Abstract

Background

Socioeconomic disadvantage is a fundamental cause of morbidity and mortality. One of the most important ways that governments buffer the adverse consequences of socioeconomic disadvantage is through the provision of social assistance. We conducted a systematic review of research examining the health impact of social assistance programs in high-income countries.

Methods

We systematically searched Embase, Medline, ProQuest, Scopus, and Web of Science from inception to December 2017 for peer-reviewed studies published in English-language journals. We identified empirical patterns through a qualitative synthesis of the evidence. We also evaluated the empirical rigour of the selected literature.

Results

Seventeen studies met our inclusion criteria. Thirteen descriptive studies rated as weak (n = 7), moderate (n = 4), and strong (n = 2) found that social assistance is associated with adverse health outcomes and that social assistance recipients exhibit worse health outcomes relative to non-recipients. Four experimental and quasi-experimental studies, all rated as strong (n = 4), found that efforts to limit the receipt of social assistance or reduce its generosity (also known as welfare reform) were associated with adverse health trends.

Conclusions

Evidence from the existing literature suggests that social assistance programs in high-income countries are failing to maintain the health of socioeconomically disadvantaged populations. These findings may in part reflect the influence of residual confounding due to unobserved characteristics that distinguish recipients from non-recipients. They may also indicate that the scope and generosity of existing programs are insufficient to offset the negative health consequences of severe socioeconomic disadvantage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Decades of epidemiological research has demonstrated that socioeconomic resources such as wealth, income, and employment – often referred to as the social determinants of health – are “fundamental causes” of health inequalities [1, 2]. They are fundamental in the sense that they influence the everyday conditions, experiences, and exposures that influence health status. Put simply, those with fewer socioeconomic resources get sicker and die sooner than those higher up in the socioeconomic hierarchy. These findings have led to a broad consensus in the field of public health: social policies that shape the extent to which socioeconomic advantage and disadvantage occur in society offer the most effective, if politically contentious, strategy for reducing health inequalities [3]. Indeed, the final report of the World Health Organization Commission on the Social Determinants of Health concluded that the emphasis in public health must shift from individual-level interventions that aim to modify people’s behaviours to societal-level interventions that ameliorate their everyday socioeconomic conditions [4].

One of the most important ways that societies intervene to buffer the adverse consequences of socioeconomic disadvantage is through the provision of social assistance [5]. Social assistance refers to government programs that provide a minimum level of income support to individuals and households living in poverty. These programs lend support either in the form of direct cash transfers or through a variety of in-kind benefits (e.g. food stamps and rent subsidies). Social assistance has been shown to strengthen the purchasing power of the poor and raise their material standards of living [6, 7]. From a public health point of view, the supplemental provision of income can also enable people to avoid harmful exposures and adopt practices beneficial to their health [8]. Thus, theory predicts that social assistance programs offer an important means of protecting the health of socioeconomically disadvantaged groups and mitigating the extent of socioeconomic health inequalities [9, 10].

While there is widespread theoretical support for the role of social assistance as a policy lever with which to improve population health and promote health equity, it is unclear what the extant evidence demonstrates empirically. At the same time, there is growing concern that existing programs provide insufficient levels of protection and that such inadequacies in the social safety net produce extraordinary costs, both human and economic [11,12,13]. Such concern has, in some cases, prompted calls for a major overhaul of traditional social assistance schemes. In Canada, Finland, and the Netherlands, for example, governments have conducted small-scale experiments to explore the potential benefits of alternative systems of income provision, such as unconditional basic income [14]. At this critical juncture, there is a need to take stock of the extent to which existing social assistance programs are succeeding (or not) at promoting population health and health equity.

Given the clear implications of recent political developments for the health of socioeconomically vulnerable populations and the lack of clarity on the state of the extant evidence, our aim in this paper is to conduct a systematic review of peer-reviewed research that has examined the health impact of social assistance programs. We focus on programs that provide direct financial assistance rather than aid in the form of in-kind benefits. Previous reviews have evaluated the health impact of other sources of income maintenance, including food stamps [15], low-income tax credits [16], minimum wage laws [17], and unemployment insurance systems [18]. Furthermore, to avoid overlap with similar reviews in low- and middle-income countries [19], we restrict our analysis to high-income countries with well-established welfare state systems (i.e. Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, United States). To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to evaluate the health impact of social assistance transfers in high-income countries.

