Abstract

Background

While many populations struggle with health literacy, those who speak Spanish preferentially or exclusively, including Hispanic, immigrant, or migrant populations, may face particular barriers, as they navigate a predominantly English-language healthcare system. This population also faces greater morbidity and mortality from treatable chronic diseases, such as hypertension and diabetes. The aim of this systematic review was to describe existing health literacy interventions for patients with a Spanish-language preference and present their effectiveness.

Methods

We carried out a systematic review where Web of Science, EMBASE, and PubMed were queried using MeSH terms to identify relevant literature. Included articles described patients with a Spanish-language preference participating in interventions to improve health literacy levels in the United States. Screening and data abstraction were conducted independently and in pairs. Risk of bias assessments were conducted using validated appraisal tools.

Results

A total of 2823 studies were identified, of which 62 met our eligibility criteria. The studies took place in a variety of community and clinical settings and used varied tools for measuring health literacy. Of the interventions, 28 consisted of in-person education and 27 implemented multimedia education, with 89% of studies in each category finding significant results. The remaining seven studies featured multimodal interventions, all of which achieved significant results.

Conclusion

Successful strategies included the addition of liaison roles, such as promotores (Hispanic community health workers), and the use of multimedia fotonovelas (photo comics) with linguistic and cultural adaptations. In some cases, the external validity of the results was limited. Improving low health literacy in patients with a Spanish-language preference, a population with existing barriers to high quality of care, may help them better navigate health infrastructure and make informed decisions regarding their health.

Registration

PROSPERO (available at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021257655.t).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

While health literacy (HL) is a multifaceted concept [1, 2] almost all definitions relate HL to “the literacy and numeracy skills that enable individuals to obtain, understand, appraise, and use information to make decisions and take actions that will have an impact on health status” [3]. Low HL has been linked to poorer health outcomes, including increased mortality [4, 5]. HL has increasingly been recognized as a potentially important factor mediating health disparities, especially those related to race and ethnicity [5], and has been suggested as an important mediator of the relationship between socioeconomic status and health [6]. This may be due to communication barriers with physicians and difficulty understanding and making use of medical resources [5].

As a concept, HL has sometimes been poorly defined. A recent systematic review which sought to clarify the concept found that scholars commonly characterized HL along three main domains: knowledge of health/healthcare systems, processing and using information related to health and healthcare, and the ability to maintain health through collaboration with health providers [7]. Other theoretical frameworks developed for HL understand the concept through its effects. For example Nutbeam established a useful framework for understanding the benefits of health literacy through a “health outcomes model” in which HL is comprised of functional HL, the basic skills necessary for everyday health functioning, communicative/interactive HL, the more advanced skills needed to act independently with “motivation and self-confidence,” and critical HL, the ability to analyze and use information to “exert greater control over life events and situations” allowing people to respond adversity and to advocate for themselves [8, 9]. HL is sometimes understood as not only a skill, but an important social determinant of health, with community level and public health implications [10].

While many U.S. residents struggle with limited health literacy, there may be a particular barrier among those who speak Spanish preferentially or exclusively, including Hispanic, immigrant or migrant populations. In the United States, minority groups, immigrants, migrants, and nonnative English speakers have lower health literacy scores than White adults and are at higher risk of having poor HL, making them more susceptible to the adverse outcomes associated with low HL [11]. Hispanics are the largest group of nonnative English speakers and preferential Spanish speakers in the U.S. and have low rates of HL compared to other populations [5]. Limited English proficiency may be a factor that contributes to poorer health outcomes and reduced quality of care, especially in a predominantly English language-based health care system with a shortage of bilingual and culturally competent providers [12]. For example, one recent study found higher rates of obesity among Spanish speakers in the United States [13]. These factors, in combination with a lack of healthcare access and insurance coverage, may contribute to higher morbidity and mortality rates among Hispanics due to chronic diseases such as diabetes and obesity [14].

Methods to accommodate the HL needs of patients with a Spanish-language preference (SLP) may therefore be important in improving health equity [15]. While strides have been made in community-based educational efforts and the translation or cultural adaptation of health communication tools and processes [16], there are limited data on effective interventions to improve HL for patients with SLP in the United States [17]. The literature on interventions targeting HL in the United States has frequently grouped together populations of immigrants who do not share a common language [18] or, conversely, focused only on individuals from a single nationality [19, 20]. Given the gap in the literature synthesizing research on HL interventions for patients with SLP in the United States and the important association between HL and health outcomes, we conducted a systematic review of the literature that summarizes and evaluates the effectiveness of HL intervention strategies for patients with SLP in the United States. The aim of this systematic review was to describe existing HL interventions for patients with SLP and present their reported effectiveness.

Methods

Protocol and registration

The protocol for this review was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42021257655). The use of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) enabled authors to follow best practices in conducting the review [21].

Search strategy and screening

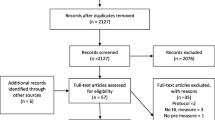

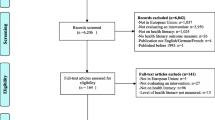

Searches were conducted in the PubMed, MEDLINE, Web of Science, and Embase databases and data was extracted from these databases between January 20, 2020 and April 27, 2023 (Fig. 1.). The keywords for each database included: “health literacy” and “intervention” or “Spanish”, “Hispanic” or “LEP,” or “limited English proficiency.” Databases were queried to include only articles published between January 1, 2011 and April 27, 2023. In 2010, the U.S. The Department of Health and Human Services unveiled the National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy, bringing more attention to this matter and inspiring more research on HL. Our review also avoids redundancy with a 2011 comprehensive review [5], which found no interventions focused on HL in Spanish-speaking populations, with only three mentioned measures of HL in this population.

After removing duplicates, two reviewers, P.P. and L.D., independently reviewed titles and abstracts to select potentially eligible articles based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria described below. Any disagreements regarding the inclusion of a study were resolved by a third reviewer, J.H. Bibliographies of included studies were subsequently hand searched.

Inclusion & exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria for this literature review included articles that a) featured participants with SLP, b) described interventions that occurred in the United States, c) described interventions that were designed to mitigate the effects of low HL in participants with SLP and improve the use of health services or the health outcomes in these populations, d) were shared in an online format in indexed scientific journals, e) were written in English or Spanish, f) were published in 2011–2023, g) were randomized control trials (RCTs), pre/post (PP) studies, prospective cohort (PC) studies, cross-sectional (CC) studies, or mixed methods studies and h) measured effectiveness of intervention using HL assessment tools or health outcomes.

