Abstract

Background

In a cohort of hospitalized children with congenital heart disease (CHD), a new digital pediatric malnutrition screening tool as a mobile application was validated, and its effectiveness and clinical value were determined as a prospective study.

Methods and results

Children with CHD (n = 1125) were screened for malnutrition risk. The incidence of risk and the differences among various age groups and types of CHD were characterized. The optimal threshold for the tool to determine if there is a risk of malnutrition is score 2, while the Youden index was 79.1%, and the sensitivity and specificity were 91.2% and 87.9%, respectively. Based on such criterion, 351 children were at risk of malnutrition accounting for 31.20% of the total. Compared with the non-malnutritional risk group, the median age for the group at risk for malnutrition was younger (8.641 months [4.8, 23.1] vs. 31.589 months [12.4, 54.3], P < 0.01), and the length of stay was longer (12.000 [8.0, 17.0] vs. (8.420 [5.0, 12.0], P < 0.01]. There were significant differences in malnutrition risk among different age groups (χ2 = 144.933, P < 0.01), and children under one year of age exhibited the highest risk for malnutrition and more extended hospital stay (H = 78.085, P < 0.01). The risk of malnutrition among children with cyanotic CHD was higher than in those with non-cyanotic CHD (χ2 = 104.384, P < 0.01).

Conclusions

The new digital pediatric malnutrition screening tool showed high sensitivity and specificity in children with CHD. The tool indicated that the malnutrition risk for young children and children with cyanotic or Bethesda moderate and complex CHD was higher, and the hospitalization time was longer than in the non-risk group. The tool provides a rational approach to targeted nutrition intervention and support and may improve clinical outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is one of the most common developmental abnormalities in children, with 4–10 cases per 1000 live births worldwide [1]. In China, CHD is the most common congenital abnormaly [2, 3]. Although most children with CHD exhibit normal weight at birth, due to abnormal hemodynamics, an increase in cardiopulmonary oxygen consumption, a diminution in energy intake, an elevation in sympathetic nerve activity, and feeding difficulties, these children lose weight secondary, in part, to a lack of specific nutrients or insufficient calorie intake [4,5,6]. Previous studies revealed that 15–41% of children with CHD developed malnutrition and growth disorders [1].

In hospitalized children, malnutrition precipitated by disease constitutes one of the principal reasons for prolonging the course of disease and increasing hospitalization time [7, 8]. Malnutrition affects growth and development, clinical prognosis, postoperative recovery, and length of hospital stay [6, 9]. It also can decrease bodily functions, and increase disease-related complications and mortality [10, 11]. For children with CHD, good nutritional status during the perioperative period is important, and therefore, nutritional risk screening and assessment should be completed in a timely manner. Appropriate intervention can accelerate the treatment and rehabilitation of the disease and shorten the recovery period and hospitalization days, reduce complications, lower costs, and improve clinical outcomes [8, 11, 12].

The nutritional risk screening tools presently used include the nutrition status and growth risk screening tool (STRONGkids), pediatric malnutrition assessment and screening tool (STAMP), Yorkhill pediatric malnutrition score (PYMS), digital measurement malnutrition risk screening tool (PediSmart), and the pediatric nutrition screening tool (PNST) [7, 13, 14]. However, the reliability and performance of these tools are inconsistent [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. In China and elsewhere, there is still no universal pediatric nutritional-risk screening tool. The application of nutritional s tatus screening tools in children with CHD thus warrants further study.

Herein, we tested an optimized pediatric malnutrition-risk screening tool in hospitalized children with CHD. By investigating the detection rate for nutritional risk and analyzing the correlation between nutritional risk and clinical results, we evaluated the tool’s feasibility, its effectiveness, and its clinical value.

Methods

Subjects

Children hospitalized in Xinhua Hospital affiliated to the School of Medicine of Shanghai Jiao Tong University between May 2018 and November 2021 were selected prospectively. Inclusion criteria were (1) age 1 month—18 years corrected gestational age; (2) diagnosis of congenital heart disease; (3) admitted to the Pediatric Heart Center of the hospital; (4) a hospital stay length > 3 days; and (5) screening for malnutrition risk within 48 h after admission. The protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Xinhua Hospital affiliated to the School of Medicine of Shanghai Jiao Tong University (China; Approval No. XHEC-D-2020–071).

