Abstract

Introduction

Isolated sphenoidal sinusitis (ISS) is a rare disease with non-specific symptoms and a potential for complications. Diagnosis is made clinically, endoscopically, and with imaging like CT scans or MRIs. This study aimed to evaluate if ISS meets the EPOS 2020 criteria for diagnosing acute rhinosinusitis and if new diagnostic criteria are needed.

Materials and methods

The study analyzed 193 charts and examination records from 2000 to 2022 in patients diagnosed with isolated sphenoidal sinusitis at the Ziv Medical Center in Safed, Israel. Of the 193, 57 patients were excluded, and the remaining 136 patients were included in the final analysis. Patients were evaluated using Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT), neurological and sinonasal video endoscopy, radiological findings, demographic data, symptoms and signs, and laboratory results. All these findings were reviewed according to the EPOS 2020 acute sinusitis diagnosis criteria and were analyzed to determine if ISS symptoms and signs fulfilled them.

Results

The patients included 40 men and 96 women, ranging in age from 17 to 86 years (mean ± SD, 37 ± 15.2 years). A positive endoscopy and radiography were encountered in 29.4%, and headache was present in 98%; the most common type was retro-orbital headache (31%). The results showed that there is no relationship between the symptoms of isolated sphenoidal sinusitis and the criteria for diagnosing acute sinusitis according to EPOS 2020.

Conclusion

ISS is an uncommon entity encountered in clinical practice with non-specific symptoms and a potential for complications. Therefore, the condition must be kept in mind by clinicians, and prompt diagnosis and treatment must be initiated. This kind of sinusitis does not fulfill the standard guidelines for acute sinusitis diagnosis criteria.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Isolated sphenoidal sinusitis (ISS) is a relatively uncommon disease. Among patients with rhinosinusitis, isolated sphenoiditis is diagnosed in 1–3% of cases [1, 2].

According to the literature, the most common cause of sphenoid sinus lesions is inflammation, as found in up to 65%–72% of cases, followed secondly by neoplasms, which account for 18% (in benign) and 10.9% (in malignant) of the cases, respectively [3].

Because of its deep-seated anatomy, this sinus does not usually present with nasal symptoms such as nasal obstruction or rhinorrhea. The most common symptom is headache, which is prevalent in about 98% of inflammatory lesions [4].

In the majority of cases, symptoms do not arise in the early stages of the disease or are non-specific, and some cases may subsequently be referred to the otolaryngology department after significant progression of the disease [5]. Diagnosis is made clinically, endoscopically, and with the help of current imaging techniques such as CT scans or MRIs. All three previously mentioned modalities, especially endoscopic examination and imaging techniques, increased the likelihood of diagnosing such a disease. A computed tomographic scan (CT) is used as the first choice of investigation [6].

In the study by Berg and Carenfelt [7], the presence of two or more findings (purulent rhinorrhea and local pain with unilateral predominance, pus in the nasal cavity, and bilateral purulent rhinorrhea) showed 95% sensitivity and 77% specificity for the diagnosis of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis (ABRS). The estimated parameters of endoscopy are superior to those of radiography, with a sensitivity of 80% and a specificity of 94% [8].

Acute bacterial sinusitis is suspected in patients whose upper respiratory tract infection has persisted beyond 10–14 days. [9, 10]. Prominent symptoms in adults include nasal congestion, purulent rhinorrhea, facial-dental pain, postnasal drainage, headaches, and coughs [11]. Although all of these symptoms are non-specific [12, 13], a history of persistent purulent rhinorrhea and facial pain appears to have some correlation with an increased likelihood of bacterial disease. [14, 15]

The European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps 2020 (EPOS2020) is the latest in a series of evidence-based position papers that aim to provide clear evidence-based recommendations and integrated care pathways in ARS and CRS [16].

Acute rhinosinusitis (ARS): management as per EPOS 2020: Acute rhinosinusitis in adults is characterized by two or more symptoms, one of which should be either: nasal blockage, swelling, or congestion; nasal discharge (anterior or posterior nasal drip); ± facial pain or pressure; ± reduction or loss of smell (cough in children); and a duration of < 12 weeks [17] (Table 3).

Our study attempted to evaluate cases of isolated acute sphenoidal sinusitis over a 22-year period who were admitted to the Ziv Medical Center emergency department (ED).

The diagnosis was based on clinical features and CT findings with medical consensus.

The goal of this study is to describe the different features, the initial symptoms, and the common practice findings between both neurologists and otolaryngologists.

Our main questions were:

-

What are the clinical presentations and symptoms of acute isolated sphenoidal sinusitis?

-

Who was the first physician to examine the patient in the ED?

