Abstract

Background

Ethiopia has shown significant efforts to address the burden of TB/HIV comorbidity through the TB/HIV collaborative program. However, these diseases are still the highest cause of death in the country. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated this program by investigating the overall proportion of unknown HIV status among TB patients using published studies in Ethiopia.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of published studies in Ethiopia. We identified the original studies using the databases MEDLINE/PubMed, and Google Scholar. The heterogeneity across studies was assessed using Cochran’s Q test and I 2 statistics. The Begg’s rank correlation and the Egger weighted regression tests were assessed for the publication bias. We estimated the pooled proportion of unknown HIV status among TB patients using the random-effects model.

Results

Overall, we included 47 studies with 347,896 TB patients eligible for HIV test. The pooled proportion of unknown HIV status among TB patients was 27%(95% CI; 21–34%) and with a substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 99.9%). In the subgroup analysis, the pooled proportion of unknown HIV status was 39% (95% CI; 25–54%) among children and 20% (95% CI; 11–30%) among adults. In the region based analysis, the highest pooled proportion of unknown HIV status was in Gambella, 38% (95% CI; 16–60%) followed by Addis Ababa, 34%(95% CI; 12–55%), Amhara,30%(95% CI; 21–40%),and Oromia, 23%(95% CI; 9–38%). Regarding the study facilities, the pooled proportion of unknown HIV status was 33% (95% CI; 23–43%) in the health centers and 26%(95% CI; 17–35%) in the hospitals. We could not identify the high heterogeneity observed in this review and readers should interpret the results of the pooled proportion analysis with caution.

Conclusion

In Ethiopia, about one-third of tuberculosis patients had unknown HIV status. This showed a gap to achieve the currently implemented 90–90-90 HIV/AIDS strategic plan in Ethiopia, by 2020. Therefore, Ethiopia should strengthen TB/HIV collaborative activities to mitigate the double burden of diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and tuberculosis (TB) co-infection represent a significant cause of morbidity and mortality. This is in part due to the shared nature of immune defense against the two diseases [1, 2]. Low-income countries, the African continent with 74% new TB/HIV co-infection rate, take a great share of TB/HIV cases worldwide [3].

The World Health Organization (WHO), recognizing the synergistic effect of these diseases, recommended a framework of TB/HIV collaborative strategic program carried out across the health facilities [4]. These include routine testing of all TB patients for HIV, symptomatic TB screening of HIV patients, and early initiation of prophylaxis and treatment [5, 6]. Many countries implemented this program record a significant improvement, but less than half of all TB patients tested for HIV infection worldwide [7].

Ethiopia adopted this global recommendation early and embarked on the service (by establishing HIV/TB Advisory Committee) since 2002. The program expanded across the health facilities for the last one and half decades [8, 9]. A recent national report, however, found that up to 19% of TB patients did not know their HIV status, and a significant variation (0–24%) was observed across the regions [10]. The success, sustainability and coverage of this program, also the millennium development goal completed in 2015 [11], has been challenged. The problem might be related to the programs multifaceted nature with the sharing project mode approaches and their funding dependent on HIV-related indicators [12].

Currently, the country implemented the 90–90-90 HIV/AIDS global strategy that calls for 90% of HIV-infected individuals to be diagnosed by 2020, 90% of whom will be on antiretroviral therapy (ART) and 90% of whom will attain sustained biological suppression [13]. However, the trend of HIV/AIDS for the last 26(1990–2016) years and predicting achievement of the 90–90-90 HIV prevention targets found that, Ethiopia is not in a good position to achieve the first target for HIV diagnosis [14, 15].

Unknown HIV status among tuberculosis patients could be a potential source of the ongoing increase in the disease. It also destabilizes HIV control programs practiced throughout the country. To our knowledge, there is no comprehensive published data assessing the unknown HIV status among TB patients since the TB/HIV program has been implemented in Ethiopia. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis determined the magnitude of unknown HIV status among TB patients. It also assessed variation of unknown HIV status across the regions and health settings in the country. For this purpose, we reviewed published studies conducted using TB/HIV routine data in Ethiopia.

