Abstract

Background

Mental health problems often arise in childhood and adolescence and can have detrimental effects on people’s quality of life (QoL). Therefore, it is of great importance for clinicians, policymakers and researchers to adequately measure QoL in children. With this review, we aim to provide an overview of existing generic measures of QoL suitable for economic evaluations in children with mental health problems.

Methods

First, we undertook a meta-review of QoL instruments in which we identified all relevant instruments. Next, we performed a systematic review of the psychometric properties of the identified instruments. Lastly, the results were summarized in a decision tree.

Results

This review provides an overview of these 22 generic instruments available to measure QoL in children with psychosocial and or mental health problems and their psychometric properties. A systematic search into the psychometric quality of these instruments found 195 suitable papers, of which 30 assessed psychometric quality in child and adolescent mental health.

Conclusions

We found that none of the instruments was perfect for use in economic evaluation of child and adolescent mental health care as all instruments had disadvantages, ranging from lack of psychometric research, no proxy version, not being suitable for young children, no age-specific value set for children under 18, to insufficient focus on relevant domains (e.g. social and emotional domains).

Similar content being viewed by others

Highlights

-

1.

Mental health problems have detrimental effects on people’s quality of life (QoL).

-

2.

None of the currently available instruments to measure QoL was perfect for use in economic evaluation of child mental health care

-

3.

All instruments had disadvantages, ranging from lack of psychometric research, no proxy version, not being suitable for young children, no age-specific value set, to insufficient focus on relevant domains.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has categorized mental health problems among the most disabling in the world [1]. Furthermore, the incidence of mental health problems has been increasing [2]. Around 20% of the working age population in Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries is currently suffering from a mental disorder, and over the life course 40% is affected [2]. Many mental health disorders have their origin in childhood and adolescence [3]. Serious and common long-term effects such as substance abuse [4], poor work [5] and academic performance [6], problems with peer and romantic relations [7], and development of other psychiatric disorders do occur [8]. Consequently, mental health problems have detrimental effects on people’s quality of life (QoL) [9,10,11].

The WHO defines QoL as “individuals’ perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns” [12]. At any given time, social, psychological, and biological factors determine a persons’ mental health, and this can affect a persons’ QoL. The definition of QoL is broad and related to several aspects, including physical health, psychological state, level of independence, social relationships, personal beliefs, and their relationship to salient features of their environment [13]. Thus, a measure for QoL should capture multiple domains and cannot be considered a single concept.

Assessing QoL is important, not only in clinical practice and research, but also in the field of health economics. The latter obviously prompted by an increased interest in the societal impact of interventions and the growing attention for economic evaluations in child and adolescent mental health care, given the chance of life-long reduction of cost associated with mental health problems in children. Policy makers increasingly base their decisions on outcomes of economic evaluations [14]. Therefore, a standardized method for performing economic evaluations in pediatric mental health care is of great significance. However, methods and instruments used in economic evaluations have traditionally been developed for the somatic (health) care, and mostly for an adult population. Moreover, very different aspects of QoL are considered relevant in this field, although the term used (i.e., QoL) is the same. As a result, performing and interpreting standardized and reliable economic evaluations in this sector remains challenging.

Problems in assessing quality of life in children with psychiatric disorders

A major concern in measuring QoL in children with mental health issues is that many instruments available to measure QoL in children have been derived from adult versions [15]. Factors that might affect an appropriate understanding of instruments measuring QoL are language development, cognitive development, and type of disorder [16, 17]. Often, it is assumed that measuring QoL in children below the age of eight is not feasible and reliable. Proxy versions of instruments can be used in this group, but these have limitations as well. Where possible, it is recommended to let an individual report on their own QoL, perhaps with an addition of a proxy version of the questionnaire. An instrument should consider the cognitive age of the child, as some children develop at a slower pace than other children. The self-assessed version of the instrument should be understandable for children and their proxies, and the proxy version of the instrument should be available to adequately assess QoL in children too young or otherwise unable to complete a self-assessed version.

With this review, we aim to provide an overview of existing generic measures of QoL suitable for economic evaluations in children with mental health or psychosocial problems. We will include both preference-based measures (those with a value set (i.e., a collection of values for all possible states) suitable for economic evaluations) and profile-based measures (which provide different profiles or domains of QoL instead of a single score). A systematic review of psychometric properties in children with mental health issues of the identified instruments will be provided. Finally, the instruments will be scored using an in-house quality rating (available in Additional file 1) and the scoring results will be summarized visually in a decision tree. This decision tree can aid in a well-informed decision for choosing an instrument to measure QoL in children with mental health or psychosocial problems.

Methods

First, we undertook a systematic review of reviews (meta-review) (A.) of QoL instruments from which we identified all relevant instruments (B.). Next, we performed a systematic review of the psychometric properties of the identified instruments (C.). Lastly, the results were summarized in a decision tree (D.).

A. Meta-review of quality of life instruments

First, several databases were searched. For scientific literature we searched PubMed (Medline), PsycInfo, Embase, Econlit, and Web of Science. For grey literature we searched Google Scholar, Google, Cosmin, Picarta, and several online repositories for instruments (Kenniscentrum meetinstrumenten VUMC (http://www.kmin-vumc.nl, Proqolid, PROM, PROMIS). Search terms for the reviews can be found in Additional file 1. Thereafter, reference lists of relevant literature were checked for missing information.

Reviews concerning QoL instruments were included if they were aimed at studies for children below the age of 18, were aimed at QoL instruments that could be used in social or cognitive development, or in relation to psychiatric disorders of children, and were written in English. Reviews were excluded if they focused on curative or palliative treatment of somatic illnesses and conditions, screening or diagnostic intervention, or vaccinations. Furthermore, we searched recent articles which were not included in reviews for possible newly developed instruments. Selection and screening of the QoL reviews was performed by two authors (LS and APG), disagreement was resolved by consensus.

