Abstract

Africa has the highest rates of maternal deaths globally which have been linked to poorly functioning health care systems. The pandemic revealed already known weaknesses in the health systems in Africa, such as workforce shortages, lack of equipment and resources. The aim of this paper is to review the published literature on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and child health in Africa. The integrative review process delineated by Whittemore and Knafl (2005) was used to meet the study aims. The literature search of Ovid Medline, CINAHL, PubMed, WHO, Google and Google scholar, Africa journals online, MIDIRS was limited to publications between March 2020 and May 2022. All the studies went through the PRISMA stages, and 179 full text papers screened for eligibility, 36 papers met inclusion criteria. Of the studies, 6 were qualitative, 25 quantitative studies, and 5 mixed methods. Thematic analysis according to the methods of Braun and Clark (2006) were used to synthesize the data. From the search the six themes that emerged include: effects of lockdown measures, COVID concerns and psychological stress, reduced attendance at antenatal care, childhood vaccination, reduced facility-based births, and increase maternal and child mortality. A review of the literature revealed the following policy issues: The need for government to develop robust response mechanism to public health emergencies that negatively affect maternal and child health issues and devise health policies to mitigate negative effects of lockdown. In times of pandemic there is need to maintain special access for both antenatal care and child delivery services and limit a shift to use of untrained birth attendants to reduce maternal and neonatal deaths. These could be achieved by soliciting investments from various sectors to provide high-quality care that ensures sustainability to all layers of the population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Key messages

Preparedness and response support to countries with high maternal and child mortality rates will be critical now than ever to reduce the negative impact of the current global pandemic.

Healthcare systems need to be strengthened to prioritize maternal and child health services during and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

This could be achieved by soliciting investments from various sectors to provide quality care that ensures sustainability to all layers of the population.

Introduction

The specific effects of SARS-CoV-2 on maternal health include reduced accessibility to health care by women and children because of the competing needs for intensive health care services of corona virus diseases-2019 (COVID-19) patients; health care infrastructures, medical equipment, and deliverables became overstretched and inadequate to meet the needs of all patients with women and children particularly affected.

Throughout history, Africa has often faced epidemics resulting in many deaths, including Lassa fever, polio, measles, tuberculosis and human immunodeficiency virus and Ebola disease [1]. The latter was more notable in West Africa. SARS-CoV-2, commonly known as COVID-19, was first discovered in Wuhan China in December 2019 but spread globally with the first African case reported in Egypt on the 14th of February 2020. By the end of first week of March 2020, other African countries including Algeria, Cameroon, Egypt, Morocco, Nigeria, Senegal, South Africa, Togo, and Tunisia recorded their first cases with most index cases originating from Europe [2]. The World Health Organisation (WHO) declared the virus a global pandemic on the 11th of March 2020. Countries developed various related strategies including lockdowns with stringent rules.

The vulnerability of the health care systems in Africa have been exposed by past pandemics, such as Ebola, Athenian plague, Black death, the Seven-Cholera Pandemic, Justinian plague, HIV/AIDS, and Swine flu. During these pandemics there was a decline in access to healthcare during pregnancy and childbirth leading to increased risk of maternal morbidity and mortality, which further weakened the health systems [3,4,5,6,7]. The global measures implemented by different countries to control the spread of COVID-19 has had adverse effects on citizens. Some studies reported that in Africa the COVID-19 outbreak caused disruption and decline in maternaland child health services such as antenatal care (ANC), delivery, post-natal care (PNC), family planning and vaccinations [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15] linked to barriers created by lack of personal protective equipment (PPE), shortage of human resources, long waiting times and others. Measures to overcome the situation caused disruptions in routine ANC as accessibility was difficult, lack of transportation, increased poverty as breadwinners were jobless, informal jobs could not thrive among other impaired circumstances. These were impediments to pregnant women trying to access to health facilities [14, 16]. Above all, health facilities were occupied with the pandemic and its related diseases. During the first wave of the pandemic, health facilities focused solely on COVID-19 to the exclusion of all other conditions hence maternal health care (MHC) services uptake fell steadily during the pandemic [13]. This decline was reported in eight sub-Saharan African countries where countries experienced MHC service disruption for at least a month with the magnitude and durations differing among countries [12].

Even though COVID-19 pandemic is not gender selective, maternal health in Africa may have been particularly affected by these measures [4, 17]. Hence this integrative review aimed to assess the impact of COVID-19 on maternal and child health service in Africa.

Methods

Methodology

The integrative review process delineated by Whittemore and Knafl [18] was used to meet the study aims. Integrative reviews make use of not only quantitative and qualitative studies but survey and technical reports in the grey literature that may be pertinent [18]. The method of this review followed five phases: problem identification, literature search, data evaluation, data analysis, and presentation which is a display of the results in tables and figures.

Search strategy and selection procedure

A search of Ovid Medline, CINAHL, PubMed, WHO, Google and Google scholar, Africa journals online, MIDIRS, was performed using the following key terms: ‘COVID-19’, ‘Africa’, ‘maternal health’, ‘pandemic’, 'child health', ‘COVID-19 coronavirus’ OR ‘SARS-Cov-V-2’ AND ‘maternal health’ OR “pregnancy OR ‘perinatal’. All the studies went through the PRISMA stages, that is, identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion [19].

Inclusion criteria

Our search was limited to peer-reviewed research studies or grey literature which used systematic approaches to surveys or data conducted in Africa and published in English between March 2020 and May 2022. Reference lists of selected full texts were screened for additional relevant papers.

