Abstract

Background

Recent reviews have reported inconclusive results regarding the usefulness of consuming dates (Phoenix dactylifera L. fruit) in the peripartum period. Hence, this updated systematic review with meta-analysis sought to investigate the efficacy and safety of this integrated intervention in facilitating childbirth and improving perinatal outcomes.

Methods

Eight data sources were searched comprehensively from their inception until April 30, 2023. Parallel-group randomized and non-randomized controlled trials published in any language were included if conducted during peripartum (i.e., third trimester of pregnancy, late pregnancy, labor, or postpartum) to assess standard care plus oral consumption of dates versus standard care alone or combined with other alternative interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration’s Risk of Bias (RoB) assessment tools and the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) were employed to evaluate the potential RoB and the overall quality of the evidence, respectively. Sufficient data were pooled by a random-effect approach utilizing Stata software.

Results

Of 2,460 records in the initial search, 48 studies reported in 55 publications were included. Data were insufficient for meta-analysis regarding fetal, neonatal, or infant outcomes; nonetheless, most outcomes were not substantially different between dates consumer and standard care groups. However, meta-analyses revealed that dates consumption in late pregnancy significantly shortened the length of gestation and labor, except for the second labor stage; declined the need for labor induction; accelerated spontaneity of delivery; raised cervical dilatation (CD) upon admission, Bishop score, and frequency of spontaneous vaginal delivery. The dates intake in labor also significantly reduced labor duration, except for the third labor stage, and increased CD two hours post-intervention. Moreover, the intervention during postpartum significantly boosted the breast milk quantity and reduced post-delivery hemorrhage. Likewise, dates supplementation in the third trimester of pregnancy significantly increased maternal hemoglobin levels. The overall evidence quality was also unacceptable, and RoB was high in most studies. Furthermore, the intervention’s safety was recorded only in four trials.

Conclusion

More well-designed investigations are required to robustly support consuming dates during peripartum as effective and safe integrated care.

Trial registration

PROSPERO Registration No: CRD42023399626

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite the considerable scientific efforts invested in exploring effective and safe methods for childbirth progress, induction of labor (IOL) has been widely utilized when this progress is inappropriate [1]. The prevalence of IOL varies from area to area, yet this intervention is conducted in about 20% and 25% of all births in developing and developed countries, respectively [2]. Although IOL is a crucial life-saving practice that potentially prevents perinatal complications, it is not always successful [3]. Based on a recent cross-sectional study, three out of four parturients who had IOL achieved a vaginal delivery [4]. The pooled prevalence of unsuccessful IOL was also reported to be 23.58% in a systematic review; however, the magnitude of this condition depends on induction guidelines and maternal factors [5]. In addition to the risk of failed IOL, this practice could be associated with some undesired outcomes, such as longer labor stages and excessive uterine contractions, which may raise the risk of uterine rupture, postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), and birth asphyxia, as well as the need for cesarean section (C/S) and instrumental births [6]. Furthermore, IOL might lead to a substantial economic burden and inconvenience for parturients due to their restricted mobility and continuous fetal heart rate monitoring [7]. Likewise, misusing oxytocin and prostaglandins usually administered for IOL can result in adverse perinatal outcomes [8]. Thus, using safe integrative caring interventions to facilitate childbirth and improve perinatal outcomes is valuable in maternal-neonatal health nursing.

Herbal products have been one of the most used complementary methods for facilitating labor progress in many traditions because they are safer, lower-cost, and easier to access than pharmaceutical drugs [9, 10]. Many self-prescribed medicinal plants and herbs have been used globally during peripartum for safe delivery and fetus well-being, such as evening primrose, raspberry, castor bean, fennel, saffron, pennyroyal, sisymbrium, peganum, dill, chasteberry, and chamomile [11,12,13,14,15,16]. However, Phoenix dactylifera L (P. dactylifera), generally known as date palm, has attracted researchers’ interest more seriously over the past years, especially in the Middle East and Islamic Traditional Medicine [17,18,19].

The consumption of date palm fruit (DPF), commonly named dates, is a typical behavior among women from the Middle East during the final month of gestation [20]. In different traditional medicines, DPF is also highly recommended to be consumed by parturients and breastfeeding mothers [21]. Likewise, based on Islamic narrations and verses of the holy Quran (the leading Islamic religious book), eating DPF is favorably proposed in late pregnancy and labor for safe childbirth and promoting maternal and neonatal health [22, 23]. In the holy Quran, P. dactylifera was highly glorified, and its heavenly fruit was presented as a beneficial diet to the Virgin Mary when she gave birth to Prophet Issa (peace be upon him). According to hadiths, God would not have recommended DPF to Mary if it was an inappropriate food source [24]. The DPF has substantial fructose, glucose, tannins, serotonin, linoleic and linolenic fatty acids, calcium, iron, potassium, magnesium, estrogen, progesterone, potuchsin hormone, and oxytocin-like agents. These ingredients all cause satisfactory childbirth and perinatal outcomes, including but not limited to strengthening maternal energy, stimulating the uterine muscle contractions, accelerating the spontaneity of labor and uterine involution process, declining labor pain, facilitating placental abruption, increasing parturients’ hemoglobin (Hb) levels and controlling their blood pressure, reducing PPH, and boosting the mother’s breast milk production [21, 25,26,27].

Despite the scientific rationale behind the beneficial effects of eating DPF in peripartum, some trials do not robustly support this practice. It was reported that maternal cervical dilatation (CD); delivery mode; and/or the score of neonatal appearance, pulse, grimace, activity, and respiration (APGAR) did not significantly change between parturients who ingested DPF in late pregnancy or labor and those who only received routine obstetric and nursing care [28,29,30]. Besides, no substantial differences were reported in the length of labor stages between the dates consumption and control groups [28, 29, 31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. Further, the efficacy of using DPF on labor bleeding or PPH was similar to standard care [28, 29, 38, 39]. Also, there was no significant increase in maternal’ Hb levels after daily consumption of DPF [28, 40,41,42].

In addition to trials, recent systematic reviews or meta-analyses have reported contradicting findings on the usefulness of consuming DPF in late pregnancy or labor [43,44,45,46,47]. Previous studies mainly limited the publication’s searches regarding databases, languages, or locations; thus, they have missed several related trials. Additionally, the last corresponding systematic review with meta-analysis screened publications up to August 2019 [43]; however, some relevant studies have been published since then. Therefore, by performing a comprehensive search in different appropriate data sources, this updated systematic review aimed to summarize and statistically pool the results of all available non-randomized and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published in any language regarding the effects of oral intake of DPF in the peripartum period on childbirth progress and perinatal outcomes.

Methods

This review observed the last guideline of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Supplementary Table 1) [48]. The formal ethical assessment was obtained from Abadan University of Medical Sciences, Abadan, Iran (No. IR.ABADANUMS.REC.1401.164). Additionally, the protocol was documented in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO, No. CRD42023399626).

Eligibility criteria

The trials published in peer-reviewed journals in any language were eligible if they had the criteria presented in Table 1. Limitations were not considered in the inclusion criteria concerning women’s parity, gravidity, and gestational age, as well as intervention frequency, duration, and time. Moreover, if eligible articles were multiple reports of one trial with analysis of different intended study outcomes, all were retained; instead, the results were incorporated in the meta-analysis once to ignore overlapping participants.

The studies were excluded if they: 1) followed a one-group pre-test/post-test approach, 2) had insufficient data on the intervention method, 3) were a non-human study, thesis, dissertation, book chapter, review, or conference proceeding, 4) conducted intervention in the first or second trimester of gestation, 5) recruited participants aged less than 18 or more than 45 years, 6) included women with a history of high-risk pregnancy, serious antenatal problems, or severe post-delivery complications, 7) administered dates’ products in combination with other fruit-based or herbal-based remedies, or 8) used either DPF or other carbohydrate sources based on women demands, and the number of dates consumers was unclear.

Search characteristics

A comprehensive search was accomplished in three international databases (i.e., Cochrane Library, Scopus, and Web of Science Core Collection) and two search engines (i.e., PubMed and Google Scholar). Besides, a search was performed in the Scientific Content Database of the Islamic World Science Citation Center (ISC) to find further non-English publications (e.g., Persian, Arabic, or Indonesian). Also, the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT) and the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) were screened for register entries of trials. Moreover, the references of pertinent publications were hand-searched for extra related articles.

The search strategy consisted of different vocabularies and synonyms of P. dactylifera merged with related medical subject headings (MeSH) and keywords. The search syntax for each data source is available in Supplementary Table 2. First, data sources were searched during February 2023. Then, a complementary search was conducted in April 2023 to obtain new articles. The publication date was not limited to ensure all relevant trials were included. Two independent investigators (ZS, MN) performed the search, and any uncertainty or dispute between them was fixed through consensus adjudication.