-

What are the common practice findings between both neurologists and otolaryngologists?

-

Does ISS meet the criteria of EPOS 2020 [17] for diagnosing acute rhinosinusitis? Analyzing retrospectively patients' symptoms and endoscopic findings with statistical analysis

-

Do we need new diagnostic criteria for this rare entity apart from the EPOS 2020 criteria?

This study is the first one in the literature to analyze such a diagnostic dilemma compared to the most updated evidence-based acute sinusitis diagnosis guidelines.

Materials and methods

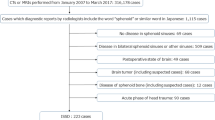

We analyzed 193 charts and examination records from 2000 to June 2022 in patients who were admitted to the ED and diagnosed with isolated sphenoidal sinusitis in Ziv Medical Center, Israel. Of the 193, 57 patients were excluded, and the remaining 136 patients were included in the study.

Our primary study inclusion criteria were collected according to: 1. Clinical presentation: For patients who presented to the ED with an acute ISS diagnosis involving only the unilateral sphenoid sinus, we reviewed patients’ complaints with detailed descriptions of headaches (type, severity, frequency, duration) and other presenting symptoms (nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, facial pain, loss of smell, cough, visual disturbances, etc.). 2. Radiologic findings (CT imaging): detailed assessment of sphenoid sinus opacity or abnormalities; documentation of any abnormality such as mucosal thickening, fluid accumulation, or bony erosion. 3. Endoscopic examination findings (such as the presence of pus, polyps, or mucosal abnormalities).

In each case, we evaluated the following:

1) Demographic data (age, gender, major diagnosis, medical history).

2) Patient symptoms and signs in the medical record: nasal blockage, obstruction, congestion or nasal discharge; anterior or posterior nasal drip; reduction or loss of sense of smell; fever > 38 °C; facial pain or pressure; headache type (frontal, retro-orbital, trigeminal, vertex, temporal, occipital); dizziness; blurred vision; syncope; etc. The data were collected by both the otolaryngologist and neurological documentation.

All these findings were reviewed according to EPOS 2020 diagnosis criteria and analyzed to see if the criteria were fulfilled.

3) Endoscopic signs of nasal polyps and/or mucopurulent discharge primarily from the superior meatus.

4) CT changes: mucosal thickness; the presence or absence of an air–fluid level and air bubbles in the isolated sphenoidal sinus; and whether the lesion was round or expansive, completely opaque, irregularly shaped, and showed calcification on CT and/or the flow void sign on MRI—if the patients completed an MRI scan. Based on imaging, we categorized the cases as follows: inflammation, fungal disease, mucocele, cysts, and unclassifiable.

5) Who was the first physician who examined the patient in the ED?

6) Neurological findings: physical examination, comparing the patient’s history with ENT history and combining these, pathological findings, and the patient's results if they underwent a lumbar puncture.

7) Laboratory results: leukocytes, CRP.

Patients were excluded from the study if: 1) they had ISS involving the bilateral sphenoid sinuses or other sinuses; 2) prior skull base surgery or transnasal pituitary surgery; 3) brain tumor (including suspected cases); 4) disease of the sphenoid bone (including suspected cases); 5) acute head trauma; 7) suspected chronic lesion; 8) patients who were treated in the first 10 days after symptom onset; or 9) if there was a lack of data or follow-up.

The patients who were excluded were: 8 patients had bilateral sphenoid sinuses; 2 had prior skull base surgery; 1 had a brain tumor; 4 had a disease of the sphenoid bone; 5 came with acute head trauma; 15 patients were treated in the first 10 days after symptom onset; and 11 had a lack of data or follow-up. Five patients were diagnosed with benign or malignant pathologies: four with fungal sinusitis and two with mucocele. We started the analysis with the ED's first visit.

Patients were evaluated in most cases first by objective neurological examination (headache as a major complaint), objective ear, nose, and throat examination, and by nasal-sinus video endoscopy, with or without radiological diagnosis in the ED. If the patient did not undergo CT, this was done after admission to the hospital department. At the time of the diagnosis, there was no involvement of other sinuses. The diagnosis was confirmed by CT of the paranasal sinuses and nasal cavities in axial and coronal sections, without contrast fluid.

In some cases, MRI was used when there was a neurological pathology, possible bone erosion of the sinus wall, the presence of a cerebrospinal fluid leak, and visual changes.

Patients were admitted mostly in the ENT department and sometimes in the neurology department because severe headaches were the major complaint and suspected meningitis had to be ruled out.