Methods

Study design and data sources

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of published studies in Ethiopia to estimate the proportion of unknown HIV status among TB patients after the HIV/TB collaborative approach was started. For this, we searched original articles using MEDLINE/PubMed, Embase, Cochrane library, and Google scholar databases. Besides, we made a hand search for cross-referencing the identified original articles. To report the results of the current meta-analysis, we used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [16]. The electronic search was performed using a combination of keywords in the MEDLINE/PubMed database using the Medical Science Heading (MeSH) terms [(Tuberculosis OR TB [MeSH Terms)] AND (HIV OR AIDS [MeSH Terms] OR HIV/AIDS [MeSH Terms] OR ‘Human immunodeficiency virus’ [MeSH Terms] OR ‘Human Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome’[MeSH Terms]) AND (Retrospective) AND (Ethiopia)]. We included articles published in English language and among humans. The review comprised studies conducted between 2002 and 2019. We did the last search on 30 September 2019.

Study selection

In the first stage, we reviewed the titles and abstracts of all retrieved articles addressing the study questions and grouped them as eligible. In the second stage, we evaluated each article in detail against the inclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were:-a published study in Ethiopian after 2002, retrospective studies using routine data, reported quality control/assurance measures, and report the HIV status of TB patients. We excluded studies with a prospective study design (collected data for research purpose), done among known HIV patients, and reviews that reiterated findings from the already included studies. Two authors (BA and GM) conducted the articles selection and any disagreement resolved through discussion.

Study quality assessment

We tested the quality of the included studies using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) appraisal tool for prevalence studies [17]. The tool has nine appraisal criteria and for each criterion,'Yes’, ‘No’, or ‘Unclear’ were likely responses. An article fulfilled the evaluation criteria ‘yes’ answer received 1 point; otherwise, it scored 0 points. After the evaluation, we included articles with a high-quality score that fulfilled more than half of the evaluation JBI criteria.

Data extraction

With the help of a standardized data abstraction format prepared in Microsoft Excel, two authors (BA and GM) extracted important data related to study characteristics. This includes the title, first author, publication year, year of study, design of the study, regions of study (study site in the country), HIV status (positive, negative, or unknown), study settings (hospitals, health centers), the total number of tuberculosis cases, types of tuberculosis (Acid fast bacilli (AFB)-positive, AFB-negative, extrapulmonary cases (EPTB)), the data type, and age groups of patients. The authors (BA and GM) extracting the data, solved any disagreement that happened through discussion and consensus.

Statistical analysis

We extracted the data and analysed using Stat version 14 software. Then, we presented a detailed description of the original studies in a table and forest plot. We determined the pooled estimate of the proportion of unknown HIV status using the DersimonianLaird for random-effects meta-analysis (random effects model). The proportion of unknown HIV status among tuberculosis was measured with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We used Arcsine transformation and presented the results on the original probability scale after using the corresponding back-transformation [18].

We tested the potential source of publication bias and heterogeneity across studies using the Cochrane Q test (presence of heterogeneity) and I2 statistics (amount of heterogeneity). To check the presence of heterogeneity, we used the Cochrane Q test and significant heterogeneity taken when P < 0.10. The I2 was used to measure the level of heterogeneity between studies with the values of 25, 50, and 75% which is to mean low medium, and high heterogeneity, respectively [19]. We also used the Begg’s rank correlation test and Egger weighted regression tests to determine the publication bias. A significant publication bias considered if p < 0.05.

We did a sensitivity test to indicate which study is the prime determinant of the pooled result, and the principal source of heterogeneity. The test exclude each study one by one in the analysis to show the change in pooled effect size and associated heterogeneity. If the point estimate of pooled prevalence after dropping a study lies within the 95% CI of the overall pooled estimate for all studies combined, we considered the study has a non-important influence on the overall pooled estimate [20].

We planned subgroup analysis at the point of designing the study to investigate the source of heterogeneity based on administrative regions, study setting, age groups, and TB types. The minimum number of studies should be at least two in each subgroup analysis.

