Abstract

Background

Targeting Protein for Xenopus Kinesin Like Protein 2 (TPX2) is a microtubule associated protein that functions in mitotic spindle assembly. TPX2 also localizes to the nucleus where it functions in DNA damage repair during S-phase. We and others have previously shown that TPX2 RNA levels are strongly associated with chromosomal instability (CIN) in breast and other cancers, and TPX2 RNA levels have been demonstrated to correlate with aggressive behavior and poor clinical outcome across a range of solid malignancies, including breast cancer.

Methods

We perform TPX2 IHC on a cohort of 253 primary breast cancers and adopt a clinically amenable scoring system to separate tumors into low, intermediate, or high TPX2 expression. We then correlate TPX2 expression against diverse pathologic parameters and important measures of clinical outcome, including disease-specific and overall survival. We link TPX2 expression to TP53 mutation and evaluate whether TPX2 is an independent predictor of chromosomal instability (CIN).

Results

We find that TPX2 nuclear expression strongly correlates with high grade morphology, elevated clinical stage, negative ER and PR status, and both disease-specific and overall survival. We also show that increased TPX2 nuclear expression correlates with elevated ploidy, supernumerary centrosomes, and TP53 mutation. TPX2 nuclear expression correlates with CIN via univariate analyses but is not independently predictive when compared to ploidy, Ki67, TP53 mutational status, centrosome number, and patient age.

Conclusions

Our findings demonstrate a strong correlation between TPX2 nuclear expression and aggressive tumor behavior, and show that TPX2 overexpression frequently occurs in the setting of TP53 mutation and elevated ploidy. However, TPX2 expression is not an independent predictor of CIN where it fails to outperform existing clinical and pathologic metrics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Targeting Protein for Xenopus Kinesin Like Protein 2 (TPX2) is a microtubule associated protein which critically regulates the formation of the mitotic spindle during mitosis, primarily by localizing and activating Aurora A kinase [1]. TPX2 also enhances microtubule nucleation independent of Aurora A, assists in the targeting of mitotic kinesins to microtubule minus ends, and works in concert with Augmin to form microtubule branch points [2]. Together, these activities maintain genomic stability by ensuring the proper segregation of chromosomes during mitosis. During interphase, TPX2 localizes to the nucleus where it plays a role in the DNA damage response. The TPX2-Aurora A heterodimer binds and counteracts Tumor Protein P53 Binding Protein 1 (53BP1) activity to stabilize and protect stalled DNA replication forks that occur in the setting of DNA damage [3]. It does this at least in part through recruitment of Breast Cancer 1 (BRCA1) and RAD51 Recombinase (RAD51). TPX2 depletion results in an accumulation of cells in mitosis and it is required for the synthesis and phosphorylation of p53 in Xenopus oocytes [4,5,6,7].

TPX2 is broadly implicated in oncogenesis in diverse solid organ malignancies, where increased levels of TPX2 mRNA typically correlates with unfavorable prognosis [8,9,10,11,12]. A large network analysis of gene expression profiles derived from two large human breast cancer cohorts and multiple mouse models of metastatic disease identified a conserved genetic signature involving TPX2 which was associated with distant metastases and worse survival [13]. TPX2 has been strongly implicated in the survival of genomically unstable cancers and targeting of TPX2 in cancer cell lines leads to mitotic arrest and increased genomic instability [14, 15]. In breast cancers, TPX2 mRNA levels have been reported as a strong predictor of aggressive behavior, reduced response to therapy, and poor survival, while depletion of TPX2 can suppress proliferation and promote apoptosis [16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. However, to our knowledge, a large immunohistochemistry (IHC)-based study of TPX2 protein expression has not been performed in primary breast cancers.

Chromosomal instability (CIN) occurs when cells randomly gain or lose whole chromosomes or large segments of chromosomes during mitosis, and along with microsatellite instability is one of the primary forms of genomic instability found in cancer [23, 24]. The presence of CIN strongly correlates with poor prognosis in solid tumors and is linked to the acquisition of resistance to chemotherapy [25, 26]. Unfortunately, measuring CIN in patient tumors requires the manual scoring of multi-centromere fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) across at least 100 tumor cells, a laborious process which is challenging to implement in routine clinical practice. In an effort to develop tractable methods to measure CIN in the clinic, we and others have utilized publicly available RNAseq datasets generated from patient-derived tumors to identify individual genes whose expression is linked to CIN [25, 27]. Out of all measured transcripts, expression of the gene TPX2 was found to be the most highly correlated to CIN.

Here we perform TPX2 IHC on a cohort of 253 patient-derived breast cancers and correlate these findings with available clinical, pathological, and molecular findings. We find that increased TPX2 nuclear expression is significantly associated with tumor grade, clinical stage, estrogen receptor (ER) status, progesterone receptor (PR) status, and both disease-specific and overall survival. Furthermore, we evaluate the relationship between TPX2 nuclear expression and genomic instability by comparing TPX2 nuclear expression levels to CIN, ploidy, centrosome number, and TP53 mutational status. We find that increased TPX2 nuclear expression is significantly associated with higher average ploidy, increased rates of centrosome amplification, and a greater incidence of TP53 mutation. However, while TPX2 expression correlates with CIN in univariate analyses, it is not independently predictive of CIN when analyzed alongside available clinical and pathologic markers. Finally, we show that increased TPX2 nuclear expression strongly correlates with survival, but its predictive power in this setting is not independent of Ki67. Together, our results demonstrate the strong correlation between TPX2 expression and both molecular and clinical metrics of aggressive disease and poor clinical outcome, while also arguing that TPX2 IHC is not an appropriate standalone assay for the determination of CIN in human tumor samples.