Exclusion criteria

Conferences/updates, commentaries, or personal interviews without a clear methodology for reported data and research studies not conducted in Africa, not published in English language and not within the time frame were excluded.

Data extraction

Two authors (E.K.S & M.O) independently reviewed all studies after duplicates were removed for inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any disagreements in assessment were resolved by discussion and mutual agreement. For each study included, we recorded the last name of author(s), year of publication, country, title, focus/aim, design/methodology, data collection method, sample size and key findings.

Data synthesis

Thematic analysis according to the methods of Braun and Clark [20] were used to synthesize the data. The two authors independently read all included papers and coded key elements. Together they identified patterns from the codes from which key themes emerged. Literal interpretation of the data yielded the themes.

Results

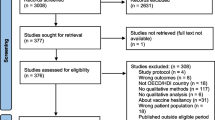

Among the 179 full text papers screened for eligibility, 36 papers met inclusion criteria (see Fig. 1). Of the studies, 6 were qualitative, 25 quantitative studies, and 5 mixed methods. (See Table 1). The studies were retrieved from 4 African regions with the greatest number from East Africa and four from several sub-Saharan African countries (see Table 2). Synthesis from the relevant studies revealed six relevant themes: effects of lockdown measures, COVID concerns and psychological stress, reduced attendance at antenatal care, childhood vaccination, reduced facility-based births and increase maternal and child mortality. (Table 3).

Effects of lockdown measures

A primary strategy used to curtail the spread of the pandemic globally was lockdown. Although pregnant mothers were allowed to access health facilities during emergencies, they had challenges accessing the health facilities during the curfew [38]. The primary source of transportation for most women to reach birth centres is either commercial or private transport which was banned in Kenya with few public ambulances operating during curfew hours [16]. Movement restrictions and transport challenges were also identified as barriers to maternal health service uptake in Ethiopia [8, 14]. Similarly, the findings of cross-sectional survey of 1241 Nigerian women by Balogun et al., [25] and a mixed method study in Ethiopia [8] showed that lockdowns and lack of transportation were barriers to accessing MHC services.

In an effort to get citizens to comply with the lockdown rules, some African countries used the law enforcement agents who often intimidated and harassed citizens so that some were afraid of going out for what is considered essential service [48]. Among a study of four sub-Saharan countries, not only lack of transportation during epidemic peaks but the high cost of transportation limited access to healthcare [26]. According to the report of White Ribbon Alliance (WRA), at least one pregnant woman died in Uganda as a direct result of lack of transportation amid the lockdown [16]. Others observed that pregnant women could not get to the health facility due to lockdown measures and lack of transportation[21 23,24,25,26,27].

A survey conducted in Kenya revealed that women and girls reported the curtailment of economic activities affected their ability to pay for services and therefore limited healthcare access [16]. This was similar in Ethiopia where economic suffering prevented women from being able to pay for transportation [8]. A cross-sectional study of 1600 pregnant women in Democratic republic of Congo between March 2020–May 2021 identified similar issues [30]. This study showed that lack of money along with vaccine hesitancy were some of the reason’s women did not access MHC services [30].

The lack of access to health services due to lockdown measures compelled pregnant women to acquire more knowledge of the pandemic and preventive measures. The increased level of knowledge was attributed to media campaign, which aimed to educate citizens on preventive measure to reduce transmission of the virus [35]. Pregnant women’s knowledge and practice of preventive measures against COVID-19 in a low-resource African setting deduced that whilst awareness level of most respondents concerning preventive measures was sufficient, it was observed that the level of practice of these preventive measures was inadequate [35]. On the other hand, a study in Ethiopia found women who practiced infection preventive measures and wore face masks were 2–5 times more likely to access MHC than those who did not [14].

COVID concerns and psychological stress

Several studies documented women’s concerns to access MCH services for themselves and their children due to concerns of acquiring SARS-CoV-2 [14, 33, 39, 44]. A rapid gender analysis in West Africa found a reduction in access to maternal health services due to doubt about health of healthcare workers and the fear of succumbing to COVID-19 [33]. Temesgen and colleagues [14] identified fear of contacting SAR-CoV-2 as a significant barrier in maternal health service uptake in Ethiopia. This was echoed by another four-country study by Banke-Thomas et al., [26]. Several studies specifically cited women’s concerns about the lack of PPE for both patients and staff [14, 31]. A Nigerian qualitative study identified barriers to accessing MHC included both women’s concerns about lack of PPE and shortage of manpower [22]. Interestingly, a study from Southwest Ethiopia among 402 pregnant women identified important delays in seeking care but fear of contagion or other aspects of the pandemic were not among them [21].

Lack of adequate staffing was due to a combination of lack of personnel out sick due to COVID or concerns about contacting the disease [22, 34] and lockdown effects of limiting transportation and economic activity. This resulted in lack of preparedness by health workers, prioritization of essential services, and long wait times at the hospitals all of which were identified as barriers to accessing maternal, newborn and child health services during the first wave of COVID-19 [22]. Similarly mixed method study among skilled healthcare providers in six referral hospitals in Guinea, Nigeria, Tanzania, and Uganda to assesses how maternal healthcare was rendered identified inadequate knowledge about COVID-19, lack of infection prevention and control training, and difficulties reaching workplace as barriers in providing MHC services [41]. However, shortage of PPE and lack rapid testing for women suspected with COVID-19 were challenges that continued past the first wave [41].

