Abstract

Background

Visual disturbances associated with isolated sphenoid sinus inflammatory diseases (ISSIDs) are easily misdiagnosed due to the nonspecific symptoms and undetectable anatomical location. The main objective of this retrospective case series is to investigate the clinical features of visual disturbances secondary to ISSIDs.

Methods

Clinical data of 23 patients with unilateral or bilateral visual disturbances secondary to ISSIDs from 2004 to 2014 with new symptoms were collected. Collected data including symptoms, signs, neuroimaging and pathologic diagnosis were analyzed.

Results

There were 14 males and 9 females, and their ages ranged from 31 to 83 years. Fifteen patients suffered blurred vision and 11 patients suffered binocular double vision, including 3 patients who had unilateral visual changes and diplopia simultaneously. Headache was observed in 18 patients, and orbit pain/ocular pain in 8 patients. Other presenting symptoms included ptosis (4 patients) and proptosis (1 patient). Only 5 patients had nasal complaints. The corrected visual acuities were between NLP to 20/20. Patients with diplopia included 5 with unilateral oculomotor nerve palsy and 6 with unilateral abducens nerve palsy. All patients performed orbital/sinus/brain radiologic examination and found responsible lesions in sphenoid sinus. All patients underwent endoscopic sinus surgery, and 9 patients were found to suffer sphenoid mucocele, 9 with fungal sinusitis, and 5 with sphenoid sinusitis. Visual disturbances improved in 6 patients, and all the patients with diplopia had a postoperative recovery.

Conclusion

Visual disturbances resulting from ISSIDs are relatively uncommon, but it is crucial that the patient with new vision loss or diplopia and persistent headache or orbit pain be evaluated for the possibility of ISSIDs especially before corticosteroid administration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Isolated sphenoid sinus inflammatory diseases (ISSIDs) describe a collection of several pathologic entities, including sphenoid sinusitis (in which the majority is acute and bacterial sinusitis), sphenoid sinus mucocele, and chronic/ acute fungal infection. The sphenoid sinus lies in close proximity to important anatomic structures, [1] including the cavernous sinus, the optic nerve, the internal carotid artery, and cranial nerves III, IV, V, and VI. Thus, spread of infection or inflammation beyond the sphenoid sinus to these neighboring structures may result in serious intracranial and orbital complications and potentially irreversible or fatal neurological sequelae. The mortality is as high as 40%-80% in acute fungal sinusitis patients with orbit or intracranial invasion [2, 3]. However, the early symptoms of sphenoid sinus diseases are often nonspecific, and routine examinations offer little diagnostic information on sphenoid pathology, resulting in inappropriately delayed diagnosis and treatment. About 24%-50% patients with ISSIDs may present with decreased vision [4] and failure to consider sphenoid sinus disease as a possible cause may lead to delayed diagnosis. It should be noted that sphenoid disease in the presence of other sinus disease can also cause visual symptoms and needs to be addressed just as urgently, but it’s an another entity and will not be discussed here. Ophthalmologists thus have a very important role in detecting and diagnosing ISSIDs. Therefore, we retrospectively investigated the clinical features of the visual disturbances secondary to ISSIDs.

