Abstract

Background

Perinatal mortality is a global health problem, especially in Ethiopia, which has the highest perinatal mortality rate. Studies about perinatal mortality were conducted in Ethiopia, but which factors specifically contribute to the change in perinatal mortality across time is unknown.

Objectives

To assess the trend and multivariate decomposition of perinatal mortality in Ethiopia using EDHS 2005–2016.

Methods

A community-based, cross-sectional study design was used. EDHS 2005–2016 data was used, and weighting has been applied to adjust the difference in the probability of selection. Logit-based multivariate decomposition analysis was used using STATA version 14.1. The best model was selected using the lowest AIC value, and variables were selected with a p-value less than 0.05 at 95% CI.

Result

The trend of perinatal mortality in Ethiopia decreased from 37 per 1000 births in 2005 to 33 per 1000 births in 2016. About 83.3% of the decrease in perinatal mortality in the survey was attributed to the difference in the endowment (composition) of the women. Among the differences in the endowment, the difference in the composition of ANC visits, taking the TT vaccine, urban residence, occupation, secondary education, and birth attendant significantly decreased perinatal mortality in the last 10 years. Among the differences in coefficients, skilled birth attendants significantly decreased perinatal mortality.

Conclusion and recommendation

The perinatal mortality rate in Ethiopia has declined over time. Variables like ANC visits, taking the TT vaccine, urban residence, occupation, secondary education, and skilled birth attendants reduce perinatal mortality. To reduce perinatal mortality more, scaling up maternal and newborn health services has a critical role.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

Perinatal mortality is the death of a fetus starting at 28 weeks of gestation and newborn death up to 7 days after delivery [1, 2]. It is an indicator of the maternal and newborn health service status of a country [3]. Goals are set by the World Health Organization and sustainable development goals to reduce the death of newborns by 2030 to less than 12 per 1000 live births [4, 5]. Ethiopia also shared this plan to achieve the target of reducing neonatal mortality by 12 to 1000 newborns by improving maternal and newborn health services, such as antenatal care utilization, iron supplementation, and skilled delivery [6]. Even though this work has been done, the PM is still a major public health issue and a devastating problem.

Globally, in 2019, about 2.4 million newborn deaths [7] were reported, which is 7.6 times higher than in low-income countries [7, 8]. PM Among the sub-Saharan African countries Ethiopia had the highest perinatal death rate (51.3 per 1000 births) in the years 1997–2019 [9]. Among the most critical times of maternal and newborn death, the first hour and week of delivery contribute to the highest death rate [10]. To measure the reliable figure of mortality during delivery, PM is a more comprehensive indicator than the neonatal mortality indicator [11, 12].

The PM has several consequences. For example, psychological problems (depression, suicidal behavior) reduce work productivity because of grieving and negatively affect couples’ relationships [13, 14]. Other mental disorders like anxiety, stress, and poor partnership are also associated with perinatal loss [15]. Quality of care during birth can save about three million stillbirths and newborns each year [4].

Although interventions such as expanding maternal and child health services are implemented in Ethiopia to reverse the impact of the PM, the PM is still the most challenging public health problem [16]. As different evidence shows, age, delivery place, sex of the child, residence of the woman, antenatal care utilization status, and source of drinking water were the significant factors for PM [17,18,19,20]. Even though PM is a critical problem in Ethiopia, the spatial distribution of the problem, the trend of PM using national-level data (Ethiopian demographic health survey data), and the factors for the trend of PM were not addressed using decomposition analysis. Additionally, most studies about PM were conducted at the health institution level, but there are no adequate studies at the community level about the trend and spatial distribution of PM in Ethiopia. Therefore, the current study aimed to assess the trend and determinants of PM in Ethiopia using further analysis of the Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey (EDHS) 2005–2016 data set using decomposition analysis.

Objectives

To determine the trend of perinatal mortality in Ethiopia using EDHS 2005–2016 data.

To identify the factors attributed to the change in perinatal mortality in Ethiopia using decomposition analysis.

Methods

Data

The EDHS data sets of 2005, 2011, and 2016 were used for the intended analysis using a community-based cross-sectional study design. These demographic surveys used stratified, two-stage cluster sampling techniques. For EDHS-2005, the sampling frame was developed based on the 1994 Ethiopian population and housing census. For EDHS-2011 and EDHS-201, the 2007 Ethiopian population and housing census was used for sampling frame preparation. Geographical areas, or urban and rural areas, were used for stratification purposes. About 21 sampling strata were used for the survey. A total of 540, 624, and 645 enumeration areas with independent and probability-proportional enumeration areas were selected for EDHS-2005, 2011, and 2016, respectively. Then household listing and selection were conducted before the actual data collection procedure, and, on average, 28 households in the enumeration areas were selected using systematic sampling. The detailed selection process was reported in EDHS-2005, EDHS-2011, and EDHS-2016 [21,22,23]. A total of 33,998 sample sizes were used in all surveys (EDHS-2005 = 12035, EDHS-2011 = 10588, EDHS-2016 = 11375) (Fig .1).

