Abstract

Background

The Asthma Control Test (ACT) has been used to assess asthma control in both clinical trials and clinical practice. However, the relationships between ACT score and other measures of asthma impact are not fully understood. Here, we evaluate how ACT scores relate to other clinical, patient-reported, or economic asthma outcomes.

Methods

A targeted literature search of online databases and conference abstracts was performed. Data were extracted from articles reporting ACT score alongside one or more of: Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ) score; rescue medication use; exacerbations; lung function; health−/asthma-related quality of life (QoL); sleep quality; work and productivity; and healthcare resource use (HRU) and costs.

Results

A total of 1653 publications were identified, 74 of which were included in the final analysis. Of these, 69 studies found that improvement in ACT score was related to improvement in outcome(s), either as correlation or by association. The level of evidence for each relationship differed widely between outcomes: substantial evidence was identified for relationships between ACT score and ACQ score, lung function, and asthma-related QoL; moderate evidence was obtained for relationships between ACT score and rescue medication use, exacerbations, sleep quality, and work and productivity; limited evidence was identified for relationships between ACT score and general health-related QoL, HRU, and healthcare costs.

Conclusions

Findings of this review suggest that the ACT is an appropriate measure for overall asthma impact and support its use in clinical trial settings.

GlaxoSmithKline plc. study number HO-17-18170.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Asthma is a common and treatable disease that can impact heavily on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [1]. Medical experts agree that the level of asthma control is a key feature when determining the best asthma treatment required [1, 2]. Developed by asthma experts, the Asthma Control Test (ACT) provides a numerical score to assess the control of asthma [3]. It comprises five questions regarding aspects of asthma control relevant to patients. The ACT assesses frequency of shortness of breath, night-time/early awakenings, rescue medication use, overall asthma control, and loss of productivity. Each question is answered on a 5-point scale, with a total score ranging from 5 to 25; higher scores indicate improved asthma control [2, 3]. A score of ≥ 20 indicates “well-controlled” asthma, while a score < 20 indicates asthma that is “not well controlled”. The ACT provides patients with asthma and their doctors and nurses with a useful measure to help determine the level of treatment required [2, 3]. It has been tested extensively in patients with asthma [4], clinically validated against spirometry and specialist assessment [3], and is recognized by the National Institutes of Health since its 2007 asthma guidelines [2]. Despite its clinical utility, a need remains to assess the link between ACT score and asthma treatment benefits and outcomes, and its suitability as an endpoint in clinical trials. Previous studies have used the ACT as a measure of response to treatment [5, 6], including a recent Phase III study that was not published in time to be included in this review [7]. The aim of the current study was to assess the extent to which ACT score is correlated, or associated, with other important clinical, patient-reported, and economic asthma outcomes.

Methods

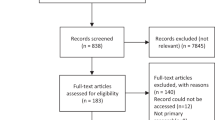

A targeted literature search of the EMBASE, MEDLINE, EconLit, and Cochrane databases was performed, in addition to searching the relevant conference abstract repositories of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), European Respiratory Society (ERS), and American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST). Articles published before February 9th, 2017 were captured in the EMBASE, MEDLINE and EconLit database searches, while searches of the Cochrane database and conference repositories reviewed articles and congress abstracts published prior to January 21st, 2017. The details of the search strategy are included in Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of search strategy and targeted literature review approach. aArticles published before February 9th, 2017 were captured in the EMBASE, MEDLINE and EconLit database searches. bThe Cochrane database search reviewed articles published prior to January 21st, 2017. cConference abstract repositories searched were the American Thoracic Society (ATS), European Respiratory Society (ERS) and American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) CHEST. dConference databases were searched for the last three editions of the conference in question (i.e. 2015–2017 or 2014–2016), up to January 21st, 2017. eStudies could have reported on multiple outcomes. ACT: Asthma Control Test; HRQoL: health-related quality of life; QoL: quality of life

Identified publications were initially screened for eligibility by title and abstract, and full-text articles of all eligible studies were then assessed. Eligible studies included human studies investigating adult patients (≥ 18 years old) with a primary asthma diagnosis. Articles reporting the results of observational studies, clinical trials, longitudinal/cross-sectional studies and other studies reporting relationships between ACT score and other outcomes of interest were included, while letters, editorials, notes, and review articles were excluded.

Articles that met predefined inclusion criteria were retained for full text review i.e. articles were included if they reported the results of studies investigating a relationship between ACT score and/or asthma severity and one or more of identified outcomes of interest: symptom control, use of rescue medication, exacerbations, pulmonary function, HRQoL/utilities, sleep quality, productivity and activity levels, and resource use and costs.

Following identification of articles eligible for full-text review, the number of articles assessing each relationship, as well as the strength, significance, and direction of those relationships, was quantified. We also evaluated the extent to which the tested relationships differed per ACT score and/or asthma severity.

