Abstract

Background

This study examined whether heavy episodic drinking (HED), cannabis use, and subjective changes in alcohol and cannabis use during the COVID-19 pandemic differ between transgender and gender-diverse (TGD) and cisgender adults.

Methods

Successive waves of web-based cross-sectional surveys. Setting: Canada, May 2020 to March 2021. Participants: 6,016 adults (39 TGD, 2,980 cisgender men, 2,984 cisgender women, and 13 preferred not to answer), aged ≥18 years. Measurements: Measures included self-reported HED (≥5 drinks on one or more occasions in the previous week for TGD and cisgender men and ≥4 for cisgender women) and any cannabis use in the previous week. Subjective changes in alcohol and cannabis use in the past week compared to before the pandemic were measured on a five-point Likert scale (1: much less to 5: much more). Binary and ordinal logistic regressions quantified differences between TGD and cisgender participants in alcohol and cannabis use, controlling for age, ethnoracial background, marital status, education, geographic location, and living arrangement.

Results

Compared to cisgender participants, TGD participants were more likely to use cannabis (adjusted odds ratio (aOR)=3.78, 95%CI: 1.89, 7.53) and to have reported subjective increases in alcohol (adjusted proportional odds ratios (aPOR)= 2.00, 95%CI: 1.01, 3.95) and cannabis use (aPOR=4.56, 95%CI: 2.13, 9.78) relative to before the pandemic. Compared to cisgender women, TGD participants were more likely to use cannabis (aOR=4.43, 95%CI: 2.21, 8.87) and increase their consumption of alcohol (aPOR=2.05, 95%CI: 1.03, 4.05) and cannabis (aPOR=4.71, 95%CI: 2.18, 10.13). Compared to cisgender men, TGD participants were more likely to use cannabis (aOR=3.20, 95%CI: 1.60, 6.41) and increase their use of cannabis (aPOR=4.40, 95%CI: 2.04, 9.49). There were no significant differences in HED between TGD and cisgender participants and in subjective change in alcohol between TGD and cisgender men; however, the odds ratios were greater than one as expected.

Conclusions

Increased alcohol and cannabis use among TGD populations compared to before the pandemic may lead to increased health disparities. Accordingly, programs targeting the specific needs of TGD individuals should be prioritized.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Disparities in substance use and resulting harms between transgender and gender-diverse (TGD) people (i.e., individuals whose gender identity differs from societal expectations based on their sex assigned at birth) and cisgender people (i.e., individuals whose gender identity aligns with their sex assigned at birth) are well-established [1,2,3,4,5]. Such disparities are due, in part, to TGD individuals having an elevated risk of experiencing mental health problems [5,6,7], resulting from stigma, discrimination, and violence [8,9,10].

The COVID-19 pandemic has heightened mental health problems and reduced resilience to chronic stressors among TGD individuals due to delays in providing gender-affirming services, including gender-affirming interventions (e.g., transition-related surgeries, hormone therapy), and to reduced access to TGD support groups [11,12,13]. Substance use (i.e., alcohol drinking and cannabis use) may represent a coping strategy in response to elevated mental health problems [14,15,16,17]. This may result in acute and chronic harms, such as injury, substance use dependence, and death [18,19,20,21]. A better understanding of alcohol and cannabis use among TGD people during the pandemic is needed to inform public health interventions since TGD people may be more vulnerable to pandemic harms.

Recent research on the general population has shown an increase in alcohol [22,23,24,25] and cannabis [22, 26, 27] use during the pandemic, and that people experiencing high levels of mental health symptoms may be at risk of using substances [28, 29]. This pattern may have increased substance-related hospitalizations and deaths during the pandemic – in Canada, between March and September 2020, hospitalizations and deaths due to substance use increased by 5% and 13% compared to the same period in 2019 [30]. These increases are a pressing concern for the government and public health authorities working on a national recovery plan in response to the COVID-19 pandemic [31, 32]. Additionally, more national data on population health behaviours, such as substance use, are needed to address the needs of the total population [32], including more vulnerable subgroups [33]

Despite the disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of TGD people (compared to cisgender) [34,35,36], little research has examined the differential impacts of the pandemic on substance use among TGD versus cisgender individuals. There is a need for more research on this topic to build programs targeting the specific needs of TGD people in response to COVID-19 [37, 38]. Accordingly, this study aimed to assess differences between TGD and cisgender Canadian adults in their respective alcohol and cannabis use during the COVID-19 pandemic. To achieve our objective, we used repeat cross-sectional surveys conducted in Canada examining the impact of COVID-19 on mental health and substance use.

