Abstract

Background

Inflammatory blood markers have been associated with oncological outcomes in several cancers, but evidence for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is scanty. Therefore, this study aims at investigating the association between five different inflammatory blood markers and several oncological outcomes.

Methods

This multi-centre retrospective analysis included 925 consecutive patients with primary HPV-negative HNSCC (median age: 68 years) diagnosed between April 2004 and June 2018, whose pre-treatment blood parameters were available. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR), lymphocyte to monocyte ratio (LMR), systemic inflammatory marker (SIM), and systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) were calculated; their associations with local, regional, and distant failure, disease-free survival (DFS), and overall survival (OS) was calculated.

Results

The median follow-up was 53 months. All five indexes were significantly associated with OS; the highest accuracy in predicting patients’ survival was found for SIM (10-year OS = 53.2% for SIM < 1.40 and 40.9% for SIM ≥ 2.46; c-index = 0.569) and LMR (10-year OS = 60.4% for LMR ≥ 3.76 and 40.5% for LMR < 2.92; c-index = 0.568). While LMR showed the strongest association with local failure (HR = 2.16; 95% CI:1.22–3.84), PLR showed the strongest association with regional (HR = 1.98; 95% CI:1.24–3.15) and distant failure (HR = 1.67; 95% CI:1.08–2.58).

Conclusion

Different inflammatory blood markers may be useful to identify patients at risk of local, regional, or distant recurrences who may benefit from treatment intensification or intensive surveillance programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Despite the strong evidence that host-related factors can significantly influence outcomes, the estimation of prognosis in cancer patients is still essentially based only on tumour parameters incorporated in the TNM staging system, evaluated by means of clinical and histopathological assessment and on performance status, judged on patient’s functionality [1]. Therefore, in current clinical practice there is still little consideration and appreciation of the prognostic potential of host-related factors.

In recent years, among the host-related factors that have aroused considerable interest, those based on the evaluation of blood parameters, in particular pre-treatment peripheral blood leukocytes, showed promising prognostic correlations [2, 3]. These indices aim to characterise the inflammatory status of the patient and embrace the concept of cancer as a systemic inflammatory disease. There is indeed increasing evidence that tumour-associated inflammation plays an important role in the development, progression and metastasis of cancer and might be related to systemic inflammation [4].

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is the sixth commonest cancer worldwide, with 890,000 new cases documented every year, and it is the seventh commonest cause of cancer-related death, with a 40–50% mortality [5]. Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a validated and robust biomarker, but its utility is however limited to oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma [6]. Therefore, other valuable prognostic biomarkers are needed for HPV–negative HNSCC.

HNSCC promotes local and systemic inflammation [6]. Thus, host factors indicating inflammatory status have also been investigated in these malignancies. Several indices have been proposed, the most of them combining routinary blood parameters such as neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, and platelets count [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. The aim of this study was to evaluate and compare the five inflammatory blood markers (IMBs) with respect to different clinical endpoints using pre-treatment blood tests in a large series of patients receiving upfront surgery for HNSCCs.

Methods

Inclusion criteria

This multi-centre retrospective study was performed in a cohort of consecutive patients diagnosed with primary HNSCC from April 1, 2004 to June 30, 2018, who underwent upfront surgery with/without adjuvant (chemo)radiotherapy. The study network included General and University Hospitals in North Italy, located in Brescia, Ferrara, Padova, Pavia, Pordenone, Treviso, Trieste, and Verona. Inclusion criteria were: (a) HNSCC arising from the oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx, or larynx; (b) curative upfront surgery as primary treatment modality; and (c) availability of pre-operative neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, and platelets count, i.e., the blood parameters necessary for the calculation of the inflammatory blood markers under investigation. Patients were specifically excluded if: (a) they were diagnosed with nasopharyngeal carcinoma or T1 glottic squamous cell carcinoma; (b) they had any coexisting conditions or haematological conditions that could alter inflammatory parameters; (c) they had previous malignancy or additional synchronous primary tumours; (d) their pre-treatment blood test results were not available; (e) they had metastatic disease; and (f) they had HPV-positive disease.

