Abstract

Objective

Women who are late to prenatal care miss opportunities for health interventions and are at increased risk for pregnancy-related complications. Black women have the lowest rates of first trimester care compared with White or Latinx women. We sought to describe barriers to prenatal care experienced by race/ethnicity in a multi-site, prospective cohort.

Study Design

We performed a secondary analysis of the Community Child Health Research Network Study, a multi-site prospective cohort study of pregnant women from 2008 to 2012. Women were recruited at the time of delivery and followed prospectively for 2 years. Participants who experienced a repeat pregnancy in the 2-year follow-up period had a prospective assessment of prenatal care barriers. A multilevel mixed effects Poisson regression was performed to evaluate the association between race/ethnicity and number of prenatal barriers.

Results

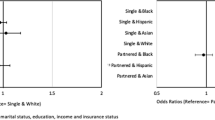

Of the 298 participants in the sample, 43% of Black, 35% of Latinx, and 23% of White participants reported barriers to prenatal care. After adjustment for confounders, Black and Latinx women reported almost twice as many barriers to prenatal care as White women (adjusted rate ratio 1.89 [1.2, 3.0]; 2.00 [1.1, 3.8], respectively).

Conclusion

In our analysis, multiparous Black and Latinx women reported encountering more barriers to prenatal care than White women. Additional reforms and policy change are needed at the clinic, local, and state levels to support women in accessing early quality prenatal care to achieve racial equity in prenatal care.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

American Academy of Pediatrics and American College of Obstrticians and Gynecologists. Guidelines for perinatal care. Elk Grove Village: AAP/ACOG; 2017. Retrieved from https://lccn.loc.gov/2017020397.

Partridge S, Balayla J, Holcroft CA, Abenhaim HA. Inadequate prenatal care utilization and risks of infant mortality and poor birth outcome: a retrospective analysis of 28,729,765 U.S. deliveries over 8 years. Am J Perinatol. 2012;29(10):787–93. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0032-1316439.

Krueger PM, Scholl TO. Adequacy of prenatal care and pregnancy outcome. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2000;100(8):485–92 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10979253. Accessed March 20, 2017.

Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, et al. Births: final data for 2007. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2010;58(24):1–85 https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr58/nvsr58_24.pdf. Accessed October 25, 2017.

Armstrong JH, Governor RS. Florida pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system 2011 surveillance data book. http://www.floridahealth.gov/statistics-and-data/survey-data/pregnancy-risk-assessment-monitoring-system/_documents/reports/prams2011.pdf. Accessed January 21, 2018.

Medicaid | Florida Department of Children and Families. http://www.myflfamilies.com/service-programs/access-florida-food-medical-assistance-cash/medicaid. Accessed April 26, 2018.

Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility Levels | Medicaid.gov. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/program-information/medicaid-and-chip-eligibility-levels/index.html. Accessed February 12, 2018.

State Profiles for Women’s Health | The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/interactive/womens-health-profiles/?activeState=Florida&activeCategoryIndex=3&activeView=data. Accessed March 2, 2018.

Aday LA, Andersen R. A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Serv Res. 1974;9(3):208–20. https://doi.org/10.3205/psm000089.

Penchansky R, Thomas JW. Definition and Relationship to Consumer Satisfaction. Med Care. 1981;XIX(2) http://www.jstor.org.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/stable/pdf/3764310.pdf. Accessed February 23, 2018.

Khan A, Bhardwaj S. Access to health care: a conceptual framework and its relevance to health care planning. Eval Heal Prof. 1994;17(1):60–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.1999.tb00414.x.

Phillippi JC, Roman MW. The motivation-facilitation theory of prenatal care access. J Midwifery Women’s Heal. 2013;58(5):509–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmwh.12041.

Daniels P, Noe GF, Mayberry R. Barriers to prenatal care among black women of low socioeconomic status. Am J Health Behav. 2006;30(2):188–98. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.30.2.8.

Johnson AA, El-Khorazaty MN, Hatcher BJ, et al. Determinants of late prenatal care initiation by African American women in Washington, DC. Matern Child Heal J. 2003;7(2):103–14. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023816927045.

Mazul MC, Salm Ward TC, Ngui EM. Anatomy of good prenatal care: perspectives of low income African-American women on barriers and facilitators to prenatal care. NMA Heal Inst. 2016;4:79–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-015-0204-x.

Roman LA, Raffo JE, Dertz K, Agee B, Evans D, Penninga K, et al. Understanding perspectives of African American Medicaid-insured women on the process of perinatal care: an opportunity for systems improvement. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21(S1):81–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-017-2372-2.

Tucker Edmonds B, Mogul M, Shea JA. Understanding low-income African American women’s expectations, preferences, and priorities in prenatal care. Fam Community Health. 2015;38(2):149–57. https://doi.org/10.1097/FCH.0000000000000066.

Ward TCS, Mazul M, Ngui EM, Bridgewater FD, Harley AE. “You learn to go last”: perceptions of prenatal care experiences among African-American women with limited incomes. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17(10):1753–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-012-1194-5.

Johnson AA, Hatcher BJ, El-Khorazaty MN, et al. Determinants of inadequate prenatal care utilization by African American women. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007;18(3):620–36. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2007.0059.

Slaughter-Acey JC, Caldwell CH, Misra DP. The influence of personal and group racism on entry into prenatal care among-African American women. Womens Health Issues. 2013;23(6):e381–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2013.08.001.