B. Identification of QoL instruments

The identified reviews were searched for relevant instruments. Instruments for QoL were included if they fulfilled the following criteria: the instrument should be available in English, the instrument should be aimed at children below the age of 18, the instrument should be a measure of generic health related quality of life suitable for use in social or cognitive development, or in relation to psychiatric disorders of children. Furthermore, we excluded instruments that were aimed at one specific disorder (disease specific instruments).

C. Systematic review of psychometric properties of QoL instruments

Subsequently, for each of the identified instruments a systematic review was performed to assess the psychometric properties of the instrument. Databases (PubMed, PsycInfo, Econlit, Web of Science and EMBASE) were searched for relevant studies using the following search terms and their synonyms (instruments/ questionnaires AND psychometric quality AND child/adolescence) combined with search terms specific for each of the instruments (abbreviations and full instrument name). A full overview of the search terms can be found in Additional file 1. Furthermore, reference lists of identified studies and reviews where checked for missing studies.

Studies were included if the psychometric research was performed in healthy individuals below the age of 18 years old or children with psychosocial, cognitive or psychiatric problems. Studies were excluded if they were not written in English or Dutch, or focused solely on children with somatic difficulties and did not include a healthy control group or group with psychosocial, cognitive or psychiatric problems group. Selection and screening of the studies was performed by either APG or LS. Psychometric properties (i.e. internal consistency, reliability, measurement error, content validity, structural validity, hypotheses testing, cross cultural validity, criterion validity, responsiveness, and feasibility) were scored (yes, explored this characteristic/ no, did not look at this characteristic) using the definitions provided by COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN). A summary of the definitions used can be found in the Additional file 1.

D. Quality scoring based on results

Quality of all instruments was scored based on several elements often described in literature. This led to a quality score per instrument. We used an in-house measure of quality that scored the quality of the instruments based on the number of relevant domains for mental health (including both functional as pathology domains), number of psychometric studies in general population children, number of psychometric studies in children with mental health or psychosocial problems, psychometric quality of instruments in children with mental health of psychosocial problems, and the existence of a value set. Further, we assessed the quality of the instrument with a self-developed quality score instrument and summarized the results in a decision tree that can be used to identify the best instruments for measuring quality of life in children with mental health disorders. Criteria and full summary per instrument can be found in Additional file 1.

Results

A. Review of reviews- QoL

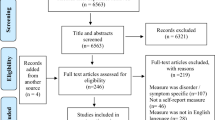

A total of 1636 reviews were identified. After the first selection based on title and abstract 43 reviews remained. No additional reviews were identified through our grey literature search. From these 43 reviews, 14 were not suitable for this review (reasons presented in PRISMA flow chart in Additional file 1), which led to 29 reviews included in this review of reviews.

B. Identification of QoL instruments

Of these 29 reviews, a total of 22 unique instruments were identified, see Table 1 for a summary. Of these 22 instruments, 14 had a proxy- and a self-report version, three instruments only had a proxy version and five only a self- report version. All identified instruments were available in English. An overview of the domains of QoL according to the WHO the instruments covered can be found in Fig. 1. A summary of the properties of the identified instruments can be found in Table 1.

C. Systematic review of psychometric quality of QoL instruments

A total of 195 papers were identified that fulfilled our inclusion criteria concerning psychometric research. A summary of the type of psychometric research in children can be found in Fig. 2. PRISMA flow charts for all searches are available in Additional file 1. A summary per instrument of all psychometric research on these instruments (n = 195) can be found in Additional file 1. Of the 195 studies 30 (15.4%) focused on psychometric properties of the identified instruments in children with impaired social or cognitive development or psychiatric problems. Ten out of 22 instruments had no information on their psychometric properties in children with mental health problems (i.e., 16D, 17D, AQOL, AHUM, CHSCS-PS, GCQ, HUI2/3, ITQOL, QOLPAV, TACQOL). Thirty papers investigated the psychometric properties in children with mental health problems, these 30 papers are discussed below.

Child health and illness profile (CHIP)

The CHIP had questionable to excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s alphas between 0.65–0.92 for the CHIP-AE [85], Cronbach’s alphas above 0.7 for the CHIP-CD/PRF [79] and Cronbach’s alphas between 0.71–0.82 for the CHIP-CE [76]) and fair to excellent test-retest reliability (ICC’s between 0.57–0.93) [85] in children with mental health problems. Structural validity was confirmed using linear principal factor model [79] and confirmatory factor analysis [76]. The questionnaires’ hypotheses testing abilities by investigating the discriminatory validity between age groups [85], genders [85], and illness groups [85], and by investigating the concurrent validity (comparison to ADHD-RS; r = −.35 [76] and r between −.18 and-.48 [79], and the SDQ r between-.28 and − .65 [79], CGI-.15 and − .30 [79], and FSI .28 and-.63 [79]).

Child health utility index 9 dimensions (CHU9D)

Psychometric research into the CHU9D has been conducted in two studies, one with overweight children [77] and one community sample receiving mental health services [86]. The CHU9D has acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78). Its hypotheses testing abilities were examined by convergence with the strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ; r = 0.49) [77] and PedsQL (r = 0.47) [86] and discriminant validity between different weight and ethnic groups [77].

Child health questionnaire (CHQ)

The CHQ was developed on a sample of children with ADHD by Landgraf et al. [87]. The CHQ-CF87 has moderate to good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alphas between 0.63–0.89) [87], hypotheses testing was assessed by known groups analyses between a school, ADHD, and end-stage renal disorder sample, different age groups and gender [87]. The CHQ-PF50 has a poor to excellent internal consistency in ADHD (Cronbach’s alphas of 0.54–0.90) [88]. Measurement error was assessed by investigating the standard error of measurement. Hypotheses testing was confirmed through significant Pearson correlation coefficients between the CHQ-PF50 and other clinical measures (ADHD-RS, CPRS, CGI-ADHD-S, CGI-ADHD-I) [88].

Child quality of life questionnaire (CQOL)

The CQOL has good internal consistency in children with psychiatric disorders (Cronbach’s alphas of 0.81–0.87). Reliability was assessed by means of test-retest correlations (r = 0.4–0.7) and intra-rater correlations (0.57). Reliability of individual domains was very variable, but the combined scores of the CQOL was of acceptable reliability [80].