Methods

Search strategy

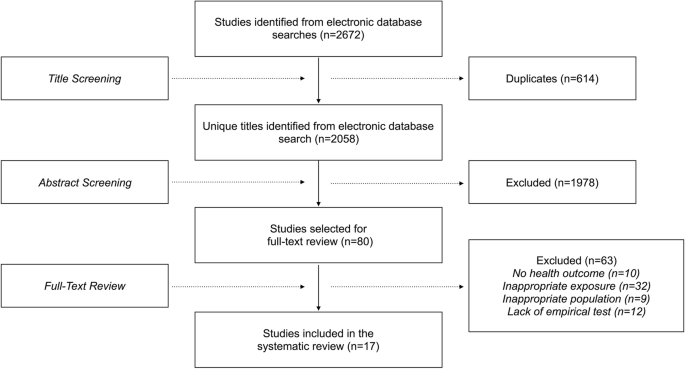

We conducted a systematic search of the literature in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The search protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42016048078). The search terms are listed in Table 1. We searched the following electronic databases from inception to December 31, 2017: Embase, Medline, ProQuest, Scopus, and Web of Science. We supplemented our electronic search by handsearching the reference lists of all included literature and related review articles. We restricted our search to English-language publications in peer-reviewed scientific journals. Grey literature, working papers, and peer-reviewed commentaries lacking direct empirical tests were excluded. Two authors conducted separate searches. Disagreements were resolved as a team through discussion and consensus.

The initial search yielded 2058 unique articles. Abstracts were screened to determine their eligibility for full-text review. Eligibility was determined based on four inclusion criteria: (i) reference to a social assistance program; (ii) reference to a health outcome, major risk factor for disease (e.g. hypertension and obesity), or health behaviour (e.g. smoking and diet); (iii) reference to an appropriate study population (i.e. working-age adults between 18 and 64 years of age); and (iv) reference to an empirical method of testing the health impact of social assistance or social assistance reform. We excluded studies that examined health care outcomes (e.g. health insurance coverage and physician visits) which require a distinct theoretical orientation. We also excluded studies examining maternal and child health outcomes, as these have been reviewed elsewhere [20]. Two authors marked each abstract as “Yes” if they satisfied all four inclusion criteria, “Maybe” if they satisfied two or three of the criteria; and “No” if they satisfied fewer than two of the criteria. Abstracts marked as “Yes” or with at least one “Maybe” were subject to full-text review.

Data extraction and analytic strategy

A standardized form was used to extract relevant data from the included studies. We extracted the following information from each study: title, authors, year of publication, country, data source, sample size, main research question, study design, health outcome, and main findings. Two authors extracted the data independently. The results of the extraction were shared and discussed with the entire research team. Disagreements were resolved as a team through discussion and consensus. The extracted data was used to summarize the key features of the selected literature and synthesize the available evidence across studies. The entire research team collaborated to identify empirical patterns based on this summary and synthesis.

Quality assessment

We assessed the quality of studies using a modified version of the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies developed by the National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools. [21] We describe our method of assessment in greater detail in Additional file 1. We rated studies according to five criteria: (i) Did the study draw on a representative sample? (ii) Did the study describe the characteristics of the exposed and unexposed groups? (iii) Did the study adopt a descriptive cross-sectional, descriptive longitudinal, quasi-experimental, or experimental study design? (iv) Did the study control for important confounders such as age, gender, marital status, and education? (v) Did the study document and account for attrition (only if longitudinal). On each criterion, studies were rated as either ‘strong’, ‘moderate’, or ‘weak’. A global quality rating was derived based on whether studies had no weak ratings (‘strong’), one weak rating (‘moderate’), or two or more weak ratings (‘weak’).

Results

Literature search

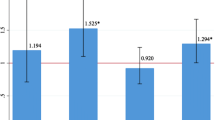

In Fig. 1, we summarize the results of our search strategy. Of the 2058 unique abstracts identified, eighty studies were selected for full-text review. Upon further examination, seventeen studies were found to meet our inclusion criteria. Their primary characteristics are listed in Table 2 and described in further detail below.

Data sources and population characteristics

Most of the studies involved secondary analyses of nationally representative survey data [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. Two relied on population-based administrative data [36, 37]. A final study drew from a smaller community cohort study [38]. With respect to study populations, ten of the studies looked at the general working-age population [22, 24, 25, 27, 29, 30, 32,33,34,35]. Another focused only on women [26]. Two restricted their analyses to socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals within the working-age population [36, 37]. The other four further restricted their analyses to socioeconomically disadvantaged women [23, 28, 31, 38]. The studies showed a high degree of geographic concentration. Nine of the seventeen studies were based in the United States [23, 26, 28, 31, 33, 34, 36,37,38]. Of the remaining eight studies, five were situated in other English-speaking liberal political economies characterized by weakly redistributive social policies, Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom [24, 25, 27, 29, 35]. Two other single-country studies examined data from Norway and Sweden [22, 30]. Finally, one cross-national case study compared data from Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States [32].