Participants and data

Medical records were reviewed to collect socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of enrolled patients. Baseline characteristics, including gender, age, smoking habits, drinking habits, cancer site, clinical and pathological TNM staging (7th edition), grading, surgical margins and extranodal extension were retrieved. For oropharyngeal carcinomas, HPV status was assessed by p16 immunostaining and/or HPV-PCR. Blood parameters collected at baseline were platelet (103/μL), haemoglobin (Hb, g/L), neutrophils (103/μL), lymphocytes (103/μL), monocytes (103/μL). Patients were routinely followed-up according to consensus guidelines [17] with endoscopic examination of the upper aero-digestive tract every one-to-three months for the first year, three-to-four months during the second year, four-to-six months during the third year, and every six months thereafter. A chest computed tomography scan was annually performed in patients with history of smoking ≥ 20 pack/year. Additional dedicated head and neck imaging was acquired based on clinical features and local protocol. No patient was lost to follow-up.

Inflammatory blood markers

Using pre-treatment blood parameters, we investigated five pre-treatment indexes: 1) neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) [7,8,9,10], calculated as NLR = neutrophils / lymphocytes; 2) platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR) [11,12,13], calculated as PLR = platelets / lymphocytes; 3) lymphocyte to monocyte ratio (LMR) [14], calculated as LMR = lymphocytes / monocytes; 4) systemic inflammatory marker (SIM) [15], calculated as SIM = [neutrophils X monocytes] / lymphocytes; 5) systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) [16], calculated as SII = [neutrophils X platelets] / lymphocytes.

Statistics

For each patient, the time at risk was computed from the date of surgery to the event date or last follow-up, whichever occurred first according to the outcome of interest. The event of interest was defined as: death from any cause for overall survival (OS); disease recurrence or death from any cause for disease-free survival (DFS); local recurrence for local failure; regional recurrence for regional failure; distant metastasis for distant failure. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to generate crude survival probabilities and the log-rank test was used to assess the heterogeneity in time to event according to strata of selected covariates [18]. To account for competing risks, local, regional, and distant failures were evaluated through cumulative incidence [19], and differences according to blood parameters were tested through Gray's test [20]. Hazard ratios (HR) and the corresponding 95% CI were calculated using Cox proportional hazards models [18], adjusting for study centre, gender, and age, plus clinically relevant covariates (i.e., pT, pN, surgical margins, extranodal extension, adjuvant [chemo]radiotherapy). For local regional, and distant recurrence, risk estimates were adjusted for competing risk according to the Fine-Gray model [19]. Blood parameters and inflammatory indexes were categorized in three levels; the optimal cut-offs were determined according to a recursive algorithm that maximizes the model predictability in OS, measured through Harrell’s C-index [21]. Haemoglobin level was categorized as low, normal or high according to gender-specific clinical cut-offs (i.e., < 12 g/L, 12–16 g/dL, and > 16 g/dL in women; < 14 g/dL, 14–18 g/dL, and > 18 g/dL in men).

Results

Population

Out of 1001 eligible patients, 925 patients were included the present analysis (median age: 68 years; interquartile range: 61–76 years). The majority of patients (n = 679, 73.4%) were male, with stage III–IV cancer (n = 642, 69.4%) and with moderately differentiated SSC (n = 469, 50.7%; Table 1). Negative surgical margins were achieved in 610 patients (65.9%) and extranodal extension was absent in 765 patients (82.7%). Adjuvant (chemo)radiotherapy was administered to 463 patients (50.1%). During a median follow-up of 53 months (interquartile range: 31–82 months), 385 patients died; cancer was the cause of death in 215 (55.8%) of them. One hundred forty-one patients experienced local recurrence, while 127 patients had regional recurrence and 111 distant metastases. A second primary head and neck or lung tumour was diagnosed during follow-up in 72 patients. Lower OS was associated with increased age (HR = 2.28; 95% CI: 1.64–3.18 for age 70–79 years and HR = 3.82; 95% CI: 2.64–5.54 for age > 80 years), more advanced pT stage (HR = 1.90; 95% CI: 1.18–3.08 for pT3 and HR = 2.52; 95% CI: 1.58–4.02 for pT4), more advanced pN stage (HR = 1.72; 95% CI: 1.23–2.40 for pN1 and HR = 2.12; 95% CI: 1.51–2.97 for pN2-pN3), close/positive surgical margins (HR = 1.27; 95% CI: 1.00–1.62), and extranodal extension (HR = 1.41; 95% CI: 1.04–1.92). Similar patterns were found for DFS (Table 1).

