Abstract

Background

Cigarette smoking is one of the most preventable causes of morbidities and mortalities. Since 2005, the World Health Organization Framework Convention for Tobacco Control (WHO-FCTC) provides an efficient strategic plan for tobacco control across the world. Many countries in the world have successfully reduced the prevalence of cigarette smoking. However, in developing countries, the prevalence of cigarette smoking is mounting which signifies a need of prompt attention. This scoping review aims to explore the extent and nature of Smoking Cessation (SmC) interventions and associated factors in South Asian Region (SAR) by systematically reviewing available recently published and unpublished literature.

Methods

The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) framework frames the conduct of this scoping review.

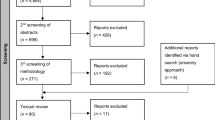

PubMed, EBSCO CINAHL Complete, Cochrane Library, ProQuest Dissertation and Theses, and local websites as well as other sources of grey literature were searched for relevant literature. In total, 573 literature sources were screened. Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram, finally, 48 data sources were included for data extraction and analysis.

We analyzed the extracted SmC interventions through the FCTC. Factors that affect smoking cessation interventions will be extracted through manual content analysis.

Results

Regarding FCTC recommended smoking cessation strategies (articles), most of the articles were either neglected or addressed in a discordant way by various anti-smoking groups in SAR. Key barriers that hamper the effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions included lack of awareness, poor implementation of anti-smoking laws, and socio-cultural acceptance of tobacco use. Conversely, increased levels of awareness, through different mediums, related to smoking harms and benefits of quitting, effective implementation of anti-smoking laws, smoking cessation trained healthcare professionals, support systems, and reluctance in the community to cigarette smoking were identified as facilitators to smoking cessation interventions.

Conclusion

The ignored or uncoordinated FCTC’s directions on smoking cessation strategies have resulted in continued increasing prevalence of cigarette smoking in developing countries, especially SAR. The findings of this review highlight the need for refocusing the smoking cessation strategies in SAR.

Strengths

The review was conducted by a team of expert comprising information specialists, and senior professors bringing rich experience in systematic and scoping reviews. Every effort was made to include all available literature sources addressing cigarette SmC and associated factors in SAR. The review findings signal the need and direction for more SmC efforts in SAR which may contribute to development of effective policies and guidelines for the control of smoking prevalence.

Limitations

Despite efforts, potentially relevant records may have been missed due to unpublished or inaccessible articles, unintended selection bias, or those published in local languages, etc. Moreover, the exclusion of literature on under 18 participants and mentally ill smokers may limit the generalizability of findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Tobacco-associated diseases are the first human-created global epidemic [1]. Tobacco use has resulted in 100 million lives lost in the twentieth century, with estimates of 1 billion more in the twenty-first century if the existing patterns of tobacco use remain unchanged [2]. More than 80% of the world’s tobacco users reside in developing countries like south Asian countries [3]. Tobacco use causes the death of 1.2 million people in SAR [4]. The updated data on prevalence of smoking in SAR were not found. However, according to data produced in 2009 and 2014, the burden of tobacco smoking among men was found 43% in Bangladesh, 42% in Maldives, 34.6% in India, 33% in Pakistan, 32% in Nepal, and 29% in Sri Lanka [4, 5]. Due to socio-cultural factors, the cigarette smoking prevalence is higher amongst men as compare to women in SAR except Nepal. In Nepal almost 26% amongst female smoke tobacco [4].

Cigarette smoking leads to detrimental health issues including cancer, cardiovascular, and pulmonary diseases [1] along with harmful effects of smoking on non-smokers [6]. Tobacco use contributes to poverty by usurping household expenses from basic needs like food, education, and shelter. Additionally, tobacco-associated diseases and deaths create economic damage due to healthcare costs and loss of human capital [3]. Individuals experiencing tobacco-related chronic health issues, mainly cancer, cardiovascular, and pulmonary diseases, are more motivated for smoking cessation (SmC) with an odds ratio ranging from 1.22 (95% CI 0.91–1.63) to 13.28 (95% CI 8.45–20.88) [7, 8].