EuroQol five dimensions-youth (EQ-5D-Y)

The EQ-5D-Y has very variable test-retest reliability (ICC’s, between 0.25 and 1) [89, 90]. Structural validity was confirmed through principal component analysis [91]. Hypotheses testing was assessed through discriminant validity between groups with asthma, diabetes, rheumatic disorder, and speech or hearing disorder. Concurrent validity was examined by looking at the correlation between the EQ-5D-Y and the TACQOL (low to moderate correlations) [89, 90], ADHD-RS (index scores between r = 0.31–0.27) [92], the CHQ-PF50 scale (index scores between r = 0.11–0.64) [92], clinical outcome scores [93] and KIDSCREEN-10 (strong correlation with index scores, but low correlations between domains and items) [91]. Responsiveness was examined by comparing those responding to treatment and those not responding to treatment [91], and by investigating changes in scores of patients who improved according to the Clinical Global Impression – of Improvement (CGI-I) scale versus those who did not improve [93].

Secnik et al. [94] developed a value set for children with ADHD based on standard gamble utility interviews with parents of children with ADHD.

KIDSCREEN

Development and pilot testing of the KIDSCREEN took place using a sample of more than 3000 European children and adolescents from the 13 different countries [95]. For all versions psychometric research has been conducted into the internal consistency, reliability, structural validity, and hypotheses testing in 34 different studies. The KIDSCREEN-52 has also been evaluated based on its content validity, and the KIDSCREEN-27 as well as the KIDSCREEN-52 have been evaluated in terms of feasibility. Research by Bouwmans et al. [91] and Clark et al. [96] used a sample of children with psychosocial problems. Bouwmans et al. (2014) assessed the KIDSCREEN-10 in children with ADHD in terms of structural validity through principal component analyses, responsiveness through comparing children who were responsive to treatment and those who were not, and hypotheses testing through concurrent validity by comparing the KIDSCREEN-10 to the EQ-5D (r = 0.56). Clark et al. (2015) analyzed the KIDSCREEN-52 and found acceptable to good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alphas of 0.72–0.89 for the child-version and 0.78–0.92 for the parent-version). Intra-rater reliability was poor to good (ICC’s between parents and their children between − 0.17 and 0.66). Hypotheses testing was analyzed by means of concurrent validity (comparison with ABAS-II; low correlations).

Questionnaire for measuring health-related quality of life in children and adolescent - revised version (KINDL-R)

The KINDL-R has poor to good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alphas for the Chinese child-version of the Kid KINDL of 0.47–0.77 and 0.55–0.79 for the parent-version [97]; Cronbach’s alphas of 0.53–0.82 for the child version and 0.62–0.86 for the parent version for the kid and kiddo-KINDL [98]).

Principal component analysis [97] and confirmatory factor analysis [98] confirmed its structural validity. Hypotheses testing was assessed by discriminant validity between healthy groups and groups suffering from global development delay and differences between age and sex groups, but did not find significant differences [97]. Differences were found between children with and without special health care needs and concurrent validity by comparing the instruments with corresponding SDQ scales (r = 0.33–0.49) [98].

Multidimensional students’ life satisfaction scale (MSLSS)

Research of Athay [99] assessed the psychometric quality of the brief MSLSS in a sample of children with psychosocial problems and found acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s alphas of 0.77) and a standard error of measurement of 0.4. Structural validity was confirmed by performing confirmatory factor analysis. Hypotheses testing was evaluated, showing some evidence for construct validity (a correlation with children hope and symptom severity), and discriminant validity (increased score with treatment, differences between different age groups and gender differences) [99].

Pediatric quality of life inventory (PedsQL)

The PedsQL has acceptable to good internal consistency in children with ADHD, and in children with intellectual disabilities (all Cronbach’s alphas above .70) [73, 100,101,102], but in Dutch children with psychiatric disorders unacceptable to questionable internal validity for children 6–7 (Cronbach’s alphas of 0.40–0.63), questionable to good internal consistency for children 8–12 (0.63–0.85) and 13–18 (0.57–0.87) years old and parents (0.69–0.87) for parents of children of all ages [103]. It has excellent interparent reliability (ICC’s of 0.86–0.91) [103], but poor inter-rater reliability (ICC’s between the self-administration version and the parent version of 0.13–0.35) [100]. Structural validity was confirmed through exploratory factor analyses [73, 102], and confirmatory factor analysis [103]. The PedsQL’s hypotheses testing abilities were examined by looking at convergent validity (comparison to the CBCL [103]; (r = 0.24 children-rated and r = − 0.62 for parent-rated), and the SDQ [102] questionnaire (r = − 0.70–0.27). Parent-child agreement was moderate (r = 0.59–0.69) [101]. Discriminant validity was examined by assessing whether the PedsQL could distinguish between several known groups [73, 100,101,102,103]. Feasibility of the PedsQL was assessed by looking at the percentage of missing values which was less than 4.0% [101, 102].

Quality of well-being scale (QWB)

The QWB has good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alphas of 0.83 and 0.84) and excellent intra-rater reliability (ICC = 0.77). Hypotheses testing was evaluated with construct validity (confirmed by comparing the QWB-SA mental health scale to the mental health scales of the SF-36 (r = 0.66–0.72), EQ-5D (r = 0.61), HUI (r = 0.59–0.63), and POMS (r = 0.77)) [104].

TNO AZL preschool quality of life (TAPQOL)

The TAPQOL has fair to good internal consistency in children with language delays (Cronbach’s alphas of 0.63–0.82) and a low percentage of missing values (1.9–6.7%). Structural validity was confirmed by performing factor analysis and hypotheses testing was evaluated using known groups, receiver operating characteristics curves and comparison to a questionnaire for language delays [105].