Effects of the pandemic on psychological health have been well documented worldwide. Nwafor and colleagues [36] measured depression and anxiety in 456 pregnant women attending antenatal care in Nigeria during the ongoing pandemic. The rate of moderate or more severe depression was 27 and 22% rated as having moderate to severe stress.

Reduced attendance at antenatal care

Access to high quality ANC potentially jeopardized the safety of parturient women during pregnancy during episodes of high prevalence of COVID 19 cases. COVID-19 caused distortion in health care services leading to non-regular attendance during ANC in rural and urban areas [26]. A mixed method study in eight health facilities in Ethiopia comparing the service utilisation trends in the first 6 months of COVID-19 with the corresponding time and data points of the preceding year showed reduced ANC visits (208.9 to 181.7/month, p = 0.433) and under 5 visits (225.0 to 139.8/month, p = 0.007) [8]. An assessment of effect of the pandemic on the uptake of MHC in Somali region of Ethiopia, through a retrospective chart review revealed that the mean number of ANC pre-pandemic was 4088 and intra-pandemic was 3498., reflecting a 14% decline in ANC attendance [37] . This decline in ANC visits was corroborated by a national study using reproductive, maternal, and newborn health services data from governmental health facilities in Ethiopia during a similar time period [11]. Similarly, there was sharp decreased in antenatal clinic attendance in Uganda which was already low pre-covid with an increase in pregnancy related problems such haemorrhage, and caesarean section [28]. This was particularly true during the first phase between March and June not only in Uganda but also Nigeria [26]. Similar sharp decreases in ANC visits were observed in eight sub-Saharan countries [12].

Reasons for the low ANC attendance recorded during the COVID-19 period included inappropriate service delivery, pandemic preventive measures, shortage of medical supplies, and staff workload [31, 45]. As documented by previous themes, pregnant mothers feared attending ANC would increase their probability of contracting COVID-19 [39]. Similarly, a facility-based cross-sectional study conducted between February and August 2020, among 389 pregnant women found that diversion of maternity health-care service to COVID-19 related services, fear of COVID-19 infection, and transport inaccessibility were notable factors which contributed to the low antenatal care service use by pregnant women in Ethiopia [44].

An interrupted-times series analysis compared 1189 women who delivering in healthcare facilities before the COVID-19 pandemic (September 2019–January 2020) and 540 women who delivered during the pandemic (July through November 2020) [32]. The analysis found that women who delivered during COVID-19 had a 72% higher odds of delayed ANC commencement compared to pre-pandemic data (OR 1.72, 95% CI 1.24 to 2.37). Moreover, 47% of women who delivered during COVID-19 stated that the pandemic affected their capability to access ANC [32]. A study using a similar design in Ghana, documented a 25% reduction in women attending at least 4 ANC visits during the pandemic compared to pre-pandemic [23]. A similar pattern was identified by Banke-Thomas and colleagues [26] among four sub-Saharan countries but mostly during the first wave (March to June 2020) and the second wave (from last quarter of 2020 through Feb 2021). Conversely, in a comparative study in Ethiopia to compare effect of the COVID-19 pandemic preparation and response on essential health services in primary and tertiary healthcare facilities found no significant variation in ANC visits. The study reported mean ANC visits of 910 pre-COVID and 941 during the pandemic period. However, there was approximately 38% decline of the annual mean visits in April (572) with an increase in visits between May and June by 128% (114) [29] indicating delayed care.

Childhood vaccination

The COVID-19 pandemic has had an impact on childhood vaccination. There was significant decline in Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) and pentavalent-3 vaccinations during the early period of the pandemic in Ethiopia [9, 10]. Pires et al., [40] investigated whether increased community awareness of the prepared state of a general hospital and health centre for COVID-19 in Mozambique would have a differential effect on use of maternal and child health services compared to 2019 and a comparable hospital and health centre outside the intervention campaign area. There was no effect from the community awareness program and both intervention and control settings experienced as decrease in first antenatal visits in the first trimester of 26 and 12%, respectively. There was also a decline on the percentage of children completing their vaccinations of 16–18% [40]. Similarly, there was sharp 16% decrease in total newborn vaccinations in an interrupted time series study in Ethiopia comparing pre-pandemic and pandemic time periods (739.5 compared to 528.5) [11, 13]. Notably, the utilization of MHC services and uptake of vaccinations declined during COVID-19 outbreak in Rwanda [15] and Uganda [24]. A similar interrupted time series study in eight sub-Saharan countries found child vaccinations were the most affected health service [12]. An estimated cumulative deficit of 328,961 third-dose pentavalent vaccinations during the 5 months in these countries was recorded [12].

Reduced facility-based births

The easiest metrics to assess the COVID pandemic’s effect on access to MCH services is the number of births in facilities with skilled birth attendants. Most practically, the government issued curfews may have limited pregnant women’s power to travel and access health services during labour. Similarly, fear of being harassed by security agents reduced health facility births [16]. A WHO survey of 11 African countries showed facility-based births were reduced in 45% of the countries between November to December 2021 compared to a comparable time period pre-pandemic [46]. Additionally, two interrupted time series studies in Ethiopia and among eight other sub-Saharan Africa countries found significant decline in facility delivery births [12, 13].

