Abstract

Background

The Shoulder and Pain Disability Index (SPADI) is a widely used outcome measure. The aim of this study is to explore the reliability and validity of SPADI in a sample of patients with idiopathic frozen shoulder.

Methods

The SPADI was administered to 124 patients with idiopathic frozen shoulder. A sub-group of 29 patients were retested after 7 days. SPADI scores were correlated with other outcome measures (i.e., Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand Questionnaire – DASH; Numerical Pain Rating Scale—NPRS; and 36-item Short Form Health Survey—SF-36) to examine construct validity. Structural validity was assessed by a Two-Factors Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). Internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and measurement error were also analyzed.

Results

The construct validity was satisfactory as seven out of eight of the expected correlations formulated (≥ 75%) for the subscales were satisfied. The CFA showed good values of all indicators for both Pain and Disability subscales (Comparative Fit Index = 0.999; Tucker-Lewis Index = 0.997; Root Mean Square Error of Approximation = 0.030). Internal consistency was good for pain (α = 0.859) and disability (α = 0.895) subscales. High test–retest reliability (Intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC]) was found for pain (ICC = 0.989 [95% Confidence Interval (CI = 0.975–0.995]) and disability (ICC = 0.990 [95% CI = 0.988–0.998]). Standard Error of Measurement values of 2.27 and 2.32 and Minimal Detectable Change values of 6.27 and 6.25 were calculated for pain and disability subscales, respectively.

Conclusion

The SPADI demonstrated satisfactory reliability and validity properties in a sample of patients with idiopathic frozen shoulder.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Idiopathic Frozen Shoulder (FS) is often characterized by severe shoulder pain and functional restrictions of both active and passive shoulder motion [1]. These restrictions are usually unremarkable in radiographs of the glenohumeral joint, and there is no gold standard diagnostic test for this syndrome [2]. Based on the clinical findings, an appropriate diagnostic process should include: limitations of both active and passive Range of Motion (ROM) in different planes of movement, especially in external rotation at varying degrees of shoulder abduction [3], and a normal shoulder radiograph in order to exclude/eliminate any additional pathologies that may exist [4].

Delays in the clinical diagnostic process incomplete or unclear prognostic information, and lack of a standard rehabilitation program are issues that may increase the patients’ frustration and the socio-cultural impact that FS has on their life [5]. FS generally impacts multiple aspects of daily life, from leisure time to work: everything is modified to adapt to the related disabilities [6].

In order to achieve an effective therapeutic alliance, it is essential to use clear and valid information that is based on the best available evidence. This will allow a tailored rehabilitation program to be developed based on the patient's needs and fears. In this context, health indicators could be used to overcome the discrepancy between clinicians’ and patients' perceptions [7] of disabling conditions. To this extent, the Patient Reported Outcome Measures system (PROMs) [8], which measures patients’ perceptions of their health status, clinical outcomes, mobility, and quality of life [9], can systematically assess the patients’ point of view, leading to improved communication and patient management using a personalized care approach [10].

Based on our literature review, only one study has assessed the responsiveness of the Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI) in a sample of patients with FS, which demonstrated that it could be an appropriate PROMs to assess the point of view of this population [11]. This self-administered index consists of 13 items divided into two subscales: 5 items for pain and 8 items for disability [7], which are also the two aspects that most concern patients with FS [9]. The SPADI is a practical outcome measure that can be completed by patients in less than 5 min and is easily scored by clinicians [12]. SPADI has been shown to have excellent reliability and construct validity in the assessment of shoulder impairments [13], mostly in patients presenting at the primary care level with shoulder pain [14, 15]. Moreover, SPADI is one of the most commonly used PROMs to assess pain and disability in patients with FS [16], even though it has not undergone any specific scientific validation in populations with FS. Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine the reliability and validity of SPADI in a sample of Italian patients with FS.

Methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients were recruited through convenience sampling in two Italian private physical therapy clinics, over a 3-year period between 2019 and 2021 if they met the following inclusion criteria: 1) over 18 years of age; 2) clinical diagnosis of idiopathic FS by orthopedic surgeons and physiotherapists based on the following findings: a) gradual and progressive onset of shoulder pain; b) a restriction of both glenohumeral active and passive ROM in multiple planes; c) sleep-disturbing night pain and/ or firm end-feel at the end ranges of movements, especially in external rotation at variable degrees of shoulder abduction that occurs for at least 1 month [3]; and 3) normal shoulder radiograph [4]. Patients were excluded if they presented with red flags (e.g., neoplasia, fractures or glenohumeral dislocation) [17], secondary stiff shoulder (following the ISAKOS 2015 classification) [2], history of trauma [2], positive history of cognitive impairments, or inability to understand the Italian language.

All procedures involving human participants were in accordance with the Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. Personal information and informed consent were obtained from all patients to participate in this study.

Outcome measures

Shoulder and Pain Disability Index (SPADI)

The Italian version of the SPADI used in this study was cross-culturally adapted and validated by Marchese C, et al., available elsewhere [18]. The SPADI has already been used to assess shoulder dysfunction in patients with neck cancer [18], in patients after shoulder surgery for anterior instability [19], and in patients with non-specific shoulder pain [20].

Before the compilation process, patients were instructed to place a mark on the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) for each of the 13 items [18]. The results of each subscale were added up and converted into a score out of 100: the closer the score is to 100, the greater the pain and disability [18]. Patients could only mark one item in each subscale as “not applicable” and, in this case, the item was omitted from the total score. If a patient marked more than two items as “non-applicable”, no score was calculated [21]. Previous studies have reported an MDC of 17 points using the SPADI in patients with FS [11] and an MDC of 18 points using the German SPADI in patients post shoulder arthroplasty [21].

Disability of Arm, Shoulder and Hand Questionnaire (DASH)

The DASH is an outcome measure that assesses the ability of an upper extremity to perform activities of daily living regardless of the site(s) and nature of musculoskeletal pathology [22]. The DASH questionnaire is composed of 30 items assessing disability and symptoms. Items on the DASH test the degree of difficulty in performing various physical, social, and work-related daily activities together with the impact on the sleep routine and the patient’s perception of him/considering the upper extremity problems [23]. For each question, patients rate their difficulty on a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘‘no difficulty or no symptoms’’ (scores 1) to ‘‘unable to perform activity or severe symptoms’’ (scores 5) [24]. The DASH score ranges from 0 (no disability) to 100 (severest disability) and cannot be calculated if there are more than 3 missing items [23]. In this study, the cross culturally adapted and validated Italian version was used [25].

Numerical Pain Rating Scale (NPRS)

The NPRS is an eleven-point measure of pain: the patient rates pain from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst imaginable pain) [26]. The NPRS has shown good responsiveness in shoulder pain [27, 28] and, in this study, it was used to assess the patient's pain perception in the previous last week.

36-Item Short Form Health Survey questionnaire (SF-36)

The SF-36 is a tool that assesses Health-Related Quality of Life [29]. The SF-36 measures eight domains: Physical Functioning (PF), Role Physical (RP), Bodily Pain (BP), General Health (GH), Vitality (VT), Social Functioning (SF), Role Emotional (RE), and Mental Health (MH) [30]. The SF- 36 has shown good properties in assessing patients with different shoulder disorders [31]. The validated Italian version was used in this study [32].

Procedures

The SPADI was administered to each patient together with the DASH, NPRS, and SF-36. Clinical and demographic data were also acquired during the recruitment phase (i.e., age, gender) through an interview conducted by a physiotherapist. Each questionnaire was self-reported by the patients.

Statistical analysis

This study has followed the definitions and procedures proposed by the COSMIN initiative [33] in the process of evaluating the psychometric properties of SPADI.

Structural validity was assessed by a two-factors Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) [34] using the following three indicators [35]: 1) Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) ≥ 0.95, 2) Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) ≤ 0.06, and 3) Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) ≤ 0.08.