Blood samples were obtained at a median of 19 days days before surgery (interquartile range: 10–31 days). Supplementary Table 1 shows the association between blood parameters and patient outcomes. Low haemoglobin levels were significantly associated with lower DFS (HR = 1.35, 95% CI: 1.10–1.68) and OS (HR = 1.56, 95% CI 1.24–1.95). Moreover, lymphocyte count < 1.97 103/μL was associated with a reduction of DFS and OS.

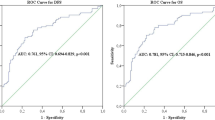

Inflammatory blood markers

Figure 1 shows Kaplan–Meier estimates of OS. Although all five indexes were significantly associated with outcome, the highest accuracy in predicting patients’ OS was found for SIM (10-year OS = 53.2% for SIM < 1.40 and 40.9% for SIM ≥ 2.46; c-index = 0.569) and LMR (10-year OS = 60.4% for LMR ≥ 3.76 and 40.5% for LMR < 2.92; c-index = 0.568). Similarly, LMR (10-year DFS = 55.2% for LMR ≥ 3.76 and 33.6% for LMR < 2.92; c-index = 0.567) and SIM (10-year DFS = 48.8% for SIM < 1.40 and 29.8% for SIM ≥ 2.46; c-index = 0.563) were the best predictors of DFS (Fig. 2). Table 2 shows the correlations between inflammatory indexes and patient’s outcomes. All five IBMs were significant predictors of DFS, with worse DFS for NLR ≥ 3.76 (HR = 1.47, 95% CI: 1.12–1.92), PLR ≥ 162.8 (HR = 1.35, 95% CI: 1.07–1.71), LRM < 2.92 (HR = 1.58, 95% CI: 1.18–2.12), SIM ≥ 2.46 (HR = 1.48, 95% CI: 1.15–1.91) and SII ≥ 754 (HR = 1.37, 95% CI: 1.11–1.70). Associations with OS were slightly weaker.

A LMR of 2.92 or less showed the strongest association with local failure (HR = 2.16; 95% CI: 1.22–3.84), while a PLR of 162.8 or higher showed the strongest association with regional (HR = 1.98; 95% CI: 1.24–3.15) and distant failure (HR = 1.67; 95% CI: 1.08–2.58) (Table 2). Compared to patients with PLR < 127.7, those with PLR ≥ 162.8 suffered a higher 5-year cumulative incidence of local failure (20.9% versus 12.7%; p = 0.0255 – Fig. 3) and regional failure (19.1% versus 10.6%; p = 0.0058). Similar trends were found for LMR < 2.92 versus LMR ≥ 3.76 for both local failure (5-year cumulative incidence: 18.5% versus 9.4%; p = 0.0164) and regional failure (17.0% versus 9.0%; p = 0.0308).

Discussion

The present study supports the use of five IBMs, which can be easily calculated in routine clinical practice using standard blood tests, as prognostic markers, offering evidence of a strong correlation with prognosis. All five IBMs analysed in the present study were good predictors of OS or DFS. However, LMR and SIM emerged as the two best performing indices in identifying patients at greatest risk of death. Of interest, it was also observed that different IBMs might predict specific patterns of failure. In particular, a low LMR showed the strongest association with local failure, while a high PLR showed the strongest association with regional and distant failure.