Methods

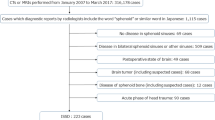

A retrospective electronic medical records review was performed on all patients who visited initially to the Ophthalmology Department and then were treated by the Otolaryngology Department of Beijing Tongren Hospital, from January, 2004 to November, 2014. Approval from Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of Capital Medical University for retrospective studies was obtained before commencing the study. The study followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Only patients who had presenting symptoms of decreased vision and/or double vision and diagnosed as isolated sphenoid sinus disease were selected. Generally, the patients had CT/ MRI of orbit/ sinus/ head examinations performed when the ophthalmologists tried to discover the cause of diplopia and/or optic neuropathy which was thought to be responsible for decreased vision based on the clinical picture. When sphenoid sinus lesions were noted on radiographic imaging, patients were referred to Otolaryngology Department because visual disturbances were thought to be related to the sphenoid sinus lesions. Each patient underwent endoscopic surgery as a principal treatment, and postoperative management included antimicrobial treatment, regular debridement and endoscopic examination. All specimens suggested isolated disease of sphenoid sinus. The diagnosis of isolated sphenoid sinus disease was made by otolaryngologists based on characteristic signs and symptoms, routine ear, nose, and throat examinations, radiographic imaging (CT or MRI), and histopathological examinations of the resected specimens. Exclusionary criteria were patients who had sinusitis of other paranasal sinuses or pathology arising from other sinuses and spreading into the sphenoid sinus, patients with malignant tumors, and patients had other ophthalmic or systemic disorders that were the cause of their visual symptoms. Demographic data, clinical symptoms, interval between the onset of visual disturbances and operation, physical signs, imaging studies (CT/ MRI of orbit/ sinus/ head), surgical findings, pathological reports and initial ophthalmic diagnosis were analyzed. Patients with incomplete or unavailable medical records were excluded.

Results

Among 67 patients who presented with symptoms of decreased vision and/or double vision and were diagnosed with isolated sphenoid sinus disease, 23 subjects were included in the present report (Table 1). Fourteen patients (61%) were male and 9 (39%) were female. Age ranged from 31 to 83 years old (mean 54.9 ± 15.8 years), with 10 patients (43%) older than 60 years of age. The interval, initial ophthalmic diagnosis, accompanying symptoms, radiologic findings, pathological diagnosis, and outcomes are summarized in Table 2. Table 3 shows the clinical manifestations in patients with fungal sphenoid sinusitis. The severity of visual loss secondary to isolated sphenoid sinus inflammatory lesions and fungal sphenoid sinusitis are shown respectively in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2.

The symptomatology was often nonspecific. The ocular symptoms occurred in the form of unilateral visual disturbance (blurred vision, 15/23), bilateral visual disturbance (binocular diplopia, 11/23), ptosis (4/23) and proptosis (1/23). Pain was the most frequent symptom, presenting in 20 (87%) of the 23 patients, including headache (18 patients) and ocular pain (8 patients). Specifically, there were 14 patients who suffered persistent and refractory headache since the onset of symptoms. Only 5 patients presented with nasal symptoms (including rhinorrhea, nasal obstruction and bloody rhinorrhea).

On initial examination, the population consisted of eight patients with unilateral optic neuropathy, one patient with bilateral optic neuropathy, four patients with unilateral optic neuritis, one patient with bilateral optic neuritis, one patient with unilateral optic nerve atrophy, five patients with unilateral incomplete oculomotor nerve palsy, four patients with unilateral incomplete abducens nerve palsy, and two with unilateral complete abducens nerve palsy. Among them, there were three patients had unilateral optic neuropathy and diplopia simultaneously.

Twenty-two subjects underwent CT/MRI scans of the orbits/sinuses/brain; imaging was interpreted as indicating fungal sinusitis in 4 cases, sphenoid sinus mucocele in 9 cases, and bacterial or inflammatory sphenoid sinusitis in 10 cases (Figs. 3, 4 and 5). All patients were treated by endoscopic sinus surgery to remove or drain the sphenoid sinus lesion, and the postoperative pathology was reviewed and compared with the preoperative radiologic diagnosis. The correct initial diagnosis was made in 18/23 (78.3%) cases (chronic fungal sphenoid sinusitis in 4 cases- case 10 and case 11, acute fungal sinusitis in 2 cases- case 3 and case 7, sphenoid sinusitis in 5 cases, mucocele in 9 cases), and the remaining 5 subjects had fungal sinusitis, all of whom were diagnosed preoperatively with nonspecific sphenoid sinusitis (cases 2, 13, 15 and 17 were finally diagnosed as chronic fungal sinusitis, and case 8 was diagnosed as acute fungal sinusitis).