Study and source population

The source population was all births from reproductive-age women in Ethiopia. Whereas, the study population was the selected enumeration area in Ethiopia.

Eligibility criteria

All births from the reproductive age women were included in the study whereas those have incomplete data mainly the gestational age, birth dates, and ages at deaths were excluded in the study.

Outcome of interest

Perinatal mortality (Yes, No).

Operational definition

Perinatal mortality is the death of a fetus starting at 28 weeks of gestation and newborn death up to 7 days after delivery (1, 2). The perinatal mortality rate was a dependent variable, including both stillbirths and early neonatal deaths in the five years preceding the survey divided by all births (including stillbirths) that have a pregnancy duration of seven or more months. Stillbirth is defined as pregnancy terminated after seven or more months. Early neonatal death is death within seven days (days 0–6). The outcome variables were coded as “0” for the absence of perinatal mortality and “1” for the presence of perinatal mortality [24].

Data collection procedure

The EDHS data set was used for the current study. This data was accessed by requesting the DHS program website www.measuredhs.com and by explaining the ultimate objective of the current study. The raw data was collected from reproductive-age women who gave birth using a pretested, structured questionnaire. The data was extracted from the birth records of the three consecutive EDHS data sets (2005–2016).

Data management and analysis

Before descriptive and analytical analysis, data were weighted using sampling weight techniques to be more representative. To describe the study subjects and participants, descriptive measures like cross-tabulation were used using STATA version 14. After important predictors are cleaned, coded, and extracted, the EDHS 2005, 2011, and 2016 data sets are merged together for further trend and decomposition analysis.

Trend and decomposition analysis

To assess the trend of perinatal mortality, descriptive analysis was used using selected variables and a combination of EDHS data separately (2005–2011, 2011–2016, and 2005–2016). To determine the trend of perinatal mortality changes, the possible contributing predictors, and the source of the difference in perinatal mortality percentage in Ethiopia from 2005 to 2016, multivariate decomposition analysis was employed. Two important components, such as the composition of the population and the coefficient, were considered to be the contributing factors for the decreasing or increasing pattern of perinatal mortality in Ethiopia since 2005 to 2016. The logit-based multivariate decomposition analysis was used to identify the possible factors for the trend of perinatal mortality in Ethiopia. The logit-based decomposition was using the STATA command mvdcmp [25]. The observed difference in perinatal mortality between the surveys was decomposed into endowment (E) and coefficient (C) components. The endowment (E) means the difference in characteristics, whereas the coefficient (C) means the difference in effects.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants

In all surveys, 16,853 (49.6%) of the participants were aged 20–29 years. Regarding employment status, there was a slight decrease in no work (unemployment) from 2177 (18.1%) in 2005 EDHS to 1457 (12.8%) in 2016 EDHS. From all surveys, about 18,439 (54.2%) participants have had an occupation. Additionally, 4997 (43.9%) of the participants were included in the 2016 EDHS. Furthermore, the majority of participants, 24,551 (72.2%) who were included in the three surveys, had no education, and there was a decline from 9541 (79.3%) in 2005 to 7606 (66.9%) in 2016 (Table 1).

The trend of perinatal mortality rate in Ethiopia

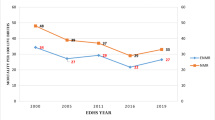

The rate of perinatal mortality in Ethiopia has significantly decreased from a 37 death rate per 1000 births in 2005 to a 33 death rate per 1000 births in 2016 (Fig. 2).

Environmental and health service related characteristics

About 11,154 (92.7%), 9182 (86.7%), and 10,750 (94.5%) of the participants used toilet facilities in 2005, 2011, and 2016, respectively, and there was an increment in toilet facility utilization from 11,154 (92.7%) in 2005 to 10,750 (94.5%) in 2016. Skilled births increased from 5147 (51%) in 2005 to 6563 (62%) in 2011 to 8697 (76.5%) in 2016. The overall ANC utilization in all surveys was 20,635 (61%), and the magnitude increased from 43.3% in 2005 to 61.6% in 2011 to 78.2% in 2016 (Table 2).