Growing prevalence and consequences of smoking warrant attention to SmC. The World Health Assembly adopted the World Health Organization’s Framework Convention for Tobacco Control (WHO-FCTC) in 2003 with implementation in 2005. In 2018, FCTC was identified as an extensively adopted tobacco control framework amongst the United Nations signatories. The FCTC assists member countries in combating the tobacco epidemic through a comprehensive collection of evidence-based measures across a number of domains (e.g. reducing tobacco demand/supply) [9,10,11]. Through implementation of the main five [of 22] FCTC propositions (referred to as articles), one study found a significant (p-0.001) mean difference in smoking prevalence between 2005 and 2015 [12]. Hence, FCTC is a reliable framework to examine the level of initiatives taken by a country to reduce smoking prevalence. Several member countries have devised policies, laws, and guidelines to implement the FCTC articles and progress towards tobacco reduction targets. However, many low- and middle-income countries struggle with the effective and practical adaptation of FCTC, and are unlikely to achieve the target set by WHO that is 30% reduction in tobacco use by 2025 [11, 13].

Rationale

Ascertaining the effectiveness of similar SmC interventions in developed and developing countries has been challenging. Smoking cessation interventions, like anti-tobacco campaigns via mass media; increased cost of tobacco; widespread smoke-free regulations; accessible SmC support programs; and smoking health hazards warnings in films, have been effective in developed countries. The United States of America (USA) reduced smoking prevalence from 20.9 to 15.5% between 2005 and 2016; but the same trend has not been achieved in developing countries [8, 14, 15]. Countries in the South Asian Region (SAR) have utilized different SmC strategies; some are based on FCTC or MPOWER; others are unique to Asian cultural and societal norms.

Our search did not find any review conducted on a range of SmC interventions or facilitators and barriers to SmC in SAR. Reviews conducted in a specific country of SAR (e.g. India) included either trialed interventions or non-systematic search strategies that limited the inclusion of a broader range of available literature [16, 17].

Internationally, systematic reviews [18,19,20,21,22] and scoping reviews [23,24,25] have been limited to either inclusion of specific types of studies or to specific SmC interventions, often reflecting on technology based interventions, efficacy/effectiveness of interventions, or target populations for interventions. Clearly there is a lack of a unified range of SmC interventions and associated factors in literature from SAR.

Objectives

This scoping review explores the extent and nature of interventions for SmC in SAR by systematically reviewing available recently published and unpublished literature. It will seek factors that hinder or facilitate SmC interventions in SAR.

Methodology

This scoping review was registered with the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) register for systematic reviews page 10, dated 28th January 2020. Furthermore, the protocol for this review was published in the British Medical Journal Open (BMJ-Open) on January 2021 [26]. To ensure the inclusion of required components, we used Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist (please refer to Table 1).

As mentioned in the published protocol, we followed the JBI nine steps underpinned by the framework of Arksey and O’Malley in conducting this scoping review [27, 28]. For a detailed description of the JBI nine steps for scoping review, refer to our published protocol [26].

Literature search strategy and criteria for selection

We consulted an informational specialist [MK] respecting the selection of relevant databases and search terms. In December 2020, a systematic literature search was conducted across PubMed, EBSCO CINAHL Complete, Cochrane Library, and ProQuest Dissertation and Theses for the most recent 5 years of literature. The search was updated in June 2021 to include any additional publications to the databases (search strategy attached as supplementary material III). To enrich the extracted data, citation chaining was used to extract classic references from bibliographies of selected articles, and emailing authors of anti-smoking and/or anti-tobacco articles was also done. A grey literature search was conducted across the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADHT), Open Grey, Blogs, and local as well global websites. Details of the search terms, mesh words, Boolean operators, wildcards, and search syntaxes are provided in the published protocol [26].

We included all types of literature on interventions and barriers or facilitators to SmC relevant to the adult SAR population published in the last 5 years. Also, literature in English or any other language with English translation available were included. While studies including participants from countries other than SAR were excluded.

All relevant citations were imported to EndNote™ software. Two independent reviewers [SI and AK] read the titles and abstracts of the imported citations. Subfolders were developed in EndNote™ where the articles approved for full-text read were separated from those deemed irrelevant. The final inclusion of an article was decided after a full read and mutual agreement. Uncertainties encountered were discussed with supervisors [RR and PP].

Data extraction

The team developed separate templates in an Excel™ sheet for data extraction from empirical and non-empirical sources of literature. The empirical studies template extracted the study’s main characteristics like author/s name, year of publication, study settings, aim, design, framework or theory, population, smoking cessation interventions, barriers and/or facilitators, outcomes, limitations, and recommendations. From the non-empirical sources, the extracted characteristics included author/s, year of publication or the year of update, design /framework/ theory, study population, SmC interventions, barriers or facilitators to smoking cessation interventions, outcomes, limitations, or recommendations.

