Abstract

Background

During the COVID-19 pandemic, hospitals’ decision of not admitting pregnant women’s partner or support person, and pregnant women’s fear of contracting COVID-19 in hospitals may disrupt prenatal care. We aimed to examine whether prenatal care utilization in South Carolina varied before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, and whether the variation was different by race.

Methods

We utilized 2018–2021 statewide birth certificate data using a pre-post design, including all women who delivered a live birth in South Carolina. The Kotelchuck Index - incorporating the timing of prenatal care initiation and the frequency of gestational age-adjusted visits - was employed to categorize prenatal care into inadequate versus adequate care. Self-reported race includes White, Black, and other race groups. Multiple logistic regression models were used to calculate adjusted odds ratio of inadequate prenatal care and prenatal care initiation after first trimester by maternal race before and during the pandemic.

Results

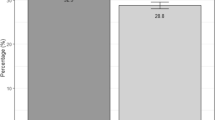

A total of 118,925 women became pregnant before the pandemic (before March 2020) and 29,237 women during the COVID-19 pandemic (March 2020 – June 2021). Regarding race, 65.2% were White women, 32.0% were Black women and 2.8% were of other races. Lack of adequate prenatal care was more prevalent during the pandemic compared to pre-pandemic (24.1% vs. 21.6%, p < 0.001), so was the percentage of initiating prenatal care after the first trimester (27.2% vs. 25.0%, p < 0.001). The interaction of race and pandemic period on prenatal care adequacy and initiation was significant. The odds of not receiving adequate prenatal care were higher during the pandemic compared to before for Black women (OR 1.26, 95% CI 1.20–1.33) and White women (OR 1.10, 95% CI 1.06–1.15). The odds of initiating prenatal care after the first trimester were higher during the pandemic for Black women (OR 1.18, 95% CI 1.13–1.24) and White women (OR 1.09, 95% CI 1.04–1.13).

Conclusions

Compared to pre-pandemic, the odds of not receiving adequate prenatal care in South Carolina was increased by 10% for White women and 26% for Black women during the pandemic, highlighting the needs to develop individual tailored interventions to reverse this trend.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

The United States (US) lags behind other high-income countries in terms of maternal mortality and infant mortality [1]. With 20.1 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 2019, the US ranks last among developed countries [1, 2]. With an infant mortality rate of 5.6 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2019, the US ranks 33rd out of 36 member countries of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) [1, 3]. Furthermore, racial and ethnic disparities exist in US maternal and infant mortality. Non-Hispanic Black women face 3.2 times higher maternal mortality rate than non-Hispanic White women [2, 4, 5]. Similarly, non-Hispanic Black children experience 2.3 times the infant mortality rate of non-Hispanic Whites [3].

In the joint guidelines for perinatal care, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Academy of Pediatrics emphasize the importance of adequate prenatal care to achieve optimal maternal and infant outcomes [6]. Prenatal care allows continuously identifying and assessing risks for mothers and offspring, as well as implementing and adapting appropriate care plans. Inadequate prenatal care increases the risk of preterm delivery, low birth weight, neonatal death, and infant death [7,8,9]. Having four prenatal visits or less, and initiating prenatal care after the first trimester are associated with excess maternal mortality [10]. Black women are less likely to have adequate prenatal care and initiate prenatal care during the first trimester compared to White women [10]. Moreover, Healthy People 2030 has adopted the objective to increase the proportion of pregnant women who receive early and adequate prenatal care to 80.5% [11]. In 2016, 77.1% of women giving birth in the US initiated prenatal care in the first trimester, and 75.6% of women giving birth received adequate prenatal care; in South Carolina, those percentages were respectively 72.0% and 76.0% [12].

During the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic, many US hospitals made decisions affecting prenatal care experiences. First, several in-person prenatal visits were replaced with virtual visits or phone calls [13,14,15]. Second, no partner, family member or support person was allowed to attend in-person prenatal visits with the pregnant women [13, 14, 16]. In reaction, pregnant women reported feeling a lack of social support during prenatal visits, including loss of companionship, loss of informational, emotional, and physical help due to the absence of their support persons [14,15,16,17,18]. Pregnant women also reported fear and anxiety about the risk of contracting COVID-19 in hospitals [14, 15, 17]. Worries about safety of in-person prenatal care and about having support persons during prenatal care and delivery were higher for racial and ethnic minorities compared to non-Hispanic White pregnant women [19,20,21,22]. In New York State, non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic women more frequently expressed having negative prenatal experiences than non-Hispanic White women during the COVID-19 pandemic [23].