Fetal and neonatal related characteristics

The majority of the births 10,836 (90%) in 2005, 9602 (90.7%) in 2011, and 10,186 (89.5%) in 2016 were single. More than half of 23,447 (69%) births in all surveys were 24 months and older. Furthermore, there was a decline in cigarette smoking from 256 (21.3%) in 2005 to 189 (17.8%) in 2011 and 126 (1.1%) in 2016 (Table 3).

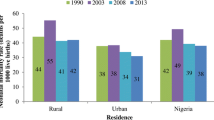

Trends of perinatal mortality rate by women characteristics

The trend of the perinatal mortality rate according to women’s characteristics in Ethiopia from 2005 to 2016 EDHS showed that there was a decline in perinatal mortality in urban residences across all surveys, from 23.3 per 1000 births in 2005 to 16.6 per 1000 births in 2011 and 6.6 per 1000 in 2016. Regarding the regional distribution of the perinatal mortality rate, in the Amhara region, the trend decline across all phases in 2005–2011 (phase-I) declined by 29.9 per 1000 births. In 2011–2016 (phase II), the death rate the death rate declined by 10.6 per 1000 births, and the maximum amount of change was observed in phase III (2005–2016), which was declined by a death rate of 40.5 per 1000 births. Furthermore, the trend of perinatal mortality rate by women aged less than 20 years showed that in phase I (2011–2005), it decreased by 1.6 per 1000 births, in phase III (2016–2011), by 3.4 per 1000 births (Table 4).

Over all decomposition analysis

The overall perinatal mortality in Ethiopia has significantly decreased from 2005 to 2016. As the overall decomposition (2005–2016) analysis showed, the decrease in perinatal mortality in Ethiopia was explained by the endowment of women between each EDHS. Thus, around 83.3% of the perinatal mortality decline was because of the endowment (composition) of the participants, which was statistically significant. The rest was attributed to the change in the coefficients (C) (Table 5).

Detailed decomposition analysis

Among the differences in the endowment, the differences in the endowment, the difference in the composition of ANC visits (B = = -0.00072, 95% CI = -0.0012, -0.0011, p-value = 0.007), taking ≥ 2 TT vaccines (B = -0.0019, 95% CI = -0.0028, -0.0011, p-value = < 0.001), urban residence (B = -0.000499, 95% CI == -0.0033, -0.00061, p-value = 0.004), secondary education (B = 0.0023, 95% CI = 0.000046, 0.0041, p-value = 0.014), and skill birth attendant (B = 0.0069, 95% CI; 0.00068, 0.013, p-value = 0.03) were significantly decrease the perinatal mortality in the last 10 years. Among the differences in coefficients, skilled birth attendant (B = 0.000099, 95% CI: 0.00002, 0.00018, p-value = 0.013) significantly decreased perinatal mortality (Table 6).

Discussion

Perinatal mortality is the most devastating issue in Ethiopia. But the trend and what factors contributed to the increment or decline of perinatal mortality were not studied. Thus, in this study, an attempt has been made to assess the trend and multivariate decomposition of perinatal mortality in Ethiopia.

The trend of perinatal mortality in Ethiopia has decreased over time, from 37 deaths per 1000 births in 2005 to 34 deaths per 1000 births in 2016. This was supported by a systematic review and meta-analysis conducted in Ethiopia [9]. This may be because the Ethiopian government placed an emphasis on maternal and child health services by strengthening the health extension program and exempting the service [26]. The other possible reason might be associated with the fact that the number of skilled birth attendants and the basic service coverage like ANC, post-natal care service, family planning service, and institutional delivery service in Ethiopia increased over time, which enabled the women to get counselling about their pregnancy, their health, fetal condition, birth preparedness, nutrition, and other important messages [27, 28].

Regarding the multivariate decomposition findings, the overall contribution of women’s composition to perinatal mortality in the entire survey (2005–2016) was 83.3%. With an increase in the endowment of urban resident women over the course of the course of the survey, there was a significant decrease in perinatal mortality in Ethiopia. This may be because the expansion of urbanization in Ethiopia may increase the chance of getting maternal and child health services and access to health information for rural women [29, 30].

The increase in the women’s composition of ANC utilization over the survey also had a significant effect on the decrement in perinatal mortality in Ethiopia. This may be because women who visit for ANC service are more likely to give birth and have more children than women who have no history of ANC service [31]. An increase in taking the TT vaccine (taking one or more TT vaccines) over the course of the course of the survey decreased perinatal mortality significantly. The possible reason that might be associated with improving TT vaccination coverage could be to substantially increase the number of newborns protected at birth compared to their counterparts and subsequently reduce the number of newborn deaths [32]. The other possible reason might be that those women who take the TT vaccine are more likely to access other health services like education about pregnancy complications, danger signs, nutrition counselling, and other key messages.

