Abstract

Background

Nasal colonization with bacterial pathogens is associated with risk of invasive respiratory tract infections, but the related information for Chinese healthy children is scarce.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted with healthy children from 6 kindergartens in the Chaoshan region, southern China during 2011–2012. Nasal swabs were examined for five common bacterial pathogens: Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Haemophilus parainfluenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and Staphylococcus aureus.

Results

Among 1,088 children enrolled, 79.6 % (866) were target-bacterial carriers, of which 34.4 % (298/866) were positive for ≥2 bacteria species. The most common pathogen in the bacterial carriers was M. catarrhalis (76.6 %), followed by S. pneumoniae (26.6 %), S. aureus (21.8 %), H. parainfluenzae (12.7 %), and H. influenzae (2.3 %). Multiple logistic regression analyses showed negative associations between age and the overall or multiple bacterial carriage, and between the father’s education level and multiple bacterial carriage (all p < 0.05). Age was negatively associated with the carriage of M. catarrhalis and S. pneumoniae, and positively associated with the S. aureus carriage (all p < 0.0001).

Conclusions

This study shows high nasal carriage of common pathogenic bacteria and coexistence of multiple pathogens in healthy Chaoshan kindergarten children, with M. catarrhalis as the commonest colonizer. Increasing age of children and higher paternal education are associated with lower risk of bacterial carriage. Longitudinal follow-up studies would be helpful for better understanding the infection risk in bacterial pathogen carriers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Respiratory tract infections (RTIs) are a major cause of death in children worldwide. Although viruses are main RTI pathogens, bacteria are responsible for some localized RTIs such as sinusitis or pneumonia. Globally, Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae are the leading pathogens of RTIs, S. pneumoniae caused 0.8 million deaths in children younger than 5 years in 2000 [1], and H. influenzae accounted for at least 0.4 million deaths in 2006 [2]. Moraxella catarrhalis, along with S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae, constitutes top three bacterial pathogens causing community-acquired RTIs [3, 4]. Staphylococcus aureus is an important cause of infections both in the community and hospital, including pneumonia and neonatal sepsis [5, 6].

Nasopharyngeal colonization with respiratory pathogens is a precursor to the onset of RTI [7]. Most colonization remains asymptomatic, but it can become invasive in susceptible hosts [7]. Bacterial colonization can progress into primary infection or secondary superinfection after viral infection in its host [8]. Besides, asymptomatic carriers are a recognized source of community-acquired RTIs [6, 7, 9].

The carriage of bacterial pathogens is higher in children than in adults [7, 9]. Previous studies have shown that S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, and/or M. catarrhalis can colonize in children between 1 and 30 months [7], or even as early as 8–10 days after birth [10]. Up to one hundred per cent of infants aged 1 year were reported to carry at least one respiratory pathogens [7]. Multiple carriage of respiratory bacterial pathogens is common in children, particularly in kindergartens [7, 9] because of easier transmission through close contact.

Many studies have reported nasal carriage of bacterial pathogens in children, but most of them focused on one or two pathogens [9]. Little is known about bacterial pathogens in Chinese healthy children. Thus, we have investigated the nasal carriage of five common bacterial pathogens (S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, H. parainfluenzae, M. catarrhalis, and S. aureus) in healthy kindergarten children in China.

Methods

Study site and population

In this cross-sectional study, 6 urban/rural kindergartens in the Chaoshan region (Shantou, Jieyang, and Chaozhou cities), Guangdong, southern China were selected through convenient sampling during October 2011 and January 2012. This study period was selected to avoid summer, winter, or national holidays and conflicts with kindergartens’ schedules. The Chaoshan region is in the subtropical zone, with a population of 14.6 million, approximately 2,100 kindergartens and 0.4 million kindergarten children in 2011 [11–13].

Eligible participants were screened 1 week prior to the sample collection by sending a pretested questionnaire (Additional file 1) to the parents/guardians of the kindergarten children to collect the demographic and medical information, including a history of vaccination, respiratory symptoms in the past 6 months, antibiotic consumption within previous 3 months, and immunodeficient conditions. Further, a phone call with parents/guardians was made to reassure the eligibility in the morning of sample collection days.