Methods

Participants

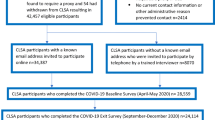

Data were obtained from seven successive Canada-wide cross-sectional web-based surveys of English-speaking Canadian adults aged ≥18 years. Survey data were collected by Delvinia using a proportional quota sampling methodology to approximate the English speaking population of Canada by age, sex, and region [39]. The surveys were conducted from May 2020 to March 2021: May 8-12, 2020 (Wave 1, n=1,005, response rate (RR)=15.9%), May 29-June 1, 2020 (Wave 2, n=1,002, RR=17.2%), June 19-23, 2020 (Wave 3, n=1,005, RR=16.4%), July 10-14, 2020 (Wave 4, n=1,003, RR=13.7%), September 18-22, 2020 (Wave 5, n=1,003, RR=17.6%), November 27-December 1, 2020 (Wave 6, n=1,003, RR=16.2%), and March 19-23, 2021 (Wave 7, n=1000, RR=15.8% (details of RR calculations are in Table S1 of the supplement). A pooled sample of 6,016 participants (Waves 2-7) was analyzed in this study. The questionnaires and data collected are provided in additional files. Wave 1 data were excluded as changes in alcohol and cannabis use were not measured for people who did not report drinking and cannabis use in the past week. The study received approval from the Research Ethics Board at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

Measures

Gender identity was assessed using the question: “How do you describe your gender identity?” Response options included: “Man,” “Woman,” “Transgender man,” “Transgender woman,” “Two-Spirit,” “Non-binary (genderqueer, gender fluid),” “Questioning/Not sure of my gender identity,” “Identity not listed,” and “Prefer not to answer.” Individuals who self-identified as a man or woman were categorized as cisgender. Individuals who self-identified as transgender, two-spirit, or non-binary and those who selected “Questioning/Not sure of my gender identity” or did not find their gender listed were categorized as TGD. Due to sample size limitations, TGD sub-identities (e.g., transgender man, transgender woman, gender non-binary) were aggregated into one category [40,41,42]. Participants who responded “prefer not to answer” were excluded from the main analysis. This measure of gender identity may lead to misclassification as TGD participants who self-identified as a man or woman would have been classified as cisgender rather than TGD. We acknowledged that this limitation of the survey could potentially reduce the number of TGD in the sample. An alternative to accurately identify TGD persons in population-based surveys would be, for example, asking two separate questions (i.e., one for current gender identity and another for birth-assigned sex) [43,44,45].

Heavy episodic drinking (HED) was assessed using the question: “On how many of the past seven days did you drink five/four or more drinks on one occasion?” Cisgender men and TGD participants were asked about ≥5 standard drinks (≥68.0 grams of alcohol) and cisgender women were asked about ≥4 standard drinks (≥54.4 grams of alcohol). We used “5 or more” drinks on one occasion to screen TGD people for heavy drinking as recommended in a recent US study [46]. HED was defined as engaging in at least one HED occasion in the past 7 days. Subjective changes in alcohol use were assessed through the question: “In the past 7 days, did you drink more alcohol, about the same, or less alcohol overall than you did before the COVID-19 pandemic started?” Response options were: 1 (much less), 2 (slightly less), 3 (no change), 4 (slightly more), and 5 (much more).

Cannabis use was derived from the question: “During the past 7 days, on how many days did you use cannabis?” A binary variable was created to reflect any cannabis use (use on one or more days) in the past week versus no cannabis use. Subjective changes in cannabis use were assessed with the question: “In the past 7 days, did you use cannabis more often, about the same, or less often overall than you did before the COVID-19 pandemic started?” As was the case for changes in alcohol use, response options ranged from 1: much less to 5: much more.

