Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic is affecting mental health and substance use (MHSU) issues worldwide. The purpose of this study was to characterize the literature on changes in cannabis use during the pandemic and the factors associated with such changes.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review by searching peer-reviewed databases and grey literature from January 2020 to May 2022 using the Arksey and O’Malley Framework. Two independent reviewers screened a total of 4235 documents. We extracted data from 129 documents onto a data extraction form and collated results using content analytical techniques.

Results

Nearly half (48%) of the studies reported an increase/initiation of cannabis use, while 36% studies reported no change, and 16% reported a decrease/cessation of cannabis use during the pandemic. Factors associated with increased cannabis use included socio-demographic factors (e.g., younger age), health related factors (e.g., increased symptom burden), MHSU factors (e.g., anxiety, depression), pandemic-specific reactions (e.g., stress, boredom, social isolation), cannabis-related factors (e.g., dependence), and policy-related factors (e.g., legalization of medical/recreational cannabis).

Conclusion

Public health emergencies like the COVID-19 pandemic have the potential to significantly impact cannabis use. The pandemic has placed urgency on improving coping mechanisms and supports that help populations adapt to major and sudden life changes. To better prepare health care systems for future pandemics, wide-reaching education on how pandemic-related change impacts cannabis use is needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is affecting the health of populations worldwide, including those living with mental health and substance use concerns [1,2,3]. Public health measures designed to protect public health by reducing person-to-person contact and virus transmission (e.g., physical distancing rules, closures of in-person offices, businesses, and educational institutions, and cancellation of public gatherings and events) are linked to increases in social isolation, worsening mental health symptoms, and drug-related harms [4,5,6].

Emerging evidence shows that the COVID-19 pandemic has influenced patterns of cannabis consumption; some studies have reported increases [7,8,9] or decreases in cannabis use [10, 11], while others have reported on the proportion of the population that increased, decreased, and did not change cannabis use during the pandemic [12,13,14,15,16]. Factors associated with changes in cannabis use during the pandemic include socio-demographic factors (e.g., age, sex, and gender), social isolation, boredom, depression, and anxiety about the pandemic [5, 6, 9, 17].

Chong et al. (2022) [18] conducted a scoping review of academic and grey literature on cannabis use from the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic to February 2021. In this review, the authors conducted a thematic analysis and identified themes related to cannabis use trends, context of use, modes of consumption, and factors contributing to and inhibiting use. This review showed that 33 out of the 76 documents examined change in cannabis use during the first year of the pandemic; of these, one-third reported increased cannabis use during the early phase of the pandemic. It also identified factors contributing to increased cannabis use, including boredom, anxiety, depression and accessibility to cannabis. In our scoping review, we explicitly focus on changes in cannabis use and expand the time frame to cover the first 2.5 years of the pandemic. We also report on a wider range of factors associated with such changes (e.g., socio-demographic, health-related, and policy-related factors). Our scoping review updates the literature and offers a new resource to those studying the effects of the pandemic on cannabis use and the factors that influence changes in patterns of use.

Our aim was to characterize the literature pertaining to changes in cannabis use during the COVD-19 pandemic. The objectives were to: (1) examine how the COVID-19 pandemic affected cannabis use among adults, and (2) to determine what factors were associated with changes in cannabis use during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

The methodology for this scoping review was based on established guidelines by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) [19], supplemented by Levac et al. (2010) [20]. We identified research questions aligned with the study objectives to guide the scoping review, identified relevant literature through academic and grey literature searches, selected studies based on pre-determined inclusion and exclusion criteria, conducted data extraction using a team based approach, and conducted a descriptive analysis to synthesize and report the data. We implemented a rigorous and standardized team-based review process that adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) reporting standards [21] (Supplementary Material 1). We did not provide a critical assessment of the quality of the evidence as this is an emerging area of research.

Step 1: identifying the research questions

We set out to answer the following two sets of questions: (1) How has the COVID-19 pandemic impacted cannabis use among adults? Has cannabis use increased, not changed, or decreased during the pandemic? In addition, have there been changes in types of cannabis consumption (e.g., recreational, medical) or modes of consumption (e.g., smoking, vaping)? (2) What factors were associated with changes in cannabis use during the COVID-19 pandemic? What are the socio-demographic factors, mental health factors, other substance use factors, pandemic related factors (e.g., COVID-19 related regulations, self-isolation), and other factors (e.g., accessibility, legalization) associated with changes in cannabis use during the pandemic?

Step 2: identifying relevant studies

We developed the search strategies in collaboration with a health science librarian (SB) to identify relevant published peer-reviewed literature and grey literature. For the peer-reviewed literature, we searched the bibliographic databases MEDLINE, Embase, PsycInfo, Scopus, Web of Science, LitCovid, and WHO COVID-19 using both subject headings (e.g., MeSH headings) and keywords to identify relevant research on cannabis and COVID-19. The search results were limited to studies published from January 1, 2020 to May 27, 2022, without any regional, gender or language restrictions. The reference lists of relevant studies were also checked to identify additional studies. The MEDLINE search strategy and a list of sites searched are available in Supplementary Material 2.

The grey literature search was international in scope and utilized a multipronged search approach to identify relevant research. The aims of the grey literature search were to locate information produced by either governmental agencies (e.g., Statistics Canada) or not-for-profit organizations (e.g., Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse), as well as unpublished research available from preprints. To identify relevant publications from governmental agencies and also non-governmental organizations, the search methods utilized grey literature search checklists [22, 23], a Google search using advanced search commands and a supplementary search in the WHO COVID-19 database. In addition, OSF preprints, medRxiv, and bioRxiv were searched for preprints. The grey literature search was also limited to records published since January 1, 2020.

We included both academic literature and grey literature articles published in 2020 or later that met the eligibility criteria for the scoping review. This included peer-reviewed articles utilizing diverse methodologies (e.g., surveys, interviews, randomized controlled trials) and documents/reports/publications from governments/health authorities and non-governmental organizations available online that reported changes in cannabis use during the COVID-19 pandemic among people aged 18 years or older. Eligibility criteria were developed based on team discussions. Publications and other sources were excluded if they: (1) did not include information about changes in cannabis use during the COVID-19 pandemic; (2) only included information about children/youth less than 18 years old; (3) had been published in a language other than English; (4) were duplicate documents; (5) were case reports, letters to the editor, commentaries, viewpoints, corrigendum, or conference abstracts/proceedings; (6) included cannabis use as a predictor but not the outcome of interest; (7) were about cannabis as a treatment option for COVID-19 infection; (8) describe cannabis use that was not self-reported (e.g., waste-water measurements, anonymous location data measurements, emergency department visits,); (9) were about the effects of cannabis on health issues during the pandemic (e.g., effect of cannabis use on COVID-19 infection, EVALI, or other health issues); and (10) were reviews or protocols for reviews.

Step 3: study selection

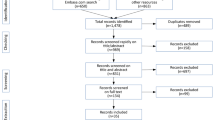

We used the Covidence online software program for systematic reviews [24] for the review process. A total of 4209 peer reviewed documents (MEDLINE n = 461, Embase n = 716, PsychInfo n = 104, Scopus n = 1108, Web of Science n = 576, LitCovid n = 280, WHO COVID database n = 766, medRxiv and bioRxiv n = 183, OSF preprints n = 15), 23 grey literature documents, and 3 additional references (i.e., two peer reviewed and one grey literature) were included for screening (Fig. 1). At title and abstract review stage, 2212 duplicate documents were removed. KM and JR independently screened 2023 titles and abstracts of the identified literature to determine eligibility based on established criteria. Conflicts were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (SR). Following the title and abstract review stage, 277 documents were identified as eligible for full text review. These full text documents were independently reviewed by two reviewers (JR and KM) and any conflicts were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (SR). A total of 129 documents (116 peer-reviewed articles, 13 grey literature documents) were included for data extraction.