Youth quality of life instrument (YQOL)

The YQOL has acceptable to excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s alphas between 0.77–0.96) [63, 106] and good to excellent test-retest reliability (ICC = 0.74–0.85) [63, 106]. Hypotheses testing was assessed by comparing the YQOL to the Children’s Depression Inventory (r = 0.58) [63], the Functional Disability Inventory (r = 0.26) [63], the KINDL (r = 0.73) [63] and PedsQL’s comparable dimensions (r = 0.21–0.53) [106]. Discriminant validity was assessed by comparing known groups [63, 106].

Quality scoring of instruments

All instruments were scored on quality using an in-home instrument available in Additional file 1. The full quality score per instrument is available in the Additional file 1. A summary score per instrument is available in Table 1. The highest scoring instrument was the CHU9D with a score of 7 out of 10 points, and the lowest scoring instrument was the GCQ with 0 out of 10 points. These results led to a decision aid (Fig. 3) in which the instruments are sorted by quality score. Highest quality scores are ranked first.

Decision tree for choosing a quality of life instrument for children with mental health problems. Instruments are rated and ordered according to a rating system available in Additional file 1. Equal quality scores are represented by equal numbers. The higher the number the better the quality rating

Discussion

We found that none of the instruments was perfect for use in economic evaluation of child and adolescent mental health care as all instruments had disadvantages, ranging from lack of psychometric research, no proxy version, not being suitable for young children, no age-specific value set for children under 18, to insufficient focus on relevant domains (e.g. social and emotional domains). While around 50% of instruments had items that assessed social relations or psychological state, most just included a relatively general question probing a single aspect of psychosocial related problems. To fully assess the impact of psychosocial and mental health problems on quality of life, it is of the utmost importance that the outcome reflects all aspects of QoL that are affected, and not merely physical domains.

When one wants to perform a cost-utility analysis, most guidelines [107, 108], recommend to use the EQ-5D-Y. The advantage of this instrument is that both a proxy and a self-report version are available. A major disadvantage is that there is only an adult value set available. Studies have shown that the adult value set is not suitable for use in children and adolescents, given that health states described for adults are valued differently by children [109]. Different aspects are relevant for QoL in children, adolescents, or adults, making it questionable whether the adult items are relevant and important for QoL in children. Another major disadvantage to using the EQ-5D-Y for cost-utility analysis of child mental health care is the lack of questions that portrayed psychosocial problems. Only feelings of anxiety or depression are assessed with the EQ-5D-Y, which leaves externalizing and social problems neglected. Our review highlights the CHU9D as a more suitable instrument for measuring QoL if one plans to perform an economic evaluation, and the CHIP as a general measure for QOL in children with mental health and psychosocial problems.

Often, it is assumed measuring QoL in children below the age of 8 is not feasible and reliable. Proxy versions of instruments can be used in this age group, but these have their limitations as well. Some studies have reported poor to fair agreements between self and proxy versions of instruments (e.g., 35, 49, 50). Possibly, this difference is due to a different meaning of certain concepts for children than for adults. Moreover, it is unclear what determines high QoL in young children and it is hard to assess what high QoL is at a young age. Another problem associated with the use of proxy measures is that a proxy rater (often a parent) is close to the child thus the proxy’s interpretation of the QoL of the child may be affected by the child’s problems, leading to incorrect approximations of the child’s QoL. Where possible, it is recommended to let an individual report on their own QoL, possibly with an addition of a proxy version of the questionnaire. An instrument should consider the cognitive age of the child [16], at this moment none of the identified instruments does this. Another problem in current instruments is the poor to fair agreement between self and proxy versions of instruments [98, 110, 111]. Other studies reported moderate to high agreement [19, 101] between self and parent versions of questionnaires, but found large differences dependent on the domain, with higher correlations in physical domains [38]. However, most psychosocial interventions are aimed at changes in psychosocial domains, therefore one does not expect change in physical domains. Future research should focus on making age adjustable versions of questionnaires, assessing domains suitable for children with mental health disorders.

Interestingly, studies that compared generic QoL instruments with disease specific instruments measuring symptoms of mental health disorders found mostly weak to moderate correlations between the two [63, 76, 77, 79, 88, 92, 98, 102,103,104, 106]. These significant but relatively low correlations indicate that generic QoL instruments and disease specific instruments measure separate but related constructs. This indicates the added benefit of generic measures of QoL on top of disease specific measures in both research and clinical practice, since this gives a more complete overview of the child’s state. However, at this moment a perfect instrument for this purpose does not exists since most QoL measures are developed for children with somatic problems. The development of instruments that are suitable to measure QoL in children suffering from psychosocial or mental health problems is of utmost importance.

While this review provides a thorough overview of available instruments to measure QoL in children with psychosocial or mental health problems, some limitations should be noted. We did not have the resources to hold focus groups or interviews, in which children participate to assess the relevance of all items of instruments for use in children with mental health or psychosocial problems. To comprehensively assess which domains are relevant for children and adolescents compared to adults, children’s own appraisal of relevant domains, should be included in a measure for QoL for children (see also [112]). These focus groups or interviews should be aimed at assessing the relevance of certain domains and exploration of additional relevant domains in different age groups, and perhaps even different psychiatric classifications.

We did however, rate the inclusion of relevant domains based on the WHO definition. Additionally, we assessed the quality of the instruments with a newly developed, as we felt this fulfilled our requirements better than any existing instruments. The combination of quality assessment for both clinical practice and economic evaluations is relatively new, and therefore no available instrument met our criteria. While our assessment is transparent, an existing instrument could have led to different ratings. Furthermore, since many excellent reviews already summarized relevant instruments to measure QoL in children with mental health and psychosocial problems, we decided to perform a meta-review, and not a systematic search of individual studies. This approach could have caused us to overlook relevant instruments. Furthermore, we included children below the age of 18, but there is a growing international movement toward youth mental health services, which typically spans adolescence and young adulthood (ages 12–24). Future research is warranted on suitable instruments to measure QoL in this age group. Lastly, while we did a thorough search through all relevant databases and grey literature, we only included English or Dutch language articles.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, this review provides an overview of the generic instruments available to measure QoL in children with mental health problems and their psychometric properties. This led to a decision aid which incorporates the results of the current study (Fig. 3), to aid in the choice of an instrument for QoL in children with mental health or psychosocial problems. Future research should focus on making age adjustable versions of questionnaires that take cognitive age into account, assessing domains suitable for children with mental health disorders.