Data synthesis

Two reviewers [SI and AK] worked on data analysis and synthesis. The analysis plan was thoroughly discussed with systematic review experts (RB and PP). We also included critical feedback from another Ph.D. scholar and assistant professor [LL] on each step of the analysis. We used two approaches to make inferences about the extracted data. Smoking cessation interventions were analyzed through WHO-FCTC and SmC facilitators and barriers through manual content analysis.

We listed the FCTC articles 6–22 in a column. In the top row, the numbered coded studies were conscripted. We pooled the extracted interventions by aligning them with each relevant FCTC article and below the coded source of literature. We put a “+” or “-” symbol to simplify the data in a tabular form. Two main tables were developed for the SmC interventions; one reflected extractions from empirical sources while the second was from non-empirical sources.

Smoking cessation facilitators and barriers were copied to a Microsoft™ Word document. All barriers and facilitators were color-coded, similar or concomitant facilitators and barriers pooled into categories. Similarly, related categories were synthesized under broader themes.

Digressions from protocol

To include additional publications, we considered a second (updated) literature search in June 2021 at which time we included the EBSCO CINAHL Complete database instead of CINAHL and EBSCO Dentistry and Oral Sciences.

Patients and population involvement

There was no involvement of patients or the public in this study.

Results

After de-duplication, the search through databases and grey literature sources yielded 573 citations. As illustrated in Fig. 1, we had 284 citations after reviewing the titles and abstracts of the total citations. With full read, mutual agreement, and discussion with senior faculty members [RB & PP] 48 data sources were included comprised of 23 empirical and 25 non-empirical records.

Characteristics of included studies

The characteristics of included empirical studies are mentioned and attached as supplementary material-I. Of the 23 empirical records, most (13) were conducted in India, while one study was simultaneously conducted in two countries (Pakistan and Bangladesh). Table 2 provides the countries from which the data sources were traced.

Smoking cessation interventions

We analyzed the interventions extracted from both the empirical and non-empirical records through FCTC articles. Of the 22 FCTC strategies (which are called articles), the initial five articles are introductory to the framework while article seven pertains to articles eight to thirteen. Hence, we aligned the extracted interventions with the remaining 16 FCTC articles.

The focus of 73.9% of the empirical studies conducted in SAR in the past 5 years has been on education, communication, training, and public awareness (FCTC article 12). Similarly, 65.2% of the studies are aligned with the focus of article 14 which is demand reduction that includes clinical strategies to facilitate SmC, reduce smoking dependence, and control smoking at institutional levels. Moreover, 52% of the empirical records have been on the protection of tobacco smoke exposure including awareness of smoking health hazards as well as policies and regulations related to smoking-free spaces. Conversely, no empirical records focused on measures related to tobacco price and taxation, regulation of tobacco products, packaging and labeling, illegal trade of tobacco products, cigarettes sale to and by underage, economic alternatives for tobacco workers, protection of environment and health, and reporting and exchange of information. The details pertinent to SmC interventions extracted from empirical records and aligned with FCTC articles appear in Table 3.

Amongst the 25 non-empirical records, 80% addressed tobacco smoke protection that comprises awareness of smoking health hazards and regulations of policies related to smoke-free spaces (article 8). Similarly, 80% of the records mentioned FCTC article 13 which highlights the importance of working on controlling promotion, advertisement, and sponsorship of tobacco. Moreover, tobacco product packaging and labeling (FCTC article 11) is mentioned in 72% of the records. No non-empirical records discussed regulation of contents in tobacco products (article 9), economically sufficient alternatives for tobacco workers (article 17), or research, surveillance, and information exchange (article 20). The detailed record of the interventions extracted from non-empirical sources is presented in Table 4.

The focus of empirical and non-empirical literature

Tables 3 and 4 illustrated above show that some of the FCTC articles are taken into consideration by official anti-smoking organizations in SAR, while empirical inquiries taking place in universities and healthcare organizations have been focused on selective articles/strategies of the FCTC. Such discrepancy is summarized in Table 5.

The analysis of data has also identified several articles of FCTC that are not focused or minimally focused on by anti-smoking organizations nor by researchers. The almost neglected articles of FCTC in SAR are presented in Table 6.

Finally, the FCTC article uniformly focused on empirical as well non-empirical data sources was to be article 8 i.e. tobacco smoke protection.

