Abstract

Background

Breast cancer is the most common type of cancer in women worldwide. Though improved treatments and prolonged overall survival, breast cancer survivors (BCSs) persistently suffer from various unmet supportive care needs (USCNs) throughout the disease. This scoping review aims to synthesize current literature regarding USCNs among BCSs.

Methods

This study followed a scoping review framework. Articles were retrieved from Cochrane Library, PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Medline from inception through June 2023, as well as reference lists of relevant literature. Peer-reviewed journal articles were included if USCNs among BCSs were reported. Inclusion/exclusion criteria were adopted to screen articles’ titles and abstracts as well as to entirely assess any potentially pertinent records by two independent researchers. Methodological quality was independently appraised following Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal tools. Content analytic approach and meta-analysis were performed for qualitative and quantitative studies respectively. Results were reported according to the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews.

Results

A total of 10,574 records were retrieved and 77 studies were included finally. The overall risk of bias was low to moderate. The self-made questionnaire was the most used instrument, followed by The Short-form Supportive Care Needs Survey questionnaire (SCNS-SF34). A total of 16 domains of USCNs were finally identified. Social support (74%), daily activity (54%), sexual/intimacy (52%), fear of cancer recurrence/ spreading (50%), and information support (45%) were the top unmet supportive care needs. Information needs and psychological/emotional needs appeared most frequently. The USCNs was found to be significantly associated with demographic factors, disease factors, and psychological factors.

Conclusion

BCSs are experiencing a large number of USCNs in fearing of cancer recurrence, daily activity, sexual/intimacy, psychology and information, with proportions ranging from 45% to 74%. Substantial heterogeneity in study populations and assessment tools was observed. There is a need for further research to identify a standard evaluation tool targeted to USCNs on BCSs. Effective interventions based on guidelines should be formulated and conducted to decrease USCNs among BCSs in the future.

Highlights

-

A total of 16 domains of USCNs were finally identified.

-

Social support, fear of cancer recurrence, and daily activity were the top unmet supportive care needs among breast cancer survivors. Information needs and psychological needs were reported frequently.

-

Unmet supportive care needs were significantly affected by demographic factors, disease factors, and psychological factors.

-

Substantial heterogeneity in study populations and assessment was observed. Assessment tools that specifically to unmet supportive care needs in breast cancer survivors were absent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer is a global cause for concern owing to its high incidence among women around the world [1]. According to the Global Cancer Statistics 2020 [2], female breast cancer has surpassed lung cancer as the most commonly diagnosed cancer, with an estimated 2.3 million new cases (11.7%). With improvements in early detection, surgery, and adjuvant therapy for breast cancer, long-term survival and cure are becoming possible. It is estimated that currently, 5-year survival rates are in the range of 90%, and 10-year survival is about 80% [3]. Quality of life is thus becoming a major issue for these patients. Nevertheless, many of them continue to be burdened by psychological distress and poor quality of life throughout their cancer trajectory [4]. Postoperative complications and side effects of chemoradiotherapy leave serious impacts on multiple aspects of their life, resulting in fatigue, sleep disorder, limb dysfunction [5], and even severe psychological matters [6]. Some recent studies unveiled that BCSs has endorsed moderate to high levels of depressive symptoms, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress [7]. Therefore, they report increased supportive care needs that require high-quality care in the domains of psychosocial, informational, and relational perspective [8, 9].

Supportive care encompasses a person-centered approach to care that aims to help a person with cancer and their family to meet their needs at multiple levels, from pre-diagnosis through the process of diagnosis and treatment to cure, continuing illness or death and into bereavement [10, 11]. The term “supportive care needs” is an umbrella term covering the physical, informational, emotional, practical, social, and spiritual needs of a person affected by cancer [12].

To ensure patients’ needs are addressed, there has been an increasing interest in supportive care needs assessment. Needs that were not well addressed and where additional support was required were classified as ‘unmet needs’ [11]. There is a growing body of literature that recognizes the significance of unmet supportive care needs (USCNs) among BCSs [13,14,15]. In the healthcare field, USCN reflects incongruity between the supports that an individual perceives to be necessary versus the actual supports provided [16]. It can be seen as covering a spectrum of healthcare needs that are not optimally met [17]. USCNs assessment is a patient‐oriented approach, which can lead resources to be distributed efficiently, and bring better outcomes for patients as finite medical resources could be directed to the benefit of patients with the greatest needs [18]. The ultimate goal is increasingly aligned and predictable pathway for the management and assessment, to meet the most required supportive care needs.

There is increasing evidence that USCNs can have a detrimental effect on BCSs’ well-being [19]. Accurate identification of USCNs of BCSs not only increases their satisfaction, but also improve their quality of life [20, 21]. Nevertheless, the knowledge about the most primary USCNs breast cancer patients are facing remains inadequate and unclear. Systematic reviews regarding USCNs were performed in some cancer groups, such as advanced cancer patients and their caregivers [22], prostate cancer patients [23], lung cancer [24], bladder cancer [25], and head and neck cancer [26]. Despite much observational study has been conducted, limited research has focused on any systematic review into USCNs among BCSs. A comprehensive understanding of USCNs among BCSs is crucial to direct future research and clinical practice. Therefore, a cohesive and up-to-date synthesis of the literature is needed to describe the USCNs of BCSs, which can inform the design and delivery of quality supportive care for this growing and diverse subpopulation, as well as guiding thinking to shape effective, evidence-based interventions. The main objective of this systematic scoping review is to identify, analyze and synthesize existing literature regarding the USCNs among BCSs and organize them into a structure from which the reader can obtain an in-depth understanding of this topic.

Methods

Review framework

This study employed a scoping review methodology to examine the range and scope of the available literature on the investigated topic, producing a rigorous synthesis and disseminating the existing evidence to date. The scoping review followed a methodological framework including the following five-stage process [27]: identifying the research question; identifying relevant studies; study selection; charting the data; and collating, summarizing, and reporting the results.

This review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [28]. The protocol was registered in PROSPERO with a registration number of CRD42022360528.

Review questions

-

1.

What are the USCNs of BCSs?

-

2.

How many categories of domains of USCNs can be divided?

-

3.

Which USCNs accounts the most proportion among BCSs?

-

4.

What are the factors that might influence the USCNs?

Search strategy

An extensive search strategy was conducted in Cochrane Library, PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Medline from inception through June 2023. Medical subject headings (MeSH) and text words were used to identify studies. The search strategy for ‘unmet supportive care need’ was Search #1: “needs assessment” [MeSH Terms] OR “needs assessment” [Title/Abstract] OR “assessment of healthcare needs” [Title/Abstract] OR “assessment of health care needs” [Title/ Abstract] OR “unmet needs” [Title/Abstract] OR “supportive care” [Title/Abstract] OR “need” [Title/Abstract]. The search strategy for ‘breast cancer survivor’ was Search #2: "breast neoplasms"[MeSH Terms] OR “breast neoplasms” [Title/Abstract] OR “breast cancer” [Title/Abstract] OR “breast tumor” [Title/Abstract] OR “breast oncology” [Title/Abstract]. An extended range search was carried out through ‘Search #1’ And ‘Search #2’. Furthermore, a snowballing strategy was also used with reference lists of relevant literature to locate additional studies not identified in the search strategies.

Eligibility criteria

Participants criteria

According to the definition of the National Cancer Institute (NCI), survivor signifies one who remains alive and continues to function during and after overcoming a serious hardship or life-threatening disease. In cancer, a person is considered to be a survivor from the time of diagnosis until the end of life. It can be extended that breast cancer survivors refer to breast cancer individuals from the time of breast cancer diagnosis through the process of their lifespan. Thus, breast cancer survivors and breast cancer patients were both regarded as survivors in the present study. The criteria for participants were determined based on this premise: adult survivors (≥ 18 years) who were diagnosed with breast cancer, regardless of cancer stage, and current treatment, were eligible.

Studies

Studies investigating USCNs of BCSs were included. The eligibility criteria for selecting studies are listed as follows:

Inclusion criteria

-

• Any study published in a peer-reviewed journal of qualitative or quantitative design.