Studies selection and data management

First, all retrieved records were transferred to Endnote software. Then, duplications were dismissed, and the remaining records were screened for eligibility based on titles, abstracts, and keywords. In the next step, the full text of potential eligible publications was inspected to prove their eligibility. Finally, a data extraction form was utilized to document the main details of each included trial, including authors’ names, publication date and language, study design and country of origin, participants’ characteristics, sample size, intervention protocol, control conditions, and findings (i.e., means and standard deviations [SDs] or number and percentage of intended outcomes in addition to any reported adverse effects). Besides, we extracted dates’ administration frequency, dosage, and duration for dose-response analysis. If a study did not report the consumed numbers or weights of DPF, the data were estimated based on the administration dosage presented in a similar included research; otherwise, 10-11 pieces of DPF were considered as ~ 100 grams [49]. Also, we calculated the difference between the first and last consumption times for an indefinite administration duration.

In addition to extracting the characteristics mentioned above, the quality of each trial was addressed by utilizing the Cochrane Collaboration’s Risk of Bias (RoB) assessment tools. To this end, the RoB in Non-randomized Studies-of Interventions (ROBINS-I) and the RoB2 tools were used for non-RCTs and RCTs, respectively [50, 51]. Further, criteria suggested by the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation Working Group (GRADE) were employed to judge the overall evidence quality [52].

Screening of the retrieved records and extracting the data from the included studies were performed independently by two researchers (MI, MZ). If an article contained insufficient information regarding the implemented interventions or findings, the principal author was contacted via E-mail to get the missing data. Any disagreement among the researchers was settled by in-depth discussion within the research team.

Data analysis

If at least three studies documented the same outcomes, their data were pooled through the meta-analysis. A random-effects model was utilized to compute the risk ratio (RR) or weighted mean difference (WMD) with a corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). The I-squared statistic (I2) and Cochran’s Q test were applied to show between-study heterogeneity and the degree of inconsistency [53]. Since the pooled effect sizes (ESs) were less than ten, a contour-enhanced funnel plot was not drawn for publication bias; instead, Egger’s and Begg’s tests were executed [54]. If substantial publication bias was found, the trim-and-fill technique was used. Also, to estimate the standard administration dosage and duration of DPF to bring maximum results, the non-linear dose-response analysis was applied by fractional polynomial modeling. Furthermore, other supplementary investigations (i.e., sensitivity, subgroup, or meta-regression) were employed where applicable. The statistical analyses were run using Stata, version 11.2 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA). A P < 0.05 was supposed to be significant.

Results

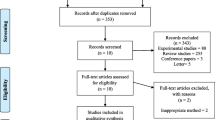

Studies screening and selection

The study identification and selection details are visualized in Supplementary Fig. 1. After screening 2,460 identified records, 33 were excluded based on full-text evaluation (Supplementary Table 3). Finally, 55 publications were considered eligible for this review. Of these, three articles represented overlapping populations; each reported a different intended outcome [55,56,57]. Two sets of publications also had such a condition [58,59,60,61]. Additionally, three articles had an identical registry code and were separate reports of a single trial [62,63,64]. Similarly, two other articles were redundant publications [65, 66]. Accordingly, a total of 48 studies, documented in 55 articles, were included in the current review.

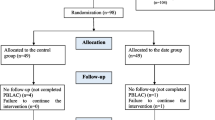

Description of the included publications

The main characteristics of the included articles are summarized in Table 2. They were published in Indonesian (n= 25), English (n= 21), or Persian (n= 9) from 2007 to March 2023. The studies were performed in Indonesia (n= 30), Iran (n= 9), Egypt (n= 2), Saudi Arabia (n= 2), Pakistan (n= 2), Jordan (n= 1), Malaysia (n= 1), and Thailand (n= 1). Fifteen trials used random allocation, and the remaining 33 studies followed a non-randomized design. Sample sizes of studies ranged from 10 to 105 per group.

Forty-three trials used a two-arm design; the remaining five had three arms. We extracted the data from the standard intervention and dates consumption groups for three three-arm studies that considered an extra group of alternative interventions, including saffron-honey syrup [58, 59], honey syrup [62,63,64], and fenugreek herbal tea [93]. The remaining two three-arm trials had the following groups: 1) DPF consumption alone, DPF consumption followed by drinking water, and control (standard care) [29], and 2) DPF syrup, placebo syrup (Saccharin tablets blended with water), and control (standard care) [85]. For these two trials, we compared the groups of DPF consumption with drinking water and DPF syrup to those of control and placebo syrup to be more consistent with other included studies conducted intervention during labor.

Thirty-six studies applied a multiple-time intervention for either 7-14 days during the third trimester of pregnancy (n= 8), 1-8 weeks in the late pregnancy (n= 15), 3-28 days in postpartum (n= 9), 90.3-166.7 minutes during labor (n= 3), or four weeks in the late pregnancy in combination with one-time intervention in childbirth (n= 1). Also, eight studies administered one intervention session during either labor (n= 5) or postpartum (n= 3). The remaining four studies conducted intervention during delivery but did not report the consumption frequency [35,36,37, 83]. The dates’ administration dosage was approximately 3-10 pieces/day (4-315 pieces in total), 40-100 grams/day (50-3,500 grams in total), 15 or 45 mL/day (88.8-1,260 mL in total). Concerning the consumed dates’ ripening stage and form, 14 trials used Tamer in either pure form (n= 12) or syrup (n= 2), and six administered Rutab in either pure form (n= 5) or juice (n= 1). Additionally, 27 studies used DPF in pure form (n= 14), juice (n= 12), or syrup (n= 1), but their ripening stage was unspecified. The remaining study did not report the ripening stage and form [88]. The dates’ varieties were reported in 22 publications; the most used was Bam Mazafati (n= 6), pursued by Sukari (n= 3) and Ajwa (n= 3).

Pooled analyses of the study outcomes

Gestation length

Four trials measured gestation duration following eating DPF in pure form during late pregnancy [28, 31, 56, 66]. Based on the meta-analysis, dates consumption had a low but significant effect on reducing gestation duration compared to the standard care (three RCTs and one non-RCT, WMD= ˗1.97 days; 95% CI [˗3.24 to ˗0.69 days]; P= 0.003). After excluding only non-RCT [31], the overall estimation stayed significant for the remaining three RCTs (Fig. 1: a). Nevertheless, sensitivity analysis revealed the dependency of the overall pooled ES on the study by Kordi et al. [56] (WMD= ˗0.78 days; 95% CI [˗2.98 to 1.41 days]) (Supplementary Fig. 2: a).

Forest plots for the effects of oral consumption of dates in late pregnancy on the duration of gestation (a), labor’s latent phase (b), labor’s active phase (c), the first labor stage (d), the second labor stage (e), and the third labor stage (f); stratified by study design (randomized controlled trial [RCT] vs. non-randomized controlled trial [non-RCT])

Duration of different stages of labor

Twenty-eight publications addressed the labor duration in either the latent phase (n= 3), active phase (n= 11), the first stage (n= 14), the second stage (n= 16), or the third stage (n= 12), as well as in total (n= 5) [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37, 39, 57, 59,60,61,62,63, 65, 75, 77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85]. Two publications had the same participants [62, 63]; hence, we excluded one with a smaller sample size from the meta-analysis [62]. Besides, the meta-analysis did not include eight other studies because they reported only categorical data (n= 6) [32, 33, 36, 37, 81, 84] or did not report the SDs (n= 2) [60, 61]. Alao, meta-analysis was not performed on two non-RCTs that reported the effectiveness of dates consumption during late pregnancy in reducing total labor duration [39, 77], considering the insufficient ESs. Hence, 17 trials were suitable for meta-analysis of labor duration.

The pooled analysis revealed that the consumption of PDF in late pregnancy compared to the standard care significantly reduced labor duration in the latent phase (two RCTs and one non-RCT, WMD= ˗213.66 min; 95% CI [˗296.01 to ˗131.31 min]; P< 0.001), the active phase (three RCTs and one non-RCT, WMD= ˗67.93 min; 95% CI [˗121.61 to ˗14.24 min]; P= 0.013), the first stage (one RCT and five non-RCTs, WMD= ˗54.96 min; 95% CI [˗79.07 to ˗30.85 min]; P< 0.001), and the third stage (three RCTs and two non-RCTs, WMD= ˗1.21 min; 95% CI [˗2.12 to ˗0.30 min]; P= 0.009); however, the intervention had a non-significant impact on reducing the duration of the second labor stage (three RCTs and two non-RCTs, WMD= ˗15.05 min; 95% CI [˗31.23 to 1.13 min]; P= 0.068). After excluding only non-RCT [31], the primary findings on the duration of latent and active phases did not change. Similarly, the efficacy of the intervention was similar in the first stage duration, excluding only RCT [75]. Concerning the second stage duration, the finding was not dependent on the study design. However, RCTs [28, 57, 75] substantially affected the overall pooled ES of the third stage duration (Fig. 1: b-f). Likewise, after excluding the trial by Rezali et al. [28], sensitivity analysis altered the non-significant result of the primary meta-analysis obtained for the second labor stage duration to significant (four ESs, WMD= ˗18.97 min; 95% CI [˗35.99 to ˗1.94 min]). Also, the overall pooled ES of the active phase duration depended on the study by Karimian et al. [65] (WMD= ˗86.42 min; 95% CI [˗177.66 to 4.81 min]). Similarly, the result of the third labor stage duration depended on the study by Kordi et al. [57] (WMD= ˗1.03 min; 95% CI [˗2.21 to 0.14 min]) (Supplementary Fig. 2: b-f).

