Abstract

Background

Despite research suggesting an association between certain herb use during pregnancy and delivery and postnatal complications, herbs are still commonly used among pregnant women in sub-Sahara Africa (SSA). This study examines the factors and characteristics of women using local herbs during pregnancy and/or labor, and the associations between local herb use and postnatal complications in Kigoma, Tanzania.

Methods

We analyzed data from the 2016 Kigoma Tanzania Reproductive Health Survey (RHS), a regionally representative, population-based survey of reproductive age women (15–49 years). We included information on each woman’s most recent pregnancy resulting in a live birth during January 2014–September 2016. We calculated weighted prevalence estimates and used multivariable logistic regression to calculate adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for factors associated with use of local herbs during pregnancy and/or labor, as well as factors associated with postnatal complications.

Results

Of 3530 women, 10.9% (CI: 9.0–13.1) used local herbs during their last pregnancy and/or labor resulting in live birth. The most common reasons for taking local herbs included stomach pain (42.9%) and for the health of the child (25.5%). Adjusted odds of local herb use was higher for women reporting a home versus facility-based delivery (aOR: 1.6, CI: 1.1–2.2), having one versus three or more prior live births (aOR: 1.8, CI: 1.4–2.4), and having a household income in the lowest versus the highest wealth tercile (aOR: 1.4, CI: 1.1–1.9). Adjusted odds of postnatal complications were higher among women who used local herbs versus those who did not (aOR: 1.5, CI: 1.2–1.9), had four or more antenatal care visits versus fewer (aOR: 1.4, CI: 1.2–1.2), and were aged 25–34 (aOR: 1.1, CI: 1.0–1.3) and 35–49 (aOR: 1.3, CI: 1.0–1.6) versus < 25 years.

Conclusions

About one in ten women in Kigoma used local herbs during their most recent pregnancy and/or labor and had a high risk of postnatal complications. Health providers may consider screening pregnant women for herb use during antenatal and delivery care as well as provide information about any known risks of complications from herb use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that traditional and complementary medicine, accounts for 80% of health-care in the world [1]. Despite its frequency, there is a lack of standards ensuring the safe use of herbs for health purposes and literature linking herb use to various forms of adverse health events [2, 3] such as higher rates of pregnancy losses, increased use of caesarean section, increased frequency of maternal complications after delivery [4,5,6], increased occurrence of congenital malformations [7], congestive heart failure in newborns [8], and perinatal deaths [9].

In Tanzania, between 60 and 70% of the population seeks health care through the use of traditional medicine [10, 11], and tends to rely on traditional medicinal products to treat a wide-range of health conditions [12] including management of HIV/AIDS [13, 14], malaria [15], hypertension [16], sexually transmitted infections [17], and infant and child illnesses [18]. Studies on the estimated prevalence of local herbal use during pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) range between 40 and 90% [19, 20], but the prevalence of local herb use in Tanzania remains largely unknown. However, it is widely understood that traditional medicine, which is commonly comprised of herbal products, is popular in Tanzania due to the accessibility, availability, and low cost of herbal products compared with modern health care services across this region [21]. Use of local herbs during pregnancy may be particularly high as traditional healers and birth attendants remain key players in the delivery of care and are known to integrate traditional medicine into their practices [22]. Healthcare providers in SSA also continue to recommend local herbal products for treating a myriad of health issues during pregnancy [23,24,25], despite insufficient data to inform the safe use of herbal products during pregnancy [26, 27].

Previous global health studies have identified a number of maternal characteristics associated with herb use including maternal age [28, 29], marital status [28,29,30,31], education level [32, 33], birth order [29, 34], antenatal care [35,36,37,38], socioeconomic status [28, 32, 36], and rural residence [39,40,41].

Most of the current literature on the use of herbs in Tanzania has focused on conducting pharmacological studies on medicinal plants found in the region [14,15,16,17,18]. To date, no studies in this setting have examined local herb use (LHU) among pregnant women in relation to both maternal characteristics and pregnancy outcomes. Our study examines LHU in a representative sample of women with recent births in Kigoma Region, including the patterns of LHU, socio-demographic characteristics, and factors associated with LHU during pregnancy and/or labor. In a separate analysis, we explore the association of LHU during pregnancy and/or labor and early postnatal obstetric complications.

Methods

Study setting and design

Kigoma Region, located in the northwest corner of Tanzania by Lake Tanganika, covers 45,066 km2 and had a population of 2,127,930 in 2012. Approximately 83% of the population is classified as rural with farming as the primary economic activity [42]. In 2015, emergency obstetric and neonatal care facilities provided care for 83% of all direct obstetric complications. Eight out of ten maternal deaths in facilities were due to direct obstetric causes in 2011–2015 [43].