York R, Grant C, Tulman L, Rothman RH, Chalk L, Perlman D. The impact of personal problems on accessing prenatal care in low-income urban African American women. J Perinatol. 1999;19(1):53–60. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jp.7200052.

Meikle SE, Orleans M, ML W, Shain R, Gibbs RS. Women’s reasons for not seeking prenatal care: racial and ethnic factors. Birth. 1995;22(2):81–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-536X.1995.tb00564.x.

Byrd TL, Mullen PD, Selwyn BJ, Lorimor R. Initiation of prenatal care by low-income Hispanic women in Houston. Public Health Rep. 1996;111(6):536–40 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1381903/pdf/pubhealthrep00045-0066.pdf. Accessed May 31, 2018.

Tandon SD, Parillo KM, Keefer M. Hispanic women’s perceptions of patient-centeredness during prenatal care: a mixed-method studya. Birth. 2005;32(4):312–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0730-7659.2005.00389.x.

Fullerton JT, Nelson C, Bader J, Nelson C, Shannon R. Prenatal care in the Paso del Norte border region. J Perinatol. 2004;24(2):62–71. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jp.7211028.

Luecken LJ, Purdom CL, Howe R, Linda Luecken MJ, Professor A. Prenatal care initiation in low-income Hispanic women: risk and protective factors. Am J Health Behav. 2009;33(3):264–75.

Bengiamin MI, Capitman JA, Ruwe MB. Disparities in initiation and adherence to prenatal care: impact of insurance, race-ethnicity and nativity. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14(4):618–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-009-0485-y.

Rogers C, Schiff M. Early versus late prenatal Care in New Mexico: barriers and motivators. Birth. 1996;23(1):26–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-536X.1996.tb00457.x.

Mikhail BI. Perceived impediments to prenatal care among low-income women. West J Nurs Res. 1999;21(3):335–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/01939459922043910.

Downe S, Finlayson K, Walsh D, Lavender T. “Weighing up and balancing out”: a meta-synthesis of barriers to antenatal care for marginalised women in high-income countries. BJOG An Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;116(4):518–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.02067.x.

Ramey SL, Schafer P, DeClerque JL, et al. The preconception stress and resiliency pathways model: a multi-level framework on maternal, paternal, and child health disparities derived by community-based participatory Research. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19(4):707–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-014-1581-1.

Dunkel Schetter C, Schafer P, Lanzi RG, Clark-Kauffman E, Raju TNK, Hillemeier MM. Shedding light on the mechanisms underlying health disparities through community participatory methods: the stress pathway. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2013;8(6):613–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691613506016.

Johnson AA, Wesley BD, El-Khorazaty MN, et al. African American and Latino patient versus provider perceptions of determinants of prenatal care initiation. Matern Child Health J. 2011;2003(S1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-011-0864-z.

Meyer E, Hennink M, Rochat R, Julian Z, Pinto M, Zertuche AD, et al. Working towards safe motherhood: delays and barriers to prenatal care for women in rural and peri-urban areas of Georgia. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20:1358–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-016-1997-x.

Nepal VP, Banerjee D, Perry M. Prenatal care barriers in an inner-city neighborhood of Houston, Texas. J Prim Care Community Health. 2011;2(1):33–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/2150131910385944.

Piper JM, Mitchel EF, Ray WA. Presumptive eligibility for pregnant Medicaid enrollees: its effects on prenatal care and perinatal outcome. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(10):1626–30 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1615092/pdf/amjph00461-0076.pdf. Accessed October 5, 2018.

Research CGSC for HS. NC Health Workforce - North Carolina Health Professional Supply Data. https://nchealthworkforce.unc.edu/supply/. Published 2019. Accessed September 30, 2019.

Foundation THJKF. Medicaid and CHIP Income Eligibility Limits for Pregnant Women, 2003–2018. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/medicaid-and-chip-income-eligibility-limits-for-pregnant-women/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D. Published 2019. Accessed August 30, 2018.

Jarlenski MP, Bennett WL, Barry CL, Bleich SN. Insurance coverage and prenatal care among low-income pregnant women: an assessment of states’ adoption of the “unborn child” option in Medicaid and CHIP. Med Care. 2014;52(1):10–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000020.

Ross DC, Horn A, Marks C. Health Coverage for Children and Families in Medicaid and SCHIP: State Efforts Face New Hurdles.; 2008. https://www.kff.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/7740.pdf. Accessed September 30, 2019.

Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid and CHIP Income Eligibility Limits for Pregnant Women as a Percent of the Federal Poverty Level. https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/medicaid-and-chip-income-eligibility-limits-for-pregnant-women-as-a-percent-of-the-federal-poverty-level/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D. Published 2019. Accessed September 30, 2019.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the original principal investigators, which included C. S. Minkovitz in Baltimore, M. Shalowitz in Chicago, C. Hobel in Los Angeles, J. Thorp in North Carolina, and S. L. Ramey and L. Klerman in Washington, D.C.

Funding

This secondary analysis was of the Child Community Health Network Study, which was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (U HD44207, U HD44219, U HD44226, U HD44245, U HD44253, U HD54791, U HD54019, U HD44226-05S1, U HD44245-06S1, R03 HD59584) and the National Institute for Nursing Research (U NR008929).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fryer, K., Munoz, M.C., Rahangdale, L. et al. Multiparous Black and Latinx Women Face More Barriers to Prenatal Care than White Women. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 8, 80–87 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00759-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00759-x