Abstract

Background

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is one of the major public health challenges generating a relevant burden. High-risk groups, including people who inject drugs (PWID), are at serious risk for developing HCV. In recent years, several investigations have been conducted in Iran to assess the prevalence e of HCV among PWID. The aim of the present study was to synthesize the literature performing a comprehensive search and meta-analysis.

Methods

A comprehensive literature search was carried out from January 2000 to September 2019. Several international databases, namely Scopus, PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, ISI/Web of Science, PsycINFO, CINAHL, the Cochrane Library and the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ), as well as Iranian databases (Barakathns, SID and MagIran), were consulted. Eligible studies were identified according to the following PECOS (population, exposure, comparison/comparator, outcome and study type) criteria: i) population: Iranian population; ii) exposure: injection drug users; iii) comparison/comparator: type of substance injected and level of substance use, iv) outcome: HCV prevalence; and v) study type: cross-sectional study. After finding potentially related studies, authors extracted relevant data and information based on an ad hoc Excel spreadsheet. Extracted data included the surname of the first author, the study journal, the year of publication, the number of participants examined, the type of diagnostic test performed, the number of positive HCV patients, the number of participants stratified by gender, the reported prevalence, the duration of drug injection practice and the history of using a shared syringe.

Results

Forty-two studies were included. 15,072 PWID were assessed for determining the prevalence of HCV. The overall prevalence of HCV among PWID in Iran was computed to be 47% (CI 95: 39–56). The prevalence ranged between 7 and 96%. Men and subjects using a common/shared syringe were 1.46 and 3.95 times more likely to be at risk, respectively.

Conclusion

The findings of the present study showed that the prevalence of HCV among PWIDs in Iran is high. The support and implementation of ad hoc health-related policies and programs that reduce this should be put into action.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Health policy- and decision-makers consider hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection as one of the major health challenges in the field of public health, in that it generates a relevant burden, both in epidemiological and clinical terms [1]. High-risk groups such as prisoners, people with HIV, those who receive blood products and people who inject drugs (PWID) are at serious risk for HCV [2]. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that in 2015 around 1.75 million new cases of infections occurred worldwide. According to the WHO, the highest prevalence of infection was reported in the Eastern Mediterranean (2.3%), and in the European (1.5%) regions [3].

Among the high-risk groups for HCV, PWID represent a category that needs to be monitored and checked carefully [4]. Unsafe injection is one of the main ways of transmitting HCV infection [5], in particular, the usage of common syringes, which is quite a widespread practice among PWID [6]. The risk of HCV infection among these people is higher than the risk among HIV patients. Identifying high-risk groups can greatly help the healthcare system prevent and control various communicable diseases [7, 8].

Chronic HCV infection can cause cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma and ultimately lead to death [9]. Due to the severe clinical outcomes, the high costs of the treatment and the absence of effective vaccines for HCV, health policy- and decision-makers tend to especially focus on prevention, control and management of HCV patients [10]. The WHO has identified the HCV elimination plan for 2030 as an important, ambitious goal, and as such, one of the most important ways to achieve this goal is to screen and control the disease in high-risk groups such as PWID [11].

The Middle East region is one of the areas worldwide in which HCV is highly prevalent. The risk of the transmission and spreading of HCV among PWID has increased in the last years as a result of the transit of drugs and addicted people through Afghanistan and neighboring countries [12]. Iran is one of the countries in the Eastern Mediterranean region, with about 186,000 HCV patients [13]. According to a recently published systematic review and meta-analysis, the prevalence of HCV in Iran is about 0.6% [14]. Despite the fact that this rate is lower compared to many neighboring countries in the area, the rate among high-risk groups such as PWID has considerably increased and this is a serious warning for Iranian health policy- and decision-makers [15]. Neighborhood with countries like Afghanistan is one of the major causes of this increase, and the Iranian government has been trying to mobilize all its resources to cope with this challenge [13].

In recent years, several investigations have been conducted in Iran to assess the prevalence of HCV among PWID, in order to provide planners with good evidence that can be used to implement appropriate health-related policies [16]. Like other countries in the world, also in Iran people who use personal or common syringes for intravenous injections are defined as PWID [17].

Understanding the epidemiologic status can provide a clearer and more appropriate framework for decision-and policy-makers in the health sector. They can use this information to develop their programs and plans in the different areas of HCV control and management. Health policy-and decision-makers, using available evidence, can effectively curb the costs generated by HCV in their country.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the prevalence of HCV among PWID by performing a comprehensive literature search and meta-analysis of published studies and to critically evaluate and appraise the policies that the health sector has been trying to implement in order to reduce the burden of HCV in Iran.