A regionally representative multistage survey of reproductive age women (15–49 years) was conducted in July–September 2016 in Kigoma, as part of a larger evaluation effort of the Project to Reduce Maternal Deaths in Tanzania. The project is a collaboration between Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Tanzania Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, the Elderly and Children (MoHCDGEC), Thamini Uhai, Vital Strategies and EngenderHealth, with financial support from Bloomberg Philanthropies and the H&B Agerup Foundation.

The survey was approved by the CDC Institutional Review Board and the Tanzania National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR) as the main evaluation approach to assess the maternal, child and reproductive health status, health service utilization and behaviors of women ages 15–49 in Kigoma region. Informed consent was obtained from household respondents at the beginning of the household interviews, and separately from eligible respondents at the start of the individual interviews. The consent was given verbally and attested on the paper questionnaire by the interviewer’s signature, date and time of giving consent, which were shown to the respondent, in accordance with the Tanzania NIMR requirements for human subject participation in population surveys. No compensation of any kind was provided to respondents who agreed to voluntarily participate in the survey. A detailed description of the survey methods and procedures are available elsewhere [44].

The survey included a regionally representative probability sample of women ages 15–49 that was selected using the 2012 National Census as the sampling frame. Maps and household listings for each enumeration area were updated during the month prior to the data collection. Trained interviewers obtained informed consent prior to conducting household and individual interviews. If obtained, interviewers then conducted confidential, face-to-face interviews using standardized questionnaires to collect information on households and individual women. The individual questionnaire asked information about a woman’s background characteristics, contraceptive behaviors and use, fertility, and detailed information about the most recent births (i.e., births during January 2014–September 2016) (see Additional file 1).

For the 2016 Kigoma Reproductive Health Survey (RHS), a total of 6461 of 6630 sampled households (97.5%) completed an interview. Within the responding households, 7023 of 7506 women aged 15–49 years (93.6%) responded. Of these women, 3531 (50.1%) women reported at least one live birth between January 2014 and September 2016 and were included in the analysis.

This study derived its main findings from the birth histories, which contained detailed information on birth outcomes (live birth or stillbirth), antenatal care, place and type of delivery and health behaviors during and after pregnancy, including LHU.

Inclusion criteria

For our analyses, we included information on LHU during the last pregnancy and/or labor resulting in live birth for all women who had a live born infant between January 2014 and September 2016. Details on the inclusion criteria and methodology of the survey in general are included in the 2016 Kigoma Region RHS Final Report [44].

Assessment of sociodemographic indicators

The sociodemographic indicators of interests included these selected variables: 1) Age (under 25, 25 to 34, 35 to 49); 2) Marital status (currently in a union, previously in a union, never in a union); 3) Residence (urban, rural); 4) Highest education completed (none, some primary, completed primary and/or higher); and 5) Household wealth index based on household assets (low, middle, high).

Characteristics of pregnancy and delivery

The characteristics of pregnancy and delivery among women reporting LHU were captured through the following variables: 1) LHU during their pregnancy and/or labor (yes/no); 2) Reasons for taking herbs (Induce or sustain labor, treat malaria, treat cold/flu, treat headache, treat convulsions, treat vaginal bleeding, treat stomach pain, for the health of the child, to avoid miscarriage, other (specify)); 3) When LHU was initiated and stopped (1st trimester, 2nd trimester, 3rd trimester, just before delivery, during/after delivery, does not remember); 4) Birth order (continuous); 5) Recommended antenatal care (ANC) received (yes/no). ANC responses were recoded as a dichotomous variable where women either met or did not meet the Tanzanian national guidance recommendation of four or more ANC visits during pregnancy [45]; 5) Gestational age at delivery (continuous); 6) Place of delivery (hospital/health center/dispensary, home, unknown); and 7) Postnatal complications (yes/no): Included only pregnancy obstetric complications with onset during the first 6 weeks of the postnatal period. Postnatal complications included severe bleeding; vaginal discharge, surgical infection, fainting, coma, high fever, pelvic pain, urinary incontinence, and bowel incontinence. Two obstetrician/gynecologist (Ob/Gyn) epidemiologists reviewed the survey responses to include only obstetric complications in the final analysis.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics

We calculated prevalence estimates with 95% confidence intervals for the following selected characteristics: overall LHU, reasons for LHU, LHU by demographic factors and clinically-relevant postnatal obstetric complications by LHU. We also examined the average number of days local herbs were used during pregnancy and/or labor and the proportion of herb users receiving recommended ANC.