Policy exposures

Seven studies compared the health of social assistance recipients to that of their non-recipient counterparts in Canada, Norway, Sweden, and the United States [22, 24, 25, 28, 30, 35, 38]. Another two examined the health impact of transitions in and out of social assistance recipiency [26, 29]. Four studies measured the health impact of change in the coverage or generosity of social assistance programs in the United States, also known as welfare reform [23, 31, 36, 37]. Welfare reform ended guaranteed federal income support to poor families with children. They also imposed a lifetime limit on the receipt of public assistance and introduced new work-related eligibility requirements [39, 40]. Of the four studies examining the health impact of welfare reform, two looked at the 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA) [23, 31], another looked at the 1994 Florida Family Transition Program (FFTP) [36], and the last looked at the 1996 Connecticut Jobs First (CJF) initiative [37]. The final four studies assessed whether social assistance mitigates the adverse health consequences of unemployment by comparing jobless recipients and non-recipients [27, 32,33,34].

Study designs

Eight studies drew on a descriptive cross-sectional research design [22, 24, 25, 27,28,29,30, 33, 35]. Another five studies employed a descriptive longitudinal research design [26, 29, 32, 34, 38]. The final four studies exploited natural policy experiments to estimate the health impact of welfare reform. Two of these constructed quasi-experiments using difference-in-differences and synthetic control designs to compare change in the health status of policy-exposed and policy-unexposed groups before and after the implementation of PRWORA in the United States [23, 31]. Due to data limitations, neither of these quasi-experimental studies could identify those who were directly affected by welfare reform. Rather, in both cases, the treatment group consisted of those the authors believed were most likely to have been affected; namely, socioeconomically disadvantaged single mothers. The final two papers used policy experiments in Florida and Connecticut to examine the impact of welfare reform [36, 37]. Specifically, the authors compared mortality rates between a treatment group that participated in the reformed social assistance program and a control group that retained their traditional benefits.

Outcomes

Most of the seventeen studies investigated more than one relevant health outcome. More than half of the studies examined the impact of social assistance on one or more dimensions of mental health, including depression, common mental disorders, and adverse psychological symptoms [22, 24,25,26,27,28,29,30, 33,34,35, 38]. Five studies included self-rated health as an outcome [31,32,33, 35, 38]. Three explored health behaviours such as smoking, drinking, and diet [22, 23, 26]. Two studies focused on mortality [36, 37]. Another two looked at chronic conditions and major risk factors for disease such as hypertension and diabetes [35, 38].

Findings

All thirteen descriptive studies found that social assistance was associated with adverse health outcomes. Six cross-sectional studies (quality: weak) comparing the health of social assistance recipients to that of the general population found that recipients reported worse health outcomes than their non-recipient counterparts, even after adjusting for key confounders [22, 24, 25, 28, 30, 35]. In Australia, Canada, Sweden, Norway, and the United States, social assistance recipients reported higher levels of adverse psychological outcomes. The Canadian study also observed an association between social assistance recipiency and higher rates of poor self-rated health (odds ratio (OR) 3.9, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.8–5.3). The Swedish and American studies found worse health behaviours among social assistance recipients, including higher rates of smoking, binge drinking, and harmful dietary habits. In Sweden, for example, the odds of smoking were 4.59 (95% CI 3.56–5.93) times higher among social assistance recipients. Another four descriptive studies spanning three countries (quality: weak or moderate) examined the role of social assistance as a buffer against the adverse health consequences of unemployment [27, 32,33,34]. All four studies failed to identify a protective effect. Rather, they found that those who were unemployed and receiving social assistance reported worse self-rated health, a greater frequency of depressive symptoms, and a higher rate of psychological disorders. Of the remaining descriptive studies, one longitudinal analysis (quality: weak) of a small cohort study in United States reported an association between the receipt of social assistance during young or middle adulthood and adverse health outcomes twenty or thirty years later, including higher rates of poor self-rated health (OR 2.51, p < 0.05, no confidence intervals reported) [38]. The final two descriptive studies (quality: strong) investigated transitions in and out of social assistance in Australia and the United States and found that a movement into social assistance was associated with a higher frequency of depressive symptoms (β = 0.06, p < 0.05), worse mental health scores (β = − 2.45, p < 0.001), and higher rates of binge drinking (OR 2.06, p < 0.05, no confidence intervals reported) [26, 29].