An increase in women who had occupations also had a significant effect on the reduction of perinatal mortality in Ethiopia. This might be because women who have an occupation are more likely to become employed and live in a better socio-economic condition, which leads to better household food security and may reduce maternal malnutrition and its complications [33]. The other possible reason might be that women who have an occupation are more likely to have better knowledge and educational status than those who have no occupation. Thus, better knowledge and educational background are keys to having better information about their health and having good health-seeking behavior for maternal and child health services.

In the current study, an increase in the endowment of women with secondary education also significantly reduced perinatal mortality compared to women with no education. This might be due to women with better educational status, which may increase the chance of having better health information, better nutrition, and better health-seeking behavior than those women who have no education in return, which improves infant survival and healthy maternal conditions [34]. Furthermore, an increase in the endowment (composition) of women who give birth with the assistance of a skilled birth attendant significantly reduces perinatal mortality compared to women who give birth to a non-skilled birth attendant. Regarding the difference in coefficient, giving birth by a skilled birth attendant also significantly contributed to the reduction of perinatal mortality in Ethiopia. The finding was consistent with a systematic and meta-analysis study and a study conducted in the United States of America [35, 36]. This can be justified by the fact that the fact that women who give birth to skilled birth attendants get better delivery care than their counterparts. This can be justified by the fact that the fact that women who give birth to skilled birth attendants get better delivery care than their counterparts. This could reduce the chance of newborn death from sepsis, hypothermia, prolonged labour, and other complications during giving birth. The limitation of the study was that some of the most important variables, such as clinical data, maternal medical and obstetric conditions, and RH incompatibility, were missed in the EDHS data. So further study by considering the above factors is very important.

Conclusion

The trend of perinatal mortality in Ethiopia has declined across time. The change in women’s endowment contributes to more than a third of the perinatal mortality decrease. Among the changes in women’s endowment, variables such as the uptake of the TT vaccine, skilled birth attendants, secondary education, occupation, and ANC utilization contributed to the decline of PM. According to the change in difference coefficients, giving birth by a skilled birth attendant was the most significant predictor of the decline of PM in Ethiopia. To further reduce the PM, scaling up the maternal health service has an abundant advantage. The finding has implications for designing PM reduction strategies and the wise allocation of resources for the interventions.

Data availability

All data are accessed in the article.

Abbreviations

- ANC:

-

Antenatal Care

- DHS:

-

Demographic Health Survey

- EDHS:

-

Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey

- PM:

-

Perinatal Mortality

- TT:

-

Tetanus Toxoid

References

Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and and ICF. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: CSA and ICF.; 2016.

Croft TN, et al. Guide to DHS statistics. Rockville: ICF; 2018.

World Health Organization. Neonatal and perinatal mortality: country, regional and global estimates 2006.

World Health Organization. Every newborn: an action plan to end preventable deaths 2014.

CEPAL N. The 2030 Agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals: An Opportunity for Latin America and the Caribbean 2018.

Federal Democratic Republic Of Ethiopia Ministry Of Health. National Reproductive Health Strategy. 2016 access date occtober 4 /2020]; Available from: URL:https://www.prb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Ethiopia-National-Reproductive-Health-Strategy-2016-2020.pdf

Hug L, et al. A neglected tragedy the global burden of stillbirths: report of the UN inter-agency group for child mortality estimation, 2020. United Nations Children’s Fund; 2020.

Hug L et al. National, regional, and global levels and trends in neonatal mortality between 1990 and 2017, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis (vol 7, pg e710, 2019). 2019. 7(9): pp. E1179-E1179.

Jena BH et al. Magnitude and trend of perinatal mortality and its relationship with inter-pregnancy interval in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. 2020. 20: p. 1–13.

World Health Organization. WHO technical consultation on postpartum and postnatal care. 2010.

Chinkhumba J et al. Maternal and perinatal mortality by place of delivery in sub-Saharan Africa: a meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies 2014. 14(1): pp. 1–9.

Commission NP. Nigeria demographic and health survey 2013. National Population Commission, ICF International; 2013.

Fernández-Sola C, et al. Impact of perinatal death on the social and family context of the parents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(10):3421.