-

• English articles were included only to obtain articles with enough authoritativeness and professionalism, as well as to avoid language barriers and translation bias.

-

• USCNs were reported as primary or secondary outcomes (or expressed in terms of an unresolved desire for support/service provision/concerns that are explicitly referred to and measured as ‘unmet needs’).

Exclusion Criteria

-

• Conference articles, abstracts, editorial comments, guidelines, or unpublished works.

-

• Any study that included a mixed population, the results were reported together and could not be separated for breast cancer.

-

• The reported outcome from patients in the terminal or end-of-life care phase (final weeks/days of life).

-

• Any study solely focused on the presence of quality of life, satisfaction, or some specific unmet need (such as unmet symptoms/ psychology problems/ reproductive concerns/ rehabilitation/ diet and so on).

Quality assessment

For each included study, methodological quality was independently appraised by two authors following Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal checklist, which was recommended for studies reporting prevalence data and also suitable for qualitative studies [29]. It aims to assess the methodological quality of studies and to determine the extent to which a study has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct, and analysis. When disagreement occurred, a consensus was reached by discussion. The JBI critical appraisal checklist for qualitative research and prevalence research could be divided into 10 and 9 measurement properties, respectively. As for mixed studies, we used both tools for each part. For the qualitative part, JBI critical appraisal checklist for qualitative research was used. For the quantitative part, JBI critical appraisal checklist for studies reporting prevalence data was applied. Each question option can be rated as “yes”, “no”, “unclear”, or “not applicable”. In each item, the percentage of each option was calculated and multiplied by 100%. The higher ‘yes’ responses on the appraisal items indicated a study of superior quality. The risk of bias scores was categorized based on “yes” rates as ≥ 80% (low), 60 to 80% (moderate), and < 60% (high).

Study selection and data extraction

Two independent researchers performed double-checks on literature screening and data extracting. In an initial round of screening, study authors reviewed the titles and abstracts in the consolidated dataset for relevance based on the abovementioned inclusion/exclusion criteria. In a secondary screening, articles were reviewed in their entirety and incorporated into the present review if they met the eligibility criteria. Disagreements were addressed via frequent discussions with a third independent author or between the authors. A final set of articles fitting the scope of the present review were analyzed and summarized. A pre-defined Excel form was formulated specifically for this review to facilitate the extraction of pertinent data. The columns of the characteristics of the included studies were designed and the key information relevant to the review question were recorded. Essential information was extracted from eligible articles involving title, authors, country of origin, year of publication, sample size, population demographics, research design, assessment tools, main finding, the proportion of unmet needs, and factors related to USCNs. Whereby studies measured USCNs at multiple time points, all data corresponding to the different time points were extracted. However, only baseline measures were used for data synthesis in tables and figures.

Data analysis and synthesis

For qualitative studies, the content analytic approach was applied to narrative synthesis. For quantitative studies that reported the prevalence of USCNs, total participants, domain categories and proportion were recorded and calculated. If there was any study that reported two or more USCNs with varying proportions in a given domain, the median proportion was calculated (i.e., if a study reported multiple items in the domain of unmet psychological need, such as stress, anxiety, and depression with different proportions, the median proportion was calculated to represent the whole rate of the domain). The larger median proportion indicates a higher USCN.

The meta-analysis was performed using Review Manager Software (version 5.3). The pooled proportions (with respective 95% CIs) for each domain were calculated. To explore heterogeneity between the studies the I2 statistics were used. Given the heterogeneity of estimates, a random-effects model was set. When I2 was > 0.50% the statistical heterogeneity was considered substantial. We limited meta-analysis to quantitative studies that applied comprehensive (multiple domains) needs assessments: This was to ensure some comparability between pooled studies, and to avoid inflation of estimates that may arise from targeted assessment in a single domain. Tables and bar charts will be used to present the main results.

Results

Literature search

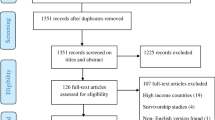

A total of 10,574 records were retrieved. After excluding 2803 duplicates, a total of 7771 studies were retrieved for titles and abstracts screening. After screening for titles and abstracts, 7471 articles were excluded and 300 papers were retrieved for full-text review. The final 77 articles were included, which consisted of 21 qualitative studies, 52 quantitative studies, and 4 mixed studies. The flow chart of the literature search is shown in Fig. 1.

Quality assessment

The overall risk of bias is shown in Figs. 2 and 3. More than 6o% of the quantitative studies had ‘Yes’ responses to all nine items. Nearly 34.5% had ‘No’ responses to the “Condition was measured in a standard, reliable way for all participants” item and “Valid methods were used for the identification of the condition” item. A few studies had “Unclear” responses on the “Study subjects and the setting were described in detail” item (about 25.6%). Among qualitative studies, nearly 60% of articles had “No” responses to the “Is there a statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically?” item. Nearly 29% of articles had “Unclear” responses to the “Is the influence of the researcher on the research, and vice-versa, addressed?” item, and 67% had “No” responses to the “Is there a statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically?” item.

Literature characteristics

The final 77 articles were included, which consisted of 52 quantitative studies, 21 qualitative studies, and 4 mixed studies [30,31,32]. For mixed studies, the quantitative part was assigned as the quantitative study, and qualitative part was assigned as the qualitative study. Therefore, there are 56 quantitative studies and 25 qualitative studies that were included in the final analysis. The literature characteristics were summarized in Table 1. The publication period is from 2004 to 2023. There were 33 (42.9%) studies that are published after 2018. The United States, China, Korea, Australia, and the UK published the most articles. Most quantitative studies were cross-sectional design. The most used instrument was the self-made questionnaire (19, 33.9%) [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50], followed by The Short-form Supportive Care Needs Survey questionnaire (SCNS-SF34) (12, 23.2%) [31, 51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63], Supportive Care Needs Survey (5, 8.9%) (SCNS) [64,65,66,67,68], Cancer Survivors Unmet Needs (3, 5.4%) (CaSUN) [19, 69, 70] and The Comprehensive Needs Assessment Tool (2, 3.6%) (CNAT) [30, 71]. In-depth, semi-structured interview was the most used approach in qualitative studies. The majority of the participants included in this review were women diagnosed with breast cancer who were in the post-treatment period. Only five studies involved objects who were undergoing treatment. There were 16 domains of USCN were finally identified, they were: physical/symptom need, psychological/emotional need, fear of cancer recurrence/ spreading, family support, medical support, social support, financial support, sexual/intimacy need, coping/survival need, daily activity need, spiritual support, information support, medical counseling, peer communication, cognitive needs, and dignity.

The estimated prevalence of USCNs from quantitative studies

The quantitative synthesis evaluating the proportion of USCNs in each domain were listed in Table 2. The most proportion of USCN was focused on social support (74%), daily activity (54%), sexual/intimacy (52%), fear of cancer recurrence/ spreading (50%), and information support (45%). However, the point estimate for social support should be interpreted with enough caution for they were extracted from two studies, which were highly inconsistent in their estimates [90.9% versus 52%]). The pooled estimate was based on a small sample, and the heterogeneity was large (I2 = 100%). There were amounts of studies that were excluded without the full text, which also may be one source of risk of bias.

Frequency of unmet needs

By calculating the frequency of unmet domains (Fig. 4), information need (55) and psychological/emotional need (52) were been found to appear most frequently, followed by physical/symptom (43) medical support (35), and fear of cancer recurrence/ spreading (32).