Articles describing a statistical relationship between two continuous variables were defined as reporting a “correlation”; statistical tests used in these studies included Pearson’s chi-square test and the Spearman correlation test. Those that instead reported a trend between subgroups or over time, assessed by covariance tests, regression analysis, or empirical observation, were defined as reporting “associations”; in other words, these are assessments of the extent to which two measures co-vary in an expected manner (i.e. an improvement of one measure should represent an improvement in another outcome measure).

Data for each outcome of interest were extracted from the targeted studies by means of a formalized extraction grid. Bibliographic and methodologic details of the study, basic population characteristics, and ACT scores at baseline and later if applicable were extracted. For each outcome of interest that was examined for a relationship with ACT score, the following were included: a description of the outcome and its value; time of measurement (baseline/later); change from baseline; method used to test relationship and the outcome of the test; significance level (range, 95% confidence interval, or p-value); statistical significance of relationship (yes/no); and the direction of the relationship (positive/negative).

Data availability

All publications identified in the targeted literature review were available from public databases (EMBASE, MEDLINE, EconLit, and the Cochrane Library), and can be accessed there or on the articles’ respective journal websites. Conference abstracts were available from the abstract repositories of the professional organizations that arranged the conferences in question (the ATS, ERS, and CHEST). Relevant data were extracted from these publications, but no new data were generated within the course of this literature review. Accordingly, no databases or data repositories were created. The protocol for this literature review is not publicly available.

Results

The targeted literature search identified 1653 publications (1401 in EMBASE, MEDLINE, and EconLit; 116 in Cochrane databases; and 136 in conference abstracts), of which 67 were duplicates. Of the 1586 unduplicated publications screened, 239 were reviewed in full and 74 were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1). The analysis found that in 68 publications an improvement in ACT score was correlated or associated with improvements in key outcomes of interest (Table 1). Studies assessing symptom control, healthcare resource use, or lung function were among the most commonly identified; fewer studies assessing QoL, sleep, and productivity were found. Asthma severity was not frequently reported.

ACT score and asthma symptom control

In total, seven publications reported ACT and Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ) data (Table 1) [8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. Six publications found strong and consistent correlations between improvement in ACT score and improvement in ACQ score [8,9,10,11,12,13], with five of the publications assessing the statistical significance of the correlations. All five of these reports found statistically significant relationships between ACT and ACQ scores (p < 0.05) [8,9,10,11,12]. Schuler et al. [12] reported that the ACQ-7 had a strong positive correlation, with a moderate correspondence with ACT score (Cohen’s kappa κ = 0.56). Zhou et al. [13] reported strong correlations between improvement in ACT score and improvement in both the ACQ-7 (all items) (Spearman correlation coefficient, r = − 0.687; robust correlation, r = − 0.865) and the ACQ-6 (excluding spirometry; Spearman correlation coefficient, r = − 0.491; robust correlation, r = − 0.637), although statistical significance was not tested. A further publication reported a similarly moderate effect with the same measure of concordance (κ = 0.52) as Schuler et al., without testing for significance [14].

ACT score and rescue medication use

Almost all of the 10 publications reporting on ACT score and rescue medication use [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24] found a relationship between worsening ACT scores and increasing short-acting beta agonist (SABA) or rescue inhaler use (Table 1). Weak but statistically significant correlations between ACT score and the number of SABA inhalers dispensed were identified in two publications (ρ = − 0.33, p = 0.001 in both); these studies may have been reporting on the same population [15, 16]. One study reported strong relationships between risk of excess SABA use and both ACT score and change in ACT score; a 2-point worsening in ACT score led to a 46% increased risk of excess SABA use [22]. Another publication showed that the odds of having ≥6 SABA inhaler dispensings increased markedly at lower ACT scores over a continuous range of ACT scores [23].

Three publications reported SABA use by asthma control subgroup, and demonstrated trends between lower ACT score and higher rescue inhaler use [18, 20, 24], with one study performing a regression analysis (r = 0.51, p < 0.001) [18].

Only one study was identified that evaluated the relationship between ACT score and rescue medication-free days. Improvement was evaluated by both a change from baseline and the proportion of patients who achieved asthma control, similar to the Salford Lung Study trial design [25]. The results suggested that improvement in ACT score was related to improvement in rescue medication-free days [19].

ACT score and asthma exacerbations

Ten studies reported on the relationship between improvement in ACT score and reduction in asthma exacerbations (Table 1) [17, 22, 23, 26,27,28,29,30,31,32].

Across the studies, there was some variation in the definitions used to characterize an exacerbation. However, these definitions were generally comparable, specifying an exacerbation as a worsening in asthma symptoms that required one or more of oral/systemic corticosteroid use, hospitalization, or an emergency healthcare visit.

Two of the studies tested for correlations between improvement in ACT score and reduction in asthma exacerbations, resulting in small but significant correlation coefficients of − 0.129 and − 0.349, respectively (p < 0.01) [26, 27].