All four experimental or quasi-experimental studies examining the health impact of welfare reform in the United States found that such reforms were associated with adverse health trends. Two studies examined the effects of PRWORA (quality: strong) and found that welfare reform was associated with a 7% increase in the prevalence of poor self-rated health (95% CI 1–12%), an 8.8% increase in the prevalence of smoking (95% CI 6.8–10.8%), and an 8.3% increase in the prevalence of binge drinking (95% CI 14–19%) among the socioeconomically disadvantaged mothers most likely to have been directly affected [23, 31]. Another study (quality: strong) found a 16% (95% CI 14–19%) higher mortality rate among social assistance recipients who participated in the FFTP welfare reform experiment relative to a control group receiving the more traditional and generous set of benefits [36]. A similar investigation of the CJF welfare reform experiment (quality: strong) found higher mortality rates among program participants, though, due in large part to small sample sizes, these estimates did not reach statistical significance [37].

Quality assessment

The results of the methodological quality assessment are presented in Table 3. Seven studies were deemed to be low quality, four studies were moderate quality, and six studies were strong quality. The most common methodological issue was the absence of an experimental or quasi-experimental study design that is capable, at least to some extent, of controlling for unobserved sources of confounding. Only four of the studies were specifically designed to distinguish true policy effects from potential sources of selection bias that render a comparison of recipients and non-recipients problematic. Furthermore, though many of the studies controlled for the most common confounders (e.g. age, gender, marital status, household size, education), few explicitly accounted for the fact that a significant majority of non-recipients are, by definition, ineligible for social assistance (e.g. due to incomes above means-test thresholds) and therefore serve as inappropriate controls.

Discussion

There are several important insights to be gained from our systematic review. Most notably, the results of our review suggest that social assistance recipients tend to exhibit worse health outcomes relative to their non-recipient counterparts. This appears to be the case even after controlling for key demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. This is somewhat puzzling, given that public health theory would predict that these programs are beneficial to health status [1, 9]. The observation that those receiving benefits are faring worse than seemingly comparable non-recipients may reflect that there are, in fact, systematic differences between these populations that are not readily observable using the data upon which these studies rely. There are least two major sources of confounding that could be biasing the results of the reviewed studies. Firstly, individuals who suffer from pre-existing health problems may be selecting into social assistance programs as a means of accessing ancillary benefits that are otherwise out of reach (e.g. health insurance coverage). Secondly, pre-existing health problems may contribute to adverse socioeconomic experiences such as job loss which in turn predict social assistance status. Indeed, there is evidence suggesting that those who suffer from psychological problems have a greater likelihood of experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage and selecting into social assistance [41,42,43]. In a similar vein, findings from the extant literature indicate that problematic risk behaviours such as binge drinking may predict later life socioeconomic hardship, thereby influencing social assistance status [44, 45]. In addition, individuals with unreported material resources such as savings and family wealth may be opting out of, or be ineligible for, these benefits. In all three cases, these residual sources of confounding are likely to bias results towards a negative association between income support and health status.

Alternatively, these findings may reflect the fact that social assistance is increasingly conditional on a range of punitive, work-related obligations that compel entry into precarious employment conditions [46,47,48]. While these measures have been shown to marginally improve employment outcomes among welfare recipients, the terms of their attachment to the labour market tend to be short-lived and produce their own set of adverse socioeconomic consequences, including higher rates of in-work poverty [49]. In fact, recent evidence suggests that these precarious working conditions may pose an equal if not greater risk to health status than the experience of unemployment [50,51,52]. Based on these findings, we might expect social assistance programs that compel marginal labour market attachment to produce negligible or even negative returns to health. Indeed, evidence from the broader literature demonstrates that alternative income maintenance programs which place fewer behavioural requirements on recipients and provide more generous benefit levels than social assistance programs (e.g. unemployment benefits, earned income tax credits, and unconditional cash transfers) have a positive effect on individual health [53,54,55,56,57]. The finding here that social assistance programs are not similarly associated with positive health outcomes may reflect that, unlike other forms of income maintenance, the scope and generosity of existing social assistance programs are insufficient to offset the negative health consequences of the severe socioeconomic disadvantage that renders one eligible for such programs.