Reliability was assessed as internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and measurement error. These analyses were performed on both subscales (Pain and Disability) separately. Internal consistency was evaluated according to these criteria: 1) Cronbach’s Alpha (α) [36], where values are recommended between 0.70 and 0.95. [37], 2) α if an item was deleted, where the alpha was calculated after removing each item in turn; values below the total Cronbach’s alpha are expected [38], and 3) items to total correlation, which are the nonparametric correlations (based on Spearman’s ϱ) between each item and its rest score (i.e. the total score minus the item score); values ≥ 0.40 were considered satisfactory [39].

To examine test–retest reliability, the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC2,1) with 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) [40] was calculated. The minimal ICC value required for a reliable measure of groups is > 0.75 [41], but values > 0.90 are considered essential to achieve excellent reliability in a clinical measurement at the individual level [42]. The Standard Error of Measurement (SEM) and the Minimum Detectable Change (MDC) were used to test the measurement error [43]. The SEM was calculated with the following formula: SD*√(1–ICC), where SD is the pooled standard deviation of the measurements, and the ICC value is the test–retest reliability. The MDC was calculated by multiplying the SEM by 1.96, which is the z-score associated with the 95% confidence level and the square root of 2.

The outcome measures were used for a comparative analysis to study the validity of two constructs: for pain, the SPADI Pain subscale score was correlated with the NPRS; for disability, the SPADI Disability subscale score was correlated with the DASH score even though the DASH measures disability of the upper limb and is not specific to the shoulder [44].

Construct validity was examined through an a-priori hypothesis test using the magnitudes of the Spearman’s rank correlation (rs) coefficients between the SPADI and the other three scales (DASH, NPRS, and SF-36).The cut-offs of rs > 0.60, 0.30 < rs < 0.60, and rs < 0.30 represent strong, moderate, and weak correlations, respectively [45]. Construct validity was considered satisfactory (≥ 75%), moderate (< 75%, and ≥ 50%), or low (< 50%) depending on the percentage of expected hypotheses fulfilled [46].

Based on the expected correlations, an a-priori hypotheses testing was conducted for the following assumptions:

- For the Pain subscale:

-

1.

the positive correlation between the Pain subscale and the NPRS scores is > 0.60 because they measure the same construct, and this correlation value was found in another SPADI validation study [47];

-

2.

the positive correlation between the Pain subscale and the DASH total scores is > 0.60 as found in other SPADI validation studies [48, 49];

-

3.

the negative correlation between the Pain subscale and the Physical Functioning (PF) subscale of the SF-36 is > 0.30 since shoulder pain globally compromises the physical health status [50];

-

4.

the negative correlation between the Pain subscale and the Bodily Pain (BP) subscale of the SF-36 scores is > 0.30 and < 0.60, based on their similar constructs.

- For the Disability subscale:

-

1.

the positive correlation between the Disability subscale and the DASH total scores is > 0.60, as reported in other SPADI validation studies [19, 48, 49];

-

2.

the positive correlation between the Disability subscale and the NPRS scores is between > 0.30 and < 0.60, since pain showed a moderate correlation with disability in similar patients [15, 47];

-

3.

the negative correlation between the Disability subscale and the Role Physical (RP) subscale of the SF-36 scores is > 0.30 [47, 51];

-

4.

the negative correlation between the Disability subscale and the Social Functioning (SF) subscale of the SF-36 scores is > 0.30 [47, 51].

The R-package lavaan was used to run the CFA, while the SPSS package, version 21 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL; 2004) was used for all other statistical analyses. Statistical significance was set as p < 0.05 for all analyses.

Results

Subjects

One hundred and twenty-four (mean ± SD age = 55.2 ± 7.7 years, 46.8% male) subjects with FS were included in this study. Detailed demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. A sub-group of twenty-nine patients were used to conduct the test–retest after seven days.

Structural validity

Considering the results of the CFA applied on the two SPADI subscales (Pain and Disability), good values were found for all indicators. The CFA results revealed a two-factor structure (CFI = 0.999; TLI = 0.997; RMSEA = 0.030; SRMR = 0.051).

