Abstract

Background

There is a lack of national-level research on alcohol consumption and the epidemiology of alcoholic liver disease (ALD) in South Korea. This study aims to address the critical public health issue of ALD by focusing on its trends, incidence, and outcomes, using nationwide claims data.

Methods

Utilizing National Health Insurance Service data from 2011 to 2017, we calculated the population's overall drinking amount and the incidence of ALD based on ICD-10 diagnosis codes.

Results

From 2011 to 2017 in South Korea, social drinking increased from 15.7% to 16.5%, notably rising among women. High-risk drinking remained around 16.4%, decreasing in men aged 20–39 but not decreased in men aged 40–59 and steadily increased in women aged 20–59. The prevalence of ALD in high-risk drinkers (0.97%) was significantly higher than in social drinkers (0.16%). A 3-year follow-up revealed ALD incidence of 1.90% for high-risk drinkers and 0.31% for social drinkers. Women high-risk drinkers had a higher ALD risk ratio (6.08) than men (4.18). The economic burden of ALD was substantial, leading to higher healthcare costs and increased hospitalization. Progression rates to liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in ALD patients were 23.3% and 2.8%, respectively, with no gender difference in cirrhosis progression.

Conclusions

The study revealed a concerning rise in alcohol consumption among South Korean women and emphasizes the heightened health risks and economic burdens associated with high-risk drinking, especially concerning ALD and its complications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In South Korea, chronic hepatitis B and alcohol are the most common causes of liver disease in South Korea, accounting for 60–80% and 13–14.5% of cases [1,2,3]. Recently, there has been a decline in hepatitis B and C, while the prevalence of alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is gradually increasing [4,5,6]. This upward trend is concerning due to the potential for ALD to progress to severe liver conditions, including cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [7, 8]. Alcohol consumption has a well-documented relationship with the incidence of alcoholic liver disorders. Alcoholic liver disease is a significant issue in Asia, where trends in alcohol consumption are particularly alarming. In China, the rate of alcohol consumption is increasing faster than in other regions of the world, highlighting a growing public health concern [9]. Additionally, Central Asia has recorded the highest number of alcohol-attributable liver cirrhosis Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) per 100,000 people for both men and women [10]. Research has shown that genetic factors, such as the prevalence of certain alcohol dehydrogenase and aldehyde dehydrogenase enzyme variants in Asians, contribute to a higher susceptibility to alcoholic liver diseases compared to other populations. This genetic predisposition results in a faster conversion of alcohol into acetaldehyde, a toxic metabolite, and a slower process of clearing it from the body, leading to increased liver damage from smaller amounts of alcohol.

Traditionally, alcohol has played a pivotal role in both social and business settings in South Korea. Drinking patterns in South Korea are characterized by a mix of solitary and social drinking, often involving both mixed and single-type alcohol consumption. Social drinking is commonly practiced in a variety of settings, including family gatherings, pubs, and restaurants, reflecting its integral role in both personal and professional interactions. This pattern is deeply embedded in the culture, where drinks like soju and beer are frequently consumed in combination during social occasions to facilitate bonding and business negotiations. On the other hand, solitary drinking has been on the rise, often driven by stress or social isolation, marking a shift in traditional drinking behaviors. These changes are not just social trends; they carry significant implications for public health, particularly in the incidence and progression of ALD. Additionally, the landscape of alcoholic beverage policies in South Korea has seen adjustments during the study period. These include modifications in taxation, advertising regulations, and sales restrictions aimed at curbing excessive alcohol consumption.