In contrast to the puzzling findings reported in descriptive studies, evidence from experimental and quasi-experimental studies of welfare reform in the United States conform to our theoretical expectations. When benefits were reduced and work conditionalities were intensified, there were observable declines in the health status of the socioeconomically disadvantaged groups who tend to be the principal recipients of welfare; namely, poor and low-educated single mothers. Welfare reform is often assumed to promote work and earnings by encouraging reattachment to the labour market. However, the results of existing evaluations suggest that these returns are lukewarm at best [58, 59]. Furthermore, many households affected by welfare reform experienced heightened levels of material hardship [60]. Often, this was because women who were forced to leave welfare ended up in low-paying, insecure jobs [61]. The results of our systematic review lend support to this view by demonstrating that these reforms have had a negative impact on health status, an outcome that is sensitive to material conditions. Thus, while the main finding that social assistance programs do not appear to be succeeding at maintaining the health of the poor frustrates prevailing public health theory, our review provides some evidence suggesting that a reversal of these earlier welfare reforms and a resulting increase in the scope and generosity of social assistance benefits may have a positive effect on the health of socioeconomically disadvantaged populations.

There are several limitations to our analysis. First, we were not able to identify and include studies evaluating policy experiments involving the expansion of social assistance programs. Policy reforms in high-income countries have overwhelmingly involved the retrenchment of established levels of social protection [62,63,64]. Consequently, there are few examples of expansionary policymaking available for evaluation. Second, we restricted our search to peer-reviewed journal articles. Evidence collected in books, reports, and working papers were excluded from the review. We also restricted our search to English-language publications. This may explain why most of the studies included in the review were from English-speaking countries characterized by relatively weak welfare state infrastructures, with a majority being from the United States. Finally, due to heterogeneity across studies both in policy exposures and health outcomes, we were not able to conduct a meta-analysis of their results.

Conclusions

The overall results of our systematic review suggest that evidence on the health impacts of social assistance remains patchy. Rigorous evaluations of these programs are particularly lacking. Few of the studies accounted for systematic differences between social assistance recipients and their non-recipient counterparts. Fewer still adopted the strongest available methods and study designs to evaluate the health effects of policies. We believe there are several principal reasons for the lack of available evidence on the question examined in this review. It may be the case that existing sources of data provide insufficient information for the conduct of rigorous policy evaluations. For example, population-based health surveys tend to provide little if any information on the benefit characteristics of respondents. In addition, while those working in the field of public health may be increasingly familiar with appropriate statistical techniques to evaluate societal-level policy interventions [65,66,67], social assistance programs may not be particularly amenable to the application of such methods. For example, many of the best available methods (e.g. regression discontinuity, difference-in-differences, and interrupted time series designs) require researchers to identify moments of large-scale policy change. In contrast to other areas of public policymaking, such as tobacco or food labelling, social assistance programs are rarely affected by such abrupt punctuations. A notable exception in this regard is welfare reform in the United States, for which there is evidence that we have reviewed here [23, 31, 36, 37]. Finally, institutional barriers associated with the conduct of politically sensitive research may be standing in the way of the generation and dissemination of evidence on social assistance programs. Tackling the structural determinants of health requires large-scale government interventions (e.g. greater income redistribution and labour market regulation) [3]. Such efforts can attract opposition from political actors who oppose such a role for governments [68,69,70,71,72,73,74]. Many epidemiologists and other scientists contributing to the health inequalities literature may, in turn, feel that conducting and disseminating research of this nature is too political or, by virtue of the political opposition they believe it might face, too challenging to undertake [75, 76].

Notwithstanding these important challenges, there is a growing need for evidence on the health effects of social assistance and similar social policies [77]. While governments often identify health equity as an important priority, their choice of interventions have largely relied on behavioural health promotion strategies that fail to account for the role of social policies as necessary levers to reduce health inequalities [78, 79]. Because efforts to eliminate or even reduce health inequalities are unlikely to be successful if they fail to intervene upon their fundamental causes, it is imperative that public health researchers examine these policies and identify the structural interventions that hold the greatest (and the least) promise for reducing health inequalities [80]. The paucity of such evidence is particularly problematic in light of growing evidence that, despite more than a decade of efforts to promote health equity, inequalities in major indicators of population health appear to be widening [81, 82]. These troubling findings may reflect underlying changes in the social and economic architectures of high-income countries, such as the retrenchment of social protection policies – including social assistance programs [49, 62, 83] – and concomitant increases in adverse socioeconomic experiences, such as poverty and unemployment [84, 85]. Taken together, these broader trends highlight a continuing need for solid evidence to marshal in support of interventions that target the fundamental determinants of health.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CJF:

-

Connecticut Jobs First

- FFTP:

-

Florida Family Transition Program

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- PRWORA:

-

Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act

References

Braveman P, Gottlieb L. The social determinants of health: it’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep. 2014;129:19–31.

Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, et al. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2008;372:1661–9.

Solar O, Irwin A. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

World Health Organization. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health: commission on social determinants of health final report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008.

Bahle T, Pfeifer M, Wendt C. Social assistance. In: Castles FG, Leibfried S, Lewis J, et al., editors. The Oxford handbook of the welfare state. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010.

Nelson K. Mechanisms of poverty alleviation: anti-poverty effects of non-means-tested and means-tested benefits in five welfare states. J Eur Soc Policy. 2004;14:371–90.

Kenworthy L. Do social-welfare policies reduce poverty? A cross-national assessment. Soc Forces. 1999;77:1119–39.

Phelan JC, Link BG, Tehranifar P. Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: theory, evidence, and policy implications. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51:S28–40.

Nelson K, Fritzell J. Welfare states and population health: the role of minimum income benefits for mortality. Soc Sci Med. 2014;112:63–71.

Lundberg O, Yngwe MÅ, Stjärne MK, et al. The role of welfare state principles and generosity in social policy programmes for public health: an international comparative study. Lancet. 2008;372:1633–40.

Ruckert A, Labonté R. Health inequities in the age of austerity: the need for social protection policies. Soc Sci Med. 2017;187:306–11.

Morgen S, Acker J, Weigt J. Stretched thin: poor families, welfare work, and welfare reform. Ithaca: Cornell University Press; 2013.

Nelson K. Social assistance and and EU poverty thresholds 1990-2008. Are European welfare systems providing just and fair protection against low income? Eur Sociol Rev. 2013;29:386–401.

Segal H. Finding a better way: a basic income pilot project for Ontario. Toronto: Government of Ontario; 2016.

Black AP, Brimblecombe J, Eyles H, et al. Food subsidy programs and the health and nutritional status of disadvantaged families in high income countries: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:1099.

Pega F, Carter K, Blakely T, et al. In-work tax credits for families and their impact on health status in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;6:CD009963.

Osypuk TL, Joshi P, Geronimo K, et al. Do social and economic policies influence health? A review. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2014;1:149–64.

Renahy E, Mitchell C, Molnar A, et al. Connections between unemployment insurance, poverty and health: a systematic review. Eur J Pub Health. 2018;28:269–75.

Lagarde M, Haines A, Palmer N. The impact of conditional cash transfers on health outcomes and use of health services in low and middle income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;7:CD008137.

Glassman A, Duran D, Fleisher L, et al. Impact of conditional cash transfers on maternal and newborn health. J Health Popul Nutr. 2013;31:S48–66.

National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools. Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies. Hamilton, ON: McMaster University; 2017.

Baigi A, Lindgren E-C, Starrin B, et al. In the shadow of the welfare society ill-health and symptoms, psychological exposure and lifestyle habits among social security recipients: a national survey study. Biopsychosoc Med. 2008;2:15.

Basu S, Rehkopf DH, Siddiqi A, et al. Health behaviors, mental health, and health care utilization among single mothers after welfare reforms in the 1990s. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;183:531–8.

Butterworth P. The prevalence of mental disorders among income support recipients: an important issue for welfare reform. Aust NZ J Pub Health. 2003;27:441–8.

Butterworth P, Burgess PM, Whiteford H. Examining welfare receipt and mental disorders after a decade of reform and prosperity: analysis of the 2007 National Survey of mental health and wellbeing. Aust NZ J Psychiat. 2011;45:54–62.

Dooley D, Prause J. Mental health and welfare transitions: depression and alcohol abuse in AFDC women. Am J Community Psychol. 2002;30:787–813.

Ford E, Clark C, McManus S, et al. Common mental disorders, unemployment and welfare benefits in England. Public Health. 2010;124:675–81.

Jayakody R, Danziger S, Pollack H. Welfare reform, substance use, and mental health. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2000;25:623–52.

Kiely KM, Butterworth P. Social disadvantage and individual vulnerability: a longitudinal investigation of welfare receipt and mental health in Australia. Aust NZ J Psychiat. 2013;47:654–66.

Løyland B, Miaskowski C, Dahl E, et al. Psychological distress and quality of life in long-term social assistance recipients compared to the Norwegian population. Scand J Soc Med. 2011;39:303–11.

Narain K, Bitler M, Ponce N, et al. The impact of welfare reform on the health insurance coverage, utilization and health of low education single mothers. Soc Sci Med. 2017;180:28–35.