The following individual and household covariates were included as confounders in all analyses: age groups (18-39, 40-59, and 60 years or more), ethnoracial background (White, Asian, Black/Indigenous/Arab/Latino, and other ethnicities), marital status (married/living with partner, separated/divorced/widowed, and single), education (high school or less, some post-secondary, college degree, and university degree), geographic location (urban, suburban, and rural), having children under 18 in the household, and whether or not a participant lived with others.

Statistical analyses

In order to ascertain whether an association existed between gender identity and alcohol/cannabis use during the COVID-19 pandemic, multivariate logistic regression models were used for binary dependent variables (i.e., HED and cannabis use), and ordinal logistic regression models were used for ordinal response variables (i.e., subjective changes in alcohol and cannabis use). Adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and adjusted proportional odds ratios (aPORs) were reported for logistic and ordinal regression models, respectively, adjusting for the above-mentioned covariates. To compare TGD and cisgender individuals in terms of their respective alcohol and cannabis use, alternating reference groups for gender were used in three sets of regression models; that is, TGD participants were compared to: 1) all cisgender participants (both men and women), 2) cisgender men, and 3) cisgender women. Stata (version 16.0) was used for all analyses.

Results

A total of 39 of 6,003 (0.7%) participants self-identified as TGD, 2,980 (49.6%) as cisgender men, and 2,980 (49.7%) as cisgender women. The TGD group was composed of eight transgender men, four transgender women, eleven two-spirits, nine non-binary (genderqueer and gender fluid), five participants selected “questioning/Not sure of my gender identity”, and two participants did not find their gender listed. Note that in Canada, the estimated percentage of the transgender population, including non-binary individuals, was 0.35% in 2019 [47]. We excluded thirteen participants for not answering the gender identity question. Table 1 presents the distribution of participants’ self-reported consumption of alcohol and cannabis, as well as their socio-demographic characteristics.

Table 2 presents the adjusted aORs and aPORs for the associations between gender and HED, cannabis use, and subjective changes in alcohol and cannabis use (Tables S2-S4 in the supplement present information regarding all parameters included in the regression models). No significant differences in HED were observed between the TGD group and cisgender participants (both women and men), cisgender men, and cisgender women; however, the odds ratios were greater than one as expected. TGD participants had higher odds of using cannabis at least once a week (aOR=3.78, 95%CI: 1.89, 7.53) relative to cisgender participants. Similar results were observed when TGD participants were compared to cisgender women (aOR=4.43, 95%CI: 2.21, 8.87) and men (aOR=3.20, 95%CI: 1.60, 6.41). Regarding subjective changes in alcohol and cannabis use compared to before the pandemic, the results showed that TGD participants were at greater odds of reporting subjective increases in their alcohol consumption (i.e., drinking much or slightly more versus no change, slightly less, or much less) relative to cisgender men and women combined (aPOR=2.00, 95%CI: 1.01, 3.95) and cisgender women (aPOR=2.05, 95%CI: 1.03, 4.05). Although the aPOR was greater than one when comparing TGD group to cisgender men regarding subjective changes in alcohol use, it was not statistically significant at 5% level. The TGD group was also at higher odds of reporting an increase in cannabis use than cisgender women and men combined (aPOR=4.56, 95%CI: 2.13, 9.78), cisgender women (aPOR=4.71, 95%CI: 2.18, 10.13), and cisgender men (aPOR=4.40, 95%CI: 2.04, 9.49).

Participants who did not respond to the question on gender identity were excluded from the above results (13 participants were excluded). These participants were added into the TGD subsample to conduct a sensitivity analysis. Qualitatively similar results were observed when compared to the main findings (see Table S5 in the supplement).

Discussion

This study assessed disparities in HED, cannabis use, and subjective alcohol and cannabis use changes during the COVID-19 pandemic between TGD and cisgender participants. Results showed no significant differences in HED between TGD and any of the cisgender groups (i.e., both cisgender men and women, cisgender men or cisgender women), but interestingly the corresponding odds ratios were greater than one as expected. For all comparisons, TGD participants had higher odds of using cannabis. The results also revealed that TGD participants had a higher likelihood of reporting subjective increases in their use of cannabis since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, compared with cisgender men and women combined, cisgender men, and cisgender women. Additionally, TGD participants were more likely to report subjective increases in their alcohol use during the pandemic than cisgender men and women combined and cisgender women. When compared to cisgender men, the proportional odds ratio of subjective change in alcohol was greater than one but not statistically significant.