Chi-squared statistics

We used chi-squared statistics to assess whether LHU during pregnancy and/or labor varied by residence, age, education level, marital status, wealth, parity, recommended ANC visits, and place of delivery. Also, chi-square tests were performed on whether postnatal obstetric complications varied with LHU during pregnancy and/or labor and by residence, age, education level, marital status, wealth, parity, recommended ANC visits, and place of delivery.

Multivariable models

We constructed two multivariable logistic regression models. The first model examined factors associated with LHU. The second model examined the association between LHU during pregnancy/labor and postnatal obstetric complications, while adjusting for any potential confounders. For both models, only the significant associations (p < 0.05) in the bivariate analyses were included in the full model, which were then removed sequentially based on a threshold of a p < 0.05. For the final multivariable model, we included age in our final model a priori because it is a well-documented risk factor for postnatal complications [46]. The results are presented as adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). We performed all analyses using SAS® software, Version 9.4 for Windows, using complex survey procedures to account for survey clustering and unequal sampling weights [47].

Results

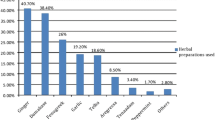

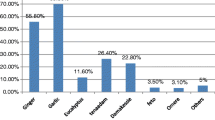

For their most recent pregnancy since January 2014 resulting in a live birth, 10.9% (95% CI: 9.0–13.1) of women reported use of herbs during pregnancy and/or labor. Of the 382 women who used herbs during pregnancy and/or labor, the most common reasons reported included stomach pain (42.9%), fetal health (25.5%), miscarriage avoidance (21.6%), and inducing or sustaining labor (12.2%). Among these same women, 17.8% used herbs for no more than 1 day, 41.1% 1–2 weeks, 14.1% between 1 to 2 months, and 21.2% between 3 to 9 months.

Bivariate analyses indicated that use of herbs during pregnancy and/or labor varied by a number of characteristics, including age group (p = 0.003), wealth tercile (p < 0.001), parity (p < 0.001), and place of delivery (p < 0.001). Herb use during pregnancy and/or labor did not differ significantly across groups by residence, education level, receipt of ANC, and marital status (Table 1).

Table 2 summarizes the full and reduced multivariable models for the association of selected characteristics with LHU during pregnancy and/or labor. The final reduced model indicated the odds of LHU during pregnancy and/or labor were higher for women reporting home versus facility-based delivery (aOR: 1.6, 95% CI: 1.1–2.2), having one versus multiple prior live births (aOR: 1.8, 95% CI: 1.4–2.4), and belonging to the lowest as compared to the highest household wealth tercile (aOR: 1.4, 95% CI: 1.0–1.9).

In the bivariate analyses, having a postnatal obstetric complication varied by whether or not a woman reported LHU during pregnancy and/or labor (p = 0.001), as well as by whether she reported receiving the recommended number of ANC visits (p < 0.001) (Table 3). We found no significant difference in the experience of postnatal obstetric complications by residence, birth order, delivery location, wealth tercile, age group, or educational level (Table 3). Additionally, LHU was higher among women who reported postnatal abnormal vaginal discharge (22.6%; 95% CI: 16.5–30.2; p = < 0. 001), high fever (16.1%; 95% CI: 12.6–20.3; p = < 0. 001), and pelvic pain (14.5%; 95% CI: 11.9–17.6; p = < 0.001) compared with those that did not use LHU during pregnancy and/or labor (Fig. 1).

In multivariable models the odds of having a postnatal complication was higher among women who reported LHU during pregnancy and/or labor versus those who did not (aOR: 1.5, 95% CI: 1.2–1.9), who had four or more ANC visits during pregnancy compared to those who did not (aOR: 1.4, 95% CI: 1.2–1.6) and were between the ages of 25–34 (aOR: 1.1, 95% CI: 1.0–1.3) or 35–49 (aOR: 1.3, 95% CI: 1.0–1.6) compared with the youngest age group < 25 (Table 4).

Discussion

This study examined the prevalence and characteristics of women with recent lives births who used local herbs during pregnancy and/or labor in Kigoma, Tanzania, as well as tested for associations between LHU during pregnancy and/or labor and postnatal obstetric complications.