Internal consistency

Internal consistency findings are reported in Table 2. Remarkably good internal consistency was shown for both subscales (α for pain = 0.859 and α for disability = 0.895). Similarly, good results were obtained with the analysis of the item-to-total correlations: values were > 0.40 in both Pain and in Disability subscales. Alpha did not increase (it should be < α) after deleting most of the elements in both subscales, except item #9 of the Disability subscale in accordance to Cronbach’s alpha-if-item-deleted data.

Reliability

The results on reliability are shown in Table 3. Test–retest reliability (studied on 29 subjects) showed an ICC2,1 (95% CI) of 0.989 (0.975–0.995) for the Pain subscale and 0.990 (0.988–0.998) for the Disability subscale.

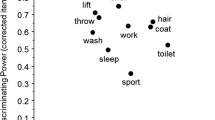

Construct Validity

The correlation coefficients of the a-priori hypotheses between SPADI subscales and the other scales administered to patients are reported in Table 4.

The construct validity for each subscale was satisfactory. Four out of four (100%) for the Pain subscale and three out of four for the Disability subscale (75%) of the a-priori hypotheses were satisfied.

Discussion

The present study suggests that SPADI can be used to assess pain and disability in patients with FS [9], given the fact that these constructs are of high concern to patients with FS [9]. Indeed, an analysis of 124 patients with idiopathic FS indicated good reliability and validity of both SPADI subscales.

Confirmatory factor analysis in our data revealed that SPADI has two dimensions (i.e., ‘‘pain’’, ‘‘disability’’). The CFA showed well-fitting values with a CFI of 0.999, a TLI of 0.997, and a low error value with an RMSEA of 0.030 and an SRMR of 0.051. The two-dimensions of the SPADI are consistent with findings from the original version of the questionnaire [7], as well as the Danish version [52], the Spanish version [47, 53], the Chinese version [51], the Greek version [54]and the other Italian version [20]. However, different findings were obtained in the Turkish [55] and Dutch [56] versions, with three factors and one-factor structures, respectively; these dissimilarities could be explained by different clinical characteristics, the shoulder pain caused by a variety of conditions (i.e. results were not specific to FS), and cultural and social factors in the patient populations studied.

The internal consistency of the SPADI was satisfactory in the Pain (α = 0.859) and Disability (α = 0.895) subscales. These values are consistent with those found in other studies including the development of the SPADI (in English) [7], a Chinese version validated on patients with shoulder pain [51], in a Spanish version validated on patients with six different shoulder disorders [47], and in similar Italian studies on patients with shoulder pain after neck dissection [18] or surgery for anterior instability [19].

The strong agreement between the internal consistency values for Pain and Disability subscales found in this study and those of the original version demonstrates the effectiveness of this questionnaire in assessing FS. Despite the internal consistency of each subscale, the α if-item-is-deleted of item #9 from the Disability subscale indicates a discordant value and reveals the redundancy of the item in relation to the consistency of the entire questionnaire [41]. This redundancy could be explained by the fact that item #9 investigates an activity (wearing a shirt that buttons at the front) that requires scapulothoracic abduction and internal rotation movements together with the humeroulnar flexion and extension movements. In patients with FS, glenohumeral internal rotation limitations are typically less debilitating since scapulothoracic movement helps the patient to compensate [3]. Moreover, to our best knowledge, in the available literature, there are no similar results regarding item #9 of the Disability subscale. On the other hand, the item with the highest value of α if-item-is-deleted is #6 (washing the hair; α = 0.902): this action fully involves shoulder abduction and external rotation and is one of the most provocative action in a patient with FS [6].