However, facility birth decline was not universal. Bekele and colleagues reported reduced facility delivery rates in Ethiopia which was not statistically significant (90.7 to 84.2/month, p = 0.776) [8] and Enbiale and colleagues [29] also in Ethiopia did not find a significant decline. A cross-sectional study at Mpilo - Zimbabwe Central Hospital compared routine monthly maternal and perinatal statistics three months before and after COVID-19 emergency measures were implemented. The study did not find a significant decrease in births but there was a statistically significant decline in the proportion of births among women booked to deliver at the hospital from a mean of 41.6% (SD ± 1.1) to 35.8% (SD ± 4.3) (p = 0.03) [42]. The magnitude of decline in facility births ranged from a low of 3% in Uganda [24] to 15%-point decrease in 5 regions of Ghana [23]. Studies in both Somalia and Ethiopia recorded over a 20% decrease in skilled birth attendant births [11, 37]. A study in six regions of Ethiopia covering 91% of the population, found 77% reduced risk of facility-based births during the pandemic compared to pre-pandemic among urban women but no difference in facility-based births among rural women [47]. This resulted to a rise in facility stillbirth (14% vs 21.8%) and neonatal death (33.1% vs 46.2%) [11]. The facility delivery disparity rate seen here from the narrative of Ethiopia could be attributed to cultural practices such encouraging home delivery, fear and anxiety associated with the pandemic, misinformation by media, lockdowns, health system resilience, and no support from healthcare workers [8, 13, 29].

Increased maternal and child mortality

There is some evidence that delays in care due to numerous issues related from COVID-19 increased maternal mortality. A WHO survey among 11 African countries identified an average 16% increase in health facility maternal deaths February to May 2020 which decreased to an 11% increase in 2021 [46]. Correspondingly, secondary data analysis from government portals in Uganda from 2019/20 financial year supplemented by analysis of relevant article published up May 2021 found maternal mortality increased by 7.6% during COVID-19 period [24]. On the other hand, a study using the Kenyan Health Information System comparing 2019 data to March to June 2020 data did not show any differences in the maternal mortality ratio except for noting a trend in an increase of adolescent maternal deaths from 6.2 to 10.9% [43].

There is some evidence of increased maternal morbidity during COVID restrictions. Bikwa et al. [27] carried out a retrospective review of maternal audit to determine the impact of COVID-19 on maternal and perinatal outcomes in Harare, Zimbabwe. They compared data from March–August 2020 with data from March–August 2019 which showed a decreased uptake of maternal health services in 2020 and increased maternal morbidities of uterine rupture possibly due to 30% decreased odds of caesareans.

Perinatal and neonatal outcomes also may have worsened. Bikwa et al.’s [27] study in Harrare also found increased odds of both stillbirths and neonatal deaths. Kassie and colleagues [11] identified a sharp rise in facility stillbirth (14% vs 21.8%) and neonatal deaths (33.1% vs 46.2%) in their study in Ethiopia. The study done in Mpilo-Zimbabwe Central Hospital did not find an increase in early neonatal deaths [42].

Discussion

Our integrative review identified significant effects of the pandemic on access to and the quality of care available to pregnant women in all major regions of Africa as well as delayed vaccinations among children. Pregnant women not only had trouble accessing services because of transportation restriction and high cost of transport but also because maternal health services were curtailed due to lack of healthcare workers, either due to illness, lack of PPE, or shifting personnel to care for COVID-infected patients [49]. The lack of appropriate healthcare due to the pandemic is even more important given the low rates of vaccination in Africa and the higher rates of adverse maternal outcome due to preeclampsia [50], gestational diabetes [51] and possibly thrombotic events as a consequence of additional risk factors including pregnancy itself and surgical procedures performed during labour or after delivery [52].

There is evidence that delayed or curtailed care resulted in increased maternal morbidity and mortality as well as increased neonatal morality [11, 16, 24, 27, 43, 46]. The full effect of maternal lives lost from the shift from facility to home births may not yet be appreciated due to the slow reporting for maternal deaths at home [46].

Our results on the effects of COVID on worsening maternal health echo the findings of a larger global systematic review of both low- and high-income countries with the exception of preterm births which only increased for high income countries [53]. However, unlike that review of mixed income countries which did not find significant differences in maternal morbidities or stillbirths, our review found evidence that weakened health facilities and changes to usual care from lockdown measures had an adverse effect on maternal and neonatal outcomes among some African countries. A review by Kotlar et al., [54], conclude that on one hand, when compared with non-pregnant women, risk of COVID-19 infection was not higher among pregnant women. On the other hand, pregnant women with COVID-19 symptoms are more likely to experience adverse outcomes than their non-pregnant counterparts [54].

Both high- and low-income countries have identified worsening of people’s mental health during the pandemic [55]. Several studies have documented the pandemic may have had a differential impact on women due to not only loss of employment but the burden of other responsibilities, such as running the household, general caring for children with the added role of taking on educational tasks [55]. A systematic review related to mental health effects of COVID on pregnant and lactating women found from studies in middle- and high-income countries, high rates of anxiety, depression, and social dysfunction [54, 56]. This echoes the findings in the single study in our integrative review that addressed the mental health effects among pregnant and postpartum women in Nigeria which documented a rate of severe depression of 22% and moderate to severe anxiety of 27% [36]. Although these authors did not report a comparable baseline rate of depression among Nigerian pregnant women, a global systematic review reported a baseline rate of 15% indicating a potentially significant effect of the COVID-19 epidemic on pregnant women’s mental health [57]. Socially, stigmatisation is a vital facet of infectious diseases such as leprosy, severe acute respiratory syndrome and AIDS [58]. In a study by Strong and Schwartz [59], expectant women were stigmatised by denying them access to services during Ebola epidemic by healthcare workers for the fear of being infected with the disease.

