Abstract

Background

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is becoming increasingly popular as a treatment for precancerous lesions and early cancers of the stomach. However, there have been few studies on the factors associated with the recurrence of precancerous lesions after ESD.

Methods

To investigate the prognostic factors of gastric intraepithelial neoplasia, we retrospectively analyzed 115 patients who were treated with ESD between February 2018 and January 2020. Chi-square test and Fisher’s extract test were used to select factors for further investigation, and prognostic analysis was carried out with the Kaplan–Meier method and a Cox regression model.

Results

Platelet counts (P = 0.027) and albumin levels (P = 0.011) were both lower in patients with recurrence than in patients without recurrence of gastric mucosal atypical hyperplasia after ESD.

Conclusions

This study reveals that low platelet counts and albumin levels were probably unfavorable prognostic factors in mucosal atypical hyperplasia of the stomach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Atypical hyperplasia presenting in the gastric mucosa is a type of precancerous lesion of gastric cancer. The results of a large Dutch cohort study of patients with a first diagnosis of precancerous gastric lesions showed that the annual incidence of gastric cancer was 0.1%, 0.25%, 0.6%, and 6% in the groups with atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, mild–moderate atypical hyperplasia, and severe atypical hyperplasia, respectively [1]. Another prospective study in Italy with a mean follow-up of 14 years showed a cancer rate of 8.9% and 68.7%, respectively, for mild–moderate, and severe atypical hyperplasia [2]. Therefore, in view of the above risks, the treatment of gastric atypical hyperplasia is very necessary. The positive detection rate of atypical hyperplasia has been rising as endoscopy has become more common. Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) can be used to treat precancerous lesions and early cancers, and has the advantages of a large resection range, access to the whole specimen, and ease of pathological evaluation [3, 4]. Many studies have explored the prognosis of early gastric cancer after ESD treatment [5, 6]. A large follow-up study found that H. pylori, smoking and low levels of dietary vitamin C were associated with the risk of progression to gastric atypical hyperplasia [7]. However, there has been little research on the factors associated with the recurrence of gastric mucosal atypical hyperplasia after ESD. If the recurrence of atypical hyperplasia in the gastric mucosa can be reduced, the incidence of early gastric cancer will be reduced accordingly, which is of great clinical interest. Therefore, we conducted this study to explore the risk factors for atypical hyperplasia recurrence after ESD, aiming to make better recommendations and improve the prognosis for patients with the above diseases.

Materials and methods

Patients and study design

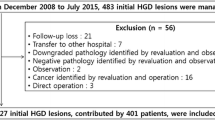

The inclusion criteria for patients were the following: (1) Total removal of the lesion through ESD; (2) atypical hyperplasia confirmed by postoperative pathology; and (3) negative pathological margins. The exclusion criteria were blood dyscrasias, systemic inflammatory disease, autoimmune disease, liver disease, renal disease, thyroid disease/cancer, and medical treatment with an anticoagulant. Nine patients who were diagnosed with gastric cancer including carcinoma in situ were also excluded, and 10 patients were lost to follow-up. Ultimately, 115 patients who received ESD treatment from February 2018 and January 2020 (48 months) at The First People’s Hospital of Xiaoshan District, China were included in this study.

All patients received ESD treatment from experienced digestive physicians. Intraoperative and postoperative complications such as bleeding and perforation received timely and effective treatment. All the lesions were completely resected, and the margins were all negative.

The follow-up time was from the day of ESD treatment until January 31, 2022. We required that included patients had at least 12 months of follow up and 2 or more endoscopic findings, or did not meet the above inclusion criteria but had pathological findings of atypical hyperplasia on endoscopy during follow-up. The median follow-up duration was 30 months. Most patients were followed up every 3 to 6 months with a gastroscopy review. We defined recurrence as the endoscopic pathology of the original lesion site of atypical hyperplasia in a subsequent review. The times to recurrence or death were analyzed as end events.

Because our study was retrospective and patients’ medical records were reviewed from February 2018 and January 2020, it was difficult to obtain patients’ informed consent. Since our research method had a very low risk, the Institutional Review Board of The First People’s Hospital of Xiaoshan District approved our research without requiring consent.