The construct validity of each subscale was remarkable, with 4/4 (100%) hypotheses satisfied for the Pain subscale and 3/4 (75%) hypotheses satisfied for the Disability subscale. The analysis of the construct validity brings to light knowledge similar to those that can be found in the literature [19, 47, 49, 51]; in fact, while the correlation hypotheses with NPRS and DASH were satisfied, those relating to SF-36 were not always satisfied and showed lower rs values. Weaker relationships between SPADI and SF-36 was also observed in another Italian validation study [20] and could be interpreted as using the SPADI alone does not adequately evaluate the impact that FS has on a patient's quality of life. The implicit limit of this index is that it is not fully capable of assessing this condition due to its purported constructs, which minimally evaluates an aspect like social function, a domain that is not necessarily reflected in shoulder disabilities. Moreover, it could be argued that the continuous activity of nociceptive impulses occurring at the first manifestations of FS could lead to peripheral and later long-lasting central sensitization, together with an altered perception of the patient's state of health [57]. However, to date the involvement of central mechanisms in FS and the efficacy of a treatment approach focused on the central nervous system are still under study [57,58,59,60,61,62]. Consequently, the two PROMs should be administered together to more comprehensively assess the patient’s experience.

The standard deviation for the pain duration presented in Table 1 is quite large; this means that patients with different symptoms have composed the sample taken. Those data support the results of this study, demonstrating the generalizability of the findings to any patient with FS, regardless of symptoms’ entities.

According to COSMIN, a necessary condition for the use of the total score in clinical practice is that the total score is unidimensional [33, 46]. Moreover, the COSMIN recommendations [33] suggest that if the measurement instrument has two (or more) factors, the psychometric properties for these two (or more) factors should be studied separately, without considering the total score. Our results show that the SPADI has two-factors: pain and disability; therefore, the psychometric properties were examined separately for these two factors and the total score (which is affected by error) was not included in the analysis. Several cases were reported in the literature in which the total score was examined, although the SPADI has been consistently shown to have two dimensions [7, 20, 51,52,53,54,55]. Therefore, in clinical practice and future research, separate scores for each of the two subscales should be used rather than the total score. The present study shows good reliability and validity values of the SPADI and validates it for the assessment of patients with FS. In addition, the main contribution of this study is that the results are the first that can be fully defined in the validation process of SPADI in the patients with FS. In fact, the only other study found by the authors that examined the same patient population [11] had a smaller sample (n = 76) and only reported test–retest reliability and responsiveness of the SPADI.

It is worth noting the following limitations of this study: the results may lack generalizability, as this study only included patients with Idiopathic FS. Therefore, the results of this study should be applied in clinical practice only to patients diagnosed with FS. Moreover, the test–retest reliability sample consisted of only 29 patients; hence, these findings should be taken with caution. Further studies should be designed to assess other psychometric properties such as responsiveness and content validity. Finally, modern psychometric analyses (i.e., Rasch analysis) were not used to further investigate psychometric properties such as structural validity.

Conclusion

In conclusion, SPADI has good internal consistency, reliability, and validity in a sample of patients with FS. Future studies should confirm responsiveness, interpretability, and content validity, as these properties have not been studied.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Abrassart S, Kolo F, Piotton S, Chih-Hao Chiu J, Stirling P, Hoffmeyer P, Lädermann A. “Frozen shoulder” is ill-defined. How can it be described better? EFORT Open Rev. 2020;5:273–9.

Itoi E, Arce G, Bain GI, Diercks RL, Guttmann D, Imhoff AB, Mazzocca AD, Sugaya H, Yoo YS. Shoulder Stiffness: Current Concepts and Concerns. Arthroscopy. 2016;32:1402–14.

Kelley MJ, Shaffer MA, Kuhn JE, Michener LA, Seitz AL, Uhl TL, Godges JJ, McClure PW. Shoulder pain and mobility deficits: adhesive capsulitis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2013;43:A1-31.

Bunker TD. Time for a new name for “frozen shoulder.” Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1985;290:1233–4.

Jones S, Hanchard N, Hamilton S, Rangan A. A qualitative study of patients’ perceptions and priorities when living with primary frozen shoulder. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003452.

Carter B. Clients’ experiences of frozen shoulder and its treatment with Bowen technique. Complement Ther Nurs Midwifery. 2002;8:204–10.

Roach KE, Budiman-Mak E, Songsiridej N, Lertratanakul Y. Development of a shoulder pain and disability index. Arthritis Care Res. 1991;4:143–9.