Unlike other viral hepatitis cases, ALD has identifiable triggering factors and is significantly influenced by social and economic policies [11]. Therefore, early identification of drinking status can aid in ALD prevention through abstinence education, effectively averting progression to liver cirrhosis or HCC [12]. Understanding the current status of drinking rates and their direct impact on ALD epidemiology is crucial for developing effective public health interventions and policies [13]. Unfortunately, no large-scale study representative of South Korea's ALD epidemiology has been conducted to date [1, 14]. This study aims to investigate drinking rates and ALD epidemiology in South Korea, examining patterns of change over time using national cohort and National Health Insurance data. Additionally, in line with existing reports that alcohol consumption varies by age and gender [15,16,17], we have conducted further stratified analysis based on these demographic factors

Methods

Data source and study population

In this study, two databases were utilized. First, to comprehend the current drinking landscape in South Korea and assess the risk levels based on drinking rates, we analyzed examination data from the National Health Insurance Corporation (National Health Insurance Service-Health Screening Cohort; NHIS-HEALs). Due to security and data capacity limitations, the complete NHIS-HEALs dataset was unavailable. Consequently, a representative sample cohort, constituting 10% of the NHIS population, was randomly selected annually from 2011 to 2017, as detailed in Supplementary Table 1. This sample cohort accurately mirrors the broader South Korean population, deliberately chosen to match the age and gender distribution of the entire NHIS-HEALs. Second, the epidemiology of patients with ALD was further validated using claims data in conjunction with NHIS-HEALs. Data reliability was ensured through two methods. Initially, the ALD incidence rate was calculated and compared from NHIS-HEALs and claims data, confirming a consistent pattern. Additionally, the proportion of high-risk drinkers was compared between National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data and NHIS-HEALs, demonstrating consistent proportions of high-risk drinkers in the two cohorts.

Both databases contain anonymized data, including demographic details and claims information aligned with the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10). The Institutional Review Board of Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital approved the current study (IRB No. SCHBC 2023–05-007, approval date 23-May-2023). Informed consent was waived by the IRB since only de-identified information was utilized. Our study adhered to the ethical guidelines of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

Classification of alcohol drinking

In South Korea, a national health screening is conducted every two years, during which citizens are required to fill out a health questionnaire. The questionnaire includes the following items related to alcohol consumption:

-

1)

On average, how many days per week do you drink alcohol?

-

2)

On days when you drink, how much do you typically consume in a day? (number of drinks)

(Calculate using each type of drink's standard serving size. Note that one can of beer (355 cc) is equivalent to 1.6 standard beer servings.)

Based on these survey items, high-risk drinking was categorized as consuming alcohol more than twice weekly, with men consuming over 7 standard drinks and women more than 5, following the guidelines of the South Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare [18]. A standard drink in Korea is defined as containing 7 g of pure alcohol, in accordance with South Korean alcohol consumption guidelines [19]. For the purpose of comparison, social drinkers served as the control group for high-risk drinking. Social drinkers were identified as individuals who drink once a week, with men having up to 6 standard drinks and women up to 4 standard drinks [18].

Outcomes

The study focused on examining the prevalence and incidence of ALD, cirrhosis, and HCC. ALD was identified in patients who received outpatient treatment more than twice or were admitted to the hospital at least once with a primary diagnosis coded under ICD-10 codes K70 (K700, K701, K702, K703, K704, and K709). Liver cirrhosis was categorized using ICD-10 codes K74, K702, and K703, while HCC was defined by the code C220. Mortality encompassed all reported deaths, regardless of the cause. Incidence referred to the emergence of a new case of the outcome during a 3-year follow-up of the sample cohort.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as means with standard deviations (SDs), while categorical variables were expressed as percentages, unless otherwise specified. Group differences were assessed using Student's t-test for continuous variables and the χ2 test for categorical variables. We conducted age-period-cohort (APC) analyses to identify changes in outcomes over time, accounting for the influences of age and birth cohort. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and R version 3.2.3 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, http://www.Rproject.org). A P value of less than 0.05, determined from a two-sided test, was considered indicative of statistical significance.