Clinical data collection and anthropometric measurements

Patient sex, age, primary diagnosis, weight, height (at over two years of age) and length (at under two years of age), length of hospital stay, and nutrition intervention were recorded upon hospital admission and at discharge by the nursing staff. Body weight and length were measured with an infant scale with an attached infantometer (Seca 376 electronic baby scale; Seca Ltd, Hamburg, Germany) in children < 2 years of age and with an electronic scale and a stadiometer (RGZ-120; Shanghai Dongfang scales Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China) in children ≥ 2 years of age. Height was accurate to 0.1 cm, and weight was accurate to 0.1 kg. BMI was calculated as body weight (kg)/[length or height (m)]2. Z-scores were derived based on the WHO Child Growth standard charts [23].

Screening of malnutrition risk

The screening tool was consolidated into a mobile application in this study, which could be downloaded in the app store (China) as “Er Ke Ying Yang Shai Cha(Pediatric Nutritional Risk Screening)”. The nurses involved in the study were installed with this app in their phones, and the accounts were managed by the administrator account. The pediatric malnutrition risk screening part was developed by our research team [22], which consisted of three elements: disease risk, dietary intake, and anthropometric indicator. The score for disease risk was determined according to the primary diagnosis based on the ICD-10, while the anthropometric indicator Z refers to weight for height values and was automatically calculated in the app (see Table 1 for details). Nurses were in charge of the screening (input the basic information of the three elements) and trained prior to the project. The same screening questions were used at admission and discharge. The risk results were automatically sent to registered dietitians and physicians via the application for further assessment and treatment with caloric intake evaluation and other variables.

Criteria for malnutrition

For assessment of pediatric malnutrition risk, the WHO Z-score method is often used as a reference [24, 25]. Height for age Z value (HFA), weight for age Z value (WFA), and weight for height Z value (WFH) are suitable for children 0–5 years of age; and the age-specific body-mass index Z value (BMIZ) is suitable for individuals 5–18 years of age. We designated WFA or BMI Z < − 2 as low weight, HFA < − 2 as growth retardation, WFH < − 2 as stunting, WFA > 2 or BMIZ > 1 as overweight, and WFA > 3 or BMIZ > 2 as obesity. The children found to be low weight, growth retardation, stunting or overweight were rated as malnutrition, and Z < − 3 or Z > 3 denoted severe malnutrition [26]. In addition to the WHO standard, the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) criteria for malnutrition in children was used as a reference standard for comparison [27].

Statistical treatment

The SPSS 21.0 software package was used for statistical analysis. R version 3.5.3 software was used for receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve drawing. Non-normally distributed data are expressed as median (M) and interquartile interval (P25, P75). The Mann–Whitney U test was used for two groups of independent samples, and the Kruskal–Wallis H test for multiple independent samples. Counting data are expressed as rate (%) and were analyzed with the Chi-squared test. The specificity, sensitivity, and cut-off value were calculated and judged using ROC curves. The Youden index and kappa value were used to determine the consistency of screening results. Binary logit regression analysis was used to investigate which characteristics were correlated. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

General information

The study cohort included 1125 children with congenital heart disease. There were 575 boys (51.11%) with a median age of 21.40 (6.80, 45.01) months. The median age for the 550 girls (48.89%) was 25.12 (7.65, 50.84) months. The median Z scores for WFH, WFA, HFA, and BMI did not differ significantly between boys and girls. Consequently, gender was not considered in the analysis.

According to WHO standards, there were 272 cases of malnutrition at admission, with an incidence rate of 24.18%. Of these, 85 cases were graded as severe malnutrition, accounting for 31.25%. The incidence rates of underweight, retardation, and stunting were 142 cases (12.62%), 146 cases (12.98%), and 99 cases (8.80%), respectively. Forty-eight cases were overweight and 13 were obese (see Table 2).

There were 193 cases (17.16%) of cyanosis and 932 cases (82.84%) without cyanosis. Based on Bethesda classification of congenital heart disease, there were 535 (47.56%) simple cases, 390 (34.67%) moderate cases, and 200 (17.78%) cases with high severity.