Gausia K, et al. Psychological and social consequences among mothers suffering from perinatal loss: perspective from a low income country. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):451.

Hutti MH, et al. Grief intensity, psychological well-being, and the intimate partner relationship in the subsequent pregnancy after a perinatal loss. J Obstetric Gynecologic Neonatal Nurs. 2015;44(1):42–50.

Federal MaCHD. and Ministry of Health. National Strategy for Newborn and Child Survival in Ethiopia. 2015 access date october 3/2020]; https://www.healthynewbornnetwork.org/hnn-content/uploads/nationalstrategy-for-newborn-and-child-survival-in-ethiopia-201516-201920.pdf

Ezeh OK, et al. Community-and proximate-level factors associated with perinatal mortality in Nigeria: evidence from a nationwide household survey. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):811.

Benjamin A, Sengupta P, Singh S. Perinatal mortality and its risk factors in Ludhiana: a population-based prospective cohort study. Health Population: Perspect Issues. 2009;32(1):12–20.

Al Kibria GM et al. Determinants of early neonatal mortality in Afghanistan: an analysis of the Demographic and Health Survey 2015 Globalization and health, 2018;14(1): 47.

Woldeamanuel BT, Gelebo KK. Statistical analysis of socioeconomic and demographic correlates of perinatal mortality in Tigray Region, Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1301.

Csa IJE, health survey, Ethiopia, Calverton M. USA, Central statistical agency (CSA)[Ethiopia] and ICF 2016. 1.

CSA, I.J.A.A., Ethiopia M, Calverton USA. Central Statistical Agency, and I. International, Ethiopia demographic and health survey 2011 2012. 430.

Demographic EJE, Calverton. Health Survey 2005: Addis Ababa 2006.

Girma D et al. Individual and community-level factors of perinatal mortality in the high mortality regions of Ethiopia: a multilevel mixed-effect analysis 2022. 22(1): p. 247.

Powers DA, Yoshioka H, Yun M-SJTSJ. Mvdcmp: Multivar Decompos Nonlinear Response Models. 2011;11(4):556–76.

Medhanyie A et al. The role of health extension workers in improving utilization of maternal health services in rural areas in Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. 2012. 12(1): p. 1–9.

Regassa NJ. A.h.s., Antenatal and postnatal care service utilization in southern Ethiopia: a population-based study. 2011. 11(3).

Mrisho M, et al. The use of antenatal and postnatal care: perspectives and experiences of women and health care providers. Rural South Tanzan. 2009;9:1–12.

Tesfaunegn E, Cooperation. Urban and Peri-urban development dynamics in EthiopiaSwiss Agency for Development and CooperationUrban and Periurban development dynamics in Ethiopia 2017.

Harpham T. J.S.s. and medicine, Urbanization and mental health in developing countries: a research role for social scientists, public health professionals and social psychiatrists 1994. 39(2): pp. 233–245.

Shiferaw K et al. The effect of antenatal care on perinatal outcomes in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. 2021. 16(1): p. e0245003.

Singh A et al. Maternal tetanus toxoid vaccination and neonatal mortality in rural north India 2012. 7(11): p. e48891.

Akinyemi JO, Solanke BL. O.J.A.o.g.h. Odimegwu, maternal employment and child survival during the era of sustainable development goals. Insights Proportional Hazards Modelling Nigeria Birth History data. 2018;84(1):15.

Organization WH. Maternal education and child health in the Western Pacific Region 1995.

Yakoob MY et al. The effect of providing skilled birth attendance and emergency obstetric care in preventing stillbirths. 2011. 11: p. 1–8.

Singh K et al. A regional multilevel analysis: can skilled birth attendants uniformly decrease neonatal mortality? 2014. 18: p. 242–9.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to give thanks to DHS international for giving permission to utilize the data.

Funding

No funding source.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: MCA, SD, WN, HSH. Data curation: SD, AS, TM, YT. Formal analysis: MC, AK, AS, DK. Investigation: MCA, TK, TM, YT. Methodology: MCA, DK, WN, GA. Software: MCA, YT, AS, SZ, HSH. Supervision: MCA, HSH. Visualization: SZ, SD, TM, TK, YT, WN, DK, GA. Writing – original draft: MCA, SD, SZ, GA.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval from individual participants was not obtained because of secondary data. Rather, permission was obtained from DHS International to access the data.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Agimas, M.C., Kefale, D., Tesfie, T.K. et al. Trend, and multivariate decomposition of perinatal mortality in Ethiopia using further analysis of EDHS 2005–2016. BMC Pediatr 24, 523 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-024-04998-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-024-04998-3