An important finding from Almeida et al., [55] on the differential effect of COVID on women was the importance of social support as a mediator in dampening the effects of the pandemic on women’s mental health. Some governments in African countries failed to put in place adequate measures to bolster social support to mitigate the negative fallout of the lockdown measures, such as loss of daily income by low-income families in the informal sector, psychological and social effects on women and children, security threats to lives and properties, and other criminal activities [16, 35, 38]. An important lesson for the future is that governments need to better analyse the costs and benefits of different actions in preparing for the next epidemic. Also, better methods of clear and transparent messaging are essential so that people do not lose trust in what they are hearing from government messaging.

The COVID-19 lockdown showed that the measures put in place was not fool proof as other ingredients should have been integrated into the arrangements. Most of the studies reported that measures to prevent and/or decrease the spread of SARS-CoV-2 infection such as curfews and inflexible law enforcement agents, limited access to needed medical care, transport curtailment, total closure of government offices and private businesses, closure of airports were not welfare considered and people centred in implementation [14, 16, 38]. Additionally, the pandemic revealed already known weaknesses in the health systems in Africa, such as workforce shortages, lack of equipment and resources – particularly PPE, and lack of suitable training of personnel. The needed shift of resources to caring for very ill COVID patients meant fewer resources for pregnant and labouring women [22, 49]. Recommendations to deal with epidemic related issues in the future include a need to develop plans ahead of time, methods to limit exposure of health personnel through adequate training in the use of PPE and adequate availability of PPE but also conserving PPE to be used only when needed [49]. Additionally, there needs to be a focus on maintaining health personnel’s well-being through the provision of resources, such as childcare and meal preparation, as well as psychological support to manage the stress of working during such as crisis [49]. Also, governments should create a buffer fund with legislative support to enable adequate and timely provision of financial and social and health support services to vulnerable groups and low-income families that depend on daily income [60, 61]. Governments need to improve funding of primary health care and introduce robust mechanisms to respond to health emergencies and crises [62, 63]. Funding and vaccine policies are needed for pregnant women in Africa because there is evidenced showing post-infection maternal SARS-CoV-2 humoral immunity decreases quickly during pregnancy, resulting in small or vague protective antibody for a substantial proportion of pregnant women. Moreover, a single boosting dose vaccine induced a strong rise in protective antibody for mother and newborn [64].

One of the most difficult issues is how to recruit and train needed personnel during an epidemic since unlike high resourced countries with many more health providers per population, in general African countries are already understaffed. A fuller examination of the efficiency and cost of the approach adopted by some countries of recruiting and training unemployed health workers and incentivizing public health workers is needed [65].

Several studies confirmed a decrease in ANC and skilled birth attendants leading to an increase in pregnancy-related problems and decrease in immunizations [23, 26, 28, 32, 38, 44]. Reduced attendance at ANC was a reality due to the public health concerns of the disease being spread among groups of people. However, ANC plays a crucial role in maintaining the health of pregnant women and their foetuses. One option might be establishing “mid-point clinics” to ensure proximity to health facilities but overcomes the challenges of inadequate space at health facilities, and reduces the burden of transportation and other lockdown measures that served as hindrances to accessing health facilities during an emergency.

Limitations

This focussed mainly on papers published in the English language. Some papers from Francophone and Lusophone African not publish in English with no available English translation were automatically excluded. As already noted, the review included papers published between March 2020 and May 2022 because the first recorded COVID case in Africa was on the 14th of February 2020. We acknowledge that only paper [36] made reference to mental health in this review. However, it is important to note this was an unintentional discovery. Maternal mental health was not included as a search term for this review.

Conclusion

The already existing limited access to quality maternal healthcare was exacerbated by the pandemic. While it is important to understand the extent to which women and their infants are susceptible to COVID-19, it is also crucial to comprehensively understand how the pandemic influenced other factors which affected access to quality and safe care, either directly or indirectly. Efforts need to be made to ensure that basic maternal health needs of women such as access to up-to-date information, quality care, and availability of transportation among others are not ignored any at time. Healthcare systems need to be strengthened to prioritize maternal and child health services during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. This could be achieved by soliciting investments from various sectors to provide high-quality care that ensures sustainability to all layers of the population. As noted by Ameyaw et al., [66], training and motivating healthcare providers in the use of remote approaches such as telemedicine and phone-based referral network could go a long way in securing women’s confidence during a pandemic period.

Abbreviations

- WHO:

-

World Health Organisation

- AIDS:

-

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndromes

- ANC:

-

Ante-Natal Care

- BCG:

-

Bacillus Calmette-Guerin

- COVID-19:

-

Corona Virus Diseases-2019

- HIV:

-

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- MHC:

-

Maternal Health Care

- OECD:

-

Organisation for Economic Co-operation Development

- PNC:

-

Post-Natal Care

- PPE:

-

Personal Protect

- ive:

-

Equipment

- WHO:

-

World Health Organisation

- WRA:

-

White Ribbon Alliance

References

Loembé MM, Tshangela A, Salyer SJ, Varma JK, Ouma AEO, Nkengasong JN. COVID-19 in Africa: the spread and response. Nat Med. 2020;2020(26):999–1003. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0;961-x.

Nextstrain Team. Genomic epidemiology of novel coronavirus - Africa-focused subsampling Nextstrain. n.d. https://nextstrain.org/ncov/africa?l=clock&p=grid. Accessed 4 April 2020.

Sochas L, Channon AA, Nam S. Counting indirect crisis-related deaths in the context of a low-resilience health system: the case of maternal and neonatal health during the Ebola epidemic in Sierra Leone. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32:32–9.