Tool validation and results

Validation of cut-off value for screening score

The ROC curve is used to judge the ability of risk identification and the closer the AUC (area under curve) is to 1, the better the identification effect. In our study, the AUC between malnutrition risk and non-risk was 0.924 (P < 0.01, 95% CI = 0.907–0.941) (Fig. 1). A critical value of 2 provided the best cut-off point (Youden index = 79.1%), with a sensitivity of 91.2% and a specificity of 87.9% (Table 3); the value was 0–1 for the non-malnutrition risk group and 2–5 for the malnutrition-risk group.

Screening results

When we assigned two points as the boundary, there were 351 cases in the risk group (accounting for 31.20% of the total) and 774 cases in the non-risk group (68.80%). Of these, 454 cases (40.36%) scored 0, 320 cases (28.44%) scored 1, 191 (16.98%) scored 2, 128 (11.38%) scored 3, and 33 (2.93%) scored 4. Two cases exhibited dietary-intake risk and 189 cases manifested disease risk.

Comparison of different reference standards

We adopted the WHO and ASPEN criteria for the screening results. According to the WHO standard, 272 cases were designated with malnutrition and the incidence rate was 24.18%; with 213 cases according to the ASPEN standard (18.93%). The values of sensitivity, specificity, positive-predictive value (PPV), and negative-predictive value (NPV) of each reference are shown in Table 5. The kappa test showed that the screening results were highly consistent with the WHO standard (κ = 0.720) and maintained a degree of consistency with the ASPEN standard (κ = 0.313) (Table 4). The comparison of ROC is shown in Fig. 1. None of the 61 WHO-standard overweight and obese cases were detected by the screening with nutritional risk.

Discharge data

Screening data at discharge were available for 828 of the 1125 children (73.6%). Within this group, 82.00% of the children gained no weight or lost weight, and 18.00% gained weight. Forty-three patients (5.20%) had a weight loss of more than 5% during their admission. Children in the non-risk group had a significantly greater increase in weight between admission and discharge compared with the risk group (p < 0.001).

Comparison of different nutritional risk groups

We found that the median age of the risk group was significantly less than that of the non-risk group (8.641 months [4.8, 23.1] vs. 31.589 months [12.4, 54.3], P < 0.01), and that the median length of hospital stay for the risk group (12.000 [8.0, 17.0]) was significantly longer than for the non-risk group (8.420 [5.0, 12.0], P < 0.01). The values for WFH Z, WFA Z, HFA Z, and BMI Z in the risk group were lower than those for the non-risk group (Table 5).

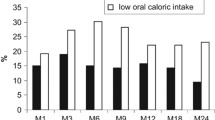

Comparison of different age groups

There were significant differences in malnutrition risk among different age groups (χ2 = ? 144.933, P < 0.01). Children under one year of age exhibited the highest risk of malnutrition and longer hospitalization time (H = 78.085, P < 0.01). Children over five years had the shortest hospitalization time (Table 6).

Comparison of different types of congenital heart disease

CHD is divided into cyanotic (associated with several anatomic abnormalities such as transposition of the great vessels, tetralogy of Fallot, etc.) and non-cyanotic. The non-cyanotic type can be subdivided into obstructive malformations (pulmonary artery stenosis, aortic coarctation, right heart position, etc.) and left-to-right shunt malformation (patent ductus arteriosus, ventricular septal defect, atrial septal defect, etc.) [28]. The risk of malnutrition was higher in those with cyanotic heart disease than in those with non-cyanotic heart disease (χ2 = 97.286, p < 0.01). Based on Bethesda classification, the cases were also divided into simple, moderate and complex groups. The results show significantly lower malnutrition risk in simple group, while higher risks in moderate and complex groups (χ2 = 400.694, p < 0.01) (Table 7).

Influencing factor analysis of malnutrition at discharge

A binary logit regression analysis was performed for CHD children at discharge with possible influencing factors including gender, age, length of stay, disease risk and diet as independent variables and WHO criteria for malnutrition as dependent variables. As shown in Table 8, LOS and disease risk had a significant positive effect on malnutrition; age of month had a significant negative effect on malnutrition; but gender and diet did not have an effect on malnutrition.