Results

Search results

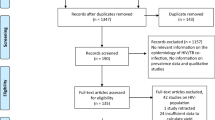

Overall, we retrieved 1315 potential articles using key terms and/or phrases. Of these, 93 full-text articles were reviewed in detail and the rest were excluded either due to duplicated title, or accessed only in the abstract. Here again, after a careful evaluation using inclusion criteria, we included only 47 studies for the final meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

Characteristics of the included studies

A total of 347,896 TB patients were identified among the 47 included articles. The articles were published between 2010 to 2019 and undertaken between 2002 to 2017. Forty-two [21,22,23,24,25,26, 28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62] of studies used data collected before 2015 and remaining four studies [27, 63,64,65,66] from 2015 to 2017. The sample size of the studies varying from 162 [32] to 272,526 [45]. In this meta-analysis, eight of the nine regions and one of the two city administrative in Ethiopia represented. Sixteen of the studies were from Amhara region [31,32,33,34, 36, 39, 42, 44, 46, 48, 49, 51, 53, 57, 62, 65], eleven from Oromia region [23, 25, 28, 29, 41, 45, 49, 50, 59, 61, 66], six from Addis Ababa city [26, 27, 38, 40, 54, 63] and the rest from other regions. We identified three studies among children [26, 38, 56], and, three among adults [22, 32, 49], and the remaining 41 among all age groups (Table 1).

The majority (n = 38) of the studies conducted among different types of TB and only nine studies [27, 34, 37, 40, 44, 45, 54, 64, 65] among pulmonary TB (PTB). Based on the Acid Fast Staining (AFB), the proportion of AFB positive and AFB negative ranged from 9% [35] to 84% [26], and 8% [26] to 66% [60] respectively. The proportion of the EPTB varied from 8% [26] to 25% [60]. With regard to HIV infection status among TB patients, the HIV-positive ranged from 2% [25] to 44% [53], HIV-negative ranged from 4% [27] to 95% [24], and unknown HIV status ranged from 1% [24] to 90% [27].

Quality of the included studies

We assessed the quality of all studies using the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for prevalence studies. Based on the assessment, all the included studies scored over 60% (6/9), and none of the included studies were deemed of poor quality and excluded (Additional file 1).

Meta-analysis

Heterogeneity and publication bias

We assessed for heterogeneity and publication bias of 47 studies. The analysis showed substantial heterogeneity of the Q test (p < 0.001) and I2 statistics (I2 = 99.9%). A funnel plot for the publication bias was not symmetrical (Fig. 2). However, we did not find evidence of publication bias using Egger’s test (P = 0.94).

Unknown HIV status among tuberculosis patients

We presented the proportion of unknown HIV status among TB patients in a forest plot (Fig. 3). The overall pooled proportion of unknown HIV status from the random-effects model was 27% (95% CI; 21–34, I2 = 99.9%, p < 0.001) (about 73% had known status).

Subgroup analysis

In a subgroup analysis by region, the pooled proportion of unknown HIV status was highest in Gambella, 38% (95% CI; 16–60%) followed by Addis Ababa, 34% (95% CI; 12–55%) and Amahara region, 30% (95% CI; 21–40). As shown in Fig. 4, the lowest pooled proportion Unknown HIV status was in Tigray region, 19% (95% CI;3–38). Another subgroup analysis by setting, the pooled proportion of unknown HIV status was 33% (95% CI; 23–43%) in the health centers alone and 26% (95% CI;17–35%) in hospitals (Fig. 5). According to the anatomical classification of TB, the pooled proportion of unknown HIV status was 33% (95% CI; 20–47) among pulmonary tuberculosis and 26% (95% CI; 20–32) among all types of TB patients (Fig. 6). The age-based analysis showed that the pooled proportion of unknown HIV status was 39% (95% CI; 25–54) and 20% (95% CI; 11–30) among children (< 15 years) and adults (Fig. 7).

Sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity analysis revealed that our findings were robust and not dependent on a single study. The pooled estimated prevalence varied between 26% (20–34%) and 28% (21–34%) after a single study deleted (See Additional files 2).