Step 4: charting the data

To chart the data, the team developed, piloted and modified a tool detailing instructions and formatting guidelines for data extraction. KM and JR utilized this tool to independently extract information from approximately half the documents each using a Microsoft Excel [25] form and reviewed each other’s data extraction to ensure consistency. The following information was extracted: publication information (e.g., authors, publishing year), study location, legal status of cannabis where study was conducted, level of pandemic-related public health measures where study was conducted, study design, methodology, method, sample information and demographics, type of cannabis use (e.g., medical or recreational), modes of cannabis consumption (e.g., smoking, vaping, edibles), outcome measures, tool(s) used for measurement of change in cannabis use and associated factors, qualitative findings, and author’s main results and conclusion/interpretation for changes in cannabis use and/or associated factors.

Step 5: collating, summarizing and reporting the results

The information collected using the data extraction tool was quantitatively and descriptively summarized. In the Supplementary Material 3, Table A provides characteristics of the documents included in the review and Table B synthesizes results from our descriptive analysis of textual data. We met weekly to discuss progress, reporting, and interpretations. To effectively organize the data, the documents were broadly classified into population groups and then sub-grouped based on the change in cannabis use. For changes in cannabis use, studies were categorized as demonstrating increased use when reporting a statistically significant increase in use, a higher proportion of participants reporting increased use compared to no change or decreased use, or only reporting increased use; studies were categorized as no change when reporting no significant change in cannabis use, a higher proportion of participants reporting no change than increased or decreased use, or only reporting no change in cannabis use; and studies were categorized as decreased use when reporting significant decrease in cannabis use, a higher proportion of participants reporting decreased than no change or increased use, or only reporting decreased cannabis use during the pandemic. Qualitative data were similarly organized as increase, no change, or decrease, based on how many participants reported the direction of change in cannabis use. Among studies that reported diverse changes in prevalence, frequency, and/or quantity of cannabis use, the change in prevalence of cannabis use was prioritized over change in frequency, which was in turn prioritized over change in quantity of cannabis. Since there was high variability in the analysis conducted by the individual studies, with some adjusting for different sets of covariates and some not at all, we reported a general statistical change in cannabis use, i.e., increase, decrease, or no change, without specifying the covariates.

Only those factors that were associated with changes in cannabis use during the pandemic were included in this review. Factors associated with change in cannabis use from qualitative studies were extracted based on the participants’ descriptions (e.g., if participants mentioned that boredom during the pandemic increased their cannabis use). When factors were similar in nature, e.g., social isolation/loneliness/reduced social connection, they were organized into one category and then used to compare change in cannabis use. Additionally, there were mixed associations among factors associated with change in cannabis use across studies. For example, there were some instances where one study found a certain factor associated with increase in cannabis use and another study found the same factor associated with decrease in cannabis use (e.g., financial concerns associated with decrease in cannabis use in Salles et al. (2021) [10] and with increase in cannabis use in Imtiaz et al. (2021) [26]). All factors associated with cannabis use have been detailed by study in the Supplementary Material 3 (Table B), but for ease of interpretation only those factors that were consistently associated with either increase, decrease, or no change in cannabis use across studies were described in the results.

Results

Characteristics of the included studies

Table A in Supplementary Material 3 describes the characteristics of included studies. Out of the 129 documents included in this scoping review, studies were most commonly conducted in the USA (n = 50, 39%) or Canada (n = 28, 22%). Most of the included studies utilized cross-sectional (n = 82, 64%), longitudinal (n = 21, 16%), or repeated cross sectional (n = 14, 11%) study designs. Data collection was most commonly conducted through online surveys (n = 109, 85%), whereas a few studies collected data through in person/online/phone surveys (n = 10, 8%), in person/online/phone interviews (n = 8, 6%), or mixed surveys and interviews (n = 3, 2%). The sample sizes ranged from 16 to 227,258, ages ranged from a mean of 15.3 years to 58.1 years, proportion of females ranged from 9 to 88%, and proportion of Caucasian participants ranged from 11 to 92%.

The seven population groups included: (1) general adult population (n = 33, 26%); (2) young adults/students (n = 41, 32%); (3) people who use cannabis (n = 14, 11%); (4) people with health/mental health comorbidities (n = 10, 8%); (5) people who use substances (n = 17, 13%); (6) occupational groups (e.g., healthcare workers, veterans, athletes) (n = 7, 5%); and (7) sexual minority/2SLGBTQIA + groups (n = 7, 5%) (Table 1). Three articles had an overlap between two population groups (i.e., young adults/students as well as people who use cannabis, sexual minority/2SLGBTQIA + groups as well as people who use cannabis, and people with health/mental health comorbidities as well as people who use cannabis) [27,28,29], but since they all included information about people who use cannabis, these were included in that specific group.

Out of the 129 studies, only seven studies specifically examined change in type of cannabis use (i.e., medical or recreational cannabis use) [17, 29,30,31,32,33,34]. However, several studies assessed changes in specific modes of cannabis consumption [5, 8, 30, 32, 33, 35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45]. In addition, several studies described the level of public health measures during the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., stay-at-home orders, ban on gatherings, closure of non-essential businesses and schools) (Supplementary Material 3 - Table A). Of particular note, there were three studies that mentioned that cannabis dispensaries were deemed essential businesses and remained open during the pandemic [7, 30, 46]. Furthermore, three studies described different levels of public health measures at different stages of the pandemic and changes in cannabis use based on these measures [17, 47, 48]. Overall, several studies mentioned the legal status of cannabis in the area where the study was conducted: 16 studies (12%) mentioned legal/decriminalized status, 27 studies (21%) mentioned illegal status, and 86 studies (67%) were conducted in areas with both legal and illegal status (variable status) or did not specify the legal status of cannabis; however, only five studies statistically examined the changes in cannabis use during the pandemic based on the legal status of cannabis [4, 7, 30, 33, 49].

Change in cannabis use during the COVID-19 pandemic

Change in frequency or quantity of cannabis use

Table 1 and Table B in Supplementary Material 3 describes changes in cannabis use during the COVID-19 pandemic and the factors associated with those changes. Out of the 129 studies included in this scoping review, 63 (48%) reported increasing/initiating cannabis use, 46 (36%) reported no change, and 20 (16%) reported decreasing/cessation of cannabis use. Of particular note, 12 studies reported 0.3–17% of participants initiated cannabis use [8, 10, 11, 40, 43, 45, 50,51,52,53,54,55] and 14 studies found 0.7–65% of participants reported cessation of cannabis use during the COVID-19 pandemic [8, 10, 11, 16, 32, 39,40,41, 43, 45, 50, 53, 55, 56]. Table 1 specifies the change in cannabis use among different population categories, organized by increase/initiation, no change, or decrease/cessation in cannabis use within each of these populations.

Change in cannabis use among different population groups

The young adult/student population category contained the highest number of studies (n = 41), and a majority of studies reported an increase in cannabis use during the pandemic (n = 18, 44%), compared to no change (n = 14, 34%), or a decrease (n = 9, 22%) in cannabis use. Out of the 33 studies conducted among the general adult population, 15 (46%) reported an increase, 15 (46%) reported no change, and 3 (9%) reported a decrease in cannabis use. Among studies about people who use substances (n = 17), the majority found an increase in cannabis use during the pandemic (n = 10, 59%), whereas a few found a decrease (n = 5, 29%) or no change (n = 2, 12%) in cannabis use. Half the studies conducted among people who use cannabis (n = 7, 50%) found an increase in cannabis use, whereas 6 (43%) found no change and only one found a decrease (7%) in cannabis use. Half the studies conducted among people with health/mental health comorbidities (n = 5, 50%) found an increase in cannabis use and half (n = 5, 50%) found no change in cannabis use, with no study finding a decrease in cannabis use. Out of the seven studies conducted in occupational as well as sexual/gender minority groups, four (57%) found an increase, two (29%) found no change and one (14%) found a decrease in cannabis use (Table 1; Fig. 2).