The meta-analysis also indicated that the consuming DPF in labor compared to the control conditions significantly reduced the total duration of labor (three non-RCTs, WMD= ˗1.27 hours; 95% CI [˗1.91 to ˗0.62 hours]; P< 0.001) and labor duration in the active phase (three RCTs, WMD= ˗88.38 min; 95% CI [˗145.25 to ˗31.50 min]; P= 0.002), the first stage (one RCT and three non-RCTs, WMD= ˗66.10 min; 95% CI [˗96.58 to ˗35.61 min]; P< 0.001), and the second stage (three RCTs and three non-RCTs, WMD= ˗19.46 min; 95% CI [˗31.14 to ˗7.79 min]; P= 0.001); nevertheless, the intervention had a non-significant influence on reducing the length of the third labor stage (two RCTs and three non-RCTs, WMD= ˗2.61 min; 95% CI [˗6.10 to 0.88 min]; P= 0.068). After excluding only RCT [29], the intervention effect on the first stage duration remained substantial. Also, the overall pooled ES of the second stage duration was not dependent on the study design. However, the overall pooled ES of the third stage duration was substantially affected by RCTs because analysis of data based on non-RCTs altered the non-significant impact of the intervention to significant (Fig. 2: a-e). Similarly, after excluding the trial by Ahmed et al. [29], the intervention substantially affected the reduction of the third labor stage (four ESs, WMD= ˗3.83 min; 95% CI [˗5.10 to ˗2.57 min]). Yet, sensitivity analysis did not reveal the dependency of the overall pooled ESs obtained for other outcomes related to labor duration in a singular study (Supplementary Fig. 3: a-e).

Forest plots for the effects of oral consumption of dates in labor on the duration of total labor (a), labor’s active phase (b), the first labor stage (c), the second labor stage (d), and the third labor stage (e); and cervical dilatation two hours post-intervention (f); stratified by study design (randomized controlled trial [RCT] vs. non-randomized controlled trial [non-RCT])

Bishop score and CD

Fourteen publications reported the efficacy of consuming DPF on either Bishop score [65, 78], CD [28, 29, 31, 34, 56, 57, 62, 63, 75, 85], or both [55, 66]. Out of these, three collections of publications had similar participants; hence, their data were included in the meta-analysis once [55, 56, 62, 63, 65, 66].

Based on the pooled analysis, the CD significantly improved approximately two hours after the beginning of intervention in women who consumed DPF during labor compared with those in the standard/alternative care group (three RCTs, WMD= 0.54 cm; 95% CI [0.11 to 0.97 cm]; P= 0.014) (Fig. 2: f). Moreover, eating DPF during late pregnancy, in comparison with the standard care, could significantly increase the CD upon admission (four RCTs and one non-RCT, WMD= 1.15 cm; 95% CI [0.25 to 2.05 cm]; P= 0.012) and Bishop score (two RCTs and one non-RCT, WMD= 2.47; 95% CI [2.00, 2.94]; P< 0.001). After excluding only non-RCT, the primary findings on the CD upon admission [31] and Bishop score [78] did not change (Fig. 3: a, b). Sensitivity analysis also did not reveal the dependency of the overall pooled ESs on a particular study (Supplementary Fig. 3: f & Fig. 4: a, b).

Forest plots for the effects of oral consumption of dates in late pregnancy on cervical dilatation upon admission (a); Bishop score (b); frequency of spontaneous onset of labor (c); and frequency of need for labor induction (d); stratified by study design (randomized controlled trial [RCT] vs. non-randomized controlled trial [non-RCT])

Forest plots for the effects of oral consumption of dates in late pregnancy on the frequency of spontaneous vaginal delivery (a), need for instrumental vaginal delivery (b), and need for cesarean section delivery (c); stratified by study design (randomized controlled trial [RCT] vs. non-randomized controlled trial [non-RCT])

Status of labor onset

Ten publications reported the type of labor onset following consuming DPF in pure form during late pregnancy [28, 31, 32, 39, 55,56,57, 66, 75, 76]. Three of these were conducted on the same participants. Hence, one with a smaller sample size was excluded from the meta-analysis [57], and the remaining two publications were considered in the meta-analysis once [55, 56]. Three out of ten studies reported the significant effect of intervention in reducing the need for labor augmentation [28, 31, 75]. However, these studies were impossible to pool in the meta-analysis because one study reported the frequency of labor augmentation in combination with IOL [31].

The pooled analysis showed the significant effects of ingesting DPF in late pregnancy compared to the control conditions on increasing the frequency of spontaneous onset of labor (five RCTs and one non-RCT, RR= 1.32; 95% CI [1.11, 1.56]; P= 0.001) and reducing the frequency of need for IOL (five RCTs and two non-RCTs, RR= 0.48; 95% CI [0.39, 0.60]; P< 0.001). Excluding only non-RCT [39] could not change the primary finding of spontaneous labor occurrence. Yet, the overall pooled ES of the need for IOL was substantially influenced by RCTs (Fig. 3: c, d). Based on the sensitivity analysis, the ESs of spontaneous onset of labor and IOL did not rely on an individual study (Supplementary Fig. 4: c, d).

Delivery mode

Two studies reported a non-significant effect of dates consumption during labor on delivery mode [30, 85]. Considering the insufficient ESs, these trials were not pooled in the meta-analysis. On the other hand, eight publications reported delivery mode after consuming DPF in late pregnancy [28, 31, 39, 55, 56, 65, 66, 75]. Out of these, two collections of publications had overlapping populations; hence, their data were included in the meta-analysis once [55, 56, 65, 66].

Pooled analysis disclosed that parturients who had consumed DPF in late pregnancy had a significantly more spontaneous vaginal delivery (four RCTs and one non-RCT, RR= 1.09; 95% CI [1.01, 1.18]; P= 0.032); however, they had a non-significant lesser need for instrumental vaginal delivery (four RCTs, RR= 0.37; 95% CI [0.09, 1.46]; P= 0.154) and the C/S delivery (four RCTs and two non-RCTs, RR= 0.75; 95% CI [0.55, 1.01]; P= 0.054). After excluding only non-RCT [39], the primary finding on spontaneous vaginal delivery remained significant. Also, the study design could not affect the overall pooled ES of the C/S delivery (Fig. 4). Though, sensitivity analysis altered the non-significant effect of the intervention on C/S delivery to significant after excluding the studies by Rezali et al. [28] (five ESs, RR= 0.68; 95% CI [0.50, 0.93]) and Karimian et al. [65] (five ESs, RR= 0.66; 95% CI [0.46, 0.94]). Also, the overall ES of spontaneous vaginal delivery depended on the study by Hiba et al. [75] (four ESs, RR= 1.06; 95% CI [0.97, 1.15]) (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Breast milk production

Eight trials addressed the intervention efficacy in breast milk production, 1-90 days after delivery. Of these, four non-RCTs conducted in Indonesia evaluated the smoothness of breast milk production after the daily intake of DPF either in postpartum [87, 90, 91] or late pregnancy [74]. The remaining four trials (i.e., two RCTs and two non-RCTs) reported the breast milk quantity following the daily consumption of DPF during postpartum [49, 88, 89, 93].

Two of the eight studies were not incorporated in the meta-analysis due to methodological inconsistency with other studies [74, 93]. The pooled analysis showed the significant effects of the daily consumption of DPF during postpartum compared to the standard care on increasing changes in breast milk quantity from baseline to post-intervention (one RCT and two non-RCTs, WMD= 29.81 mL; 95% CI [7.69 to 51.94 mL]; P= 0.008). However, intervention efficiency in boosting the smoothness of breast milk production was non-significant (three non-RCTs, RR= 2.04; 95% CI [0.41, 10.13]; P= 0.381). After excluding only RCT [49], the primary finding of milk quantity did not change (Fig. 5: a, b). Also, excluding one study [91], which conducted an alternative intervention in the comparison group (i.e., drinking Katuk leaves extract), did not modify the primary finding of smoothness of milk production. Similarly, the sensitivity analysis did not show the dependency of the overall pooled ES obtained for the smoothness of milk production in a particular trial. However, the finding of breast milk quantity depended on the studies by Agustina et al. [88] (two ESs, WMD= 68.00 mL; 95% CI [˗55.97 to 191.98 mL]) and Ramadhani and Akbar [89] (two ESs, WMD= 75.98 mL; 95% CI [˗30.98 to 182.94 mL]) (Supplementary Fig. 6: a, b).