Case 5, male, 51y, sphenoid sinus mucocele (right, VA = 30/200). Neuroimaging showed a hemispherical abnormal mass rose from right sphenoid sinus with expansion to surrounding areas. There is extension into the right orbital apex and compression of the right optic nerve. a: Axial CT scan showing the expansile lesion. b: Axial, T2-weighted MRI scans with homogenous, fluid density lesion in the right sphenoid sinus. c: Coronal CT scan shows chronic bony expansion of the sinus. d: Coronal, T1-weighted, contrast-enhanced MRI scan demonstrating the fluid-filled lesion

Neuroimaging for case 1, male, 47y, chronic sphenoid sinusitis (right, VA = 20/200). a: Axial computed tomography scan shows bony destruction at the right orbital apex. b: Axial, T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging scan reveals a homogenous, hyperintense lesion of the inferior aspect of the right sphenoid sinus. c: Coronal computed tomography scan demonstrating erosion of the bony medial orbital apex. d: Coronal, T1-weighted, contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging scan without contrast shows heterogenous signal in the right sphenoid sinus

Neuroimaging for case 3, female, 56y, invasive fungal sphenoid sinusitis (right, VA = no light perception). a: Axial CT scan with expansion and opacification of the right optic canal and optic nerve, which was invaded by fungal organisms. b: Axial, T2-weighted MRI scan showing hypointense signal primarily adjacent to the right optic canal. c: Coronal CT scan showing opacification of the right anterior clinoid process. d: Coronal, T2-weighted, contrast-enhanced MRI scan with abnormal signal in the area of the right orbital apex

All patients received additional medical treatments after surgery including antifungal drugs where indicated. Upon discharge, vision had improved in seven of the seventeen eyes (41.2%) with decreased visual acuity, including 3 eyes with fungal sphenoid sinusitis; 2 of these 3 had a short duration of vision loss (6 and 20 days), and the third had good initial visual acuity (VA = 20/30) despite 1-year disease duration preoperatively (case 11). The remaining 4 eyes (case 5, 9, 12), with vision loss from mucocele, regained vision as well. Three of the 4 eyes (cases 9, 12) had a short duration of 3 or 5 days (cases 9 and 12), while case 5 had only moderately (20/60) preoperative visual loss. All patients with diplopia had improvement but the degree of recovery was variable.

Discussion

Optic neuropathy from ISSIDs may arise from spread of sinus inflammation and infection, compression by an expansible lesion, or ischemia [5]. Visual loss may be acute or subacute, and the fundus often is normal or shows mild optic disc swelling, which might result in a misdiagnosis of “optic neuritis”. In the present series, patients who suffered vision loss without ptosis were all diagnosed as optic neuritis or optic neuropathy initially. The manifestations of optic neuropathy secondary to ISSIDs differ from the optic neuritis associated with multiple sclerosis (MS), also called typical optic neuritis (ON). Typical ON most commonly affects women less than 50 years old, and usually presents with subacute painful loss of vision in one eye. The pain usually localizes in or around one eye and commonly worsens with eye movements. The severity of the pain varies, but it is unusual for it to disturb sleep or last longer than a few days. Spontaneous recovery of vision begins within three to 5 weeks after onset, and systemic high-dose corticosteroid administration can hasten the recovery of visual acuity [6, 7]. In our study, all 15 patients with optic neuropathy from ISSIDs have no gender differences, in which the ratio of men and women almost equally divided. Patients suffered persistent headache, migraine, or pain around the eye. The visual acuity decreased progressively, showing no response to steroid therapy or only brief improvement. These characteristics fit atypical ON, which differs greatly from typical ON. For this entity, it is crucial to perform brain or orbital radiologic imaging and serum laboratory tests, especially before the use of systemic corticosteroids or immunosuppressive agents [8, 9]. In diagnosis of ISSIDs-associated optic neuropathy, the significance of the radiologic workup is far more important than serum laboratory tests. Adequate brain and/or orbital imaging were critical in making the diagnosis of ISSIDs in this series. It is notable that different pathogens of ISSIDs may have similar features on brain or orbital MRI. Five patients in our series interpreted as sphenoid sinusitis through brain or orbital MRI turned out to be fungal infection pathologically. It is commonly difficult to distinguish between fungal infection of sphenoid sinus and other sphenoid inflammation according to MRI features alone, but the former always causes bony changes [4, 10], thinning or thickening, which may be shown on CT. Mucoceles can cause bony loss via pressure/expansion. Therefore, sinus CT should be performed if brain or orbital MRI shows sphenoid sinusitis. If adjacent bony destruction is found on CT, infection by fungus or tumor formation should be highly suspected, and biopsy should be performed as soon as possible.