Thus, a majority of studies in most of the studied populations reported an increase in cannabis use as compared to decrease or no change during the COVID-19 pandemic. These findings may differ based on how cannabis use was measured in each of these studies and which measurement was prioritized during our categorization of data. In addition, very few studies included representative population data or utilized similar methodologies or time frames for data collection.

Change in type of cannabis use and modes of administration

Studies measuring change in the type of cannabis use reported mixed results, that is, two studies found an increase in recreational cannabis use [17, 31] and one found a decrease [34]; two studies found no change in medical cannabis use [29, 30] and two found an increase in use [32, 33]. Similarly, studies measuring change in smoking as a mode of cannabis consumption reported variable results, for example, three studies found an increase in smoking [5, 32, 41], two found a decrease [8, 43], and three found no change [40, 42, 45]. However, more studies found an increase in other modes of consumption rather than no change or decrease. For example, five studies found an increase in vaping [5, 36, 37, 43, 44], and three found no change [39, 42, 45], whereas four studies found an increase in the use of edibles [5, 30, 35, 43], one found no change [45] and one found a decrease [38]. Thus, data about the change in types and modes of cannabis consumption revealed variable findings. However, there was a lack of standardized measurements while studying such changes, for example, the most common method of data collection was a survey question about change in cannabis use with the options of increase, no change, or decrease, and it was only used among 28 (22%) of documents (Appendix C).

Factors associated with change in cannabis use

Socio-demographic factors

Among the studies conducted with the general adult population (age range 15 to 75 + years), younger people were found to increase their cannabis use [12, 14, 16, 26, 57,58,59,60,61]. However, among studies conducted with young adults/students (age range 15 to 29 years), older members of these younger groups were found to increase cannabis use [62, 63]. In general, more studies reported increased cannabis use among females [7, 12, 30, 32, 33, 39, 41] than males [46, 59, 64]. Those who identified as a sexual/gender minority [28, 65, 66], had lower income [7, 59], lower educational levels [16, 26, 53, 60], or were unemployed or lost employment [27, 32, 67, 68], were found to be more likely to increase/initiate cannabis use during the pandemic. Two studies found increased cannabis use among non-Caucasians [27, 63] whereas one study found increased use among Caucasians [7]. In addition, those living alone [53, 69], or not living with parents [64, 68, 70] were found to increase cannabis use and those living with children [53] or with parents [38, 70] were found to decrease cannabis use.

Health-related factors

A few studies examined the impact of the pandemic on cannabis use in relation to concerns about general health, or physical health disorders such as endometriosis or obesity. For example, those who were focused on their health during the pandemic were found to decrease their cannabis use [71, 72], whereas those who experienced health issues (e.g., obesity) [16, 73], increased symptom burden [4, 35], or reduced access to healthcare [35] were found to increase/initiate cannabis use during the pandemic.

Mental health or other substance use factors

Those who experienced anxiety [5, 6, 12, 13, 29, 35, 42, 43, 45, 57, 74,75,76,77], depression [5, 6, 12, 13, 29, 43, 45, 57, 62, 70, 71, 74, 75], PTSD [55, 65], suicidal ideation [78], impulsivity [65], and lower dispositional resilience [68] were found to increase cannabis use. People who experienced polysubstance/use of substances other than cannabis [4, 47, 58] or substance use concerns [79] were found to increase cannabis use during the pandemic.

Pandemic specific reactions

Those who experienced stress [5, 8, 12, 35, 42, 58, 61, 72, 75, 80, 81], boredom [4, 10, 36, 38, 41, 43, 45, 54, 61, 71, 77, 80, 81], more free time [33, 38, 42, 43, 45, 71], disrupted daily routine [42, 80, 81], work from home [32, 72], or social isolation/reduced social support [5, 8, 12, 17, 47, 54, 61, 74, 80, 82] due to the pandemic were found to increase/initiate cannabis use. Those who perceived that cannabis use would not increase their risk of COVID-19 [55] or those who experienced COVID-19 symptoms [32] increased cannabis use, whereas those who were at risk of COVID-19 [33] or perceived more harm due to COVID-19 [42] decreased their cannabis use. Changes in cannabis use based on the level of public health measures revealed mixed results, with one study reporting decreased cannabis use with easing of lockdown measures [17] and two reporting increased cannabis use with easing of/lesser lockdown measures [47, 48].

Cannabis-related factors

Those who experienced cannabis craving/dependence [8, 39, 83], had easier access to cannabis [8, 61, 81], or had higher stockpile of cannabis [80] were found to increase/initiate cannabis use whereas decrease/cessation of cannabis use was reported among those who had reduced opportunities to consume cannabis [38, 41, 42, 61, 71, 77, 80, 84], reduced access to cannabis [4, 35, 36, 77, 84], or lower stockpile of cannabis [72, 80].

Policy-related factors

Among studies conducted with the general adult population/people who use cannabis, people who lived in areas where medical and recreational cannabis use was legal [30, 33, 81], or only medical cannabis use was legal [7], were found to increase/initiate cannabis use, whereas those who lived in areas where cannabis was prohibited/illegal were found to decrease cannabis use [4, 7] during the pandemic. One study conducted by Graupensperger et al. (2021) [49] among young adults found no change in cannabis use among participants who lived in Washington, where cannabis was legal, compared to those who lived outside Washington.

Regardless of whether studies assessed change in cannabis use based on cannabis legal status, out of the studies that were conducted in legal/decriminalized jurisdictions, 7 (44%) reported increase, 8 (50%) reported no change, and 1 (6%) reported decrease in cannabis use; among studies conducted in jurisdictions were cannabis was illegal, 13 (48%) reported increase, 6 (22%) reported no change, and 8 (30%) reported decrease in cannabis use; and studies that did not specify legal status or had variable legal status (conducted in area with both legal or illegal status), 43 (50%) reported increase, 32 (37%) reported no change, and 11 (13%) reported decrease in cannabis use. Figure 3 shows a step-wise increase in the proportion of studies that document decreases or cessation of cannabis use going from legal to illegal jurisdictions.

Discussion

Our scoping review examined how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted cannabis use and reported on factors associated with these changes. More studies were found to report increased cannabis use during the pandemic among youth/students, people who use cannabis, people who use other substances, occupational groups, and sexual/gender minority groups than no change or decrease in cannabis use during the pandemic. These patterns seem to be consistent with existing evidence indicating that greater cannabis use is more prevalent among specific populations (e.g., youth, people who use substances, and sexual minorities) compared to the general population [85,86,87]. An equal number of studies reported no change or increased cannabis use among the general population and people with health/mental health comorbidities, and among studies reporting decreases in cannabis use, a majority of studies belonged to the young adult/student group. The finding about initiation and cessation of cannabis use suggests that the pandemic may have acted as a trigger for starting as well as stopping cannabis use. Our scoping review shows a higher proportion of studies reporting an increase/initiation in cannabis use (48%) compared to a recent review conducted by Chong et al. (2022) [18] in which 11 out of 33 studies (33.3%) found more users reporting increased cannabis use than decreased, and 27% of studies reporting stable use. In addition, the review by Chong et al. (2022) [18] did not include studies examining initiating cannabis use during the COVID-19 pandemic whereas this scoping review identified several studies reporting on initiation and cessation of cannabis use during the pandemic. The divergent findings between the two scoping reviews could be due to a number of factors including the longer observation period in this scoping review (2.5 years vs. 1 year), narrower inclusion criteria focusing on changes in cannabis use, and more specific criteria for the categorization of change in cannabis use utilized in this scoping review.