Chronic inflammation is a well-recognized tumour-enabling capability, which can promote cancer development and progression [22]. Inflammatory cells and their mediators are in fact an essential component of the tumour microenvironment (TME) with cancer cells being able to induce inflammatory reactions through various mechanisms [23]. In addition, there is significant dialogue between the mediators and cytokines in the local TME and the peripheral circulating compartment [24]. The tumour-derived secretome can indeed influence bone marrow to increase myelopoiesis resulting in a change in the proportions of neutrophils, monocytes, platelets, and lymphocytes [25]. Thus, IBMs based on peripheral blood-based parameters have been studied as surrogate biomarkers that may capture the inflammatory cross-talk between cancer and immune cells in the local TME [26].

Although we cannot provide a mechanistic explanation for our observations, these results are consistent with the recent evidence emerging about the role played by different inflammatory cells of the TME. While lymphocyte activation can be counterbalanced by a broad spectrum of immunosuppressive mechanisms that are present in the TME, including programmed cell death protein‐1 (PD‐1) and Forkhead box P3 (FOXP3) CD4 + regulatory T-cells [27], the presence of tumour infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in the TME is a positive prognostic marker in multiple solid tumours [28]. In particular, CD4 + T-helper 1 (Th1) cells facilitate antigen presentation through cytokine secretion and activation of antigen presenting cells, while CD8 + cytotoxic T-cells (CTL) are essential for tumour destruction [29]. On the other hand, tumour-infiltrating B-lymphocytes suppress tumour progression by secreting immunoglobulins, promoting T-cell response, and killing cancer cells directly. Finally, NK cells are part of the innate immune system able to kill tumour cells and prevent metastasis [30]. An immunohistochemical investigation showed that patients with pharyngeal and laryngeal cancer, whose tumours were densely infiltrated by T cells, cytotoxic T cells, NK cells, and stromal dendritic cells, had an improved outcome compared to patients whose cancers were poorly infiltrated [31]. Consistently, the results from a recent meta-analysis demonstrated the positive prognostic significance of CD8 + and CD4 + TILs in HNSCC [32].

Moreover, several studies have observed an inverse correlation between the NLR and the number of TILs in the TME, with a low NLR correlating with high levels of tumour-infiltrating CD8 + T cells [33, 34], thus supporting the concept that the peripheral blood compartment may predict the immune milieu in the TME.

As commonly available and measurable an index, LNR has been widely investigated as a potential prognostic biomarker in oncology. In a recent and very large retrospective series, it was observed that HNSCC patients with high NLR had both an increased hazard of all-cause mortality and of cancer-specific mortality [35]. Interestingly, baseline NLR > 5 was associated with poor outcome in patients with recurrent or metastatic HNSCC treated with nivolumab [36]. Moreover, a high NLR was significantly associated with cancer cachexia development [37] and was shown to be an independent predictor of mortality in HNSCC patients treated with primary or adjuvant chemoradiation [38]. Consistently with the above observation, NLR was found to be an independent predictor of both DFS and OS also in the present surgical series.

Macrophages are the most abundant leukocytes in the TME. Tumour-associated macrophages (TAMs) are drivers of tumour progression in established tumours, promoting cancer cell proliferation and survival, angiogenesis and lympho-angiogenesis, reducing effective T-cell responses [39]. Circulating monocytes give rise to macrophages that reside in tissues. Importantly, macrophage differentiation from monocytes occurs in the peripheral tissue in association with the gaining of a functional phenotype that depends on microenvironmental signals. Particularly, tumour and stromal cells release chemotactic factors, i.e. chemokines ligand-2 and -5, that recruit macrophages and contribute to macrophage polarization toward specific phenotypes, with interleukin (IL)-4, IL-13, IL-23, immunocomplexes, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, or macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) diverting macrophage polarization through an M2/M2-like phenotype, which sustains many aspects of tumour growth and progression [40]. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), a heterogeneous population of cells, which can suppress T-cell responses and expand during inflammation and cancer, are also derived from monocytes. Interestingly and consistently with our observation that a low LMR showed the strongest association with local failure, tumour associated macrophages (TAMs) and MDSCs may promote field cancerization by generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) that create an immunosuppressive environment allowing adjacent precancerous cells to grow, expand, and acquire a fully malignant phenotype [41]. However, no studies conducted in patients with HNSCC have investigated the predictive value of LMR specifically for local recurrence. Several studies conducted in patients with cancers other than HNSCC have reported a significant association between a low LMR and the risk of recurrence without specifying the type of tumour relapse [42,43,44]. Furthermore, TAMs have also been implicated in tumour invasion and metastasis through production of proteases, which digest the components of the extracellular matrix, by promoting the angiogenic switch and sustaining lymph angiogenesis. This may explain the weaker but still significant association between a low LMR and the risk of developing lymph node metastases observed in this series of patients.