Frequency of unmet needs. PS: Physical/symptom; PE: Psychosocial/emotional; FCR: Fear of cancer recurrence/ spreading; FS: Family support; MS: Medical support; SS: Social support; Fns: Financial support; Sex: sexual/intimacy; Cop: Coping/survival; Act: Daily activity; SP: Spiritual support; Inf: Information support; MC: Medical counseling; PC: Peers communication; Cog: Cognitive needs; Dig: Dignity

Prominent needs lists of each domain

The prominent needs with the median proportion of each domain were listed in Table 3. In physical/symptom domain, the frequently reported needs were lack of energy/tiredness [53.6% (10.6%-88.8%)], fatigue [51% (23%-87.7%)], pain [45.5% (18.5%-66%)], sleep disorder [44.9% (14%-57%)], and hot flashes [43% (23%-100%)]. In the psychosocial/emotional domain, the frequently reported needs were learning to feel in control of your situation [58.2% (47.9%-64.1%)], worrying that the results of treatment are beyond your control [54% (16.7%-71.8%)], concerns about the worries of those close to you [51.2% (43.4%-97.8%)], keep a positive outlook [49% (37%-53.8%)], and anxiety [48.7% (16%-90.6%)]. Fears of cancer spreading [57.5% (16.4%-80.3%)] and fear of cancer recurrence [47.9% (28.6%-73%)] play the predominant part in the fear of cancer recurrence/ spreading domain. Help to know how to support my family/ partner was the greatest USCN (85.2%) in family-related support. In the medical support field, the frequent USCNs were ongoing medical service [63%(37.4%-74.5%)], nutritional/diet needs [58%(28.4%-74)], wished to be able to obtain medical service in a quick and easy way when in need [50.9%(43.7%-85.5%)], reassurance by medical staff that the way you feel is normal [39.8% (30.8%-43%)], and hospital staff acknowledging, showing sensitivity to your feeling and emotion needs [38% (28.2%-48.8%)]. Help to handle the topic of cancer in social/work situations [53.5%(50.4%-90.9%)] was the highest USCN in social support. Diminished sexual activity/sexual drive was unveiled to be the prime unmet need in the interpersonal/intimacy/sexual support field. In survival/coping needs help to make new relationships (94%), dealing with my belief that nothing bad will happen again (85.2%), and dealing with the impact of cancer on my relationships (84.6%) were the prominent USCNs. Exercise need was the most mentioned in daily activity. Help with my spiritual beliefs counted 66%(40%-92%) in spiritual need. In health system/information, up to date understandable information about your cancer and treatment [62.5%(31.4%-89.5%)], being informed about cancer which is under control or diminishing (i.e., remission) [54.1%(20.8%-76.5%)], information related to hereditary of disease [52.5%(52.1%-52.9%)], and being informed about things you can do to help yourself to get well [51%(14.9%-80.9)] were the most pointed unmet needs. To have one member of the hospital staff with whom you can talk to about all aspects of your condition, treatment, and follow-up [45.5%(34.9%-87.7%)], spent time for discussing disease [45.3%(31.8%-63.2%)], and having access to professional counseling (e.g., psychologist, social worker, counselor, nurse specialist) if you, family, or friends need it [43.9%(27.7%-82%)] were mainly indicated in medical counseling. Talk to others who have been through a similar experience counted the most [40.4%(29.6%-87%)] in peers’ communication. Cognitive needs counted 37.8% [37.8%(36%-39.5%)]. Help to adjust to changes to the way I feel about my body (82.1%) was the primary issue in dignity needs.

Synthesis of unmet needs in qualitative studies

A content analytic approach was conducted to synthesize USCNs and categorize them into different domains. The result of the synthesis was listed in Table 4. In family support, participants not only expressed the need for support from family members but also presented the need in supporting their family members, which was in agreement with the result from quantitative research. In dignity, except for an unmet need in body image, more needs regarding disease disclosure were also expressed.

Risk factors related to unmet needs

It was found that USCNs were significantly associated with many factors such as age, education, symptoms, treatment, stress, anxiety, and so on (Table 5), which could be summarized into three main aspects: demographic factors, disease factors, and psychological factors. Variables significantly associated with higher USCNs across all domains (psychological, health system and information, physical and daily living, patient care and support, and sexual) were indeterminate in age, marriage, occupational status, family income, level of education, and treatment time. The determinable single relationship was discovered in rural residents, short duration, combined treatment, advanced disease stage, poor performance status, higher depression, higher stress, higher distress, higher anxiety, poor QoL, symptoms severity, more comorbidity, and physical impairment.

Discussion

From the cancer genomic revolution, and new inroads in immunotherapy for breast cancer to unique concerns of quality of life as well as survivors’ issues, these works represent much of the promise of breast cancer research as well as the challenges in the coming years [107]. There is a huge burden of supportive care needs among BCSs that are still under management, such as psychosocial issues [108], sexuality [109], information [110], and symptoms burden [111]. Most authors have investigated the USCNs among BCSs [112, 113] through cross-sectional study or qualitative interview. However, to our knowledge, few researchers conducted evidence synthesis [23, 114]. This scoping review aimed to explore the breadth and depth of existing literature on USCNs among BCSs, with the goal of obtaining an in-depth understanding of this topic. Overall, this scoping review identified 77 primary studies evidencing the USCNs of breast cancer survivors. The aims are trying to inform the prominent needs as well as influence factors, to provide guidelines for conveying superior cancer care.

Quality appraisal

The results of the quality assessment of the involved research were presented in Figs. 2 and 3. The overall studies demonstrated a low to moderate risk of bias. It showed sufficient quality in terms of research method, data collection, and analysis. For quantitative research, there was an overall low risk of bias in sample size and appropriate sample frame. However, a high risk of bias was found in the detailed description of the study subjects and setting (44.2%), and how the participants were sampled (42%). The most used instrument was the self-made questionnaire and measurement heterogeneity were due to the use of unvalidated instruments. In the qualitative studies, the overall low risk of bias was found in conclusion drawing, ethical reporting, and representativeness of data. However, a high risk of bias was related to missing statements locating the researcher culturally or theoretically (79%), and the absence of stated philosophical perspective (54%).

Assessment of USCNs

Many instruments are available to assess USCNs in breast cancer survivors. The most used instrument was the self-made questionnaire. Substantial heterogeneity was existing in their categories, development, and quality. The Short-form Supportive Care Needs Survey questionnaire (SCNS-SF34) was widely used in evaluating the need for supportive care among cancer patients with verified validity and reliability [115, 116]. However, the standardized assessment tools that are specific to people with breast cancer and their unique USCNs are absent. In our review, only Supportive Care Needs Survey-Breast Cancer (SCNS-Breast) [15] and Cancer Survivor Profile-Breast Cancer (CSP-BC) [73] were designed specifically for breast cancer patients. Meanwhile, few instruments covered all of the measurement properties [117]. Various unmet needs evaluation tools become problematic as domains assessed in our review often include psychological aspects, patient care and support, physical aspects and daily living, health system information, and sexuality [118], resulting in spiritual, social, and concerns for family or financial needs were under revealed. Besides, under most circumstances, the methodological quality was variable. In addition, dimension classifications of USCNs differ between instruments, which complicates comparisons within the literature. An urgent demand for a more specific instrument with universal applicability for BCSs should be emphasized. Meanwhile, qualitative research had provided some points that quantitative studies did not obtain. Compared to the fixed items, qualitative research provides a more flexible approach to expressing subjective experiences. Thus, the results of qualitative studies should serve as a meaningful reference for the construction and development of more specific evaluation tools.

Prevalence of USCNs

Through making a comprehensive analysis of literature and summarizing them, 16 domains of USCNs were finally identified: physical/symptom need, psychological/emotional need, fear of cancer recurrence/ spreading, family support, medical support, social support, financial support, sexual/intimacy need, coping/survival need, daily activity need, spiritual support, information support, medical counseling, peer communication, cognitive needs, and dignity. This classification is more detailed, specific, and diversified than most previous studies [118,119,120], which could be helpful in clearly figuring out the definite unmet needs. In addition, extra USCNs were observed in concerns on caregiver burnout through qualitative studies, which indicated a need for appropriate support for their family/ caregiver/ partners. By estimating the pooled prevalence of USCNs from quantitative studies, it was found that social support (74%) counted the most proportion. However, with a small number of studies and large heterogeneity, caution must be applied as the findings might not be applicable to most breast cancer survivors. Even so, social support is still an indispensable part of BCSs. It was suggested that social support was significantly associated with resilience, posttraumatic growth [121], quality of life [122] and affective-cognitive symptoms [123]. Some social determinants such as poverty, lack of education, neighborhood disadvantage, racial discrimination, lack of social support, and social isolation were proven to significantly affect breast cancer incidence, stage at diagnosis, and survival [124]. In the present study, breast cancer patients commonly face unmet needs regarding social support in “help to handle the topic of cancer in social/work situation”, “a culture that discourages the discussion of cancer or culturally appropriate cancer resources”, “strong social support networks”, “social difficulties”. In the dignity domain, disease disclosure was also conveyed. It could be speculated that BCSs require adequate social support to in favor of their discussion and expression of the disease.