Methods

Tissue microarray and IRB approval

The breast cancer tissue microarray (TMA) used in this study has been reported previously [28,29,30]. Briefly, the samples were obtained from primary Stage I-III breast tumor blocks obtained at the time of surgery from patients being treated at University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center under protocol OS10111. Creation of the de-identified TMA and clinical data set were approved by the University of Wisconsin Health Sciences Institutional Review Board (IRB approval 2010–0405). The IRB waived patient consent. All cases contain at least 5 years of clinical follow-up or documented death or recurrence within 5 years. Linked clinical data included age at diagnosis, ethnicity, tumor size, lymph node involvement, stage, Ki67 index, estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and HER2 status, type of surgery, adjuvant breast cancer treatments, and follow-up data including recurrence and death. In addition, immunohistochemistry for Ki67 had been performed using a clinically validated antibody and automated scoring was performed using Vectra software. A total of 253 formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded patient-derived breast cancers with triplicate 0.6 mm punches were evaluated for the purposes of this study. These were derived from a total of 324 patient-derived breast cancers. After evaluation by a pathologist, 30 of these cases were determined to represent sampling of in situ disease and were not analyzed. An additional 41 cases could not be evaluated due to tissue loss during processing.

Immunohistochemistry and scoring

Unstained 5 μm-thick sections were stained with anti-TPX2 (Millipore-Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and anti-p53 (Clone DO-7, Roche, Basel, Switzerland) antibodies using the Ventana Discovery XT BioMarker Platform (Ventana, Tucson, AZ, USA). The anti-p53 antibody is clinically validated, while the anti-TPX2 antibody has been utilized in diverse tissue types [31,32,33,34]. For the anti-TPX2 antibody, deparaffinization and heat-based epitope retrieval were carried out on the instrument with buffer CC1 (Ventana #950–500) for 60 min at 100 °C. Anti-TPX2 was diluted 1:100 in Renaissance Background Reducing Agent diluent (BioCare Medical #PD905H) and incubated for 60 min at 37 °C. Sections were rinsed with Reaction Buffer (Ventana #950–300) and then incubated with Discovery OmniMap anti-Rabbit HRP (Ventana #760–4311) for 16 min at 37 °C. Sections were rinsed with Reaction Buffer and developed with Discovery ChromoMap DAB detection (Ventana #760–159), then counterstained with hematoxylin. Staining with the anti-p53 antibody was performed in a similar manner with the following exceptions: epitope retrieval was performed for 44 min, primary antibody incubation was performed for 28 min, and UltraMap anti-Ms HRP was applied for 8 min.

TPX2 and p53 stained TMAs were scored by a pathologist (DRM) in a blinded manner. All available tissues cores were scored for each tumor and the average score across all cores was used for analyses. For TPX2, the percent of malignant cells with positive nuclear or cytoplasmic staining as well as the intensity of nuclear and cytoplasmic staining were scored. Intensity was scored on a scale from 0 to 3: 0 = completely negative, 1 = blush or dim, 2 = moderate diffuse or heterogeneous, 3 = strong and diffuse. For p53, the percent of positive nuclei were scored. Tumors were considered to have an aberrant p53 IHC pattern if the percent of p53-positive cells was < 1% or greater than 90%. This yielded a 25% rate of TP53 mutation, which is consistent with previously reported rates of TP53 mutation in large cohorts of primary breast tumors [35]. Centrosome number had been previously quantified using anti-pericentrin (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and anti-polyglutamylated tubulin (Adipogen, San Diego, CA, USA) antibodies [29]. Centrosomes were quantified in at least 30 cells per tumor by blinded observers.

Chromosome instability

Measurements of chromosome instability (CIN) had been performed previously [29]. Briefly, chromosomes 3, 4, 7, 9, 10, and 17 were probed by FISH and chromosome numbers per cell were quantified by blinded observers in at least 10 cells per tumor. Ploidy was determined by the average combined number of all probes per cell. CIN was calculated as the average number of cells that deviated from the modal number for each analyzed chromosome. Samples were considered to have CIN if this value exceeded 45%, which yielded an appropriate ratio of CIN to non-CIN tumors.

Statistical methods

Statistics and survival analyses were performed in GraphPad PRISM version 8 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) with multivariate analyses performed in R v4.0.3 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Comparisons of TPX2 nuclear expression with age, tumor grade, clinical stage, histology, receptor status, and regional lymph node expression were analyzed using X2. When appropriate, post-hoc testing of X2 tests was performed via partitioning and Fisher’s exact test. Comparisons of nuclear TPX2 expression with CIN, mutated TP53, ploidy, and centrosome number were performed using ANOVA and post-hoc testing was performed using Tukey’s multiple comparisons testing. Overall survival was plotted using the Kaplan-Meier method. Statistical significance of disease-specific survival and overall survival were analyzed using log-rank (Mantel-Cox) testing.