Our study found lower reports of local herb use during pregnancy and/or labor among pregnant sub-Saharan African women than previously reported in the literature. Estimates from other studies have found the prevalence of traditional medicine in maternity care among African women to be as high as 80% [48]. One available study on the use of herbal products among pregnant women attending antenatal clinics in a rural district of Tanzania found a prevalence rate of 40.2% [20]. Studies conducted in clinical settings are not representative and may include more women who are seeking care because they are experiencing obstetric-related complications. Our study may undercount LHU during pregnancy due to the potential for recall and social desirability bias. However, this is the first study in SSA that documents LHU in a large and representative sample of women with recent births.

Consistent with other studies, LHU during pregnancy and/or delivery was higher among women with no prior births. These studies have shown that being a primigravida is associated with herbal use during pregnancy [20, 29, 34]. Primigravidas may lack information on the potential risks of herbal use in pregnancy. Communicating the health consequences of herbs used during pregnancy is limited due to the lack of empirical evidence needed to inform underlying health messages. These women may be prone to listen to family and/or friends that recommend herbal medicines during pregnancy, especially in regions where there are limited medical options for health care during pregnancy [29]. Furthermore, it is possible that the accessibility and availability may impact use of herbal products in resource-limited settings, particularly for home deliveries.

We found that the odds of using local herbs were the highest among women who belonged to the lowest household wealth group and had a home delivery; however, we also found a lack of association between LHU and several key sociodemographic factors. We did not find women’s educational level to be associated with LHU as was reported in a number of previous studies [49,50,51,52,53]. Similarly, we did not find factors associated with patterns of herb use during pregnancy related to marital status, or the gestational age of index pregnancy [34, 48, 54].

An association between LHU and postnatal obstetric complications at the population level in a representative sample of pregnant women was not previously documented in Tanzania. In our multivariable model, we found that postnatal obstetric complications were higher among women who were older than the age of 25, took herbs during pregnancy and/or labor, and completed four or more ANC visits during pregnancy. Women that experience pregnancy complications may consult in greater frequency alternative medicine practitioners during pregnancy [55]. More frequent ANC use may be associated with pregnancy complications that continue to manifest in postnatal period. Our study, however, cannot address a temporal association between the onset of and quantity ANC, complications, and herb use during pregnancy due to its cross-sectional design.

There are several key methodological limitations when considering these findings. First, elucidating patterns in deleterious health-related behaviors is often complex and may require special studies to explore contextual factors, such as the role of culture and tradition [56,57,58,59,60] and the interplay between individual, household and community characteristics. Though we recognize these factors are important, the study was not designed to explore these factors. Second, survey respondents were asked to provide information about past events and experiences going as far back as two years and nine months prior to the time of interview and thus, their reports may be subject to recall bias due to varying recall lengths. Steps were taken to improve data quality and mitigate measurement errors, including training interviewers to allow participants sufficient time for adequate recall of long-term memory, to ask prompting questions in relation to local or seasonal events, and to encourage responses in the local language to reduce poor understanding and communication between the interviewer and respondent. Also, women who experienced complications may be more likely to recall and report substances used during pregnancy. Third, social desirability bias or the tendency of respondents to provide answers they believe are more socially acceptable than responses that reflect their true behaviors may have also introduced measurement errors when participants were asked about their history of LHU during pregnancy [61]. Fourth, uterotonic potency has been shown by studies to vary depending on the plant-type as well as the preparation of herbs, quantity consumed, and frequency of intake [62–64]. Our study did not collect these details of use and we cannot explore further an association between LHU and experience of postnatal complications. How varying types, dosage, frequency and combination of herbs, affect pregnancy, delivery or postnatal complications remains unknown. Lastly, the survey did not collect data on patterns of LHU among women who did not carry the pregnancy out to term; due to this limitation in our data, we were not able to examine the associations between herb use during pregnancy and other pregnancy outcomes. Future studies may also consider examining associations between LHU and other markers of postnatal complications such as postnatal hospital re-admissions, blood transfusions, and antibiotic treatments, as well as more detailed accounts about puerperium and postnatal problems.

Conclusion

Traditional medicine continues to play a significant role in maternal behaviors and experiences across SSA, including Tanzania. In Kigoma Region, approximately one in ten women used local herbs during their last pregnancy and/or labor and the use was associated with having postnatal obstetric complications. While all women need accurate information on the potential risk of herb use during pregnancy and/or labor that is communicated clearly and culturally accessible, tailored messaging may be needed among women more likely to use herbs during pregnancy surrounding the varying degrees of risk depending on the type of herb, how it is prepared and consumed, as well as the frequency of intake. Understanding why women rely on LHU in relation with their characteristics may help identify challenges and barriers surrounding the utilization of maternal health services. Further assessment of specific local herbs used, period and dosage taken, and the properties of the herbs is still needed to clarify the pharmacological safety and efficacy of the specific local herbs used by pregnant women in Kigoma Region.