In the other eight publications, fewer exacerbations were observed in patients with higher ACT scores [17, 22, 23, 28,29,30,31,32], with seven of these publications reporting a statistically significant relationship between higher ACT score and lower numbers of exacerbations in patients split into the various ACT subgroups [22, 23, 28,29,30,31,32].

ACT score and lung function

Twenty-five articles were identified which assessed the relationship between ACT score and lung function. Of these, eight publications did not fully meet the predefined inclusion criteria and were therefore subsequently excluded from data extraction.

There is a strong body of evidence supporting a relationship between improvement in ACT score and improvement in lung function, particularly with respect to forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1; Table 1). In total, 17 publications detailing studies that met the inclusion criteria reported lung function measurements [3, 11, 13, 15, 18, 27, 33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43], with some reporting multiple outcomes (e.g. FEV1 and forced vital capacity [FVC]) [15, 27, 36, 38].

Of the 14 publications reporting FEV1, seven reported statistically tested correlations between improvement in ACT score and improvement in FEV1 [3, 15, 27, 34,35,36,37]. Of these, five demonstrated statistically significant correlations, with coefficients ranging from 0.177 to 0.518, as calculated by different methods [3, 34,35,36,37]. This evidence was supported by the remaining seven studies, which tested the relationships between ACT score and FEV1 by linear regression, analysis of variance (ANOVA), or in subgroups of patients categorized according to ACT score or FEV1 [11, 13, 18, 38,39,40, 43]; of these seven articles, six reported statistically significant relationships [11, 13, 38,39,40, 43].

Three articles tested for a statistical correlation between improved asthma control as measured by increased ACT score and improvement in FVC [15, 33, 36], with only one demonstrating a notable relationship (correlation coefficient, ρ = 0.26, p = 0.01) [36]. The one publication that assessed FVC without a correlation test also reported a strong relationship (p = 0.000) [42].

ACT score and QoL

A total of seven articles reported HRQoL in asthma patients [28, 34, 44,45,46,47,48], all of which showed strong positive relationships between improvement in ACT score and improvement in Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ) score (Table 1). All seven studies published statistically significant results, five from correlation tests [28, 34, 44,45,46], and two derived from regression analyses [47, 48].

In total, seven studies reported general HRQoL in ACT subgroups, measuring HRQoL by the Short Form (12-item) Health Survey (SF-12) or the EuroQol five dimensions questionnaire (EQ-5D) [49,50,51,52,53,54,55]. In both questionnaires, a higher score indicates improved QoL.

For SF-12, a consistent trend was observed that individual physical and/or mental component scores were lower for the groups with asthma that was “not well controlled”. Statistically significant differences in individual SF-12 domain scores between patients with uncontrolled/not well-controlled versus controlled asthma (ACT score thresholds varied) were observed in three (physical component) [49, 53, 54] and two (mental component) studies [49, 52], respectively.

Guilbert et al. [54] performed bivariate and multivariate analyses on the relationship between asthma control (“well-controlled” [ACT score > 19] vs. “not well-controlled” [ACT score ≤ 19]) and SF-12 physical domain score, observing a negative relationship between ACT score ≤ 19 and SF-12 score. The mean differences in SF-12 scores between patients with “not well-controlled” and “well-controlled” asthma were − 7.0 and − 3.4 for the bivariate and multivariate analyses, respectively (both p < 0.001) [54].

Additionally, one study reported a significant difference in EQ-5D between patients with “not well-controlled” (ACT score < 20) and “well-controlled” (ACT score ≥ 20) asthma (EQ-5D scores, 0.7 vs. 0.9; p < 0.0001) [50]. This finding is of particular interest, given that the EQ-5D system may lack sensitivity which often does not correlate with underlying clinical measures [56, 57].

ACT score and sleep quality

In total, six articles reported on aspects of sleep quality, including instruments that measured daytime sleepiness and obstructive sleep apnea [45, 58,59,60,61,62]; three of these studies utilized multiple sleep quality instruments (Table 1) [58, 60, 62].

Of the four studies using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [45, 58, 60, 62], two reported notable, statistically significant correlations between improvement in ACT score and improvement in sleep quality (r = − 0.315, p < 0.001 and r = − 0.620, p < 0.001, respectively) [45, 58]. Additionally, Lv et al. [60] found that poor sleep quality, assessed by PSQI, was related to lower ACT score using regression analyses (β = − 0.87, p = 0.045).

A statistically significant relationship was also demonstrated between improvement in ACT score and improvement in sleep quality measured using the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Sleep Scale. Compared with patients who had an ACT score ≥ 20, those with a score < 20 had significantly higher scores in all components of the MOS Sleep Scale (all p < 0.001, F-values 19.1–109.0), corresponding to poorer sleep quality [61].

A relationship between the level of asthma control, as measured by ACT score, and improvement in sleep quality, as measured by the Sleep-5 questionnaire, was also reported, but the relationship was not tested for statistical significance [59].