Methods

Systematic review and meta-analysis study protocol

The study protocol has been prospectively registered within the PROSPERO database (identification ID: CRD42019122601) [18] and the main findings are here reported in accordance with the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses” (PRISMA) guidelines [19].

Search strategy

A comprehensive literature search has been carried out in order to retrieve relevant studies related to the topic under study, from January 2000 to September 2019. Several international databases, repositories and bibliographic thesauri, namely Scopus, PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, ISI/Web of Science, PsycINFO, CINAHL, the Cochrane Library and the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ), as well as Iranian databases (Barakathns, SID and MagIran), have been mined independently by two researchers. To minimize the chance of not capturing all relevant studies and to find more potentially related studies, also the gray literature was consulted via Google Scholar. Furthermore, references lists of each potentially eligible study were evaluated and hand-searched.

The following search strategy was used: (prevalence OR seroprevalence OR frequency OR rate OR epidemiology) AND (“hepatitis C virus” OR “hepatitis C infection” OR “HCV” OR “viral hepatitis” OR hepatitis OR “hepatitis C antibodies”) AND (“injection drug users” OR “IDUs” OR “injection substance users” OR “injection drug use” OR “injection substance use” OR “intravenous drug users” OR “intravenous substance users” OR “drug users” OR “substance users” OR “drug injection” OR “substance injection” OR “drug addicts” OR “substance addicts” OR “injection drugs” OR “injection substances” OR “injecting drug” OR “injecting substance” OR “substance injection” OR “drug injection” OR “substance-injecting practice” OR “drug-injecting practice” OR “inject substance” OR “inject drug” OR “inject substance” OR “injecting drug users” OR “injecting substance users” OR “drug injection history” OR “substance injection history” OR “injection drug abusers” OR “injection substance abusers” OR “drug abusers” OR “substance abusers” OR “intravenous drug abuse” OR “intravenous substance abuse” OR “IV drug users” OR “IV substance users” OR “illicit drug injection” OR “illicit substance injection” OR “people who inject drugs” OR PWID OR “people who inject substances”) AND Iran. Differences in selected studies between two authors were resolved by consensus.

Eligibility criteria

Eligible studies were identified according to the following PECOS (population, exposure, comparison/comparator, outcome and study type) criteria: i) population: Iranian population; ii) exposure: injection drug users; iii) comparison/comparator: type of substance injected and level of substance use, iv) outcome: HCV prevalence; and v) study type: cross-sectional study.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows: i) studies were considered eligible if published in Persian or English; ii) published in peer-reviewed journals; iii) reporting HCV prevalence or with sufficient data, providing the possibility to calculate HCV prevalence among PWID; iii) using standardized tests to detect HCV, namely recombinant immunoblot assay (RIBA), polymerase-chain reaction (PCR) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA); iv) devised as observational studies (of any kind: cross-sectional, cohort, or case-control); v) conducted in Iran; and vi) carried out without any limitations in terms of age and gender.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria were as follows: i) studies were not deemed eligible if devised as case reports, case-series, reviews or systematic reviews (even though, if available, reference lists of reviews were scanned for ensuring a comprehensive coverage of the literature); ii) published as conferences abstracts or in proceedings; iii) not reporting HCV prevalence or not providing clear, suitable data for estimating HCV prevalence; iv) conducted among HIV-positive individuals or subjects with other disorders; v) not carried out in Iran; and vi) with overlapping/duplicate data.

Screening and data extraction

After finding potentially related studies, authors extracted relevant data and information based on ad hoc Excel spreadsheet. Extracted data included the surname of the first author, the study journal, the year of publication, the number of participants examined, the type of diagnostic test performed, the number of positive HCV patients, the number of participants stratified by gender, the reported prevalence, the duration of drug injection practice and the history of using a shared syringe.

Study quality appraisal

The Joanna Brigg’s Institute (JBI) checklist was used to check the quality of selected studies [20]. This checklist has 10 questions and is particularly suitable for the appraisal of epidemiological and prevalence studies. The answer to each question is yes, no, unclear or not applicable.

Statistical analysis

For all data analysis, the commercial software STATA Ver.14 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA) was used. Figures with p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. To calculate HCV prevalence among Iranian PWID, a random-effect model according to the DerSimonian-Laird approach with the Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation with 95% confidence interval (CI) was used [21, 22]. For computing the amount of heterogeneity among studies, the I2 statistics was utilized [23]. The Egger’s linear regression test was used for assessing the presence of publication bias [24]. Based on the age of the participants, sample size, duration of injection (based on the selected studies, the mean duration of injection was calculated by the authors to be 3 years) and geographic region of the study, subgroup analyses were carried out. Furthermore, sensitivity analysis was performed in order to ensure the stability of the results. Also, to further investigate the possible sources of heterogeneity among studies, meta-regressions were conducted based on the year of study, sample size and age of participants.