Discussion

As WHO recommended, routine testing of tuberculosis patients for HIV is crucial in HIV epidemic countries like Ethiopia. This is crucial to monitor and assess the HIV/TB collaborative prevention and care programs [6]. In this review, we found that the pooled proportion of unknown HIV status among TB patients was 27%. This is higher than the national HIV/TB surveillance (including 79 senile sites) that reported 89% of TB patients were screened for HIV [68]. In this surveillance, the investigators trained the data collectors, they prepared standardized data collection guidelines and supervised the data collection process. This might be the reason for the lower level of unknown HIV status among tuberculosis patients in national surveillance, unlike our findings. Another meta-analysis of 13 studies in Ethiopia, amid to assess the prevalence of HIV among TB patients, reported a lower prevalence rate (6.4%) of unknown HIV status compared to our findings [69]. The differencemight be related to the number of studies included or because they included prospective studies in their review. In cases, a study in Malawi showed that the routine HIV testing among TB patients was above 90% under research conditions, but lower (59%) with routine care conditions [70]. Ethiopia adopted the global 90–90-90 targets (2018–2020) with 90% of people with HIV know their status [71], but the current pooled analysis showed that there is major gap in achieving this target. The problem might be because of a weak health care system or lack of education and health service support, poor access, or lack of availability of screening materials.

In the subgroup analysis, we identified a high proportion of unknown HIV status in Gambella (38%) and Addis Ababa city (34%) compared to the other regions included in the reviews. The three (2005, 2011, and 2016) Ethiopian demographic health surveys reported the highest prevalence rate of HIV in Gambella and Addis Ababa [72]. Thus, the findings of this review showed a higher number of HIV-positive patients that were missed in these regions.

The pooled proportion of unknown HIV status is higher in health centres (33%) than in hospitals (26%). In Ethiopia, AFB-negative TB patients with typical clinical symptoms who do not respond to a trial antibiotic treatment and all AFB–Positive TB patients are treated with anti-TB at health centers. However, critically ill TB patients, TB patients with TB treatment history or presumptive drug-resistant TB, and EPTB patients are referred to the next level health facilities (primary, general, or tertiary hospital). Here, the patients are further investigated for comorbid conditions including HIV. This might be the potential reason for lower level of unknown HIV status in hospitals compared to health centers. The variation across the health settings for the same program might also relate to lack of counselling and testing service, poor behavioural change, or poor integration of the program in to the health system.

In this review, unknown HIV status among children (< 15 years) was higher than adults (39% vs. 20%). Similarly, HIV testing among children versus adults with TB in Vietnam revealed that about 70% of children had incomplete HIV test documentation [73]. In our country, testing children for HIV, including TB patients, is focused on the HIV serostatus of parents. This approach may miss other than parent to child (vertical) HIV transmission in adolescent age groups.

This is the first review aimed to determine the proportion of unknown HIV status among TB patients since the national HIV/TB collaborative activities initiated. All the studies included in the review fulfilled more than half of the JBI quality assessment check criteria, with no study excluded because of poor quality scores. As the HIV pandemic continues to fuel the global tuberculosis epidemic, including in Ethiopia, such review is significant to provide comprehensive data about HIV status among patients with TB and shows priority study area to investigate potential sources for the spread of HIV to the general population.

This study has certain limitations. As all the studies included were retrospective, this may overestimate the pooled proportion of unknown HIV status among tuberculosis patients. We detected high levels of heterogeneity across all the analyses and readers should interpret the pooled analysis and subgroup with caution.

Conclusion

In this review about one-third of TB patients had unknown HIV status in Ethiopia. This showed a gap to achieve the national 90–90-90 HIV/AIDS strategic plan, which is expected to be achieved by 2020 and eliminate the HIV epidemic by 2030. Therefore, it is essential to strengthen TB/HIV collaborative program in Ethiopia in order to reduce the potential source for the ongoing HIV transmission. Additional researches, mainly longitudinal studies, should be a key priority to investigate factors for the unknown HIV status and the variations across the health settings, regions, types of tuberculosis,and age groups.

Availability of data and materials

All the data and materials are available and available to any researcher wishing to use them.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- TB:

-

Tuberculosis

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization?

References

WHO. Guidelines for HIV surveillance among tuberculosis patients. 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004.

WHO. Global tuberculosis report. Geneva; 2017. p. 2017.

Mayer KH, Hamilton CD. Synergistic pandemics: confronting the global HIV and Tuberculosis epidemics. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:S67–70.

WHO. A strategic framework to decrease the burden of TB/HIV. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002.

Sendagire I, Schreuder I, Mubiru M, et al. Low HIV testing rates among tuberculosis patients in Kampala, Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):177.

WHO. WHO policy on collaborative TB/ HIV activities: guidelines for national programs and other stakeholders. WHO/HTM/TB/2004.330. Geneva: WHO; 2012.