Exclusion criteria included studies of outcomes related to numeracy or literacy alone without reference to HL because such interventions were found to differ from those that dealt with these issues in the context of HL. We also excluded studies that did not report HL interventions targeting Spanish-speakers in the United States.

Assessment of methodology quality

We assessed the methodological quality of each included study using the Revised Tool to Assess Risk of Bias in Randomized Trials (RoB 2) [22] and the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies—of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool for assessing risk of bias in the different interventions analyzed (RCTs, PP studies, PC studies, CC studies, and mixed methods studies) [23]. Two review authors (P.P. and L.D.) independently performed quality assessments. Disagreements regarding the overall assessments were resolved through discussion, with a third reviewer as the final arbitrator (J.H.). Bibliographies of included studies were subsequently hand searched.

Data synthesis

After piloting, four reviewers (J.H., L.A., P.P., L.D.) conducted data extraction using a standardized data extraction template (Appendix 1). Due to the heterogeneity of interventions, outcomes assessed, and varying durations of interventions, we did not pool the data and instead conducted a narrative analysis. We conducted a thematic analysis of identified studies and grouped studies for synthesis on the basis of identified categories. This process consisted of iterative discussions of the studies by all members of the study team and was based on published guidelines for Synthesis without Metanalysis (SWiM) [24]. Our data synthesis specifically grouped studies based on the categories of study characteristics, measures of effectiveness, reported effectiveness by intervention type, and quality assessment. We stratified the results by intervention type. While we did not focus on migrant status specifically, this could be estimated by one of our data extraction items, country of origin.

Results

Study characteristics

After removal of duplicates, 2,823 titles and abstracts were screened for inclusion using the criteria described above. A manual search of bibliographies yielded eight additional articles for screening. A total of 121 potentially relevant articles were selected using the inclusion criteria described above. After a detailed full-text analysis of each study, 62 studies were included, and 59 were excluded, as indicated in Fig. 1. This included 17 RCTs, 35 PP studies, 3 PC studies, 3 CC studies, and 4 mixed methods studies. A summary of the study characteristics can be found in Table 1, 2, and 3. The studies encompassed mainly female, middle-aged adults (range: 30 to 50); only two studies included participants under the age of 18 [25, 26] and no studies were focused solely on pediatric populations. Only a minority of participants had graduated from college. Sample sizes varied from 10 to 943. Interventions included in-person education (n = 28), multimedia education (n = 27) and other types of multimodal strategies (n = 7). Eighteen studies made use of lay health advisors and promotores.

Topics included prenatal care and parent education; breast, cervical, colorectal, and ovarian cancer; diet and healthy lifestyle choices; mental health literacy; diabetes; cardiovascular disease; end-stage renal disease; asthma; upper respiratory infections; inflammatory bowel disease; HIV/AIDS; skin care; hearing loss prevention; medication understanding; palliative care; family health history; chronic pain; healthcare navigation; and anesthesia education. Thirty-four studies employed a theoretical framework when designing and conducting research, and there was little heterogeneity in terms of frameworks employed. No framework was shared by more than four studies.

Studies were performed in a variety of settings, including clinics (n = 13), hospitals and health centers (n = 13), Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) or safety net clinics (n = 9) and community spaces (n = 18). Common community settings, which include community health centers and safety net clinics, frequently used curricular interventions embedded in educational curricula and educational workshops (n = 18). Larger hospital networks implemented organizational interventions, often updating their practices or replacing standard-of-care materials with language and culturally concordant materials (n = 8).

Measures of effectiveness

The measures of successful enhancement of HL used by the studies in our review were heterogenous, and were often unvalidated measures of knowledge or beliefs. Twenty-two studies had a questionnaire about beliefs, knowledge or practice that was developed by the researchers, limiting the validity of their results. Fifty-eight studies measured effectiveness quantitatively, and four were mixed methods. The two most common approaches to primary outcomes were either HL assessment tools [16, 17, 25, 25, 26, 28, 30,31,32, 34,35,36,37,38, 41, 47, 49, 50, 53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61, 63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72, 74,75,76, 78,79,80,81,82,83] (n = 45) or health outcomes [27, 29, 39, 42, 48, 51, 52] (n = 7), with some studies using both [15, 43, 46, 84,85,86,87,88,89,90] (n = 10). HL tools most commonly took the form of pretest/posttest questionnaires specifically developed by the researchers to assess knowledge gained over the course of a given intervention. A few studies (n = 10) utilized previously validated disease-specific assessments of HL, such as the High Blood Pressure-Health Literacy Scale for high blood pressure [32], or more standardized Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA) [31, 37, 38, 49, 50, 52, 55, 60, 68, 73] (n = 10) and/or Newest Vital Sign (NVS) [28, 43, 51, 52, 68, 76] (n = 6), to assess overall changes based on the participant’s ability to read and understand generic health-related materials.

Other outcome measures included patient satisfaction and patient attitude surveys, which were intended to predict not only knowledge of health conditions but also attitudes toward receiving treatment [84]. Higher satisfaction and improved attitude scores were thought to lead to a more positive and confident approach in obtaining healthcare. Some studies measured improvements in confidence and self-advocacy [31, 34, 70]. Medical health measurements and outcomes, such as blood pressure readings, were also commonly used as primary outcomes [27, 46, 48, 74]. Secondary measures were also varied and included measures of patient confidence, perceived support, perceived barriers to care, level of comfort, and adherence to the intervention.

Studies also varied in how they measured the long-term changes associated with their interventions. Thirty-one studies had a follow up of at least a month, ranging from 1 to 24 months, with most studies doing a 1 month follow up (n = 7) or a 3 month follow up (n = 8).

Overview of health literacy interventions

In-Person Education

In-person education health literacy programs varied in presentation of material but shared commonalities of repeated meetings in a class setting that encouraged practice and facilitated opportunities for enhanced participant engagement compared to other modalities (Table 1). A study by Cruz [30], found the use of 90 min training session conducted by promotores focusing on general knowledge for diabetes, risk factors, and prevention and control of diabetes provided significant improvement on diabetes knowledge for diabetic participants comparing pre- and posttest scores (13.7 vs. 18.6, p < 0.001; Cohen’s d = 1.2), and for nondiabetic participants (12.9 vs. 18.2, p < 0.001; Cohen’s d = 1.2).