Availability of data and materials

No data was used to produce this manuscript. All materials are available in the article and supplementary materials.

Abbreviations

- 16D:

-

Sixteen Dimensional measure of HRQoL

- 17D:

-

Seventeen Dimensional measure of HRQoL

- AQOL-MHS:

-

Adolescent Quality of Life-Mental Health Scale

- ADHD:

-

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- CHIP:

-

Child Health and Illness Profile

- CHQ:

-

Child Health Questionnaire

- CHU9D:

-

Child health Utility index 9 dimensions

- CQOL:

-

Child Quality of Life Questionnaire

- CHSCS-PS:

-

Comprehensive Health Status Classification System – Preschool

- COSMIN:

-

COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments

- EQ-5D-Y:

-

EuroQol five dimensions-Youth

- GCQ:

-

Generic children’s quality of life questionnaire

- HUI:

-

Health Utilities Index

- ICC:

-

Intraclass correlation coefficient

- ITQOL:

-

Infant and Toddler Quality of Life Questionnaire

- MSLSS:

-

Multidimentional students’ life satisfaction scale

- OECD:

-

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

- PedsQL:

-

Pediatric quality of Life inventory

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- QOLPAV:

-

Quality of Live Profile: Adolescent Version

- QWB:

-

Quality of well-being scale

- SDQ:

-

Strengths and difficulties questionnaire

- TACQOL:

-

TNO-AZL-Child-Quality-of-Life

- TAPQOL:

-

TNO AZL preschool Quality of Life

- YQOL:

-

Youth Quality of life instrument

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

The WHO World Mental Health Survey Consortium. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization world mental health surveys. JAMA. 2004;291(21):2581–90.

OECD. In: OECD Health Policy Studies OP, editor. Making mental health count: the social and economic costs of neglecting mental health care; 2014.

Kessler R, Angermeyer M, Anthony J, De Graaf R, Demyttenaere K, Gasquet I, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the world health organization’s world mental health survey initiative. World Psychiatry. 2007;6(3):168.

Groenman A, Janssen T, Oosterlaan J. Childhood psychiatric disorders as risk factor for subsequent substance abuse: a meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(7):556–69.

Veldman K, Reijneveld SA, Ortiz JA, Verhulst FC, Bultmann U. Mental health trajectories from childhood to young adulthood affect the educational and employment status of young adults: results from the trails study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(6):588–93.

Esch P, Bocquet V, Pull C, Couffignal S, Lehnert T, Graas M, et al. The downward spiral of mental disorders and educational attainment: a systematic review on early school leaving. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:237.

Low NC, Dugas E, O'Loughlin E, Rodriguez D, Contreras G, Chaiton M, et al. Common stressful life events and difficulties are associated with mental health symptoms and substance use in young adolescents. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:116.

Johnston DW, Schurer S, Shields MA. Exploring the intergenerational persistence of mental health: evidence from three generations. J Health Econ. 2013;32(6):1077–89.

Wehmeier PM, Schacht A, Barkley RA. Social and emotional impairment in children and adolescents with Adhd and the impact on quality of life. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(3):209–17.

Subramaniam M, Soh P, Vaingankar JA, Picco L, Chong SA. Quality of life in obsessive-compulsive disorder: impact of the disorder and of treatment. CNS Drugs. 2013;27(5):367–83.

Bertha EA, Balazs J. Subthreshold depression in adolescence: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;22(10):589–603.

The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (Whoqol). Position Paper from the World Health Organization. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41(10):1403–9.

World Health Organization. Whoqol: Measuring Quality of Life. 1997.

Rabarison KM, Bish CL, Massoudi MS, Giles WH. Economic evaluation enhances public health decision making. Front Public Health. 2015;3:164.

Endicott J, Nee J, Yang R, Wohlberg C. Pediatric quality of life enjoyment and satisfaction questionnaire (Pq-les-Q): reliability and validity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(4):401–7.

Sagvolden T, Johansen EB, Aase H, Russell VA. A dynamic developmental theory of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (Adhd) predominantly hyperactive/impulsive and combined subtypes. Behav Brain Sci. 2005;28(3):397–419.

Coghill D, Danckaerts M, Sonuga-Barke E, Sergeant J, ADHD European Guidelines Group. Practitioner review: quality of life in child mental health--conceptual challenges and practical choices. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50(5):544–61.

Starfield B, Bergner M, Ensminger M, Riley A, Ryan S, Green B, et al. Adolescent health status measurement: development of the child health and illness profile; 1993. p. 430–5.

Danckaerts M, Sonuga-Barke EJS, Banaschewski T, Buitelaar J, Döpfner M, Hollis C, et al. The quality of life of children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;19(2):83–105.

Garnock-Jones KP, Keating GM. Atomoxetine: a review of its use in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Paediatr Drugs. 2009;11(3):203–26.

Coghill D. The impact of medications on quality of life in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. CNS Drugs. 2010;24(10):843–66.

Payakachat N, Tilford JM, Kovacs E, Kuhlthau K. Autism Spectrum disorders: a review of measures for clinical, health services and cost–effectiveness applications. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2012;12(4):485–503.

Epstein JN, Weiss MD. Assessing Treatment Outcomes in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Narrative Review. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2012;14(6):PCC.11r01336.

Dey M, Landolt MA, Mohler-Kuo M. Health-related quality of life among children with mental disorders: a systematic review. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(10):1797–814.

Ikeda E, Hinckson E, Krägeloh C. Assessment of quality of life in children and youth with autism Spectrum disorder: a critical review. Qual Life Res. 2014;23(4):1069–85.