Two studies reported that patients with lower ACT scores tended to have higher (worse) Epworth Sleepiness Scale scores, although no statistical analysis was performed [58, 62].

Regression analyses (unadjusted and adjusted) were performed in one study to determine the relationship between asthma control (measured by the ACT) and the Berlin Questionnaire for obstructive sleep apnea [60].

ACT score and productivity and activity levels

Out of a total of seven articles, five reported on the relationship between improvement in ACT score and improvement in productivity, as measured by the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire (WPAI) (Table 1) [49, 51, 53, 55, 63]. One study reported a negative correlation between ACT score and WPAI score (correlation varied between − 0.707 and − 0.750, statistical significance not reported) [63]. The other four studies reported higher work impairment in patients whose asthma was not well controlled (ACT score < 20), compared with those with well-controlled asthma (ACT score ≥ 20) [49, 51, 53, 55]. However, only one of these found that relationship to be statistically significant [49].

Two studies reported on the relationship between the level of asthma control, as measured by ACT score, and improvement in productivity using other measures (i.e. the Effort-Reward-Imbalance questionnaire, the Sheehan Disability Scale, and the Impact on Work Productivity Index [IMPALA]) [56, 57]. Of these, one study reported a statistically significant relationship between the subgroup with improved asthma control and productivity measured by the Sheehan Disability Scale and IMPALA [57].

ACT score and resource use and costs

In total, 17 publications reported on the relationship between ACT score and HRU (Table 1) [47, 49, 51, 53,54,55, 64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74].

One study reported a non-significant relationship between improvement in ACT score and both the ratio of maintenance to reliever medication dispensed, and inhaler nebulization rates [66].

A total of 16 studies examined relationships between reduction in unscheduled care and ACT score improvement from “not well controlled” to “well-controlled” asthma [47, 49, 51, 53,54,55, 67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76]. Statistically significant results were reported for unscheduled outpatient clinic visits by two studies [54, 74], for emergency department visits by five studies [54, 55, 71, 74, 75], for hospitalizations by three studies [55, 71, 72], for ‘urgent health care utilization’ by one study [69] and use of inhaled corticosteroids by one study [67].

In total, six studies reported on costs [50, 65, 70, 76,77,78], of which five reported relationships between asthma control subgroup and direct medical costs [50, 65, 70, 76, 77], and three with indirect medical costs [65, 77, 78]. However, only one study reported statistically significant results for direct medical costs [77].

The average cost (Euros [€)/month/patient) of well-controlled asthma versus “not well-controlled” asthma was reported as €28 versus €140 in France and €77 versus €252 in Spain [50]. In Spain, indirect costs were significantly higher in older patients (41–65 years, €405.08), patients with more severe disease (€698.95), and patients with more poorly controlled asthma (€466.86) [65]. Mean per-patient annual costs of asthma management for patients with derived ACT scores of < 15, 15–19 and ≥ 20 were reported as, in the Asia-Pacific, US$861, US$319 and US$193 [70]; and in Europe, €1604, €512, and €232 [76]. Patients with asthma control spent S$48 (US $36) more per doctor visit on asthma drugs (p < 0.01) but incurred S$65 (US$48) less per doctor visit in total costs (p < 0.01) than those with suboptimal asthma control [77].

The data suggest that asthma that was not well controlled (ACT score < 20) led to higher direct medical costs [65, 77], higher unscheduled care costs [70, 76], and higher total societal costs of asthma [50], while data on indirect costs suggest that “not well-controlled” asthma (ACT score < 20) leads to higher indirect medical costs [77, 78], and higher cost of workdays lost [65].

Discussion

This review aimed to qualitatively assess the link between ACT score and key asthma outcomes through a targeted review of the available literature. Substantial evidence was identified for relationships between ACT score and ACQ score, lung function, and asthma-related QoL; moderate evidence was obtained for relationships between ACT score and rescue medication use, exacerbations, sleep quality, and work and productivity; limited evidence was identified for relationships between ACT score and general health-related QoL, HRU, and healthcare costs. While links to reductions in the use of rescue medication and the number of asthma exacerbations were also reported, there was limited or no evidence to suggest that there is a relationship between ACT score and general HRQoL, HRU, and healthcare costs.

Overall, these findings support the use of the ACT in a clinical setting, as a valid measure of disease control and associated patient outcomes, including ongoing symptomology and future risk. They also support the clinical use of the ACT to guide the appropriate management of patients with asthma, including when and how to select between alternative treatments. Additionally, the available evidence provides a foundation for the use of the ACT as a primary or secondary endpoint in clinical trials, allowing investigators to gauge accurately the effectiveness of a treatment.

The overall strength of this review is that it collates the published relationships between ACT score and a broad range of clinical outcomes into a coherent whole. By aiding our understanding of how ACT score is reflective of the different aspects of patients’ asthma experience, this review provides support for its use as a viable measure for other outcomes.