Forest plots for the effects of oral consumption of dates in postpartum on changes in breast milk quantity from baseline to post-intervention (a); the frequency of smoothness of breast milk production (b); and first-day postpartum bleeding rate (c); stratified by study design (randomized controlled trial [RCT] vs. non-randomized controlled trial [non-RCT])

Bleeding rate

Four trials reported the labor bleeding rate after consuming DPF in late pregnancy [28, 39, 82] or labor’s active phase [29]. Since only two studies reported quantitative information [29, 82], data were unsuitable for the meta-analysis. However, none of these studies showed the potential effect of intervention in reducing the labor bleeding rate, except for one non-RCT [82].

Five trials also evaluated the postpartum bleeding rate following eating DPF in the postpartum [38, 86, 94, 95] or late pregnancy [81]. Of these, one non-RCT, which conducted an intervention in late pregnancy, was not incorporated in the meta-analysis [81]. Accordingly, ESs of the other four trials reported the bleeding rate during the first day after natural childbirth were pooled through the meta-analysis. The finding indicated the significant effect of eating DPF in pure form nearly after placenta delivery compared to the standard care (e.g., oxytocin injection) on reducing postpartum bleeding rate (four RCTs, WMD= ˗30.91 mL; 95% CI [˗53.98 to ˗7.83 mL]; P= 0.009) (Fig. 5: c). However, the sensitivity analysis exhibited the dependency of the overall pooled ES on the study by Niknami et al. [86] (three ESs, WMD= ˗38.75 mL; 95% CI [˗80.45 to 2.94 mL]) (Supplementary Fig. 6: c).

Maternal Hg levels

Eight non-RCTs in Indonesia evaluated Hb levels before and after the daily intake of DPF in pure or juice forms for 7-14 days in the third trimester of pregnancy [41, 67,68,69,70,71,72,73]. Additionally, one RCT showed no significant effect of the intervention in late pregnancy on maternal Hb status before and after delivery [28]; however, this was not incorporated in the meta-analysis, considering methodological inconsistency with the abovementioned studies.

According to the pooled analysis, supplementation with DPF and iron tablets in the third trimester of pregnancy led to more an increase in changes of Hb levels from baseline to post-intervention than consumption of iron tablets alone among parturients with mild/moderate pregnancy-related anemia (eight non-RCTs, WMD= 0.93 gr/dl; 95% CI [0.55 to 1.32 gr/dl]; P< 0.001) (Fig. 6). The sensitivity analysis did not reveal the dependence of the overall pooled ES on an individual study (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Labor pain severity

Four publications evaluated the benefit of consuming DPF during the labor’s active phase on alleviating pain severity induced in the labor’s active phase alone [29, 62, 64] or labor’s active phase in addition to the second and third labor stages [58]. Two publications had the same participants [62, 64], and one did not report quantitative pain values and between-group differences [29]. Hence, performing a meta-analysis was impossible due to insufficient ESs. However, two RCTs showed a more significant reduction of labor pain after drinking DPF syrup during labor than the control conditions [58, 64].

Uterine contractions

Three studies evaluated the indices of uterine contractions (i.e., frequency, intensity, or regularity) after eating DPF in either late pregnancy [32] or labor [29, 34]. Two studies found no significant between-group differences [29, 32]. In contrast, the remaining one reported a significantly higher frequency and intensity of uterine contractions in women who consumed seven pieces of DPF in the first labor stage compared with those who only received standard care [34]. Running a meta-analysis was impossible due to data inconsistency.

Fetal, neonatal, or infant indices

Eight studies documented the fetal, neonatal, or infant outcomes, including the APGAR score (n= 5), neonatal birth weight (n= 3), infant weight gain (n= 3), fetal presentation (n= 2), fetal heart rate (n= 1), admission rate to neonatal intensive care ward (n= 1), and presence of meconium- or blood-stained liquor (n= 1) [28,29,30, 34, 56, 65, 76, 92]. Only two of five studies that measured the APGAR score displayed quantitative data [29, 65]. Similarly, two out of three studies reported quantitative values for birth weight [56, 65]. Also, we observed a methodological inconsistency among three studies on infant weight gain [49, 92, 93]. Hence, we could not pool the related data through meta-analysis. Nonetheless, most outcomes were not significantly different between dates consumer and standard care groups.

Adverse effects

Of four RCTs that addressed the adverse effects of intervention with consuming DPF, no side effects have been reported [28, 38, 55, 85].

Subgroup and meta-regression analyses

There was no between-study heterogeneity for Bishop score (I2= 0.0%, Fig. 3: b), frequency of need for IOL (I2= 0.0%, Fig. 3: d), and frequency of spontaneous vaginal delivery (I2= 0.0%, Fig. 4: a). Also, between-study heterogeneity was low-to-moderate for gestation length (I2= 9.6%, Fig. 1: a), duration of labor’s latent phase (I2= 27.5%, Fig. 1: b), duration of third labor stage (intervention time: late pregnancy, I2= 28.8%, Fig. 1: f), total duration of labor (I2= 48.7%, Fig. 2: a), first labor stage duration (I2= 27.2%, Fig. 2: c), and frequency of need for C/S delivery (I2= 8.8%, Fig. 4: c). Nonetheless, high heterogeneity was discovered between studies for other study outcomes.

Based on the subgroup analysis, the study design might be a source of heterogeneity for the third labor stage duration (intervention time: labor, Fig. 2: e). In addition, this analysis suggested that the observed heterogeneity in the study outcomes could be due to differences in other variables, including the women’s gestational age at recruitment and their parity; the study’s country of origin, publication language, and methodological quality; the number of study arms; the comparison condition; and the dates’ administration form, ripening stage, and variety. Also, based on the subgroup results, some of the above variables were significantly associated with more changes in the study outcomes (Supplementary Table 4).

In addition to subgroup analysis, meta-regression was performed for continuous variables, including dates’ administration duration and dosage, as well as the study’s publication date and total sample size. According to the meta-regression, none of the mentioned variables was a heterogeneity source and was considerably associated with differences in the study outcomes, except for dates’ administration dosage, which had a significant association with changes in the length of the first and second labor stages (Supplementary Table 5).

Dose-response analysis

Performing the dose-response analysis was suitable for labor duration, CD upon admission, and maternal Hb level. According to the results of this analysis, a significant inverse association was found between the changes in the duration of the second labor stage and the total consumption dosage of DPF when the intervention was performed during labor (P-nonlinearity: consumed number= 0.013, consumed weight= 0.016) (Supplementary Fig. 8). However, the link between the dates’ administration dosage and/or duration and differences in the length of labor in the first, second, and third stages was not dose-dependent when the intervention was accomplished in late pregnancy (Supplementary Figs. 9-11). Such a finding was also revealed for the third labor stage duration when the intervention was conducted during labor (Supplementary Fig. 12). Also, the relation between the consumption dosage and duration of DPF and the differences in the CD upon admission and maternal Hb level was not dose-dependent (Supplementary Figs. 13 and 14).

Publication bias

Based on the results of Egger’s test, an asymmetry was disclosed for the pooled ESs of spontaneous onset of labor (P= 0.003) and the smoothness of breast milk production (P= 0.026). Nonetheless, applying the trim-and-fill technique could not modify the ESs of these outcomes, implying that publication bias did not influence the obtained results. Also, no publication bias was seen for other study outcomes according to Egger’s and Begg’s tests (Supplementary Table 6).

The evidence quality and risk of bias

According to the Cochrane RoB2 tool, four RCTs had a low RoB for all criteria [28, 75, 85, 86]. However, other RCTs had unacceptable methodological quality, primarily due to concerns arising from the randomization process and high or unclear RoB in selecting the reported result (Supplementary Figs. 15, 16 & Supplementary Table 7). In addition, the overall quality of most non-RCTs was low based on the ROBINS-I, mainly due to high RoB in confounding, high or unclear RoB in the classification of interventions, and unclear RoB in the selection of the reported result (Supplementary Figs. 17, 18 & Supplementary Table 8). Likewise, the evidence quality was low or moderate in most outcomes based on the GRADE method. The leading reasons for diminishing the evidence rate were serious RoB and inconsistency (Supplementary Table 9).