Discussion

Children with CHD are often at greater risk for malnutrition and growth defects, as augmented sympathetic activity, elevated respiratory function, and congestive heart failure increase metabolic demand [5]. A higher incidence of gastrointestinal structural abnormalities, gastroesophageal reflux, and food intolerance also occur. For example, the rate of neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) in children with CHD is 10–100 times higher than that in normal children. Furthermore, preoperative fasting may lead to undernutrition, which increases the risk for malnutrition [1].

The European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Hepatology called for establishing a Nutrition Support Team (NST) that was focused on scientific and effective nutrition management of hospitalized children and a reduction in the prevalence of malnutrition [29]. Perioperative nutritional management is the key to improving the clinical prognosis of children with CHD. According to an expert consensus on nutritional support for children with CHD, the nutritional-screening evaluation suggests that screening be conducted within 24 h after admission, 3–7 days after surgery and before discharge, and once per week if the hospitalization time is over two weeks [30]. As a first step, nutritional risk screening requires convenient and practical tools. An ideal malnutrition-risk screening tool should be sensitive, accurate, and be easy to apply [7].

The earliest study of nutritional status of CHD children in China found incidence rates for acute and chronic malnutrition of 48.4% and 37.5%, respectively [31]. In our analysis, the incidence of malnutrition in children with CHD was 31.20%, which was similar to the data from several small-sample studies that used the Z-score method (30.30%–57.14%) [32, 33]. Other reports also validated the Canadian Infant Feeding & Nutrition Checklist for Congenital Heart Disease (IFNC: CHD) assessment tool [9]. However, none of the above tools were verified by multi-center and large-sample investigations with ideal sensitivity and specificity.

The factors that promote malnutrition in children with CHD are many and can include feeding and maternal behavior. In the present study, we used a modified pediatric malnutrition risk tool to screen the nutritional risk for children with CHD in China. Our data suggested that the risk of malnutrition in young children with cyanotic CHD was higher and the hospitalization time longer than in their counterparts. A limitation of this study is that the screening tool was employed by different nurses, possibly influencing the results whereas we provided a training session to all participants at the beginning of the project. Also, for the dietary intake part of the tool, different scores are assigned as “Normal, no obvious change”, “Less than or equal to 50% less than usual in the previous month”, and “Over the previous month, eating decreased by more than 50% compared with normal” from 0,1 to 2 respectively, while only two cases exhibited dietary intake risk. Such result might show that the intake measure does not strengthen the tool that it did not really depict the feeding situations of the children. For further studies, it is suggested that the feeding status, growth rate, CHD type and complications, postoperative complications, postoperative mechanical ventilation time, medication use, differentiation of corrected vs. non-corrected CHD in older children, and readmission rate be incorporated into the tool for analysis and further validation. A decrease in weight for age during the first months after surgery for congenital heart problems is strongly related to late mortality in children [34]. Hence, timely screening with a convenient tool such as the one in this study, nutritional support, and follow-up post-surgery should be conducted to improve clinical outcome to optimize the health of CHD children.

Conclusion

The new digital pediatric malnutrition screening tool showed high sensitivity and specificity in children with CHD. It is convenient and easy to apply. The tool indicated that the malnutrition risk for young children and children with cyanotic or Bethesda moderate and complex CHD was higher, and the hospitalization time was longer than in the non-risk group. It also provides a rational approach to targeted nutrition intervention and support and may improve clinical outcomes.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Martini S, Beghetti I, Annunziata M, Aceti A, Galletti S, Ragni L, Donti A, Corvaglia L. Enteral nutrition in term infants with congenital heart disease: Knowledge gaps and future directions to improve clinical practice. Nutrients. 2021;13:932. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030932.

Expert Committee on Congenital Heart Disease of the Pediatricians Branch of the Chinese Medical Association, Cardiovascular Group of the Pediatric Branch of the Chinese Medical Association, Editorial Committee of the Chinese Journal of Pediatrics. Expert consensus on the interventional treatment of common congenital heart diseases in children. Chin J Pediatr. 2015;53:17–24. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1310.2015.01.004.

Zhang MJ, Wang LP, Huang R, Sun CR, Xu ZM. Risk factors of malnutrition in Chinese children with congenital heart defect. BMC Pediatr. 2020;20:213. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.2.18951/v2.