Daily activity (54%), sexual/intimacy (52%), fear of cancer recurrence/ spreading (50%), and information support (45%) were regarded as the top USCNs with high estimated prevalence. Information needs, psychological/emotional needs, physical/ symptom, medical support, and fear of cancer recurrence/spreading were been found to appear most frequently. In conclusion, fear of cancer recurrence/spreading and information need was the most reported with high pooled proportion and reporting frequency. Similarly, some previous studies have demonstrated that addressing recurrence concerns (80%) was the most commonly required [125]. Hypermutation occurs in 5% of all breast cancers with enrichment in metastatic tumors [126]. Fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) could be a powerful determinant of physical symptoms [127], psychological distress [128] and quality of life [129]. Our study demonstrated that BCSs not only faced the huge USCNs in FCR regarding “fears cancer spreading/recurrence”, but also in “dealing with the impact that having a faulty gene has had on your family”. It is not strange that the FCR is similarly reflected in the high information need related to hereditary disease. Psychological interventions might be an effective solution. A recent systematic review has recommended mindfulness and acceptance therapy-based interventions and short-term interventions to alleviate FCR [130]. Interventions to alleviate excessive worries and enhance feelings of personal control might help prevent or reduce related FCR [131].

Information needs were proved to be the most important concern among the diverse USCNs of cancer survivors [113]. Among BCSs, anxiety related to inadequate information support is common. A recent systematic review revealed that patients with breast cancer showed a huge enthusiasm in engaging intervention related to disease-focused information [132]. The prominent needs in the information domain vary among diverse patient groups. Patients with hematological malignancies were found to be mostly concerned about obtaining information about their future condition [9]. Meanwhile, more information about diet/nutrition in the form of a pamphlet or by a hospital dietician, and more information about the long-term self-management of symptoms and complications at home were discovered in patients with colon and/or rectum cancer [10]. A systematic review and synthesis of breast cancer patients' information needs developed a thorough information need model, including 3 themes, 19 categories, and 55 concepts [133]. In the present scoping review, “up to date understandable information about cancer and treatment”, “being informed about cancer which is under control or diminishing (i.e., remission)”, and “information related to hereditary disease” were the most stressed information need. Information needs regarding survivorship education, self-management, lifestyle advice and available access to healthcare sources, and choice of cancer specialists were also expressed. It inspired us to give more consideration in incorporating these unmet information needs into health education practice when delivering care for patients with breast cancer. It is believed information provision on BCSs could improve quality of life, reduce anxiety and increase intention to adhere to treatment recommendations [134]. American Society of Clinical Oncology Breast Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline has recommended that primary care clinicians should assess the information needs of breast cancer patients and its treatment, adverse effects, other health concerns, and available support services, and should provide or refer survivors to appropriate resources to meet these needs [135]. Technology-based or web-based seems to be an effective approach to provide enough information aid [136, 137]. Bootsma et al. integrated their investigation results about unmet information needs into a user-centered design to develop an informative website that targeted men with breast cancer [13].

Sexuality and intimacy represent a pillar of quality of life. The vast amount of evidence exists showing that cancer dramatically impacts a woman’s sexuality, sexual functioning, intimate relationships, and sense of self [138]. The overall prevalence of sexual dysfunction among female cancer survivors ranged from 16.7 to 67% [139]. Currently, sexual trouble is becoming more prevalent in BCSs owing to breast absence led by surgical treatment, body image, and adjuvant hormones. Low sexual desire persists throughout the timeline of BCSs, from BC diagnosis to after treatment [140]. Patients suffer from hot flashes, difficulty sleeping, loss of libido and intimacy, all resulting in significant morbidity and loss of quality of life [141]. The current finding exhibited that BCSs faced a majority of unsolved sexuality issues, particularly in diminished sexual activity/sexual drive, changes in sexual relationships and sexual feelings. A similar study conducted in gynecological cancer survivors revealed that they faced most sexual concerns on decreased sexual activity, emotional distancing from the partner, anxiety, and depression related to sexual performance [142, 143]. Among female cancer survivors, dyspareunia was the main type of sexual dysfunction reported after diagnosis [139]. Although, sexual issues are often neglected and not appropriately addressed by healthcare providers in their routine practice, which remains an unmet need with remarkable effects on general health and quality of life [144]. Effective communication between the health care professionals and cancer survivors was recommended to overcome this problem [139]. A review of the literature revealed trends utilizing psychoeducational interventions that include combined elements of cognitive and behavioral therapy with education and mindfulness training, which has positive effects on arousal, orgasm, satisfaction, overall well-being, and decreased depression [141].

Factors associated with USCNs

Our present review showed that USCNs were significantly associated with demographic data, social determinants, disease status, quality of life, performance status, and some psychological indicators. However, causality cannot be determined due to the cross-sectional nature of the included studies. Meanwhile, due to the heterogeneity of research design, participation, and setting, a positive predictor in one article may be negative in another. Short duration since diagnosis, advanced disease stage, poor performance status, higher depression, higher stress, higher distress, anxiety, poor quality of life, more symptoms severity, existing comorbidity, and physical impairment, were identified to be significantly associated with higher USCNs of nearly all domains in most research. Compared to longer duration, a short duration since diagnosis might means more inadaptation no matter in physical or psychological or other aspects. As many studies had showed [70, 145, 146], high psychological issues, physical status, and poor quality of life were the strong predictive factors of high USCNs in BCSs. Patients who are assessed as high-risk need should be paid more attention in practice. Hence, the implementation of standardized screening tools in any phase of disease trajectory should be conducted for timely identification and intervention. In addition, prospective studies are needed to verify influencing factors that have a causal relationship with USCNs.

Limitations and future directions

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first and most comprehensive systematic scoping review regarding USCNs among breast cancer survivors. Firstly, through making a comprehensive analysis of literature and summarizing, a total of 16 domains of USCNs were finally identified. This classification is more detailed, specific, and diversified than most previous studies. Secondly, the most unmet supportive care needs were identified and the prominent needs lists of each domain were exhibited meticulously with proportion, through which the reader could obtain an in-depth understanding of USCNs among the breast cancer population. Thirdly, a comprehensive vision was provided to know potential influencing factors to USCNs for most of them were presented synthetically.

Even though, our study has some limitations. One of the limitations is the inclusion of literatures that are published only in English. In addition, there were amounts of studies without the full text. These may result in the exclusion of potentially useful research. What’s more, we failed to perform subgroup analysis because of the complexity and heterogeneity of the incorporated breast cancer population.

Research about USCNs among BCSs in more detailed classifications are needed to provide targeted supportive care, there is a need for more comparations among breast cancer patients in different subgroups. Also, an urgent demand for a more specific instrument with universal applicability for BCSs should be emphasized due to the heterogeneity of assessment tools. What’s more, we summarized the risk factors of unmet needs but failed to analyze the odds ratio (OR), hazard ratios (HRs), or relative risk (RR) of each variable. Data synthesis through meta-analysis or prospective study to determine the real factors are demanded.

Conclusion

BCSs are experiencing the highest USCNs in fear of cancer recurrence, daily activity, sexual/intimacy, psychology, and information field. Various risk factors had been discovered to correlate with USCNs. Factors that have a causal relationship with USCNs should be identified through synthesizing longitudinal studies. There was substantial heterogeneity in study populations and assessment methods warranting future investigation considering specific samples and standard USCNs assessment tools that are validated for use in BCSs. Meanwhile, effective interventions based on guidelines should be formulated and conducted to decrease USCNs among BCSs in the future.

Availability of data and materials

All data relevant to the study are included in the article. All the raw data analyzed during this study could be obtained through contacting the first author.