Included in the study were all children aged 2–6 years old, except those with acute respiratory symptoms (<72 h of the onset), antibiotic consumption within 7 days of enrolment, immunodeficient conditions, and any unfit physical condition for swab collection, or those without consent.

Sample collection

Our trained staff took a nasal swab from one nostril of each participant as per WHO guidelines [14]. The swab was inoculated immediately onto blood agar and chocolate agar plates on the study site, transported in anaerobic jars (AnaeroPack Rectangular Jar and AnaeroPack-MicroAero, Mitsubishi Gas Chemical Company, Japan) to our laboratory within 1–3 h, and incubated in 5 % CO2 at 35 °C for 24–48 h for isolation and identification.

Microbial isolation and identification

The specimens were tested for the presence of S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, H. parainfluenzae, M. catarrhalis, and S. aureus according to the standard laboratory procedures. S. pneumoniae was identified by colony morphology, Gram staining, catalase and α-haemolysis, and optochin susceptibility. H. influenzae and H. parainfluenzae were identified by growth on chocolate agar with bacitracin, colony morphology, Gram staining, catalase reaction, and requirement of X (hemin), V (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide), and X + V factors (Oxoid, Basingstoke, the United Kingdom). M. catarrhalis was identified by colony morphology, Gram staining, oxidase and DNase tests, and growth on chocolate agar with vancomycin, trimethoprim, amphotericin B and acetazolamide. S. aureus was identified by colony morphology, Gram staining, β-haemolysis, and catalase and coagulase tests.

Statistical analysis

We used Chi-square test to compare differences in the proportions of categorical variables, and multiple logistic regression models to test associations between demographic characteristics and bacterial carriage or to test bacterial coexistence. All the analyses were conducted in SPSS version 17.0, with a two-tailed p < 0.05 as significant difference. Missing data were not included in the analyses. Statistical estimates were reported after adjusting for confounders.

Results

The study participants represented 32.5 % (1,088/3,348) of all children attending 6 kindergartens in 3 cities (6 districts): Shantou (Jinping [42.7 %, 167/391], Chenghai [33.3 %, 202/607], Chaoyang [32.7 %, 180/551], and Longhu [24.6 %, 150/610]), Jieyang (Rongcheng [35.1 %, 196/558]), and Chaozhou (Xiangqiao [30.6 %, 193/631]), or 0.8 % (1,088/0.14 million) and 0.3 % (1,088/0.4 million) of all kindergarten children in the 6 districts and in Chaoshan region, respectively.

Among the children, 79.6 % (866/1,088) were target-bacterial carriers, of which 34.4 % (298/866) were positive for ≥2 bacterial spp. (Table 1). The overall carriage of target bacteria was significantly lower in the oldest age group (5 ~ 6 years) compared to that in the youngest age group (2 ~ <3 years) (OR: 0.3, 95 % CI: 0.2–0.5, p < 0.05), and higher in the children from Chaozhou than in those from Shantou (OR: 2.5, 95 % CI: 1.5–4.0, p < 0.05, Table 1). The children who were older or who had parents with higher education were less likely to carry multiple bacteria (all p < 0.05, Table 1).

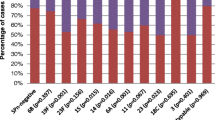

The most common pathogen among the bacterial carriers was M. catarrhalis (76.6 %, 663/866), followed by S. pneumoniae (26.6 %, 230/866), S. aureus (21.8 %, 189/866), H. parainfluenzae (12.7 %, 110/866), and H. influenzae (2.3 %, 20/866). Single or multiple bacterial carriages decreased with increasing age, except S. aureus carriage that increased with age (Figure 1).