Similarly, Buckley [27] assessed the implementation of social clubs hosted by navegantes (patient navigators) for 2 h every week over 5 weeks. The findings suggested 88.9% of 126 participants increased health literacy and over 60% decreased at least one risk factor associated with metabolic syndrome. Change for those that improved, [mean (SD)]: Weight [− 6.0 lbs (5.2)]; BMI [− 1.1 (1.0)]; Waist Circumference [− 2.2 inches (1.5)]; Blood Glucose [− 26.3 mg/dl (27.5)]; LDL Cholesterol [− 19.1 mg/dl (16.8)]; Systolic BP [− 11.1 mmHg (9.5)]; Health Literacy Test (n = 117) [+ 22.2% (19.7%)]. Castaneda [28] studied the implementation of 6-week, culturally tailored, promotora-based group for health prevention knowledge and found participants improved their self-reported cancer screening, breast cancer knowledge (Mpre = 2.64, Mpost = 3.02), daily fruit and vegetable intake, and ability to read a nutrition label (p < 0.05).

Across all the different in-person education there were common findings that repeated exposure to health education information in an engaging classroom setting provided meaningful improvements to health literacy in SLP populations that correlated with improvements in physical health and greater utilization of health screening services.

Multimedia education

Multimedia approaches to health literacy education varied from narrative films and fotonovelas to animated culturally sensitive videos and virtual workshops to assess applied knowledge (Table 2). The commonality shared with these interventions were that they could largely be independently navigated without need for transportation or cost to the participant as long as they had access to a computer and the internet.

A study related to health literacy in women’s health, Borrayo [53] found that through a 8-min narrative film to reinforce desired self-efficacy and behavioral intentions as precursors to engaging in mammography screening there was a significant increase in breast cancer knowledge ( Wilks’s Λ = 0.75, F(1, 39) = 13.15, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.25) and mammography self-efficacy ( Wilks’s Λ = 0.76, F(1, 37) = 11.64, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.24) compared to baseline and control group. Furthermore, Cabassa [54] assessed the use of a fotonovela centered around entertainment-education intervention toward mental health stigma finding a significant increase in depression treatment knowledge scores at posttest ( B = 1.22, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.91) and 1-month follow-up ( B = 0.81, p < 0.01, Cohen’s d = 0.53). Calderon [55] looked at the implementation of an animated, culturally sensitive, Spanish video to improve diabetes health literacy (DHL). The findings reported DHL survey scores improved significantly more in the experimental group than the control group (adjusted mean = 55% vs 53%, F = 4.7, df = 1, p = 0.03). Additionally, Cheney [56] studied the application of tailor MyPlate recipes to local food sources and culture, virtual cooking demonstrations, and Spanish cookbook, on diabetes education finding there was an increased confidence in adherence to two of four components of the Mediterranean diet (badded sugar = 0.24; 95%CI: 0.02, 0.46; bredmeat = 0.5; 95% CI: 0.02, 0.98).

Other types of multimodal strategies

Multimodal strategies provided a crossover between in-person and multi-media focused health literacy approaches (Table 3). A study by Auger [15], found the use of fotonovelas as an educational tool along with health education facilitation by the teacher and lay health educator provided an increased knowledge of pregnancy, childbirth, and breastfeeding (p < 0.001) and confidence in navigating pregnancy, caring for oneself and the baby, and interacting with health professionals (p ≤ 0.05).

Additionally, Calderon [78] took a multimodal approach to mental health education via workshops including a short video on possible psychotic and depressive symptoms, La CLAve mnemonic device to describe the main symptoms of psychosis, and a narrative film to discuss its portrayal of symptoms. That study demonstrated a significant increase in psychotic symptoms reported as definition of serious mental illness (pre, M = 0.69, SD = 0.61; post, M = 1.23, SD = 0.90, t(80) = − 5.64; p < 0.001; Cohen's d = 0.70) and ability to detect a serious mental illness in others (pretraining: M = 2.83, SD = 1.31; posttraining: M = 3.24, SD = 1.27, t(74) = − 2.76, p < 0.05; Cohen's d = 0.32), and decrease in participants' recommendations for nonprofessional help-seeking (pre: 49.4%, post: 25.9%, N = 81, p = 0.001). There was no significant change in recommendations for professional help (pre: 64.2%, post: 72.8%, N = 81, p = 0.25).

Reported effectiveness by intervention type

Of the interventions, 89% of in-person educational interventions (n = 25) and 89% of multimedia educational interventions (n = 24) found improvements to HL. All multimodal interventions (n = 7) provided improvements in HL. The use of lay health advisors and promotores was correlated with increased effectiveness; all 18 studies that used this technique reported that their interventions had caused statistically significant changes in HL [27, 28, 34, 46, 70]. Similarly, all nine of the studies implementing fotonovela strategies reported statistically significant improvements in HL [16, 25, 53, 54, 61, 63, 74].

Quality assessment

The risk of bias assessment for RCTs evaluated risks due to randomization, outcomes, and result reporting (Table 4). Among RCTs (n = 17), one was assessed as having a high risk of bias, and eight were assessed as having some concerns. Non-RCTs were likewise evaluated for risk of bias due to problems with recruitment, confounding factors, missing data, and selective measurement of outcome or result reporting (Table 5). Among non-RCTs (n = 36), 14 studies had a serious risk of bias, while the remaining 22 studies had a moderate risk of bias.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this review is the first to systematically describe and evaluate the effectiveness of HL interventions among patients with SLP in the United States. Recent reviews have studied the impact of different intervention strategies for increasing the HL of the general population [85] and for immigrant communities [18] but have not focused on Spanish speakers – a community largely at risk for low HL and poor health outcomes [5, 11, 17].

Our review found that, as with other populations with a non-English language preference, including migrant populations [86], there is a lack of evidence-based specific interventions to raise HL tailored to U.S. patients with SLP. Further, our review found that the few existing studies may be at risk of bias. The high risk of bias we found especially in non-RCTs on this topic likely represents both the lack of attention to research addressing this need in SLP populations, as well as difficulties inherent in testing and measuring interventions aimed at improving HL more broadly. Our review of quality was in line with other reviews on this topic [18, 87] which found that a risk of bias was introduced primarily due to difficulty blinding participants and moderators due to the nature of study designs. This made RCTs more difficult to conduct, and as a result, studies primarily used pretest/posttest and cross-sectional methodologies. This finding points not only to a need for high-quality studies of HL in this population, but also for the potential to critically rethink how to conduct research on HL in a high-quality, low risk of bias way. Additionally, studies reported sample sizes ranging from 10 to 943 participants, which made it difficult to compare effect sizes directly. This variation likely reflects the dissimilarity of study designs, sample populations and setting types, thus making it difficult to compare across studies, a challenge that has been previously acknowledged for reviews of HL.