Several socio-demographic factors were studied in relation to changes in cannabis use. Some studies found younger age to be associated with increases in cannabis use during the pandemic. Data about the factors associated with increases in cannabis use among young adults/students revealed factors similar to the adult population, such as experiencing mental health concerns, boredom, social isolation, and stress during the pandemic. However, the review found mixed reports about changes in cannabis use with respect to gender and ethnicity. Some findings in this review such as increased cannabis use among lower income and lower education groups may illustrate the need for healthcare decision makers to develop strategies that focus on the healthcare needs of specific population groups [12, 27].

Two studies reported that cannabis inhalation reduced during the COVID-19 pandemic due to concerns related to respiratory health [30, 35], however, other studies examining changes in smoking or vaping found variable results [5, 36, 37]. Similarly, studies examining changes in recreational or medical cannabis use due to the COVID-19 pandemic reported variable results [17, 29,30,31,32,33,34]. The diverse population groups and methodologies utilized to assess change in modes and types of cannabis use could potentially contribute to inconsistent findings. There is a need to standardize the measurement of types of cannabis consumption and modes of consumption (i.e., examining changes in smoking, vaping, edibles), as the lack of consensus on how cannabis should be measured limits the ability to accurately assess cannabis use and generalize its effects [88]. Further research is needed to understand the impact that health emergencies such as pandemics may have on consumption of different modes or types of cannabis use, including changes in frequency of use and the quantity consumed.

The specific pandemic related factors found to be related to increases in cannabis use (e.g., social isolation and disrupted daily routine) as well as mental health factors (e.g., anxiety and depression) point to a need for additional public health supports and strategies for managing the stressors and mental health impacts associated with the pandemic [4, 5, 34, 62, 81]. In addition, factors specifically associated with initiating cannabis use during the pandemic included amplification of health issues, reduced access to health care, and mental health impacts of the pandemic. Findings suggest a need to maintain access to health care and other supports during pandemics. Strategies to improve access to an already overburdened healthcare system include utilizing digital health applications such as telehealth approaches, modifying treatment plans to include newer technological approaches, and providing options for in-person versus remote care [89, 90].

The mixed findings about changes in cannabis use associated with public health measures (e.g., lockdowns) could be attributed to other associated factors. For example, increased stress due to stricter lockdowns could be related to increased cannabis use, and increased access and increased social opportunities to consume cannabis during easing of lockdown measures could be related to increased cannabis use. Three studies mentioned cannabis dispensaries were deemed essential and found increased cannabis use, however, this public health measure was not studied as a factor associated with change in cannabis use in these studies. In addition, the studies that assessed changes in cannabis use in the general population associated with legalization found increased cannabis use in jurisdictions where recreational and/or medical cannabis was legal. Similarly, most studies that were conducted in legal/decriminalized jurisdictions found either no change or increased cannabis use whereas a higher proportion of those studies conducted in illegal jurisdictions found decreased cannabis use during the pandemic. This finding may be explained by the pandemic creating a greater disruption in illegal markets during the pandemic (e.g., due to stay-at-home orders) [32, 91,92,93,94] relative to legal markets, particularly in jurisdictions where cannabis stores were deemed essential services (e.g., in Canada, [46, 95]). However, there is an urgent need for more research focusing on the impact of public health measures as well as legalization policies on cannabis use.

Overall, the findings from this study can be used by health care and policy decision makers to understand the impact of the pandemic on cannabis use and the factors associated with change in use. Findings may aid policy makers in developing strategies to inform the general population about risks of cannabis related harms, to address and ultimately prevent the consequences of increased cannabis consumption, and reduce the burden on the healthcare systems during pandemics. A few strategies for public policy decision makers include continued monitoring of cannabis use during and post pandemic, public guidance about prevention or moderation of cannabis use and implementation of measures to address the impacts of increased cannabis use [96].

This scoping review has several limitations. Only studies in English that included participants 18 years or older were included in this review which limits the generalizability of findings. The lack of representativeness of the data in the studies also limits its generalizability. There were several important topics that were excluded from this scoping review including examinations of cannabis use as a predictor [97,98,99], a treatment option for COVID-19 [100,101,102], and proxy measures of cannabis use (e.g., waste water measurements, emergency department visits) [103,104,105]). These topics were outside the scope of this review, but would be valuable as separate reviews in their own right. The studies that were included in this review were based on self-reported cannabis use data which can be influenced by recall and social desirability biases. It is possible that some studies were missed or that some studies that were identified may not be publicly available. To reduce the number of studies excluded, we implemented a standardized process to reach authors to request articles. Additionally, the criteria used to categorize change in cannabis use could potentially impact the findings of this review. Although we categorized changes in cannabis use as increased, no change, or decreased, the same study may have reported all three changes and thus could be interpreted in different ways; however, utilizing an organized approach helped synthesize and report the findings. Since the established scoping review methodology by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) [19] was use in this study, we did not conduct a quality assessment of included studies. Stakeholder consultations were not conducted for this scoping review since the focus was on self-reported change in cannabis use during the pandemic.

Conclusion

Cannabis use has been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic due to several associated factors. The information from this review sheds light on potentially concerning patterns of cannabis use following global health emergencies and can be utilized by healthcare workers and decision makers to support people who use cannabis and to prevent cannabis related harms during future pandemics. Further research is needed to understand the change in specific types and modes of cannabis use, as well as the impact of public health policies on cannabis use.

Data availability

The dataset created and used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Avena NM, Simkus J, Lewandowski A, Gold MS, Potenza MN. Substance use disorders and behavioral addictions during the COVID-19 pandemic and COVID-19-related restrictions. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:653674.

Czeisler MÉ, Wiley JF, Facer-Childs ER, Robbins R, Weaver MD, Barger LK, et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during a prolonged COVID-19-related lockdown in a region with low SARS-CoV-2 prevalence. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;140:533–44.

Chiappini S, Guirguis A, John A, Corkery JM, Schifano F. COVID-19: the hidden impact on mental health and drug addiction. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:767.

Boehnke KF, McAfee J, Ackerman JM, Kruger DJ. Medication and substance use increases among people using cannabis medically during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Drug Policy. 2021;92:103053.

Bonar EE, Chapman L, McAfee J, Goldstick JE, Bauermeister JA, Carter PM, et al. Perceived impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on cannabis-using emerging adults. Translational Behav Med. 2021;11(7):1299–309.

Dyar C, Morgan E, Kaysen D, Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Risk factors for elevations in substance use and consequences during the COVID-19 pandemic among sexual and gender minorities assigned female at birth. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;227:109015.

Brenneke SG, Nordeck CD, Riehm KE, Schmid I, Tormohlen KN, Smail EJ, et al. Trends in cannabis use among US adults amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Drug Policy. 2022;100:103517.

Benschop A, Van Bakkum F, Noijen J. Changing patterns of substance use during the coronavirus pandemic: self-reported use of Tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, and other Drugs. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12.

Bonny-Noach H, Cohen-Louck K, Levy I. Substances use between early and later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in Israel. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2021;10(1):1–7.

Salles J, Yrondi A, Marhar F, Andant N, Dorlhiac RA, Quach B et al. Changes in cannabis consumption during the global covid-19 lockdown: the international COVISTRESS study. Front Psychiatry. 2021:1985.

Weber CAT, Monteiro IT, Gehrke JM, de Souza WS. The Use of Psychoactive Substances in the Context of the Covid-19 Pandemic in Brazil. medRxiv. 2020.