These findings should be considered in the context of several limitations. First, the study used a non-probabilistic sample drawn from English-speaking Canadians, and therefore may not be generalizable to the Canadian population. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the study does not allow for causal inference. Third, the relatively small number of TGD respondents prevents the exploration of heterogeneity among TGD subgroups [48,49,50,51] and issues of intersectionality. It also resulted in wide confidence intervals for some estimates, thereby making the findings somewhat tentative. The measurement of gender identity in this survey may have impacted the number of TGD respondents. The gender identity question response options may not encompass all gender identities. To accurately classify transgender individuals, experts recommend including a second question measuring sex assigned at birth (i.e., "male" or "female") [44, 45], which was not done in this study. Therefore, some participants may have been grouped incorrectly. Finally, some individuals who do not identify as TGD may have been categorized as such, since those who selected: “Questioning/Not sure of my gender identity” and “Identity not listed” were included in the TGD group. Nevertheless, this preliminary and suggestive study offers useful insights into better understanding disparities in substance use between cisgender and TGD populations during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our study’s findings are in line with recently published paper using data on Canadian adults [52] and previous research that reported increased risks for harmful drinking and HED [2, 4, 48, 49, 53, 54], and cannabis use [4, 49, 55] among TGD people, relative to their cisgender counterparts. These findings may be partially explained by social stigma and discrimination experienced by TGD individuals, resulting in heightened levels of stress, which may be heightened even further during the pandemic [56]. High levels of stress have been found to be associated with alcohol [57,58,59] and cannabis use [60,61,62]. Particularly, among TGD individuals, high levels of physical and psychological gender-related abuse have been associated with higher odds of alcohol and cannabis use [63, 64].

This study found that TGD participants increased their consumption of alcohol and cannabis during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to cisgender participants. These results are consistent with the fact that the implemented lockdown orders have exacerbated mental health symptoms among individuals [65,66,67,68,69], leading to more consumption of alcohol [22,23,24,25] and cannabis [22, 26]. The pandemic has exacerbated ongoing mental health disparities for TGD individuals [11, 12, 52, 70] due to reduced access to gender-affirming healthcare and treatment (as non-essential services) and the resulting increased psychological distress [11, 71]. This may have led to an increase in alcohol and cannabis use in TGD populations.

Conclusions

We identified disparities in HED, cannabis use, and subjective changes in alcohol and cannabis use during the COVID-19 pandemic between TGD and cisgender Canadian adults. Although our study highlights some differences in alcohol and cannabis use during the COVID-19 pandemic between TGD and cisgender people, more research is needed to fully understand disparities in substance use between TGD individuals and cisgender individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic. This will require collecting more data among TGD subgroups (i.e., transgender men, transgender women, two-spirit, and non-binary individuals). Identifying subgroups of TGD individuals at high-risk of engaging in substance use and misuse during the COVID-19 pandemic, and prioritizing gender-affirming medical and mental health care when reopening deferred services, are particularly important to increase general wellbeing among TGD individuals during and after the pandemic.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files]. Data are also publicly available for download at: http://www.delvinia.com/coronavirus/.

Abbreviations

- HED:

-

Heavy episodic drinking

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- TGD:

-

Transgender and gender-diverse

- aOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- aPOR:

-

Adjusted proportional odds ratios

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- RR:

-

Response rate

References

Gilbert PA, Pass LE, Keuroghlian AS, Greenfield TK, Reisner SL. Alcohol research with transgender populations: A systematic review and recommendations to strengthen future studies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;186:138–46.

Scheim AI, Bauer GR, Shokoohi M. Heavy episodic drinking among transgender persons: Disparities and predictors. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;167:156–62.

Newcomb ME, Hill R, Buehler K, Ryan DT, Whitton SW, Mustanski B. High Burden of Mental Health Problems, Substance Use, Violence, and Related Psychosocial Factors in Transgender, Non-Binary, and Gender Diverse Youth and Young Adults. Arch Sex Behav. 2020;49(2):645–59.