Rodriguez E. Keeping the unemployed healthy: the effect of means-tested and entitlement benefits in Britain, Germany, and the United States. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1403–11.

Rodriguez E, Lasch K, Mead JP. The potential role of unemployment benefits in shaping the mental health impact of unemployment. Int J Health Serv. 1997;27:601–23.

Rodriguez E, Frongillo EA, Chandra P. Do social programmes contribute to mental well-being? The long-term impact of unemployment on depression in the United States. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:163–70.

Vozoris NT, Tarasuk VS. The health of Canadians on welfare. Can J Public Health Rev Can Santee Publique. 2004;95:115–20.

Muennig P, Rosen Z, Wilde ET. Welfare programs that target workforce participation may negatively affect mortality. Health Aff. 2013;32:1072–7.

Wilde ET, Rosen Z, Couch K, et al. Impact of welfare reform on mortality: an evaluation of the Connecticut jobs first program, a randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:534–8.

Ensminger ME, Juon H-S. The influence of patterns of welfare receipt during the child-rearing years on later physical and psychological health. Women Health. 2001;32:25–46.

Blank RM. Evaluating welfare reform in the United States. J Econ Lit. 2002;40:1105–66.

Gilbert N. Transformation of the welfare state: the silent surrender of public responsibility. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2002.

Andreeva E, Hanson L, Westerlund H, Theorell T, Brenner MH. Depressive symptoms as a cause and effect of job loss in men and women: evidence in the context of organisational downsizing from the Swedish longitudinal occupational survey of health. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1045.

Callander EJ, Schofield DJ. Psychological distress and the increased risk of falling into poverty: a longitudinal study of Australian adults. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50(10):1547–56.

Kiely KM, Butterworth P. Mental health selection and income support dynamics: multiple spell discrete-time survival analyses of welfare receipt. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68:349–55.

Tucker JS, Orlando M, Ellickson PL. Patterns and correlates of binge drinking trajectories from early adolescence to young adulthood. Health Psychol. 2003;22:79–87.

Viner RM, Taylor B. Adult outcomes of binge drinking in adolescence: findings from a UK national birth cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61:902–7.

Peck J. Workfare states. New York: Guilford Press; 2001.

Deeming C. Rethinking social policy and society. Soc Policy Soc. 2016;15:159–75.

Benach J, Vives A, Amable M, et al. Precarious employment: understanding an emerging social determinant of health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:229–53.

Segal E. The promise of welfare reform: political rhetoric and the reality of poverty in the twenty-first century. New York: Routledge; 2012.

Butterworth P, Leach LS, McManus S, et al. Common mental disorders, unemployment and psychosocial job quality: is a poor job better than no job at all? Psychol Med. 2013;43:1763–72.

Chandola T, Zhang N. Re-employment, job quality, health and allostatic load biomarkers: prospective evidence from the UK household longitudinal study. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47:47–57.

Kim TJ, von dem Knesebeck O. Is an insecure job better for health than having no job at all? A systematic review of studies investigating the health-related risks of both job insecurity and unemployment. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:985.

Evans WN, Garthwaite CL. Giving mom a break: the impact of higher EITC payments on maternal health. Am Econ J. 2014;6(2):258–90.

Pega F, Walter S, Liu SY, et al. Unconditional cash transfers for reducing poverty and vulnerabilities: effect on use of health services and health outcomes in low and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;8:CD011247.

Rehkopf DH, Strully KW, Dow WH. The short-term impacts of earned income tax credit disbursement on health. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(6):1884–94.

O'Campo P, Molnar A, Ng E, et al. Social welfare matters: a realist review of when, how, and why unemployment insurance impacts poverty and health. Soc Sci Med. 2015;132:88–94.

Thornton RL, Glover CM, Cené CW, et al. Evaluating strategies for reducing health disparities by addressing the social determinants of health. Health Aff. 2016;35(8):1416–23.

Eichhorst W, Kaufmann O, Konle-Seidl R. Bringing the jobless into work?: experiences with activation schemes in Europe and the US. New York: Springer; 2008.

Danielson C, Klerman JA. Did welfare reform cause the caseload decline? Soc Serv Rev. 2008;82:703–30.

Danziger S, Heflin CM, Corcoran ME, et al. Does it pay to move from welfare to work? J Policy Anal Manage. 2002;21:671–92.

Corcoran M, Danziger SK, Kalil A, et al. How welfare reform is affecting Women’s work. Annu Rev Sociol. 2000;26:241–69.