WHO. Global Tuberculosis Control: WHO report 2016 (WHO/HTM/TB/2016.13). Geneva: WHO; 2016.

The Federal Ministry of Health of Ethiopia. Implementation Guideline for TB/HIV Collaborative Activities in Ethiopia. 2007.

The Federal Ministry of Health of Ethiopia. TB/HIV implementation guideline 2008. Addis Ababa: Ministry of Health; 2008.

Assefa Y, Gilksa FC, Judith Deana J. Towards achieving the fast-track targets and ending the epidemic of HIV/AIDS in Ethiopia: Successes and challenges. Int J Infect Dis. 2019;78:57–64.

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). UNAIDS Data 2017.

Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI). Report on National TB/HIV Sentinel Surveillance (April 2010–June 2015). 2015.

Joint United Nations programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). 90–90-90: an ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/ AIDS (UNAIDS); 2014.

Girum T, Wasie A, Worku A. Trend of HIV/AIDS for the last 26 years and predicting achievement of the 90-90-90 HIV prevention targets by 2020 in Ethiopia: a time series analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18:320.

Jamieson D and Kellerman S. The 90 90 90 strategies to end the HIV Pandemic by 2030: Can the supply chain handle it Journal of the International AIDS Society 2016; 19:20917.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis: the Prisma statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(6):e1000097.

The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal tools for JBI Systematic Reviews. Checklist for Prevalence Studies: Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017.

Freeman MF, Tukey JW. Transformations related to the angular and the square root. Ann Math Stat. 1950;21:607–11.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analysis. BMJ. 2003;327:557.

Viechtbauer W, Cheung MWL. Outlier and influence diagnostics for Meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2010:112–25.

Mondale B, Medihn G, Teklu T, et al. A retrospective study on tuberculosis treatment outcomes at Jinka general hospital, southern Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10:680.

Adane K, Spigt M, Dinant GJ. Tuberculosis treatment outcome and predictors in northern Ethiopian prisons: a five-year retrospective analysis. BMC Pulm Med. 2018;18:37.

Ejeta E, Chala M, Gebeyaw AG, et al. Outcome of Tuberculosis patients under observed short-course treatment in western Ethiopia. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2015;9(7):752–9.

Getnet F, Sileshi H, Seifu W, et al. Do retreatment tuberculosis patients need special treatment response follow-up beyond the standard regimen? Finding of a five-year retrospective study in pastoralist setting. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17:762.

Ramos JM, Reyes F. Tesfamariam A children and adult tuberculosis in a rural hospital in Southeast Ethiopia: a ten-year retrospective study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:215.

HailuD AW, Belay M. Childhood tuberculosis and its treatment outcomes in Addis Ababa: a 5-years retrospective study. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:61.

Arega B, Menbere F, Getachew Y. Prevalence of rifampicin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis among presumptive tuberculosis patients in selected governmental hospitals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:307.

Gebremariam G, Asmamaw G, Hussen M, et al. Impact of HIV status on treatment outcome of Tuberculosis patients registered at ArsiNegele health center, southern Ethiopia: a six-year retrospective study. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):144–6.

Tafess K, Beyen TK, Abera A, et al. Treatment outcomes of Tuberculosis at Asella teaching hospital, Ethiopia: Ten Years’ Retrospective Aggregated Data. Front Med. 2018;5:38.

Birlie A, Tesfaw G, Dejene T, Woldemichael K. Time to death and associated factors among Tuberculosis patients in DangilaWoreda, Northwest Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):1–10.

Melese A, Zeleke B. Factors associated with poor treatment outcome of tuberculosis in Debre Tabor, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):451–3.

Berihun Y, Nguse T, Gebretekle G. Prevalence of Tuberculosis and treatment outcomes of patients with Tuberculosis among inmates in Debrebirhan prison, north Shoa Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2017;28(3):347.

Endris M, Moge F, Belyhun Y. Treatment Outcome of Tuberculosis Patients at Enfraz Health Center, Northwest Ethiopia: A Five-Year Retrospective Study. Hindawi; 2014. ID 726193.

Jaleta KJ, Baye MG, Gelaw GB. Rifampicin-resistant mycobacterium tuberculosis among tuberculosis-presumptive cases at the University of Gondar Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Infect Drug Resist. 2017;10:185–92.