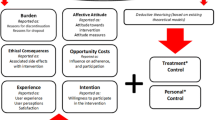

Factors associated with smoking cessation interventions

The 48 included records were reviewed and factors associated with SmC interventions were manually identified through content analysis. Details of codes with frequencies, categories, and themes are provided in supplementary material-II. Factors associated with SmC interventions were divided into barriers and facilitators as discussed herein.

Barriers associated with smoking cessation

Barriers were condensed into four themes (Table 7). At the individual level, the most prevalent SmC barrier found in literature from SAR is lack of awareness regarding the harms associated with cigarette smoking. Furthermore, lack of primary resources to facilitate SmC, lack of interest and motivation, conditioning of smoking with certain situations, and hesitation in seeking support to quit are important barriers to SmC interventions in SAR. At the policy level, ineffective implementation of anti-smoking policy and loopholes in these policies reduce the effectiveness of anti-smoking initiatives in SAR. In some countries, there is no restriction on the sale of single-stick cigarettes [29, 30]. Meanwhile, the measures and tactics used by the tobacco industry are also accelerating tobacco use. Despite bans on cigarette smoking in public spaces, there are still widespread exceptions to this guideline as people smoke in non-air-conditioned coffee shops, restaurants, hotels, airports, and many other public spaces in SAR. At the healthcare level, poor accessibility, lack of resources, role ambiguities as well as lack of interest among healthcare professionals (HCPs) regarding SmC are also commonly observed barriers in SAR. Moreover, social acceptance, motivation, or pressure acquired from social gatherings or parental smoking have also been commonly observed barriers in SAR.

Facilitators associated with smoking cessation

The SmC facilitators were synthesized in four themes (see Table 8). At an individual level, awareness of smoking-associated harms is found as the most prevalent facilitator to SmC interventions and this is further enhanced with the occurrence of any of the smoking-related health risks like a respiratory or cardiovascular issue. In addition, the role of mass media in increasing awareness regarding tobacco hazards is also acknowledged in literature from SAR. In addition, the guilt of harming others through second-hand smoke and the realization of being a source of imitation for non-smokers also increases the smokers’ intention for cessation. Furthermore, readiness for SmC and planning for coping with withdrawal symptoms are also important facilitators for SmC. At the policy level, effective implementation of policies especially related to increased taxation, smoke-free spaces, health warnings, and graphics are important for reducing the prevalence of cigarette smoking in SAR. In Bhutan, the sale of tobacco products is prohibited in the market [42]; however, in Pakistan, due to poor control of the prevalence of cigarette smoking, there are strict recommendations for implementation of MPOWER strategy and strict implementation of anti-smoking laws [37]. At the healthcare level, the establishment of an anti-smoking facilitation center, availability of SmC trained HCPs, and provision of anti-smoking services in outreached communities are important facilitators of SmC interventions in SAR. In Sri Lanka, community-level SmC strategies are complementary to clinical-level supports for reducing the current prevalence of cigarette smoking [34]. At the sociocultural level in SAR, availability of support systems, like family and friends, discussion related to smoking harms in communities, and consideration of sociocultural values while devising anti-smoking policies are imperative to control smoking prevalence.

Discussion

The analysis of data from SAR highlighted important interventions for controlling and/or reducing cigarette smoking. However, the findings suggest that the implementation of FCTC strategies/articles in a uniform way is missing in SAR. There are discrepancies between the research inquiries taking place in universities, hospitals, or other such institutions and the measures taken by different official anti-smoking organizations in SAR. Such discordant directions contribute to a lack of coordination between education, clinical, and anti-smoking organizations’ efforts for smoking cessation in SAR. The need for coordination between clinical and public policy levels has been highlighted in previous literature from south Asian countries [64, 65]. Similarly, a secondary analysis of existing data has shown different countries in South Asia as focusing more on the implementation of specific anti-tobacco policies while lagging in the implementation of others [66].

On the other hand, some of the FCTC articles (refer to Table 6) have been minimally are completely missed in the anti-tobacco efforts in SAR. This delineates the lack of following the Sustainable Development Goal 3A (SDG-3A): which reinforces the implementation of FCTC articles globally [65]. As South Asian countries are the second-highest tobacco products suppliers in the world [66], a priority focus on articles 15 and 17 is immensely important in SAR. However, this review found that these two FCTC articles are not addressed in any of the included empirical studies in this review.