Platelets contribute significantly to the metastatic process [45, 46]. Platelets form a shield around metastatic cells protecting them from immune surveillance, and also induce matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 expression and activation leading to increased remodelling of the extracellular matrix, release of growth factors from the extracellular matrix, and relief of intercellular contacts, thus facilitating cancer cell dissemination and metastasis [45]. Finally, platelets can also increase microvascular permeability, leading to intravasation of cancer cells into the circulation [46].

These properties may explain the association we observed in our series between a high PLR and a significantly higher risk of regional and distant failure. In previous work on HNSCC, PLR has mainly been investigated for its ability to predict OS and DFS but not more specific endpoints [47,48,49]. However, preoperative PLR has been observed to be superior to NLR as a predictive marker for lymph node metastasis in oral squamous cell carcinoma [50]. Similarly, a recent meta-analysis showed that a high PLR was significantly associated with a higher risk of lymph node metastasis in patients with gastric cancer [51]. Moreover, in breast cancer, a persistently high PLR was observed to be associated with worse metastatic-free survival [52]. These findings support the hypothesis that PLR may be a surrogate marker for the propensity of cancer cells to metastasize. Of interest, PLR was also found to be a predictor of good response to induction chemotherapy in patients with HNSCC [53].

IBMs have been investigated in HNSCC mainly in single-centre retrospective studies. The present multicentre study provides a large cohort of highly selected patients with strict inclusion criteria, and follow-up with regular clinical examination as recommended by the American Cancer Society. However, this study has some limitations. Firstly, the retrospective design may have biased the results. Secondly, blood parameters were collected pre-operatively in order to avoid the influence of surgery itself on the baseline values. However, it was not always possible to exclude the effect of any other systemic condition, as the investigated IBMs are not tumour-specific markers. Furthermore, specific treatment protocols (including the type of surgery) were not assessed, therefore, the estimated risk did not account for them. However, multivariable model included the study centre as a covariate, which may have partially captured the heterogeneity of treatment approaches across centres. Lastly, given the period of time during which selected patients were diagnosed and treated, HNSCC were staged according to the 7th edition of the American Joint Commission on Cancer TNM. However, considering that we excluded patients with HPV-driven cancers, the divergence between the 7th and the 8th editions of TNM in our series is limited.

Conclusions

In this retrospective observational study of patients undergoing surgical treatment for HPV-negative HNSCC, different IBMs were observed to be predictive of different patterns of failure. Thus, different IBMs may be useful not only to stratify prognosis but also to identify patients at risk of local, regional, and distant recurrences thus guiding surveillance follow-up strategies and (neo)adjuvant treatment. In this regard, the integration of immunotherapy as therapeutic weapon in the comprehensive approach to HNSCC may be better tailored according to the above-described parameters. Further research is required to confirm and validate these findings, to investigate their use in non-surgically managed HNSCC, and to support the use of different IBMs to predict different clinical endpoints.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DFS:

-

Disease-free survival

- HNSCC:

-

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- IBM:

-

Inflammatory blood markers

- LMR:

-

Lymphocyte to monocyte ratio

- MDSC:

-

Myeloid-derived suppressor cell

- NLR:

-

Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PLR:

-

Platelet to lymphocyte ratio

- SII:

-

Systemic immune-inflammation index

- SIM:

-

Systemic inflammatory marker

- TAM:

-

Tumour-associated macrophage

- TIL:

-

Tumour infiltrating lymphocytes

- TME:

-

Tumour microenvironment

References

Valero C, Zanoni DK, Pillai A, Ganly I, Morris LGT, Shah JP, et al. Host Factors Independently Associated With Prognosis in Patients With Oral Cavity Cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;146:699–707.