Sphenoidotomy with drainage is the main procedure to diagnose and treat the ISSIDs [11]. Treatment with steroids alone before clearing the infectious lesions may facilitate the spread of infection, especially in acute fungal infection, and may even result in life-threatening intracranial spread; therefore, steroid should only be used once the underlying infectious lesion has been excluded or treated. A small dose of steroid may be used postoperatively to reduce swelling if needed. In the present study, only 7/17 eyes experienced slight visual acuity improvement postoperatively, similar to previous reports [12, 13]. The poor prognosis of visual acuity in ISSIDs may result from the severe injury of optic nerve and the coexistence of multiple injury mechanisms including direct nerve infiltration by inflammation and infection, compression, and ischemia. Despite the limited efficacy of visual function in long duration cases of sinusitis by surgery, it remains important in preserving the retained visual function, improving or relieving headache, and preventing the further spread of infection or inflammation.

The binocular diplopia from ISSIDs arises with involvement of one or more cranial nerve(s) and/or extraocular muscles by infiltration or compression from the inflammatory lesion. In the 11 cases of binocular visual disturbance in the present study, 5 patients presented with incomplete unilateral oculomotor nerve palsy, 4 with incomplete unilateral abducens nerve palsy and 2 with complete unilateral abducens nerve palsy. Two of the five patients with incomplete unilateral oculomotor nerve palsy also had ipsilateral optic nerve injury due to the involvement of orbital apex and presented with incomplete orbital apex syndrome. In the other three subjects, injury of oculomotor nerve in the region of orbit, direct injury of extraocular muscles, or both may have led to double vision. For patients with abducens nerve palsy, we surmise that inflammation from the sphenoid sinus spread to the abducens nerve in cavernous sinus, where the abducens nerve runs close to the sphenoid sinus [14]. All the patients with diplopia in the present study had remarkable improvement of double vision after debridement of sinus lesions. Furthermore, the improvement in diplopia was much better than the improvement in visual acuity of optic nerve injury. It is possible that the ocular motor nerves are more likely to recover from this type of injury than is the optic nerve, and subjects with diplopia also may undergo neuroimaging earlier in their disease course than those patients with vision loss alone.

When presents as orbital apex syndrome, some important entities should be differentiated. Cavernous sinus thrombosis (CST) is a life-threatening disorder that can complicate facial infection, sinusitis, orbital cellulitis, especially in the setting of a thrombophilic disorder. Early signs of CST include fever, headache, and ophthalmic involvements, which are nearly universal, including periorbital edema, lid erythema, ptosis, proptosis, restricted or painful eye movement, and less commonly papilledema, decreased visual acuity [15]. High-resolution contrast-enhanced head CT typically shows cavernous sinus expansion and irregular filling defects as direct signs [16]. Tolosa-Hunt syndrome is another differential disease and is described as unilateral orbital pain associated with paresis of one or more of the III, IV and/or VI cranial nerves, which resolves spontaneously but may recur. Episodic orbital pain often localized around the ipsilateral brow and eye. Clinically, Paresis coincides with the onset of pain or follows it within 2 weeks and resolve within 72 h when treated adequately with corticosteroids [17]. Granulomatous inflammation of the cavernous sinus, superior orbital fissure or orbit, demonstrated by MRI or biopsy are important in differential diagnosis [18].

There are some limitations in this study. Firstly, there was not complete information about the exact visual acuity outcomes since the patients were discharged from the Department of ENT and did not have a later ophthalmologic examination. Prospective enrollment of patients with ISSIDs may allow us to identify factors that influence final visual outcome in the short and long-term, and we propose to evaluate such factors in future research.