References

Kashyap D, Pal D, Sharma R, Garg VK, Goel N, Koundal D, Zaguia A, Koundal S, Belay A. Global increase in breast cancer incidence: risk factors and preventive measures. Biomed Res Int. 2022;2022:9605439.

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: Cancer J Clin 2021;71(3):209–249.

Nardin S, Mora E, Varughese FM, D’Avanzo F, Vachanaram AR, Rossi V, Saggia C, Rubinelli S, Gennari A. Breast cancer survivorship, quality of life, and late toxicities. Front Oncol. 2020;10:864.

Grusdat NP, Stäuber A, Tolkmitt M, Schnabel J, Schubotz B, Wright PR, Schulz H. Routine cancer treatments and their impact on physical function, symptoms of cancer-related fatigue, anxiety, and depression. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30(5):3733–44.

Shamieh O, Alarjeh G, Li H, Abu Naser M, Abu Farsakh F, Abdel-Razeq R, et al. Care needs and symptoms burden of breast cancer patients in Jordan: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(17):10787.

Lovelace DL, McDaniel LR, Golden D. Long-term effects of breast cancer surgery, treatment, and survivor care. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2019;64(6):713–24.

Roziner I, Perry S, Dahabre R, Bentley G, Kelada L, Poikonen-Saksela P, et al. Psychological and somatic symptoms among breast cancer patients in four European countries: a cross-lagged panel model. Stress Health. 2022;39(2):474–82.

Tsai W, Nusrath S, Zhu R. Systematic review of depressive, anxiety and post-traumatic stress symptoms among Asian American breast cancer survivors. BMJ Open. 2020;10(9):e037078.

Tsatsou I, Konstantinidis T, Kalemikerakis I, Adamakidou T, Vlachou E, Govina O. Unmet supportive care needs of patients with hematological malignancies: a systematic review. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2021;8(1):5–17.

Kotronoulas G, Papadopoulou C, Burns-Cunningham K, Simpson M, Maguire R. A systematic review of the supportive care needs of people living with and beyond cancer of the colon and/or rectum. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2017;29:60–70.

Harrison JD, Young JM, Price MA, Butow PN, Solomon MJ. What are the unmet supportive care needs of people with cancer? A systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17(8):1117–28.

Swash B, Hulbert-Williams N, Bramwell R. Unmet psychosocial needs in haematological cancer: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(4):1131–41.

Bootsma TI, Duijveman P, Pijpe A, Scheelings PC, Witkamp AJ, Bleiker EMA. Unmet information needs of men with breast cancer and health professionals. Psychooncology. 2020;29(5):851–60.

Brown MT, McElroy JA. Unmet support needs of sexual and gender minority breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(4):1189–96.

Barr K, Hill D, Farrelly A, Pitcher M, White V. Unmet information needs predict anxiety in early survivorship in young women with breast cancer. J Cancer Survivor : Res Pract. 2020;14(6):826–33.

Vreman RA, Heikkinen I, Schuurman A, Sapede C, Garcia JL, Hedberg N, Athanasiou D, Grueger J, Leufkens HGM, Goettsch WG. Unmet medical need: an introduction to definitions and stakeholder perceptions. Value Health. 2019;22(11):1275–82.

The Academy of Medical Sciences. Unmet need in healthcare. 2017. https://acmedsci.ac.uk/.

Moghaddam N, Coxon H, Nabarro S, Hardy B, Cox K. Unmet care needs in people living with advanced cancer: a systematic review. Support Cancer. 2016;24(8):3609–22.

Batehup L, Gage H, Williams P, Richardson A, Porter K, Simmonds P, Lowson E, Dodson L, Davies N, Wagland R, et al. Unmet supportive care needs of breast, colorectal and testicular cancer survivors in the first 8 months post primary treatment: a prospective longitudinal survey. Eur J Cancer Care. 2021;30(6): e13499.

Oh HM, Son CG. The risk of psychological stress on cancer recurrence: a systematic review. Cancers. 2021;13(22):5816.

Tola YO, Chow KM, Liang W. Effects of non-pharmacological interventions on preoperative anxiety and postoperative pain in patients undergoing breast cancer surgery: a systematic review. J Clin Nurs. 2021;30(23–24):3369–84.

Hart NH, Crawford-Williams F, Crichton M, Yee J, Smith TJ, Koczwara B, Fitch MI, Crawford GB, Mukhopadhyay S, Mahony J, et al. Unmet supportive care needs of people with advanced cancer and their caregivers: a systematic scoping review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2022;176: 103728.

Roberts C, Toohey K, Paterson C. The experiences and unmet supportive care needs of partners of men diagnosed with prostate cancer: a meta-aggregation systematic review. Cancer Nurs. 2022.

Cochrane A, Woods S, Dunne S, Gallagher P. Unmet supportive care needs associated with quality of life for people with lung cancer: a systematic review of the evidence 2007–2020. Eur J Cancer Care. 2022;31(1): e13525.

Paterson C, Jensen BT, Jensen JB, Nabi G. Unmet informational and supportive care needs of patients with muscle invasive bladder cancer: a systematic review of the evidence. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2018;35:92–101.

Shunmugasundaram C, Rutherford C, Butow PN, Sundaresan P, Dhillon HM. Content comparison of unmet needs self-report measures used in patients with head and neck cancer: a systematic review. Psychooncology. 2019;28(12):2295–306.

Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141–6.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Zeng X, Zhang Y, Kwong JS, Zhang C, Li S, Sun F, Niu Y, Du L. The methodological quality assessment tools for preclinical and clinical studies, systematic review and meta-analysis, and clinical practice guideline: a systematic review. J Evid Based Med. 2015;8(1):2–10.

Lee I, Lee J, Lee SK, Shin H-J, Jung S-Y, Lee JW, Kim Z, Lee MH, Lee J, Youn HJ. Physicians’ awareness of the breast cancer survivors’ unmet needs in Korea. J Breast Cancer. 2021;24(1):85–96.

Tsung EJF, Lian CW. Factors contributing to unmet needs among breast cancer survivors in Kuching, Sarawak: A mixed methods study. Med J Malaysia. 2017;72:25.

Cheng KKF, Cheng HL, Wong WH, Koh C. A mixed-methods study to explore the supportive care needs of breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2018;27(1):265–71.

Baker BS, Hoffman CJ, Fenlon D. What can a third sector organisation provide for people with breast cancer that public health services cannot? Developing support services in response to service evaluation. Eur J Integr Med. 2019;30:100943.

Autade Y, Chauhan G. Assess the prevalence for needs of breast cancer survivors’ in the oncology ward at a selected tertiary care hospital. J Pharmaceut Res Int. 2021;33(55A):1–12.

de Ligt KM, Heins M, Verloop J, Smorenburg CH, Korevaar JC, Siesling S. Patient-reported health problems and healthcare use after treatment for early-stage breast cancer. Breast (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2019;46:4–11.

Dugan AG, Decker RE, Namazi S, Cavallari JM, Bellizzi KM, Blank TO, Dornelas EA, Tannenbaum SH, Shaw WS, Swede H, et al. Perceptions of clinical support for employed breast cancer survivors managing work and health challenges. J Cancer Survivor : Res Pract. 2021;15(6):890–905.

McGarry S, Ward C, Garrod R, Marsden J. An exploratory study into the unmet supportive needs of breast cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Care. 2013;22(5):673–83.

Vander Meer L, Vallance JK, Ball GDC, Johnson ST. Examining lifestyle information sources, needs, and preferences among breast cancer survivors in Northern British Columbia. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2017;78(4):212–6.

McDonough AL, Lei Y, Kwak AH, Haggett DE, Jimenez RB, Johnston KT, Moy B, Spring LM, Peppercorn J. Implementation of a brief screening tool to identify needs of breast cancer survivors. Clin Breast Cancer. 2021;21(1):e88–95.

von Heymann-Horan AB, Dalton SO, Dziekanska A, Christensen J, Andersen I, Mertz BG, Olsen MH, Johansen C, Bidstrup PE. Unmet needs of women with breast cancer during and after primary treatment: a prospective study in Denmark. Acta Oncol (Stockholm, Sweden). 2013;52(2):382–90.