Simieneh A, Hailemariam M, Amsalu A. HIV screening among TB patients and level of antiretroviral therapy and co-trimoxazole preventive therapy for TB/HIV patients in Hawassa University Referral Hospital: a five-year retrospective study. Pan Afri Med J. 2017;28:75.

Mekonnen D, Derbie A, Mekonnen H, et al. Profile and treatment outcomes of patients with tuberculosis in northeastern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Afr Health Sci. 2016;16(3):663–70.

Berhe G, Enquselassie F. AseffaA. Treatment outcome of smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Tigray region, northern Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:537.

Tilahun G, GebreSelassie S. Treatment outcomes of childhood tuberculosis in Addis Ababa: a five-year retrospective analysis. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:612.

Zenebe Y, AdemY MD. Profile of tuberculosis, and its response to anti-TB drugs among tuberculosis patients treated under the TB control program at FelegeHiwot Referral Hospital, Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:688.

Assefa D, Seyoum B, Oljira L. Determinants of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Infect Drug Resist. 2017;10:209–21.

Sintayehu W, Abera A, Gebru T, et al. Trends of Tuberculosis treatment outcomes at Mizan-Aman general hospital, Southwest Ethiopia: a retrospective study. Int J Immunol. 2014;2:11–5.

Tefera F, Dejene T, Tewelde T. Treatment outcomes of Tuberculosis patients at DebreBerhan hospital, Amhara region, northern Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2016;26(1):125–7.

Asebe G, Dissasa H, Teklu T, et al. Treatment outcome of Tuberculosis patients at Gambella hospital, Southwest Ethiopia: Three-year Retrospective Study. J Infect Dis Ther. 2015;3:211.

Kebede ZT, Taye BW, Matebe YH. Childhood tuberculosis: management and treatment outcomes among children in Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Pan African Medical Journal. 2017;27:25.

Sisaya S, Mekonen A, Abera A. An evaluation of collaboration in the TB and HIV control program in Oromia region, Ethiopia: seven years of retrospective data. Int J Infect Dis. 2018;77:74–81.

Biruk M, Yimam B, Abrha H. Treatment Outcomes of Tuberculosis and Associated Factors in an Ethiopian University Hospital: Hindawi; 2016. ID 8504629.

Yakob B, Alemseged F, Paulos W, Badacho AS. Trends in treatment success rate and associated factors among Tuberculosis patients in Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. Health Sci J. 2018;12(5):598.

Addis Z, Birhan W, Alemu A. Treatment outcome of Tuberculosis patients in Azezo health center, North West Ethiopia. IJBAR. 2013;04(03):121–4.

Yadetaa D, Alemsegedb F, Biadgilign S. Provider-starting HIV testing and counseling among tuberculosis patients in a hospital in the Oromia region of Ethiopia. J Infect Public Health. 2013;6:222–9.

Akessa GM,Tadesse M,Abebe G. Survival Analysis of Loss to Follow-Up Treatment among Tuberculosis Patients at Jimma University Specialized Hospital, Jimma, Southwest Ethiopia. Hindawi 2015; ID 923025.

Yilma M. The effect of Hiv co-infection on Tuberculosis treatment in a zonal referral hospital in Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. Ethiop Med J. 2019;57(1):141–3.

Ayele B, Nenko G. Treatment outcome of Tuberculosis in selected health facilities of Gedeo zone, Southern Ethiopia: A Retrospective Study. Mycobact Dis. 2015;5:194.

Woldeamanuel GG, Mingude AB. Factors associated with mortality in Tuberculosis patients at Debrebirhan referral hospital, Ethiopia: A Retrospective Study. J Trop Dis. 2018;7:289.

Demile B, Zenebu A, Shewaye H. Risk factors associated with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) in a tertiary armed force referral and teaching hospital, Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18:249.

Zenebe T, Genet C, Tefera E, et al. Effectiveness of observed treatment, short-course (DOTS) on the treatment of tuberculosis patients in the Afar region, Ethiopia. Int J Health Sci Res. 2016;6(8):112–8.

Asres A, Jerene D, Deressa W. Tuberculosis treatment outcomes of six and eight-month treatment regimens in districts of Southwestern Ethiopia: a comparative cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:653.

GebreegziabherSB YSA, Bjune GA. Tuberculosis case notification and treatment outcomes in west Gojjam zone, Northwest Ethiopia: a five-year retrospective study. J Tuberc Res. 2016;4:23–33.