Availability of data and materials

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. All data that support the findings of this study are archived in the libraries of the CDC country office. While the data were not approved to be made publicly available by NIMR, there are standard procedures in place for other researchers to request the data that could be used with the permission of the Government of Tanzania. Requests for permission to access data can be submitted to NIMR to ensure these data are appropriate for the use sought, will be used consistent with any applicable legal restrictions on the data, and will be used for an appropriate purpose.

Abbreviations

- ANC:

-

Antenatal care

- aOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratios

- CDC:

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- HIV/AIDS:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus infection/acquired immune deficiency syndrome

- LHU:

-

Local herb use

- MoHCDGEC:

-

Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, the Elderly and Children, formerly known as Ministry of Health and Welfare

- NIMR:

-

National Institute for Medical Research

- Ob/Gyn:

-

Obstetrician/Gynecologist

- RCH:

-

Reproductive and Child Health

- RHS:

-

Reproductive Health Survey

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

World Health Organization. WHO: traditional medicine strategy 2014–2023. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

World Health Organization. WHO: guidelines for assessing quality of herbal medicines with references to contaminants and residues. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007.

Johns T, Sibeko L. Pregnancy outcomes in women using herbal therapies. Birth Defects Res B. 2003. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdrb.10052.

Borins M. The dangers of using herbs: what your patients need to know. Postgrad Med. 1998. https://doi.org/10.3810/pgm.1998.07.535.

Dugoua JJ, Mills E, Perri D, Koren G. Safety and efficacy of ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba) during pregnancy and lactation. Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;13:e277–84.

Rasch V, Kipingili R. Unsafe abortion in urban and rural Tanzania: method, provider and consequences. Tropical Med Int Health. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02327.x.

Chuang CH, Doyle P, Wang JD, Chang PJ, Lai JN, Chen PC. Herbal medicines used during the first trimester and major congenital malformations. Drug Saf. 2006. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200629060-00006.

Jones TK, Lawson BM. Profound neonatal congestive heart failure caused by maternal consumption of blue cohosh herbal medication. J Pediatr. 1998. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3476(98)70041-1.

Rahman AA, Ahmad Z, Naing L, Sulaiman SA, Hamid AM, Daud WNW. The use of herbal medicines during pregnancy and perinatal mortality in Tumpat District, Kelantan, Malaysia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2007;38:1150–7.

United Republic of Tanzania. The national traditional and traditional birth attendants Implementation Policy Guidelines. Tanzania, Dar-es-Salaam: Ministry of Health; 2000.

World Health Organization. General guidelines for methodologies on research and evaluation of traditional medicine. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000.

Mahonge CPI, Nsenga JV, Mtengeti EJ, Mattee AZ. Utilization of medicinal plants by Waluguru people in east Ulunguru mountains Tanzania. Afr J Tradit Complementary Altern Med. 2006;3:121–34.

Kayombo EJ, Uiso FC, Mbwambo ZH, Mahunnah RL, Moshi MJ, Mgonda YH. Experience of initiating collaboration of traditional healers in managing HIV and AIDS in Tanzania. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-3-6.

Kisangau DP, Lyaruu HVM, Hosea KM, Joseph CC. Use of traditional medicines in the management of HIV/AIDS opportunistic infections in Tanzania: a case in the Bukoba rural district. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-3-29.

Gessler MC, Msuya DE, Nkunya MH, Mwasumbi LB, Schär A, Heinrich M, et al. Traditional healers in Tanzania: the treatment of malaria with plant remedies. J Ethnopharmacol. 1995. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-8741(95)01293-M.

Liwa A, Roediger R, Jaka H, Bougaila A, Smart L, Langwick S, Peck R. Herbal and alternative medicine use in Tanzanian adults admitted with hypertension-related diseases: a mixed-methods study. Int J Hypertens. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/5692572.

Maregesi SM, Ngassapa OD, Pieters L, Vlietinck AJ. Ethnopharmacological survey of the Bunda district, Tanzania: plants used to treat infectious diseases. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2007.07.006.

Kayombo, EJ. Traditional methods of protecting the infant and child illness/disease among the Wazigua at Mvomero Ward, Morogoro, Region, Tanzania. Altern Integ Med. 2013; doi: https://doi.org/10.4172/2327-5162.1000103.

Liwa AC, Smart LR, Frumkin A, Epstein HAB, Fitzgerald DW, Peck RN. Traditional herbal medicine use among hypertensive patients in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-014-0437-9.