Tham T, Bardash Y, Herman SW, Costantino PD. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic indicator in head and neck cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck. 2018;40:2546–57.

Starzer AM, Steindl A, Mair MJ, Deischinger C, Simonovska A, Widhalm G, et al. Systemic inflammation scores correlate with survival prognosis in patients with newly diagnosed brain metastases. Br J Cancer Nature Publishing Group. 2021;124:1294–300.

Galdiero MR, Bonavita E, Barajon I, Garlanda C, Mantovani A, Jaillon S. Tumor associated macrophages and neutrophils in cancer. Immunobiology. 2013;218:1402–10.

Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, Weber R, Rosenthal DI, Nguyen-Tân PF, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:24–35.

Johnson DE, Burtness B, Leemans CR, Lui VWY, Bauman JE, Grandis JR. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 2020;6:92.

Li M-X, Liu X-M, Zhang X-F, Zhang J-F, Wang W-L, Zhu Y, et al. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:2403–13.

Wei Y, Jiang YZ, Qian WH. Prognostic Role of NLR in Urinary Cancers: A Meta-Analysis. PLOS ONE. 2014;9:e92079.

Zhang X, Zhang W, Feng L. Prognostic Significance of Neutrophil Lymphocyte Ratio in Patients with Gastric Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. PLOS ONE. 2014;9:e111906.

Yang J-J, Hu Z-G, Shi W-X, Deng T, He S-Q, Yuan S-G. Prognostic significance of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in pancreatic cancer: A meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:2807–15.

Yodying H, Matsuda A, Miyashita M, Matsumoto S, Sakurazawa N, Yamada M, et al. Prognostic Significance of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Oncologic Outcomes of Esophageal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:646–54.

Baranyai Z, Jósa V, Tóth A, Szilasi Z, Tihanyi B, Zaránd A, et al. Paraneoplastic thrombocytosis in gastrointestinal cancer. Platelets. 2016;27:269–75.

Li B, Zhou P, Liu Y, Wei H, Yang X, Chen T, et al. Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in advanced Cancer: Review and meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta Int J Clin Chem. 2018;483:48–56.

Pan YC, Jia ZF, Cao DH, Wu YH, Jiang J, Wen SM, et al. Preoperative lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR) could independently predict overall survival of resectable gastric cancer patients. Medicine. 2018;97:e13896.

Zhou S, Yuan H, Wang J, Hu X, Liu F, Zhang Y, et al. Prognostic value of systemic inflammatory marker in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma undergoing surgical resection. Future Oncol Lond Engl. 2020;16:559–71.

Shi H, Jiang Y, Cao H, Zhu H, Chen B, Weiwei Ji. Nomogram Based on Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index to Predict Overall Survival in Gastric Cancer Patients. Dis Markers. 2018; 1787424.

Simo R, Homer J, Clarke P, Mackenzie K, Paleri V, Pracy P, et al. Follow-up after treatment for head and neck cancer: United Kingdom National Multidisciplinary Guidelines. J Laryngol Otol. 2016;130:S208–11.

Kalbfleisch JD, Prentice RL. The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2002.

Fine JP, Gray RJ. A Proportional Hazards Model for the Subdistribution of a Competing Risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496–509.

Gray RJ. A Class of K-Sample Tests for Comparing the Cumulative Incidence of a Competing Risk. Ann Stat. 1988;16:1141–54.