Studies using small samples and/or online convenient samples appear to show a decrease in prenatal visits during the COVID-19 pandemic as a result of worries of pregnant women [15, 16, 18, 21]. Participants reported missing, cancelling, or delaying prenatal visits to decrease the risk of being exposed to COVID-19 [15, 18, 21]. There is a need for population-wide studies assessing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adequacy of prenatal care.

Based on South Carolina statewide birth certificates, this study sought to assess whether the prenatal care utilization varied before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, and whether the variation was moderated by race. We hypothesized that during the pandemic, women were less likely to get adequate prenatal care and initiate prenatal care early than before the pandemic. This study will provide empirical data on how the COVID-19 pandemic may have impacted access to prenatal care, which are much needed for the program development to improve prenatal care utilization during the pandemic and future pandemics.

Methods

Design and study population

All pregnant women giving birth in South Carolina from January 2018 to June 2021 were included from a statewide vital records birth certificate dataset. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of South Carolina and the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control, and followed procedures in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional review boards. Informed consent was waived because this study used de-identified data from a statewide vital records birth certificate dataset and had no more than the minimal risk.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of interest was the adequacy of prenatal care, which was based on the Kotelchuck Index also known as Adequacy of Prenatal Care Utilization (APNCU). The Kotelchuck Index incorporates the timing of prenatal care initiation and the number of prenatal visits adjusted for gestational age [24] and categorized prenatal care utilization into 4 levels, namely adequate plus, adequate, intermediate, and inadequate. When prenatal care begins by the fourth month of pregnancy, the index is adequate plus if the pregnant women receive ≥ 110% of recommended visits, adequate if she receives 80–109%, and intermediate if she receives 50–79%. If the prenatal care starts after the fourth month of pregnancy, or the pregnant women receives less than 50% of expected visits, the index is inadequate [24]. In this study, prenatal care was considered as adequate if the Kotelchuck Index category was adequate plus or adequate. The secondary outcome was early initiation of prenatal care defined by the prenatal care starting within the first three months of gestation.

Exposure and covariates

The exposure of interest was pandemic period, which was classified as pre-pandemic if the pregnancy started before March 2020, and pandemic if it started on March 2020 or after. Pregnancy starting time was estimated using the delivery date minus gestational age at the delivery.

Covariates that could potentially affect prenatal care utilization were chosen according to Andersen’s health care utilization model [25]: predisposing factors (race, age, education level), enabling factors (health insurance, participation in supplemental nutrition program as a proxy for income), and need factors (clinical variables of mother and child).

Maternal variables included sociodemographic variables namely race, age, education level, health insurance, participation in supplemental nutrition program. Self-reported race was classified as White, Black, and other. Age was classified as less than 20 years, 20 to 34 years, and 35 years or more, highlighting age groups more at risk of pregnancy complications [26, 27]. Education was categorized into less than high school graduate, high school graduate/associate degree, college graduate or above. Health insurance was classified as private health insurance, Medicaid, or none. Participation in supplemental nutrition program (WIC) was reported as yes or no. Maternal clinical variables such as previous live birth, previous cesarean delivery, diabetes (pre-pregnancy/gestational), hypertension (pre-pregnancy/gestational), and smoking during pregnancy were reported as yes or no. Pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) was categorized as underweight or normal weight (< 25.0), overweight (25.0–29.9) and obese (≥ 30.0). Child clinical variables included gestational age and plurality. Gestational age was categorized into preterm (< 37 weeks), and not preterm (≥ 37 weeks). Plurality was reported as single fetus and multiple fetuses.

Statistical analyses

Counts and percentages were calculated for categorical variables, mean and standard deviation were calculated for numeric variables. For bivariate analyses, Chi square tests were performed to assess the association between the pandemic or covariates and initiation or adequacy of prenatal care. Regarding multivariable analyses, first an unadjusted logistic regression model was performed to test the association between the pandemic and adequacy of prenatal care, and between the pandemic and early initiation of prenatal care. Second, the model was adjusted for the above-mentioned covariates. Finally, the pandemic*race was added to the adjusted model. A separate statistical model was computed for each stratum of race if the interaction term was significant. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. SAS 9.4 version (SAS institute, Cary, NC) was utilized for data cleaning and data analysis.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