Clinical characteristics and biochemical measurements

We first collected the clinical characteristics for all patients, including sex, age, lesion morphology and pathological grade, and then evaluated the biochemical indicators. Venous blood samples were taken from patients after a morning fast within 5 days before surgery. Whole blood samples were collected in a special blood collection tube, and all blood samples were processed in a short time. The white blood cell (WBC), neutrophil, lymphocyte, platelet and albumin levels and blood types were measured with a blood analyzer. The inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variation for all assays were less than 5%. We recorded the patients’ histopathological information, including the lesion morphology and degree, atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia. Positive for H. pylori infection using histocytological Jimsa staining. We included bleeding and en bloc resection as variables, and en bloc resection was defined as the removal of the lesion completely with negative margins. Finally, we also collected information about the patient’s health, expressed in American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score.

The neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio (NLR) was calculated as the absolute neutrophil count divided by the measured absolute lymphocyte count. The platelet/lymphocyte ratio (PLR) was calculated as the absolute platelet count divided by the measured absolute lymphocyte count. The ideal cut-off values for the NLR, PLR, platelet count, albumin level, etc. were obtained from their mean values.

Statistical analysis

Baseline data were obtained from the electronic medical records of our hospital. Endoscopic pathology information that could not be reviewed in our hospital was obtained by telephone follow-up. Student’s t test was used to compare the non-categorical variables of the two groups. Chi-square tests and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare categorical variables and for the initial screening of recurrence factors, then the Kaplan–Meier method was used for further assessment of the recurrence rate. Variables with P values < 0.05 were included in a multivariate Cox hazards regression model with a regression elimination strategy. A two-tailed P-value < 0.05 was set as the statistical significance threshold. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS Version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

In total, 115 patients were enrolled in our study, including 77 male patients and 38 female patients, and the median age was 61.0 ± 10.0 years (range 36–89). The patients’ lesions ranged from 5 to 50 mm in maximum diameter (14.9 ± 8.4 mm) and located on upper third of stomach in 9 patients, middle third in 14 patients and lower third in 92 patients. The rate of en bloc resection was 93.0% (107/115) and the unsuccessful en bloc resection rate was 7.0% (8/115). Six patients emerged bleeding during the procedure and all received effective hemostasis. Seven patients developed fever and 31 patients developed abdominal pain in the postoperative period. The median time to follow-up was 30 months, with a range of 3 to 48 months (interquartile range (IQR) = 26–37 months). During the follow-up period, 19 patients relapsed. In addition, in the pathology review, two patients were found to have atypical hyperplasia far from the primary site, but these were categorized into the non-recurrence group. Only one patient died, but the cause of death was unknown. The clinicopathological characteristics of the patients with and without recurrence are shown in Table 1.

We next evaluated biochemical indicators in patients’ blood samples, and grouped patients accordingly. The platelet data were normally distributed (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test P = 0.95), the mean platelet count was 207.9 × 109/L. Means can better represent the characteristics of the data, so we selected the mean platelet count (207.9 × 109/L) as the cut-off value to divide the patients into two groups. Of the 115 patients, 57 had platelet counts less than 207.9 × 109/L and 58 had platelet counts greater than 207.9 × 109/L. The same method was applied to other non-categorical variables, including the WBC count, NLR, PLR and albumin level. There were no statistically significant differences between the recurrence and non-recurrence groups in terms of age, sex ratio, tumor morphology, pathological grade, NLR, PLR, WBC, bleeding, en bloc resection, H. pylori, atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia and ASA score. However, the platelet counts (P = 0.027) and albumin levels (P = 0.011) differed significantly between patients with and without recurrence.