There are also significant differences in patient populations across reviews, and many studies had a low number of participants. This small sample size was in some cases due to strict study inclusion criteria, and other cases were due to high rates of attrition. This could be partly due to primarily targeting participants already facing cultural, socioeconomic, and educational barriers, making them more difficult to recruit and retain in research. Many studies have indicated that their sample may not be representative due to sampling methodologies or that there may be limited generalizability of results. This was due in part to convenience sampling or small sample sizes, which made it difficult to determine whether findings represented a true effect due to limitations in statistical power.

Some studies were focused on only one research site and/or a highly specific Hispanic immigrant community with a SLP (i.e., Mexican immigrants [52]), limiting generalizability. At the same time, while we attempted to capture the difference between the broader category of Spanish speaking populations in the United States and specific migrant populations, most studies did not include this sort of information, indicating a potential need for studies that focus on specific SLP migrant communities. No studies addressed pediatric populations. Another factor limiting the generalizability of the reviewed studies was that the majority of study participants were women; this may be tied to a wider lack of healthcare utilization among Hispanic men, including those with a SLP [88,89,90]. The relative paucity of males in the sample population of the studies may indicate a need for research that focuses on men with a SLP. To date, only a few strategies have been developed to include males with a SLP in research, including the use of male community health workers and health outreach in workplaces and providing public transportation [41]. Finally, the studies reviewed included a predominantly adult to middle-aged population (aged 30–50) rather than older adults who are more at risk for serious medical problems. This suggests that several important populations (men, children, older adults) may be missed by most previous HL interventions in populations with SLP.

The varied, poorly standardized, heterogenous measures used to assess HL in reviewed studies demonstrate that HL as a concept is poorly defined by researchers, and the concept likely encompasses more than can be quantified by numeric scores on standardized assessments of knowledge. For example, in assessing HL, there may also be a need to address the ability of patients to advocate for themselves, ask questions, and feel empowered to change their health behaviors [8, 9, 16, 74, 85]. Existing measures of HL may not fully capture HL concepts, and thus may be a poor proxy of effectiveness. Studies in our review often used measures that were not validated and tested knowledge on a specific health topic or reported beliefs about health as proxies for HL, and relatively few measured direct behavioral changes, attempts at communication self-efficacy or advocacy, or effects on health outcomes. A key takeaway of this review is the need to critically reexamine definitions and measures of HL, and to develop and validate improved qualitative and quantitative measures of HL outcomes. Only about half of the studies used a theoretical framework to inform their intervention or research, and studies rarely employed the same frameworks, perhaps partially accounting for the variety of measures and the limitations in the ways that HL was framed by researchers.

We found that studies of HL among people with SLP in the United States therefore followed trends within the literature, in which HL is measured through knowledge of health/healthcare systems; to a lesser extent, studies included in our review also attempted to measure participants’ use of information related to health and healthcare, and their ability to maintain health through collaboration with health providers [7]. When framed in terms of Nutbeam’s health outcomes approach, the studies mostly attempted to measure functional HL, occasionally addressed communicative/interactive HL, and rarely attempted to address critical HL [8, 9]. This focus on HL as knowledge rather than personal health advocacy has important ramifications in terms of the skills that HL interventions focus on building, and may help to explain the success and failure of HL interventions.

In addition to the importance of improving individual’s health literacy there is support in the literature to improve “organizational health literacy.” Organizational health literacy refers to the responsibility for health care systems to address populations with low health literacy [91]. Methods for organizations to address populations with low health literacy include “reducing the complexity of health care; increasing patient understanding of health information and enhancing supports for patients of all levels of health literacy” [91]. Because limited health literacy has been associated with increased cost of healthcare organizations have an incentive to address health literacy. However, few if any of the studies attempted to address organizational health literacy, and placed the onus for building HL on the individual patient and their family.

Specific recommendations

Successful interventions focused on HL interventions that targeted SLP populations through linguistically and culturally concordant techniques that utilized community member liaisons and culturally relevant storytelling. Successful interventions were also often well integrated within communities and organizations.

Our review found that interventions utilizing cultural and linguistic concordance (ie. Spanish-language, culturally salient concepts/terms), liaison roles (promotores), and narrative media were effective in achieving notable improvements in HL among patients with SLP. These interventions focused more on what Nutbeam frames as communicative/interactive HL [8, 9]. The relative success of these interventions may be due to more effective communication with patients through a shared cultural background and deeper levels of trust. One particularly effective strategy is the use of narrative in media, as seen with fotonovela strategies [16, 25, 53, 54, 61, 63, 74]. Such strategies may involve a video or booklet presenting important health information in a story format. Narrative media appeared to activate study participants and lead to improvements in health knowledge and behavior change. Another important element of effective multimedia health interventions is cultural adaptation to address previously identified cultural concepts such as respeto, familismo, marianismo, and personalismo [16, 25, 55, 62, 65, 68, 73, 76]. Realistic stories with Spanish-speaking characters and culturally tailored information were key components of these interventions [25, 54, 55, 74]. Prior research has shown that identification with storytellers is an important prerequisite for patient engagement and is particularly useful in combating cultural stigma and eliciting behavioral health changes [92].

Liaison roles that employ educators and health promoters from similar cultural backgrounds as patients were also an important strategy used by reviewed studies. The lived experience and cultural understanding from these workers (promotores, navegantes, community health workers) may help boost patient comprehension and overcome distrust of the healthcare system [93]. Linguistic and culturally concordant care, including cultural competency training for providers, has also repeatedly been identified as a successful strategy for increasing HL among immigrant populations generally [18]. Furthermore, successful interventions often consider the opinions of the target population when designing content to ensure that the experience is culturally relevant [16, 28, 29, 34, 35, 40, 44, 45, 55, 62, 65, 73, 76].

Our review also included a number of multimedia intervention strategies (n = 22) that might be utilized more often in the future following the increased acceptance of online options since the COVID-19 pandemic. Interestingly, of the 14 studies published since 2020, seven were multimedia interventions. Our search also revealed the importance of including nonmedical settings such as community gathering spaces, which may serve as a hub for creating a wider network of health promotion. The integration of health promotion interventions into communities may be complimentary to the long-term reinforcement of health education, serving as a means of achieving sustained outcomes.