There were 153,085 women giving birth from January 2018 to June 2021 in South Carolina (Fig. 1). A total of 4,923 observations were excluded due to missing values in adequacy of prenatal care (n = 194), race (n = 122), and covariates (n = 4,607); among covariates, WIC (n = 1,872) and BMI (n = 1,752) contributed most to missing. Those excluded were more likely to be on Medicaid, not participate in WIC, have lower levels of education, have lower pre-pregnancy BMI, delay prenatal care initiation, not receive adequate prenatal care than those remaining (Supplementary Table 1). The remaining 148,162 constituted the analytical sample. Regarding the period, 118,925 women became pregnant during the pre-pandemic period, and 29,237 during the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 1).

The racial composition of women who became pregnant during the pandemic (65.0% White women, 32.4% Black women) and before the pandemic (65.3% White women, 31.9% Black women) was similar (p = 0.03) (Table 1). A lower percentage of women participated in WIC during the pandemic compared to before (31.8% vs. 37.9, p < 0.001). During the COVID-19 pandemic a higher percentage of women had diabetes (9.3% vs. 8.1%, p < 0.001) and a higher proportion of births were preterm deliveries (13.0% vs. 10.2%, p < 0.001) compared to before the pandemic. Conversely, a lower percentage of women smoked during pregnancy in the pandemic period compared to before (6.0% vs. 7.6%, p < 0.001).

Pandemic period and inadequate prenatal care

Overall, 22.1% (32,715) of the women did not receive adequate prenatal care. The percentage of women not receiving adequate prenatal care was higher during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to before (24.1% vs. 21.6%, p < 0.001) (Table 2). The percentage of women not receiving adequate prenatal care was higher among Black women and other race compared to White (respectively 25.9%, 24.3%, and 20.1%, p < 0.001). The odds of lack of adequate prenatal care were higher during the pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic period (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 1.16, 95% CI 1.12–1.20) (Table 3). Interaction between pandemic and race was significant in both unadjusted and adjusted models (p < 0.001). The odds ratio of pandemic vs. pre-pandemic lack of adequate prenatal care was significant for Black women (AOR 1.26, 95% CI 1.20–1.33) and for White women (AOR 1.10, 95% CI 1.06–1.15), yet not significant for other races.

Pandemic period and lack of prenatal care and delayed prenatal care initiation

During the pandemic, the percentage of women who did not have prenatal care increased to 3.7% from 1.5% during the pre-pandemic period (p < 0.001). Not having prenatal care varied by race/ethnicity: 1.6% of White women, 2.5% of Black women and 2.5% of other races (p < 0.001). The mean number of prenatal visits was 11.91 during the pandemic compared to 12.24 during the pre-pandemic period.

Overall, 25.4% of the women did not initiate their prenatal care by the third month of pregnancy. The percentage of women not initiating their prenatal care by the third month was higher during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to before (27.2% vs. 25.0%, p < 0.001) (Table 2). Similarly, the percentage of women not initiating their prenatal care by the third month was higher among Black women (30.0%) and other races (29.4%) compared to White women (23.1%), p < 0.001. The odds of delayed prenatal care initiation were higher during the pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic period (AOR 1.12, 95% CI 1.09–1.16) (Table 4). Interaction between pandemic and race was significant in both the unadjusted (p = 0.002) and adjusted (p = 0.02) models. The odds ratio of delayed prenatal care initiation comparing the pandemic to the pre-pandemic period was significant for Black women (AOR 1.18, 95% CI 1.13–1.24) and for White women (AOR 1.09, 95% CI 1.04–1.13), yet not significant for other races.

Discussion

This study shows that the percentage of pregnant women not receiving adequate prenatal care and not initiating prenatal care by the third month of pregnancy in South Carolina increased during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to before the pandemic. The odds of lack of adequate prenatal care and the odds of delayed prenatal care initiation were higher during the pandemic in the models after adjusting for predisposing, enabling and need factors. A difference of 2 − 3% in adequacy of prenatal care and in early prenatal care initiation may seem small, but it is a setback in improving prenatal care adequacy and reaching the Healthy People 2030 target in South Carolina [11]. Online surveys conducted on US women and US obstetric workforce also mentioned a decrease in number of prenatal visits during the COVID-19 pandemic [15, 16, 18, 21]. Knowing the existence of racial disparities in maternal and infant mortality [2,3,4,5], and considering that the lack of adequate prenatal care increases the risk of neonatal, infant and maternal death [7,8,9,10], racial disparities in access to prenatal care during the COVID-19 pandemic could potentially contribute to the widening of racial gaps.