Janssens A, Rogers M, Gumm R, Jenkinson C, Tennant A, Logan S, et al. Measurement properties of multidimensional patient-reported outcome measures in Neurodisability: a systematic review of evaluation studies. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016;58(5):437–51.

Coghill D, Banaschewski T, Soutullo C, Cottingham MG, Zuddas A. Systematic review of quality of life and functional outcomes in randomized placebo-controlled studies of medications for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;26(11):1283–307.

Rajmil L, Herdman M, de Sanmamed M-JF, Detmar S, Bruil J, Ravens-Sieberer U, et al. Generic health-related quality of life instruments in children and adolescents: a qualitative analysis of content. J Adolesc Health. 2004;34(1):37–45.

Solans M, Pane S, Estrada MD, Serra-Sutton V, Berra S, Herdman M, et al. Health-related quality of life measurement in children and adolescents: a systematic review of generic and disease-specific instruments. Value Health. 2008;11(4):742–64.

De Kroon M, Hodiamont P. Kwaliteit Van Leven, Gemeten in De Kinderpsychiatrie; 2008.

Paltzer J, Barker E, Witt WP. Measuring the health-related quality of life (Hrqol) of young children in resource-limited settings: a review of existing measures. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(6):1177–87.

Cremeens J, Eiser C, Blades M. Characteristics of health-related self-report measures for children aged three to eight years: a review of the literature. Qual Life Res. 2006;15(4):739–54.

Schmidt L, Garratt A, Fitzpatrick R. Child/parent-assessed population health outcome measures: a structured review. Child Care Health Dev. 2002;28(3):227–37.

Ravens-Sieberer U, Erhart M, Wille N, Wetzel R, Nickel J, Bullinger M. Generic health-related quality-of-life assessment in children and adolescents. Pharmacoeconomics. 2006;24(12):1199–220.

Harding L. Children’s quality of life assessments: a review of generic and health related quality of life measures completed by children and adolescents. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2001;8(2):79–96.

Spieth LE, Harris CV. Assessment of health-related quality of life in children and adolescents: an integrative review. J Pediatr Psychol. 1996;21(2):175–93.

Landgraf JM, Maunsell E, Speechley KN, Bullinger M, Campbell S, Abetz L, et al. Canadian-French, German and Uk Versions of the Child Health Questionnaire: Methodology and Preliminary Item Scaling Results. Qual Life Res. 1998;7:433–45.

Galloway H, Newman E. Is there a difference between child self-ratings and parent proxy-ratings of the quality of life of children with a diagnosis of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (Adhd)? A systematic review of the literature. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 2017;9(1):11–29.

Klassen AF. Quality of life of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2005;5(1):95–103.

De Civita M, Regier D, Alamgir AH, Anis AH, FitzGerald MJ, Marra CA. Evaluating health-related quality-of-life studies in Paediatric populations. Pharmacoeconomics. 2005;23(7):659–85.

Msall ME. Measuring functional skills in preschool children at risk for neurodevelopmental disabilities. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2005;11(3):263–73.

Matza LS, Stoeckl MN, Shorr JM, Johnston JA. Impact of Atomoxetine on health-related quality of life and functional status in patients with Adhd. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2006;6(4):379–90.

Upton P, Lawford J, Eiser C. Parent–child agreement across child health-related quality of life instruments: a review of the literature. Qual Life Res. 2008;17(6):895.

Evans J, Seri S, Cavanna AE. The effects of Gilles De La Tourette syndrome and other chronic tic disorders on quality of life across the lifespan: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;25(9):939–48.

Coghill D, Danckaerts M, Sonuga-Barke E, Sergeant J. Practitioner review: quality of life in child mental health–conceptual challenges and practical choices. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50(5):544–61.

Grosse Schlarmann J, Metzing-Blau S, Schnepp W. The use of health-related quality of life (hrqol) in children and adolescents as an outcome criterion to evaluate family oriented support for young carers in germany: an integrative review of the literature. BMC Public Health. 2008;8(1):414.

Cavanna AE, David K, Bandera V, Termine C, Balottin U, Schrag A, et al. Health-related quality of life in Gilles De La Tourette syndrome: a decade of research. Behav Neurol. 2013;27(1):83–93.

Ravens-Sieberer U, Bullinger M. Assessing health-related quality of life in chronically ill children with the German Kindl: first psychometric and content analytical results. Qual Life Res. 1998;7(5):399–407.

Feeney R, Desha L, Ziviani J, Nicholson JM. Health-related quality-of-life of children with speech and language difficulties: a review of the literature. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2012;14(1):59–72.

Gomersall T, Spencer S, Basarir H, Tsuchiya A, Clegg J, Sutton A, et al. Measuring quality of life in children with speech and language difficulties: a systematic review of existing approaches. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2015;50(4):416–35.

Jonsson U, Alaie I, Löfgren Wilteus A, Zander E, Marschik PB, Coghill D, et al. Annual research review: quality of life and childhood mental and Behavioural disorders–a critical review of the research. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2017;58(4):439–69.

Lee Y-c, Yang H-J, Chen VC-H, Lee W-T, Teng M-J, Lin C-H, et al. Meta-analysis of quality of life in children and adolescents with Adhd: by both parent proxy-report and child self-report using Pedsql™. Res Dev Disabil. 2016;51:160–72.

Vieira J, Silva FR. Quality of life in children with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Acta Med Port. 2016;29(9):549–55.

Varni JW, Seid M, Rode CA. The Pedsql: Measurement Model for the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory; 1999. p. 126–39.

Zekovic B, Renwick R. Quality of life for children and adolescents with developmental disabilities: review of conceptual and methodological issues relevant to public policy. Disabil Soc. 2003;18(1):19–34.

Tavernor L, Barron E, Rodgers J, McConachie H. Finding out what matters: validity of quality of life measurement in young people with Asd. Child Care Health Dev. 2013;39(4):592–601.

Chiang H-M, Wineman I. Factors associated with quality of life in individuals with autism Spectrum disorders: a review of literature. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2014;8(8):974–86.