Results

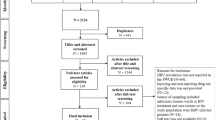

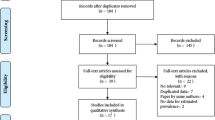

The initial search of the literature yielded a pool of 474 records. Figure 1 shows the process of searching, retrieving and selecting relevant studies. 68 records were duplicate items and, as such, were removed. The title of the studies was then reviewed and at that step 321 records were removed. The abstract of the articles was reviewed and, finally, 42 studies were retained based on the above-mentioned inclusion and exclusion criteria [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66].

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the 42 studies included in the present study (all 42 investigations were designed as cross-sectional studies). 15,072 PWID were assessed for determining the prevalence of HCV. Retained studies were published between 2001 and 2017. Mean age was ranging between 20 and 42 years. All studies used ELISA to detect HCV.

The critical methodological assessment of the quality of selected studies is presented in Table 2, showing the high methodological rigor of the included investigations.

According to the DerSimonian-Laird random-effect model, the overall prevalence of HCV among PWID in Iran was computed to be 47% (CI 95: 39–56). The prevalence ranged between 7 and 96%. The I2 statistics yielded a value of 99.4%, indicating high, statistically significant heterogeneity among studies. Figure 2 shows the forest plot of the selected studies.

Several subgroup-analyzes were conducted to explore the sources of heterogeneity among studies. Table 3 shows the results based on sample size, imprisoned PWID, geographic regions, age, and duration of injection.

The sensitivity analysis was performed and based on it the results before and after removing each study per time did not change, showing that the results were stable and reliable.

Based on sample size, year of publication and mean age of participants, meta-regression analyses were conducted. The findings showed that the prevalence tended to decrease by sample size (P = 0.063) and year of publication (P = 0.039), both statistically significant. Similarly, as the age increased, the prevalence declined in a statistically significant fashion (P = 0.061). Figure 3 shows the results of the meta-regressions.

Six studies provided data that enabled to estimate the odds ratio (OR) of HCV infection in terms of gender. The OR for HCV among PWID men was about 1.46 times that of women, statistically significant and suggesting that men were at higher risk of developing HCV compared to women (Fig. 4).

Some studies assessed the impact of using a common/shared syringe showing that individuals who used a common syringe for injection were 3.95 times more likely to be at risk. Figure 5 shows the odds ratio for using a common syringe.

Publication bias was evaluated by performing the Egger’s linear regression test and we could not find any evidence of publication bias in included studies according to P = 0.23 (Fig. 6).

Discussion

Planning to implement appropriate and effective programs to prevent and control diseases requires the use of robust and updated scientific evidence. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of HCV among the PWID, a well-known high-risk group for developing HCV. The findings of this study showed that the prevalence was 47%. This was higher than the prevalence of HCV among prisoners (28%) [67], thalassemia patients (19%) [68], street children (2.4%) [69], blood donors (0.5%) [70] and the general population (0.6%) [14]. This high rate confirms that, as it is well-known, PWID are one of the most important and high-risk groups for developing HCV [2, 71].

The prevalence of HCV among PWID in Iran was lower than the rate reported in other countries, including South Africa (55%) [72], Pakistan (72%) [73] and India (53.7%) [74] but higher than in studies conducted in Kuwait (12.28%) [4], Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (42.7%) [75], and Brazil (35.6%) [76]. These differences in prevalence can be attributed to differences in health systems, screening methods, and the type of high-risk behaviors of individuals [77, 78]. In particular, in developing countries, harm reduction programs such as syringe distribution are not fully implemented [79]. Furthermore, because of the high cost of diagnostic services, many PWID are not aware of their health status. The high cost of management and the lack of referral for treatment can also be some of the reasons explaining the contrasting findings among various studies [80, 81].

The findings of this study showed that the highest prevalence of HCV among PWID in Iran was observed in East and South of Iran (60%). Neighborhood of countries such as Afghanistan and Pakistan could explain, at least partially, such findings [82]. Moreover, there are a lot of harbors in Southern Iran, which is one of the ways to transport narcotic drugs to other countries. For this reason, addicts in the area from Iran have easy access conditions. One of the most important policies implemented by the government in Iran is a serious struggle against the narcotics commerce and sale, with the support of international organizations [83].