The association between FCTC articles’ implementation and reduced prevalence of tobacco consumption is already reported in literature [66]. However, the current review found only two FCTC articles (8 & 12) addressed in both empirical and non-empirical records at a satisfactory level. Hence, the current review identifies a limited range of anti-smoking initiatives in SAR which is the reason for the majority (84%) of the world’s smokers residing in developing countries and is predicted to grow to 88% in 2025 [66].

Most barriers and facilitators identified in this review aligned with different studies conducted in South and Southeast Asian countries [67,68,69]. However, HCPs’ lack of interest in anti-smoking activities and confusion regarding their roles and responsibilities in SmC surfaced in the current review. Similarly, gradual increase in reluctance to cigarette smoking and second-hand smoke in community people, and availability of any support system for SmC are imperative factors for reducing smoking prevalence in SAR are also unique findings of the current review. Moreover, the scoping review reveals that despite the realization by governmental and non-governmental organizations of the effectiveness of well-implemented anti-smoking laws, the non-committal attitudes of individuals and some officials compromise the successful implementation of the laws.

The current study signifies the need for strong national-level coordination among anti-tobacco organizations, policymakers, researchers, and educators. Also, there is a need for an updated surveillance system for tobacco prevalence, and tobacco cessation and reduction rates. Moreover, the study highlights the need for mobilization of existing resources for the establishment of smoking cessation cells/departments in different localities. Being healthcare professionals, we consider the initiation of such efforts from the tertiary care hospitals’ level. Such anti-smoking cells/departments must not focused only on assisting smokers in quitting, they should also provide training to healthcare professionals for counseling and facilitating smokers in smoking cessation. Lastly, being signatories to FCTC, the south Asian countries must analyze their performance regarding effective or ineffective implementation of the articles presented by the FCTC.

Conclusion

The growing prevalence of cigarette smoking in developing countries has been accentuated as it causes multiple physical and economic harms. The need for context-based interventions with consideration of local barriers and facilitators is made apparent. Implementation of FCTC articles and continuous monitoring can certainly address the situation. The current review provides a significant contribution to the extant SmC efforts made in SAR.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files) and is available publically.

Abbreviations

- BMJ-Open:

-

British Medical Journal Open

- CADHT:

-

Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health

- FCTC:

-

Framework Convention on Tobacco Control

- HCPs:

-

Healthcare professionals

- JBI:

-

Joanna Briggs Institute

- LMICs:

-

Low- and middle-income countries

- MPOWER:

-

M: monitor tobacco use and prevention policies; P: protect people from tobacco smoke; O: offer help to quit tobacco smoking; W: warn about the dangers of tobacco; E: enforce bans on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship; and R: raise taxes on tobacco

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- SAR:

-

South Asian Region

- SmC:

-

Smoking cessation

- SDG-3A:

-

Sustainable Development Goal 3A

- USA:

-

United States of America

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Islami F, Stoklosa M, Drope J, Jemal A. Global and regional patterns of tobacco smoking and tobacco control policies. Eur Urol Focus. 2015;1(1):3–16.

Asma S, Song Y, Cohen J, Eriksen M, Pechacek T, Cohen N, et al. CDC grand rounds: global tobacco control. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(13):277.

World Health Organization. WHO updated fact sheet on Tobacco. 2021. Available from: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco.

WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic. The MPOWER package. 2008. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43818.

Rafique I, Nadeem Saqib M, Bashir F, Naz S, Naz S. Comparison of tobacco consumption among adults in SAARC countries (Pakistan, India and Bangladesh). J Pak Med Assoc. 2018;68(5):S2–6.

Veeranki SP, Mamudu HM, Zheng S, John RM, Cao Y, Kioko D, et al. Secondhand smoke exposure among never-smoking youth in 168 countries. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56(2):167–73.

Wang R, Jiang Y, Yao C, Zhu M, Zhao Q, Huang L, et al. Prevalence of tobacco related chronic diseases and its role in smoking cessation among smokers in a rural area of Shanghai, China: a cross sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1–10.

Martins RS, Junaid MU, Khan MS, Aziz N, Fazal ZZ, Umoodi M, et al. Factors motivating smoking cessation: a cross-sectional study in a lower-middle-income country. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–11.

World Health Organization. WHO framework convention on tobacco control. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. ISBN 978 92 4 159101 0.