Palmer SC, Blauch AN, Pucci DA, Jacobs LA. Symptom burden, unmet need for assistance, and psychosocial adaptation among longer term breast cancer survivors. Cancer Res. 2017;77:51312.

Schmid-Buechi S, Halfens RJG, Mueller M, Dassen T, van den Borne B. Factors associated with supportive care needs of patients under treatment for breast cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17(1):22–9.

Schmidt ME, Wiskemann J, Steindorf K. Quality of life, problems, and needs of disease-free breast cancer survivors 5 years after diagnosis. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(8):2077–86.

Han S, Won KH, Sung YD, Ran KM. Quality of life and supportive care needs of back-to-work breast cancer survivors. Korean J Adult Nurs. 2019;31(5):552–61.

Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Hunt GE, Pendlebury S, Hobbs KM, Wain G. Breast cancer survivors’ supportive care needs 2–10 years after diagnosis. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15(5):515–23.

Gilmore KR, Damani S, King RM, Nelson B, Austin A, Scroggs S, et al. A program evaluation of best practice methods to assess integrated health needs for breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(30):111.

Tan ASL, Nagler RH, Hornik RC, DeMichele A. Evolving information needs among colon, breast, and prostate cancer survivors: results from a longitudinal mixed-effects analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2015;24(7):1071–8.

Lo-Fo-Wong DN, de Haes HC, Aaronson NK, van Abbema DL, Admiraal JM, den Boer MD, van Hezewijk M, Immink M, Kaptein AA, Menke-Pluijmers MB, et al. Health care use and remaining needs for support among women with breast cancer in the first 15 months after diagnosis: the role of the GP. Fam Pract. 2020;37(1):103–9.

Thewes B, Butow P, Girgis A, Pendlebury S. Assessment of unmet needs among survivors of breast cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2004;22(1):51–73.

Schmid-Buchi S, Halfens RJG, Dassen T, van den Borne B. Psychosocial problems and needs of posttreatment patients with breast cancer and their relatives. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15(3):260–6.

Akechi T, Okuyama T, Endo C, Sagawa R, Uchida M, Nakaguchi T, Akazawa T, Yamashita H, Toyama T, Furukawa TA. Patient’s perceived need and psychological distress and/or quality of life in ambulatory breast cancer patients in Japan. Psychooncology. 2011;20(5):497–505.

Cheng KKF, Devi RD, Wong WH, Koh C. Perceived symptoms and the supportive care needs of breast cancer survivors six months to five years post-treatment period. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2014;18(1):3–9.

Chyon MS. Yong Sik Jung MD, Jung Y, 박진희: Changes of supportive care needs and quality of life in patients with breast cancer. Asian Oncol Nurs. 2016;16(4):217–25.

Edib Z, Kumarasamy V, Abdullah NB, Rizal AM, Al-Dubai SAR. Most prevalent unmet supportive care needs and quality of life of breast cancer patients in a tertiary hospital in Malaysia. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14:26.

Fong EJ, Cheah WL. Unmet supportive care needs among breast cancer survivors of community-based support group in Kuching Sarawak. Int J Breast Cancer. 2016;2016:7297813.

Lam WWT, Au AHY, Wong JHF, Lehmann C, Koch U, Fielding R, Mehnert A. Unmet supportive care needs: a cross-cultural comparison between Hong Kong Chinese and German Caucasian women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;130(2):531–41.

Mirzaei F, Nourizadeh R, Hemmatzadeh S, Zamiri RE, Farshbaf-Khalili A. Supportive care needs in females with breast cancer under chemotherapy and radiotherapy and its predictors. Int J Womens Health Reprod Sci. 2019;7(3):366–71.

So WK, Chow KM, Chan HY, Choi KC, Wan RW, Mak SS, Chair SY, Chan CW. Quality of life and most prevalent unmet needs of Chinese breast cancer survivors at one year after cancer treatment. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2014;18(3):323–8.

Wang S, Li Y, Li C, Qiao Y, He S. Distribution and determinants of unmet need for supportive care among women with breast cancer in China. Med Sci Monit : Int Med J Exp Clin Res. 2018;24:1680–7.

Gálvez-Hernández L, Páez-Gerardo I, Ramírez-Medina R, Neri-Flores V, Bargallo-Rocha E, Villarreal-Garza C, et al. Quality of life, unmet needs and social support of patients with breast cancer during adjuvant endocrine therapy in Mexico. Cancer Res. 2019;79(4):12–15.

So WKW, Chan CWH, Choi KC, Wan RWM, Mak SSS, Chair SY. Perceived unmet needs and health-related quality of life of chinese cancer survivors at 1 year after treatment. Cancer Nurs. 2013;36(3):E23–32.

Chowdhury SH, Banu B, Akter N, Hossain SM. Unmet supportive care needs and predictor of breast cancer patients in Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2021;28(8):10781552211039114.

Fong EJ, Cheah WL, Helmy H. Determining unmet needs among breast cancer survivors - an exploratory sequential mixed methods study. Turk Onkoloji Dergisi-Turkish J Oncol. 2019;34(1):1–11.

Abdollahzadeh F, Moradi N, Pakpour V, Rahmani A, Zamanzadeh V, Mohammadpoorasl A, Howard F. Un-met supportive care needs of Iranian breast cancer patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(9):3933–8.

Choi KC, So WKW, Ho SSM, Chan CWH, Mak SSS, Wan RWM, Chair SY. Supportive care needs and quality of life among Chinese breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:S141.

Hwang SY, Park B-W. The perceived care needs of breast cancer patients in Korea. Yonsei Med J. 2006;47(4):524–33.

Park BW, Hwang SY. Unmet needs of breast cancer patients relative to survival duration. Yonsei Med J. 2012;53(1):118–25.

Park BW, Hwang SY. Unmet needs and their relationship with quality of life among women with recurrent breast cancer. J Breast Cancer. 2012;15(4):454–61.

Burris JL, Armeson K, Sterba KR. A closer look at unmet needs at the end of primary treatment for breast cancer: a longitudinal pilot study. Behav Med (Washington, DC). 2015;41(2):69–76.

Ellegaard MB, Grau C, Zachariae R, Bonde Jensen A. Fear of cancer recurrence and unmet needs among breast cancer survivors in the first five years. A cross-sectional study. Acta Oncol (Stockholm, Sweden). 2017;56(2):314–320.

Chae BJ, Lee J, Lee SK, Shin HJ, Jung SY, Lee JW, Kim Z, Lee MH, Lee J, Youn HJ. Unmet needs and related factors of Korean breast cancer survivors: a multicenter, cross-sectional study. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):839.

Vuksanovic D, Sanmugarajah J, Lunn D, Sawhney R, Eu K, Liang R. Unmet needs in breast cancer survivors are common, and multidisciplinary care is underutilised: the Survivorship Needs Assessment Project. Breast cancer (Tokyo, Japan). 2021;28(2):289–97.

Bu X, Jin C, Fan R, Cheng ASK, Ng PHF, Xia Y, Liu X. Unmet needs of 1210 Chinese breast cancer survivors and associated factors: a multicentre cross-sectional study. BMC Cancer. 2022;22(1):135.

Capelan M, Battisti NML, McLoughlin A, Maidens V, Snuggs N, Slyk P, Peckitt C, Ring A. The prevalence of unmet needs in 625 women living beyond a diagnosis of early breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2017;117(8):1113–20.

Chou YH, Chia-Rong Hsieh V, Chen X, Huang TY, Shieh SH. Unmet supportive care needs of survival patients with breast cancer in different cancer stages and treatment phases. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;59(2):231–6.

Chua GP, Ng QS, Tan HK, Ong WS. Determining the concerns of breast cancer survivors to inform practice. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2020;7(4):319–27.

Farrelly A, White V, Meiser B, Jefford M, Young M-A, Ieropoli S, Winship I, Duffy J. Unmet support needs and distress among women with a BRCA1/2 mutation. Fam Cancer. 2013;12(3):509–18.