Limitations include the targeted nature of the literature search, which may not have encompassed the full body of literature on the correlation being investigated, and the presence of large differences in scientific rigor and reporting standards between the included articles. Additionally, the statistical power may have been inadequate in some of the evaluated studies, either by being insufficiently powered to evaluate the relationships between ACT score and the outcomes of interest, or overpowered to the extent such as a weak relationship became highly statistically significant.

With respect to future work, the exploratory setup of this research provides a characterization of the topics on which scientific data regarding the ACT are present or absent. As such, the current report provides a starting point to explore and corroborate these findings in future research initiatives on the value of ACT scores in real-world clinical settings. More studies evaluating relationships between ACT score and general HRQoL, healthcare costs, and resource use are also needed, as well as additional research into relationships in populations with differing levels of asthma severity.

Conclusion

Despite some limitations inherent to the nature of a targeted literature review, this report provides an informative qualitative assessment of the available literature on the relationships between ACT score and a broad range of outcomes of interest, supporting the use of the ACT in clinical practice and trial settings.

Availability of data and materials

All data used in this review were taken from publicly available articles, and can be found at the relevant journal websites.

Abbreviations

- ACQ:

-

Asthma Control Questionnaire

- ACT:

-

Asthma Control Test

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- AQLQ:

-

Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire

- ATS:

-

American Thoracic Society

- CHEST:

-

Annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians

- EQ-5D:

-

EuroQol five dimensions questionnaire

- ERS:

-

European Respiratory Society

- FEV1 :

-

Forced expiratory volume in 1 s

- FVC:

-

Forced vital capacity

- HRQoL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- HRU:

-

Healthcare resource use

- IMPALA:

-

Impact on Work Productivity Index

- MOS:

-

Medical Outcomes Study

- PSQI:

-

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- SABA:

-

Short-acting beta agonist

- SF-12:

-

Short Form (12-item) Health Survey

- WPAI:

-

Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire

References

Global Initiative for Asthma. 2018 GINA report: global strategy for asthma management and prevention 2018. https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/2018-GINA.pdf. Accessed 26 June 2018.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Expert panel report 3: guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. 2007. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/guidelines/asthgdln.pdf. Accessed 26 June 2018.

Nathan RA, Sorkness CA, Kosinski M, Schatz M, Li JT, Marcus P, et al. Development of the asthma control test: a survey for assessing asthma control. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:59–65.

Jia CE, Zhang HP, Lv Y, Liang R, Jiang YQ, Powell H, et al. The asthma control test and asthma control questionnaire for assessing asthma control: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:695–703.

Adachi M, Goldfrad C, Jacques L, Nishimura Y. Efficacy and safety comparison: fluticasone furoate and fluticasone propionate, after step down from fluticasone furoate/vilanterol in Japanese patients with well-controlled asthma, a randomized trial. Respir Med. 2016;120:78–86.

Manfrin A, Tinelli M, Thomas T, Krska J. A cluster randomised control trial to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the Italian medicines use review (I-MUR) for asthma patients. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:300.

Woodcock A, Vestbo J, Bakerly ND, New J, Gibson JM, McCorkindale S, et al. Effectiveness of fluticasone furoate plus vilanterol on asthma control in clinical practice: an open-label, parallel group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;390:2247–55.

Luque E, Guerrero P, Gόmez-Bastero A, Romero C, Mechbal L, Montemayor T. Concordance between the new questionnaires to evaluate asthma control. Eur Respir J. 2011;38(Suppl 55):4026.

Malinovschi A, Pizzimenti S, Sciascia S, Heffler E, Badiu I, Rolla G. Exhaled breath condensate nitrates, but not nitrites or FENO, relate to asthma control. Respir Med. 2011;105:1007–13.

Ruchiwit P, Kanitsap A, Petvipusit W. The comparison of three asthma control questionnaires and peak expiratory flow variability. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:abstr A4963.

Schatz M, Sorkness CA, Li JT, Marcus P, Murray JJ, Nathan RA, et al. Asthma control test: reliability, validity, and responsiveness in patients not previously followed by asthma specialists. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:549–56.

Schuler M, Faller H, Wittmann M, Schultz K. Asthma control test and asthma control questionnaire: factorial validity, reliability and correspondence in assessing status and change in asthma control. J Asthma. 2016;53:438–45.

Zhou X, Ding FM, Lin JT, Yin KS. Validity of asthma control test for asthma control assessment in Chinese primary care settings. Chest. 2009;135:904–10.

Khalili B, Boggs PB, Shi R, Bahna SL. Discrepancy between clinical asthma control assessment tools and fractional exhaled nitric oxide. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;101:124–9.

Wojtczak HA, Wachter AM, Lee M, Burns L, Yusin JS. Understanding the relationship among pharmacoadherence measures, asthma control test scores, and office-based spirometry. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;109:103–7.