Brotto LA, Chankasingh K, Baaske A, Albert A, Booth A, Kaida A, et al. The influence of sex, gender, age, and ethnicity on psychosocial factors and substance use throughout phases of the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(11):e0259676.

Dozois DJ. Anxiety and depression in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national survey. Can Psychol. 2021;62(1):136.

El-Gabalawy R, Sommer JL. We are at risk too: the Disparate Mental Health impacts of the pandemic on younger generations: Nous Sommes Aussi à Risque: Les Effets Disparates De La Pandémie Sur La Santé Mentale Des Générations Plus Jeunes. Can J Psychiatry. 2021;66(7):634–44.

Robillard R, Daros AR, Phillips JL, Porteous M, Saad M, Pennestri M-H, et al. Emerging New Psychiatric symptoms and the worsening of pre-existing Mental disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic: a Canadian Multisite Study: Nouveaux symptômes psychiatriques émergents et détérioration des troubles mentaux préexistants durant la pandémie de la COVID-19: une étude canadienne multisite. Can J Psychiatry. 2021;66(9):815–26.

Rolland B, Haesebaert F, Zante E, Benyamina A, Haesebaert J, Franck N. Global changes and factors of increase in caloric/salty food intake, screen use, and substance use during the early COVID-19 containment phase in the general population in France: survey study. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance. 2020;6(3):e19630.

Sznitman S, Rosenberg D, Lewis N. Are COVID-19 health-related and socioeconomic stressors associated with increases in cannabis use in individuals who use cannabis for recreational purposes? Substance Abuse. 2022;43(1):301–8.

Chong WW-Y, Acar ZI, West ML, Wong F. A scoping review on the Medical and recreational use of Cannabis during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cannabis and cannabinoid research; 2022.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):1–9.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Ali H, Calabria B, Phillips B, Singleton J, Sigmundsdottir L, Congreve E, et al. Searching the grey literature to access information on Drugs, alcohol and HIV/AIDS research: an update. Sydney: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre; 2010.

Drugs, CAf. Health Ti. Grey matters: a practical tool for searching health-related grey literature. Ottawa, ON. 2015.

Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence systematic review software. Australia: Melbourne; 2017.

Microsoft Corporation. Microsoft Excel. 2018.

Imtiaz S, Wells S, Rehm J, Hamilton HA, Nigatu YT, Wickens CM, et al. Cannabis use during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada: a repeated cross-sectional study. J Addict Med. 2021;15(6):484.

Fedorova EV, Wong CF, Conn BM, Ataiants J, Iverson E, Lankenau SE. COVID-19’s impact on Substance Use and well-being of younger adult Cannabis users in California: a mixed methods Inquiry. J Drug Issues. 2021:00220426211052673.

Gattamorta KA, Salerno JP, Islam JY, Vidot DC. Mental health among LGBTQ cannabis users during the COVID-19 pandemic: analysis of the COVID-19 cannabis health study. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2021;8(2):172.

Rodriguez DL, Vidot DC, Camacho-Rivera M, Islam JY. Mental health symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic among cancer survivors who endorse cannabis: results from the COVID-19 cannabis health study. Curr Oncol. 2022;29(3):2106–18.

Assaf RD, Gorbach PM, Cooper ZD. Changes in medical and non-medical cannabis use among United States adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Drug Alcohol Abus. 2022:1–7.

Lewis N, Sznitman SR. Too much information? Excessive media Use, Maladaptive Coping, and increases in problematic Cannabis Use during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2022:1–10.

Mezaache S, Donadille C, Martin V, Le Brun Gadelius M, Appel L, Spire B, et al. Changes in cannabis use and associated correlates during France’s first COVID-19 lockdown in daily cannabis users: results from a large community-based online survey. Harm Reduct J. 2022;19(1):1–10.

Lake S, Assaf RD, Gorbach PM, Cooper ZD. Selective changes in Medical Cannabis Use early in the COVID-19 pandemic: findings from a web-based sample of adults in the United States. Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research; 2022.

Bartel S, Sherry S, Stewart S. Self-isolation: a significant contributor to cannabis use during the COVID-19 pandemic. Substance Abuse. 2020;41(4):409–12.

Armour M, Sinclair J, Cheng J, Davis P, Hameed A, Meegahapola H et al. Endometriosis and cannabis consumption during the covid-19 pandemic: an international cross-sectional survey. Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research. 2022.

Case KR, Clendennen SL, Shah J, Tsevat J, Harrell MB. Changes in marijuana and nicotine vaping perceptions and use behaviors among young adults since the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. Addict Behav Rep. 2022;15:100408.

Gaiha SM, Lempert LK, Halpern-Felsher B. Underage youth and young adult e-cigarette use and access before and during the coronavirus Disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Netw open. 2020;3(12):e2027572–e.

Merrill JE, Stevens AK, Jackson KM, White HR. Changes in cannabis consumption among college students during CoViD-19. J Stud Alcohol Drug. 2022;83(1):55–63.

Nguyen N, Gaiha SM, Halpern-Felsher B. Self-reported changes in cannabis vaping among US adolescents and young adults early in the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev Med Rep. 2021;24:101654.

Shapiro O, Gannot RN, Green G, Zigdon A, Zwilling M, Giladi A, et al. Risk behaviors, Family Support, and Emotional Health among adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic in Israel. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(7):3850.

Van Laar MW, Oomen PE, Van Miltenburg CJ, Vercoulen E, Freeman TP, Hall WD. Cannabis and COVID-19: reasons for concern. Front Psychiatry. 2020:1419.

Yousufzai SJ, Cole AG, Nonoyama M, Barakat C. Changes in cannabis consumption among emerging adults in relation to policy and public health developments. Subst Use Misuse. 2022;57(5):730–41.

Peacock A, Karlsson A, Uporova J, Price O, Chan R, Swanton R et al. Australian Drug Trends 2020: Key Findings from the National Ecstasy and Related Drugs Reporting System (EDRS) Interviews. 2020.

Johnston LD, Miech RA, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2021: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. 2022.

Peacock A, Uporova J, Karlsson A, Price O, Gibbs D, Swanton R et al. Australian drug trends 2020: key findings from the National Illicit Drug Reporting System (IDRS) interviews. 2021.

Currie CL. Adult PTSD symptoms and substance use during Wave 1 of the COVID-19 pandemic. Addict Behav Rep. 2021;13:100341.

Gaume J, Schmutz E, Daeppen J-B, Zobel F. Evolution of the illegal substances market and substance users’ Social Situation and Health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(9):4960.

Slemon A, Richardson C, Goodyear T, Salway T, Gadermann A, Oliffe JL, et al. Widening mental health and substance use inequities among sexual and gender minority populations: findings from a repeated cross-sectional monitoring survey during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada. Psychiatry Res. 2022;307:114327.

Graupensperger S, Fleming CB, Jaffe AE, Rhew IC, Patrick ME, Lee CM. Changes in young adults’ alcohol and marijuana use, norms, and motives from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Adolesc Health. 2021;68(4):658–65.

Bruton L, Featherstone T, Gibney S. Impact of COVID-19 on Drug and Alcohol Services and People who use Drugs in Ireland: A report of survey findings.; 2021.

Pedersen ER, Davis JP, Fitzke RE, Lee DS, Saba S. American veterans in the era of COVID-19: reactions to the pandemic, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, and Substance Use behaviors. Int J Mental Health Addict. 2021:1–16.

Rogers AH, Shepherd JM, Garey L, Zvolensky MJ. Psychological factors associated with substance use initiation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293:113407.