Coulter A. Measuring what matters to patients. BMJ. 2017;356:j816.

de Bienassis K, Kristensen S, Hewlett E, Roe D, Mainz J, Klazinga N. Measuring patient voice matters: setting the scene for patient-reported indicators. Int J Qual Health Care. 2021;34(Suppl 1):ii3–ii6. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzab002.

Brundage MD, Wu AW, Rivera YM, Snyder C. Promoting effective use of patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice: themes from a “Methods Tool kit” paper series. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;122:153–9.

Tveitå EK, Ekeberg OM, Juel NG, Bautz-Holter E. Responsiveness of the shoulder pain and disability index in patients with adhesive capsulitis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:161.

Williams JW, Holleman DR, Simel DL. Measuring shoulder function with the Shoulder Pain and Disability Index. J Rheumatol. 1995;22:727–32.

Badalamente M, Coffelt L, Elfar J, Gaston G, Hammert W, Huang J, Lattanza L, Macdermid J, Merrell G, Netscher D, et al. Measurement scales in clinical research of the upper extremity, part 2: outcome measures in studies of the hand/wrist and shoulder/elbow. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38:407–12.

MacDermid JC, Solomon P, Prkachin K. The Shoulder Pain and Disability Index demonstrates factor, construct and longitudinal validity. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7:12.

Paul A, Lewis M, Shadforth MF, Croft PR, Van Der Windt DA, Hay EM. A comparison of four shoulder-specific questionnaires in primary care. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:1293–9.

Maund E, Craig D, Suekarran S, Neilson A, Wright K, Brealey S, Dennis L, Goodchild L, Hanchard N, Rangan A, et al. Management of frozen shoulder: a systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2012;16:1–264.

Goodman C, Snyder T: Differential diagnosis for physical therapists, screening for referral. 5th ed. Edn. 2012.

Marchese C, Cristalli G, Pichi B, Manciocco V, Mercante G, Pellini R, Marchesi P, Sperduti I, Ruscito P, Spriano G. Italian cross-cultural adaptation and validation of three different scales for the evaluation of shoulder pain and dysfunction after neck dissection: University of California - Los Angeles (UCLA) Shoulder Scale, Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI) and Simple Shoulder Test (SST). Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2012;32:12–7.

Vascellari A, Venturin D, Ramponi C, Ben G, Poser A, Rossi A, Coletti N. Psychometric properties of three different scales for subjective evaluation of shoulder pain and dysfunction in Italian patients after shoulder surgery for anterior instability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018;27:1497–504.

Brindisino F, Indaco T, Giovannico G, Ristori D, Maistrello L, Turolla A. Shoulder Pain and Disability Index: Italian cross-cultural validation in patients with non-specific shoulder pain. Shoulder Elbow. 2021;13:433–44.

Angst F, Goldhahn J, Pap G, Mannion AF, Roach KE, Siebertz D, Drerup S, Schwyzer HK, Simmen BR. Cross-cultural adaptation, reliability and validity of the German Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI). Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46:87–92.

Hudak PL, Amadio PC, Bombardier C. Development of an upper extremity outcome measure: the DASH (disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand) [corrected]. The Upper Extremity Collaborative Group (UECG). Am J Ind Med. 1996;29:602–8.

Tongprasert S, Rapipong J, Buntragulpoontawee M. The cross-cultural adaptation of the DASH questionnaire in Thai (DASH-TH). J Hand Ther. 2014;27:49–54.

Dixon D, Johnston M, McQueen M, Court-Brown C. The Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand Questionnaire (DASH) can measure the impairment, activity limitations and participation restriction constructs from the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:114.

Padua R, Padua L, Ceccarelli E, Romanini E, Zanoli G, Amadio PC, Campi A. Italian version of the Disability of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) questionnaire. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation. J Hand Surg Br. 2003;28:179–86.

Katz J, Melzack R. Measurement of pain. Surg Clin North Am. 1999;79:231–52.