Mbura Q, et al. The use of oral herbal medicine by women attending antenatal clinics in urban and rural Tanga district in Tanzania. East Afr Med J. 1985;62:540–50.

Kitula RA. Use of medicinal plants for human health in Udzungwa Mountains forests: a case study of new Dabaga Ulongambi Forest reserve. Tanzania J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-3-7.

Kayombo EJ. Traditional birth attendants (TBAs) and maternal health Care in Tanzania. In: Kalipen E, Thiuri P, editors. Issues and perspectives on health Care in Contemporary sub - Saharan Africa by studies in Africa health and medicine. Queenston: Lampeter; 1997. p. 288–305.

Marcus DM, Snodgrass WR. Do no harm: avoidance of herbal medicines during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2005. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000158858.79134.ea.

Hepner DL, Harnett M, Segal S, Camann W, Bader A, Tsen L. Herbal use in parturients. Anesth Analg. 2002. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000539-200203000-00039.

Tsui B, Dennehy CE, Tsourounis C. A survey of dietary supplement use during pregnancy at an academic medical center. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001. https://doi.org/10.1067/mob.2001.116688.

Ernst E. Herbal medicinal products during pregnancy: are they safe? 2003. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.t01-1-01009.x.

Cuzzolin L., Benoni G. Safety issues of Phytomedicines in pregnancy and Paediatrics. In: Ramawat K., editors. Herbal drugs: Ethnomedicine to modern medicine. Heidelberg: Springer, 2009. P381–396.

Nordeng CB, Uwakwe KA, Chinomnso NC, Mbachi II, Diwe KC, Agunwa CC, et al. Socio-demographic Determinants of Herbal Medicine Use in Pregnancy Among Nigerian Women Attending Clinics in a Tertiary Hospital in Imo State, South-East, Nigeria. Am J Med Sci. 2016. https://doi.org/10.12691/ajms-4-1-1.

Nordeng H, Haven GC. Impact of socio-demographic factors, knowledge and altitude on the use of herbal drugs in pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2005. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0001-6349.2005.00648.x.

Holst L, Wright D, Haavik S, Nordeng H. The use of the user of herbal remedies during pregnancy. J Altern Complement Med. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2008.0467.

Broussard CS, Louik C, Honein MA, Mitchel AA, and the National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Herbal use before and during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009; doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2009.10.865.

Orief YI, Farghaly NF, Ibrahim MIA. Use of herbal medicines among pregnant women attending family health centers in Alexandria. Middle East Fertil Soc. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mefs.2012.02.007.

Fakeye TO, Adisa R, Musa IE. Attitude and use of herbal medicines among pregnant women in Nigeria. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-9-53.

Nordeng H, Harven G. Use of herbal drugs in pregnancy: a survey among 400 Norwegian women. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2004. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.945.

Gharoro EP, Igbafe AA. Pattern of drug use amongst antenatal patients in Benin City. Nigeria Med Sci Monit. 2000;6:CR84–7.

Duru CB, Uwakwe KA, Chinomnso NC, Mbachi II, Diwe KC, Agunwa CC, et al. Socio-demographic Determinants of Herbal Medicine Use in Pregnancy Among Nigerian Women Attending Clinics in a Tertiary Hospital in Imo State, South-East, Nigeria. Am J Med Sci. 2016. https://doi.org/10.12691/ajms-4-1-1.

Ndyomugyenyi R, Neema S, Magnussen P. The use of formal and informal services for antenatal care and malaria treatment in rural Uganda. Health Policy Plan. 1998. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/13.1.94.

Ajaari J, Masanja H, Weiner R, Abokyi SA, Owusu-Agyei S. Impact of place of delivery on neonatal mortality in rural Tanzania. Int J MCH AIDS. 2012;1:49–59.

Adams J, Sibbritt D, Lui CW. The urban-rural divide in complementary and alternative medicine use: a longitudinal study of 10,638 women. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-11-2.

Robinson A, Chesters J. Rural diversity in CAM usage: the relationship between rural diversity and the use of complementary and alternative medicine modalities. Rural Soc. 2008. https://doi.org/10.5172/rsj.351.18.1.64.

Wilkinson JM, Simpson MD. High use of complementary therapies in a New South Wales rural community. Aust J Rural Health. 2001. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1038-5282.2001.00351.x.

National Bureau of Statistics & Office of Chief Government Statistician. 2012 Population and Housing Census: Population Distribution by Administrative Areas. Dar es Salaam and Zanzibar, Tanzania: NBS Office of Chief Government Statistician; 2013.

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reducing Maternal Mortality in Tanzania: Selected Pregnancy Outcomes Findings from Kigoma Region, Tanzania. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016.