Yusin JS, Wachter A, Wojtczak H, Lee M. Use of the asthma medication ratio and the rescue index in following asthma control in veterans diagnosed with asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2011;107:abstr A7.

Cajigal S, Wells KE, Peterson EL, Ahmedani BK, Yang JJ, Kumar R, et al. Predictive properties of the asthma control test and its component questions for severe asthma exacerbations. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5:121–7 e2.

Melosini L, Dente FL, Bacci E, Bartoli ML, Cianchetti S, Costa F, et al. Asthma control test (ACT): comparison with clinical, functional, and biological markers of asthma control. J Asthma. 2012;49:317–23.

Merchant RK, Inamdar R, Quade RC. Effectiveness of population health management using the propeller health asthma platform: a randomized clinical trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4:455–63.

Moran A, Beckert L. Self-identified well controlled asthma and sub-optimal asthma control test: TP 079. Respirology. 2014;19:83.

Özgür ES, Özge C, Ilvan A, Nayci SA. Assesment of long-term omalizumab treatment in severe allergic asthma. Eur Respir J. 2012;40 Suppl 56:abstr P225.

Schatz M, Kosinski M, Yarlas A, Hanlon J, Jhingran P. The minimally important difference (MID) of the Asthma Control Test (ACT) administered by telephone. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(Suppl 152):582.

Schatz M, Kosinski M, Yarlas AS, Hanlon J, Watson ME, Jhingran P. The minimally important difference of the Asthma Control Test. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:719–23 e1.

Terzano C, Cremonesi G, Girbino G, Ingrassia E, Marsico S, Nicolini G, et al. 1-year prospective real life monitoring of asthma control and quality of life in Italy. Respir Res. 2012;13:112.

Woodcock A, Bakerly ND, New JP, Gibson JM, Wu W, Vestbo J, et al. The Salford lung study protocol: a pragmatic, randomised phase III real-world effectiveness trial in asthma. BMC Pulm Med. 2015;15:160.

Kwon J-W, Kim S-H, Kim T-B, Park H-W, Chang Y-S, Jang A-S, et al. Relationship between asthma control test and the improvement of FEV1 in treated patients with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:abstr A5751.

Vega JM, Badia X, Badiola C, López-Viña A, Olaguíbel JM, Picado C, et al. Validation of the Spanish version of the asthma control test (ACT). J Asthma. 2007;44:867–72.

Ban GY, Ye YM, Lee Y, Kim JE, Nam YH, Lee SK, et al. Predictors of asthma control by stepwise treatment in elderly asthmatic patients. J Korean Med Sci. 2015;30:1042–7.

Busse WW, Trzaskoma B, Omachi TA, Canvin J, Rosen K, Chipps BE, et al. Evaluating xolair persistency of response after long-term therapy (XPORT). Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:abstr A6576.

Ko FW, Hui DS, Leung TF, Chu HY, Wong GW, Tung AH, et al. Evaluation of the asthma control test: a reliable determinant of disease stability and a predictor of future exacerbations. Respirology. 2012;17:370–8.

Krasnodebska P, Hermanowicz-Salamon J, Domagala-Kulawik J, Chazan R. Factors influencing asthma course and the degree of control in the patients assessed with own questionnaire and asthma control test (ACT). Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2012;80:198–208.

Tay T, Radhakrishna N, Hore-Lacey F, Hoy R, Dabscheck E, Hew M. Protocolised difficult asthma assessment improves asthma outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:A1741.

Jumbo J, Adeniyi BO, Ikuabe PO, Erhabor GE. The asthma control test and its relationship with lung function parameters. Afr J Respir Med. 2014;9:24–7.

Ozoh OB, Okubadejo NU, Chukwu CC, Bandele EO, Irusen EM. The ACT and the ATAQ are useful surrogates for asthma control in resource-poor countries with inadequate spirometric facilities. J Asthma. 2012;49:1086–91.

Papakosta D, Latsios D, Manika K, Porpodis K, Kontakioti E, Gioulekas D. Asthma control test is correlated to FEV1 and nitric oxide in Greek asthmatic patients: influence of treatment. J Asthma. 2011;48:901–6.

Rodrigo GJ, Arcos JP, Nannini LJ, Neffen H, Broin MG, Contrera M, et al. Reliability and factor analysis of the Spanish version of the asthma control test. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;100:17–22.

Shirai T, Furuhashi K, Suda T, Chida K. Relationship of the asthma control test with pulmonary function and exhaled nitric oxide. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;101:608–13.

Alvarez-Gutierrez FJ, Medina-Gallardo JF, Pérez-Navarro P, Martín-Villasclaras JJ, Martin Etchegoren B, Romero-Romero B, et al. Relationship of the asthma control test (ACT) with lung function, levels of exhaled nitric oxide and control according to the global initiative for asthma (GINA). Arch Bronconeumol. 2010;46:370–7.