Mintken PE, Glynn P, Cleland JA. Psychometric properties of the shortened disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand Questionnaire (QuickDASH) and Numeric Pain Rating Scale in patients with shoulder pain. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18:920–6.

Michener LA, Snyder AR, Leggin BG. Responsiveness of the numeric pain rating scale in patients with shoulder pain and the effect of surgical status. J Sport Rehabil. 2011;20:115–28.

Lyons RA, Perry HM, Littlepage BN. Evidence for the validity of the Short-form 36 Questionnaire (SF-36) in an elderly population. Age Ageing. 1994;23:182–4.

Lins L, Carvalho FM. SF-36 total score as a single measure of health-related quality of life: Scoping review. SAGE Open Med. 2016;4:2050312116671725.

Smith KL, Harryman DT, Antoniou J, Campbell B, Sidles JA, Matsen FA. A prospective, multipractice study of shoulder function and health status in patients with documented rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9:395–402.

Apolone G, Mosconi P. The Italian SF-36 Health Survey: translation, validation and norming. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1025–36.

Mokkink LB, Prinsen CA, Bouter LM, Vet HC, Terwee CB. The COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) and how to select an outcome measurement instrument. Braz J Phys Ther. 2016;20:105–13.

Long J. Confirmatory factor analysis: a preface to LISREL. Sage Pubblications edition. Beverly Hills: Sage Pubblications; 1983.

La Porta F, Franceschini M, Caselli S, Cavallini P, Susassi S, Tennant A. Unified Balance Scale: an activity-based, bed to community, and aetiology-independent measure of balance calibrated with Rasch analysis. J Rehabil Med. 2011;43:435–44.

Bland JM, Altman DG. Cronbach’s alpha. BMJ. 1997;314:572.

Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, van der Windt DA, Knol DL, Dekker J, Bouter LM, de Vet HC. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:34–42.

Yusoff MSB, Rahim AFA, Yaacob MJ. The development and validity of the Medical Student Stressor Questionnaire (MSSQ). ASEAN JPsychiatry. 2010;11(1):231–5.

Clark LA, Watson D. Constructing validity: New developments in creating objective measuring instruments. Psychol Assess. 2019;31:1412–27.

Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86:420–8.

Post MW. What to Do With “Moderate” Reliability and Validity Coefficients? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97:1051–2.

Portney L: Foundations of Clinical Research: Applications to Practice (Vol. 2). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2000.

Weir JP. Quantifying test-retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient and the SEM. J Strength Cond Res. 2005Feb;19(1):231–40. https://doi.org/10.1519/15184.1.

Angst F, Schwyzer HK, Aeschlimann A, Simmen BR, Goldhahn J. Measures of adult shoulder function: Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand Questionnaire (DASH) and its short version (QuickDASH), Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI), American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) Society standardized shoulder assessment form, Constant (Murley) Score (CS), Simple Shoulder Test (SST), Oxford Shoulder Score (OSS), Shoulder Disability Questionnaire (SDQ), and Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index (WOSI). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63(Suppl 11):S174-188.

Chiarotto A, Vanti C, Ostelo RW, Ferrari S, Tedesco G, Rocca B, Pillastrini P, Monticone M. The Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire: Cross-Cultural Adaptation into Italian and Assessment of Its Measurement Properties. Pain Pract. 2015;15:738–47.

Prinsen CA, Vohra S, Rose MR, Boers M, Tugwell P, Clarke M, Williamson PR, Terwee CB. How to select outcome measurement instruments for outcomes included in a “Core Outcome Set” - a practical guideline. Trials. 2016;17:449.

Membrilla-Mesa MD, Cuesta-Vargas AI, Pozuelo-Calvo R, Tejero-Fernández V, Martín-Martín L, Arroyo-Morales M. Shoulder pain and disability index: cross cultural validation and evaluation of psychometric properties of the Spanish version. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:200.

Brealey S, Northgraves M, Kottam L, Keding A, Corbacho B, Goodchild L, Srikesavan C, Rex S, Charalambous CP, Hanchard N, et al. Surgical treatments compared with early structured physiotherapy in secondary care for adults with primary frozen shoulder: the UK FROST three-arm RCT. Health Technol Assess. 2020;24:1–162.