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Kigoma reproductive health survey: Kigoma region, Tanzania. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016. p. 2017.

United Republic of Tanzania: Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children. The National Road Map Strategic Plan to Improve Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child & Adolescent Health in Tanzania (2016–2020): One Plan II. 2016; Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: Author.

Cavazos-Rehg PA, Krauss MJ, Spitznagel EL, Bommarito K, Madden T, Olsen MA, et al. Maternal age and risk of labor and delivery complications. Matern Child Health J. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995.

SAS Institute. SAS/ACCESS® 9.4 Interface to ADABAS: Reference. 2013. Cary. NC: SAS Institute Inc.

Shewamene Z, Dune T, Smith CA. The use of traditional medicine in maternity care among African women in Africa and the diaspora: a systematic review. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-017-1886-x.

Gibson PMS, Powrie R, Star J. Herbal and alternative medicine use during pregnancy: a cross-sectional survey. Obstet Gynecol. 2001. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0029-7844(01)01250-9.

Rashmi S, Bhuvneshvar K, Ujala V. Drug utilization pattern during pregnancy in North India. Indian J Med Sci. 2006;60:277–87.

Moussalhy K, Oraichi D, Berard A. Herbal products use pregnancy: prevalence and predictors. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.1731.

Foster DA, Denning A, Wills G, Bolger M, McCarthy E. Herbal medicine use during pregnancy in a group of Australian women. BMC Pregnancy Childb. 2006. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-6-21.

Henry A, Crowder C. Patterns of medication use during and prior to pregnancy: the MAP study. Aust Nz J Obstet Gyn. 2000. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1479-828X.2000.tb01140.x.

Usta IM, Nassar AH. Advanced maternal age Part I: obstetric complications Am J Perinatol. 2008. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0028-1085620.

Skouteris H, Wertheim EH, Rallis S, Paxton SJ, Kelly L, Milgrom J. Use of complementary and alternative medicines by a sample of Australian women during pregnancy. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1479-828X.2008.00865.x.

Szreter S, Woolcock M. Health by association? Social capital, social theory, and the political economy of public health. Int J Epidemiol. 2004. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyh013.

Navarro V, Muntaner C, Borrell C, Benach J, Quiroga Á, Rodríguez-Sanz M, et al. Politics and health outcomes. Lancet. 2006. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69341-0.

Flaskerud JH, Winslow BJ. Conceptualizing vulnerable populations health-related research. Nur Res. 1998;47:69–78.

Pachter LM. Culture and clinical care: folk illness beliefs and behaviors and their implications for health care delivery. JAMA. 1994;271:690–4.

Rogers SM, Miller HG, Turner CF. Effects of interview mode on bias in survey measurements of drug use: do respondent characteristics make a difference? Subst Use Misuse. 1998;33:2179–200.

Ssegawa P, Kasenene JM. Medicinal plant diversity and uses in the Sango bay area. Southern Uganda J Ethnopharmacol. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2007.07.014.

Steenkamp V. Traditional herbal remedies used by south African women for gynaecological complaints. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-8741(03)00053-9.

Tripathi V, Stanton C, Anderson FW. Traditional preparations used as uterotonics in sub-Saharan Africa and their pharmacologic effects. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.06.020.

Kreuter MW, McClure SM. The role of culture in health communication. Annu Rev Public Health. 2004. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123000.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to our donors (Bloomberg Philanthropies) and the CDC Foundation. Our special thanks to the local implementing agency, AMCA Inter-Consult Ltd., whose hard work and collaborations enabled the collection of these data. We are grateful to the Governments of Tanzania, the Regional and District Health Offices, the supervisors and interviewers, and the respondents in Kigoma region. Special thanks to Emily Petersen at CDC for providing technical expertise in the questionnaire design and formulating the interviewer-administered questions on local herb use during pregnancy and/or labor for the 2016 Kigoma RHS. We also thank Dr. Karen Pazol for providing valuable feedback and guidance during the CDC revision process and Janel Blancett, of the CDC Foundation for assisting with the literature review.

Funding

This study was funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies and the H&B Agerup Fondation through an agreement with CDC and CDC Foundation. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RF was responsible for data analysis, interpreting findings, and writing the manuscript. DM helped with interpreting the results and reviewing the manuscript. CB helped with data preparation and analysis, interpreting the results and reviewing the manuscript. AR was responsible for data preparation and reviewing the manuscript. GM helped with reviewing the manuscript. FS led the RHS study design, data collection, analysis and dissemination, and helped with writing and reviewing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript submitted for publication.