Moreover, the findings of this study showed that the prevalence of HCV in men was higher than that among women, which was consistent with the results of studies performed in India [84] as well as in upper middle-income countries [78]. Men were found to be more likely to be at risk than women, probably due to differences in lifestyles and behaviors that make men more susceptible to HCV. The cultural and social conditions in Iran have led men to become more oriented toward injecting drug use than women. As such, most of the participants evaluated in the studies included in the present systematic review and meta-analysis were male.

The findings showed that the prevalence of infections in people who had a history less than 3 years of injection was higher than the rate among those who had an injection history longer than 3 years. A reason could be the early detection of the disease in these people. Unfortunately, one of the problems with HCV is that many people are not aware of their illness, not having access to diagnostic services, due to the expensive testing costs, and the lack of motivation to diagnose possible illnesses [27, 52, 58, 65].

PWID that had a history of sharing needles had a 3.95-fold increased risk of developing HCV infection, which is in line with the literature [4, 85]. Various studies have shown that needle exchange programs (NEP) can be used as a harm reduction policy to decrease HCV prevalence among PWID, even though the effectiveness of this program has yet to be properly verified [86, 87].

Meta-regressions showed that the prevalence of HCV among PWID in Iran has decreased in recent years, even though not in a statistically significant way. This decrease reflects the widespread effort to reduce HCV-related risk of diffusion and transmission. Health policy- and decision-makers in Iran have adopted valuable harm reduction policies to prevent and control HCV among high-risk groups, and especially PWID. The Ministry of Health, as the most important actor in controlling the disease, has been developing educational programs for the general population, as well as for the high-risk groups. Establishing centers in all provinces for the distribution of syringes, condoms and alternative treatments such as methadone has enabled to obtain good results. In these centers, diagnostic tests are performed free of charge for PWID and others who have high-risk behaviors. The support of the judiciary system in Iran has led to a serious emphasis on screening programs in Iranian prisons. There are also special centers for women who offer harm reduction services. All these activities have contributed to controlling the disease.

The findings of the present study showed that the prevalence of HCV was higher in studies involving only prisoners (52%) compared to studies involving non-prisoners (45%). Prison for individuals can be an important risk factor for injecting drug use (IDU) [88]. The absence or inappropriate implementation of risk reduction policies in prisons around the world has led to serious problems for prisoners [89]. The pattern of drug use in Iran has changed in recent decades and IDUs are on the rise [67]. In one sense, prisoners practicing IDU are more susceptible to infections such as HBV, HCV and HIV than others [90].

However, this study has some limitations, which should be properly acknowledged. Epidemiological studies of HCV prevalence among PWID were not performed in all provinces and areas of Iran. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct observational surveys in all provinces in order to obtain a clear understanding of the disease condition. High amounts of heterogeneity as shown by the I2 statistics indicate that there are methodological differences among studies, as indicated also by the subgroup analysis. Other limitations include the lack of sufficient quantitative data from some studies that hindered the possibility of computing HCV prevalence, especially stratifying by age-groups and gender.

Conclusion

The findings of the present study showed that the prevalence of HCV among PWIDs in Iran is high. The support and implementation of ad hoc health-related policies and programs that reduce this should be put into action. Alternative treatments such as methadone therapy and HCV therapy can help control the problem. Health policy- and decision-makers in Iran should provide faster diagnosis and access to low-cost health care.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- DOAJ:

-

Directory of Open Access Journals

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- HCV:

-

Hepatitis C virus

- IDU:

-

Injecting drug use

- JBI:

-

Joanna Brigg’s Institute

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PCR:

-

Polymerase-chain reaction

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- PWID:

-

People who inject drugs

- RIBA:

-

Recombinant immunoblot assay

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Platt L, Easterbrook P, Gower E, McDonald B, Sabin K, McGowan C, et al. Prevalence and burden of HCV co-infection in people living with HIV: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:797–808.

Nelson P, Mathers B, Cowie B, Hagan H, Jarlais DD, Horyniak D, et al. The epidemiology of viral hepatitis among people who inject drugs: results of global systematic reviews. Lancet. 2011;378(9791):571–83.

World Health Organization. Hepatitis C 2019 [Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-c.

Altawalah H, Essa S, Ezzikouri S, Al-Nakib W. Hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus and human immunodeficiency virus infections among people who inject drugs in Kuwait: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):6292.

Davis SM, Kristjansson AL, Davidov D, Zullig K, Baus A, Fisher M. Barriers to using new needles encountered by rural Appalachian people who inject drugs: implications for needle exchange. Harm Reduct J. 2019;16(1):23.

Gicquelais RE, Foxman B, Coyle J, Eisenberg MC. Hepatitis C transmission in young people who inject drugs: Insights using a dynamic model informed by state public health surveillance. Epidemics. 2019;S1755–4365(18):30103–8.