Nydegger A, Bines JE. Energy metabolism in infants with congenital heart disease. Nutrition. 2006;22:697–704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2006.03.010.

Forchielli ML, McColl R, Walker WA, Lo C. Children with congenital heart disease: A nutrition challenge. Nutr Rev. 2009;52:348–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.1994.tb01359.x.

Daymont C, Neal A, Prosnitz A, Cohen MS. Growth in children with congenital heart disease. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e236–42. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-1157.

Dokal K, Asmar N, Shergill-Bonner R, Mutalib M. Nutrition evaluation screening tool: An easy to use screening tool for hospitalised children. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2021;24:90–9. https://doi.org/10.5223/pghn.2021.24.1.90.

Kruizenga H, van Keeken S, Weijs P, Bastiaanse L, Beijer S, Huisman-de Waal G, et al. Undernutrition screening survey in 564,063 patients: patients with a positive undernutrition screening score stay in hospital 1.4 d longer. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103:1026–32. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.115.126615.

St. Pierre A, Khattra P, Johnson M, Cender L, Manzano S, Holsti L. Content validation of the infant malnutrition and feeding checklist for congenital heart disease: A tool to identify risk of malnutrition and feeding difficulties in infants with congenital heart disease. J Pediatr Nurs. 2010;25:367–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2009.04.009.

Santos CAd, Rosa CdOB, Franceschini SdCC, Firmino HH, Ribeiro AQ. Nutrition risk assessed by STRONGkids predicts longer hospital stay in a pediatric cohort: A survival analysis. Nutr Clin Pract. 2020;36:233–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/ncp.10589.

Sheng JY, Mao XM, Lu LN, Niu Y, Tang QY, CAai W. Application of modified pediatric malnutrition risk screening tool in hospitalized children. Chin J Pract Pediatr. 2018;33:281–5. https://doi.org/10.19538/j.ek2018040610.

Zhu MM, Chen F, Xu J, Yuan LH, Zhang Y, Ji X, Qiu JC. The role of Chinese clinical pharmacists in parenteral nutrition for children using the Screening Tool Risk on Nutrititional Status and Growth (STRONGkids). Int J Clin Pharm. 2020;43:518–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-020-01156-4.

Hulst JM, Zwart H, Hop WC, Joosten KFM. Dutch national survey to test the STRONGkids nutritional risk screening tool in hospitalized children. Clin Nutr. 2010;29:106–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2009.07.006.

Carter LE, Shoyele G, Southon S, Farmer A, Persad R, Mazurak VC, Brunet Wood MK. Screening for pediatric malnutrition at hospital admission: Which screening tool is best? Nutr Clin Pract. 2020;35:951–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/ncp.10367.

Wonoputri N, Djais JTB, Rosalina I. Validity of nutritional screening tools for hospitalized children. J Nutr Metab. 2014;2014:143649. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/143649.

Lestari NE, Nurhaeni N, Wanda D. The pediatric yorkhill malnutrition score is a reliable malnutrition screening tool. Compr Child Adolesc Nurs. 2017;40:62–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694193.2017.1386972.

Teixeira AF, Viana KDAL. Nutritional screening in hospitalized pediatric patients: A systematic review. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2016;92:343–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2015.08.011.

Moeeni V, Walls T, Day AS. Nutritional status and nutrition risk screening in hospitalized children in New Zealand. Acta Paediatr. 2013;102:e419–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.12299.

da Cruz Gouveia MA, Tassitano RM, da Silva GAP. STRONGkids: Predictive validation in Brazilian children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;67:e51–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/mpg.0000000000002029.

Pérez-Solís D, Larrea-Tamayo E, Menéndez-Arias C, Molinos-Norniella C, Bueno-Pardo S, Jiménez-Treviño S, Bousoño-Garcia C, Díaz-Martín JJ. Assessment of two nutritional screening tools in hospitalized children. Nutrients. 2020;12:1221. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12051221.

Santos CAd, Rosa CdOB, Franceschini SdCC, Castro JdS, Costa IBM, Firmino HH, Ribeiro AQ. StrongKids for pediatric nutritional risk screening in Brazil: A validation study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2020;74:1299–305. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-020-0644-1.