Harrell FE, Califf RM, Pryor DB, Lee KL, Rosati RA. Evaluating the yield of medical tests. JAMA. 1982;247:2543–6.

Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–74.

Granja S, Tavares-Valente D, Queirós O, Baltazar F. Value of pH regulators in the diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2017;43:17–34.

Diakos CI, Charles KA, McMillan DC, Clarke SJ. Cancer-related inflammation and treatment effectiveness. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e493-503.

Gabrilovich DI, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Bronte V. Coordinated regulation of myeloid cells by tumours. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:253–68.

Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860–7.

Shimasaki N, Jain A, Campana D. NK cells for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19:200–18.

Fridman WH, Pagès F, Sautès-Fridman C, Galon J. The immune contexture in human tumours: impact on clinical outcome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:298–306.

van der Leun AM, Thommen DS, Schumacher TN. CD8+ T cell states in human cancer: insights from single-cell analysis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020;20:218–32.

Guillerey C, Huntington ND, Smyth MJ. Targeting natural killer cells in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:1025–36.

Karpathiou G, Casteillo F, Giroult JB, Forest F, Fournel P, Monaya A, et al. Prognostic impact of immune microenvironment in laryngeal and pharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: Immune cell subtypes, immuno-suppressive pathways and clinicopathologic characteristics. Oncotarget. 2017;8:19310–22.

Borsetto D, Tomasoni M, Payne K, Polesel J, Deganello A, Bossi P, et al. Prognostic Significance of CD4+ and CD8+ Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Meta-Analysis. Cancers. 2021;13:781.

Tanaka R, Kimura K, Eguchi S, Tauchi J, Shibutani M, Shinkawa H, et al. Preoperative Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte Ratio Predicts Tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T Cells in Biliary Tract Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2020;40:2881–7.

Franz L, Alessandrini L, Fasanaro E, Gaudioso P, Carli A, Nicolai P, et al. Prognostic impact of neutrophils-to-lymphocytes ratio (NLR), PD-L1 expression and tumor immune microenvironment in laryngeal cancer. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2021;50:151657.

Ferrandino RM, Roof S, Garneau J, Haidar Y, Bates SE, Park YHA, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic indicator for overall and cancer-specific survival in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 2020;42:2830–40.

Ueda T, Chikuie N, Takumida M, Furuie H, Kono T, Taruya T, et al. Baseline neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is associated with clinical outcome in recurrent or metastatic head and neck cancer patients treated with nivolumab. Acta Otolaryngol. 2020;140:181–7.

Xu C, Yuan J, Du W, Wu J, Fang Q, Zhang X, Li H. Significance of the Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in p16-Negative Squamous Cell Carcinoma of Unknown Primary in Head and Neck. Front Oncol. 2020;10:39.

Bojaxhiu B, Templeton AJ, Elicin O, Shelan M, Zaugg K, Walser M, et al. Relation of baseline neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio to survival and toxicity in head and neck cancer patients treated with (chemo-) radiation. Radiat Oncol. 2018;13:216.

Noy R, Pollard JW. Tumor-Associated Macrophages: From Mechanisms to Therapy. Immunity. 2014;41:49–61.

Kitamura T, Qian B-Z, Soong D, Cassetta L, Noy R, Sugano G, et al. CCL2-induced chemokine cascade promotes breast cancer metastasis by enhancing retention of metastasis-associated macrophages. J Exp Med. 2015;212:1043–59.

Liao Z, Chua D, Tan NS. Reactive oxygen species: a volatile driver of field cancerization and metastasis. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:65.

Ma J-Y, Hu G, Liu Q. Prognostic Significance of the Lymphocyte-to-Monocyte Ratio in Bladder Cancer Undergoing Radical Cystectomy: A Meta-Analysis of 5638 Individuals. Dis Markers. 2019;2019:7593560.

Yokota M, Katoh H, Nishimiya H, Kikuchi M, Kosaka Y, Sengoku N, et al. Lymphocyte-Monocyte Ratio Significantly Predicts Recurrence in Papillary Thyroid Cancer. J Surg Res. 2020;246:535–43.