Bacterial carriage in healthy kindergarten children by age group (n = 1,088). The cardinal numbers in the first column indicate the no. of bacterial species carried by individual children. Carriage of 4 bacterial species accounted for 0.7 % and 0.8 % of children in the 3 ~ <4 years- and 4 ~ <5 years-age groups, respectively (not shown in figure)

Multiple logistic regression analyses (Table 2) showed negative associations between age and the overall carriage (β: −0.3, aOR: 0.8, 95 % CI: 0.7–0.9, p < 0.001) or multiple carriage (β: −0.2, aOR: 0.8, 95 % CI: 0.7–0.9, p < 0.01) of bacteria, and between the father’s education level and multiple bacterial carriage (β: −1.1, aOR: 0.3, 95 % CI: 0.2–0.5, p < 0.0001). Age was negatively associated with the carriage of M. catarrhalis (β: −0.4, aOR: 0.7, 95 % CI: 0.6–0.8, p < 0.0001) and S. pneumoniae (β: −0.4, aOR: 0.7, 95 % CI: 0.6–0.8, p < 0.0001), but positively associated with the S. aureus carriage (β: 0.4, aOR: 1.5, 95 % CI: 1.3–1.7, p < 0.0001, data not shown). Risk of carrying target bacteria was higher among the children in Chaozhou than in Shantou (β: 1.1, aOR: 2.9, 95 % CI: 1.7–4.8, p < 0.0001).

Multiple logistic regression analyses (Table 3) showed that M. catarrhalis was positively associated with S. pneumoniae but negatively with S. aureus; S. pneumoniae was positively associated with M. catarrhalis and H. parainfluenzae but negatively with S. aureus; S. aureus was negatively associated with M. catarrhalis, S. pneumoniae, and H. parainfluenzae; H. parainfluenzae was positively associated with S. pneumoniae but negatively with S. aureus (all p < 0.05).

Discussion

This is the first study demonstrating a high frequency of carriage (79.6 %) of common pathogenic bacteria among healthy kindergarten children in Chaoshan region, southern China.

Nasal carriage rates of bacterial pathogens in healthy preschool or kindergarten children vary widely with studies and geographies. The global carriage rates of M. catarrhalis (16–67 %) [15–19], S. pneumoniae (10–69 %) [9, 15, 17, 19, 20], and S. aureus (10–50 %) [15, 17, 19, 21] are similar to the corresponding rates as 60.9 % (663/1,088), 21.1 % (230/1,088), and 17.3 % (189/1,088) in this study. However, the carriage rates of H. parainfluenzae (10.1 %, 110/1,088) and H. influenzae (1.8 %, 20/1,088) in this study are respectively much lower than 50.5–86.7 % in other studies from China [15, 21] and 10–83 % globally [15–17, 19]. Previous consumption of antibiotics or Hib vaccination could be the reasons for such low carriage although we could not verify this from incomplete information returned by the parents/guardians.

Predominant bacterial pathogens colonizing in healthy preschool children also differ geographically, with the most prevalent pathogen being M. catarrhalis in the present study (60.9 %) and Korea (35 %) [20], S. pneumoniae in the Czech Republic (38.1 %) [17], H. parainfluenzae in southern China (50.5 %) [21] and southwest China (86.7 %) [15], and H. influenzae in Belgium (83 %) [19]. The carriage of M. catarrhalis, S. pneumoniae, or H. influenzae is generally higher in the low income countries than that in the low-middle income countries [9], whereas the carriage of S. aureus is higher in the developed countries than in the developing countries [22].

Similar to our finding (34.4 %), multiple bacterial carriage, which can potentially lead to severe, life-threatening diseases [7, 9], is also common in healthy preschool/kindergarten children globally, for example, 19.8 % in the Czech Republic [17], 31.5 % in Korea [20], and 60.7 % in Belgium [19].

The carriage of these bacteria appears to fluctuate in a dynamic process throughout the host’s lifetime [6, 7, 20], with preschool period considered susceptible to infections due to insufficient innate immunity and close peer contact. Colonization and transmission of bacterial pathogens can be influenced by complex interplay of various factors, such as age, prior respiratory infection, antimicrobial use, and hygiene [7, 9].

