagnosed as non-classical congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Turk J Pediatr. 2013;55(4):443–6.

Boyraz G, Selcuk I, Yusifli Z, Usubutun A, Gunalp S. Steroid cell tumor of the ovary in an adolescent: a rare case report. Case Rep Med. 2013;2013:527698.

Ding D-C, Hsu S. Lipid cell tumor in an adolescent girl: a case report. J Reprod Med. 2007;52(10):956–8.

Chae HS, Rheu CH. Precocious pseudopuberty due to an autonomous ovarian follicular cyst: case report with a review of literatures. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6(1):319.

Dumitrescu CE, Collins MT. McCune-Albright syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2008;3(1):12.

Saida T, Tanaka Y, Minami M. Steroid cell tumor of the ovary, not otherwise specified: CT and MR findings. Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188(4):W393–4.

Wang P-H, Chao H-T, Lee R-C, Lai C-R, Lee W-L, Kwok C-F, et al. Steroid cell tumors of the ovary: clinical, ultrasonic, and MRI diagnosis—a case report. Eur J Radiol. 1998;26(3):269–73.

Swain J, Sharma S, Prakash V, Agrawal N, Singh S. Steroid cell tumor: a rare cause of hirsutism in a female. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. 2013;2013(1):130030.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by Tri-Service General Hospital, Taiwan (TSGH-E-110187 and TSGH-E-111196 to C-M Lin), and the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST107–2314-B-016-064-MY3 and MOST110–2314-B-016-016-MY3 to C-M Lin). The funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CHC conceptualized the study, collected data, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. WDW, SYW, TKC, RYS collected data, carried out the initial analyses, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. CML conceptualized the study, coordinated and supervised data collection, and provided critical editing and revision to the final drafts of the report. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This article was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institutional Review Board of Tri-Service General Hospital, National Defense Medical Center.

Consent for publication

The patient and her parents agreed to the use of her clinical data for publication and academic research and provided written informed consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Chu, CH., Wang, WD., Wang, SY. et al. Ovarian steroid cell tumor causing isosexual pseudoprecocious puberty in a young girl: an instructive case and literature review. BMC Endocr Disord 22, 41 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-022-00956-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-022-00956-1