Echevarria D, Gutfraind A, Boodram B, Layden J, Ozik J, Page K, et al. Modeling indicates efficient vaccine-based interventions for the elimination of hepatitis C virus among persons who inject drugs in metropolitan Chicago. Vaccine. 2019;37(19):2608–16.

Richardson D, Bell C. Public health interventions for reducing HIV, hepatitis B and hepatitis C infections in people who inject drugs. Public Health Action. 2018;8(4):153.

Schulkind J, Stephens B, Ahmad F, Johnston L, Hutchinson S, Thain D, et al. High response and re-infection rates among people who inject drugs treated for hepatitis C in a community needle and syringe programme. J Viral Hepat. 2019;26(5):519–28.

Bouscaillou J, Kikvidze T, Butsashvili M, Labartkava K, Inaridze I, Etienne A, et al. Direct acting antiviral-based treatment of hepatitis C virus infection among people who inject drugs in Georgia: a prospective cohort study. Int J Drug Policy. 2018;62:104–11.

Waheed Y, Siddiq M, Jamil Z, Najmi MH. Hepatitis elimination by 2030: progress and challenges. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24(44):4959–61.

Cousien A, Tran VC, Deuffic-Burban S, Jauffret-Roustide M, Dhersin JS, Yazdanpanah Y. Hepatitis C treatment as prevention of viral transmission and liver-related morbidity in persons who inject drugs. Hepatology. 2016;63(4):1090–101.

Behzadifar M, Gorji HA, Rezapour A, Bragazzi NL. The hepatitis C infection in Iran: a policy analysis of agenda-setting using Kingdon's multiple streams framework. Health Res Policy Syst. 2019;27(1):30.

Mirminachi B, Mohammadi Z, Merat S, Neishabouri A, Sharifi AH, Alavian SH, et al. Update on the prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection among Iranian general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepat Mon. 2017;17(12):e42291.

Behzadifar M, Gorji HA, Rezapour A, Rezvanian A, Bragazzi NL, Vatankhah S. Hepatitis C virus-related policy-making in Iran: a stakeholder and social network analysis. Health Res Policy Syst. 2019;17(1):42.

Shaheen MA, Idrees M. Evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis, prevention and management of hepatitis C virus disease. World J Hepatol. 2015;7(3):616–62.

World Health Organization. People who inject drugs 2019 [Available from: https://www.who.int/hiv/topics/idu/en/. Last access (26 December 2019).

Behzadifar M, Khanizadeh S, Behzadifar M, Bragazzi NL, Malekshahi A, Khaksar MJ, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis C infection in injecting drug users in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. 2019PROSPERO 2019 CRD42019122601 [Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php? ID=CRD42019122601.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700.

Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and incidence data. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):147–53.

DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials revisited. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;45(Pt A):139–45.

Freeman MF, Tukey JW. Transformations related to the angular and the square root. Ann Math Stat. 1950;21(4):607–11.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60.

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–34.

Zali MR, Aghazadeh R, Nowroozi A, Amir-Rasouly H. Anti-HCV antibody among iranian iv drug users: is it a serious problem? Arch Irn Med. 2001;4(3):115–9.

Rowhani Rahbar A, Rooholamini S, Khoshnood K. Prevalence of HIV infection and other blood-borne infections in incarcerated and non-incarcerated injection drug users (IDUs) in Mashhad, Iran. Int J Drug Policy. 2004;15(2):151–5.

Mohammad Alizadeh AH, Alavian SM, Jafari K, Yazdi N. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection and its related risk factors in drug abuser prisoners in Hamedan--Iran. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(26):4085–9.

Sarvghad M, Naderi HR, Farokhnia M, Bojdi A. An epidemiologic study of hospitalized iv drug abusers in infectious diseases ward of immam reza hospital of Mashhad. Med J Mashhad Uni Med Sci. 2005;48(87):79–84.

Imani R, Karimi A, Kassaian N. The relevance of related-risk behaviors and seroprevalence of HBV, HCV and HIV infection in intravenous drug users from Shahrekord, Iran, 2004. J Shahrekord Univ Med Sci. 2006;8(1):58–62.

Aminzadeh Z, Aghazadeh SK. Seroepidemiology of HIV, syphilis, hepatitis B and C in intravenous drug users at Loghman hakim hospital. Iran J Med Microbiol. 2007;1(3):53–6.

Mohtasham Amiri Z, Rezvani M, Jafari Shakib R, Jafari SA. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection and risk factors of drug using prisoners in Guilan province. East Mediterr Health J. 2007;13(2):250–6.

Zamani S, Ichikawa S, Nassirimanesh B, Vazirian M, Ichikawa K, Gouya MM, et al. Prevalence and correlates of hepatitis C virus infection among injecting drug users in Tehran. Int J Drug Policy. 2007;18(5):359–63.