Grammatopoulou E, Haniotou A, Evangelodimou A, Tsamis N, Myrianthefs P, Baltopoulos G. Factors associated with asthma control in patients with stable asthma. Eur Respir J. 2011;38(Suppl 55):1297.

Gurkova E, Popelkova P. Validity of asthma control test in assessing asthma control in Czech outpatient setting. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2015;23:286–91.

Pisi R, Tzani P, Aiello M, Martinelli E, Marangio E, Nicolini G, et al. Small airway dysfunction by impulse oscillometry in asthmatic patients with normal forced expiratory volume in the 1st second values. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2013;34:e14–20.

Shameem M, Ahmad A, Saad M, Bhargava R, Fatima N. A randomised, double-blind, parallel-group study to determine the bronchodilator property of nigella sativa extract in patients of bronchial asthma. Respiration. 2013;85:594.

Zhou X, Ding FM, Lin JT, Yin KS, Chen P, He QY, et al. Validity of Asthma Control Test in Chinese patients. Chin Med J (Engl). 2007;120:1037–41.

Bereznicki BJ, Peterson GM, Jackson SL, Walters H, Fitzmaurice K, Gee P. Pharmacist-initiated general practitioner referral of patients with suboptimal asthma management. Pharm World Sci. 2008;30:869–75.

Hayat E, BörekçI S, Gemicioglu B. Reflux, allergic rhinitis, and sleep disorders with asthma control and quality of life. J Clin Anal Med. 2014;5:453–6.

Schatz M, Mosen DM, Kosinski M, Vollmer WM, Magid DJ, O'Connor E, et al. Validity of the asthma control test completed at home. Am J Manag Care. 2007;13:661–7.

Eilayyan O, Gogovor A, Mayo N, Ernst P, Ahmed S. Predictors of perceived asthma control among patients managed in primary care clinics. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:55–65.

Sundbom F, Malinovschi A, Lindberg E, Alving K, Janson C. Effects of poor asthma control, insomnia, anxiety and depression on quality of life in young asthmatics. J Asthma. 2016;53:398–403.

Adamek L, Demoly P, Annunziata K, Gubba L. Update on asthma control in Europe: results of a 2010 survey. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:abstr A4757.

Chouaid C, Calvo CE, Brosa M, Doz M, Gueron B. Quality of life and economic impact of asthma control in France and Spain. First results of the EU-COAST study. Value Health. 2010;13:abstr A320.

Demoly P, Annunziata K, Gubba E, Adamek L. Repeated cross-sectional survey of patient-reported asthma control in Europe in the past 5 years. Eur Respir Rev. 2012;21:66–74.

DiBonaventura MD, Arakawa I, Fukuda T, Nagae T, Wagner JS, Stankus A. The effect of uncontrolled asthma on health-related quality of life and resource use in Japan and the United States. Value Health. 2010;13:A561.

Gueron B, Annunziata K, Castillo G. The effect of asthma control on healthcare control resource, work productivity and activity impairment in 5 European countries. Allergy Eur J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;64:437–8.

Guilbert TW, Garris C, Jhingran P, Bonafede M, Tomaszewski KJ, Bonus T, et al. Asthma that is not well-controlled is associated with increased healthcare utilization and decreased quality of life. J Asthma. 2011;48:126–32.

Vietri J, Burslem K, Su J. Poor asthma control among US workers: health-related quality of life, work impairment, and health care use. J Occup Environ Med. 2014;56:425–30.

Devlin NJ, Krabbe PFM. The development of new research methods for the valuation of EQ-5D-5L. Eur J Health Econ. 2013;14:1–4.

Payakachat N, Ali MM, Tilford JM. Can the EQ-5D detect meaningful change? A Systematic Review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33:1137–54.

Campos FL, de Bruin PFC, Pinto TF, da Silva FGC, Pereira EDB, de Bruin VMS. Depressive symptoms, quality of sleep, and disease control in women with asthma. Sleep Breath. 2017;21:361–7.

Braido F, Baiardini I, Ghiglione V, Fassio O, Bordo A, Cauglia S, et al. Sleep disturbances and asthma control: a real life study. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2009;27:27–33.

Lv N, Xiao L, Camargo CA Jr, Wilson SR, Buist AS, Strub P, et al. Abdominal and general adiposity and level of asthma control in adults with uncontrolled asthma. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11:1218–24.

Sanz de Burgoa V, Rejas J, Ojeda P. Investigators of the Coste Asma study. Self-perceived sleep quality and quantity in adults with asthma: findings from the CosteAsma Study. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2016;26:256–62.

Watanabe Y, Yokoe T, Fujiwara A, Uchida Y, Kimura T, Fukuda Y, et al. Association between asthma control and sleep condition. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:abstr A5999.