Riley T, Sully E, Ahmed Z, Biddlecom A. Estimates of the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on sexual and reproductive health in low- and middle-income countries. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2020;46:73–6.

Wang H, Wolock TM, Carter A, Nguyen G, Kyu H, Gakidou E. Estimates of global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and mortality of HIV, 1980–2015: the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet HIV. 2016;3(8):361–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2352-3018(16)30087x.

Adams P. Risks of Home Birth Loom for Women in Rural Africa Amid Lockdowns. 2020 https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2020/06/12/873166422/risks-of-home-birth-loom-fo r-women-in-rural-Africa-amid-the-lockdowns. Accessed 8 March 2020.

Sampath S, Khedr A, Qamar S, Qamar S, Tekin A, Singh R, et al. Pandemics throughout the History. Cureus. 2021;13:9. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.18136.

Bekele C, Bekele D, Hunegnaw BM, Van Wickle K, Gebremeskel FA, Korte M, et al. Impact of the COVID- 19 pandemic on utilisation of facility- based essential maternal and child health services from march to august 2020 compared with pre- pandemic march–august 2019: a mixed- methods study in north Shewa zone, Ethiopia. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e059408. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-059408.

Carter ED, Zimmerman L, Qian J, Roberton T, Seme A, Shiferaw S. Impact of the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic on coverage of reproductive, maternal, and newborn health interventions in Ethiopia: a natural experiment. Front Public Health. 2022;10:778413. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.778413.

Gebreegziabher SB, Marrye SS, Kumssa TH, Merga KH, Feleke AK, Dare DJ, et al. Assessment of maternal and child health care services performance in the context of COVID-19 pandemic in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: evidence from routine service data. Reprod Health. 2022;19:42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-022-01353-6.

Kassie A, Wale A, Yismaw W. Impact of coronavirus Diseases-2019 (COVID-19) on utilization and outcome of reproductive, maternal, and newborn health Services at Governmental Health Facilities in Southwest Ethiopia, 2020: comparative cross-sectional study. Int J Women's Health. 2021;13:479–88. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S309096.

Shapira G, Ahmed T, Drouard S, Amor Fernandez P, Kandpal E, Nzelu C, et al. Disruptions in maternal and child health service utilization during COVID-19: analysis from eight sub-Saharan African countries. Health Policy Plan. 2021;36(7):1140–51. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czab064.

Tefera B, Tariku Z, Kebede M, Mohammed H. A comparative trend analysis of maternal and child health service utilization before and during Covid-19 at Dire Dawa administration public health facilities. Ethiopia; 2021. Research Square 2022. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1348661/v1

Temesgen K, Wakgari N, Tefera B, Tafa B, Alemu G, Wandimu F, et al. Maternal health care services utilization in the amid of COVID-19 pandemics in west Shoa zone, Central Ethiopia. Plos one. 2021a;16(3). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249214.

Wanyana D, Wong R, Hakizimana D. Rapid assessment on the utilization of maternal and child health services during COVID-19 in Rwanda. Public Health Action. 2021;11(1):12–21. https://doi.org/10.5588/pha.20.0057.

Ateva, E. COVID-19 Curfew restrictions impact reproductive, maternal, and newborn health and rights worldwide. 2020 https://web.archive.org/web/20200610195440/https://www.whiteribbonalliance.org/2020/06/08/covid-19-curfew-restrictions-impact-women-and-newborns-worldwide/ Accessed 5 August 2020.

Graham WJ, Afolabi B, Benova L, Campbell OMR, Filippi V, Nakimuli A, et al. Protecting hard-won gains for mothers and newborns in low-income and middle-income countries in the face of COVID-19: call for a service safety net. British medical journal. Glob Health. 2020;5:e002754. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002754.

Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52(5):546–53.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Plos med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Abdisa DK, Jaleta DD, Feyisa JW, Kitila KM, Berhanu RD. Access to maternal health services during COVID-19 pandemic, re-examining the three delays among pregnant women in Ilubabor zone, Southwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Plos one. 2022;17(5):e0268196. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0268196.

Akaba GO, Dirisu O, Okunade KS, Adams E, Ohioghame J, Obikeze OO, et al. Barriers and facilitators of access to maternal, newborn and child health services during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic in Nigeria: findings from a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):611. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-07996-2.

Asuming PO, Gaisie DA, Agula C, Bawah AA. Impact of COVID-19 on maternal health seeking in Ghana. J Int Dev. 2022;34(4):919–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3627.

Atim MG, Kajogoo VD, Amare D, Said B, Geleta M, Muchie Y, et al. COVID-19 and health sector development plans in Africa: the impact on maternal and child health outcomes in Uganda. Risk Management & Healthcare Policy. 2021;14:4353–60.

Balogun M, Banke-Thomas A, Sekoni A, Boateng GO, Yesufu V, Wright O, et al. Challenges in access and satisfaction with reproductive, maternal, new-born and child health services in Nigeria during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional survey. Plos one. 2021;16(5):e0251382. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0251382.

Banke-Thomas A, Semaan A, Amongin D, Babah O, Dioubate N, Kikula A, et al. A mixed-methods study of maternal health care utilisation in six referral hospitals in four sub-Saharan African countries before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7:e008064. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-00806.

Bikwa Y, Murewanhema G, Kanyangarara M, Madziyire MG, Chirenje ZM. Impact of COVID-19 on maternal and perinatal outcomes in Harare, Zimbabwe: a comparative maternal audit. J Glob Health Rep. 2021;5:e2021093. https://doi.org/10.29392/001c.28995.