Discussion

Maternal health needs continuous effort as it could substantially affect society and the family’s health [97]. Commonly, parturients have used self-prescribed herbal remedies during peripartum, especially in low-income and upper-middle-income regions; however, the safety and effectiveness of this complementary intervention are still challenging [11]. Despite the widespread utilization of DPF as a natural supplement for its beneficial properties during peripartum, some potential drawbacks are reported regarding this caring approach [98]. Also, review studies supporting the effects of oral consumption of DPF on facilitating childbirth were mostly narrative or systematic, making an evidence-based conclusion impossible [23, 46, 47, 99,100,101,102]. Furthermore, previous meta-analyses have reported contradictory results regarding the potential effects of administrating DPF on perinatal outcomes [43,44,45]. Hence, the routine use of this practice in childbirth and perinatal care has remained questionable. Therefore, believing the highest rank of systematic reviews on the clinical evidence hierarchy [103], we conducted this updated systematic review with meta-analysis to augment the previous reviews regarding the safety of oral intake of DPF during the peripartum period and the efficacy of this integrated intervention in facilitating childbirth and improving perinatal outcomes.

Based on meta-analysis findings, administering DPF in postpartum increased breast milk production and reduced PPH more than routine interventions. Likewise, supplementation with DPF in the third trimester of gestation raised the parturients’ Hb level. A literature review showed no meta-analyses evaluating the efficacy of eating DPF on these outcomes. Nevertheless, the findings substantiated the earlier related systematic reviews. Two recent systematic reviews showed that DPF could increase the smoothness of breastfeeding and breastfeeding adequacy in postpartum mothers [104, 105]. Besides, in a systematic review of three RCTs, favorable evidence was documented for the usefulness of DPF in decreasing PPH [106]. Likewise, two reviews showed an effect of giving DPF on raising Hb levels in parturients with mild anemia [107, 108].

Based on the present meta-analysis, parturients with low-risk gestation consuming DPF in late pregnancy had significantly shorter latent and active phases and the first and third labor stages; nevertheless, they had a non-significant trend toward shortened the second labor stage. On the other hand, the administration of DPF during labor significantly reduced the labor length in the first and second stages and the active phase, while it had a non-significant impact on shortening the third labor stage. Based on the sensitivity analysis results, the non-significant findings could be due to the dependency of the overall estimate on an individual study. In other words, ignoring the RCT of Rezali et al. [28] changed the non-significant effect of consuming DPF during late pregnancy on declining the second labor stage length to significant. Similarly, excluding the RCT of Ahmed et al. [29], we found the intervention efficacy during labor concerning shortening the third labor stage duration.

The findings mentioned above updated the available systematic reviews that support the effect of DPF on minimizing childbirth duration [46, 47, 100]. However, previous meta-analyses have reported controversial results regarding labor duration. In a meta-analysis of three studies (i.e., one RCT, one quasi-RCT, and one non-RCT) published in English between 2011-2017, Sagi-Dain and Sagi indicated that women consuming DPF in late pregnancy had a significantly shorter latent phase (two ESs, MD= ˗275.56 min, P= 0.005) and the second labor stage (two ESs, MD= ˗7.66 min, P= 0.0005); however, they experienced no significant decline in time of active phase (three ESs, MD= ˗86.43 min, P= 0.06) and the third labor stage (three ESs, MD= ˗0.98 min, P= 0.09) [45]. The findings of the mentioned study are inconsistent with our results, except for shortening the latent phase duration. On the other, in a meta-analysis of five studies (i.e., four RCTs and one quasi-RCT) published in English and Persian until 2018, Bagherzadeh Karimi et al. demonstrated the significantly reducing effect of oral supplementation with DPF in late pregnancy and labor on the duration of active phase (three ESs, MD= ˗109.30 min, P= 0.01); nevertheless, the intervention had non-significant effects on shortening the first labor stage (two ESs, MD= ˗76.16 min, P= 0.22) and the second labor stage (four ESs, MD= ˗6.41 min, P= 0.44), as well as it did not reduce the third labor stage (three ESs, MD= 0.39 min, P= 0.82) [43]. The study described above evaluated the intervention efficacy during both late pregnancy and labor, which might lead to bias because their subgroup analyses based on the administration time during late pregnancy changed the significant effect of the intervention on reducing the active phase duration to non-significant (two ESs, MD= ˗125.39 min, P= 0.15). In contrast, it changed the non-impact of intervention on lowering the third stage duration to significant (two ESs, MD= ˗1.42 min, P= 0.03), which is consistent with the finding of the present study. In another meta-analysis of eight publications in Persian and English, Nasiri et al., as the first attempt, showed that consuming DPF significantly shortened the first labor stage duration (five ESs, MD= ˗65.24 min, P= 0.009); yet, its effects were non-significant on diminishing the length of second labor stage (four ESs, MD= ˗11.27 min, P= 0.193) and the third labor stage (three ESs, MD= ˗0.98 min, P= 0.089) [44]. The study described above combined the data of studies that performed interventions during late pregnancy and labor; hence, it is impossible to compare this study’s findings with ours.

The discrepancies between the findings of the meta-analyses mentioned above and the current meta-analysis on the labor duration could be attributed to the number and design of included trials and different study objectives. In the present review, we obtained 15 RCTs and 38 non-RCTs published in English, Indonesian, and Persian until April 2023, using a comprehensive search of different data sources. Hence, more ESs were pooled for each study outcome compared to previous meta-analyses. Also, we analyzed data based on the intervention time as a leading confounding parameter. However, as mentioned earlier, only one of the previous meta-analyses considered the intervention time as a criterion for including studies [45], one another performed a subgroup analysis based on intervention time [43], and the remaining one overlooked intervention time as a variable for inclusion or subgroup analysis [44].

Based on the present meta-analysis, women consuming DPF in late pregnancy were experienced a significantly lower gestation length, admitted with a substantially higher CD, had a considerably higher Bishop score and spontaneous onset of labor, and encountered a significantly lower rate of IOL. Likewise, the intervention significantly increased the frequency of spontaneous vaginal delivery, while it did not significantly reduce the need for instrumental vaginal delivery and C/S. However, based on the sensitivity analysis, the non-significant effect of the intervention on the frequency of C/S changed to significant after excluding two trials (i.e., Rezali et al. [28] and Karimian et al. [65]). Similar to our findings, a meta-analysis showed that consuming DPF in late pregnancy significantly increased CD upon admission (three ESs, MD= 1.10 cm, P= 0.02) and decreased the need for IOL and/or augmentation (three ESs, RR= 0.60, P= 0.002); however, it had a non-significant impact on lowering the C/S rate (three ESs, RR= 0.70, P= 0.20) [45]. Another meta-analysis also demonstrated that DPF had a considerable effect on the progress of the Bishop score (two ESs, MD= 2.45, P< 0.00001), yet it had a non-significant reducing effect regarding the C/S frequency (three ESs, RR= 0.80, P= 0.23) [43]. Besides, a meta-analysis showed that eating DPF significantly shortened gestation length (four ESs, MD= ˗0.30 days, P< 0.001) and increased CD on admission (five ESs, MD= 1.03 cm, P= 0.022) [44]. However, a meta-analysis of herbal drugs regarding the spontaneous onset of labor reported the non-significant effect of eating DPF in late pregnancy, using subgroup analysis (three ESs, RR= 1.05, P= 0.45) [14]. We pooled data from six studies on the spontaneous onset of labor; hence, the observed difference could be due to a higher number of pooled ESs in the current study.

Implications for clinical practice and research

This meta-analysis revealed the usefulness of consuming DPF orally in the third trimester of pregnancy, late pregnancy, labor, or postpartum for the parturients or breastfeeding mothers. Our study suggests that using DPF had significant small-to-moderate effects on the reduction in the need for IOL and post-delivery bleeding; while at the same time improving the spontaneity of labor, the occurrence of spontaneous vaginal delivery, CD, Bishop score, breast milk volume, and maternal Hb levels. Also, the findings indicated that consuming DPF could significantly shorten gestation and labor, especially by the 213-minute shortening of the latent phase when considered in late pregnancy. Moreover, it can non-significantly decrease the frequency of instrumental vaginal delivery and C/S, as well as boost the smoothness of breast milk production. Accordingly, since consuming DPF is an easy, low-cost, non-pharmacological complementary intervention and DPF is readily obtainable in most regions and easily transportable, these effects are noteworthy in maternal-neonatal health nursing, especially in situations where little care might be available. However, there are some concerns about reaching a reliable conclusion on using this herbal remedy alone or in combination with other routine interventions for improving perinatal care.

The first concern is a lack of well-designed trials on the subject. Out of 48 studies, only four RCTs were deemed of excellent methodological quality. The subgroup analyses also indicated that the intervention was more efficacious in low-quality studies regarding increasing the CD upon admission and spontaneous onset of labor, as well as reducing the labor duration in the third and second stages. Moreover, the quality of evidence varied from low to moderate for most outcomes based on the GRADE approach. Accordingly, future trials with improved methodological quality should be conducted and reported rigorously based on the accepted guidelines. Since observing the effects of the intervention on fetal, neonatal, or infant indices as well as uterine contractions and labor pain severity was impossible using meta-analysis due to the restricted number of related trials, further investigations regarding these outcomes are deserved. Also, given the non-significant effects of the intervention on reducing the labor duration in the second and third stages following administrating DPF during late pregnancy and labor, respectively, as well as declining the frequency of instrumental vaginal and C/S deliveries, and boosting the smoothness of breast milk production, further studies on these outcomes are warranted. Moreover, since the included studies were conducted in Asia or the Middle East countries, where DPF is a staple in the daily regime, performing related trials in populations that do not regularly consume large amounts of DPF would provide more reliable information about how consumption of DPF can affect the study outcomes.