World Health Organization. The WHO framework convention on tobacco control: 10 years of implementation in the African region: World Health Organization; 2015. ISBN: 978 9290232773. WHO Regional Office for Africa

Chung-Hall J, Craig L, Gravely S, Sansone N, Fong GT. Impact of the WHO FCTC over the first decade: a global evidence review prepared for the impact assessment expert group. Tob Control. 2019;28(Suppl 2):s119–s28.

Gravely S, Giovino GA, Craig L, Commar A, D’Espaignet ET, Schotte K, et al. Implementation of key demand-reduction measures of the WHO framework convention on tobacco control and change in smoking prevalence in 126 countries: an association study. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2(4):e166–e74.

Bilano V, Gilmour S, Moffiet T, d'Espaignet ET, Stevens GA, Commar A, et al. Global trends and projections for tobacco use, 1990–2025: an analysis of smoking indicators from the WHO Comprehensive information Systems for Tobacco Control. Lancet. 2015;385(9972):966–76.

Jamal A, Phillips E, Gentzke AS, Homa DM, Babb SD, King BA, et al. Current cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2016. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(2):53.

Grills NJ, Singh R, Singh R, Martin BC. Tobacco usage in Uttarakhand: a dangerous combination of high prevalence, widespread ignorance, and resistance to quitting. BioMed Res Int. 2015;2015(Article ID 132120):10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/132120.

Gadhave SA, Nagarkar A. Tobacco control interventions during last decade in India: a narrative review. Natl J Community Med. 2017;8(12):743–51.

McKay AJ, Patel RK, Majeed A. Strategies for tobacco control in India: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0122610.

Heckman CJ, Egleston BL, Hofmann MT. Efficacy of motivational interviewing for smoking cessation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tob Control. 2010;19(5):410–6.

Lemmens V, Oenema A, Knut IK, Brug J. Effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions among adults: a systematic review of reviews. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2008;17(6):535–44.

Riemsma RP, Pattenden J, Bridle C, Sowden AJ, Mather L, Watt IS, et al. Systematic review of the effectiveness of stage based interventions to promote smoking cessation. BMJ. 2003;326(7400):1175–7.

Barroso-Hurtado M, Suárez-Castro D, Martínez-Vispo C, Becoña E, López-Durán A. Smoking cessation apps: a systematic review of format, outcomes, and features. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(21):11664.

Shahab L, McEwen A. Online support for smoking cessation: a systematic review of the literature. Addiction. 2009;104(11):1792–804.

Bottorff JL, Haines-Saah R, Kelly MT, Oliffe JL, Torchalla I, Poole N, et al. Gender, smoking and tobacco reduction and cessation: a scoping review. Int J Equity Health. 2014;13(1):1–15.

Dono J, Miller C, Ettridge K, Wilson C. The role of social norms in the relationship between anti-smoking advertising campaigns and smoking cessation: a scoping review. Health Educ Res. 2020;35(3):179–94.

Puleo GE, Borger T, Bowling WR, Burris JL. The state of the science on Cancer diagnosis as a “teachable moment” for smoking cessation: a scoping review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2021;24(2):160–8.

Iqbal S, Barolia R, Ladak L, Petrucka P. Smoking cessation interventions in south Asian countries: protocol for scoping review. BMJ Open. 2021;11(2):e038818.

Peters MD, Marnie C, Tricco AC, Pollock D, Munn Z, Alexander L, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18(10):2119–26.

Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

WHO-FCTC. RTI International, Ministry of Health, Sri Lanka United Nations Development Programme. The case for investing in WHO FCTC implementation in Sri Lanka. 2019. Available from: https://www.undp.org/publications/investment-case-tobacco-control-sri-lanka.

Tobacco Control Laws. Lagislation by country: Bangladesh; 2021. Available from: https://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/legislation/country/Bangladesh/summary.

Bhaumik SS, Placek C, Kochumoni R, Lekha T, Prabhakaran D, Hitsman B, et al. Tobacco cessation among acute coronary syndrome patients in Kerala, India: patient and provider perspectives. Qual Health Res. 2019;29(8):1145–60.

Razzaq S, Kazmi T, Athar U, editors. Prevalence of tobacco use and its determinants among adults aged 18 years and above in urban slum of Lahore, Pakistan: WHO STEPS survey. ISEE Conference Abstracts. 2020.