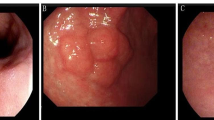

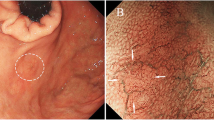

The recurrent lesions consisted of severe atypical hyperplasia (5 cases, 26.3%) and mild–moderate atypical hyperplasia (14 cases, 73.7%). Endoscopic findings in recurrent patients showed 5 lesions to be ulcerated, 8 lesions to be elevated and 6 lesions to be erosive. Of the patients who relapsed, two patients received a second ESD treatment after learning the results. The median time to recurrence was 7 months, with a range of 3 to 40 months (IQR = 3–12 months). The median number of endoscopies is 3 times, with a range of 1 to 6 times (IQR = 3–4 times). We used the Kaplan–Meier method to calculate the cumulative incidence of recurrence in the high-platelet and low-platelet groups. The cumulative incidence of recurrence was higher in the low-platelet group than in the high-platelet group (P = 0.016, Fig. 1). We also used the Kaplan–Meier method to analyze the cumulative incidence of recurrence according to albumin levels. The risk of recurrence was higher in the low-albumin group than in the high-albumin group (P = 0.013, Fig. 2). Finally, Cox factor regression analysis demonstrated that albumin levels and platelet counts were independent prognostic factors in gastric mucosal atypical hyperplasia patients (Table 2).

Discussion

This study demonstrated that albumin and platelet levels were probably the influential factors in the prognosis of gastric precancerous lesions after ESD. As indicated in the summary of patients’ baseline characteristics (Table 1), albumin and platelet levels differed substantially between the recurrence and recurrence-free groups. Specifically, low levels of platelets and albumin may increase the recurrence rate.

ESD was introduced primarily to promote en bloc resection of early gastrointestinal tumors, and has become more and more popular in Asia and the rest of the world [8]. Some studies have suggested that ESD can be considered a standard treatment for early gastric cancer, as it is associated with low incidences of lymph node metastasis and local recurrence [9,10,11,12,13]. A retrospective study of a large population indicated that the cumulative incidences of early gastric cancer after ESD treatment were 9.5%, 13.1% and 22.7% after 5, 7 and 10 years, respectively [14]. Platelet counts, lymph node metastasis, etc. may be prognostic factors for early gastric cancer, according to some previous studies [15, 16]. However, few studies have determined the factors associated with precancerous lesion recurrence after ESD. We investigated such factors in this study, and found that low platelet counts and albumin levels were associated with the recurrence of atypical hyperplasia after ESD.

Platelet counts are determined by the balance between platelet productivity and consumption. Depending on the effective compensation mechanism, normal platelet counts may mask highly hypercoagulative and proinflammatory cancer activity [17]. High platelet levels can lead to poor prognoses in various cancers, including pancreatic cancer, gastric cancer, colorectal cancer, endometrial cancer and ovarian cancer [18,19,20,21,22]. By responding to molecules that tumors produce to stimulate angiogenesis, platelets can cause thrombosis events that facilitate cancer progression [23]. However, based on the present data, we consider platelets to exert a positive effect in preventing the recurrence of gastric mucosal atypical hyperplasia.

Platelets may influence the prognosis of patients through some of their functions. Platelets are anucleate blood cells that break off from megakaryocytes in human bone marrow. They are greatly versatile effectors of hemostasis, immune activity and inflammation, and are involved in host defense, immune surveillance and response to injury. More than 300 proteins and lipids can be secreted or translocated to the plasma membrane by activated platelets. Platelet factor 4, a member of the CXC chemokine family, can promote monocyte differentiation to macrophages [24], which is essential for the innate immune response against H. pylori [25]. Various types of gastric mucosal cell injury can cause the formation of gastric precancerous lesions [26]. In the chronic process of gastric ulcer, as a form of mucosal injury, its edge can evolve into atypical hyperplasia [27]. Therefore helping the healing of gastric ulcer can reduce the incidence of atypical hyperplasia. One study reported that macrophages were helpful in the healing of gastric ulcers by promoting angiogenesis via upregulation of cyclooxygenase-2/prostaglandin E2 production [28]. On the other hand, platelets could release vascular endothelial growth factor to accelerate healing of gastric ulcers [29]. Nitric oxide (NO) and its derivatives such as OH− and NO2− could cause DNA damage and tissue injury leading to the formation of atypical hyperplasia or even cancer [30, 31]. Platelet-derived growth factor can inhibit macrophage production of nitric oxide to reduce cellular injury [32]. Thus, platelet-related mechanisms may have appealing effects on the outcome of gastric mucosal atypical hyperplasia.