The second concern is the lack of a standard for dates’ administration dosage, duration, form, time, and cultivar to provide maximum results. Most manuscripts did not mention the dates’ variety and ripening stage. However, the chemical composites of different cultivars of dates could differ depending on climate, planting site, tree age, and fruit growth approach [21]. Also, the sweetness and ingredients of DPF in the Tamer and Rutab ripening stages are substantially different [96]. On the other hand, the included studies mainly examined the effectiveness of consuming 6-7 pieces of DPF per day (60-80 grams/day) in pure form during the last month of pregnancy. Previous meta-analyses suggested the consumption of DPF for 1-4 weeks during the late pregnancy, beginning from 36-38 weeks of pregnancy, as an intriguing option [43, 45]. Concerning the optimal intervention time, we found no significant impacts of the intervention on reducing the duration of the second labor stage following administrating DPF in late pregnancy. In contrast, the intervention during labor significantly reduced this stage’s length. Such conflicting findings were also observed for the duration of the third labor stage. Also, according to the subgroup analyses, we revealed that the intervention was more efficacious in the third labor stage duration (intervention time: late pregnancy), gestation length, CD upon admission, and spontaneous onset of labor in the studies conducted on women with a gestational age of more than or equal to 37 weeks, which might be due to more substantial number of included trials recruited women with this condition. Additionally, we found contradictory findings about the dates’ administration form. The intervention in late pregnancy remarkably declined the duration of the first labor stage in the investigations that administered DPF in pure form. However, the length of the first labor stage was more reduced after consuming DPF during labor in studies that used the pure form of DPF followed by drinking water. Also, the length of the second labor stage decreased more seriously when the juice form of DPF was administered during labor, whereas eating DPF in pure form might significantly increase maternal Hb levels. Regarding the dates’ administration variety, we found that gestation length was better reduced when Bam Mazafati was consumed.

Based on the dose-response estimations, the optimal amount and number of DPF to observe its maximum impact on lowering the length of the second labor stage were 200-700 grams and six pieces when administered during labor. However, we found no precise dosage or optimal duration of DPF for its impacts on other study outcomes. These findings could be due to the limited pooled ESs and low variations in the administration dosages and durations of DPF used in the included studies. Therefore, to reach evidence-based conclusions, further studies should evaluate the effects of oral intake of DPF during different periods, especially late pregnancy and labor, using different administration dosages, durations, forms, and varieties. Also, it is of merit to examine the impacts of consuming DPF at crucial periods, such as during prolonged labor and post-term pregnancies (i.e., beginning at 40 weeks of gestation), as well as among parturients with term pre-labor rupture of membranes. Additionally, it is suggested to evaluate the potential effect of DPF consumption before 37 weeks of gestation to induce preterm labor.

Another point of concern is the scarcity of safety data. Out of the 48 included studies, only four evaluated the adverse effects of the intervention. Although eating DPF was reported to be safe and free of side effects for the mother or the infant, the safety of this practice, especially in late pregnancy, is still questionable. In a review of the effectiveness of different botanical parts of dates, the authors declared treatment safety in obstetrics [109]. Nevertheless, the daily intake of DPF by parturients might be relatively troublesome, particularly in those with pre-gestational or gestational diabetes, due to the high amounts of sugar in DPF [45]. Besides, consuming more than two pieces of DPF at a time is assumed to substantially increase parturients’ blood glucose levels [98]. However, some studies documented that clients with diabetes can use DPF surely as it does not lead to immediate and meaningful changes in blood glucose; it may even benefit glycaemic and lipid control [110, 111]. Considering the controversial reports on adverse effects of DPF, it must be consumed in a specified dosage and duration and under the supervision of a high-qualified therapeutic team (e.g., maternity nurses, obstetricians, midwives, and dieticians). Also, forthcoming trials must measure laboratory parameters to ensure using DPF as a safe integrative care in the peripartum period.

Strengths and novelty

The present review is the first dose-response meta-analysis performed to estimate the standard dosage and duration of DPF that must be administered to achieve ultimate results. Additionally, we investigated the effects of consuming DPF for the first time through a meta-analysis approach regarding the need for assisted vaginal delivery, frequency of spontaneous vaginal delivery, PPH, breast milk quantity and the smoothness of milk production, and maternal Hg level. Also, we used the last version of the Cochrane RoB tool for appraising the RCTs’ methodological quality; however, two previous meta-analyses utilized the old version of the Cochrane RoB assessment tool [43, 45], and one employed the Jadad scale [44]. Besides, we applied GRADE to assess the evidence quality, whereas only one previous meta-analysis used this approach regarding three included studies [45]. Unlike previous meta-analyses that combined the findings of studies with different designs (i.e., RCT, quasi-RCT, and non-RCT), we stratified data for RCTs and non-RCTs. Likewise, we categorized and analyzed data based on the consumption time of DPF, which was dismissed in two previous meta-analyses [43, 44]. Moreover, we summarized and statistically pooled the findings of all available studies published in any language, employing a broad search in diverse data sources.

Limitations

First, in some outcomes, high heterogeneity was found in the pooled analyses, and the evidence quality was low or moderate, which could limit evidence-based conclusions. Second, only four studies recorded the adverse effects of intervention; therefore, the available data need to be expanded to reach valid conclusions about the safety of consuming DPF in peripartum. Third, some studies did not report the consumption dosages and durations of DPF. Although we requested further information from the studies’ authors, no reply was acquired in some cases; hence, estimations were made based on the researchers’ consensus. Fourth, performing a dose-response analysis was impossible in all issues because of the restricted number of included studies and the anonymous information on intervention dosages and durations. Fifth, given the limited pooled ESs, performing the meta-regression and subgroup analyses was sometimes impossible. Finally, due to the limited number of studies, we could not estimate the pooled effects of the intervention on fetal, neonatal, or infant indices, as well as uterine contractions and labor pain severity.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis showed the benefits of eating DPF by parturients or breastfeeding mothers in the third trimester of pregnancy, late pregnancy, labor, or postpartum. The findings indicated that the administration of DPF could potentially shorten the duration of gestation and childbirth, decline the need for IOL, accelerate the spontaneity of delivery, raise CD and Bishop score, augment the frequency of spontaneous vaginal delivery, boost the breast milk quantity, reduce PPH, and improve maternal Hb levels. However, the intervention had non-significant but favorable impacts regarding the frequency of instrumental vaginal delivery, C/S, and the smoothness of breast milk production. Additionally, this study revealed a paucity of trials documenting the adverse effects of intervention with DPF and a scarcity of high-quality studies on the issue. Accordingly, to confirm the impacts of consuming DPF on childbirth and perinatal outcomes, additional studies with enhanced methodological quality are required to meticulously assess the adverse effects of intervention and estimate the safety laboratory indices. Moreover, exploring the exact dosage of DPF and the optimal intervention duration to obtain the maximum beneficial impacts on the study outcomes is of merit.

Availability of data and materials

Data and materials are available by contacting the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- APGAR:

-

Appearance, pulse, grimace, activity, and respiration

- CD:

-

Cervical dilatation

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- C/S:

-

Cesarean section

- DPF:

-

Date palm fruit

- ES:

-

Effect sizes

- GRADE:

-

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation Working Group

- Hb:

-

Hemoglobin

- I2 :

-

I-squared statistic

- ICTRP:

-

International Clinical Trials Registry Platform

- IOL:

-

Induction of labor

- IRCT:

-

Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials

- ISC:

-

Scientific Content Database of the Islamic World Science Citation Center

- MeSH:

-

Medical subject headings

- PPH:

-

Postpartum hemorrhage

- PROSPERO:

-

International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses

- RCTs:

-

Randomized controlled trials

- RoB:

-

Risk of bias

- ROBINS-I:

-

Risk of bias in Non-randomized Studies-of Interventions

- RR:

-

Risk ratio

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- WMD:

-

Weighted mean difference

References

Nunes I, Dupont C, Timonen S, Ayres de Campos D, Cole V, Schwarz C, et al. European guidelines on perinatal care - Oxytocin for induction and augmentation of labor. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022;35(25):7166–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2021.1945577.

Assemie MA, Mihiret GT, Mekonnen C, Petrucka P, Getaneh T, Ashebir W. Outcomes and associated factors of induction of labor in East Gojjam Zone, Northwest Ethiopia: A multicenter cross-sectional study. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2023;2023:6910063. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/6910063.