Coluccia A, Ferretti F, Fagiolini A, Pozza A. Quality of life in children and adolescents with obsessive–compulsive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:597.

Eiser C, Morse R. Can parents rate their Child’s health-related quality of life? Results of a systematic review. Qual Life Res. 2001;10(4):347–57.

Vogels T, Verrips GHW, Verloove-Vanhorick SP, Fekkes M, Kamphuis RP, Koopman HM, et al. Measuring health-related quality of life in children: the development of the Tacqol parent form. Qual Life Res. 1998;7(5):457–65.

Fekkes M, Theunissen NCM, Brugman E, Veen S, Verrips EGH, Koopman HM, et al. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Tapqol: a health-related quality of life instrument for 1-5-year-old children. Qual Life Res. 2000;9(8):961–72.

Weber S, Jud A, Landolt M. Quality of life in maltreated children and adult survivors of child maltreatment: a systematic review. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(2):237–55.

Patrick DL, Edwards TC, Topolski TD. Adolescent quality of life, part ii: initial validation of a new instrument. J Adolesc. 2002;25(3):287–300.

Adlard N, Kinghorn P, Frew E. Is the Uk Nice “reference case” influencing the practice of pediatric quality-adjusted life-year measurement within economic evaluations? Value Health. 2014;17(4):454–61.

Griebsch I, Coast J, Brown J. Quality-adjusted life-years lack quality in pediatric care: a critical review of published cost-utility studies in child health. Pediatrics. 2005;115(5):e600–e14.

Richardson JRJ, Peacock SJ, Hawthorne G, Iezzi A, Elsworth G, Day NA. Construction of the descriptive system for the assessment of quality of life Aqol-6d utility instrument. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:38.

Chen G, Ratcliffe J. A review of the development and application of generic multi-attribute utility instruments for Paediatric populations. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33(10):1013–28.

Wille N, Badia X, Bonsel G, Burström K, Cavrini G, Devlin N, et al. Development of the Eq-5d-Y: a child-friendly version of the Eq-5d. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(6):875–86.

Wu EQ, Hodgkins P, Ben-Hamadi R, Setyawan J, Xie J, Sikirica V, et al. Cost effectiveness of pharmacotherapies for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. CNS Drugs. 2012;26(7):581–600.

Huebner ES. Preliminary development and validation of a multidimensional life satisfaction scale for children. Psychol Assess. 1994;6(2):149–58.

Raphael D, Rukholm E, Brown I, Hill-Bailey P. The quality of life profile—adolescent version: background, description, and initial validation. J Adolesc Health. 1996;19(5):366–75.

Klassen AF, Landgraf JM, Lee SK, Barer M, Raina P, Chan HW, et al. Health related quality of life in 3 and 4 year old children and their parents: preliminary findings about a new questionnaire. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1(1):81.

Jafari P, Ghanizadeh A, Akhondzadeh S, Mohammadi MR. Health-related quality of life of Iranian children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Qual Life Res. 2011;20(1):31–6.

Stevens K. Developing a descriptive system for a new preference-based measure of health-related quality of life for children. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(8):1105–13.

Apajasal M, Sintonen H, Holmberg C, Sinkkonen J, Aalberg V, Pihko H, et al. Quality of life in early adolescence: a sixteen-dimensional health-related measure (16d). Qual Life Res. 1996;5(2):205–11.

Schacht A, Escobar R, Wagner T, Wehmeier PM. Psychometric properties of the quality of life scale child health and illness profile-child edition in a combined analysis of five Atomoxetine trials. Atten Deficit Hyperact Disord. 2011;3(4):335–49.

Frew EJ, Pallan M, Lancashire E, Hemming K, Adab P, WAVES Study co-investigators. Is utility-based quality of life associated with overweight in children? evidence from the uk waves randomised controlled study. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15:211.

Apajasalo M, Rautonen J, Holmberg C, Sinkkonen J, Aalberg V, Pihko H, et al. Quality of life in pre-adolescence: a 17-dimensional health-related measure (17d). Qual Life Res. 1996;5(6):532–8.

Riley AW, Coghill D, Forrest CB, Lorenzo MJ, Ralston SJ, Spiel G, et al. Validity of the health-related quality of life assessment in the adore study: parent report form of the chip-child edition; 2006. p. I63–71.

Graham P, Stevenson J, Flynn D. A new measure of health-related quality of life for children: preliminary findings. Psychol Health. 1997;12(5):655–65.

Beusterien KM, Yeung J-E, Pang F, Brazier J. Development of the multi-attribute adolescent health utility measure (Ahum). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:102.

Saigal S, Rosenbaum P, Stoskopf B, Hoult L, Furlong W, Feeny D, et al. Development, reliability and validity of a new measure of overall health for pre-school children. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:243–57.

Collier J, MacKinlay D, Phillips D. Norm values for the generic Children’s quality of life measure (Gcq) from a large school-based sample. Qual Life Res. 2000;9(6):617–23.

Kaplan RM, Bush JW, Berry CC. Health status: types of validity and the index of well-being. Health Serv Res. 1976;11(4):478–507.

Rajmil L, Serra-Sutton V, Alonso J, Starfield B, Riley AW, Vázquez JR, et al. The spanish version of the child health and illness profile-adolescent edition (chip-ae); 2003. p. 303–13.

Furber G, Segal L. The validity of the child health utility instrument (Chu9d) as a routine outcome measure for use in child and adolescent mental health services; 2015. p. 22.

Landgraf JM, Abetz LN. Functional status and well-being of children representing three cultural groups: initial self-reports using the chq-Cf87. Psychol Health. 1997;12(6):839–54.

Rentz AM, Matza LS, Secnik K, Swensen A, Revicki DA. Psychometric validation of the child health questionnaire (chq) in a sample of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(3):719–34.

Stochl J, Croudace T, Perez J, Birchwood M, Lester H, Marshall M, et al. Usefulness of eq-5d for evaluation of health-related quality of life in young adults with first-episode psychosis; 2013. p. 1055–63.