Results

Alcohol consumption trends in South Korea

The proportion of social drinkers was 15.7% in 2011, gradually increasing thereafter and reaching 16.5% in 2017 (p for trend < 0.001) (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 1). For men, the proportion of social drinkers peaked at 16.8% in 2014 and has been decreasing since, while for women, it has shown a consistent upward trend each year. Meanwhile, high-risk drinkers remained constant at about 16.5% from 2011 to 2017. Although the number of high-risk drinkers among men gradually decreased, the proportions among women increased annually. When analyzed by age and gender, the proportion of high-risk drinkers decreased among men aged 20–39, while it does not decrease among men aged 40–59. In women, the number of high-risk drinkers increased each year across all age groups from 20 to 59. To validate the reliability of NHIS-HEALs data, the proportion of high-risk drinkers was cross-verified with National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data, revealing consistent proportions in both cohorts (Supplementary Table 2).

Consequences of alcoholic liver disease caused by alcohol consumption

Subsequently, we assessed the occurrence of ALD, liver cirrhosis, HCC, and mortality based on the volume of alcohol consumed. The prevalence of ALD among high-risk drinkers was 0.97%, significantly surpassing the prevalence of 0.16% among social drinkers (Supplementary Table 3). Over a 3-year follow-up, the incidence of ALD in high-risk drinkers reached 1.90%, while in social drinkers, it was 0.31% (Table 2). In both groups, ALD incidence rose with age and was higher in men than in women. The prevalence of cirrhosis was 0.19% among high-risk drinkers, exceeding the 0.10% among social drinkers (Supplementary Table 4). The 3-year follow-up also revealed a higher incidence of cirrhosis in high-risk drinkers (0.43% vs. 0.19%) (Table 2). The patterns for the prevalence (Supplementary Table 5) and incidence (Table 4) of HCC followed a similar trend, with significantly higher rates in high-risk drinkers compared to social drinkers (prevalence: 0.04% vs. 0.03%, incidence: 0.13% vs. 0.08%). Furthermore, 3-year mortality was elevated in high-risk drinkers (0.50% vs. 0.24%) (Supplementary Table 6).

Age–period–cohort analysis

Our APC analysis of ALD, liver cirrhosis, and HCC over a three-year span reveals distinct trends among different age groups and drinking behaviors (Fig. 1). For high-risk drinkers, the incidence of ALD decreases with age, with the highest rates in older age groups. Social drinkers show consistently lower incidence rates across all conditions compared to high-risk drinkers. The incidence of liver cirrhosis and HCC is higher in older age groups for both high-risk and social drinkers, with a more pronounced increase among high-risk drinkers. Overall, while high-risk drinkers exhibit a gradual decline in incidence rates over time, social drinkers maintain relatively stable and lower rates across all age groups and conditions.

Vulnerability of females to alcoholic liver disease

Stratified by gender, we computed the risk ratios (RRs) for ALD, cirrhosis, and HCC in high-risk drinkers compared to social drinkers. Compared to social drinkers, the risk of developing ALD was higher in women (RR 6.08) than in men (RR 4.18) (Supplementary Fig. 2A). Similarly, the risk of developing liver cirrhosis (women 2.31, men 1.74; Supplementary Fig. 2B) and HCC (women 1.48, men 1.25; Supplementary Fig. 2C) was determined to have a higher RR value in women than in men.

Epidemiology of alcohol-associated liver disease and economic burden

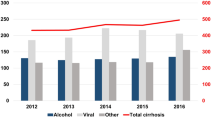

Subsequently, we computed epidemiological data and economic costs associated with ALD using claims data. The incidence of ALD showed a yearly decline, decreasing from 0.39% in 2012 to 0.33% in 2017, with a more significant decrease observed in men compared to women (Supplementary Table 7). To validate the reliability of the claim data, we compared the NHIS-HEALs cohort with ALD incidence and confirmed that the trends in the two cohorts were consistent. When ALD was categorized into detailed disease codes, the proportion of relatively mild diseases such as alcoholic fatty liver, ALD, and unspecified decreased, while the proportion of liver cirrhosis increased from 16 to 27% (Fig. 2). Comparing the healthcare utilization of ALD patients with the control group, the ALD group exhibited significantly higher total medical costs and drug costs than the control group (Table 3). Additionally, the number of outpatient visits and hospitalization days in the ALD group exceeded those of the control group (Table 3, Supplementary Fig. 3A/3B). This discrepancy appears to be linked to the higher comorbidity rate in the ALD group compared to the control group (Supplementary Table 8).