Results

Distribution of TPX2 across human breast cancers

Utilizing a publicly available cohort of 105 primary human breast cancers within The Cancer Genome Atlas for which both genome-wide RNAseq and quantitative proteomics data were available, we confirmed the significant and previously-reported positive correlation between TPX2 RNA expression and TPX2 protein levels (Supplemental Figure 1A) [36, 37]. IHC for TPX2 was then performed on three TMA slides collectively representing 253 patient-derived primary breast cancers with linked pathological and clinical parameters (Table 1). All patients were female with a median age of 55 years. The majority of tumors had ductal histology (81%) with a smaller subset of lobular carcinomas (8%) and a mixture of less common histologic subtypes. Tumors represented a mix of Grade 1 (21%), Grade 2 (43%), and Grade 3 (36%) histology. Most tumors were ER-positive (80%) and PR-positive (71%), and a small subset were HER2-positive (17%). All clinical stages were represented with most tumors derived from Stage 1 (40%) or Stage 2 (48%) disease and a smaller number of Stage 3 (12%) cases. Lymph node metastases were present at diagnosis in 41% of patients. Recurrences occurred in 22% of patients and 15% of patients died due to breast cancer.

The percentage of cells with positive TPX2 staining in the cytoplasm and/or nucleus were quantified across all tumors. The average intensity of TPX2 staining was also scored using a 4-point scale (0-negative, 1-low, 2-intermediate, 3-high). We found that the intensity of TPX2 staining was strong in virtually all tumors that demonstrated any level of TPX2 expression, and that TPX2 staining intensity did not correlate with any clinicopathologic parameters (data not shown). The percentage of cells with cytoplasmic TPX2 expression was largely bimodal, with most tumors showing either a complete lack of cytoplasmic TPX2 or essentially all cells demonstrating cytoplasmic TPX2 staining, although approximately 20% of tumors displayed only partial cytoplasmic TPX2 expression (Fig. 1a). The percentage of cells with TPX2 nuclear expression showed a more nuanced distribution which ranged from 0 to 67% (Fig. 1b). We found no significant correlation between cytoplasmic and nuclear TPX2 expression (Pearson r = − 0.12 and P = 0.065). We next stratified the TPX2 nuclear expression data into categories which would be more amenable to pathological scoring in routine surgical pathology practice and meaningfully separate the tumors into groups for comparison. To this end, we chose levels of low (≤5%), intermediate (> 5% and ≤ 10%), and high (> 10%) which were utilized for all statistical analyses (Fig. 1c).

a Histogram depicting percent of cells with TPX2 cytoplasmic expression in all scored tumors. b, Histogram depicting percent of all cells with TPX2 nuclear expression in all scored tumors. c, Representative images depicting H&E and TPX2 IHC from tumors with low, intermediate, and high TPX2 nuclear expression (magnification: 100X, insets 400X)

TPX2 nuclear expression and Clinicopathologic parameters

We first sought to determine whether there were significant differences in clinicopathologic parameters across tumors with low, intermediate, and high TPX2 nuclear expression. We found that increased TPX2 nuclear expression showed a significant correlation with higher tumor grade, higher clinical stage, negative ER status, and negative PR status (Table 2). TPX2 nuclear expression showed no significant correlation with patient age at diagnosis, tumor histology, HER2 receptor status, or the presence of lymph node metastases at the time of diagnosis. In contrast to nuclear TPX2, cytoplasmic TPX2 expression did not correlate with any of the analyzed clinicopathologic parameters.

TPX2 nuclear expression and tumor proliferation

Under normal biological conditions, TPX2 plays at least two cell-cycle specific roles to ensure timely cell proliferation: 1) it regulates mitotic spindle assembly and 2) it regulates the response to DNA damage during S-phase. Therefore, we sought to determine if increased expression of TPX2 correlated with markers of cell proliferation, including tumor size and Ki67 index. We found that TPX2 nuclear expression correlated with an increase in tumor size, with larger tumors demonstrating higher TPX2 nuclear expression (Fig. 2a). TPX2 nuclear expression also showed a striking correlation with increased Ki67 index which was statistically significant across all groups (Fig. 2b). Follow up linear regression analysis confirmed a highly significant, positive correlation between TPX2 nuclear expression and Ki67 index (Supplemental Figure 1B).

a Tumor size versus TPX2 nuclear expression. b, Ki67 index versus TPX2 nuclear expression. c, Average number of centrosomes per cell versus TPX2 nuclear expression. d, Percent of tumors with aberrant p53 immunohistochemical staining versus TPX2 nuclear expression. e, Average ploidy versus TPX2 nuclear expression. f, Percentage of tumors with CIN versus TPX2 nuclear expression. *P < 0.0001, **P < 0.005