Admitted patients who were diagnosed with isolated sphenoiditis without complications were treated with intravenous antibiotics ceftriaxone and clindamycine for 3–6 days associated with corticosteroids. As mentioned above, admitted patients who were diagnosed with isolated sphenoiditis without complications were treated with intravenous antibiotics.

Only 3 patients were treated with endoscopic surgical procedures because of the worsening or maintenance of the severity of symptoms during the treatment or within 6 weeks after it.

Benign or malignant pathologies were excluded.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) version 21 (SPSS Inc.; Chicago, IL, USA). The data were described by the mean standard deviation (SD) and frequency. Normal and non-normal distribution variables were compared using a one-sample t-test. The normality of the variables was checked by the one-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test.

A one-sample t-test compares the mean of a sample to a population mean. When only a sample standard deviation is known, a t-test should be used. If the calculated t-value is less than the critical t-value, the null hypothesis (hypothesis of no difference) should not be rejected, with no significant difference between the sample mean and population mean declared. However, if the calculated t-value is larger than the critical t-value, the null hypothesis should be rejected, with a significant difference in means declared.

The null hypothesis (H0) and two-tailed alternative hypothesis (H1) of the one-sample T test can be expressed as:

H0: µ = µ0 ("the population mean is equal to the [proposed] population mean").

H1: µ ≠ µ0 ("the population mean is not equal to the [proposed] population mean").

where µ is the "true" population mean and µ0 is the proposed value of the population mean.

Results

There were 40 men and 96 women, ranging in age from 18 to 86 years (mean ± SD, 37 ± 15.2 years) (Table 1).

Symptoms lasted for a mean ± SD of 15.6 ± 9.3 days. Of the 136 patients, 34 were given antibiotics by the community physician before referral to the hospital.

Headache was the major complaint that presented in 98% of our series. Patients reported a major complaint of several types of headaches; the most common type was retro-orbital headache (31%), vertex headache (28%), and frontal headache (20%). 14 patients had postnasal drip (10%), 32 patients had nasal obstruction (23%), and 12 had fever (8%). There were 2 cases of a decrease in consciousness level (Table 2).

Positive endoscopy and radiography findings were found in 39 patients (29.4%). Video endoscopy of these patients revealed signs of inflammation, characterized by mucosal edema and mucopurulent discharge arising from the sphenoethmoidal recess.

Patients who presented with acute isolated sphenoidal sinusitis were classified into subgroups according to the diagnostic criteria of acute sinusitis based on EPOS 2020, which is known as the latest series of guidelines on rhinosinusitis from an international cohort of experts in the field (Table 3). If the p value is less than 0.05 and the difference is statistically significant, the null hypothesis is therefore rejected. This illustrates that there is no relationship between two variables: the symptoms of isolated sphenoidal sinusitis and the criteria for diagnosing acute sinusitis according to EPOS 2020 (Table 4). We also used Pearson’s r to measure the strength of the relationship between isolated sphenoidal sinusitis symptoms and the EPOS 2020 criteria, as shown in Table 5, which revealed that there is no correlation.

A lumbar puncture was performed in 23 patients to rule out meningitis; no one had meningitis in our series, and the results are shown in Table 6.

Discussion

Based on the results of this study and the literature, we recommend a new diagnostic strategy for patients with isolated unilateral acute sphenoidal sinusitis.

There is a lack of consensus on how we diagnose acute isolated sphenoidal sinusitis (AISS), with wide variation in diagnosis across guidelines. This lack of uniformity in disease definition stems in part from an incomplete understanding of disease pathobiology, phenotypic heterogeneity, and natural history.

Unlike other diseases, where definitions are centered around a specific diagnostic test, AISS is not only a clinical syndrome for which we rely on a constellation of symptoms, signs, and other manifestations. We also often need a radiological diagnosis combined with clinical features.

In this study, we reviewed gaps between guidelines and existing diagnostic tools. Ebell et al. concluded in a meta-analysis [20] that acute rhinosinusitis as diagnosed by any reference standard is significantly less likely in patients without any nasal discharge, without a complaint of purulent nasal discharge, and with normal transillumination. According to our results, this conclusion does not include isolated sphenoidal sinusitis.

In another study by Berg and Carenfelt [21], the presence of two or more findings (purulent rhinorrhea and local pain with unilateral predominance, pus in the nasal cavity, and bilateral purulent rhinorrhea) showed 95% sensitivity and 77% specificity for the diagnosis of ABRS.

Inflammatory sinusopathy does not mean an infectious presentation; that is, we should also consider the viral infection in the first days of the disease. To classify acute rhinosinusitis, we should take into consideration the duration of the symptoms, so in this study, all the patients who had symptoms before 10 days of treatment were excluded. According to EPOS 2012, 2020, [17 and 22], acute bacterial rhinosinusitis is classified as having symptoms lasting longer than 10 days.