Other elements of successful HL interventions may include finding a fit between factors such as intervention type, size and type of setting, duration of time available, and level of community integration (Fig. 2). As described above, HL may be framed as organizational as well as individual, and successful interventions better integrate organizational setting into the structure of the HL intervention. We refer to community integration as the level of incorporation of community resources, stakeholders such as promotores, and settings into interventions aimed at improving health literacy, concepts drawn from the literature [94, 95]. These categories of community integration were inferred from the setting type since we expect large hospitals to be less involved in community initiatives than community clinics or community settings (i.e. local churches) themselves. Smaller, community-based settings and nonmedical centers such as churches and college campuses seemed to be more successful with implementing multiweek curricula interventions. This may be because these settings have the infrastructure in place for recruitment and retention of community members with a SLP. Larger hospital systems and clinics with less time and resources available may be better able to focus on culturally and linguistically concordant patient materials and replace standard of care materials written in English with multimedia health information. These recommendations are illustrated in Fig. 2, which displays fit between intervention type and setting.

The findings of our review are also relevant to studies of HL in other populations with a non-English preference, including minority, migrant or immigrant populations. Previous reviews of HL interventions did not include studies measuring HL indirectly through variables such as health outcomes or behavioral change but only included those using standardized tools [85]. However, as these standardized assessment tools are available predominantly in English, this approach may limit the generalizability of past reviews to non-English speaking populations. A growing body of evidence suggests that a reframing of our understanding of HL, especially among marginalized communities, is necessary to improve health equity [2].

Finally, our review highlights a need for additional attention to the development and adaptation of HL interventions for patients with SLP in the United States. Policies promoting HL interventions may need to better address the needs of specific populations through research and the widespread promotion of effective strategies.

Limitations

A limitation of our review is that all studies were conducted in the United States, which limits the generalizability of our findings to healthcare systems in other countries. It should be noted that we did not explore gray literature. We also chose to limit our review to studies that took place after 2010, preventing a fuller historical examination of HL literature. Finally, we could not conduct a meta-analysis due to variability in design and measurement.

Conclusion

There is a small but growing body of literature that addresses the need for HL interventions among individuals in the United States with SLP. However, there is no consensus around strategies to improve or tools to assess HL, and studies vary greatly in quality and risk of bias. Important target populations, such as children, older adults and men, may be excluded from this research. Strategies that incorporate linguistic and cultural factors particular to this population, such as fotonovelas and health promoters from similar cultural backgrounds, may be of use in promoting HL. There is a need for improved research and policy on HL interventions specifically targeting this population.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- HL:

-

Health literacy

- SLP:

-

Spanish-language preference

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

- RCTs:

-

Randomized control trials

- PP:

-

Pre/post

- PC:

-

Prospective cohort

- CC:

-

Cross-sectional

- RoB 2:

-

Revised Tool to Assess Risk of Bias in Randomized Trials

- ROBINS -I:

-

Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies - of Interventions

- SWiM:

-

Synthesis without Metanalysis

- FQHCs:

-

Federally Qualified Health Centers

- TOFHLA:

-

Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults

- NVS:

-

Newest Vital Sign

- DHL:

-

Diabetes health literacy

- SP:

-

Spanish-speaking

- ES:

-

English-speaking

- TT:

-

Tummy time

- UC:

-

Usual Care

- IC:

-

Intervention Care

- PA:

-

Physical activity

- EHS:

-

Early Head Start

- KAP:

-

Knowledge, Attitudes, Perception

- PED:

-

Pediatric Emergency Department

- ECHO:

-

Empowering Change in Health Outcomes

- H-SCALE:

-

Hypertension Self-Care Activity Level Effects

- ADDIE:

-

Analysis, Design, Develop, Implement, and Evaluate

- PaCKS:

-

Palliative Care Knowledge Scale

- ESRD:

-

End-stage renal disease

- D-Lit:

-

Depression Literacy Questionnaire

- DSS:

-

Depression Stigma Scale

- ATSPPH-SF:

-

Attitudes Towards Seeking Professional Psychological Help Short Form

- EPPM:

-

Extended Parallel Process Model

- HPD:

-

Hearing protection devices

- PHM:

-

Preventive health model

- REALM-SF:

-

Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine—Short Form

- PHQ-9:

-

9-item Patient Health Questionnaire

- DKM:

-

Depression Knowledge Measure

- VAS:

-

Visual analog scale

- PDSA:

-

Plan, Do, Study, Act

- MUQ:

-

Medication Understanding Questionnaire

References

Baker DW. The meaning and the measure of health literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:878–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00540.x.

Bahrambeygi F, Rakhshanderou S, Ramezankhani A, Ghaffari M. Hospital health literacy conceptual explanation: a qualitative content analysis based on experts and population perspectives. J Educ Health Promot. 2023;12:31. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_494_22.

Paasche-Orlow MK, Wolf MS. Promoting health literacy research to reduce health disparities. J Health Commun. 2010;15(Suppl 2):34–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2010.499994.

Fan Z, Yang Y, Zhang F. Association between health literacy and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Public Health. 2021;79:119. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-021-00648-7.

Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:97–107. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005.

Stormacq C, Van den Broucke S, Wosinski J. Does health literacy mediate the relationship between socioeconomic status and health disparities? Integrative review Health Promot Int. 2019;34:e1–17. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/day062.

Liu C, Wang D, Liu C, Jiang J, Wang X, Chen H, et al. What is the meaning of health literacy? A systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Fam Med Community Health. 2020;8:e000351. https://doi.org/10.1136/fmch-2020-000351.

Nutbeam D. Health literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot Int. 2000;15:259–67. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/15.3.259.

Sørensen K, Van den Broucke S, Fullam J, Doyle G, Pelikan J, Slonska Z, et al. Health literacy and public health: a systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:80. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-80.

Nutbeam D, Lloyd JE. Understanding and responding to health literacy as a social determinant of health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2021;42:159–73. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-102529.

Kunter M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, The PC, Literacy H, of America’s adults: results from the,. national assessment of adult literacy. US Dep Educ NCES. 2003;2006–483(2006):76.

Sentell T, Braun KL. Low health literacy, limited English proficiency, and health status in Asians, Latinos, and other racial/ethnic groups in California. J Health Commun. 2012;17(Suppl 3):82–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2012.712621.

Livingston G, Minushkin S, Cohn D. Hispanics and Health Care in the United States. Pew Research Center. 2008.

Alemán JO, Almandoz JP, Frias JP, Galindo RJ. Obesity among Latinx people in the United States: a review. Obes Silver Spring Md. 2023;31:329–37. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.23638.

Auger SJ, Verbiest S, Spickard JV, Simán FM, Colindres M. Participatory group prenatal education using photonovels: evaluation of a lay health educator model with low-income Latinas. J Particip Med. 2015;7:e13.