Day JK, Fish JN, Perez-Brumer A, Hatzenbuehler ML, Russell ST. Transgender Youth Substance Use Disparities: Results From a Population-Based Sample. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2017;61(6):729–35.

Lowry R, Johns MM, Gordon AR, Austin SB, Robin LE, Kann LK. Nonconforming Gender Expression and Associated Mental Distress and Substance Use Among High School Students. JAMA Pediatrics. 2018;172(11):1020–8.

Abramovich A, de Oliveira C, Kiran T, Iwajomo T, Ross LE, Kurdyak P. Assessment of Health Conditions and Health Service Use Among Transgender Patients in Canada. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(8):e2015036-e.

Dhejne C, Van Vlerken R, Heylens G, Arcelus J. Mental health and gender dysphoria: A review of the literature. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2016;28(1):44–57.

Winter S, Diamond M, Green J, Karasic D, Reed T, Whittle S, et al. Transgender people: health at the margins of society. Lancet. 2016;388(10042):390–400.

Abramovich A, Lam JSH, Chowdhury M. A transgender refugee woman experiencing posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and homelessness. Cmaj. 2020;192(1):E9-e11.

Reisner SL, Poteat T, Keatley J, Cabral M, Mothopeng T, Dunham E, et al. Global health burden and needs of transgender populations: a review. Lancet. 2016;388(10042):412–36.

Kidd JD, Jackman KB, Barucco R, Dworkin JD, Dolezal C, Navalta TV, et al. Understanding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of transgender and gender nonbinary individuals engaged in a longitudinal cohort study. J Homosex. 2021;68(4):592–611.

Koehler A, Motmans J, Alvarez LM, Azul D, Badalyan K, Basar K, et al. How the COVID-19 pandemic affects transgender health care in upper-middle-income and high-income countries – A worldwide, cross-sectional survey. medRxiv. 2020:2020.12.23.20248794.

Woulfe J, Wald M. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Transgender and Non-Binary Community 2020 [Available from: https://www.columbiapsychiatry.org/news/impact-covid-19-pandemic-transgender-and-non-binary-community.

Capasso A, Jones AM, Ali SH, Foreman J, Tozan Y, DiClemente RJ. Increased alcohol use during the COVID-19 pandemic: The effect of mental health and age in a cross-sectional sample of social media users in the US. Prev Med. 2021;145:106422.

Avery AR, Tsang S, Seto EYW, Duncan GE. Stress, Anxiety, and Change in Alcohol Use During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Findings Among Adult Twin Pairs. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:571084. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.571084.

Michelle R. Canadians who report lower self-perceived mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic more likely to report increased use of cannabis, alcohol and tobacco. In: Canada S, editor. StatCan COVID-19: Data to Insights for a Better Canada. Ottawa: Government of Canada; 2020.

Li Q, Li X, Stanton B. Alcohol use among female sex workers and male clients: an integrative review of global literature. Alcohol Alcohol. 2010;45(2):188–99.

Rehm J, Shield KD. Global alcohol-attributable deaths from cancer, liver cirrhosis, and injury in 2010. Alcohol Res. 2013;35(2):174–83.

Lachenmeier DW, Monakhova YB, Rehm J. Influence of unrecorded alcohol consumption on liver cirrhosis mortality. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(23):7217–22.

Connor J, Casswell S. Alcohol-related harm to others in New Zealand: evidence of the burden and gaps in knowledge. N Z Med J. 2012;125(1360):11–27.

Crocker CE, Carter AJE, Emsley JG, Magee K, Atkinson P, Tibbo PG. When cannabis use goes wrong: mental health side effects of cannabis use that present to emergency services. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:640222.

Vanderbruggen N, Matthys F, Van Laere S, Zeeuws D, Santermans L, Van den Ameele S, et al. Self-Reported Alcohol, Tobacco, and Cannabis Use during COVID-19 Lockdown Measures: Results from a Web-Based Survey. Basel: European Addiction Research; 2020.

Jernigan DH. America is Drinking Its Way through the Coronavirus Crisis—That Means More Health Woes Ahead. Available online: https://theconversation.com/america-is-drinking-its-way-ugh-the-coronavirus-crisis-that-means-more-health-woes-ahead-135532. Accessed 20 Feb 2022.