Burt J, Ouma J, Amone A, Aol L, Sekikubo M, Nakimuli A, et al. Indirect effects of covid-19 on maternal, neonatal, child, sexual and reproductive health services in Kampala, Uganda. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(8). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006102.

Enbiale W, Abdela SG, Seyum M, Bedanie Hundie D, Bogale KA, et al. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic preparation and response on essential health Services in Primary and Tertiary Healthcare Settings of Amhara region, Ethiopia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2021;105(5):1240–6. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.21-0354.

Galle A, Kavira G, Semaan A, Françoise MK, Benova L, Ntambue A. Utilisation of services along the continuum of maternal healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic in Lubumbashi, DRC: findings from a cross-sectional household survey of women. PREPRINT (Version 1) Research Square; 2022. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1454838/v1.

Hailemariam S, Agegnehu W, Derese M. Exploring COVID-19 related factors influencing antenatal care services uptake: a qualitative study among women in a rural community in Southwest Ethiopia. J Prim Care Community Health. 2021;12:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/2150132721996892.

Landrian A, Mboya J, Golub G, Moucheraud C, Kepha S, Sudhinaraset M. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on antenatal care utilisation in Kenya: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e060185. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-060185.

Laouan, F. Rapid Gender Analysis - COVID-19: West Africa. 2020. https://reliefweb.int/report/benin/rapid-gender-analysis-covid-19-west-africa-april-2020. Accessed 10th June 2020.

Mongbo Y, Sombié I, Dao B, Johnson EAK, Ouédraogo L, Tall F, et al. Maintaining continuity of essential reproductive, maternal, neonatal, child and adolescent health services during the COVID-19 pandemic in francophone West Africa. Afr J Reprod Health. 2021;25(2):76–85. https://doi.org/10.29063/ajrh2021/v25i2.7.

Nwafor JI, Aniukwu JK, Anozie BO, Ikeotuonye AC, Okedo-Alex IN. Pregnant women’s knowledge and practice of preventive measures against COVID-19 in a low-resource African setting. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2020;150(1):121–3. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.13186.

Nwafor JI, Okedo-Alex IN, Ikeotuonye AC. Prevalence and predictors of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms among pregnant women during COVID-19-related lockdown in Abakaliki. Nigeria Malawi Med J. 2021;33(1):54–8. https://doi.org/10.4314/mmj.v33i1.8.

Oladeji O, Oladeji B, Farah AE, Ali YM, Ayanle M. Assessment of effect of COVID 19 pandemic on the utilization of maternal newborn child health and nutrition Services in Somali Region of Ethiopia. J Epidemiol Public Health. 2020;5(4):458–69. https://doi.org/10.26911/jepublichealth.2020.05.04.08.

Oluoch-Aridi J, Chelagat T, Nyikuri MM, Onyango J, Guzman D, Makanga C, et al. COVID-19 effect on access to maternal health services in Kenya. Front Glob Women’s Health. 2020;1:599267. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgwh.2020.599267.

Ombere SO. Access to maternal health services during the covid-19 pandemic: experiences of indigent mothers and health care providers in Kilifi County, Kenya. Front Sociology. 2021;6:613042. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2021.613042.

Pires PD, Macaringue C, Abdirazak A, Mucufo J, Mupueleque M, Siemens R, et al. COVID-19 pandemic impact on maternal and child health services access in Nampula, Mozambique: A Mixed Methods Research. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):860. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-104405/v1.

Semaan A, Banke-Thomas A, Amongin D, Babah O, Dioubate N, Amani KA, et al. We are not going to shut down, because we cannot postpone pregnancy’: a mixed-methods study of the provision of maternal healthcare in six referral maternity wards in four sub-Saharan African countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7:e008063.

Shakespeare C, Dube H, Moyo S, Ngwenya S. Resilience, and vulnerability of maternity services in Zimbabwe: a comparative analysis of the effect of COVID-19 and lockdown control measures on maternal and perinatal outcomes, a single-Centre cross-sectional study at Mpilo central hospital. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):416.

Shikuku DN, Nyaoke IK, Nyaga LK, Ameh CA. Early indirect impact of COVID-19 pandemic on utilisation and outcomes of reproductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health services in Kenya: a cross-sectional study. Afr J Reprod Health. 2021;25:6.

Tadesse E. Antenatal care service utilization of pregnant women attending antenatal care in public hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic period. Int J Women’s Health. 2020;12:1181–8. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S287534.

Temesgen K, Workie A, Dilnessa T, Getaneh E. The Impact of COVID-19 infection on maternal and reproductive health care services in governmental health institutions of Dessie town, North-East Ethiopia, 2020 G.C. J Women’s Health Care. 2021b;10:518. https://doi.org/10.35248/2167-0420.21.10.518.

World Health Organisation. Essential health services face continued disruption during COVID-19 pandemic. 2022 https://www.who.int/news/item/07-02-2022-essential-health-services-face-continued-disruption-during-covid-19-pandemic. Accessed 17 May 2022.

Zimmerman LA, Desta S, Karp C, Yihdego M, Seme A, Solomon Shiferaw S, et al. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on health facility delivery in Ethiopia; results from PMA Ethiopia’s longitudinal panel. PLOS. Global Public Health. 2021;1(10):e0000023. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000023.

Kenya Legal and Ethical Issues Network (KELIN) advisory note on ensuring a rights-based response to curb the spread of COVID-19. 2020. https://www.kelinkenya.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/letter2.pdf Accessed 04 November 2022.