Sylvestre M-P, Dinkou GDT, Naja M, Riglea T, Pelekanakis A, Bélanger M, et al. A longitudinal study of change in substance use from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic in young adults. Lancet Reg Health-Americas. 2022;8:100168.

Vanderbruggen N, Matthys F, Van Laere S, Zeeuws D, Santermans L, Van den Ameele S, et al. Self-reported alcohol, Tobacco, and cannabis use during COVID-19 lockdown measures: results from a web-based survey. Eur Addict Res. 2020;26(6):309–15.

Wang Y, Ibañez GE, Vaddiparti K, Stetten NE, Sajdeya R, Porges EC, et al. Change in marijuana use and its associated factors among persons living with HIV (PLWH) during the COVID-19 pandemic: findings from a prospective cohort. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;225:108770.

Rantis K, Panagiotidis P, Parlapani E, Holeva V, Tsapakis E, Diakogiannis I. Substance use during the COVID-19 pandemic in Greece. J Subst Use. 2021:1–8.

MacEachern KH, Venugopal J, Varin M, Weeks M, Hussain N, Baker MM. Applying a gendered lens to understanding self-reported changes in alcohol and cannabis consumption during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada, September to December 2020. Volume 41. Health Promotion & Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada: Research, Policy & Practice.; 2021. 11.

Ben Salah A, DeAngelis BN, Morales D, Bongard S, Leufen L, Johnson R, et al. A multinational study of psychosocial stressors and symptoms associated with increased substance use during the early wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of polysubstance use. Cogent Psychol. 2022;9(1):2054162.

Varin M, MacEachern KH, Hussain N, Baker MM. At-a-glance-Measuring self-reported change in alcohol and cannabis consumption during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada: Research Policy and Practice. 2021;41(11):325.

Zajacova A, Jehn A, Stackhouse M, Denice P, Ramos H. Changes in health behaviours during early COVID-19 and socio-demographic disparities: a cross-sectional analysis. Can J Public Health. 2020;111(6):953–62.

Statistics Canada. Alcohol and cannabis use during the pandemic: Canadian Perspectives Survey Series 6.; 2021.

Busse H, Buck C, Stock C, Zeeb H, Pischke CR, Fialho PMM, et al. Engagement in health risk behaviours before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in German university students: results of a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4):1410.

Clendennen SL, Case KR, Sumbe A, Mantey DS, Mason EJ, Harrell MB. Stress, dependence, and COVID-19–related changes in past 30-day Marijuana, electronic cigarette, and cigarette use among youth and young adults. Tob Use Insights. 2021;14:1179173X211067439.

van Hooijdonk KJ, Rubio M, Simons SS, van Noorden TH, Luijten M, Geurts SA, et al. Student-, study-and COVID-19-Related predictors of students’ Smoking, binge drinking and Cannabis Use before and during the initial COVID-19 lockdown in the Netherlands. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(2):812.

Hicks TA, Chartier KG, Buckley TD, Reese D, Working Group TSfS, Vassileva J, et al. Divergent changes: abstinence and higher-frequency substance use increase among racial/ethnic minority young adults during the COVID-19 global pandemic. Am J Drug Alcohol Abus. 2022;48(1):88–99.

Somé NH, Shokoohi M, Shield KD, Wells S, Hamilton HA, Elton-Marshall T, et al. Alcohol and cannabis use during the COVID-19 pandemic among transgender, gender-diverse, and cisgender adults in Canada. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1–9.

Howard K, Grigsby TJ, Haskard-Zolnierek KB, Deason RG, Howard JT. Pandemic-related work status is associated with self-reported increases in substance use. J Workplace Behav Health. 2021;36(3):250–7.

Romm KF, Patterson B, Crawford ND, Posner H, West CD, Wedding D, et al. Changes in young adult substance use during COVID-19 as a function of ACEs, depression, prior substance use and resilience. Substance Abuse. 2022;43(1):212–21.

Tavolacci MP, Wouters E, Van de Velde S, Buffel V, Déchelotte P, Van Hal G, et al. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on health behaviors among students of a French university. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(8):4346.

Tholen R, Ponnet K, Van Hal G, De Bruyn S, Buffel V, Van de Velde S, et al. Substance use among Belgian higher education students before and during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(7):4348.

Knell G, Robertson MC, Dooley EE, Burford K, Mendez KS. Health behavior changes during COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent stay-at-home orders. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(17):6268.

Miller K, Laha-Walsh K, Albright DL, McDaniel J. Cannabis use during the COVID-19 pandemic: results from a longitudinal study of Cannabis users. J Subst Use. 2022;27(1):38–42.

Glazer SA, Vallis M. Weight gain, weight management and medical care for individuals living with overweight and obesity during the COVID-19 pandemic (EPOCH study). Obesity Science & Practice; 2022.

Somé NH, Wells S, Felsky D, Hamilton HA, Ali S, Elton-Marshall T, et al. Self-reported mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic and its association with alcohol and cannabis use: a latent class analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22(1):1–13.

de Quervain D, Aerni A, Amini E, Bentz D, Coynel D, Gerhards C et al. The Swiss corona stress study. 2020.

Lin SL. Generalized anxiety disorder during COVID-19 in Canada: gender-specific association of COVID-19 misinformation exposure, precarious employment, and health behavior change. J Affect Disord. 2022;302:280–92.

New Zealand Drug Foundation. Pulse survey during Alert Level Four of addiction services and people who use drugs in New Zealand.; 2020.

Goodyear T, Slemon A, Richardson C, Gadermann A, Salway T, Dhari S, et al. Increases in Alcohol and Cannabis Use Associated with deteriorating Mental Health among LGBTQ2 + adults in the Context of COVID-19: a repeated cross-sectional study in Canada, 2020–2021. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(22):12155.

Mental Health Commission of Canada. Mental Health and Substance Use During COVID-19: Summary Report. 2021.

NANOS Research. COVID-19 and increased alcohol consumption: NANOS poll summary report. Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction Ottawa ON, Canada; 2020.

Bochicchio LA, Drabble LA, Riggle ED, Munroe C, Wootton AR, Hughes TL. Understanding alcohol and marijuana use among sexual minority women during the COVID-19 pandemic: a descriptive phenomenological study. J Homosex. 2021;68(4):631–46.

Cousijn J, Kuhns L, Larsen H, Kroon E. For better or for worse? A pre–post exploration of the impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on cannabis users. Addiction. 2021;116(8):2104–15.

Papp LM, Kouros CD. Effect of COVID-19 disruptions on young adults’ affect and substance use in daily life. Psychol Addict Behav. 2021.

Otiashvili D, Mgebrishvili T, Beselia A, Vardanashvili I, Dumchev K, Kiriazova T, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on illicit drug supply, drug-related behaviour of people who use Drugs and provision of drug related services in Georgia: results of a mixed methods prospective cohort study. Harm Reduct J. 2022;19(1):1–15.

Hango DW, LaRochelle-Côté S. Association between the frequency of cannabis use and selected social indicators. Statistics Canada = Statistique Canada; 2018.

Sussman S, Sinclair DL. Substance and behavioral addictions, and their consequences among vulnerable populations. MDPI; 2022. p. 6163.

Jeffers AM, Glantz S, Byers A, Keyhani S. Sociodemographic characteristics associated with and prevalence and frequency of cannabis use among adults in the US. JAMA Netw open. 2021;4(11):e2136571–e.

Freeman TP, Lorenzetti V. Standard THC units’: a proposal to standardize dose across all cannabis products and methods of administration. Addiction. 2020;115(7):1207–16.

Blithikioti C, Nuño L, Paniello B, Gual A, Miquel L. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on individuals under treatment for substance use disorders: risk factors for adverse mental health outcomes. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;139:47–53.