Shih IH, Lin CY, Fang SY. Prioritizing care for women with breast cancer based on survival stage: a study examining the association between physical symptoms, psychological distress and unmet needs. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2020;48: 101816.

Napoles A, Santoyo-Olsson J, Ortiz C, Stewart A. Meeting the post-treatment self-care needs of spanish-speaking latinas after breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2016;25:122.

Sleight AG, Lyons KD, Vigen C, Macdonald H, Clark F. Supportive care priorities of low-income Latina breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(11):3851–9.

Elsous A, Radwan M, Najjar S, Masad A, Abu Rayya M. Unmet needs and health-related quality of life of breast cancer survivors: survey from Gaza Strip, Palestine. Acta Oncol (Stockholm, Sweden). 2023;62(2):194–209.

Burgmann M, Hermelink K, Farr A, Heiduschka A, Van Meegen F, Engel J, et al. Cancer-specific distress, life satisfaction and parenting concerns in young breast cancer survivors. Cancer Res. 2016;76(4):41113.

Gálvez-Hernández CL, Ortega Mondragón A, Villarreal-Garza C, Ramos Del Río B. Young women with breast cancer: Supportive care needs and resilience. Psicooncologia. 2018;15(2):287–300.

Beatty L, Oxlad M, Koczwara B, Wade TD. The psychosocial concerns and needs of women recently diagnosed with breast cancer: a qualitative study of patient, nurse and volunteer perspectives. Health Expect. 2008;11(4):331–42.

Adams N, Gisiger-Camata S, Hardy CM, Thomas TF, Jukkala A, Meneses K. Evaluating survivorship experiences and needs among rural African American breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Educ. 2017;32(2):264–71.

ArikanDonmez A, Kuru Alici N, Borman P. Lived experiences for supportive care needs of women with breast cancer-related lymphedema: a phenomenological study. Clin Nurs Res. 2021;30(6):799–808.

Beaver K, Williamson S, Briggs J. Exploring patient experiences of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2016;20:77–86.

Chen H-l, Wang X-c, Wang J-b, Zhang J-b. Wang Y: Quality of life in patients with breast cancer and their rehabilitation needs. Pakistan J Med Sci. 2014;30(1):126–30.

Cheng H, Sit JWH, Cheng KKF. Negative and positive life changes following treatment completion: Chinese breast cancer survivors’ perspectives. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(2):791–8.

Ddungu H, Kumaketch E, Namisango E. Assessment of clinical and psychological needs of patients with metastatic breast cancer: challenges and gaps in meeting their needs in Uganda. J Glob Oncol. 2018;4:11S.

Dsouza SM, Vyasa N, Narayanan P, Parsekar SS, Gore M, Sharan K. A qualitative study on experiences and needs of breast cancer survivors in Karnataka, India. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2018;6(2):69–74.

Enzler CJ, Torres S, Jabson J, Ahlum Hanson A, Bowen DJ. Comparing provider and patient views of issues for low-resourced breast cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2019;28(5):1018–24.

Haynes-Maslow L, Allicock M, Johnson L-S. Cancer support needs for African American breast cancer survivors and caregivers. J Cancer Educ. 2016;31(1):166–71.

Hubbeling HG, Rosenberg SM, Cecilia Gonzalez-Robledo M, Cohn JG, Villarreal-Garza C, Partridge AH, et al. Psychosocial needs of young breast cancer survivors in Mexico City, Mexico. PloS one 2018;13(5):e0197931.

Keesing S, Rosenwax L, McNamara B. A call to action: The need for improved service coordination during early survivorship for women with breast cancer and partners. Women Health. 2019;59(4):406–19.

Landmark BT, Bohler A, Loberg K, Wahl AK. Women with newly diagnosed breast cancer and their perceptions of needs in a health-care context - A focus group study of women attending a breast diagnostic centre in Norway. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(7B):192–200.

Oxlad M, Wade TD, Hallsworth L, Koczwara B. “I’m living with a chronic illness, not … dying with cancer”: a qualitative study of Australian women’s self-identified concerns and needs following primary treatment for breast cancer. Eur J Cancer Care. 2008;17(2):157–66.

Nápoles AM, Ortiz C, Santoyo-Olsson J, Stewart AL, Lee HE, Duron Y, Dixit N, Luce J, Flores DJ. Post-Treatment Survivorship Care Needs of Spanish-speaking Latinas with Breast Cancer. J Community Support Oncol. 2017;15(1):20–7.

Tanjasiri SP, Mata’alii S, Hanneman M, Sabado MD. Needs and experiences of Samoan breast cancer survivors in Southern California. Hawaii Med J. 2011;70(11 Suppl 2):35–9.

Pembroke M, Bradley J, Nemeth LS. Breast cancer survivors’ unmet needs after completion of radiation therapy treatment. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2020;47(4):436–45.

Ruddy KJ, Greaney ML, Sprunck-Harrild K, Meyer ME, Emmons KM, Partridge AH. Young women with breast cancer: a focus group study of unmet needs. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2013;2(4):153–60.

Ruddy KJ, Greaney ML, Sprunck-Harrild K, Meyer ME, Emmons KM, Partridge AH. A qualitative exploration of supports and unmet needs of diverse young women with breast cancer. J Community Support Oncol. 2015;13(9):323–9.

Lo-Fo-Wong DNN, de Haes H, Aaronson NK, van Abbema DL, den Boer MD, van Hezewijk M, Immink M, Kaptein AA, Menke-Pluijmers MBE, Reyners AKL, et al. Risk factors of unmet needs among women with breast cancer in the post-treatment phase. Psychooncology. 2020;29(3):539–49.

Palmer SC, DeMichele A, Schapira MM, Glanz K, Blauch A, Pucci DA, et al. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs), unmet need, and psychosocial adaptation among recent breast cancer (BC) survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(3):212.

Palmer SC, DeMichele A, Schapira MM, Glanz K, Blauch A, Pucci DA, et al. Association of anxiety and depressive symptoms with differing needs among recent breast cancer (BC) survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(3):244.

Martinez P, Andreu Y, Conchado A. Psychometric properties of the spanish version of the cancer survivors’ unmet needs (CaSUN-S) measure in breast cancer. Psicothema. 2021;33(1):155–63.

Partridge AH, Carey LA. Unmet needs in clinical research in breast cancer: where do we need to go? Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(11):2611–6.

Ahmad S, Fergus K, McCarthy M. Psychosocial issues experienced by young women with breast cancer: the minority group with the majority of need. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2015;9(3):271–8.

Benedict C, Fisher S, Kuma D, Pollom E, Schapira L, Kurian A, Berek JS, Palesh O. Examining associations among sexual health, unmet care needs related to sexuality, and distress in breast and gynecologic cancer survivors. Ann Behav Med. 2021;55:S605–S605.

Miyashita M, Kataoka A, Ohno S, Kawaguchi H, Nishimura J, Murakami S, Ozaki S, Yamaguchi M, Takahashi M. Unmet information needs and quality of life in young breast cancer survivors in Japan. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2011;38(2):E161–2.

Karis K-FC, Wong WH, Koh C. Symptom burden and unmet needs mediators of quality of life in breast cancer survivors: a structural equation modeling analysis. Psycho-oncology. 2015;24:100–101.

Black KZ, Eng E, Schaal JC, Johnson L-S, Nichols HB, Ellis KR, Rowley DL. The other side of through: young breast cancer survivors’ spectrum of sexual and reproductive health needs. Qual Health Res. 2020;30(13):2019–32.

Chen M, Li R, Chen Y, Ding G, Song J, Hu X, Jin C. Unmet supportive care needs and associated factors: Evidence from 4195 cancer survivors in Shanghai, China. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1054885.

Johnston L, Van Der Pols J, Ekberg S. Cancer survivors’ needs, preferences, and experiences accessing dietary information post-treatment: a scoping review. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2020;16(SUPPL 8):171.