Debelo BT, Obsi RN, Dugassa W, Negasa S. The magnitude of failed induction and associated factors among women admitted to Adama hospital medical college: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2022;17(1):e0262256. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0262256.

Farah FQ, Aynalem GL, Seyoum AT, Gedef GM. The prevalence and associated factors of success of labor induction in Hargeisa maternity hospitals, Hargeisa Somaliland 2022: a hospital-based cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023;23(1):437. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-023-05655-w.

Melkie A, Addisu D, Mekie M, Dagnew E. Failed induction of labor and its associated factors in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon. 2021;7(3):e06415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06415.

Kazi S, Naz U, Naz U Sr, Hira A, Habib A, Perveen F. Fetomaternal outcome among the pregnant women subject to the induction of labor. Cureus. 2021;13(5):e15216. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.15216.

Kamel R, Garcia FSM, Poon LC, Youssef A. The usefulness of ultrasound before induction of labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2021;3(6s):100423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100423.

Bouchghoul H, Zeino S, Houllier M, Senat MV. Cervical ripening by prostaglandin E2 in patients with a previous cesarean section. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2020;49(4):101699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogoh.2020.101699.

Fukunaga R, Morof D, Blanton C, Ruiz A, Maro G, Serbanescu F. Factors associated with local herb use during pregnancy and labor among women in Kigoma region, Tanzania, 2014–2016. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):122. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-2735-3.

Karimian Z, Sadat Z, Afshar B, Hasani M, Araban M, Kafaei-Atrian M. Predictors of self-medication with herbal remedies during pregnancy based on the theory of planned behavior in Kashan Iran. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2021;21(1):211. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-021-03353-8.

Zamawe C, King C, Jennings HM, Mandiwa C, Fottrell E. Effectiveness and safety of herbal medicines for induction of labour: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8(10):e022499. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022499.

Gohari H, Rahmani R, Rahmani Bilandi R. Effect of evening primrose on cervical ripening: a systematic review study (Persian). J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2020;30(191):155–65.

Eddouks M, Hebi M, Ajebli M. Medicinal plants and gyneco-obstetric disorders among women in the South East of Morocco. Curr Women’s Health Rev. 2020;16(1):2–17. https://doi.org/10.2174/1573404815666191206112518.

Ghasemi M, Ebrahimzadeh-Zagami S, Ghavami V. [The effect of outpatient herbal drugs on cervical ripening and onset of labor: a systematic review and meta-analysis (Persian)]. J Isfahan Med Sch. 2022;39(655):999–1009. https://doi.org/10.22122/jims.v39i655.14232.

Ivari FR, Vatanchi AM, Yousefi M, Badaksh F, Salari R. Edible medicinal plants on facilitating childbirth: a systematic review. Curr Drug Discov Technol. 2022;19(2):e240921196771. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570163818666210924115650.

Rahmanian SA, Irani M, Aradmehr M. [The effect of medicinal plants on gynecological and obstetric hemorrhages: a systematic review of clinical trials (Persian)]. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2022;25(7):113–27. https://doi.org/10.22038/ijogi.2022.21139.

Abdi F, Torabi A, Ahangar Khorasani A, Atarodi Kashani Z, Takfallah R. Effect of date on delivery stages and pregnancy outcomes from the medical, holy Quran and hadiths point of view (Persian). Quran Med. 2022;7(3):57–69.

Sedighi-Khavidak S, Shekarbeygi N, Delfani M, Haidar Nejad F. Nutritional and medicinal values of dates (Phoenix Dactylifera L.) from the perspective of modern medicine and Iranian traditional medicine. Complement Med J. 2022;12(1):44–55. https://doi.org/10.32598/cmja.12.1.1101.2.

Kushi EN, Belachew T, Tamiru D. Importance of palm’s heart for pregnant women. J Nutr Sci. 2023;12:e5. https://doi.org/10.1017/jns.2022.112.

Arabiat D, Whitehead L, Gaballah S, Nejat N, Galal E, Abu Sabah E, et al. The use of complementary medicine during childbearing years: a multi-country study of women from the Middle East. Glob Qual Nurs Res. 2022;9:23333936211042616. https://doi.org/10.1177/23333936211042616.

Al-Snafi A, Thuwaini M. Phoenix dactylifera: Traditional uses, chemical constituents, nutritional benefit and therapeutic effects. Tradit Med Res. 2023;8(4):20.

Namazi Zadegan S, Ghayour-Mobarhan M, Hasheminejad SO, Shamsoddin Dayani M. [Effects of eating frankincense, dates and quince during pregnancy and lactation on the mood, mental and behavioral health of children according to the Quran, Hadith and Medical Sciences (Persian)]. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2018;20(11):93–105. https://doi.org/10.22038/ijogi.2018.10232.

Shaikh ML, Patel MF, Chaudhry AR, Mulla G, Chaudhry RA. Effect of consumption of date fruit in late pregnancy-A review in Islamic and scientific perspective. Adv J AYUSH Res. 2020;1(1):28–32.

Hosseini Karnamy SH, Asghari Velujayi AA. Evaluation of the effects of date palm on childbirth based on the scientific interpretation of verses 26–23 of Surah Maryam (As) in the holy Quran (Persian). Relig Health. 2016;3(2):29–40.

Saryono M, Rahmawati E. Effects of dates fruit (Phoenix dactylifera L.) in the female reproductive process. Int J Recent Adv Multidiscip Res. 2016;3(7):1630–3.

Mahomoodally MF, Khadaroo SK, Hosenally M, Zengin G, Rebezov M, Ali Shariati M, et al. Nutritional, medicinal and functional properties of different parts of the date palm and its fruit (Phoenix dactylifera L.) - A systematic review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2023:Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2023.2191285.

Naureen I, Saleem A, Rana NJ, Ghafoor M, Ali FM, Murad N. Potential health benefit of dates based on human intervention studies: a brief overview. Haya Saudi J Life Sci. 2022;7(3):101–11. https://doi.org/10.36348/sjls.2022.v07i03.006.

Razali N, Mohd Nahwari SH, Sulaiman S, Hassan J. Date fruit consumption at term: Effect on length of gestation, labour and delivery. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;37(5):595–600. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443615.2017.1283304.

Ahmed IE, Mirghani HO, Mesaik MA, Ibrahim YM, Amin TQ. Effects of date fruit consumption on labour and vaginal delivery in Tabuk. KSA J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2018;13(6):557–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtumed.2018.11.003.

Al-Dossari A, Ahmad ER, Al Qahtani N. Effect of eating dates and drinking water versus IV fluids during labor on labor and neonatal outcomes. IOSR J Nurs Health Sci. 2017;6(4):86–94. https://doi.org/10.9790/1959-0604038694.

Al-Kuran O, Al-Mehaisen L, Bawadi H, Beitawi S, Amarin Z. The effect of late pregnancy consumption of date fruit on labour and delivery. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;31(1):29–31. https://doi.org/10.3109/01443615.2010.522267.

Azizah G, Mappaware NA, Pramono SD, Hamsah M, Karsa NS. Comparative analysis of the childbirth process in mothers (inpartu) who consuming and those who do not consuming Ajwa dates (Phoenix dactylifera L) (Indonesian). Fakumi Med J. 2023;3(2):98–105.

Addini LAP, Titisari I, Wijanti RE. [The influence of giving dates on the progress of labor in the 2nd stage of labor in Aura Syifa Hospital, Kediri District (Indonesian)]. Jurnal Kebidanan Kestra (JKK). 2020;2(2):126–34. https://doi.org/10.35451/jkk.v2i2.340.

Zaher EH, Khedr NFH, Fadel EA. Effect of eating date fruit on the progress of labor for parturient women. Int J Novel Res Healthc Nurs. 2021;8(3):188–96.

Mutiah C. [The effect of giving palm juice (Dactilifera Phoenix) to first-time mothers on the duration of labor in the work area of Langsa Baro Health Center (Indonesian)]. Jurnal SAGO Gizi dan Kesehatan. 2019;1(1):29–34. https://doi.org/10.30867/gikes.v1i1.285.

Pongoh A, Budi NK, Dawam SA. The effect of giving date palm juice on the duration of the first stage of labor in Sele Be Solu Hospital, Sorong City. Medico-Legal Update. 2020;20(3):893–8. https://doi.org/10.37506/mlu.v20i3.1515.

Jayanti ID. [Duration of first stage active phase of mother maternity who consume palm extract and sugar water (Indonesian)]. Oksitosin. 2014;1(1):13–7.

Yadegari Z, Akbari SAA, Sheikhan Z, Nasiri M, Akhlaghi F. The effect of consumption of the date fruit on the amount and duration of the postpartum bleeding (Persian). Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2016;18(181):20–7.