This study also found that the pre-post variation in adequacy of prenatal care and early prenatal care initiation was moderated by race. For Black women and White women, the odds of lack of adequate prenatal care were higher during the pandemic compared to before. The odds of delayed prenatal care initiation also increased during the pandemic compared to before among Black women and White women. The pre-post increases in lack of adequate prenatal care utilization and delayed prenatal care initiation were more severe in Black women. Surveys and qualitative studies conducted in different US states found higher worries among racial minorities compared to White women regarding contracting COVID-19 during prenatal care and not having support persons [19,20,21,22]. In addition, Black women more frequently expressed having negative prenatal experiences than White women during the COVID-19 pandemic [23]. Black women also reported experiencing changes in health care related to discrimination and indicated that systemic racism in the healthcare system had worsened during the pandemic [19].

These findings suggest that racial and ethnic groups face different challenges and barriers to prenatal care utilization particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, policy efforts in maternity health improvements should address the prenatal care utilization by facilitating more patient-centered care to better reach a wide range of pregnant families during the difficult times of the COVID-19 pandemic [28, 29]. In addition, psychosocial support needs to be increased and varied in order to reduce barriers to prenatal care. Findings from this study confirming racial disparities in declining of prenatal care adequacy during the COVID-19 pandemic will help explain the likely mechanism for a possible widening of racial gaps in maternal and perinatal outcomes.

This study is not without limitations. Overall, 3.2% of the observations (2.8% of pandemic and 3.3% of pre-pandemic observations) were excluded because of missing values; and those excluded tend to have lower socioeconomic status and are less likely to receive adequate prenatal care than those included. Therefore, the estimates of inadequate prenatal care or no prenatal care might be underestimated. South Carolina has a small proportion of Hispanics; thus, our results may not be generalizable to Hispanics who are among the groups more affected by the COVID-19 pandemic [30]. There can be discrepancies between birth certificate information and medical records of pregnant women. Furthermore, the birth certificate dataset does not specify whether prenatal visits were in-person or remote, while during the pandemic many in-person visits were changed to remote [13,14,15]. Our data indicated the differences in participant characteristics such as pre-pregnancy BMI, previous live birth, participation in WIC, gestational age at birth, hypertension, and diabetes, and external factors other than the COVID-19 pandemic, which might also influence the changes in adequacy of prenatal care given the pre-post design. These observed differences were consistent with literature regarding an increase in average BMI and obesity prevalence among US adults during the pandemic [31], as well as an increase in challenges to participation in WIC program [32]. Women with COVID-19 are found to be at higher risk of preterm birth [33]. Nevertheless, our results were adjusted for predisposing (race, age, education level), enabling (health insurance, participation in WIC) and need factors (clinical variables of mother and child) that may affect prenatal care utilization; and the COVID-19 pandemic affected so many external factors (such as employment, childcare, transportation) that the latter are more likely to be mediators than confounders. While the Kotelchuck index measures the timing of prenatal care initiation and the number of prenatal visits, it does not measure the quality of prenatal visits. Despite the limitations, this study has multiple strengths: among them the use of state-wide data, the size of the study population, the use of several measures of prenatal care which assess the different domains (adequacy, timing of initiation, and number of visits) and the consistency of findings regardless of statistical tests, models, and component of prenatal care adequacy.

Conclusions

In conclusion, during the COVID-19 pandemic pregnant women had higher odds of not receiving adequate prenatal care, and higher odds of delayed prenatal care initiation compared to the pre-pandemic period. Black women were disproportionately affected compared to White women and other races. The decline of prenatal care adequacy and early prenatal care initiation during the COVID-19 pandemic represents a setback in reaching the Healthy People 2030 targets in South Carolina, more severely among Black women. Appropriate and tailored interventions including awareness on prenatal care adequacy, increase in psychosocial support, and changes in prenatal care delivery should be implemented to reverse this trend.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the South Carolina (SC) Department of Health and Environmental Control (DHEC) and the SC Office of Revenue and Fiscal Affairs, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the South Carolina (SC) Department of Health and Environmental Control (DHEC) and the SC Office of Revenue and Fiscal Affairs. Requests should be directed to the corresponding author Jihong Liu.