Antonova E, Trzaskoma B, Omachi TA, Schatz M. Poor asthma control is associated with overall daily activity impairment: 3-year data from the EXCELS study of omalizumab. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:abstr AB14.

Hartmann B, Leucht V, Loerbroks A. Work stress, asthma control and asthma-specific quality of life: initial evidence from a cross-sectional study. J Asthma. 2017;54:210–6.

Ojeda P, Sanz de Burgoa V; Coste Asma Study. Costs associated with workdays lost and utilization of health care resources because of asthma in daily clinical practice in Spain. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2013;23:234–41.

Lee KH, Sim YF. Does the preventer to reliever inhaler dispensing ratio correlate with nebulisation rates for asthma patients in a primary care setting? A cross-sectional study. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2014;143(Suppl 9):S385.

Adams R, Appleton S, Wilson D, Ruffin R. Correlates of poor asthma control in a population sample. Respirology. 2010;15:abstr A46.

Al-Zahrani JM, Ahmad A, Al-Harbi A, Khan AM, Al-Bader B, Baharoon S, et al. Factors associated with poor asthma control in the outpatient clinic setting. Ann Thorac Med. 2015;10:100–4.

Ko FWS, Hui DSC, Leung T-F, Chu JHY, Wong GWK, Ng SSS, et al. Asthma control test: cut off values of control according to GINA guideline and its ability to predict exacerbations and treatment decisions. Eur Respir J. 2011;38(Suppl 55):p940.

Lai CKW, Kuo S-H, de Guia T, Lloyd A, Williams AE, Spencer MD, et al. Asthma control and its direct healthcare costs: findings using a derived asthma control test™ score in eight Asia-Pacific areas. Eur Respir Rev. 2006;15:24–9.

Lee T, Kim J, Kim S, Kim K, Park Y, Kim Y, et al. Risk factors for asthma-related healthcare use: longitudinal analysis using the NHI claims database in a Korean asthma cohort. PLoS One. 2014;9:e112844.

Masaki H, Iikura M, Ro S, Miyoshi S, Hojo M, Sugiyama H. Retrospective analysis to identify predictors of re-hospitalization of asthmatic patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:abstr A1341.

Prabhakaran L, Jantan SA, Low W, Mun WW, Abisheganaden J. A pilot study to evaluate outcome of asthma patient's right sighted from an institution to primary care provider (PCP). Respirology. 2011;16:199.

Reddel H, Sawyer S, Flood P, Everett P, Peters M. Patterns of asthma control and inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) use in Australians living with asthma. Respirology. 2014;19:77.

Vervloet D, Pribil C, Dumur JP, Godard P, Salmeron S, Serrier P, et al. Factors associated with poorly controlled asthma among adults in France. Rev Fr Allergol. 2014;54:428–37.

Vervloet D, Williams AE, Lloyd A, Clark TJH. Costs of managing asthma as defined by a derived asthma control test™ score in seven European countries. Eur Respir Rev. 2006;15:17–23.

Nguyen HV, Nadkarni NV, Sankari U, Mital S, Lye WK, Tan NC. Association between asthma control and asthma cost: results from a longitudinal study in a primary care setting. Respirology. 2017;22:454–9.

Ojeda P, Sanz-De-Burgoa V. Costs associated with health care utilisation due to asthma in a Spanish population. Allergy Eur J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;67:167.

Acknowledgements

Pharmerit International would like to thank Anne Marie Trip and Susan Tempelaar for their assistance with this study. Trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Medical writing support in the form of development of the draft outline and manuscript drafts in consultation with the authors, editorial suggestions to draft versions of this paper, assembling tables and figures, collating author comments, copyediting, referencing and graphic services was provided by David Mayes, MChem and Samantha McKenna, BSc (Hons) of Gardiner-Caldwell Communications (Macclesfield, UK), and was funded by GlaxoSmithKline plc.

Funding

This study was designed and funded by GlaxoSmithKline plc. (GlaxoSmithKline plc. Study number HO-17-18170). Employees of GlaxoSmithKline plc. were involved in the study concept and design, data analysis, and preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CA and BvD (guarantor) conceived and designed the literature review design. BvD and JB collected, analyzed and interpreted the data. CA supervised the project. HS, AH, LN, and JB were involved in the conception/design and data analysis/interpretation of the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final version to be published.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

HS, LN, and AH are employees of/hold stocks in GlaxoSmithKline plc. CA is a paid employee of Pharmerit International, the vendor who conducted the research on behalf of the sponsor. BvD and JB were employees of Pharmerit International at the time of the research. Trademarks are the property of their respective owners.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

At the time of the research, Bas C.P. van Dijk and Janita S. Balradj were employees of Pharmerit International.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

van Dijk, B.C.P., Svedsater, H., Heddini, A. et al. Relationship between the Asthma Control Test (ACT) and other outcomes: a targeted literature review. BMC Pulm Med 20, 79 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-020-1090-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-020-1090-5