Authors’ information

Authors’ names and affiliations are already in the document.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Kigoma Reproductive Health Survey (RHS) is a part of a larger external evaluation of the Maternal and Reproductive Health in Tanzania project. The study protocol was approved by the Tanzania National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR), complied with Tanzania procedures for protecting human rights in research, and was deemed non-research by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Human Research Protection Office of the Center for Global Health.

Informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Tanzania NIMR procedures that allow for verbal consent due to high illiteracy rates. Prior to beginning asking questions in selected households, interviewers read to all household respondents a statement including the purpose of the study, why it is important to participate, how the interview will be conducted, interview duration, how the data will be protected, and how all answers are voluntary. The respondent verbal consent was recorded in the paper questionnaire by the interviewer, shown to the respondent and attested by signature of the interviewer, and date and time of the consent. The interviewer read to the household respondent the following statement:

“Hello. My name is _______________________________________. I am working with the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare. We are conducting a survey about health in Kigoma. The information we collect will help the government to plan health services. Your household was selected for the survey. The household survey usually takes about 10 minutes, and then we may do a longer interview of women in the household. All of the answers you give will be confidential and will not be shared with anyone other than members of our survey team. You don’t have to be in the survey, but we hope you will agree to answer the questions since your views are important. If I ask you any question you don’t want to answer, just let me know and I will go on to the next question or you can stop the interview at any time. Do you have any questions? (Y/N); May I begin the interview now? (Y/N, signature and date)”.

Similarly, a separate verbal consent was obtained from all women aged 15–49 in selected households. Only those who provided consent after they were made aware about the purpose and public health importance of the study, interview duration, confidentiality, voluntary participation and right to not answer any or all questions were interviewed. Each consent was recorded, shown to the respondent, and attested by the signature of the interviewer, including date and time of the consent. Prior to the beginning of the individual questionnaire, the interviewer read to each eligible woman the following introduction and consent statement:

“Hello. My name is ___________________. I am working with the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare. We are conducting a survey about health in Kigoma. The information we collect will help the government to plan health services. Your household was selected for the survey. The survey usually takes about 30 to 60 minutes. All of the answers you give will be confidential and will not be shared with anyone other than members of our survey team. You don’t have to be in the survey, but we hope you will agree to answer the questions since your views are important. If I ask you any question you don’t want to answer, just let me know and I will go on to the next question or you can stop the interview at any time. Do you have any questions? (Y, followed by answers/N); May I begin the interview now? (Y/N, signature and date)”.

Interviews of women aged 15–17 did not require parental consent. For this study, need for parental consent was waived by the Tanzanian National Institute of Medical Research (NIMR) during the ethical approval of the protocol NIMR/HQ/R.8a/Vol. IX/1696 on March 19th, 2014. Every care was taken to ensure the privacy and confidentiality of the interviews for all respondents and the study data.

Prior to visiting facilities, communities, and households, teams sought written approval from the Tanzania Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, the Elderly and Children (MoHCDGEC), Reproductive and Child Health section (MoHCDGEC/RCH) and regional and district authorities including ward and village leaders. Letters were sent from MoHCDGEC/RCH describing the activity and its approval.

All field personnel, including data collectors and field work staff signed a “confidentiality pledge”. This was intended as an extra measure to protect confidentiality and anonymity of the respondents. All data were stored on password protected hard drives, with access permitted to the research personnel only. Prior to analysis, the data processing specialists removed personally-identifiable information, such as the name of the parish and village and names of the household members on the household rosters. Raw data—paper forms and electronic copies of the original databases—were kept for three years following the study completion, after which they were destroyed.

Findings from this evaluation were used for subsequent program decision-making by the funding institution, Bloomberg Philanthropies. Reports and recommendations were shared with the MoHCDGEC and regional representatives, the funder, and the implementing partners.

Consent for publication

The ethics committees did not require the project to seek consent for publication from individual participants. Our study was based on anonymized data with no identifiable information on survey respondents. Written consent was obtained for each individual in each household, who provided their information voluntarily, was informed about confidentiality of the study, and approved the use of information for improving public health and clinical practices. The manuscript does not include details, images, or videos relating to individual participants.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

The 2016 Reproductive Health Survey Kigoma Region Individual Questionaire asked information about a woman's background characteristics, contraceptive behaviors and use, fertility, and detailed information about the most recent births.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Fukunaga, R., Morof, D., Blanton, C. et al. Factors associated with local herb use during pregnancy and labor among women in Kigoma region, Tanzania, 2014–2016. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 20, 122 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-2735-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-2735-3