Suhaj A, Manu MK, Unnikrishnan M, Vijayanarayana K, Mallikarjuna RC. Effectiveness of clinical pharmacist intervention on health-related quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder patients–a randomized controlled study. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2016;41(1):78–83.

Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka. Smoking cessation Policies in Sri Lanka. 2020. Available from: https://www.ips.lk/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Smoking-Cessation_final.pdf.

Anil OM, Yadav RS, Shrestha N, Koirala S, Shrestha S, Nikhil OM, et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in apparently healthy urban adult population of Kathmandu. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2019;16(41):438–45.

Foundation for a Smoke Free World. State of smoking in India. 2019. Available from: https://www.smokefreeworld.org/health-science-technology/health-science-technology-agenda/data-analytics/global-state-of-smoking-landscape/state-smoking-india/.

World Health Organization. Tobacco free initiative: Pakistan; 2021. Available from: http://www.emro.who.int/pak/programmes/tobacco-free-initiative.html.

Elsey H, Dogar O, Ahluwalia J, Siddiqi K. Predictors of cessation in smokers suspected of TB: secondary analysis of data from a cluster randomized controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;155:128–33.

Cell TC. Ministry of National Health Services, Regulations and Coordinations, Pakistan. 2017. Available from: http://www.tcc.gov.pk/index.php.

Agarwal A, Jindal D, Ajay VS, Kondal D, Mandal S, Ghosh S, et al. Association between socioeconomic position and cardiovascular disease risk factors in rural North India: the Solan surveillance study. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0217834.

Tobacco Control Laws. Lagislation by country: Pakistan; 2020. Available from: https://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/legislation/country/pakistan/summary.

Tobacco Control Laws. Lagislation by country: Bhutan. 2020. Available from: https://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/legislation/country/Bhutan/summary.

Tobacco Control Laws. Lagislation by country: Afghanistan. 2019. Available from: https://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/legislation/country/Afghanistan/summary.

The Union. Tobacco control in India: the tobacco epidemic. 2020.

Raspanti GA. Lung cancer in Nepal: the role of traditional tobacco products and combustion related household air pollution; 2016.

Siddiqi K, Siddiqui F, Khan A, Ansaari S, Kanaan M, Khokhar M, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on smoking patterns in Pakistan: findings from a longitudinal survey of smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2021;23(4):765–9.

Irfan M, Haque A, Shahzad H, Samani Z, Awan S, Khan J. Reasons for failure to quit: a cross-sectional survey of tobacco use in major cities in Pakistan. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2016;20(5):673–8.

Nichter M, Padmajam S, Nichter M, Sairu P, Aswathy S, Mini G, et al. Developing a smoke free homes initiative in Kerala, India. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1–9.

Sah R, Pradhan B, Subedi L, Karki P, Jha N. Epidemiological study of tobacco smoking behaviour amongst residents of the hill region of Nepal. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2016;14(55):215–20.

Navya N, Jeyashree K, Madhukeshwar AK, Anand T, Nirgude AS, Nayarmoole BM, et al. Are they there yet? Linkage of patients with tuberculosis to services for tobacco cessation and alcohol abuse–a mixed methods study from Karnataka, India. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):1–12.

Elsey H, Khanal S, Manandhar S, Sah D, Baral SC, Siddiqi K, et al. Understanding implementation and feasibility of tobacco cessation in routine primary care in Nepal: a mixed methods study. Implement Sci. 2015;11(1):1–12.

The Tobacco Altas: Bangladesh. American Cancer Society, Inc. and Vital Strategies. 2021. Available from: https://tobaccoatlas.org/country/Bangladesh/. Accessed 30 June 2021.

The Union: Pakistan. Tobacco control in Pakistan: the tobacco epidemic. 2020. Available from: https://theunion.org/our-work/tobacco-control/bloomberg-initiative-to-reduce-tobacco-use-grants-program/tobacco-control-in-pakistan.

Prasad JB, Dhar M. A descriptive method of combining multiple outcomes of multiple exposures with application to cancer patients. Child Health Mortal. 2019;145. Shyam Institute, India. ISBN: 978-92-82411-15-4.

Dogar O, Barua D, Boeckmann M, Elsey H, Fatima R, Gabe R, et al. The safety, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of cytisine in achieving six-month continuous smoking abstinence in tuberculosis patients—protocol for a double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial. Addiction. 2018;113(9):1716–26.