Kopelovich SL, Monroe-DeVita M, Buck BE, Brenner C, Moser L, Jarskog LF, et al. Community mental health care delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic: practical strategies for improving care for people with serious mental Illness. Commun Ment Health J. 2021;57(3):405–15.

Fernández-Artamendi S, Ruiz MJ, López-Núñez C. Analyzing the behavior of Cannabis users during the COVID-19 confinement in Spain. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(21):11324.

Imboden C, Claussen MC, Iff S, Quednow BB, Seifritz E, Spörri J et al. COVID-19 lockdown 2020 changed patterns of Alcohol and Cannabis Use in Swiss Elite athletes and bodybuilders: results from an online survey. Front Sports Act Living. 2021;3.

Jodczyk AM, Kasiak PS, Adamczyk N, Gębarowska J, Sikora Z, Gruba G, et al. PaLS study: Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Usage among Polish University students in the context of stress caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(3):1261.

Lintzeris N, Deacon RM, Hayes V, Cowan T, Mills L, Parvaresh L et al. Opioid agonist treatment and patient outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic in south east Sydney, Australia. Drug and alcohol review. 2021.

Pocuca N, London-Nadeau K, Geoffroy M-C, Chadi N, Séguin JR, Parent S et al. Changes in emerging adults’ alcohol and cannabis use from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from a prospective birth cohort. Psychol Addict Behav. 2022.

Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Half of cannabis users increased consumption during first wave of COVID-19. 2021 [Available from: https://www.camh.ca/en/camh-news-and-stories/half-cannabis-users-increased-consumption-1st-wave-covid-19.

Wang QQ, Kaelber DC, Xu R, Volkow ND. COVID-19 risk and outcomes in patients with substance use disorders: analyses from electronic health records in the United States. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26(1):30–9.

Tandan N, Regmi MR, Maini R, Ibrahim AM, Koester C, Garcia OEL et al. Age Matters: COVID-19 Prevalence in a Vaping Adolescent Population–An Observational Study. medRxiv. 2020.

Rosoff DB, Yoo J, Lohoff FW. A genetically-informed study disentangling the relationships between tobacco smoking, cannabis use, alcohol consumption, substance use disorders and respiratory infections, including COVID-19. medRxiv. 2021.

Nguyen LC, Yang D, Nicolaescu V, Best TJ, Ohtsuki T, Chen S-N et al. Cannabidiol inhibits SARS-CoV-2 replication and promotes the host innate immune response. bioRxiv. 2021.

Mahmud MS, Hossain MS, Ahmed AF, Islam MZ, Sarker ME, Islam MR. Antimicrobial and antiviral (SARS-CoV-2) potential of cannabinoids and Cannabis sativa: a comprehensive review. Molecules. 2021;26(23):7216.

Sarkar I, Sen G, Bhattacharya M, Bhattacharyya S, Sen A. In silico inquest reveals the efficacy of Cannabis in the treatment of post-covid-19 related neurodegeneration. J Biomol Struct Dynamics. 2021:1–10.

Capuzzi E, Di Brita C, Caldiroli A, Colmegna F, Nava R, Buoli M, et al. Psychiatric emergency care during Coronavirus 2019 (COVID 19) pandemic lockdown: results from a Department of Mental Health and Addiction of northern Italy. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293:113463.

Ashby NJ. Anonymized location data reveals trends in legal Cannabis use in communities with increased mental health risks at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. J Addict Dis. 2021;39(4):436–40.

Arillotta D, Guirguis A, Corkery JM, Scherbaum N, Schifano F. COVID-19 pandemic impact on Substance Misuse: a social media listening, mixed method analysis. Brain Sci. 2021;11(7):907.

Aldridge J, Garius L, Spicer J, Harris M, Moore K, Eastwood N. Drugs in the time of COVID: the UK drug market response to lockdown restrictions. 2021.

Das A, Singh P, Bruckner TA. State lockdown policies, mental health symptoms, and using substances. Addict Behav. 2022;124:107084.

Statistics Canada. Tables 13-10-0383-01 Prevalence of cannabis use in the past three months, self-reported. 2020.

Turna J, Patterson B, Goldman Bergmann C, Lamberti N, Rahat M, Dwyer H et al. Mental health during the first wave of COVID-19 in Canada, the USA, Brazil and Italy. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2021:1–9.

Vedelago L, Wardell J, Kempe T, Patel H, Amlung M, MacKillop J, et al. Getting high to cope with COVID-19: modelling the associations between cannabis demand, coping motives, and cannabis use and problems. Addict Behav. 2022;124:107092.

Imtiaz S, Wells S, Rehm J, Wickens CM, Hamilton H, Nigatu YT et al. Daily cannabis use during the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic in Canada: a repeated cross-sectional study from May 2020 to December 2020. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 2022;17(1):1–8.

Mravčík V, Chomynová P. Substance use and addictive behaviours during COVID-19 confinement measures increased in intensive users: results of an online general population survey in the Czech Republic. Epidemiologie, mikrobiologie, imunologie: casopis spolecnosti pro epidemiologii a mikrobiologii ceske lekarske spolecnosti. JE Purkyne. 2021;70(2):98–103.

Chaiton M, Dubray J, Kundu A, Schwartz R. Perceived impact of COVID on Smoking, Vaping, Alcohol and Cannabis Use among Youth and Youth adults in Canada. Can J Psychiatry. 2021:07067437211042132.

Dietz P, Werner AM, Reichel JL, Schäfer M, Mülder LM, Beutel M et al. The prevalence of pharmacological neuroenhancement among University students before and during the COVID-19-Pandemic: results of three consecutive cross-sectional Survey studies in Germany. Front Public Health. 2022:601.

Dumas TM, Ellis WE, Van Hedger S, Litt DM, MacDonald M. Lockdown, bottoms up? Changes in adolescent substance use across the COVID-19 pandemic. Addict Behav. 2022;131:107326.

Gritsenko V, Skugarevsky O, Konstantinov V, Khamenka N, Marinova T, Reznik A, et al. COVID 19 fear, stress, anxiety, and substance use among Russian and Belarusian university students. Int J Mental Health Addict. 2021;19(6):2362–8.

Mohr CD, Umemoto SK, Rounds TW, Bouleh P, Arpin SN. Drinking to cope in the COVID-19 era: an investigation among college students. J Stud Alcohol Drug. 2021;82(2):178–87.

Potvin J, Ramos Socarras L, Forest G. Sleeping through a lockdown: how adolescents and young adults struggle with lifestyle and sleep habits upheaval during a pandemic. Behav Sleep Med. 2022:1–17.

Reuter PR, Forster BL, Kruger BJ. A longitudinal study of the impact of COVID-19 restrictions on students’ health behavior, mental health and emotional well-being. PeerJ. 2021;9:e12528.

Romm KF, Patterson B, Arem H, Price OA, Wang Y, Berg CJ. Cross-sectional retrospective assessments versus longitudinal prospective assessments of substance use change among young adults during COVID-19: magnitude and correlates of discordant findings. Subst Use Misuse. 2022;57(3):484–9.

Schepis TS, De Nadai AS, Bravo AJ, Looby A, Villarosa-Hurlocker MC, Earleywine M, et al. Alcohol use, cannabis use, and psychopathology symptoms among college students before and after COVID-19. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;142:73–9.

Sharma P, Ebbert JO, Rosedahl JK, Philpot LM. Changes in substance use among young adults during a Respiratory Disease pandemic. SAGE Open Medicine. 2020;8:2050312120965321.

Tucker JS, D’Amico EJ, Pedersen ER, Garvey R, Rodriguez A, Klein DJ. Behavioral health and service usage during the COVID-19 pandemic among emerging adults currently or recently experiencing homelessness. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67(4):603–5.