Asebe G, Ameni G, Tafess K. Ten years tuberculosis trend in Gambella regional hospital, South Western Ethiopia. Malays J Med Biol Res. 2014;1(1):156–8.

Abebe T, Angamo MT. Treatment outcomes and associated factors among tuberculosis patients in Southwest Ethiopia. Gülhane Tıp Derg. 2015;57:397–407.

Alemu J, Mamo G, Kandi V, et al. Prevalence of Tuberculosis in Gambella regional hospital, Southwest Ethiopia: a retrospective study to assess the Progress towards millennium development goals for Tuberculosis (2006-2015). Am J Public Health Res. 2017;5(1):6–11.

Tachbele E, Taye B, Tulu B, et al. Treatment outcomes of Tuberculosis patients at bale robe hospital, Oromia regional state, Ethiopia: A Five Year Retrospective Study. J Nurs Care. 2017;6:386.

Tarekehne D, Jema M, Atenaw T. Prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus in the court of tuberculosis at MetemaHospital, northwest Ethiopia: A 3-year retrospective study. BMC Res Note. 2016;9:192.

Worku Y, Getinet T, Mohammed S, Yang Z. Drug-resistant Tuberculosis in Ethiopia: characteristics of cases in a referral hospital and the implications. Int J Mycobacterial. 2018;7:167–72.

Ejetab E, Beyenea G, Bonsa Z. Xpert MTB/RIF assay for the diagnosis of mycobacterium tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance in high human immunodeficiency virus setting in Gambella regional state, Southwest Ethiopia. J ClinTuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2018;12:14–20.

Shibabaw A, Gelaw B, Wang S-H, Tessema B. Time to sputum smear and culture conversions in multidrug-resistant tuberculosis at the University of Gondar Hospital Northwest Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):203–6.

Muluye AB, Kebamo S, Teklie T, et al. Poor treatment outcomes and its determinants among tuberculosis patients in selected health facilities in east Wollega, Western Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0206227.

Amante TD, Ahmed TA. Risk factors for unsuccessful tuberculosis treatment outcome (failure, default, and death) in public health institutions, Eastern Ethiopia. Pan Afri Med J. 2015;20:247.

Tuberculosis S. Guidelines for surveillance HIV among TB patients. 2nd ed. Geneva: TB/HIV working group of the Global Partnership to Stop TB, World Health Organization; 2004.

Endalamaw A, Ambachew S, Geremew D. HIV infection and unknown HIV status among tuberculosis patients in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2019;23(2):187–94.

Chimzizi R, Harries A, Manda E, Khonyongwa A, Salaniponi F. Counseling, HIV testing, and adjunctive cotrimoxazole for TB patients in Malawi: from research to routine implementation. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004;8(8):938–44.

HIV Prevention in Ethiopia National Road Map 2018–2020. Available: https://ethiopia.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf: Accessed; Nov 30/2019.

Kibret GD, Ferede A, Leshargie CT, Wagnew F. Trends, and spatial distributions of HIV prevalence in Ethiopia. Infect Dis Poverty. 2019;8:90.

Volkmann T, Nguyen B, Ebelechukwu G. Comparison of HIV testing among children and adults with Tuberculosis. Vietnam. J Tuberc Res. 2017;5(4):292–7.

Acknowledgments

No special thank.

Funding

The authors declare that they did not receive funding for this research from any source.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BA contributed to the design of the study, collected, entered, analyzed, and interpreted the data; and prepared the paper. AM contributed to the conception and design of the study, collected, and drafted the paper. AA contributed to the conception and design of the study, interpretation, and drafted the paper. GM contributed to the interpretation and data analysis by reviewing the results. ME helped to interpret the results, and in drafting and reviewing the paper. All authors read and approved the last paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study is based on a systematic review of published data and thus does not require ethical clearance

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Quality of studies included in the meta analysis tassese the proportion of unknown HIV status among patients with tuberculosis

Additional file 2.

Sensitivity analysis of the proportion of unknown HIV status among patients with tuberculosis

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Arega, B., Minda, A., Mengistu, G. et al. Unknown HIV status and the TB/HIV collaborative control program in Ethiopia: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 20, 1021 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09117-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09117-2