Finlay I, Gilmore I. Covid-19 and alcohol—a dangerous cocktail. BMJ. 2020;369:m1987.

Ahmed MZ, Ahmed O, Aibao Z, Hanbin S, Siyu L, Ahmad A. Epidemic of COVID-19 in China and associated psychological problems. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102092.

Bartel SJ, Sherry SB, Stewart SH. Self-isolation: A significant contributor to cannabis use during the COVID-19 pandemic. Subst Abus. 2020;41(4):409-12. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2020.1823550.

Imtiaz S, Wells S, Rehm J, Hamilton HA, Nigatu YT, Wickens CM, Jankowicz D, Elton-Marshall T. Cannabis Use During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Canada: A Repeated Cross-sectional Study. J Addict Med. 2021;15(6):484-90. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000798.

Gorka SM, Hedeker D, Piasecki TM, Mermelstein R. Impact of alcohol use motives and internalizing symptoms on mood changes in response to drinking: An ecological momentary assessment investigation. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;173:31–8.

Foster DW, Buckner JD, Schmidt NB, Zvolensky MJ. Multisubstance Use Among Treatment-Seeking Smokers: Synergistic Effects of Coping Motives for Cannabis and Alcohol Use and Social Anxiety/Depressive Symptoms. Subst Use Misuse. 2016;51(2):165–78.

Public Health Agency of Canada. Wider impacts of COVID-19: A look at how substance-related harms across Canada have changed during the pandemic 2021 [Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/covid-19-substance-related-harms-infographic.html.

Government of Canada. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Canada’s response 2020 [updated November 30, 2021. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/canadas-reponse.html#hps.

Varin M, Hill MacEachern K, Hussain N, Baker MM. Measuring self-reported change in alcohol and cannabis consumption during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2021;41(11):325–30.

Evans AC, Bufka LF. The critical need for a population health approach: addressing the nation’s behavioral health during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2020;17:E79.

Moore SE, Wierenga KL, Prince DM, Gillani B, Mintz LJ. Disproportionate Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on perceived social support, mental health and somatic symptoms in sexual and gender minority populations. J Homosex. 2021;68(4):577–91.

Brennan DJ, Card KG, Collict D, Jollimore J, Lachowsky NJ. How Might Social Distancing Impact Gay, Bisexual, Queer, Trans and Two-Spirit Men in Canada? AIDS and Behavior. 2020;24(9):2480–2.

Phillips Ii G, Felt D, Ruprecht MM, Wang X, Xu J, Pérez-Bill E, et al. Addressing the Disproportionate Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Sexual and Gender Minority Populations in the United States: Actions Toward Equity. LGBT Health. 2020;7(6):279–82.

Gorczynski P, Fasoli F. LGBTQ+ focused mental health research strategy in response to COVID-19. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(8):e56-e.

Salerno JP, Devadas J, Pease M, Nketia B, Fish JN. Sexual and Gender Minority Stress Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: Implications for LGBTQ Young Persons’ Mental Health and Well-Being. Public Health Reports. 2020;135(6):721–7.

Callegaro M, DiSogra C. Computing response metrics for online panels. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2008;72(5):1008–32.

Hinds JT, Loukas A, Perry CL. Sexual and gender minority college students and tobacco use in Texas. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2017;20(3):383–7.

Roxburgh A, Lea T, de Wit J, Degenhardt L. Sexual identity and prevalence of alcohol and other drug use among Australians in the general population. Int J Drug Policy. 2016;28:76–82.

Thrul J, Lisha NE, Ling PM. Tobacco marketing receptivity and other tobacco product use among young adult bar patrons. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59(6):642–7.

Tate CC, Ledbetter JN, Youssef CP. A two-question method for assessing gender categories in the social and medical sciences. J Sex Res. 2013;50(8):767–76.

Reisner SL, Biello K, Rosenberger JG, Austin SB, Haneuse S, Perez-Brumer A, et al. Using a two-step method to measure transgender identity in latin America/the Caribbean, Portugal, and Spain. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2014;43(8):1503–14.

Lagos D, Compton DL. Evaluating the use of a two-step gender identity measure in the 2018 general social survey. Demography. 2021;58(2):763–72.