Ochoa CY, Murphy ST, Frank LB, Baezconde-Garbanati LA. Using a culturally tailored narrative to increase cervical cancer detection among Spanish-speaking Mexican-American women. J Cancer Educ Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ. 2020;35:736–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-019-01521-6.

Mas FS, Ji M, Fuentes BO, Tinajero J. The health literacy and ESL study: a community-based intervention for Spanish-speaking adults. J Health Commun. 2015;20:369–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2014.965368.

Fernández-Gutiérrez M, Bas-Sarmiento P, Albar-Marín M j, Paloma-Castro O, Romero-Sánchez J m. Health literacy interventions for immigrant populations: a systematic review. Int Nurs Rev. 2018;65:54–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12373.

Chen Y, Ran X, Chen Y, Jiang K. Effects of health literacy intervention on health literacy level and glucolipid metabolism of diabetic patients in Mainland China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Diabetes Res. 2021;2021:1503446. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/1503446.

Flores BE, Acton G, Arevalo-Flechas L, Gill S, Mackert M. Health literacy and cervical cancer screening among Mexican-American Women. Health Lit Res Pract. 2019;3:e1–8. https://doi.org/10.3928/24748307-20181127-01.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372: n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366: l4898. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4898.

Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355: i4919. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i4919.

Campbell M, McKenzie JE, Sowden A, Katikireddi SV, Brennan SE, Ellis S, et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. BMJ. 2020;368: l6890. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l6890.

Unger JB, Cabassa LJ, Molina GB, Contreras S, Baron M. Evaluation of a fotonovela to increase depression knowledge and reduce stigma among hispanic adults. J Immigr Minor Health Cent Minor Public Health. 2013;15:398–406. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-012-9623-5.

Schlumbrecht M, Yarian R, Salmon K, Niven C, Singh D. Targeted ovarian cancer education for Hispanic Women: a pilot program in Arizona. J Community Health. 2016;41:619–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-015-0137-7.

Buckley J, Yekta S, Joseph V, Johnson H, Oliverio S, De Groot AS. Vida Sana: a lifestyle intervention for uninsured, predominantly Spanish-speaking immigrants improves metabolic syndrome indicators. J Community Health. 2015;40:116–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-014-9905-z.

Castañeda SF, Giacinto RE, Medeiros EA, Brongiel I, Cardona O, Perez P, et al. Academic-community partnership to develop a patient-centered breast cancer risk reduction program for latina primary care patients. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2016;3:189–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-015-0125-8.

Chen HW, Limmer EE, Joseph AK, Kinser K, Trevino A, Valencia A, et al. Efficacy of a lay community health worker (promotoras de salud) program to improve adherence to emollients in Spanish-speaking Latin American pediatric patients in the United States with atopic dermatitis: a randomized, controlled, evaluator-blinded study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2022;40:69–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/pde.15148.

Cruz Y, Hernandez-Lane M-E, Cohello JI, Bautista CT. The effectiveness of a community health program in improving diabetes knowledge in the Hispanic population: Salud y Bienestar (Health and Wellness). J Community Health. 2013;38:1124–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-013-9722-9.

Howie-Esquivel J, Bibbins-Domingo K, Clark R, Evangelista L, Dracup K. A culturally appropriate educational intervention can improve self-care in Hispanic patients with heart failure: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Cardiol Res. 2014;5:91–100. https://doi.org/10.14740/cr346w.

Han H-R, Delva S, Greeno RV, Negoita S, Cajita M, Will W. A Health literacy-focused intervention for Latinos with hypertension. Health Lit Res Pract. 2018;2:e21–5. https://doi.org/10.3928/24748307-20180108-02.

Jandorf L, Ellison J, Shelton R, Thélémaque L, Castillo A, Mendez EI, et al. Esperanza y Vida: a culturally and linguistically customized breast and cervical education program for diverse latinas at three different United States sites. J Health Commun. 2012;17:160–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2011.585695.

Kaphingst KA, Lachance CR, Gepp A, Hoyt D’Anna L, Rios-Ellis B. Educating underserved Latino communities about family health history using lay health advisors. Public Health Genomics. 2011;14:211–21. https://doi.org/10.1159/000272456.

Laughman AB, Boselli D, Love M, Steuerwald N, Symanowski J, Blackley K, et al. Outcomes of a structured education intervention for Latinas concerning breast cancer and mammography. Health Educ J. 2017;76:442–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0017896917691789.

Martin M, Garcia M, Christofferson M, Bensen R, Yeh A, Park K. Spanish and english language symposia to enhance activation in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;63:508–11. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0000000000001191.

Soto Mas F, Jacobson HE, Olivárez A. Adult education and the health literacy of hispanic immigrants in the United States. J Lat Educ. 2017;16:314–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348431.2016.1247707.

Mas FS, Schmitt CL, Jacobson HE, Myers OB. A cardiovascular health intervention for Spanish speakers: the health literacy and ESL curriculum. J Community Health. 2018;43:717–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-018-0475-3.

Mojica CM, Morales-Campos DY, Carmona CM, Ouyang Y, Liang Y. Breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer education and navigation: results of a community health worker intervention. Health Promot Pract. 2016;17:353–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839915603362.

Moralez EA, Rao SP, Livaudais JC, Thompson B. Improving knowledge and screening for colorectal cancer among hispanics: overcoming barriers through a promotora-led home-based educational intervention. J Cancer Educ Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ. 2012;27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-012-0357–9.

Nitsos A, Estrada RD, Hilfinger Messias DK. Tummy time for Latinos with limited english proficiency: evaluating the feasibility of a cultural and linguistically adapted parent education intervention. J Pediatr Nurs. 2017;36:31–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2017.04.004.

Ockene IS, Tellez TL, Rosal MC, Reed GW, Mordes J, Merriam PA, et al. Outcomes of a Latino Community-based intervention for the prevention of diabetes: the lawrence Latino diabetes prevention project. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:336–42. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300357.

Otilingam PG, Gatz M, Tello E, Escobar AJ, Goldstein A, Torres M, et al. Buenos hábitos alimenticios para una buena salud: evaluation of a nutrition education program to improve heart health and brain health in Latinas. J Aging Health. 2015;27:177–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264314549660.

Peña-Purcell NC, Boggess MM. An application of a diabetes knowledge scale for low-literate Hispanic/Latinos. Health Promot Pract. 2014;15:252–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839912474006.