Karmacharya B, Fitzpatrick A, Koju R, Sotodehnia N, Xu D, Pradhan P, et al. Quit intentions and attempts among smokers in sub-urban Nepal: findings from the Dhulikhel heart study. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2018;61(1):83–8.

The Tobacco Altas: Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka: American Cancer Society, Inc. and Vital Strategies. 2021. Available from: https://tobaccoatlas.org/country/sri-lanka/. Accessed 30 June 2021.

Ali RAB, Harraqui K, Hannoun Z, Monir M, Samir M, Anssoufouddine M, et al. Nutrition transition, prevalence of double burden of malnutrition and cardiovascular risk factors in the adult population living in the island of Anjouan, Comoros. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;35:89.

Tobacco Control Laws. Lagislatoin by country: India. 2020. Available from: https://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/legislation/country/india/summary.

Kanakia KP, Majella MG, Thekkur P, Ramaswamy G, Nair D, Chinnakali P. High tobacco use among presumptive tuberculosis patients, South India: time to integrate control of two epidemics. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2016;7(4):228–32.

National Health Portal: India. mCessation Programme (quit tobacco for life) 2016. Available from: https://www.nhp.gov.in/quit-tobacco.

Kumar S, Pooranagangadevi N, Rajendran M, Mayer K, Flanigan T, Niaura R, et al. Physician’s advice on quitting smoking in HIV and TB patients in South India: a randomised clinical trial. Public Health Action. 2017;7(1):39–45.

Gamlath L, Nandasena S, de Silva P, Morrell S, Linhart C, Lin S, et al. Community intervention for cardiovascular disease risk factors in Kalutara, Sri Lanka. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2020;20(1):1–17.

Hameed A, Malik D. Barriers to cigarette smoking cessation in Pakistan: evidence from qualitative analysis. J Smok Cessat. 2021;2021(Article ID 9592693):9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/9592693.

World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2017: monitoring tobacco use and prevention policies Switzerland. 2017. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/255874/9789241512824-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Shahzad M, Shah A, Chaloupka FJ. Tobacco control Laws of south Asian countries: a quantitative-comparative analysis of compliance with FCTC and their effects on smoking prevalence. Bus Econ Rev. 2020;12(4):97–130.

Warsi S, Elsey H, Boeckmann M, Noor M, Khan A, Barua D, et al. Using behaviour change theory to train health workers on tobacco cessation support for tuberculosis patients: a mixed-methods study in Bangladesh, Nepal and Pakistan. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):1–14.

Yang T, Abdullah ASM, Mustafa J, Chen B, Feng X. Factors associated with smoking cessation among Chinese adults in rural China. Am J Health Behav. 2009;33(2):125–34.

Abdullah AS, Driezen P, Quah AC, Nargis N, Fong GT. Predictors of smoking cessation behavior among Bangladeshi adults: findings from ITC Bangladesh survey. Tob Induc Dis. 2015;13(1):1–10.

Acknowledgments

We thank Head Librarian (information specialist) Mr. Khawaja Mustafa, Aga Khan University Karachi, Pakistan, for his consistent guidance and support in managing the search as well as the Endnote software record of this scoping review.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sajid Iqbal: Coordinated with all the team members. Conducted meeting with the librarian and actively involved in the formulation of search syntax, literature search and reviewed the retrieved data for inclusion and exclusion. He, with the help of the remaining authors, analyzed the data and presented the results. He wrote the manuscript for publication and acquire feedback from the rest of the authors. Dr. Pammla Petrucka: She participated in every step of the review and provided critical feedback. She provided critical feedback on the write-up and helped in composing the whole review process. Dr. Laila Ladak: She provided critical feedback and gave appropriate directions for the successful execution of the review process. Abdul Kabir: Actively worked on data extraction from searched sources. Participated in the process of reviewing the extracted literature. Rameesha Rehmani: Actively assisted in data extraction, management, and revision of included and excluded articles for any need of re-consideration. Dr. Rubina Barolia: Conceived the basic idea and supervised the whole review process. Provided directions in using the selected framework and facilitated the process of analysis. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable as the review did not involve human or animal study subjects.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Material-I.

Characteristics of retrieved studies. Supplementary Material II. Factors associated with smoking cessation interventions. Supplementary Material-III. PubMed. CINAHL. Wiley Cochrane. ProQuest Thesis.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Iqbal, S., Barolia, R., Petrucka, P. et al. Smoking cessation interventions in South Asian Region: a systematic scoping review. BMC Public Health 22, 1096 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13443-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13443-y