Imani R, Karimi A, Rouzbahani R, Rouzbahani A. Seroprevalence of HBV, HCV and HIV infection among intravenous drug users in Shahr-e-Kord, Islamic Republic of Iran. East Mediterr Health J. 2008;14(5):1136–41.

Mir-Nasseri MM, Poustchi H, Nasseri-Moghadam S, Tavakkoli H, Mohammadkhani A, Afshar P, et al. Hepatitis C seroprevalence among intravenous drug users in Tehran. J Res Med Sci. 2008;13(6):295–302.

Soudbakhsh AR, Nami MA, Hadjiabdolbaghi M, Kazemi B. Transfusion transmitted virus prevalence rate in IDU patients: a cross sectional study. Tehran Univ Med J. 2008;66(4):282–7.

Alavi SM, Alavi L. Seroprevalence study of HCV among hospitalized intravenous drug users in Ahvaz, Iran (2001—2006). Journal of Infection and Public Health. 2009;2(1):47–51.

Davoodian P, Dadvand H, Mahoori K, Amoozandeh AS. Alavati a. prevalence of selected sexually and blood-borne infections in injecting drug abuser inmates of Bandar Abbas and roodan correction facilities, Iran, 2002. Braz J Infect Dis. 2009;13(5):356–8.

Kheirandish P, SeyedAlinaghi S, Jahani M, Shirzad H, Seyed Ahmadian M, Majidi A, et al. Prevalence and correlates of hepatitis C infection among male injection drug users in detention, Tehran. Iran J Urban Health. 2009;86(6):902–8.

Mirahmadizadeh AR, Majdzadeh R, Mohammad K, Forouzanfar M. Prevalence of HIV and hepatitis C virus infections and related behavioral determinants among injecting drug users of drop-in centers in Iran. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2009;11(3):325–9.

Sharif M, Sherif A, Sayyah M. Frequency of HBV, HCV and HIV infections among hospitalized injecting drug users in Kashan. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2009;30(1):28–30.

Tajbakhsh E, Paiedar F. Seroepidemiological study of HCV infections in Shahrekord jail prisoners. J Microbial World. 2009;1(1):23–8.

Alavi SM, Behdad F. Seroprevalence study of hepatitis C and hepatitis B virus among hospitalized intravenous drug users in Ahvaz, Iran (2002-2006). Hepat Mon. 2010;10(2):101–4.

Hosseini M, SeyedAlinaghi S, Kheirandish P, Esmaeli Javid G, Shirzad H, Karami N, et al. Prevalence and correlates of co-infection with human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus in male injection drug users in Iran. Arch Iran Med. 2010;13(4):318–23.

Merat S, Rezvan H, Nouraie M, Jafari E, Abolghasemi H, Radmard AR, et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis C virus: the first population-based study from Iran. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14S:e113–6.

Zamani S, Radfar R, Nematollahi P, Fadaie R, Meshkati M, Mortazavi S, et al. Prevalence of HIV/HCV/HBV infections and drug-related risk behaviours amongst IDUs recruited through peer-driven sampling in Iran. Int J Drug Policy. 2010;21(6):493–500.

Ataei B, Meshkati M, Karimi A, Yaran M, Kassaian N, Nokhodian Z, et al. Hepatitis C screening in intravenuos drug users in Golpayegan, Isfahan through community announcement: pilot study. J Isfahan Med Sch. 2011;28:1581–6.

Azizi A, Amirian F, Amirian M. Prevalence and associated factors of hepatitis C in self-introduced substance abusers. Hayat. 2011;17(1):55–61.

Kaffashian A, Nokhodian Z, Kassaian N, Babak A, Yaran M, Shoaei P, et al. The experience of hepatitis C screening among prison inmates with drug injection history. J Isfahan Med Sch. 2011;28:1565–71.

Keramat F, Eini P, Majzoobi MM. Seroprevalence of HIV, HBV and HCV in persons referred to Hamadan behavioral counseling center, west of Iran. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2011;13(1):42–6.

Mir-Nasseri MM, Mohammadkhani A, Tavakkoli H, Ansari E, Poustchi H. Incarceration is a major risk factor for blood-borne infection among intravenous drug users: incarceration and blood borne infection among intravenous drug users. Hepat Mon. 2011;11(1):19–22.

Mobasheri zadeh S, Kassaian N, Ataei B, Nokhodian Z, Adibi P. Hepatitis C screening in intravenous drug users under treatment with methadone: an action reserch study. J Isfahan Med Sch. 2011;28:1572–6.