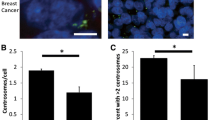

TPX2 nuclear expression and CIN

TPX2 mRNA shows the highest correlation with CIN among all detected RNA transcripts across multiple solid tumors, including primary human breast cancers [25, 27]. We therefore asked if TPX2 nuclear expression as measured by IHC correlated with known drivers of CIN. One mechanism that can bring about spindle assembly defects is centrosome amplification (CA), in which supernumerary centrosomes drive asymmetric cell divisions and cause chromosome segregation errors in mitosis [38,39,40]. TPX2 is critical for assembly of the mitotic spindle, which ensures the accurate segregation of chromosomes during mitosis. Spindle assembly defects lead to the random loss or gain of whole chromosomes or large portions of chromosomes secondary to defective mitoses, which is the hallmark of CIN. We had previously scored this tumor cohort for CA by performing immunofluorescence for the bona fide centrosome markers pericentrin and polyglutamylated tubulin, and then enumerating centrosome number in a blinded fashion across at least 30 cells in each tumor. We found that tumors with higher TPX2 nuclear expression tended to have a higher incidence of CA, although only the difference between low and high TPX2 nuclear expression was statistically significant (Fig. 2c).

Another mechanism that can facilitate CIN is loss of p53 function and TP53 is among the most mutated genes in breast cancer [41,42,43,44]. Thus, we sought to compare TPX2 nuclear expression with TP53 mutational status. Although it was not possible to sequence the TP53 gene in all 253 patient samples, IHC for p53 is a proxy for its mutational status, as most deleterious mutations in TP53 typically cause complete loss or destabilization of p53 protein expression, leading to an “all or nothing” IHC staining pattern. Because this pattern has not been formally demonstrated to be a proxy for TP53 mutation in breast cancer, we instead refer to these tumors as having “aberrant p53 IHC” [45]. We found that tumors with intermediate or high TPX2 nuclear expression showed a significantly higher rate of aberrant TP53 IHC compared to tumors with low TPX2 nuclear expression (Fig. 2d).

We sought additional evidence that tumors with elevated TPX2 expression demonstrate an increased incidence of p53 mutation, and analyzed the provisional invasive breast carcinoma cohort within the The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [46, 47]. Within this cohort of 499 tumors with RNAseq datasets, we compared the tumors with pathogenic TP53 mutations to tumors in which TPX2 mRNA expression levels were greater than 1.5 standard deviations above the mean (Supplemental Figure 1C). This demonstrated a highly significant co-occurrence of TP53 mutations with TPX2 mRNA overexpression (P < 0.001).

Finally, we sought to determine whether TPX2 nuclear expression correlated with CIN itself. We had previously scored the entire cohort for CIN using the gold standard method of CIN analysis, which involves enumerating centromeric FISH probes for loss or gain of chromosomes across at least 10 nuclei per tumor [29]. This approach also allows for the determination of ploidy. Tumors with intermediate and high TPX2 nuclear expression had an elevated ploidy compared to the low TPX2 nuclear expression group, however post-hoc testing revealed that this correlation is only statistically significant between the low and high TPX2 nuclear expression groups (Fig. 2e). In a univariate analysis, tumors with intermediate and high TPX2 nuclear expression also showed elevated incidence of CIN compared to tumors with low TPX2 nuclear expression (Fig. 2f).

To determine whether the power of TPX2 nuclear expression to predict CIN was independent of relevant clinical and pathologic parameters, two linear regression models were fit. The first model adjusted for TPX2, TP53 mutational status, Ki67, ploidy, average centrosome number per cell, and the age of the patient. Because one of the purposes of our study was to identify a modality to predict CIN independent of measuring ploidy, a second model was also fitted which omitted ploidy. In both models, TPX2 was found to have no significant independent association with CIN (P = 0.64 and P = 0.89 respectively). A graphical analysis of the residuals suggested no significant departure from model assumptions. However, given that CIN is a continuous proportion naturally bounded by 0 and 1, beta regression was also considered. In both model settings (with and without adjusting for ploidy), TPX2 nuclear expression was again found not to be independently associated with CIN (P = 0.49 and P = 0.93 respectively).

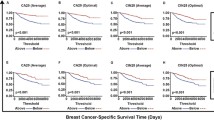

TPX2 nuclear expression and survival

We sought to determine whether TPX2 nuclear expression correlated with disease-specific survival (DSS) and/or overall survival (OS) using log-rank (Mantel-Cox) testing. This revealed that TPX2 nuclear expression significantly correlates with both DSS (P < 0.005) and OS (P < 0.0001), with lower levels of TPX2 expression correlating with improved survival (Fig. 3a and b). However, a Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for age of diagnosis and Ki67 showed that the predictive value of TPX2 on survival is not independent of Ki67 (P = 0.789). Moreover, at least some of the relationship between TPX2 and survival is reflected by the enrichment of triple negative breast cancers within the TPX2 high group (Supplemental Figure 1D and Supplemental Table 1). As expected, when compared to ER+ or HER2+ breast cancers within our cohort, the triple negative breast cancers displayed a higher pathologic grade, higher clinical stage, higher frequency of CIN, higher frequency of aberrant TP53 IHC, higher Ki67 index, higher average ploidy, and higher average centrosome number (Supplemental Tables 1 and 2). Not surprisingly, they also showed worse DSS and OS (Supplemental Figure 1E and F).