Béland D, Daigneault P-M. Welfare reform in Canada: provincial social assistance in comparative perspective. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 2015.

Hacker JS. The great risk shift: the new economic insecurity and the decline of the American dream. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2008.

Betzelt S, Bothfeld S. Activation and labour market reforms in Europe: challenges to social citizenship. New York: Springer; 2011.

Basu S, Meghani A, Siddiqi A. Evaluating the health impact of large-scale public policy changes: classical and novel approaches. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38:351–70.

Craig P, Katikireddi SV, Leyland A, Popham F. Natural experiments: an overview of methods, approaches, and contributions to public health interventions. Annu Rev Public Health. 2018;39:39–56.

Handley MA, Lyles CR, McCullough C, Cattamanchi A. Selecting and improving quasi-experimental designs in effectiveness and implementation research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2018;39:5–25.

Baum FE, Laris P, Fisher M, et al. “Never mind the logic, give me the numbers”: former Australian health ministers’ perspectives on the social determinants of health. Soc Sci Med. 2013;87:138–46.

Braveman P, Egerter S, Williams DR. The social determinants of health: coming of age. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32:381–98.

Embrett MG, Randall GE. Social determinants of health and health equity policy research: exploring the use, misuse, and nonuse of policy analysis theory. Soc Sci Med. 2014;108:147–55.

Frieden TR. A framework for public health action: the health impact pyramid. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(4):590–5.

Goldberg D. In support of a broad model of public health: disparities, social epidemiology, and public health causation. Public Health Ethics. 2009;2(1):70–83.

Pickett K, Wilkinson R. The Spirit level: a case study of the public dissemination of health inequalities research. In: Smith KE, Bambra C, Hill SE, editors. Health inequalities: critical perspectives. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015.

Raphael D, Curry-Stevens A, Bryant T. Barriers to addressing the social determinants of health: insights from the Canadian experience. Health Policy. 2008;88(2–3):222–35.

Douglas M. Beyond ‘health’: why don’t we tackle the cause of health inequalities? In: Smith KE, Bambra C, Hill SE, editors. Health inequalities: critical perspectives. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015.

Muntaner C, Chung H, Murphy K, et al. Barriers to knowledge production, knowledge translation, and urban health policy change: ideological, economic, and political considerations. J Urban Health. 2012;89:915–24.

O’Campo P, Dunn JR. Rethinking social epidemiology: towards a science of change. New York: Springer; 2011.

Bambra C, Smith KE, Garthwaite K, Joyce KE, Hunter DJ. A labour of Sisyphus? Public policy and health inequalities research from the Black and Acheson reports to the Marmot review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65(5):399–406.

Popay J, Whitehead M, Hunter DJ. Injustice is killing people on a large scale—but what is to be done about it? J Public Health. 2010;32(2):148–9.

Whitehead M, Popay J. Swimming upstream? Taking action on the social determinants of health inequalities. Soc Sci Med. 1982;71(7):1234 -1236-1258.

Mackenbach JP, Kulhánová I, Menvielle G, Bopp M, Borrell C, Costa G, et al. Trends in inequalities in premature mortality: a study of 3.2 million deaths in 13 European countries. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(3):207–17.

Bor J, Cohen GH, Galea S. Population health in an era of rising income inequality: USA, 1980-2015. Lancet. 2017;389:1475–90.

Nelson K. Social assistance and EU poverty thresholds 1990-2008. Are European welfare systems providing just and fair protection against low income? Eur Soc Rev. 2013;29(2):386–401.

Schrecker T, Bambra C. How politics makes us sick: neoliberal epidemics. London: Palgrave Macmillan; 2015.

Stuckler D, Basu S. The body economic: why austerity kills. New York: Basic Books; 2013.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

AS is supported by the Canada Research Chairs Program. The study was partially funded by the Ontario Ministry of Community and Social Services. These funding bodies had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its additional files).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: FVS, CR, OSE, AS; Search Strategy: FVS, CR; Identification and Selection of the Literature: FVS, CR; Data Extraction and Quality Assessment: FVS, CR; Narrative Synthesis: FVS, CR, OSE, VH, OSE; Drafting of the Manuscript: FVS, CR, OSE, VH, OSE; Study Supervision: AS. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. Only published reviews were included in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Modified Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies. This file provides a detailed description of the tool used to assess the methodological quality of studies included in the systematic review. (DOCX 75 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Shahidi, F.V., Ramraj, C., Sod-Erdene, O. et al. The impact of social assistance programs on population health: a systematic review of research in high-income countries. BMC Public Health 19, 2 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6337-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6337-1