Amin-Esmaeili M, Rahimi-Movaghar A, Razaghi EM, Baghestani AR, Jafari S. Factors correlated with hepatitis C and B virus infections among injecting drug users in Tehran. IR Iran Hepat Mon. 2012;12(1):23–31.

Kassaian N, Adibi P, Kafashaian A, Yaran M, Nokhodian Z, Shoaei P, et al. Hepatitis C virus and associated risk factors among prison inmates with history of drug injection in Isfahan, Iran. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3(Suppl 1):S156–61.

Nobari RF, Meshkati M, Ataei B, Yazdani MR, Heidari K, Kassaian N, et al. Identification of patients with hepatitis C virus infection in persons with background of intravenous drug use: the first community announcement-based study from Iran. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3(Suppl 1):S170–S5.

Nokhodian Z, Ataei B, Kassaian N, Yaran M, Hassannejad R, Adibi P. Seroprevalence and risk factors of hepatitis C virus among juveniles in correctional center in Isfahan. Iran Int J Prev Med. 2012;3(Suppl 1):S113–7.

Nokhodian Z, Meshkati M, Adibi P, Ataei B, Kassaian N, Yaran M, et al. Hepatitis C among intravenous drug users in Isfahan, Iran: a study of seroprevalence and risk factor. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3(Suppl 1):S131–8.

Sarkari B, Eilami O, Khosravani A, Sharifi A, Tabatabaee M, Fararouei M. High prevalence of hepatitis C infection among high risk groups in Kohgiloyeh and Boyerahmad Province. Southwest Iran Arch Iran Med. 2012;15(5):271–4.

Sofian M, Aghakhani A, Banifazl M, Azadmanesh K, Farazi AA, McFarland W, et al. Viral hepatitis and HIV infection among injection drug users in a central Iranian city. J Addict Med. 2012;6(4):292–6.

Tavanaei Sani A, Khaleghinia M. Epidemiological evaluation and some species in injection drug users that admitted in infectious department of Imam Reza hospital. J Med Council Iran. 2012;30(2):155–61.

Honarvar B, Odoomi N, Moghadami M, Afsar Kazerooni P, Hassanabadi A, Zare Dolatabadi P, et al. Blood-borne hepatitis in opiate users in Iran: a poor outlook and urgent need to change nationwide screening policy. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e82230.

Ramezani A, Amirmoezi R, Volk JE, Aghakhani A, Zarinfar N, McFarland W, et al. HCV, HBV, and HIV seroprevalence, coinfections, and related behaviors among male injection drug users in Arak. Iran AIDS Care. 2014;26(9):1122–6.

Ziaee M, Sharifzadeh G, Namaee MH, Fereidouni M. Prevalence of HIV and hepatitis B, C, D infections and their associated risk factors among prisoners in southern Khorasan province. Iran Iran J Public Health. 2014;43(2):229–34.

Salehi A, Naghshvarian M, Marzban M, Bagheri LK. Prevalence of HIV, HCV, and high-risk behaviors for substance users in drop in centers in southern Iran. J Addict Med. 2015;9(3):181–7.

Afshari R, Fattahi M, Sepehrimanesh M, Safarpour AR, Nejabat M, Dehghani SM, et al. The seroepidemiology of hepatitis C infection in drug abusers referring to shiraz drug rehabilitation centers. Govaresh. 2016;21(3):188–93.

Rezaie F. Noroozi, Armoon B, Farhoudian a, Massah O, Sharifi H, et al. social determinants and hepatitis C among people who inject drugs in Kermanshah, Iran: socioeconomic status, homelessness, and sufficient syringe coverage. J Subst Abus. 2017;22(5):1–5.

Sharhani A, Mehrabi Y, Noroozi A, Nasirian M, Higgs P, Hajebi A, et al. Hepatitis C virus seroprevalence and associated risk factors among male drug injectors in Kermanshah. Iran Hepat Mon. 2017;17(10):e58739.

Behzadifar M, Gorji HA, Rezapour A, Bragazzi NL. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection among prisoners in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Harm Reduct J. 2018;15(1):24.

Behzadifar M, Gorji HA, Bragazzi NL. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in thalassemia patients in Iran from 2000 to 2017: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Virol. 2018;163(5):1131–40.

Behzadifar M, Gorji HA, Rezapour A, Bragazzi NL. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus among street children in Iran. Infect Dis Poverty. 2018;7(1):88.

Khodabandehloo M, Roshani D, Sayehmiri K. Prevalence and trend of hepatitis C virus infection among blood donors in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Res Med Sci. 2013;18(8):674–82.

Amon JJ, Garfein RS, Ahdieh-Grant L, Armstrong GL, Ouellet LJ, Latka MH, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection among injection drug users in the United States, 1994-2004. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(12):1852–8.