Willems DCM, Joore MA, Nieman FHM, Severens JL, Wouters EFM, Hendriks JJE. Using eq-5d in children with asthma, rheumatic disorders, diabetes, and speech/language and/or hearing disorders; 2009. p. 391–9.

Bouwmans C, van der Kolk A, Oppe M, Schawo S, Stolk E, van Agthoven M, et al. Validity and responsiveness of the Eq-5d and the Kidscreen-10 in children with Adhd. Eur J Health Econ. 2014;15(9):967–77.

Matza LS, Secnik K, Mannix S, Sallee FR. Parent-proxy Eq-5d ratings of children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in the us and the Uk. Pharmacoeconomics. 2005;23(8):777–90.

Byford S. The validity and responsiveness of the eq-5d measure of health-related quality of life in an adolescent population with persistent major depression; 2013. p. 101–10.

Secnik K, Matza LS, Cottrell S, Edgell E, Tilden D, Mannix S. Health state utilities for childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder based on parent preferences in the United Kingdom; 2005. p. 56–70.

Ravens-Sieberer U, Gosch A, Rajmil L, Erhart M, Bruil J, Duer W, et al. Kidscreen-52 quality-of-life measure for children and adolescents. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2005;5(3):353–64.

Clark BG, Magill-Evans JE, Koning CJ. Youth with autism Spectrum disorders: self- and proxy-reported quality of life and adaptive functioning. Res Dev Disabil. 2015;30(1):57–64.

Chan PLC, Ng SSW, Chan DYL. Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the kid-Kindlr questionnaire for measuring the health-related quality of life of school-aged children. Hong Kong J Occup Ther. 2014;24(1):28–34.

Erhart M, Ellert U, Kurth B-M, Ravens-Sieberer U. Measuring Adolescents' Hrqol via self reports and parent proxy reports: an evaluation of the psychometric properties of both versions of the Kindl-R instrument. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:77.

Athay MM, Kelley SD, Dew-Reeves SE. Brief multidimensional Students' life satisfaction scale-Ptpb version (Bmslss-Ptpb): psychometric properties and relationship with mental health symptom severity over time. Admin Pol Ment Health. 2012;39(1):30–40.

Limbers CA, Ripperger-Suhler J, Heffer RW, Varni JW. Patient-reported pediatric quality of life inventory™ 4.0 generic Core scales in pediatric patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and comorbid psychiatric disorders: feasibility, reliability, and validity. Value Health. 2011;14(4):521–30.

Varni JW, Burwinkle TM. The Pedsql™ as a patient-reported outcome in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a population-based study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:26.

Viecili MA, Weiss JA. Reliability and validity of the pediatric quality of life inventory with individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2015;120(4):289–301.

Bastiaansen D, Koot HM, Bongers IL, Varni JW, Verhulst FC. Measuring quality of life in children referred for psychiatric problems: psychometric properties of the pedsql 4.0 generic core scales. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:489–95.

Sarkin AJ, Groessl EJ, Carlson JA, Tally SR, Kaplan RM, Sieber WJ, et al. Development and validation of a mental health subscale from the quality of well-being self-administered. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(7):1685–96.

van Agt HME, Essink-Bot M-L, van der Stege HA, de Ridder-Sluiter JG, de Koning HJ. Quality of life of children with language delays. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(5):1345–55.

Jiang X-Y, Wang H-M, Edwards TC, Chen Y-P, Lv Y-R, Patrick DL. Measurement properties of the chinese version of the youth quality of life instrument - weight module (yqol-w). PLoS ONE. 2014;9(9):e109221.

NICE. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Diagnosis and Management. [Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/ guidance/cg72].

Dutch National Health Care Institute. Guideline for Economic Evaluations in Healthcare. 2016.

Kind P, Klose K, Gusi N, Olivares PR, Greiner W. Can adult weights be used to value child health states? Testing the influence of perspective in valuing Eq-5d-Y. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(10):2519–39.

Baydur H, Ergin D, Gerçeklioğlu G, Eser E. Reliability and validity study of the Kidscreen health-related quality of life questionnaire in a Turkish child/adolescent population. Anadolu Psikiyatri Dergisi. 2016;17(6):496–505.

Hao Y, Tian Q, Lu Y, Chai Y, Rao S. Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the pediatric quality of life inventory™ 4.0 generic Core scales. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(8):1229–33.

Ravens-Sieberer U, Karow A, Barthel D, Klasen F. How to assess quality of life in child and adolescent psychiatry. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2014;16(2):147–58.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was funded by the Netherlands organization for health research and development (grant number 729300201) to A.P. Groenman. This funding source had no role in the design of this study and will not have any role during its execution, analyses, interpretation of the data, or decision to submit results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

APG and LS conducted the searches, data extraction, interpretation of the data. APG wrote the manuscript. APG, DKW, JOM, PJH, DEMCJ, EB, KV, JM, MEvdAvM, SAR, CDD and BJvdH designed the study. All authors reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Annabeth P. Groenman, Lisan Spiegelaar, Pieter J. Hoekstra, Danielle E.M.C. Jansen, Erik Buskens, Karin Vermeulen, Jochen Mierau, Daphne Kann-Weedage, Sijmen A. Reijneveld, M. Elske van den Akker-van Marle, Carmen D. Dirksen and Barbara J. van den Hoofdakker have no conflicts of interest to report.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Appendix 1.

Search terms instruments. Appendix 2. Search terms psychometric quality. Appendix 3. Cosmin Definitions. Appendix 4. Quality scores Questionnaires. Appendix 5. PRISMA flow charts Review of reviews. Appendix 6. Prisma Flow chart Psychometric characteristics. Appendix 7. Summary Tables of psychometric research. Appendix 8. Domains of QoL per age group.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Mierau, J.O., Kann-Weedage, D., Hoekstra, P.J. et al. Assessing quality of life in psychosocial and mental health disorders in children: a comprehensive overview and appraisal of generic health related quality of life measures. BMC Pediatr 20, 329 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-020-02220-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-020-02220-8