Rascón MS, Garcia ML, Nguyen-Rodriguez ST, Galvez G, Gepp A, Carrillo E, et al. Comprando Rico y Sano: increasing latino nutrition knowledge, healthful diets, and food access through a national community-based intervention. Am J Health Promot. 2022;36:876–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/08901171211073956.

Risica PM, McCarthy ML, Barry KL, Oliverio SP, Gans KM, De Groot AS. Clinical outcomes of a community clinic-based lifestyle change program for prevention and management of metabolic syndrome: results of the ‘Vida Sana/Healthy Life’ program. PLoS ONE. 2021;16: e0248473. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248473.

Romero DC, Sauris A, Rodriguez F, Delgado D, Reddy A, Foody JM. Vivir Con Un Corazón Saludable: a community-based educational program aimed at increasing cardiovascular health knowledge in high-risk Hispanic Women. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2016;3:99–107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-015-0119-6.

Sanchez JI, Briant KJ, Wu-Georges S, Gonzalez V, Galvan A, Cole S, et al. Eat healthy, be active community workshops implemented with rural hispanic women. BMC Womens Health. 2021;21:24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-020-01157-5.

Soto Mas F, Cordova C, Murrietta A, Jacobson HE, Ronquillo F, Helitzer D. A multisite community-based health literacy intervention for Spanish speakers. J Community Health. 2015;40:431–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-014-9953-4.

Stockwell MS, Catallozzi M, Meyer D, Rodriguez C, Martinez E, Larson E. Improving care of upper respiratory infections among Latino early head start parents. J Immigr Minor Health. 2010;12:925–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-010-9326-8.

Stockwell MS, Catallozzi M, Larson E, Rodriguez C, Subramony A, Andres Martinez R, et al. al. Effect of a URI-related educational intervention in early head start on ED visits. Pediatrics. 2014;133:e1233–40. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-2350.

Warren-Findlow J, Coffman MJ, Thomas EV, Krinner LM. ECHO: a pilot health literacy intervention to improve hypertension self-care. HLRP Health Lit Res Pract. 2019;3:e259–67. https://doi.org/10.3928/24748307-20191028-01.

Borrayo EA, Rosales M, Gonzalez P. Entertainment-education narrative versus nonnarrative interventions to educate and motivate latinas to engage in mammography screening. Health Educ Behav Off Publ Soc Public Health Educ. 2017;44:394–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198116665624.

Cabassa LJ, Oh H, Humensky JL, Unger JB, Molina GB, Baron M. Comparing the impact on latinos of a depression brochure and an entertainment-education depression fotonovela. Psychiatr Serv Wash DC. 2015;66:313–6. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201400146.

Calderón JL, Shaheen M, Hays RD, Fleming ES, Norris KC, Baker RS. Improving diabetes health literacy by animation. Diabetes Educ. 2014;40:361–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145721714527518.

Cheney AM, McCarthy WJ, Pozar M, Reaves C, Ortiz G, Lopez D, et al. “Ancestral recipes”: a mixed-methods analysis of MyPlate-based recipe dissemination for Latinos in rural communities. BMC Public Health. 2023;23:216. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14804-3.

Enguidanos S, Storms AD, Lomeli S, van Zyl C. Improving palliative care knowledge among hospitalized hispanic patients: a pilot study. J Palliat Med. 2022;25:1179–85. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2021.0559.

Forster M, Allem J-P, Mendez N, Qazi Y, Unger JB. Evaluation of a telenovela designed to improve knowledge and behavioral intentions among Hispanic patients with end-stage renal disease in Southern California. Ethn Health. 2016;21:58–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2015.1007119.

Gonzalez F, Benuto LT. ¡Yo no Estoy Loca! A behavioral health telenovela style entertainment education video: increasing mental health literacy among Latinas. Community Ment Health J. 2022;58:850–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-021-00892-9.

Gossey JT, Whitney SN, Crouch MA, Jibaja-Weiss ML, Zhang H, Volk RJ. Promoting knowledge of statins in patients with low health literacy using an audio booklet. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2011;5:397–403. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S19995.

Guiberson M, Wakefield E. A preliminary study of a Spanish graphic novella targeting hearing loss prevention. Am J Audiol. 2017;26:259–67. https://doi.org/10.1044/2017_AJA-16-0069.

Gwede CK, Sutton SK, Chavarria EA, Gutierrez L, Abdulla R, Christy SM, et al. A culturally and linguistically salient pilot intervention to promote colorectal cancer screening among Latinos receiving care in a federally qualified health center. Health Educ Res. 2019;34:310–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyz010.

Hernandez MY, Organista KC. Entertainment–Education? A Fotonovela? A new strategy to improve depression literacy and help-seeking behaviors in at-risk immigrant Latinas. Am J Community Psychol. 2013;52:224–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-013-9587-1.

Merchant RC, Clark MA, Santelices CA, Liu T, Cortés DE. Efficacy of an HIV/AIDS and HIV testing video for Spanish-speaking Latinos in healthcare and non-healthcare settings. AIDS Behav. 2015;19:523. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0889-6.

Molokwu JC, Shokar N, Dwivedi A. Impact of targeted education on colorectal cancer screening knowledge and psychosocial attitudes in a predominantly hispanic population. Fam Community Health. 2017;40:298–305. https://doi.org/10.1097/FCH.0000000000000165.

Pagán-Ortiz ME, Cortés DE. Feasibility of an online health intervention for Latinas with chronic pain. Rehabil Psychol. 2021;66:10–21. https://doi.org/10.1037/rep0000341.

Payán DD, Maggard-Gibbons M, Flórez KR, Mejía N, Hemmelgarn M, Kanouse D, et al. Taking care of yourself and your risk for breast cancer (CUIDARSE): a randomized controlled trial of a health communication intervention for Latinas. Health Educ Behav. 2020;47:569–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198120920529.

Phipps MG, Venkatesh KK, Ware C, Lightfoot M, Raker C, Rodriguez P. Project ESCUCHE: a Spanish-language radio-based intervention to increase science literacy. Rhode Island Med J. 2018:41–5.

Ramos IN, Ramos KS, Boerner A, He Q, Tavera-Garcia MA. Culturally-tailored education programs to address health literacy deficits and pervasive health disparities among hispanics in rural shelbyville. Kentucky J Community Med Health Educ. 2013;3:20475. https://doi.org/10.4172/2161-0711.1000250.

Reuland DS, Ko LK, Fernandez A, Braswell LC, Pignone M. Testing a Spanish-language colorectal cancer screening decision aid in Latinos with limited english proficiency: results from a pre-post trial and four month follow-up survey. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:53. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-12-53.