Flentje A, Barger BT, Capriotti MR, Lubensky ME, Tierney M, Obedin-Maliver J, et al. Screening gender minority people for harmful alcohol use. PloS One. 2020;15(4):e0231022-e.

Statistics Canada. Sex at birth and gender: Technical report on changes for the 2021 Census. 2020 [updated July 20, 2020. Available from: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/ref/98-20-0002/982000022020002-eng.cfm.

Azagba S, Latham K, Shan L. Cigarette, smokeless tobacco, and alcohol use among transgender adults in the United States. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;73:163–9.

Connolly D, Davies E, Lynskey M, Barratt MJ, Maier L, Ferris J, et al. Comparing intentions to reduce substance use and willingness to seek help among transgender and cisgender participants from the global drug survey. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2020;112:86–91.

Gonzalez CA, Gallego JD, Bockting WO. Demographic characteristics, components of sexuality and gender, and minority stress and their associations to excessive alcohol, cannabis, and illicit (Noncannabis) drug use among a large sample of transgender people in the United States. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2017;38(4):419–45.

Kidd JD, Levin FR, Dolezal C, Hughes TL, Bockting WO. Understanding predictors of improvement in risky drinking in a US multi-site longitudinal cohort study of transgender individuals: Implications for culturally-tailored prevention and treatment efforts. Addict Behav. 2019;96:68–75.

Slemon A, Richardson C, Goodyear T, Salway T, Gadermann A, Oliffe JL, et al. Widening mental health and substance use inequities among sexual and gender minority populations: Findings from a repeated cross-sectional monitoring survey during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada. Psychiatry Research. 2022;307:114327.

Staples JM, Neilson EC, George WH, Flaherty BP, Davis KC. A descriptive analysis of alcohol behaviors across gender subgroups within a sample of transgender adults. Addict Behav. 2018;76:355–62.

Tupler LA, Zapp D, DeJong W, Ali M, O’Rourke S, Looney J, et al. Alcohol-related blackouts, negative alcohol-related consequences, and motivations for drinking reported by newly matriculating transgender college students. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2017;41(5):1012–23.

Denson DJ, Padgett PM, Pitts N, Paz-Bailey G, Bingham T, Carlos JA, McCann P, Prachand N, Risser J, Finlayson T. Health Care Use and HIV-Related Behaviors of Black and Latina Transgender Women in 3 US Metropolitan Areas: Results From the Transgender HIV Behavioral Survey. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;75(Suppl 3):S268-S275. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000001402.

Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(5):674–97.

José BS, VanOers Ham, De VanMheen HD, Garretsen HFL, Mackenbach JP. Stressors and alcohol consumption. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2000;35(3):307–12.

Kim S, Ades M, Pinho V, Cournos F, McKinnon K. Patterns of HIV and mental health service integration in New York State. AIDS Care. 2014;26(8):1027–31.

Yoon SJ, Kim HJ, Doo M. Association between perceived stress, alcohol consumption levels and obesity in Koreans. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2016;25(2):316–25.

Hyman SM, Sinha R. Stress-related factors in cannabis use and misuse: implications for prevention and treatment. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 2009;36(4):400–13.

Temple EC, Driver M, Brown RF. Cannabis use and anxiety: is stress the missing piece of the puzzle? Frontiers in psychiatry. 2014;5:168.

Cuttler C, Spradlin A, McLaughlin RJ. A naturalistic examination of the perceived effects of cannabis on negative affect. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2018;235:198–205.

Nuttbrock L, Bockting W, Rosenblum A, Hwahng S, Mason M, Macri M, et al. Gender abuse, depressive symptoms, and substance use among transgender women: a 3-year prospective study. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(11):2199–206.

Wolf ECM, Dew BJ. Understanding Risk Factors Contributing to Substance Use Among MTF Transgender Persons. J LGBTQ Issues Couns. 2012;6(4):237–56.

Domènech-Abella J, Mundó J, Haro JM, Rubio-Valera M. Anxiety, depression, loneliness and social network in the elderly: Longitudinal associations from The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA). J Affect Disord. 2019;246:82–8.

Calati R, Ferrari C, Brittner M, Oasi O, Olié E, Carvalho AF, et al. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors and social isolation: A narrative review of the literature. J Affect Disord. 2019;245:653–67.