Discussion

Numerous studies have identified TPX2 RNA levels as broadly predictive of aggressive behavior, reduced response to therapy, and poor survival across multiple solid malignancies, including breast cancer [16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. Additionally, depletion of TPX2 can suppress proliferation and promote apoptosis [17]. We and others have shown that TPX2 mRNA transcripts are the most predictive of CIN in breast cancers and other solid malignancies [25, 27]. In this study, we sought to compare TPX2 protein expression levels to a broad set of clinicopathologic parameters in a large patient-derived cohort of primary breast cancers. Our findings demonstrate that TPX2 nuclear expression broadly correlates with markers of aggressive behavior, genetic instability, and poor clinical outcome.

Given that the most studied role for TPX2 is in mitotic spindle assembly, a process that begins outside of the nucleus prior to nuclear envelope breakdown, we were surprised that there was very little variability in cytoplasmic TPX2 levels within our cohort and that TPX2 cytoplasmic expression levels did not correlate with any clinicopathologic parameters. However, it should be noted that the spindle assembly function of TPX2 takes place only during the brief period of mitosis, and that only a small minority of tumor cells will be in mitosis at any given time. Thus, we were not able to specifically evaluate TPX2 levels in mitotic cells. On the other hand, we were also surprised by the wide variability in nuclear TPX2 expression across our cohort and how strongly this correlated with markers of tumor aggression and poor outcome. The reasons for this are not immediately clear, as the roles of nuclear TPX2 are only now being elucidated. However, the recent discovery that TPX2 plays a critical role in resolving stalled DNA replication forks that occur in the setting of DNA damage provides a potential explanation [3]. Loss of TPX2 in this context compromises DNA end resection, BRCA1 recruitment, and homologous recombination, and triggers replication fork instability. Thus, increased TPX2 nuclear expression may enable a more robust response to DNA damage and enable more cells to successfully traverse S-phase. We propose that future studies examine whether low TPX2 nuclear expression is predictive of radiation response in breast cancer.

We find that TPX2 nuclear expression is significantly associated with several mechanisms implicated in the genesis of CIN. One mechanism that can promote CIN is supernumerary centrosomes, and our findings indicate that cells with high nuclear TPX2 have a greater number of centrosomes per cell. This is interesting, as TPX2 is known to assist in centrosome clustering and thus its increased expression could enable cell survival in the presence of centrosome amplification [48]. We also analyzed the relationship between p53 mutational status and TPX2 nuclear expression, because loss of p53 is hypothesized to enable the development of CIN [41,42,43]. Activation of TP53 also triggers transcriptional repression of many cell cycle related genes via the dimerization partner, RB-like, E2F and multi-vulval class B (DREAM) complex, of which TPX2 is a target [49]. Because we lacked the resources to sequence the TP53 gene across all tumors in this large cohort, we instead utilized p53 IHC as a practical but imperfect surrogate. We found that increased TPX2 nuclear expression strongly correlated with an aberrant p53 IHC pattern that supports TP53 mutation in these tumors. This finding was supported by data from the TCGA, in which tumors with elevated TPX2 RNA showed a similar correlation with TP53 mutation. It is unclear why TPX2 RNA levels in the TCGA correlated with nuclear and not cytoplasmic TPX2 protein levels by IHC. However, these findings suggest that TP53 mutation may lead to DREAM complex misregulation and increased TPX2 expression. Together with the centrosome amplification data, we hypothesize that early TP53 mutation may lead to an upregulation in TPX2 levels, which ultimately correlates with genomic instability. Alternatively, overexpression of TPX2 may reduce mitotic fidelity, and further cellular proliferation in this setting is facilitated by loss of p53 function.

Finally, we find that while TPX2 nuclear expression correlates with CIN in univariate analyses, it is not independently predictive of CIN when Ki67, TP53 mutation, average centrosome number, patient age, and/or ploidy are included in the analysis. It is thus unlikely that TPX2 IHC will have practical utility in identifying tumors with CIN. The strong TPX2 correlation with Ki67 suggests that higher TPX2 nuclear expression could instead be a generic marker of higher proliferative rate, which is itself associated with CIN. Given the increasing prevalence of next-generation sequencing (NGS) data associated with newly-diagnosed patient tumors, we believe that future studies should focus on elucidating CIN status from NGS datasets.

An additional limitation of this study is that it does not assess directness of the observed correlations. Nevertheless, this is a large study directly comparing well-localized TPX2 expression with outcomes and clinicopathologic parameters in a well-characterized cohort of breast cancer subjects with long-term follow up.

Conclusions

Increased TPX2 nuclear expression identified by IHC can enable the identification of breast cancers with poor clinical behavior, elevated proliferative rate, high incidence of pathologic TP53 mutations, and greater genomic complexity. However, it is not independently predictive of CIN. The higher rate of proliferation and genomic instability in tumors with high TPX2 nuclear expression may explain why this marker is associated with poor clinical behavior in this and other studies.