Beser OF, Cokugras FC, Erkan T, Kutlu T, Yagci RV, Ertem D, et al. Evaluation of malnutrition development risk in hospitalized children. Nutrition. 2018;48:40–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2017.10.020.

WHO. Child growth standard. https://www.who.int/toolkits/child-growth-standards/standards.

Rub G, Marderfeld L, Shamir R. Nutritional screening tools for malnutrition in pediatrics. In: Preedy VR, Patel VB, editors. Handbook of famine, starvation, and nutrient deprivation: From biology to policy. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019. p. 665–81.

Klanjsek P, Pajnkihar M, MarcunVarda N, PovalejBrzan P. Screening and assessment tools for early detection of malnutrition in hospitalised children: a systematic review of validation studies. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e025444. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025444.

Sermet-Gaudelus I, Poisson-Salomon A-S, Colomb V, Brusset M-C, Mosser F, Berrier F, Ricour C. Simple pediatric nutritional risk score to identify children at risk of malnutrition. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:64–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/72.1.64.

Becker P, Carney LN, Corkins MR, Monczka J, Smith E, Smith SE, Spear BA, White JV. Consensus statement of the academy of nutrition and dietetics/American society for parenteral and enteral nutrition. Nutr Clin Pract. 2014;30:147–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/0884533614557642.

Cai W, Zhang WP, Wei GH. Pediatric surgery. Beijing: People’s Health Publishing House; 2014.

Kondrup J. ESPEN guidelines for nutrition screening 2002. Clin Nutr. 2003;22:415–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0261-5614(03)00098-0.

Cardiothoracic Surgery Group of Pediatric Surgery Branch of Chinese Medical Association, Chinese Medical Association Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition Branch Pediatrics Group. Expert consensus on nutritional support for children with congenital heart disease. Chin J Pediatr Surg. 2016;37:3–8. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-3006.2016.01.002.

Yu LH, Cai W. Nutritional evaluation of 512 cases of children with congenital heart disease. Chin J Pract Pediatr. 2003;18:237–8. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1005-2224.2003.04.021.

Xie S, Yin XR, Zhao Y, Lu XY. Preoperative nutritional status and influencing factors of children with congenital heart disease. Food Nutr China. 2020;26:86–8. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1006-9577.2020.03.020.

Qi JR, Mo XM, Li R, Li XN. STRONGkids for congenital heart disease perioperative nutritional risk screening. Chin J Clin Nutr. 2014;22:38–42. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.1674-635X.2014.01.008.

Eskedal LT, Hagemo PS, Seem E, Eskild A, Cvancarova M, Seiler S, Thaulow E. Impaired weight gain predicts risk of late death after surgery for congenital heart defects. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:495–501. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2007.126219.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by every member in the nutrition support team of Xinhua Hospital, as well as the academic and practical institutions who explore and develop the project with us. We also would like to express our gratitude to the editor and reviewers for helping us improve our manuscript.

Funding

Project of cultivation for multidisciplinary treatment in critical illness by Shanghai health commission (Z155080000004); Shanghai Natural Science Foundation (22ZR1441100); Clinical Research Plan of SHDC (SHDC2020CR2010A); Shanghai “Science and technology innovation action plan” (22Y31900600).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yajie Zhang and Lina Lu equally contributed to the conception and design of the research; Weihui Yan contributed to the design of the research; Yajie Zhang and Lina Lu contributed to the acquisition and analysis of the data; Ling Yang, Qun Yu, Jinye Sheng and Xiaomeng Mao contributed to the acquisition and input of the data; Yajie Zhang drafted the manuscript; Yi Feng and Qingya Tang critically revised the manuscript; Wei Cai and Ying Wang equally contributed to the conception, design of the research and critically revised the manuscript. All authors drafted the manuscript, critically revised the manuscript, agree to be fully accountable for ensuring the integrity and accuracy of the work, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Xinhua Hospital affiliated to the School of Medicine of Shanghai Jiao Tong University (China; Approval No. XHEC-D-2020–071). Informed Consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s) and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Lu, L., Yang, L. et al. Evaluation of a new digital pediatric malnutrition risk screening tool for hospitalized children with congenital heart disease. BMC Pediatr 23, 126 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-023-03899-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-023-03899-1