In general, the carriage of bacterial pathogens decreases with age [6, 7, 9], with M. catarrhalis and S. pneumoniae in this study as an example. The colonization of M. catarrhalis, S. pneumoniae, and H. influenzae is higher in preschool children than in school children [20], or in children than in adults [9, 23]. In contrast, the carriage of S. aureus increases with age, as seen in this study and in Korea [20].

Although respiratory viral infections and/or antimicrobial consumption can precede bacterial colonization [7, 9, 19], no significant association was observed in this study and other studies as well [24–26].

The education levels of fathers and mothers were strongly correlated in this study (r = 0.7, p < 0.01 by Spearman’s correlation coefficient, a non-adjusted bivariate correlational analysis, data not shown); in multiple logistic regression models, the education level of fathers (not the mothers) had a positive relationship with multiple bacterial carriage in their children (Table 2), suggestive of better hygiene knowledge from higher education in those families. Poor hygienic conditions could also explain higher risk of bacterial carriage in the Chaozhou kindergarten in this study.

As observed in this study, coexistence or lack of coexistence of certain bacterial pathogens in nasal cavity have been reported in different countries [19, 20, 27, 28]. Particular attention should be paid to the coexistence because of its potential risk of infections, as exemplified by the reports that there are strong relationships between the colonization of M. catarrhalis, S. pneumoniae, and/or nontypable H. influenzae and otitis media [29, 30]. Screening pathogens in nasal microbiota and observing unwanted outcomes longitudinally may therefore be important in understanding the etiologic role of colonized pathogens.

Kindergartens, a place with risk of infection transmission, are highly regulated in many countries. Chinese kindergartens, including those in this study, are not satisfactory as to the infection control standards, such as lack of physical examination, crowded conditions, limited hygiene knowledge, and improper hygiene practices of staff and children, which are reflected by high isolation rates of bacterial pathogens from the hands of staff and children, inanimate surfaces, and toys [31–33]. The children carrying pathogenic bacteria are a potential source of drug-resistant pathogens, especially in face of prevailing antimicrobial overuse or misuse in Chinese pediatric population [34, 35]. Given carrying bacterial pathogens as a prelude of RTIs and potential of microbial transmission under poor hygienic conditions in crowded kindergartens, the study children are at high risk of RTIs.

There were limitations in this study. Health status of the participants was based on their past medical history provided in the questionnaire. Children and kindergartens in this study represented a relatively small proportion of those in the Chaoshan region. Therefore, our results should be interpreted cautiously. Intrinsic to cross-sectional study design, true cause and effect relationships between bacterial carriage and the factors investigated could not be established. Further studies are needed to understand the influence of bacterial carriages and disease occurrence.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates high nasal carriage of common pathogenic bacteria and coexistence of multiple pathogens in healthy kindergarten children in the Chaoshan region of southern China, with M. catarrhalis as the commonest colonizer. Increasing age of children and higher paternal education are associated with lower risk of bacterial carriage. Longitudinal follow-up studies would be required for better understanding the infection risk in bacterial pathogen carriers.

References

O'Brien KL, Wolfson LJ, Watt JP, Henkle E, Deloria-Knoll M, McCall N, Lee E, Mulholland K, Levine OS, Cherian T, et al. Burden of disease caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae in children younger than 5 years: global estimates. Lancet. 2009;374(9693):893–902.

World Health O. WHO position paper on Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccines. (Replaces WHO position paper on Hib vaccines previously published in the Weekly Epidemiological Record). Releve epidemiologique hebdomadaire/Section d'hygiene du Secretariat de la Societe des Nations = Weekly epidemiological record/Health Section of the Secretariat of the League of Nations. 2006;81(47):445–52.

Biedenbach DJ, Jones RN, Pfaller MA, Sentry Participants G. Activity of BMS284756 against 2,681 recent clinical isolates of Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis: Report from The SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (2000) in Europe, Canada and the United States. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2001;39(4):245–50.

Johnson DM, Sader HS, Fritsche TR, Biedenbach DJ, Jones RN. Susceptibility trends of haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis against orally administered antimicrobial agents: five-year report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;47(1):373–6.