Availability of data and materials

TPX2 and p53 immunohistochemical scoring is available from the author upon reasonable request. Linked clinical and pathological information for the utilized TMAs is available from the University of Wisconsin Translational Science Biocore biobank.

Abbreviations

- 53BP1:

-

Tumor Protein P53 Binding Protein 1

- BRCA1:

-

Breast Cancer 1

- CIN:

-

Chromosomal instability

- ER:

-

Estrogen receptor

- DSS:

-

Disease-specific survival

- HER2:

-

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemistry

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PR:

-

Progesterone receptor

- RAD51:

-

RAD51 Recombinase

- TCGA:

-

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- TMA:

-

Tissue microarray

- TPX2:

-

Targeting Protein for Xenopus Kinesin Like Protein 2

References

Kufer TA, Silljé HHW, Körner R, Gruss OJ, Meraldi P, Nigg EA. Human TPX2 is required for targeting Aurora-a kinase to the spindle. J Cell Biol. 2002 Aug 19;158(4):617–23.

Neumayer G, Belzil C, Gruss OJ, Nguyen MD. TPX2: of spindle assembly, DNA damage response, and cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014 Aug;71(16):3027–47.

Byrum AK, Carvajal-Maldonado D, Mudge MC, Valle-Garcia D, Majid MC, Patel R, et al. Mitotic regulators TPX2 and Aurora a protect DNA forks during replication stress by counteracting 53BP1 function. J Cell Biol. 2019 Feb 4;218(2):422–32.

De Luca M, Lavia P, Guarguaglini G. A functional interplay between Aurora-a, Plk1 and TPX2 at spindle poles: Plk1 controls centrosomal localization of Aurora-a and TPX2 spindle association. Cell Cycle. 2006;5(3):296–303.

Gruss OJ, Wittmann M, Yokoyama H, Pepperkok R, Kufer T, Silljé H, et al. Chromosome-induced microtubule assembly mediated by TPX2 is required for spindle formation in HeLa cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2002 Nov;4(11):871–9.

Garrett S, Auer K, Compton DA, Kapoor TM. hTPX2 is required for normal spindle morphology and centrosome integrity during vertebrate cell division. Curr Biol. 2002 Dec 10;12(23):2055–9.

Pascreau G, Eckerdt F, Lewellyn AL, Prigent C, Maller JL. Phosphorylation of p53 is regulated by TPX2-Aurora a in Xenopus oocytes. J Biol Chem. 2009 Feb 27;284(9):5497–505.

Sillars-Hardebol AH, Carvalho B, Tijssen M, Beliën JAM, de Wit M, Delis-van Diemen PM, et al. TPX2 and AURKA promote 20q amplicon-driven colorectal adenoma to carcinoma progression. Gut. 2012;61(11):1568–75.

Grover A, Singh R, Shandilya A, Priyandoko D, Agrawal V, Bisaria VS, et al. Ashwagandha derived withanone targets TPX2-Aurora a complex: computational and experimental evidence to its anticancer activity. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e30890.

Ma Y, Lin D, Sun W, Xiao T, Yuan J, Han N, et al. Expression of targeting protein for xklp2 associated with both malignant transformation of respiratory epithelium and progression of squamous cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006 Feb 15;12(4):1121–7.

Li B, Qi X-Q, Chen X, Huang X, Liu G-Y, Chen H-R, et al. Expression of targeting protein for Xenopus kinesin-like protein 2 is associated with progression of human malignant astrocytoma. Brain Res. 2010 Sep 17;1352:200–7.

Warner SL, Stephens BJ, Nwokenkwo S, Hostetter G, Sugeng A, Hidalgo M, et al. Validation of TPX2 as a potential therapeutic target in pancreatic cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2009 Nov 1;15(21):6519–28.

Hu Y, Wu G, Rusch M, Lukes L, Buetow KH, Zhang J, et al. Integrated cross-species transcriptional network analysis of metastatic susceptibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012 Feb 21;109(8):3184–9.

van Gijn SE, Wierenga E, van den Tempel N, Kok YP, Heijink AM, Spierings DCJ, et al. TPX2/Aurora kinase a signaling as a potential therapeutic target in genomically unstable cancer cells. Oncogene. 2019;38(6):852–67.

Hsu C-W, Chen Y-C, Su H-H, Huang G-J, Shu C-W, Wu TT-L, et al. Targeting TPX2 suppresses the tumorigenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells resulting in arrested mitotic phase progression and increased genomic instability. J Cancer. 2017;8(8):1378–94.

Yang K, Gao J, Luo M. Identification of key pathways and hub genes in basal-like breast cancer using bioinformatics analysis. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:1319–31.

Chen M, Zhang H, Zhang G, Zhong A, Ma Q, Kai J, et al. Targeting TPX2 suppresses proliferation and promotes apoptosis via repression of the PI3k/AKT/P21 signaling pathway and activation of p53 pathway in breast cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;507(1–4):74–82.

Tang J, Kong D, Cui Q, Wang K, Zhang D, Gong Y, et al. Prognostic genes of breast Cancer identified by gene co-expression Network analysis. Front Oncol. 2018;8:374.