The diagnosis of acute rhinosinusitis is mainly clinical. In the practice of medicine, it refers to the clinical presentation of a particular patient at a time when an accurate and correct diagnosis may be difficult to make.

In the clinical evaluation of a patient with a diagnostic dilemma, a physician has at his or her disposal numerous diagnostic technologies, including laboratory tests, imaging, and even interventional procedures.

Lew et al. [23]reported 30 patients with infectious sphenoid sinusitis (15 acute cases, 15 chronic cases). The main symptom of their patients was a headache that radiated to the occipital region or pain in the trigeminal nerve distribution. Similar to our results, the authors agreed that CT was the most useful method for the diagnosis of sphenoid sinus disease.

After reviewing 122 individuals, Fooanant et al. [24]came to the conclusion that sphenoid sinus illness could not be completely ruled out by a routine endoscopic examination. The most prevalent pathology across all investigations was infection or inflammation. The majority of investigations found that bacterial sphenoiditis was the most prevalent lesion in this group. Because of its high intensity and intractability, the attending physicians asked for imaging tests such as a brain CT scan. Headaches were the most prevalent symptom in their study, appearing in 63% of participants.

The sphenoid sinus is uncommonly involved solely by inflammatory disease and tumors [25]. Lew et al. [23] suggested an incidence of 2.7% for isolated sphenoid disease; however, Hnatuk et al. [26] estimated it to be less than 1% of all sinus disease.

Epos 2020 defined the alarm symptoms as follows: periorbital edema or erythema; displaced globe; double vision; ophthalmoplegia; reduced visual acuity; severe headache; frontal swelling; signs of sepsis; signs of meningitis; and neurological signs requiring an immediate referral.

The main limitation of the study is to consider only isolated bacterial sinusitis. This model is not applicable to other types of sphenoiditis.

The study’s strengths are that it describes a rare cause of sinusitis that was identified by a multidisciplinary team, including neurologists with lumbar puncture results for the first time in the literature, in addition to otolaryngologists findings, and that there was a lengthy follow-up of those patients following treatment. Finally, it can help to develop a new method for identifying this uncommon type of sinusitis, particularly since it does not fit the guidelines for acute sinusitis diagnosis.

Conclusion

ISSD is an uncommon entity in clinical practice with non-specific symptoms and a potential for complications. The most common symptom is headache. The neurologist may be the first doctor to check patients in the emergency department. Therefore, the condition must be kept in mind by clinicians, prompt diagnosis with an otolaryngologist must be made, and treatment must be initiated. This kind of sinusitis does not fulfill the standard guidelines for acute sinusitis diagnosis criteria. For the diagnosis of ISS, we advise creating a chain of diagnostic algorithms. Adhering to such a protocol can help patients and doctors feel more secure about the diagnosis and treatment strategy while also being cost-effective and requiring fewer invasive procedures.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [RF], upon reasonable request.

References

Cheung DK, Martin GF, Rees J (1992) Surgical approaches to the sphenoid sinus. J Otolaryngol 21:1–8

Lew D, Southwick FS, Montgomery WW et al (1983) Sphenoid sinusitis: a review of 30 cases. N Engl J Med 309:1149–1154

Knisely A, Holmes T, Barham H, Sacks R, Harvey R (2017) Isolated sphenoid sinus opacification: a systematic review. Am J Otolaryngol 38(2):237–243

Grillone P (2004) Kasznica, “Isolated sphenoid sinus disease.” Otolaryngol Clin N Am 37(2):435–451

Sieskiewicz A et al (2011) Isolated sphenoid sinus pathologies—the problem of delayed diagnosis. Med Sci Monit 17:180–184

Martin TJ, Smith TL, Smith MM, Loehrl TA (2002) Evaluation and surgical management of isolated sphenoid sinus disease. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 128(12):1413–1419

Berg O, Carenfelt C (1988) Analysis of symptoms and clinical signs in the maxillary sinus empyema. Acta Otolaryngol 105:343–349

Berger G, Steinberg D, Popovtzer A, Ophir D (2004) Endoscopy versus radiography for the diagnosis of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 262(5):416–422. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-004-0830-0

Hickner JM, Bertlett J, Besoler RE et al (2001) Principles of appropriate antibiotic use for acute sinusitis in adults: background position paper American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine. Ann Intern Med 134:498–505

Gadosnaki AM (1993) Potential interventions for preventing pneumonia among young children: lack of effect of antibiotic treatment for upper respiratory infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J 12:115–120