Brédart A, Kop JL, Griesser AC, Zaman K, Panes-Ruedin B, Jeanneret W, Delaloye JF, Zimmers S, Jacob A, Berthet V, et al. Validation of the 34-item supportive care needs survey and 8-item breast module French versions (SCNS-SF34-Fr and SCNS-BR8-Fr) in breast cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Care. 2012;21(4):450–9.

Rammant E, Van Hecke A, Decaestecker K, Albersen M, Joniau S, Everaerts W, Jansen F, Mohamed NE, Colman R, Van Hemelrijck M, et al. Supportive care needs and utilization of bladder cancer patients undergoing radical cystectomy: a longitudinal study. Psychooncology. 2022;31(2):219–26.

Rimmer B, Crowe L, Todd A, Sharp L. Assessing unmet needs in advanced cancer patients: a systematic review of the development, content, and quality of available instruments. J Cancer Survivor : Res Pract. 2022;16(5):960–75.

Abu-Odah H, Molassiotis A. Yat Wa Liu J: Analysis of the unmet needs of Palestinian advanced cancer patients and their relationship to emotional distress: results from a cross-sectional study. BMC Palliat Care. 2022;21(1):72.

Wang T, Molassiotis A, Chung BPM, Tan JY. Unmet care needs of advanced cancer patients and their informal caregivers: a systematic review. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17(1):96.

Miroševič Š, Prins JB, Selič P, Zaletel Kragelj L, Klemenc Ketiš Z. Prevalence and factors associated with unmet needs in post-treatment cancer survivors: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer Care. 2019;28(3): e13060.

Ma X, Wan X, Chen C. The correlation between posttraumatic growth and social support in people with breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2022;13:1060150.

Zhang H, Zhao Q, Cao P, Ren G. Resilience and quality of life: exploring the mediator role of social support in patients with breast cancer. Med Sci Monit : Int Med J Exp Clin Res. 2017;23:5969–79.

Yang Y, Lin Y, Sikapokoo GO, Min SH, Caviness-Ashe N, Zhang J, Ledbetter L, Nolan TS. Social relationships and their associations with affective symptoms of women with breast cancer: a scoping review. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(8): e0272649.

Coughlin SS. Social determinants of breast cancer risk, stage, and survival. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;177(3):537–48.

Aubree Shay L, Parsons HM, Vernon SW. Survivorship care planning and unmet information and service needs among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2017;6(2):327–32.

Barroso-Sousa R, Jain E, Cohen O, Kim D, Buendia-Buendia J, Winer E, Lin N, Tolaney SM, Wagle N. Prevalence and mutational determinants of high tumor mutation burden in breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(3):387–94.

Perndorfer C, Soriano EC, Siegel SD, Spencer RMC, Otto AK, Laurenceau JP. Fear of cancer recurrence and sleep in couples coping with early-stage breast cancer. Ann Behav Med : Publ Soc Behav Med. 2022;56(11):1131–43.

Schapira L, Zheng Y, Gelber SI, Poorvu P, Ruddy KJ, Tamimi RM, Peppercorn J, Come SE, Borges VF, Partridge AH, et al. Trajectories of fear of cancer recurrence in young breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2022;128(2):335–43.

Kuswanto CN, Sharp J, Stafford L, Schofield P. Fear of cancer recurrence as a pathway from fatigue to psychological distress in mothers who are breast cancer survivors. Stress Health. 2022;39(1):197–208.

Lyu M-M. Siah RC-J, Lam ASL, Cheng KKF: The effect of psychological interventions on fear of cancer recurrence in breast cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2022;78(10):3069–82.

Yang Y, Sun H, Luo X, Li W, Yang F, Xu W, Ding K, Zhou J, Liu W, Garg S, et al. Network connectivity between fear of cancer recurrence, anxiety, and depression in breast cancer patients. J Affect Disord. 2022;309:358–67.

Singleton AC, Raeside R, Hyun KK, Partridge SR, Di Tanna GL, Hafiz N, Tu Q, Tat-Ko J, Sum SCM, Sherman KA et al. Electronic health interventions for patients with breast cancer: systematic review and meta-analyses. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(20):2257.

Lu H, Xie J, Gerido LH, Cheng Y, Chen Y, Sun L. Information needs of breast cancer patients: theory-generating meta-synthesis. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(7):e17907.

Venetis MK, Staples S, Robinson JD, Kearney T. Provider information provision and breast cancer patient well-being. Health Commun. 2019;34(9):1032–42.

Runowicz CD, Leach CR, Henry NL, Henry KS, Mackey HT, Cowens-Alvarado RL, Cannady RS, Pratt-Chapman ML, Edge SB, Jacobs LA et al. American Cancer Society/American Society of Clinical Oncology Breast Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline. CA: Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(1):43–73.

Im EO, Kim S, Lee C, Chee E, Mao JJ, Chee W. Decreasing menopausal symptoms of Asian American breast cancer survivors through a technology-based information and coaching/support program. Menopause (New York, NY). 2019;26(4):373–82.

Tucholka JL, Yang DY, Bruce JG, Steffens NM, Schumacher JR, Greenberg CC, Wilke LG, Steiman J, Neuman HB. A randomized controlled trial evaluating the impact of web-based information on breast cancer patients’ knowledge of surgical treatment options. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226(2):126–33.

Alinejad Mofrad S, Fernandez R, Lord H, Alananzeh I. The impact of mastectomy on Iranian women sexuality and body image: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(10):5571–80.

Alananzeh I, Green H, Meedya S, Chan A, Chang HC, Yan Z, et al. Sexual activity and cancer: a systematic review of prevalence, predictors and information needs among female Arab cancer survivors. Eur J Cancer Care. 2022;31(6):e13644.

Luo F, Link M, Grabenhorst C, Lynn B. Low sexual desire in breast cancer survivors and patients: a review. Sex Med Rev. 2022;10(3):367–75.

Ratner ES, Foran KA, Schwartz PE, Minkin MJ. Sexuality and intimacy after gynecological cancer. Maturitas. 2010;66(1):23–6.

Tsatsou I, Parpa E, Tsilika E, Katsaragakis S, Batistaki C, Dimitriadou E, Mystakidou K. A systematic review of sexuality and depression of cervical cancer patients. J Sex Marital Ther. 2019;45(8):739–54.

Abbott-Anderson K, Kwekkeboom KL. A systematic review of sexual concerns reported by gynecological cancer survivors. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;124(3):477–89.

Nimbi FM, Magno S, Agostini L, Di Micco A, Maggiore C, De Cesaris BM, Rossi R, Galizia R, Simonelli C, Tambelli R. Sexuality in breast cancer survivors: sexual experiences, emotions, and cognitions in a group of women under hormonal therapy. Breast Cancer (Tokyo, Japan). 2022;29(3):419–28.

Hastert TA, Ruterbusch JJ, McDougall JA, Robinson JRM, Strayhorn SM, Abdallah A, et al. Diagnosis in young adulthood as a risk factor for unmet social needs among African American cancer survivors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2022;31(1 SUPPL):87.

Lou Y, Yates P, Chan RJ, Ni X, Hu W, Zhuo S, Xu H. Unmet supportive care needs and associated factors: a cross-sectional survey of Chinese cancer survivors. J Cancer Educ. 2021;36(6):1219–29.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the participating patients and to all other co-investigators who contributed to this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the Sichuan Science and Technology Department (2023YFS0237, 2019YFS0383).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors had contributed to this study. Rongrong Fan conceived and designed the original study protocol. Rongrong Fan and Xiaofan Bu performed literature search and screening. Lili Wang and Wenxiu Wang takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the data analysis. Jing Zhu interpreted the results. Rongrong Fan, Wenxiu Wang, and Lili Wang assessed the risk of bias of the studies. Rongrong Fan was responsible for writing the first draft of the paper and revision of the manuscript. Xiaofan Bu was responsible for the overall content as guarantor. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This is a systematic scoping review. The Ethical institution has confirmed that no ethical approval and informed consent were required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests..

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Fan, R., Wang, L., Bu, X. et al. Unmet supportive care needs of breast cancer survivors: a systematic scoping review. BMC Cancer 23, 587 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-023-11087-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-023-11087-8