Cacioppo JT, Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, Thisted RA. Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Psychol Aging. 2006;21(1):140–51.

Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–20.

Shigemura J, Ursano RJ, Morganstein JC, Kurosawa M, Benedek DM. Public responses to the novel 2019 coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Japan: Mental health consequences and target populations. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020;74(4):281–2.

van der Miesen AIR, Raaijmakers D, van de Grift TC. “You Have to Wait a Little Longer”: Transgender (Mental) Health at Risk as a Consequence of Deferring Gender-Affirming Treatments During COVID-19. Arch Sex Behav. 2020;49(5):1395–9.

Restar AJ, Jin H, Jarrett B, Adamson T, Baral SD, Howell S, et al. Characterising the impact of COVID-19 environment on mental health, gender affirming services and socioeconomic loss in a global sample of transgender and non-binary people: a structural equation modelling. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(3):e004424.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the in-kind support for data collection by Delvinia.

Funding

Delvinia, a research technology firm provided in-kind support for data collection. We did not receive funding from Delvinia, however, they have administered our questionnaires to Canadians through their web-based panel AskingCanadians (http://www.delvinia.com/solutions/askingcanadians/), without charging any fees.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KS initiated the study. AA, MS, SW, KS, and NHS conceptualized and designed the study. HAH and TEM developed the survey questionnaires for the data collection. NHS analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. All co-authors read and critically revised successive drafts of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study has been granted ethics committee approval from the Research Ethics Board at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, ON, Canada. The Centre For Addiction and Mental Health Research Ethics Board (CAMH REB) operates in compliance with, and is constituted in accordance with, the requirements of the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (TCPS 2), the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice Consolidated Guideline (ICH GCP), Part C, Division 5 of the Food and Drug Regulations, Part 4 of the Natural Health Products Regulations, Part 3 of the Medical Devices Regulations, and the provisions of the Ontario Personal Health Information Protection Act (PHIPA 2004) and its applicable regulations. The CAMH REB is qualified through the CTO REB Qualification Program and is registered with the US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) Office for Human Research Protection (OHRP). All participants provided written consent to participate.

Consent for publication

N.A.

Competing interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Survey interviews information and response rate calculations. Table S2. Full estimation: Logistic and ordinal logistic regressions of heavy episodic drinking, cannabis use at least once a week, and change in alcohol and cannabis use on transgender and gender-diverse status with cisgender participants (both men and women) as reference group. Table S3. Full estimation: Logistic and ordinal logistic regressions of heavy episodic drinking, cannabis use at least once a week, and subjective change in alcohol and cannabis use on transgender and gender-diverse status with cisgender women as reference group. Table S4. Full estimation: Logistic and ordinal logistic regressions of heavy episodic drinking, cannabis use at least once a week, and subjective change in alcohol and cannabis use on transgender and gender-diverse status with cisgender men as reference group. Table S5. Sensitivity analysis: Logistic and ordinal logistic regressions of heavy episodic drinking, cannabis use at least once a week, and subjective change in alcohol and cannabis use on transgender or gender-diverse status with participants who did not answer the gender identity question. Table S6. Full estimation: Logistic and ordinal logistic regressions of heavy episodic drinking, cannabis use at least once a week, and subjective change in alcohol and cannabis use on transgender and gender-diverse status with cisgender participants (both men and women) as reference group. The six categories of age groups were used in this model. Table S7. Full estimation: Logistic and ordinal logistic regressions of heavy episodic drinking, cannabis use at least once a week, and subjective change in alcohol and cannabis use on transgender and gender-diverse status with cisgender women as reference group. The six categories of age groups were used in this model. Table S8. Full estimation: Logistic and ordinal logistic regressions of heavy episodic drinking, cannabis use at least once a week, and subjective change in alcohol and cannabis use on transgender and gender-diverse status with cisgender men as reference group. The six categories of age groups were used in this model.

Additional file 2.

Survey Questionnaire.

Additional file 3.

Survey data.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Somé, N.H., Shokoohi, M., Shield, K.D. et al. Alcohol and cannabis use during the COVID-19 pandemic among transgender, gender-diverse, and cisgender adults in Canada. BMC Public Health 22, 452 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12779-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12779-9