Aushev VN, Lee E, Zhu J, Gopalakrishnan K, Li Q, Teitelbaum SL, et al. Novel Predictors of Breast Cancer Survival Derived from miRNA Activity Analysis. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(3):581–91.

Huang C, Han Z, Wu D. Effects of TPX2 gene on radiotherapy sensitization in breast cancer stem cells. Oncol Lett. 2017 Aug;14(2):1531–5.

Yang Y, Li D-P, Shen N, Yu X-C, Li J-B, Song Q, et al. TPX2 promotes migration and invasion of human breast cancer cells. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2015 Dec;8(12):1064–70.

Endesfelder D, Burrell R, Kanu N, McGranahan N, Howell M, Parker PJ, et al. Chromosomal instability selects gene copy-number variants encoding core regulators of proliferation in ER+ breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2014;74(17):4853–63.

Danielsen HE, Pradhan M, Novelli M. Revisiting tumour aneuploidy - the place of ploidy assessment in the molecular era. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016 May;13(5):291–304.

Roylance R, Endesfelder D, Gorman P, Burrell RA, Sander J, Tomlinson I, et al. Relationship of extreme chromosomal instability with long-term survival in a retrospective analysis of primary breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2011 Oct;20(10):2183–94.

Carter SL, Eklund AC, Kohane IS, Harris LN, Szallasi Z. A signature of chromosomal instability inferred from gene expression profiles predicts clinical outcome in multiple human cancers. Nat Genet. 2006 Sep;38(9):1043–8.

Duesberg P, Stindl R, Hehlmann R. Origin of multidrug resistance in cells with and without multidrug resistance genes: chromosome reassortments catalyzed by aneuploidy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001 Sep 25;98(20):11283–8.

Pfister K, Pipka JL, Chiang C, Liu Y, Clark RA, Keller R, et al. Identification of Drivers of Aneuploidy in Breast Tumors. Cell Rep. 2018;23(9):2758–69.

Wang L, Zhao Z, Meyer MB, Saha S, Yu M, Guo A, et al. CARM1 methylates chromatin remodeling factor BAF155 to enhance tumor progression and metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2014 Jan 13;25(1):21–36.

Denu RA, Zasadil LM, Kanugh C, Laffin J, Weaver BA, Burkard ME. Centrosome amplification induces high grade features and is prognostic of worse outcomes in breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2016 Jan 29;16:47.

Choudhary A, Zachek B, Lera RF, Zasadil LM, Lasek A, Denu RA, et al. Identification of selective Lead compounds for treatment of high-Ploidy breast Cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2016 Jan;15(1):48–59.

Yan L, Li S, Xu C, Zhao X, Hao B, Li H, et al. Target protein for Xklp2 (TPX2), a microtubule-related protein, contributes to malignant phenotype in bladder carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2013 Dec;34(6):4089–100.

Zou J, Huang R-Y, Jiang F-N, Chen D-X, Wang C, Han Z-D, et al. Overexpression of TPX2 is associated with progression and prognosis of prostate cancer. Oncol Lett. 2018 Sep;16(3):2823–32.

Wei P, Zhang N, Xu Y, Li X, Shi D, Wang Y, et al. TPX2 is a novel prognostic marker for the growth and metastasis of colon cancer. J Transl Med. 2013 Dec 17;11:313.

Jiang P, Shen K, Wang X, Song H, Yue Y, Liu T. TPX2 regulates tumor growth in human cervical carcinoma cells. Mol Med Rep. 2014 Jun;9(6):2347–51.

Olivier M, Langer√∏d A, Carrieri P, Bergh J, Klaar S, Eyfjord J, et al. The clinical value of somatic TP53 gene mutations in 1,794 patients with breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(4):1157–67.

Tang W, Zhou M, Dorsey TH, Prieto DA, Wang XW, Ruppin E, et al. Integrated proteotranscriptomics of breast cancer reveals globally increased protein-mRNA concordance associated with subtypes and survival. Genome Med. 2018;10(1):94.

Johansson HJ, Socciarelli F, Vacanti NM, Haugen MH, Zhu Y, Siavelis I, et al. Breast cancer quantitative proteome and proteogenomic landscape. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1600.

Lingle WL, Lutz WH, Ingle JN, Maihle NJ, Salisbury JL. Centrosome hypertrophy in human breast tumors: implications for genomic stability and cell polarity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998 Mar 17;95(6):2950–5.

Pihan GA, Purohit A, Wallace J, Knecht H, Woda B, Quesenberry P, et al. Centrosome defects and genetic instability in malignant tumors. Cancer Res. 1998 Sep 1;58(17):3974–85.

Ghadimi BM, Sackett DL, Difilippantonio MJ, Schröck E, Neumann T, Jauho A, et al. Centrosome amplification and instability occurs exclusively in aneuploid, but not in diploid colorectal cancer cell lines, and correlates with numerical chromosomal aberrations. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2000;27(2):183–90.

Burds AA, Lutum AS, Sorger PK. Generating chromosome instability through the simultaneous deletion of Mad2 and p53. PNAS. 2005 Aug 9;102(32):11296–301.