Lindbaek M, Hjortdahl P (2002) The clinical diagnosis of acute purulent sinusitis in general practice—a review. Br J Gen Pract 52:491–495

Lacroix JS, Ricchetti A, Lew D et al (2002) Symptoms and clinical and radiological signs predict the presence of pathogenic bacteria in acute rhinosinusitis. Acta Otolaryngol 122:192–196

Druce HM (1992) Diagnosis of sinusitis in adults: history, physical examination, nasal cytology, echo, and rhinoscope. J Allergy Clin Immunol 90:436–441

Ray DA (2001) Rohren CH Characteristics of patients with upper respiratory tract infections presenting to a walk-in clinic. Mayo Clin Proc 76:169–173

Alho OP, Ylitalo K, Jokinen K et al (2001) The common cold in patients with a history of recurrent sinusitis: increased symptoms and radiologic sinusitis-like findings. J Fam Pract 50:26–31

Fokkens W, Desrosiers M, Harvey R, Hopkins C, Mullol J, Philpott C, et al. EPOS2020: development strategy and goals for the latest European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis Rhinology. 2019;57(3):162–8.

Fokkens W.J., Lund V.J., Hopkins C., Hellings P.W., Kern R. et al.: European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps, Rhinology, 2020; 58(Suppl S29): 1–464. https://doi.org/10.4193/Rhin20.600.

Ebell, M. H., McKay, B., Guilbault, R., & Ermias, Y. (2016). Diagnosis of acute rhinosinusitis in primary care: A systematic review of test accuracy British Journal of General Practice, 66 (650). https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp16x686581

Khalid OM, Omer MB, Kardman SE et al (2022) A prospective study of acute sinusitis, clinical features, and modalities of management in adults in Sudan Egypt. J Otolaryngol 38:129. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43163-022-00316-9

Ebell MH, McKay B, Dale A, Guilbault R, Ermias Y (2019) Accuracy of signs and symptoms for the diagnosis of acute rhinosinusitis and acute bacterial rhinosinusitis The. Ann Fam Med 17(2):164–172. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2354

Spector SL, Bernstein IL, Li JT, Berger WE, Kaliner MA, Schuller DE et al (1998) Parameters for the diagnosis and management of sinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 102:S107–S144

Fokkens WJ, Lund VJ, Mullol J, Bachert C, Alobid I, Baroody F et al (2012) European position paper on rhinosinusitis 4 and nasal polyps, 2012. Rhinol Suppl 23:1–298

Lew D, Southwick FS, Montgomery WW, Weber AL, and Baker AS (1983) Sphenoid sinusitis. A review of 30 cases New Eng J Med 309: 1149–1154.

Fooanant, S., Angkurawaranon, S., Angkurawaranon, C., Roongrotwattanasiri, K., & Chaiyasate, S. (2017). Sphenoid Sinus Diseases: A Review of 1,442 Patients International Journal of Otolaryngology, 2017, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/9650910

Barrs DM, McDonald TJ, Whisant JP (1992) Metastatic tumors in the sphenoid sinus. Laryngoscope 89:1239–1243

Hnatuk LA, Macdonald RE, Papsin BC (1994) Isolated sphenoid sinusitis: the Toronto Hospital for Sick Children experience and review of the literature. J Otolaryngol 23:36–41

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the entire department of Otolaryngology head and neck surgery for their help and support.

Funding

We have nothing to disclose and no financial disclosures.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Raed Farhat, Ashraf Khater, Shlomo Merchavy. Data curation: Raed Farhat, Aviva Ron, Yaniv Avraham, Nidal El Khatib, Formal analysis: Raed Farhat, Majd Asakly. Investigation: Raed Farhat, Shlomo Merchavy, Saqr Massoud, Alaa Safia, Marwan Karam, Ashraf Khater. Methodology: Shlomo Merchavy, Yaniv Avraham, Saqr Massoud, Supervision: Shlomo Merchavy, Aviva Ron. Validation: Shlomo Merchavy. Visualization: Raed Farhat, Shlomo Merchavy, Writing—original draft: Raed Farhat, Shlomo Merchavy, Yaniv Avraham. Writing—review and editing: Raed Farhat, Shlomo Merchavy, Aviva Ron.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

We have nothing to disclose and no financial disclosures.

Ethical committee

The study was approved by the Ziv Medical Center human ethics Helsinki committee.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Farhat, R., Khater, A., Khatib, N.E. et al. Does acute isolated sphenoidal sinusitis meet the criteria of the recent acute sinusitis guidelines, EPOS2020?. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 281, 2421–2428 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-023-08405-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-023-08405-y