Waters D, Jawad I, Ahmad A, Luksic I, Nair H, Zgaga L, Theodoratou E, Rudan I, Zaidi AK, Campbell H. Aetiology of community-acquired neonatal sepsis in low and middle income countries. Journal of global health. 2011;1(2):154–70.

Wertheim HF, Melles DC, Vos MC, van Leeuwen W, van Belkum A, Verbrugh HA, Nouwen JL. The role of nasal carriage in Staphylococcus aureus infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5(12):751–62.

Garcia-Rodriguez JA, Fresnadillo Martinez MJ. Dynamics of nasopharyngeal colonization by potential respiratory pathogens. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002;50(Suppl S2):59–73.

Diavatopoulos DA, Short KR, Price JT, Wilksch JJ, Brown LE, Briles DE, Strugnell RA, Wijburg OL. Influenza A virus facilitates Streptococcus pneumoniae transmission and disease. FASEB Journal: Official Publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2010;24(6):1789–98.

Adegbola RA, DeAntonio R, Hill PC, Roca A, Usuf E, Hoet B, Greenwood BM. Carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae and other respiratory bacterial pathogens in low and lower-middle income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e103293.

Leach AJ, Boswell JB, Asche V, Nienhuys TG, Mathews JD. Bacterial colonization of the nasopharynx predicts very early onset and persistence of otitis media in Australian aboriginal infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994;13(11):983–9.

Chaozhou Annual Statistical Report [http://www.gdcztjj.gov.cn/tjwj/tjnj/]. Accessed 29 Sept 2016.

2012 Shantou Annual Statistical Report [http://sttj.shantou.gov.cn/tjsj/tjnj/tjnj2012/]. Accessed 29 Sept 2016.

2012 Jieyang Annual Statistical Report [http://www.gdjystats.gov.cn/Article/ShowInfo.asp?ID=6394]. Accessed 29 Sept 2016.

WHO guidelines for the collection of human specimens for laboratory diagnosis of avian influenza infection [http://www.who.int/influenza/human_animal_interface/virology_laboratories_and_vaccines/guidelines_collection_h5n1_humans/en/]. Accessed 29 Sept 2016.

Liu L, Xie W, Jing C. Survey of respiratory tract microbial population in children. Chinese Journal of Microecology. 2007;19(1):22–6.

Naaber P, Tamm E, Putsepp A, Koljalg S, Maimets M. Nasopharyngeal carriage and antibacterial susceptibility of Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis in Estonian children. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2000;6(12):675–7.

Zemlickova H, Urbaskova P, Adamkova V, Motlova J, Lebedova V, Prochazka B. Characteristics of Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis and Staphylococcus aureus isolated from the nasopharynx of healthy children attending day-care centres in the Czech Republic. Epidemiol Infect. 2006;134(6):1179–87.

Quinones D, Llanes R, Torano G, Perez M. Nasopharyngeal colonization by Moraxella catarrhalis and study of antimicrobial susceptibility in healthy children from Cuban day-care centers. Arch Med Res. 2005;36(1):80–2.

Jourdain S, Smeesters PR, Denis O, Dramaix M, Sputael V, Malaviolle X, Van Melderen L, Vergison A. Differences in nasopharyngeal bacterial carriage in preschool children from different socio-economic origins. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17(6):907–14.

Bae S, Yu JY, Lee K, Lee S, Park B, Kang Y. Nasal colonization by four potential respiratory bacteria in healthy children attending kindergarten or elementary school in Seoul, Korea. J Med Microbiol. 2012;61(Pt 5):678–85.

Luo X, Liang J, Gao S, Li Z, Zhou R. Surveys on bacteria nasopharyngeal carriage prevalence in 186 children. Chinese Journal of Microecology. 2006;18(3):204–8.

Sivaraman K, Venkataraman N, Cole AM. Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage and its contributing factors. Future Microbiol. 2009;4(8):999–1008.

Obaro S, Adegbola R. The pneumococcus: carriage, disease and conjugate vaccines. J Med Microbiol. 2002;51(2):98–104.