Natural history of alcohol-associated liver disease

Finally, we computed the rate of progression to liver cirrhosis or HCC in individuals diagnosed with ALD (Table 4). Over a 3-year follow-up period, the progression rates for liver cirrhosis and HCC in individuals with ALD were 23.3% and 2.8%, respectively. Notably, there was no significant difference in the rate of progression from ALD to liver cirrhosis between men and women (men 21.7%, women 21.7%; p = 0.382).

Discussion

Our study’s key findings include the gradual increase in social drinking, rising rates of high-risk drinking in women, gender and age-specific variations in alcohol consumption patterns, and the concerning association of high-risk drinking with the prevalence and incidence of ALD, liver cirrhosis, HCC, and mortality.

The primary finding of this study is the gradual increase in the proportion of social drinkers in South Korea. To ensure the reliability of this observation, alternative definitions, such as those who drink once a week, were explored, revealing a consistent pattern (Supplementary Table 9). We posit that two sociological factors in South Korea contribute to this trend. First, the absence of stringent regulations on alcohol advertising or broadcasting allows for the widespread portrayal of drinking scenes in public broadcasts and on platforms like YouTube, fostering a relaxed and favorable attitude towards drinking [20]. Also, the increase in alcohol consumption is influenced by the extensive reach of media and advertising. Alcohol brands frequently employ popular celebrities and K-pop idols in their marketing strategies, which are prominently displayed across diverse media platforms, including television and social media. Such advertisements portray alcohol consumption as an appealing aspect of a glamorous lifestyle, which resonates strongly with young audiences. Second, the increasing popularity of low-alcohol beverages, particularly among younger demographics, compounds the issue [21].

In terms of regulatory efforts, South Korea has established policies such as imposing taxes on alcoholic beverages and regulating sales times to control alcohol consumption. However, the enforcement of these policies is often lax, and specific regulations aimed at curbing alcohol advertising are insufficiently rigorous. This creates a regulatory environment where alcohol is both easily accessible and affordably priced, further encouraging its consumption among the youth. We suggest that the existing policies need to be strengthened with stricter advertising restrictions and more consistent enforcement of alcohol sales regulations.

The secondary finding is an increase in the number of high-risk drinkers among women. The overall rise of high-risk drinking among women is not exclusive to South Korea but represents a global phenomenon [22,23,24]. These changes might be influenced by evolving sociocultural dynamics, such as more women participating in traditionally male-dominated professional environments, possibly adopting associated social drinking habits. Moreover, marketing strategies targeted at women by alcohol companies also play a significant role. These campaigns often promote alcoholic beverages as symbols of modernity and independence, appealing particularly to a younger, female audience. Additionally, the increasing stress levels due to rapid socio-economic changes in the country could differentially influence drinking behaviors between genders. Women might use alcohol as a coping mechanism differently than men, which warrants further exploration [25, 26].

Our APC analysis indicate that the incidence of ALD, liver cirrhosis, and HCC varies significantly not only with gender, but also with age. Younger individuals, particularly those aged 20–39, show lower incidence rates of these conditions compared to older age groups. This can be attributed to the cumulative effects of long-term alcohol consumption, which typically manifests in more severe liver conditions over time. As people age, the prolonged exposure to alcohol and its hepatotoxic effects increase the likelihood of developing ALD and its complications.