Carroll PE, Okuda M, Horn HF, Biddinger P, Stambrook PJ, Gleich LL, et al. Centrosome hyperamplification in human cancer: chromosome instability induced by p53 mutation and/or Mdm2 overexpression. Oncogene. 1999 Mar;18(11):1935.

Donehower LA, Godley LA, Aldaz CM, Pyle R, Shi YP, Pinkel D, et al. Deficiency of p53 accelerates mammary tumorigenesis in Wnt-1 transgenic mice and promotes chromosomal instability. Genes Dev. 1995 Apr 1;9(7):882–95.

Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2012;490(7418):61–70.

Watanabe G, Ishida T, Furuta A, Takahashi S, Watanabe M, Nakata H, et al. Combined immunohistochemistry of PLK1, p21, and p53 for predicting TP53 status: an independent prognostic factor of breast Cancer. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39(8):1026–34.

Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, et al. The cBio Cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional Cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012 May 1;2(5):401–4.

Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, Sumer SO, et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal. 2013 Apr 2;6(269):pl1.

Leber B, Maier B, Fuchs F, Chi J, Riffel P, Anderhub S, et al. Proteins required for centrosome clustering in cancer cells. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2(33):33ra38.

Engeland K. Cell cycle arrest through indirect transcriptional repression by p53: I have a DREAM. Cell Death Differ. 2018 Jan;25(1):114–32.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Stephanie McGregor for her assistance with histologic subtyping, the University of Wisconsin Translational Research Initiatives in Pathology laboratory for assistance with histology and IHC, and Colin Longhurst and the staff of the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center Biostatistics Shared Resource for assistance with statistical analyses.

Funding

The authors thank the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at the University of Wisconsin Hospitals and Clinics for financial support for material costs and service costs of immunohistochemistry. DRM also received salary support from the University of Wisconsin-Madison Kirschstein National Research Service Award (T32 HL07899). PTS received support for materials and analysis of CIN by a grant from the The Women’s 4 Miler Breast Care Fund at the University of Virginia Cancer Center. Histology work performed by the University of Wisconsin Translational Research Initiatives in Pathology laboratory was supported by the University of Wisconsin Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center (P30 CA014520) and the Office of The Director – National Institutes of Health (S10OD023526). Statistical analyses by Colin Longhurst and the staff of the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center Biostatistics Shared Resource were supported by a Cancer Center Support Grant (P30 CA014520).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DRM scored the TPX2 and p53 immunohistochemistry. RAD scored centrosome number and chromosome instability. LMZ scored chromosome instability. PTS scored relationship between TP53 mutation TPX2 expression in the TCGA. DRM, RAD, LMZ, MEB, BAW, CF, and PTS analyzed the results. DRM and PTS prepared the figures. DRM, MEB, BAW, CF, and PTS wrote the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Tumors used to construct the TMAs utilized in this study were obtained from patients being treated at University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center under protocol OS10111. Creation of the de-identified TMA and clinical data set were approved by the University of Wisconsin Health Sciences Institutional Review Board (IRB approval 2010–0405). The IRB waived patient consent.

All biospecimen samples (tissue microarrays) were utilized under the University of Wisconsin – Madison’s Carbone Cancer Center’s Translational Science Biocore BioBank’s “Honest Broker” IRB protocol (Protocol 2016–0934), which allows distribution of biospecimens with coded patient data. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies involving animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

M.E.B. declares the following: Medical advisory board of Strata Oncology; Research funding from Abbvie, Genentech, Puma, Arcus, Apollomics, and Loxo Oncology. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplemental Table 1

Statistical relationships between breast cancer receptor subtype and age, tumor grade, clinical stage, tumor histology, presence or absence of lymph node metastases at the time of diagnosis, TP53 IHC results, chromosomal instability (CIN), and TPX2 IHC results. Percentages are rounded to the nearest whole number and may not sum to 100%. Supplemental Table 2 Statistical relationships between breast cancer receptor subtype and tumor size, Ki67 index, ploidy, and centrosome number.

Additional file 2: Supplemental Fig. 1 A

, Correlation between TPX2 RNA and TPX2 protein expression in 105 primary human breast cancers derived from The Cancer Genome Atlas (solid line = best fit, dashed lines = 95% CI). B, Correlation between TPX2 nuclear expression and Ki67 index in study cohort (solid line = best fit). C, Co-occurrence of pathologic TP53 mutations and TPX2 mRNA overexpression in The Cancer Genome Atlas provisional breast invasive carcinoma cohort (P < 0.001). D, Percent of estrogen receptor positive (ER+), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 positive (HER2+), and ER negative, progesterone receptor (PR) negative, and HER2 negative (triple negative) tumors within the TPX2 low, intermediate, and high groups. E, Kaplan-Meier curve showing relationship between disease-specific survival and receptor status (log rank P < 0.03). F, Kaplan-Meier curve depicting relationship between overall survival and receptor status (log rank P < 0.001).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Matson, D.R., Denu, R.A., Zasadil, L.M. et al. High nuclear TPX2 expression correlates with TP53 mutation and poor clinical behavior in a large breast cancer cohort, but is not an independent predictor of chromosomal instability. BMC Cancer 21, 186 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-021-07893-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-021-07893-7