Fontanals D, Bou R, Pons I, Sanfeliu I, Dominguez A, Pineda V, Renau J, Munoz C, Latorre C, Sanchez F. Prevalence of Haemophilus influenzae carriers in the Catalan preschool population. Working Group on Invasive Disease Caused by Haemophilus influenzae. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases: Official Publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology. 2000;19(4):301–4.

Ho PL, Chiu SS, Chan MY, Gan Y, Chow KH, Lai EL, Lau YL. Molecular epidemiology and nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant S. aureus among young children attending day care centers and kindergartens in Hong Kong. J Infect. 2012;64(5):500–6.

Thummeepak R, Leerach N, Kunthalert D, Tangchaisuriya U, Thanwisai A, Sitthisak S. High prevalence of multi-drug resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae among healthy children in Thailand. J Infect Public Health. 2015;8(3):274–81.

Jacoby P, Watson K, Bowman J, Taylor A, Riley TV, Smith DW, Lehmann D, Kalgoorlie Otitis Media Research Project T. Modelling the co-occurrence of Streptococcus pneumoniae with other bacterial and viral pathogens in the upper respiratory tract. Vaccine. 2007;25(13):2458–64.

Kwambana BA, Barer MR, Bottomley C, Adegbola RA, Antonio M. Early acquisition and high nasopharyngeal co-colonisation by Streptococcus pneumoniae and three respiratory pathogens amongst Gambian new-borns and infants. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:175.

Syrjanen RK, Auranen KJ, Leino TM, Kilpi TM, Makela PH. Pneumococcal acute otitis media in relation to pneumococcal nasopharyngeal carriage. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24(9):801–6.

Faden H, Duffy L, Wasielewski R, Wolf J, Krystofik D, Tung Y. Relationship between nasopharyngeal colonization and the development of otitis media in children. Tonawanda/Williamsville Pediatrics. J Infect Dis. 1997;175(6):1440–5.

Han J, Lin J, Lin L, Zou Q. Monitoring of disinfection quality in kindergartens of Guangdong province. Chinese Journal of Disinfection. 2009;26(4):414–6.

Huang J, Jiang S, Xie G, Chen H, Li X. The monitoring results of disinfection quality in kindergartens, Shantou in 2003–2005. South China J Prev Med. 2007;33(1):69–70.

Ma H, Zheng Z, Yang S. Investigation on disinfection quality of 81 kindergartens in Wolong district, Nanyang City. J Med Theor & Prac. 2012;25(10):1254–5.

Yang YH, Fu SG, Peng H, Shen AD, Yue SJ, Go YF, Yuan L, Jiang ZF. Abuse of antibiotics in China and its potential interference in determining the etiology of pediatric bacterial diseases. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1993;12(12):986–8.

Liang X, Jin C, Wang L, Wei L, Tomson G, Rehnberg C, Wahlstrom R, Petzold M. Unnecessary use of antibiotics for inpatient children with pneumonia in two counties of rural China. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011;33(5):750–4.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Frieda Law and Jiyan Zheng from Shantou University Medical College (SUMC) for facilitating this study, SUMC students (Lin Zhang, Jun Zeng, Jiangtao Sheng, Jinghua Su, and Fan Zhang) for assistance with sample collection, and the directors, staff, children and their parents/guardians of the study kindergartens for their participation.

Funding

This study was supported by Shantou University Medical College and the Li Ka Shing Foundation-University of Oxford Global Health Programme (grant No. B9RSRT0-14). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, interpretation of data, decision to publish, or writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and material

The data from the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

BLC designed and performed the experiments, and analyzed the data. HP analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. YCH trained BLC and technically facilitated the study. JCY performed the experiment. WB-T designed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shantou University Medical College and the Oxford University Tropical Research Ethical Committee (OxTREC). Written informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardians of children before enrollment.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Questionnaire. A questionnaire used for demographic/medical data collection from the kindergarten children and their parents/guardians. (DOCX 20 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Pan, H., Cui, B., Huang, Y. et al. Nasal carriage of common bacterial pathogens among healthy kindergarten children in Chaoshan region, southern China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr 16, 161 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-016-0703-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-016-0703-x