Villanti AC, LePine SE, Peasley-Miklus C, West JC, Roemhildt M, Williams R, et al. COVID‐related distress, mental health, and substance use in adolescents and young adults. Child Adolesc Mental Health. 2022;27(2):138–45.

Firkey MK, Sheinfil AZ, Woolf-King SE. Substance use, sexual behavior, and general well-being of US college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a brief report. J Am Coll Health. 2020:1–7.

Miech R, Patrick ME, Keyes K, O’Malley PM, Johnston L. Adolescent drug use before and during US national COVID-19 social distancing policies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;226:108822.

Salmon S, Taillieu TL, Fortier J, Stewart-Tufescu A, Afifi TO. Pandemic-related experiences, mental health symptoms, substance use, and relationship conflict among older adolescents and young adults from Manitoba, Canada. Psychiatry Res. 2022;311:114495.

Studer J, Marmet S, Gmel G, Wicki M, Labhart F, Gachoud C et al. Changes in substance use and other reinforcing behaviours during the COVID-19 crisis in a general population cohort study of young Swiss men. J Behav Addictions. 2021.

Tham SW, Murray CB, Law EF, Slack KE, Palermo TM. The impact of the coronavirus Disease 2019 pandemic on pain and psychological functioning in young adults with chronic pain. Pain. 2022:101097.

Lukács A. Mental well-being of university students in social isolation. Eur J Health Psychol. 2021.

Terry-McElrath YM, O’Malley PM, Pang YC, Patrick ME. Characteristics and reasons for use associated with solitary alcohol and marijuana use among US 12th Grade students, 2015–2021. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;235:109448.

von Soest T, Kozák M, Rodríguez-Cano R, Fluit DH, Cortés-García L, Ulset VS, et al. Adolescents’ psychosocial well-being one year after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in Norway. Nat Hum Behav. 2022;6(2):217–28.

Vidot DC, Islam JY, Camacho-Rivera M, Harrell MB, Rao DR, Chavez JV, et al. The COVID-19 cannabis health study: results from an epidemiologic assessment of adults who use cannabis for medicinal reasons in the United States. J Addict Dis. 2020;39(1):26–36.

Xuereb S, Kim HS, Clark L, Wohl MJ. Substitution behaviors among people who gamble during COVID-19 precipitated casino closures. Int Gambl Stud. 2021;21(3):411–25.

Baum MK, Tamargo JA, Diaz-Martinez J, Delgado-Enciso I, Meade CS, Kirk GD, et al. HIV, psychological resilience, and substance misuse during the COVID-19 pandemic: a multi-cohort study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;231:109230.

Camacho-Rivera M, Islam JY, Rodriguez DL, Vidot DC. Cannabis use among cancer survivors amid the COVID-19 pandemic: results from the COVID-19 cannabis health study. Cancers. 2021;13(14):3495.

Donovan KA, Portman DG. Effect OF COVID-19 pandemic on cannabis use in cancer patients. Am J Hospice Palliat Medicine®. 2021;38(7):850–3.

Hochstatter KR, Akhtar WZ, Dietz S, Pe-Romashko K, Gustafson DH, Shah DV, et al. Potential influences of the COVID-19 pandemic on drug use and HIV care among people living with HIV and substance use disorders: experience from a pilot mHealth intervention. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(2):354–9.

Meanley S, Choi SK, Thompson AB, Meyers JL, D’Souza G, Adimora AA, et al. Short-term binge drinking, marijuana, and recreational drug use trajectories in a prospective cohort of people living with HIV at the start of COVID-19 mitigation efforts in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;231:109233.

Baillie G, Peacock A, Hammoud M, Memedovic S, Barratt M, Bruno R et al. Key findings from the ‘Australians’ Drug Use: adapting to pandemic threats (ADAPT)’Study Wave 4. ADAPT Bulletin. 2021(4).

Carlyle M, Leung J, Walter ZC, Juckel J, Salom C, Quinn CA et al. Changes in Substance Use Among People Seeking Alcohol and Other Drug Treatment During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evaluating Mental Health Outcomes and Resilience. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment. 2021;15:11782218211061746.

Doherty L, Sullivan T, Voce A. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cannabis demand and supply in Australia. 2021.

EMCDDA. The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) European Web Survey on Drugs: Results.; 2022.

Manthey J, Kilian C, Carr S, Bartak M, Bloomfield K, Braddick F et al. Use of alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, and other substances during the first wave of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in Europe: a survey on 36,000 European substance users. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 2021;16(1):1–11.

Palamar JJ, Le A, Acosta P. Shifts in drug use behavior among electronic dance music partygoers in New York during COVID-19 social distancing. Subst Use Misuse. 2020;56(2):238–44.

Scherbaum N, Bonnet U, Hafermann H, Schifano F, Bender S, Grigoleit T et al. Availability of illegal Drugs during the CoViD-19 pandemic in western Germany. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12.

Pavarin RM, Bettelli S, Nostrani E, Mazzotta C, Salsano V, Ulgheri AL, et al. Substance consumption styles during the COVID-19 lockdown for socially integrated people who use Drugs. J Subst Use. 2022;27(2):218–23.

Sande M, Šabić S, Paš M, Verdenik M. How has the COVID-19 Epidemic Changed Drug Use and the Drug Market in Slovenia? Društvena istraživanja. 2021;30(2):313–32.

Conroy DA, Hadler NL, Cho E, Moreira A, MacKenzie C, Swanson LM, et al. The effects of COVID-19 stay-at-home order on sleep, health, and working patterns: a survey study of US health care workers. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17(2):185–91.

Weyandt LL, Francis A, Shepard E, Gudmundsdóttir BG, Channell I, Beatty A, et al. Anxiety, depression, impulsivity, and mindfulness among higher education faculty during covid-19. Health Behav Policy Rev. 2020;7(6):532–45.

Mora AM, Lewnard JA, Kogut K, Rauch S, Morga N, Jewell N et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and vaccine hesitancy among farmworkers from Monterey County, Calif medRxiv. 2020.

Reilly ED, Chamberlin ES, Duarte BA, Harris JI, Shirk SD, Kelly MM. The impact of COVID-19 on Self-reported Substance Use, Well-Being, and functioning among United States veterans: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychol. 2022;13:812247.

Fitzke RE, Wang J, Davis JP, Pedersen ER. Substance use, depression, and loneliness among American veterans during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Addictions. 2021;30(6):552–9.

Janulis P, Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Decrease in prevalence but increase in frequency of non-marijuana drug use following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in a large cohort of young men who have sex with men and young transgender women. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;223:108701.

Starks TJ, Jones SS, Sauermilch D, Benedict M, Adebayo T, Cain D, et al. Evaluating the impact of COVID-19: a cohort comparison study of drug use and risky sexual behavior among sexual minority men in the USA. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;216:108260.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This project was funded by an Ontario HIV Treatment Network Breaking New Ground Grant. Sergio Rueda is supported by an Ontario HIV Treatment Network Endgame Innovator Award.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: SR; Methodology: KM, JR, JLW, TMW, SB, SR; Search Strategy: SB; Software: KM, JR, SB; Validation: KM, JR, JLW, TMW, SB, SR; Analysis: KM, JR; Investigation: KM, JR, JLW, TMW, SB, SR; Data Curation: KM, JR; Writing: Original Draft Preparation, KM; Writing: Review & Editing, KM, JR, JLW, TMW, SB, SR. Supervision: SR; Project Administration: KM, JR, JLW, TMW, SB, SR. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Mehra, K., Rup, J., Wiese, J.L. et al. Changes in self-reported cannabis use during the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review. BMC Public Health 23, 2139 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-17068-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-17068-7