Another important finding of our study is the notable increase in the proportion of liver cirrhosis cases within the spectrum of ALD. Upon manifestation of ALD, our study revealed a 23.3% probability of progressing to liver cirrhosis within 3 years, a figure consistent across both men and women and comparable to findings in other countries [27]. Alcoholic liver cirrhosis stands as a significant global public health concern, with an estimated 25% of cirrhosis-related deaths worldwide attributed to alcohol in 2019 [24, 28]. Recently observed shifts in South Korea, where the etiology of chronic liver disease is transitioning from viral hepatitis to ALD, emphasize the imperative for sustained attention and more effective treatments for alcoholic liver cirrhosis [8, 29, 30].

Additionally, our study demonstrated the vulnerability of females to ALD. The higher RR of developing ALD, cirrhosis, and HCC in women compared to men among high-risk drinkers aligns with findings in other studies [31]. We posit that the heightened vulnerability of women to alcohol stems from a combination of biological and physiological factors. Women, on average, have a higher body fat percentage and less body water, resulting in a more concentrated presence of alcohol in their bloodstream after consuming similar amounts as men. This prolonged exposure contributes to more significant liver damage over time [32, 33]. Additionally, women exhibit lower levels of alcohol dehydrogenase, the enzyme responsible for metabolizing alcohol, resulting in an extended duration of alcohol presence in their system, exposing the liver to harmful metabolites for prolonged periods [34]. Hormonal differences, particularly involving estrogen, may enhance women's susceptibility to alcohol-induced liver injury [34, 35]. Lastly, nutritional variances and social factors also contribute to women's heightened vulnerability to ALD. Social stigma and other barriers may lead women to delay seeking treatment, resulting in more advanced liver disease at the time of diagnosis [36, 37].

In the case of ALD, psychiatric alcohol abstinence treatment is essential. In South Korea, only about 9% of ALD patients, regardless of gender, receive formal psychiatric treatment, and this percentage is further decreasing each year (Supplementary Fig. 4). The information regarding population coverage, treatment coverage (e.g., alcohol use disorder and treatment), and copayment of these patients is listed in Supplementary Table 10. Lastly, the differences in healthcare utilization between ALD and HCC are notable. Patients with ALD generally incur lower healthcare costs and have fewer hospital admissions compared to those with HCC. This is likely because HCC, being a more advanced and severe condition, requires more intensive treatments, frequent monitoring, and complex interventions such as surgery, chemotherapy, or liver transplantation. In contrast, ALD management often involves lifestyle modifications, medication, and less frequent hospital visits unless it progresses to more severe stages like cirrhosis or HCC.

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, it relies on self-reported data for alcohol consumption, which may be subject to recall bias and underreporting. Secondly, the use of ICD-10 codes for diagnosing ALD and HCC might not capture all cases accurately, as some patients may be misclassified or undiagnosed. Thirdly, the study's observational design cannot establish causality between alcohol consumption and liver disease outcomes. Additionally, the cohort is based on South Korean individuals, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other populations with different drinking habits and genetic predispositions. Lastly, the data on alcohol consumption patterns and healthcare utilization may not fully reflect recent trends, as the study period ends in 2017, potentially overlooking changes in drinking behaviors and policy impacts in subsequent years.

In conclusion, our study assesses the dynamic trends in alcohol consumption in South Korea and their concerning association with ALD and related liver diseases. The gender-specific findings, particularly the heightened vulnerability of women to the adverse effects of high-risk drinking, warrant urgent public health strategies and policies tailored to these trends.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ALD:

-

Alcoholic liver disease

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- ICD-10:

-

International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision

- NHIS-HEALs:

-

National Health Insurance Service-Health Screening Cohort

- RRs:

-

Risk ratios

- SDs:

-

Standard deviations

References

Jang JY, Kim DJ. Epidemiology of alcoholic liver disease in Korea. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2018;24(2):93–9.

Yoon JH, Jun CH, Kim JH, Yoon EL, Kim BS, Song JE, Suk KT, Kim MY, Kang SH. Changing trends in liver cirrhosis etiology and severity in Korea: the increasing impact of alcohol. J Korean Med Sci. 2021;36(21):e145.