Conclusion

In conclusion, although visual disturbances resulting from ISSIDs are relatively uncommon, it is important to understand the clinical features of visual disturbances secondary to ISSIDs to avoid the misdiagnosis and mistreatment. Whenever patients with manifestations of atypical optic neuritis, particularly those with severe or persistent headache and/or orbit pain, are evaluated, neuroimaging to include the orbits, sinuses, and brain must be performed expeditiously to allow identification of the underlying causes, especially before administration of systemic corticosteroids.

Abbreviations

- ISSIDs:

-

Isolated sphenoid sinus inflammatory diseases

- MS:

-

Multiple sclerosis

- ON:

-

Optic neuritis

References

JW-rd W, Kern EB, Djalilian M. Isolated sphenoid sinus lesions. Laryngoscope. 1973;83:1252–65.

Shamim MS, Siddiqui AA, Enam SA, Shah AA, Jooma R, Anwar S, et al. Craniocerebral aspergillosis in immunocompetent hosts: surgical perspective. Neurol India. 2007;55:274–81.

Hedges TR, Leung LS. Parasellar and orbital apex syndrome caused by aspergillosis. Neurology. 1976;26:117–20.

Wang ZM, Kanoh N, Dai CF, Kutler DI, Xu R, Chi FL, Tian X. Isolated sphenoid sinus disease: an analysis of 122 cases. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2002;111:323–7.

Lin Y, Fang S, Ho H. Isolated sphenoid sinus disease: analysis of 11 cases. Tzu Chi Medical Journal. 2009;3:227–32.

Rodriguez M, Siva A, Cross SA, O’Brien PC, Kurland LT. Optic neuritis: a population–based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Neurology. 1995;45:244–50.

Pula JH, Reder AT. Multiple sclerosis. Part I: neuro-ophthalmic manifestations. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2009;20:467–75.

Martinelli V, Marzoli SB. Non-demyelinating optic neuropathy: clinical entities. Neurol Sci. 2001;22:55–9.

Hoorbakht H, Bagherkashi F. Optic neuritis, its differential diagnosis and management. Open Ophthalmol J. 2012;6:65–72.

Krennmair G, Lenglinger F, Muller-Schelken H. Computed tomography (CT) in the diagnosis of sinus aspergillosis. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1994;22:120–5.

Nour YA, Al-Madani A, El-Daly A, Gaafar A. Isolated sphenoid sinus pathology: spectrum of diagnostic and treatment modalities. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2008;35:500–8.

Patt BS, Manning SC. Blindness resulting from orbital complications of sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;104:789–95.

Lee LA, Huang CC, Lee TJ. Prolonged visual disturbance secondary to isolated sphenoid sinus disease. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:986–90.

Chi SL, Bhatti MT. The diagnostic dilemma of neuro-imaging in acute isolated sixth nerve palsy. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2009;20:423–9.

Weerasinghe D, Lueck CJ. Septic cavernous sinus thrombosis: case report and review of the literature. Neuroophthalmology. 2016;40(6):263–76.

Lee JH, Lee HK, Park JK, Choi CG, Suh DC. Cavernous sinus syndrome: clinical features and differential diagnosis with MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:583–90.

Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia. 2013;33:629–808.

Schuknecht B, Sturm V, Huisman TA, Landau K. Tolosa-hunt syndrome: MR imaging features in 15 patients with 20 episodes of painful ophthalmoplegia. Eur J Radiol. 2009;69:445–53.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funds.

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are contained within the manuscript. All raw data used during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LC carried out the acquisition and analysis of data and drafting the manuscript. LJ made substantial contributions to conception and design of the study and revising the manuscript. YB and PS participated in analysis and interpretation of data. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of Capital Medical University.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients to publish their cases in this case series.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, L., Jiang, L., Yang, B. et al. Clinical features of visual disturbances secondary to isolated sphenoid sinus inflammatory diseases. BMC Ophthalmol 17, 237 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-017-0634-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-017-0634-9