Oluwasola TAO, Bello OO. COVID-19 and its implications for obstetrics and gynaecology practice in Africa. Pan African Medical Journal. 2021;38:15. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2021.38.15.25520.

Papageorghiou AT, Deruelle P, Gunier RB, Rauch S, García-May PK, Mhatre M, et al. Preeclampsia and COVID-19: results from the INTERCOVID prospective longitudinal study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225(3):289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2021.05.0142.

Eskenazi B, Rauch S, Iurlaro E, Gunier RB, Rego A, Gravett MG, et al. Diabetes mellitus, maternal adiposity, and insulin-dependent gestational diabetes are associated with COVID-19 in pregnancy: the INTERCOVID study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;227(1):74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2021.12.032.

COVIDSurg Collaborative, GlobalSurg Collaborative. SARS-CoV-2 infection and venous thromboembolism after surgery: an international prospective cohort study. Anaesthesia. 2022;77(1):28–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15563.

Chmielewska B, Barratt I, Townsend K, Kalafat E, van der Meulen J, Gurol-Urganci I, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Global Health. 2021;9(6):759–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00079-6.

Kotlar B, Gerson E, Petrillo S, Langer A, Tiemeier H. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal health: a scoping review. Reprod Health. 2021;18(1):10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01070-6.

Almeida M, Shrestha AD, Stojanac D, Miller LJ. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on women's mental health. Archives of women’s mental health. 2020;23(6):741–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-020-01092-2.

Demissie DB, Bitew ZW. Mental health effect of COVID-19 pandemic among women who are pregnant and/or lactating: a systematic review and meta-analysis. SAGE Open Medicine. 2021;9:20503121211026195. https://doi.org/10.1177/20503121211026195.

Okagbue HI, Adamu PI, Bishop SA, Oguntunde PE, Opanuga AA, Akhmetshin EM. Systematic review of prevalence of antepartum depression during the trimesters of pregnancy. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2019;7(9):1555–60. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2019.270.

Obilade TT. Ebola virus disease stigmatization; the role of societal attributes. Int Arch Med. 2015;8(14):1–19.

Strong AE, Schwartz DA. Effects of the West African Ebola Epidemic on Health Care of Pregnant Women: Stigmatization with and Without Infection. In: Pregnant in the Time of Ebola: Women and Their Children in the 2013–2015 West African Epidemic; 2018. p. 11–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97637-2_2.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. COVID-19: protecting people and society. 2020. https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/covid-19-protecting-people-and-societies-e5c9de1a/#snotesd4e3303. Accessed 30 June 2022.

Saxena, S., and Stone, M. Preparing public financial management systems to meet covid-19 challenges. 2020. PFM blog: Preparing Public Financial Management Systems to Meet Covid-19 Challenges (imf.org). Accessed 30 June 2022.

Langlois EV, McKenzie A, Schneider H, Mecaskey JW. Measures to strengthen primary health-care systems in low- and middle-income countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2020;98(11):781–91. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.20.252742.

The World Bank. Well-designed Primary Health Care Can Help Flatten the Curve during a Health Crisis like COVID-19. 2021. Well-designed Primary Health Care Can Help Flatten the Curve during Health Crises like COVID-19 (worldbank.org). Accessed 30 June 2022.

Nachega JB, Sam-Agudu NA, Siedner MJ, Rosenthal PJ, Mellors JW, Zumla A, et al. Prioritizing pregnant women for coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination in African countries. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;75(8):1462–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciac362.

Asamani JA, Ismaila H, Okoroafor SC, Frimpong KA, Oduro-Mensah E, Chebere M, et al. Cost analysis of health workforce investments for COVID-19 response in Ghana. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7(Suppl 1):e008941. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2022-008941.

Ameyaw EED, Ahikorah BO, Seidu A, Njue C. Impact of COVID-19 on maternal healthcare in Africa and the way forward. Archives of Public Health. 2021;79:223.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all global alliance of nurses and midwives’ members especially Dr. Una V. Reid, Stembile Mugore, Lydia Fraser who proofread this paper.

Availability of data and materials statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Funding

No external sources of funding for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design were done by E.K.S., M.O., E.A. E.K.S, M.O., M.B. D.A., O.E., E.A. wrote the main manuscript text. Analysis and interpretation by E.K.S., M.B. M.O., E.A. Critical revision by D.A., O.E., M.D., R.W., E.A. M.B. M. O,E.K.S. E.K.S. M.O. M.B. prepared fig. 1, tables 1–3. E.K.S. M.B., M.O., D.A., O.E., M.D., R.W. E.A. approved the final version for publication. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

E.K.S.; B. Sc (Hons), GradCert.HAT, RGN.

M.O.; PhD, M.Sc., B. Sc, RM, RGN.

O.E.; PhD, M.Sc., B. Sc.

D.A.; PhD, M. A, B. Sc.

E.A.; PhD, M. Phil, B. Sc, RGN, RM, PN, FSTI, FWACNM, FGCNM.

R.W.; MSN, PMHP, FNP, BSN, RN.

M.D.; PhD, M.Sc., B.Sc., RM, RGN, RNMH.

M.B.; PhD, MPH, B. Sc, RN, CNM, FACNM.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

No approval sought for the study from Ethics Committee or an Institutional Review Board. Hence consent to participate is not applicable to this study.

Consent for publication

No consent needed as the study is a review.

Competing interests

The authors declare no completing interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Senkyire, E.K., Ewetan, O., Azuh, D. et al. An integrative literature review on the impact of COVID-19 on maternal and child health in Africa. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 23, 6 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-05339-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-05339-x