Scheibe A, Young K, Moses L, Basson RL, Versfeld A, Spearman CW, et al. Understanding hepatitis B, hepatitis C and HIV among people who inject drugs in South Africa: findings from a three-city cross-sectional survey. Harm Reduct J. 2019;16(1):28.

Waheed Y, Najmi MH, Aziz H, Waheed H, Imran M, Safi SZ. Prevalence of hepatitis C in people who inject drugs in the cities of Rawalpindi and Islamabad. Pakistan Biomed Rep. 2017;7(3):263–6.

Ray Saraswati L, Sarna A, Sebastian MP, Sharma V, Madan I, Thior I, et al. HIV, hepatitis B and C among people who inject drugs: high prevalence of HIV and hepatitis C RNA positive infections observed in Delhi. India BMC Public Health. 2015;15:726.

Alibrahim OA, Misau YA, Mohammed A, Faruk MB, Ss I. Prevalence of hepatitis C viral infection among injecting drug users in a Saudi Arabian hospital: a point cross sectional survey. J Public Health Afr. 2018;9(1):726.

Silva MB, Andrade TM, Silva LK, Rodart IF, Lopes GB, Carmo TM, et al. Prevalence and genotypes of hepatitis C virus among injecting drug users from Salvador-BA, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2010;105(3):299–303.

Millman AJ, Nelson NP, Vellozzi C. Hepatitis C: review of the epidemiology, clinical care, and continued challenges in the direct acting antiviral era. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2017;4(2):174–85.

Granados-García V, Flores YN, Díaz-Trejo LI, Méndez-Sánchez L, Liu S, Salinas-Escudero G, et al. Estimating the prevalence of hepatitis C among intravenous drug users in upper middle income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14(2):e0212558.

Grassi A, Ballardini G. Hepatitis C in injection drug users: it is time to treat. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(20):3569–71.

Matthews G, Kronborg IJ, Dore GJ. Treatment for hepatitis C virus infection among current injection drug users in Australia. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(Suppl 5):S325–9.

Liang TJ, Ward JW. Hepatitis C in injection-drug users - a hidden danger of the opioid epidemic. N Engl J Med. 20018;378(13):1169–71.

Saberi Zafarghandi MB, Jadidi M, Khalili N. Iran’s activities on prevention, treatment and harm reduction of drug abuse. Int J High Risk Behav Addict. 2015;4(4):e22863.

Rahimi-Movaghar A, Amin-Esmaeili M, Shadloo B, Noroozi A, Malekinejad M. Transition to injecting drug use in Iran: a systematic review of qualitative and quantitative evidence. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26(9):808–19.

Roy A, Praveen S, Devi KS, Haokip P, Laldinmawii G, Damrolien S. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and hepatitis C in people who inject drugs (PWID) and other high risk groups in a tertiary care hospital in Northeast India. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2017;4:3306–9.

Eckhardt B, Winkelstein ER, Shu MA, Carden MR, McKnight C, Des Jarlais DC, et al. Risk factors for hepatitis C seropositivity among young people who inject drugs in New York City: implications for prevention. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0177341.

Davis SM, Daily S, Kristjansson AL, Kelley GA, Zullig K, Baus A, et al. Needle exchange programs for the prevention of hepatitis C virus infection in people who inject drugs: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Harm Reduct J. 2017;14:25.

Platt L, Minozzi S, Reed J, Vickerman P, Hagan H, French C, et al. Needle syringe programmes and opioid substitution therapy for preventing hepatitis C transmission in people who inject drugs. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;18(9):CD012021.

Larney S, Kopinski H, Beckwith CG, Zaller ND, Jarlaid DD, Hagan H, et al. Incidence and prevalence of hepatitis C in prisons and other closed settings: results of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2013;58(4):1215–24.

Zampino R, Coppola N, Sagnelli C, Di Caprio G, Sagnelli E. Hepatitis C virus infection and prisoners: epidemiology, outcome and treatment. World J Hepatol. 2015;7(21):2323–30.

Dolan K, Wirtz AL, Moazen B, Ndeffo-Mbah M, Galvani A, Kinner SA, et al. Global burden of HIV, viral hepatitis, and tuberculosis in prisoners and detainees. Lancet. 2016;388(10049):1089–102.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MaB, MeB and NLB designed the study. MeB and MaB collected the data and performed the data analysis. All authors edited and revised the paper for grammar. All authors read and approved the final paper for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Behzadifar, M., Behzadifar, M. & Bragazzi, N.L. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in people who inject drugs in Iran. BMC Public Health 20, 62 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8175-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8175-1