Nutritional imbalances are among the causes of many diseases, and the serum albumin level is an indicator of an individual’s nutritional status. Hypoalbuminemia can cause delayed wound healing. Furthermore, there is a complex interaction between atypical hyperplasia and inflammation [33]. Serum albumin levels are associated with systemic inflammatory conditions; for instance, inflammatory factors such as IL-6 and IL-4 can affect the synthesis of albumin by hepatocytes and reduce serum albumin levels [34]. Therefore, low serum albumin levels may be associated with a poor prognosis in the present study.

From the above study, we hope to suggest better follow-up for patients after ESD, for example, closer follow-up of patients with relatively low platelets and relatively low albumin to detect their poor prognosis earlier.

There are some limitations to our research. This was a retrospective study with inevitable selection bias. In addition, the mechanism responsible for low platelet and albumin levels in patients with recurrent gastric mucosal atypical hyperplasia requires further exploration and clarification. In conclusion, our study revealed that low platelet and albumin levels were probably unfavorable prognostic factors in intraepithelial neoplasia of the stomach after ESD. Because of the small sample size included in our study, this may make the conclusions less evidential in strength. We will therefore collect a larger sample in the future to refine the study. The exact mechanism whereby low platelet and albumin levels are associated with precancerous lesions of gastric cancer will also be investigated in future studies.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

de Vries AC, van Grieken NC, Looman CW, et al. Gastric cancer risk in patients with premalignant gastric lesions: a nationwide cohort study in the Netherlands. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(4):945–52.

Rugge M, Cassaro M, Di Mario F, et al. The long term outcome of gastric non-invasive neoplasia. Gut. 2003;52(8):1111–6.

Ono H, Yao K, Fujishiro M, et al. Guidelines for endoscopic submucosal dissection and endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer (second edition). Digest Endosc. 2021;33(1):4–20.

Hu J, Zhao Y, Ren M, et al. The comparison between endoscopic submucosal dissection and surgery in gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2018;2018:4378945.

Liu Q, Ding L, Qiu X, et al. Updated evaluation of endoscopic submucosal dissection versus surgery for early gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2020;73:28–41.

Iwai N, Dohi O, Naito Y, et al. High-risk comorbidity influences prognosis in early gastric cancer after noncurative endoscopic submucosal dissection: a retrospective study. Dig Dis. 2021;39(2):96–105.

You WC, Zhang L, Gail MH, et al. Gastric dysplasia and gastric cancer: Helicobacter pylori, serum vitamin C, and other risk factors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(19):1607–12.

Nishizawa T, Yahagi N. Long-term outcomes of using endoscopic submucosal dissection to treat early gastric cancer. J Chest Surg. 2018;12(2):119–24.

Hatta W, Gotoda T, Koike T, et al. A recent argument for the use of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancers. Gut Liver. 2020;14(4):412–22.

Ahn JY, Kim YI, Shin WG, et al. Comparison between endoscopic submucosal resection and surgery for the curative resection of undifferentiated-type early gastric cancer within expanded indications: a nationwide multi-center study. Gastr Cancer. 2021;24(3):731–43.

Kosaka T, Endo M, Toya Y, et al. Long-term outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: a single-center retrospective study. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:183–91.

Tanabe S, Ishido K, Higuchi K, et al. Long-term outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: a retrospective comparison with conventional endoscopic resection in a single center. Gastr Cancer. 2014;17:130–6.

Oda I, Oyama T, Abe S, et al. Preliminary results of multicenter questionnaire study on long-term outcomes of curative endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:214–9.

Abe S, Oda I, Suzuki H, et al. Long-term surveillance and treatment outcomes of metachronous gastric cancer occurring after curative endoscopic submucosal dissection. Endoscopy. 2015;47:1113–8.

Mezouar S, Frere C, Darbousset R, et al. Role of platelets in cancer and cancer-associated thrombosis: experimental and clinical evidences. Thromb Res. 2016;139:65–76.

Otsuji E, Kuriu Y, Ichikawa D, et al. Prediction of lymph node metastasis by size of early gastric carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54(74):602–5.