Kuswati K, Handayani R. Effect of dates consumption on bleeding, duration, and types of labor. J Midwifery. 2019;4(1):85–91.

Jannah M, Puspaningtyas M. [Increasing Hb levels of pregnant women with dates palm juice and green bean juice in Pekalongan (Indonesian)]. PLACENTUM. 2018;6(2):1–6. https://doi.org/10.13057/placentum.v%vi%i.22518.

Sugita S, Kuswati K. [The effect of consumption of dates on increasing hemoglobin levels in third trimester pregnant women (Indonesian)]. Jurnal Kebidanan dan Kesehatan Tradisional. 2020;5(1):58–66. https://doi.org/10.37341/jkkt.v5i1.138.

Sendra E, Pratamaningtyas S, Panggayuh A. [The effect of consumption of dates (Phoenix Dactylifera) on increased hemoglobin levels in trimester II pregnant women at the Kediri Health Center (Indonesian)]. Jurnal Ilmu Kesehatan. 2016;5(1):96–104. https://doi.org/10.32831/jik.v5i1.119.

Bagherzadeh Karimi A, Elmi A, Mirghafourvand M, Baghervand Navid R. Effects of date fruit (Phoenix dactylifera L.) on labor and delivery outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-02915-x.

Nasiri M, Gheibi Z, Miri A, Rahmani J, Asadi M, Sadeghi O, et al. Effects of consuming date fruits (Phoenix dactylifera Linn) on gestation, labor, and delivery: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Complement Ther Med. 2019;45:71–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2019.05.017.

Sagi-Dain L, Sagi S. The effect of late pregnancy date fruit consumption on delivery progress - A meta-analysis. Explore (NY). 2021;17(6):569–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.explore.2020.05.014.

Ulya Y, Siskha Maya H, Yopi Suryatim P. Date juice accelerates labor in the first stage. J Qual Public Health. 2022;5(2):613–8. https://doi.org/10.30994/jqph.v5i2.287.

Azizah N, Abdullah RPI, Wello EA. The effect of consumption Ajwa dates (Phoenix Dactylifera L.) on the duration of the first stage of labor. Green Med J. 2022;4(1):9–15.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

Modepeng T, Pavadhgul P, Bumrungpert A, Kitipichai W. The effects of date fruit consumption on breast milk quantity and nutritional status of infants. Breastfeed Med. 2021;16(11):909–14. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2021.0031.

Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i4919.

Sterne JAC, Savovic J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4898.

Schünemann H, Borzek J, Connor P, Oxman A. GRADE handbook: Introduction to GRADE handbook: The GRADE Working Group; 2013. Available from: https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/handbook/handbook.html.

Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.3 (updated February 2022): The Cochrane Collaboration; 2022. Available from: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current.

Lin L, Chu H. Quantifying publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2018;74(3):785–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/biom.12817.

Kordi M, Aghaei Meybodi F, Tara F, Nemati M, Taghi Shakeri M. The effect of late pregnancy consumption of date fruit on cervical ripening in nulliparous women. J Midwifery Reprod Health. 2014;2(3):150–6. https://doi.org/10.22038/jmrh.2014.2772.

Kordi M, Aghaei Meybodi F, Tara F, Nematy M, Shakeri MT. [The effect of date consumption in late pregnancy on the onset of labor in nulliparous women (Persian)]. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2013;16(77):9–15. https://doi.org/10.22038/ijogi.2013.2101.

Kordi M, Meybodi FA, Tara F, Fakari FR, Nemati M, Shakeri M. Effect of dates in late pregnancy on the duration of labor in nulliparous women. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2017;22(5):383–7. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijnmr.IJNMR_213_15.

Sohrabi H, Karimeh R, Ghaderkhani G, Shahoei R. [The effect of oral consumption of honey-saffron syrup with date syrup on labor pain in nulliparous women (Persian)]. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2022;25(2):67–78. https://doi.org/10.22038/ijogi.2022.20328.

Sohrabi H, Shamsalizadeh N, Moradpoor F, Shahoei R. Comparison of the effects of date syrup with saffron-honey syrup on the progress of labor in nulliparous women: a single blind randomized clinical trial. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2022;27(4):301–7. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijnmr.ijnmr_282_21.

Hipni R, Megawati M, Tahiru Y, Hapisah H. [The effect of giving dates (Phoenix dactylifera) juice on delivery in the duration of 2nd stage of labor at PMB City Banjarmasin (Indonesian)]. Jurnal_Kebidanan. 2022;12(2):10–6. https://doi.org/10.33486/jurnal_kebidanan.v12i2.191.

Megawati M, Hipni R, Tahiru Y, Hapisah H. [The effectiveness of giving date juice on the long time of delivery at PMB City Banjarmasin in 2021 (Indonesian)]. Jurnal_Kebidanan. 2022;12(1):702–9. https://doi.org/10.33486/jurnal_kebidanan.v12i1.174.

Fathi L, Amraei K. [Effects of Phoenix dactylifera syrup consumption on the severity of labor pain and length of the active phase of labor in nulliparous women (Persian)]. Iran J Nurs. 2019;31(116):18–27. https://doi.org/10.29252/ijn.31.116.18.

Fathi L, Amraei K, Yari F. The effect of date consumption on the progress of labor in nulliparous women (Persian). J Islam Iran Tradit Med. 2018;9(3):219–26.

Taavoni S, Fathi L, Nazem Ekbatani N, Haghani H. The effect of oral date syrup on severity of labor pain in nulliparous. Shiraz E-Med J. 2019;20(1):e69207. https://doi.org/10.5812/semj.69207.

Kariman N, Yousefy Jadidi M, Jam Bar Sang S, Rahbar N, Afrakhteh M, Lary H. [The effect of consumption date fruit on cervical ripening and delivery outcomes (Persian)]. Pajoohande. 2015;20(2):72–7.

Yousefy Jadidi M, Jam Bar Sang SJB, Lari H. [The effect of date fruit consumption on spontaneous labor (Persian)]. J Pizhūhish dar dīn va salāmat (Research Relig Health). 2015;1(3):4–10.

Choirunissa R, Widowati R, Putri AE. The effect of dates consumption on increased hemoglobin levels in third trimester pregnant women at BPM “E”, Serang. STRADA Jurnal Ilmiah Kesehatan. 2021;10(1):938–42. https://doi.org/10.30994/sjik.v10i1.739.

Dahlan FM, Ardhi Q. The effect of Fe tablet and date palm on improving hemoglobin level among pregnant women in the third semester. J Midwifery. 2021;5(2):32–8. https://doi.org/10.25077/jom.5.2.32-38.2020.

Fauziah NA, Maulany N. [Consumption of dates to increase hemoglobin levels in third trimester pregnant women with anemia (Indonesian)]. Majalah Kesehatan Indonesia. 2021;2(2):49–54. https://doi.org/10.47679/makein.202136.

Manan A, Dinengsih S, Siauta JA. The effect of date fruit consumption on hemoglobin levels in pregnant women in trimester III. Jurnal Midpro. 2021;13(1):78–84. https://doi.org/10.30736/md.v13i1.253.

Murtiyarini I, Wuryandari AG, Suryanti Y. Effect of ferrous fumarate supplementation and date (Phoenix dactylifera) consumption on hemoglobin level of women in the third-trimester of pregnancy. J Res Dev Nurs Midw. 2021;18(2):5–7. https://doi.org/10.29252/jgbfnm.18.2.5.

Ma’mum NF, Kridawati A, Ulfa L. [Effect of adding dates extract on hemoglobin levels of anemia pregnant women at Fistha Nanda Clinic in 2020 (Indonesian)]. Jurnal Untuk Masyarakat Sehat (JUKMAS). 2020;4(2):201–15. https://doi.org/10.52643/jukmas.v4i2.1027.

Yuviska IA, Yuliasari D. [The effect of giving dates on increased hemoglobin levels in pregnant women with anemia at Rajabasa Indah Health Center Bandar Lampung (Indonesian)]. Jurnal Kebidanan Malahayati. 2020;5(4):343–8. https://doi.org/10.33024/jkm.v5i4.1860.

Wahyuni R, Sinaga EG, Agustinigsih D. [The effectiveness of giving dates on the effectiveness of the first day of post-partum breast milk expenditure (Indonesian)]. Avicenna. 2023;6(1):71–80. https://doi.org/10.36419/avicenna.v6i1.825.

Hiba N, Nisar S, Mirza ZA, Nisar S. Effect of date fruit consumption in later pregnancy on length of gestation, labour and delivery of nulliparous women. Pak Armed Forces Med J. 2022;72(6):2082–6. https://doi.org/10.51253/pafmj.v72i6.8122.

Iqbal S, Aftab S, Tehseen S, Mustafa R. Comparison of fetomaternal outcome with/without use of dates in primigravidae at term. Pak J Med Health Sci. 2022;16(10):40. https://doi.org/10.53350/pjmhs22161040.