Phongamwong C, Choosakde A. Reliability and validity of the Thai version of the Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (Thai SPADI). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:136.

Byrne B: Structural equation modeling with AMOS: basic concepts,applications, and programming. 2nd ed. edn. New York: Routledge; 2010.

Yao M, Yang L, Cao ZY, Cheng SD, Tian SL, Sun YL, Wang J, Xu BP, Hu XC, Wang YJ, et al. Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI) into Chinese. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;36:1419–26.

Christiansen DH, Andersen JH, Haahr JP. Cross-cultural adaption and measurement properties of the Danish version of the Shoulder Pain and Disability Index. Clin Rehabil. 2013;27:355–60.

Luque-Suarez A, Rondon-Ramos A, Fernandez-Sanchez M, Roach KE, Morales-Asencio JM. Spanish version of SPADI (shoulder pain and disability index) in musculoskeletal shoulder pain: a new 10-items version after confirmatory factor analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14:32.

Vrouva S, Batistaki C, Koutsioumpa E, Kostopoulos D, Stamoulis E, Kostopanagiotou G. The Greek version of Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI): translation, cultural adaptation, and validation in patients with rotator cuff tear. J Orthop Traumatol. 2016;17:315–26.

Bumin G, Tüzün EH, Tonga E. The Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI): Cross-cultural adaptation, reliability, and validity of the Turkish version. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabilitation. 2008;21:57–62.

Thoomes-de Graaf M, Scholten-Peeters GG, Duijn E, Karel Y, Koes BW, Verhagen AP. The Dutch Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI): a reliability and validation study. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:1515–9.

Lluch-Girbés E, Dueñas L, Mena-Del Horno S, Luque-Suarez A, Navarro-Ledesma S, Louw A. A central nervous system-focused treatment approach for people with frozen shoulder: protocol for a randomized clinical trial. Trials. 2019;20:498.

Struyf F, Meeus M. Current evidence on physical therapy in patients with adhesive capsulitis: what are we missing? Clin Rheumatol. 2014;33:593–600.

Breckenridge JD, McAuley JH, Ginn KA. Motor Imagery Performance and Tactile SpatialAcuity: Are They Altered in People with Frozen Shoulder? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(20):7464. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207464.

Mena-Del Horno S, Balasch-Bernat M, Dueñas L, Reis F, Louw A, Lluch E. Laterality judgement and tactile acuity in patients with frozen shoulder: A cross-sectional study. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2020;47:102136.

Sawyer EE, McDevitt AW, Louw A, Puentedura EJ, Mintken PE. Use of Pain Neuroscience Education, Tactile Discrimination, and Graded Motor Imagery in an Individual With Frozen Shoulder. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2018;48:174–84.

Louw A, Puentedura EJ, Reese D, Parker P, Miller T, Mintken PE. Immediate Effects of Mirror Therapy in Patients With Shoulder Pain and Decreased Range of Motion. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98:1941–7.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Physical Therapists who contributed and collected data for the study and the patients who generously gave their time and participated in the study. Moreover, the authors thank Sanaz Pournajaf for the linguistic revision and Kevin Chui (Radford University) for the linguistic revision and consultation.

Funding

This project was partially funded by the Italian Ministry of Health (ricerca corrente).

Ministero della Salute,ricerca corrente

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: DV, AP; Data Curation: DV, GG; Formal analysis: LP, MG; Data collection: DV, AR, DP, AP; Writing – Original Drat: DV, GG, All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures involving human participants were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. Written informed consent was obtained from all of the patients to participate the study. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Local health company of Lecce (Italy) (protocol number 20, June 4th, 2018).

Consent for publication

Not appropriate.

Competing interests

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Venturin, D., Giannotta, G., Pellicciari, L. et al. Reliability and validity of the Shoulder Pain and Disability Index in a sample of patients with frozen shoulder. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 24, 212 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-023-06268-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-023-06268-2