Abbreviations

- APNCU:

-

Adequacy of Prenatal Care Utilization

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- OECD:

-

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

- OR:

-

Odds Ratio

- RR:

-

Rate Ratio

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- US:

-

United States

- WIC:

-

Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children

References

America’s Health Rankings. International Comparison | 2019 Annual Report. 2021. Available from: https://www.americashealthrankings.org/learn/reports/2019-annual-report/international-comparison [cited 2022 Feb 20]

Hoyert DL. Maternal Mortality Rates in the United States, 2019. NCHS Health E-Stats. 2021. https://doi.org/10.15620/cdc:103855 [cited 2022 Feb 4]

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reproductive Health | Maternal and Infant Health. 2021. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/infantmortality.htm [cited 2022 Feb 20]

Collier ARY, Molina RL. Maternal Mortality in the United States: Updates on Trends, Causes, and Solutions. Neoreviews. 2019;20(10):e561. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7377107/ [cited 2022 Feb 4]

Petersen EE, Davis NL, Goodman D, Cox S, Syverson C, Seed K et al. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Pregnancy-Related Deaths — United States, 2007–2016. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(35):762–5. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/wr/mm6835a3.htm [cited 2022 Feb 4]

AAP Committee on Fetus and Newborn, ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice. Guidelines for Perinatal Care. Eight Edit. 2017. 691 p.

Partridge S, Balayla J, Holcroft CA, Abenhaim HA. Inadequate prenatal care utilization and risks of infant mortality and poor birth outcome: a retrospective analysis of 28,729,765 U.S. deliveries over 8 years. Am J Perinatol. 2012;29(10):787–93. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22836820/ [cited 2022 Feb 20]

Holcomb DS, Pengetnze Y, Steele A, Karam A, Spong C, Nelson DB. Geographic barriers to prenatal care access and their consequences. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2021;3(5). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34245930/ [cited 2022 Jul 21]

Chen XK, Wen SW, Yang Q, Walker MC. Adequacy of prenatal care and neonatal mortality in infants born to mothers with and without antenatal high-risk conditions. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;47(2):122–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17355301/ [cited 2022 Feb 20]

Gadson A, Akpovi E, Mehta PK. Exploring the social determinants of racial/ethnic disparities in prenatal care utilization and maternal outcome. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41(5):308–17. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28625554/ [cited 2022 Jul 26]

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2030. 2020. Available from: https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/pregnancy-and-childbirth/increase-proportion-pregnant-women-who-receive-early-and-adequate-prenatal-care-mich-08 [cited 2022 Apr 24]

Osterman MJK, Martin JA. Timing and adequacy of prenatal care in the United States, 2016. Natl Vital Stat Reports. 2016;67(3).

Rochelson B, Nimaroff M, Combs A, Schwartz B, Meirowitz N, Vohra N et al. The care of pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic - response of a large health system in metropolitan New York. J Perinat Med. 2020;48(5):453–61. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32432568/ [cited 2022 Jan 17]

Davis-Floyd R, Gutschow K, Schwartz DA, Pregnancy. Birth and the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States. Med Anthropol. 2020;39(5):413–27. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32406755/ [cited 2022 Feb 14]

Javaid S, Barringer S, Compton SD, Kaselitz E, Muzik M, Moyer CA. The impact of COVID-19 on prenatal care in the United States: qualitative analysis from a survey of 2519 pregnant women. Midwifery. 2021;98:102991.

Gutschow K, Davis-Floyd R. The Impacts of COVID-19 on US Maternity Care Practices: A Followup Study. Front Sociol. 2021;6. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34150906/ [cited 2022 Jan 17]

Adams C. Pregnancy and birth in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic: The views of doulas. Birth. 2021;1–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34296466/ [cited 2022 Jan 11]

Beeson T, Claridge A, Wojtyna A, Rich D, Minks G, Larson A. Pregnancy and childbirth expectations during COVID-19 in a convenience sample of women in the United States. J Patient Exp. 2021;8. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC8414620/ [cited 2022 Jul 28]

Altman MR, Gavin AR, Eagen-Torkko MK, Kantrowitz-Gordon I, Khosa RM, Mohammed SA. Where the System Failed: The COVID-19 Pandemic’s Impact on Pregnancy and Birth Care. Glob Qual Nurs Res. 2021;8:1–11. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33869668 [cited 2022 Feb 19]