Seretis C, Youssef H, Chapman M. Hypercoagulation in colorectal cancer: what can platelet indices tell us. Platelets. 2015;26:114–8.

Mantini G, Meijer LL, Glogovitis I, et al. Omics analysis of educated platelets in cancer and benign disease of the pancreas. Cancers. 2021;13(1):66.

Wang J, Li J, Wei S, et al. The ratio of platelets to lymphocytes predicts the prognosis of metastatic colorectal cancer: a review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2021;2021:9699499.

Saito R, Shoda K, Maruyama S, et al. Platelets enhance malignant behaviours of gastric cancer cells via direct contacts. Br J Cancer. 2021;124(3):570–3.

Muzykiewicz K, Iwanska E, Janeczek M, et al. The analysis of the prognostic value of the neutrophil/ lymphocyte ratio and the platelet/lymphocyte ratio among advanced endometrial cancer patients. Ginekol Pol. 2021;92(1):16–23.

Chon S, Lee S, Jeong D, et al. Elevated platelet lymphocyte ratio is a poor prognostic factor in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2021;50(6):101849.

Jurasz P, Alonso-Escolano D, Radomski MW, et al. Platelet–cancer interactions: mechanisms and pharmacology of tumour cell-induced platelet aggregation. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;143:819–26.

Vieira-de-Abreu A, Campbell RA, Weyrich AS, et al. Platelets: versatile effector cells in hemostasis, inflammation, and the immune continuum. Semin Immunopathol. 2012;34:5–30.

Pathak SK, Tavares R, de Klerk N, et al. Helicobacter pylori protein JHP0290 binds to multiple cell types and induces macrophage apoptosis via tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-dependent and independent pathways. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e77872.

Correa P, Haenszel W, Cuello C, et al. Gastric precancerous process in a high risk population: cross sectional studies. Cancer Res. 1990;50:4731–6.

Morson BC, Sobin LH, Grundmann E, et al. Precancerous conditions and epithelial dysplasia in the stomach. J Clin Pathol. 1980;33:711–21.

Kawahara Y, Nakase Y, Isomoto Y, et al. role of macrophage colony-stimulating factor (m-csf)-dependent macrophages in gastric ulcer healing in mice. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2011;62(4):441–8.

Wallace JL, Dicay M, McKnight W, et al. Platelets accelerate gastric ulcer healing through presentation of vascular endothelial growth factor. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;148:274–8.

Ohshima H, Bartsch H. Chronic infections and inflammatory processes as cancer risk factors: possible role of nitric oxide in carcinogenesis. Mutat Res/Fundam Mol Mech Mutagen. 1994;305:253–64.

Nardone G, Rocco A, Malfertheiner P. Helicobacter pylori and molecular events in precancerous gastric lesions. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:261–70.

Pfeilschifter J, Kunz D, Mühl H. Nitric oxide: an inflammatory mediator of glomerular mesangial cells. Nephron. 1993;64:518–25.

Chen Z, Wu J, Xu D, et al. Epidermal growth factor and prostaglandin E2 levels in Helicobacter pylori-positive gastric intraepithelial neoplasia. J Int Med Res. 2016;44:241–7.

Li Y, Liu FY, Liu ZH, et al. Effect of tacrolimus and cyclosporine A on suppression of albumin secretion induced by inflammatory cytokines in cultured human hepatocytes. Inflamm Res. 2006;55(5):216–20.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge Professor, jianfang li, for his guidance during this research.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The idea for the article was conceived by GL. The manuscript was drafted by YH. Statistical analyses were performed by XC. The manuscript was critically reviewed by GL and YH. All authors reviewed the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by institutional Review Board of The First People’s Hospital of Xiaoshan District. The need for informed consent was waived by the ethics committee/Institutional Review Board of The First People’s Hospital of Xiaoshan District, because of the retrospective nature of the study. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations (Declaration of Helsinki).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hong, Y., Chen, X. & Li, G. Prognostic factors in the treatment of gastric mucosal atypical hyperplasia by endoscopic submucosal dissection. BMC Surg 22, 382 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-022-01832-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-022-01832-4