Kim LY, Yoo JJ, Chang Y, Jo H, Cho YY, Lee S, Lee DH, Jang JY, Korean Association for the Study of the L. The Epidemiology of Hepatitis B Virus Infection in Korea: 15-Year Analysis. J Korean Med Sci. 2024;39(4):e22.

Kim D, Li AA, Gadiparthi C, Khan MA, Cholankeril G, Glenn JS, Ahmed A. Changing trends in etiology-based annual mortality from chronic liver disease, from 2007 through 2016. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(4):1154–1163 e1153.

Yoon JH, Choi SK. Management of early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: challenges and strategies for optimal outcomes. J Liver Cancer. 2023;23(2):300–15.

Daher D, Dahan KSE, Singal AG. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-related hepatocellular carcinoma. J Liver Cancer. 2023;23(1):127–42.

Seitz HK, Bataller R, Cortez-Pinto H, Gao B, Gual A, Lackner C, Mathurin P, Mueller S, Szabo G, Tsukamoto H. Alcoholic liver disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4(1):16.

Korean Liver Cancer A, National Cancer Center K. 2022 KLCA-NCC Korea practice guidelines for the management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Liver Cancer. 2023;23(1):1–120.

Tang YL, Xiang XJ, Wang XY, Cubells JF, Babor TF, Hao W. Alcohol and alcohol-related harm in China: policy changes needed. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91(4):270–6.

Liangpunsakul S, Haber P, McCaughan GW. Alcoholic liver disease in Asia, Europe, and North America. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(8):1786–97.

Osna NA, Donohue TM Jr, Kharbanda KK. Alcoholic liver disease: pathogenesis and current management. Alcohol Res. 2017;38(2):147–61.

Bajaj JS, Nagy LE. Natural history of alcohol-associated liver disease: understanding the changing landscape of pathophysiology and patient care. Gastroenterology. 2022;163(4):840–51.

Ventura-Cots M, Ballester-Ferre MP, Ravi S, Bataller R. Public health policies and alcohol-related liver disease. JHEP Rep. 2019;1(5):403–13.

Lee SW. Epidemiology of alcoholic liver disease in Korea. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2020;76(2):55–9.

White AM. Gender differences in the epidemiology of alcohol use and related harms in the united states. Alcohol Res. 2020;40(2):01.

Chaiyasong S, Huckle T, Mackintosh AM, Meier P, Parry CDH, Callinan S, Viet Cuong P, Kazantseva E, Gray-Phillip G, Parker K, et al. Drinking patterns vary by gender, age and country-level income: Cross-country analysis of the International Alcohol Control Study. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2018;37 Suppl 2(Suppl Suppl 2):S53–62.

Park E, Kim YS. Gender differences in harmful use of alcohol among Korean adults. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2019;10(4):205–14.

Trends in the prevalence of high-risk drinking, during 2012-2021. Public Health Wkly Rep. 2023;16(12):376-377.

Lee S, Kim JS, Jung JG, Oh MK, Chung TH, Kim J. Korean alcohol guidelines for moderate drinking based on facial flushing. Korean J Fam Med. 2019;40(4):204–11.

Kim KH, Kang E, Yun YH. Public support for health taxes and media regulation of harmful products in South Korea. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):665.

Choi J, Choi JY, Shin A, Lee SA, Lee KM, Oh J, Park JY, Lee JK, Kang D. Trends and correlates of high-risk alcohol consumption and types of alcoholic beverages in middle-aged Korean adults: results from the HEXA-G study. J Epidemiol. 2019;29(4):125–32.

Grant BF, Chou SP, Saha TD, Pickering RP, Kerridge BT, Ruan WJ, Huang B, Jung J, Zhang H, Fan A, et al. Prevalence of 12-month alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and DSM-IV alcohol use disorder in the United States, 2001–2002 to 2012–2013: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. JAMA Psychiat. 2017;74(9):911–23.