Whipps MDM, Phipps JE, Simmons LA. Perinatal health care access, childbirth concerns, and birthing decision-making among pregnant people in California during COVID-19. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):1–13. Available from: https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03942-y [cited 2022 Feb 19]

Barbosa-Leiker C, Smith CL, Crespi EJ, Brooks O, Burduli E, Ranjo S et al. Stressors, coping, and resources needed during the COVID-19 pandemic in a sample of perinatal women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33648450/ [cited 2022 Jan 11]

Gur RE, White LK, Waller R, Barzilay R, Moore TM, Kornfield S et al. The Disproportionate Burden of the COVID-19 Pandemic Among Pregnant Black Women. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33007683/ [cited 2022 Jan 11]

Romero D, Manze M, Goldman D, Johnson G. The Role of COVID-19, Race and Social Factors in Pregnancy Experiences in New York State: The CAP Study. Behav Med. 2021;1–13. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34743679/ [cited 2022 Jan 11]

March of Dimes. Peristats | Healthy Moms Strong Babies. 2022. Available from: https://www.marchofdimes.org/peristats/calculations.aspx?reg=99&top=&id=23 [cited 2022 Feb 13]

Babitsch B, Gohl D, von Lengerke T. Re-revisiting Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Use: a systematic review of studies from 1998–2011. GMS Psycho-Social-Medicine. 2012;9. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC3488807/ [cited 2022 Jul 27]

Lean SC, Derricott H, Jones RL, Heazell AEP. Advanced maternal age and adverse pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(10). Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC5645107/ [cited 2022 Apr 11]

Cavazos-Rehg PA, Krauss MJ, Spitznagel EL, Bommarito K, Madden T, Olsen MA et al. Maternal age and risk of labor and delivery complications. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19(6):1202. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC4418963/ [cited 2022 Apr 11]

Fryer K, Delgado A, Foti T, Reid CN, Marshall J. Implementation of Obstetric Telehealth During COVID-19 and Beyond. Matern Child Health J. 2020;24(9):1104. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7305486/ [cited 2022 Jul 28]

Peahl AF, Smith RD, Moniz MH. Prenatal care redesign: creating flexible maternity care models through virtual care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223(3):389.e1. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7231494/ [cited 2022 Jul 28]

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Risk for COVID-19 Infection, Hospitalization, and Death By Race/Ethnicity. 2022. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html [cited 2022 Oct 15]

Restrepo BJ, Obesity Prevalence Among US. Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am J Prev Med. 2022;63(1):102–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2022.01.012 [cited 2023 Jul 7]

Melnick EM, Ganderats-Fuentes M, Ohri-Vachaspati P. Federal Food Assistance Program Participation during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Participant Perspectives and Reasons for Discontinuing. Nutrients. 2022;14(21). Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC9654117/ [cited 2023 Jul 7]

Villar J, Ariff S, Gunier RB, Thiruvengadam R, Rauch S, Kholin A et al. Maternal and Neonatal Morbidity and Mortality Among Pregnant Women With and Without COVID-19 Infection: The INTERCOVID Multinational Cohort Study. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(8):817–26. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/fullarticle/2779182 [cited 2023 Jul 7]

Acknowledgements

JL, BO, PH, JZ, XL reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) during the conduct of the study (3R01AI127203-5S2). PH also reported receiving grants from the Health Resources and Services Administration during the conduct of the study. No other disclosures were reported.

Funding

Research reported in this study was supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01AI127203-5S2. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Data for this study were provided by the South Carolina (SC) Department of Health and Environmental Control (DHEC) and the SC Office of Revenue and Fiscal Affairs. National Institutes of Health, DHEC and SC Office of Revenue and Fiscal Affairs had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JL and EFJ had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. JL, XL, BO, and PH acquired data. JL and EFJ drafted the manuscript. JL, JZ, PH assisted with statistical analysis. All authors conceptualized, designed the study, interpreted data, critically reviewed, and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of South Carolina and the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control, and followed procedures in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional review boards. Informed consent was waived by the University of South Carolina Institutional Review Board and the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control Institutional Review Board because this study used de-identified data from a statewide vital records birth certificate dataset and had no more than the minimal risk.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Julceus, E.F., Olatosi, B., Hung, P. et al. Racial disparities in adequacy of prenatal care during the COVID-19 pandemic in South Carolina, 2018–2021. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 23, 686 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-023-05983-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-023-05983-x