Lajonchere CM, Wheeler BY, Valente TW, Kreutzer C, Munson A, Narayanan S, et al. Strategies for disseminating information on biomedical research on autism to hispanic parents. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46:1038–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2649-5.

Riera A, Ocasio A, Tiyyagura G, Thomas A, Goncalves P, Krumeich L, et al. A web-based educational video to improve asthma knowledge for limited english proficiency Latino caregivers. J Asthma Off J Assoc Care Asthma. 2017;54:624. https://doi.org/10.1080/02770903.2016.1251597.

Robinson JK, Friedewald JJ, Desai A, Gordon EJ. Response across the health-literacy spectrum of kidney transplant recipients to a sun-protection education program delivered on tablet computers: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Cancer. 2015;1: e8. https://doi.org/10.2196/cancer.4787.

Sanchez K, Killian MO, Eghaneyan BH, Cabassa LJ, Trivedi MH. Culturally adapted depression education and engagement in treatment among Hispanics in primary care: outcomes from a pilot feasibility study. BMC Fam Pract. 2019;20:140. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-019-1031-7.

Valdez A, Napoles AM, Stewart S, Garza A. A randomized controlled trial of a cervical cancer education intervention for Latinas delivered through interactive, multimedia kiosks. J Cancer Educ Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ. 2018;33:222–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-016-1102-6.

Valenzuela-Araujo D, Godage SK, Quintanilla K, Dominguez Cortez J, Polk S, DeCamp LR. Leaving paper behind: improving healthcare navigation by Latino immigrant parents through video-based education. J Immigr Minor Health. 2021;23:329–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-020-00969-9.

West AM, Bittner EA, Ortiz VE. The effects of preoperative, video-assisted anesthesia education in Spanish on Spanish-speaking patients’ anxiety, knowledge, and satisfaction: a pilot study. J Clin Anesth. 2014;26:325–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinane.2013.12.008.

Calderon V, Cain R, Torres E, Lopez SR. Evaluating the message of an ongoing communication campaign to reduce the duration of untreated psychosis in a Latinx community in the United States. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2022;16:147–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.13140.

Chalela P, Muñoz E, Gallion KJ, Kaklamani V, Ramirez AG. Empowering Latina breast cancer patients to make informed decisions about clinical trials: a pilot study. Transl Behav Med. 2018;8:439–49. https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/ibx083.

Cullen SM, Osorio SN, Abramson EA, Kyvelos E. Improving caregiver understanding of liquid acetaminophen administration at primary care visits. Pediatrics. 2022;150: e2021054807. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2021-054807.

Dunlap JL, Jaramillo JD, Koppolu R, Wright R, Mendoza F, Bruzoni M. The effects of language concordant care on patient satisfaction and clinical understanding for Hispanic pediatric surgery patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50:1586–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.12.020.

Arun Mohan MD, M. Brian Riley MA, Brian Schmotzer MS, Dane R. Boyington P, Sunil Kripalani MD. Improving medication understanding among Latinos through illustrated medication lists. Am J Manag Care 2015;20.

Vadaparampil ST, Moreno Botero L, Fuzzell L, Garcia J, Jandorf L, Hurtado-de-Mendoza A, et al. Development and pilot testing of a training for bilingual community education professionals about hereditary breast and ovarian cancer among Latinas: ÁRBOLES Familiares. Transl Behav Med. 2022;12:ibab093. https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/ibab093.

Anderson PM, Krallman R, Montgomery D, Kline-Rogers E, Bumpus SM. The relationship between patient satisfaction with hospitalization and outcomes up to 6 months post-discharge in cardiac patients. J Patient Exp. 2020;7:1685–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/2374373520948389.

Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Viera A, Crotty K, et al. Health literacy interventions and outcomes: an updated systematic review. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US). 2011.

Diaz E, Ortiz-Barreda G, Ben-Shlomo Y, Holdsworth M, Salami B, Rammohan A, et al. Interventions to improve immigrant health. A scoping review. Eur J Public Health. 2017;27:433–9.

Walters R, Leslie SJ, Polson R, Cusack T, Gorely T. Establishing the efficacy of interventions to improve health literacy and health behaviours: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1040. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08991-0.

Funk C, Lopez MH. 2. Hispanic Americans’ experiences with health care. Pew Res Cent Sci Soc 2022. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2022/06/14/hispanic-americans-experiences-with-health-care/. Accessed 13 Oct 2022.

Ai AL, Noël LT, Appel HB, Huang B, Hefley WE. Overall Health and Health Care Utilization Among Latino American Men in the United States. Am J Mens Health. 2013;7:6–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988312452752.

Shafeek Amin N, Driver N. Health care utilization among Middle Eastern, Hispanic/Latino, and Asian immigrants in the United States: an application of Andersen’s behavioral model. Ethn Health. 2022;27:858–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2020.1830034.

Farmanova E, Bonneville L, Bouchard L. Organizational health literacy: review of theories, frameworks, guides, and implementation issues. Inq J Med Care Organ Provis Financ. 2018;55:0046958018757848. https://doi.org/10.1177/0046958018757848.

Moran MB, Murphy ST, Frank L, Baezconde-Garbanati L. The ability of narrative communication to address health-related social norms. Int Rev Soc Res. 2013;3:131–49. https://doi.org/10.1515/irsr-2013-0014.

Cupertino AP, Saint-Elin M, de los Rios JB, Engelman KK, Greiner KA, Ellerbeck EF, et al. Empowering promotores de salud as partners in cancer education and research in rural Southwest Kansas. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2015;42:15–22.

National academies of sciences, engineering, and medicine, health and medicine division, board on population health and public health practice, roundtable on health literacy. Community-based health literacy interventions: proceedings of a workshop. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2018.

Nutbeam D, McGill B, Premkumar P. Improving health literacy in community populations: a review of progress. Health Promot Int. 2018;33:901–11. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dax015.

Contributors

Not applicable.

Prior presentations

Primary Care Innovations Conference, University of Florida College of Medicine, June 10, 2022.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors meet the criteria for authorship in the following way: JH, LD, PP, LA, KZ, and AM were responsible for the study design, data analysis, and writing and review of the manuscript. RH, HN, and MH were responsible for the study design and writing and review of the manuscript. The authors have no acknowledgments.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hernandez, J., Demiranda, L., Perisetla, P. et al. A systematic review and narrative synthesis of health literacy interventions among Spanish speaking populations in the United States. BMC Public Health 24, 1713 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19166-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19166-6