Shmulewitz D, Aharonovich E, Witkiewitz K, Anton RF, Kranzler HR, Scodes J, Mann KF, Wall MM, Hasin D. Alcohol clinical trials I: the world health organization risk drinking levels measure of alcohol consumption: prevalence and health correlates in nationally representative surveys of U.S. adults, 2001–2002 and 2012–2013. Am J Psychiatry. 2021;178(6):548–59.

Huang DQ, Mathurin P, Cortez-Pinto H, Loomba R. Global epidemiology of alcohol-associated cirrhosis and HCC: trends, projections and risk factors. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;20(1):37–49.

Torronen J, Roumeliotis F, Samuelsson E, Kraus L, Room R. Why are young people drinking less than earlier? Identifying and specifying social mechanisms with a pragmatist approach. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;64:13–20.

Stelander LT, Hoye A, Bramness JG, Selbaek G, Lunde LH, Wynn R, Gronli OK. The changing alcohol drinking patterns among older adults show that women are closing the gender gap in more frequent drinking: the Tromso study, 1994–2016. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2021;16(1):45.

Mathurin P, Bataller R. Trends in the management and burden of alcoholic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2015;62(1 Suppl):S38–46.

Huang DQ, Terrault NA, Tacke F, Gluud LL, Arrese M, Bugianesi E, Loomba R. Global epidemiology of cirrhosis - aetiology, trends and predictions. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;20(6):388–98.

Park SH, Plank LD, Suk KT, Park YE, Lee J, Choi JH, Heo NY, Park J, Kim TO, Moon YS, et al. Trends in the prevalence of chronic liver disease in the Korean adult population, 1998–2017. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2020;26(2):209–15.

Liu Y, Sun Z, Wang Q, Wu K, Tang Z, Zhang B. Contribution of alcohol use to the global burden of cirrhosis and liver cancer from 1990 to 2019 and projections to 2044. Hepatol Int. 2023;17(4):1028–44.

McCaul ME, Roach D, Hasin DS, Weisner C, Chang G, Sinha R. Alcohol and women: a brief overview. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2019;43(5):774–9.

Mumenthaler MS, Taylor JL, O’Hara R, Yesavage JA. Gender differences in moderate drinking effects. Alcohol Res Health. 1999;23(1):55–64.

Cederbaum AI. Alcohol metabolism. Clin Liver Dis. 2012;16(4):667–85.

Ohashi K, Pimienta M, Seki E. Alcoholic liver disease: A current molecular and clinical perspective. Liver Res. 2018;2(4):161–72.

Eagon PK. Alcoholic liver injury: influence of gender and hormones. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(11):1377–84.

Kardashian A, Serper M, Terrault N, Nephew LD. Health disparities in chronic liver disease. Hepatology. 2023;77(4):1382–403.

Sedarous M, Flemming JA. Culture, stigma, and inequities creating barriers in alcohol use disorder management in alcohol-associated liver disease. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2023;21(5):130–3.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The study was supported by the Korean Association for the Study of the Liver, and it was also partly supported by the Soonchunhyang University Research Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Conceptualization: Log Young Kim, Jae Young Jang; Formal analysis: Jeong-Ju Yoo, Dong Hyeon Lee; Investigation: Young Chang, Hoongil Jo, Young Youn Cho, Sangheun Lee; Writing-original draft: Jeong-Ju Yoo, Dong Hyeon Lee; Writing-review and editing: Log Young Kim, Jae Young Jang.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Institutional Review Board of Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital approved the current study (IRB No. SCHBC 2023–05-007, approval date 23-May-2023). Informed consent was waived by the IRB since only de-identified information was utilized. Our study adhered to the ethical guidelines of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yoo, JJ., Lee, D.H., Chang, Y. et al. Trends in alcohol use and alcoholic liver disease in South Korea: a nationwide cohort study. BMC Public Health 24, 1841 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19321-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19321-z