Cananzi FCM, Minerva EM, Samà L, Ruspi L, Sicoli F, Conti L, et al. Preoperative monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts recurrence in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Surg Oncol. 2019;119:12–20.

Janowska-Wieczorek A, Wysoczynski M, Kijowski J, Marquez-Curtis L, Machalinski B, Ratajczak J, et al. Microvesicles derived from activated platelets induce metastasis and angiogenesis in lung cancer. Int J Cancer. 2005;113:752–60.

Palacios-Acedo AL, Mège D, Crescence L, Dignat-George F, Dubois C, Panicot-Dubois L. Platelets, Thrombo-Inflammation, and Cancer: Collaborating With the Enemy. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1805.

Abelardo E, Davies G, Kamhieh Y, Prabhu V. Are Inflammatory Markers Significant Prognostic Factors for Head and Neck Cancer Patients? ORL J Oto-Rhino-Laryngol Its Relat Spec. 2020;82:235–44.

Rassouli A, Saliba J, Castano R, Hier M, Zeitouni AG. Systemic inflammatory markers as independent prognosticators of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2015;37:103–10.

Wang X, Cao K, Guo E, Mao X, An C, Guo L, et al. Assessment of immune status of laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma can predict prognosis and guide treatment. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00262-021-03071-7.

Acharya S, Rai P, Hallikeri K, Anehosur V, Kale J. Preoperative platelet lymphocyte ratio is superior to neutrophil lymphocyte ratio to be used as predictive marker for lymph node metastasis in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Investig Clin Dent. 2017;8:e12219.

Zhang X, Zhao W, Yu Y, Qi X, Song L, Zhang C, et al. Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of platelet-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) in gastric cancer: an updated meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2020;18:191.

Kim J-Y, Jung EJ, Kim J-M, Lee HS, Kwag S-J, Park J-H, et al. Dynamic changes of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts breast cancer prognosis. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:1206.

Karpathiou G, Giroult JB, Forest F, Fournel P, Monaya A, Froudarakis M, et al. Clinical and Histologic Predictive Factors of Response to Induction Chemotherapy in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2016;146:546–53.

Acknowledgements

The Authors thank Mrs Luigina Mei (Unit of Cancer Epidemiology, Centro di Riferimento Oncologico di Aviano – CRO – IRCCS) for editorial assistance.

Funding

The work of Dr. Polesel was partially supported by Ministero della Salute – Ricerca Corrente [No grant number available]. The funding body played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Paolo Boscolo-Rizzo, Daniele Borsetto, Giancarlo Tirelli; methodology: Paolo-Boscolo Rizzo, Daniele Borsetto, and Jerry Polesel; data collection and quality control: Margherita Tofanelli, Alberto Deganello, Michele Tomasoni, Piero Nicolai, Paolo Bossi, Giacomo Spinato, Anna Menegaldo, Andrea Ciorba, Stefano Pelucchi, Chiara Bianchini, Diego Cazzador, Giulia Ramaciotti, Valentina Lupato, Vittorio Giacomarra, Gabriele Molteni, Daniele Marchioni, Cristoforo Fabbris, Antonio Occhini, Giulia Bertino; formal analysis and investigation: Jerry Polesel; writing-original draft preparation: Paolo Boscolo-Rizzo, Jerry Polesel, and Andrea D’Alessandro; supervision: Jonathan Fussey; critical revision of the manuscript: all the authors. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted with the approval of the Board of Ethics of Treviso/Belluno provinces (Date March 23rd, 2020/No. 773/CE Marca). Written consent to participate was obtained from patients in accordance to Italian rules and regulations, in agreement to requirement of the Board of Ethics that approved the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Risk of recurrence and death according to blood parameters

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Boscolo-Rizzo, P., D’Alessandro, A., Polesel, J. et al. Different inflammatory blood markers correlate with specific outcomes in incident HPV-negative head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Cancer 22, 243 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-022-09327-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-022-09327-4