Abstract

Background

The perinatal period is a time of increased vulnerability to mental health problems, however, only a small proportion of women seek help. Poor mental health literacy (MHL) is a major barrier to seeking help for mental health problems. This study aimed to collect the existing evidence of MHL associated with perinatal mental health problems (PMHP) among perinatal women and the public. This review analysed which tools were used to assess perinatal MHL as well as the findings concerning individual components of perinatal MHL.

Methods

Four electronic databases (PubMed, PsycINFO, Web of Science, and CINAHL) were analysed from their inception until September 1, 2020. Not only quantitative studies reporting on components of MHL (knowledge, attitudes, and help-seeking), but also studies reporting overall levels of MHL relating to PMHP were taken into account. Two independent reviewers were involved in the screening and extraction process and data were analysed descriptively.

Results

Thirty-eight of the 13,676 retrieved articles satisfied the inclusion criteria. The majority of selected studies examined MHL related to PMHP in perinatal women (N = 28). The most frequently examined component of MHL in the selected data set was help-seeking. A lack of uniformity in assessing MHL components was found. The most common focus of these studies was postpartum depression. It was found that the ability to recognize PMHP and to identify relevant symptoms was lacking among both perinatal women and the public. Perinatal women had low intentions of seeking help for PMHP and preferred seeking help from informal sources while reporting a variety of structural and personal barriers to seeking help. Stigmatizing attitudes associated with PMHP were found among the public.

Conclusions

There is a need for educational campaigns and interventions to improve perinatal MHL in perinatal women and the public as a whole.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pregnancy and early motherhood often signal a time of joy and excitement but also a time of massive change and challenges. During this period, women are especially vulnerable to developing perinatal mental health problems (PMHP) (i.e., mental health problems that manifest during pregnancy and up to 1 year after delivery) [1, 2]. The most prevalent mental disorders are perinatal depression and anxiety disorders. Globally, approximately 17% of women suffer from postpartum depression (PPD), which can be distinguished from temporary postpartum blues, a milder and shorter form of depressive symptoms [3, 4]. Less prevalent are bipolar disorders and postpartum psychosis with postpartum psychosis occurring in 0.1–0.2% of childbearing women [5]. All PMHP represent a public health concern due to their impact on the health of mothers and their infants. Negative associations between PMHP and behavioural and cognitive development of children up to adolescence highlight the importance of adequate and timely treatment [6, 7]. Often, however, PMHP remain undiagnosed and subsequently untreated. In the case of PPD, only 6.3% of women receive adequate treatment [8]. Unfortunately, even when perinatal health services are available, women in the perinatal period seek less help compared to women in other life periods [9, 10]. Evidence suggests that one factor influencing help-seeking rates is mental health literacy [11]. As such, poor perinatal mental health literacy might play an important role in the low healthcare utilization of perinatal women [12].

Mental health literacy (MHL) was initially defined as “[…] knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders which aid recognition, management or prevention” [13]. A more recent operationalization of the MHL concept by Kutcher et al. additionally includes the sub-components attitudes and help-seeking [14]. This definition does not only add the concept of stigma but also the concept of help-seeking efficacy to the definition of MHL. Low MHL has been identified as one of the reasons for the limited use of mental health services [14]. However, not only help-seeking efficacy but also help-seeking attitudes have been shown to be predictors of help-seeking intention and behaviour. To emphasize the concept of help-seeking attitudes as suggested by Chao et al. [15] we expanded the concept of MHL beyond the definition of Kutcher et al. to capture a wide range of help-seeking factors (e.g., intentions, barriers) for the purpose of this review.

The aim of this review was to summarize research on a broad range of perinatal MHL components in both perinatal women and the public. Inaccurate notions of mental health in perinatal women can impede early detection and treatment of their mental health problems. Therefore, perinatal MHL is an important factor influencing the recognition, diagnosis, and treatment of PMHP. For instance, Dennis & Lee [16], who summarized qualitative studies on postpartum depression help-seeking barriers, found lack of knowledge and the acceptance of myths to be important help-seeking barriers impeding mothers to recognize the emergence of depression. Moreover, help-seeking was shown to be influenced by stigma, shame, and the fear of being labelled mentally ill [16]. However, not only the view of perinatal women but also the public’s view regarding mental health problems in the perinatal period is an important factor to understand the decision-making, help-seeking, and healthcare utilization of women in the perinatal period [17]. To deliver effective MHL interventions it is important to consider the context that influences the impact of the interventions, including the public’s view on PMHP. Several studies suggest that the general population has poor knowledge about PPD [18, 19], which could potentially discourage women from seeking professional help.

According to Kutcher et al. [14], effective MHL interventions should improve the knowledge and help-seeking aspect of MHL and reduce stigma. As most studies that examined perinatal MHL in perinatal women and the public focused on individual aspects of MHL (e.g., knowledge component) [17, 20], the rationale for conducting this review was to synthesize findings on all aspects of perinatal MHL (knowledge, attitudes, and help-seeking). Identifying the components of MHL that are especially prone to impede help-seeking for PMHP could inform MHL campaigns and interventions. Therefore, it is important to conduct research on all components of MHL regarding PMHP in perinatal women and the public.

We summarized research on perinatal MHL expanding the concepts of Jorm et al. [13] and Kutcher et al. [14]. Our purpose was (1) to identify tools to measure PMHL components and (2) to summarize the existing evidence on MHL among perinatal women and the public with a focus on MHL components knowledge, attitudes, and help-seeking.

Methods

This review followed the PRISMA reporting standards [21]. The PRISMA checklist is available in Additional file 1. The protocol is available at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42020208450. We used the PEO (Population, Exposure, Outcomes) framework to specify our research questions. P: perinatal women or the public. E: PMHP (e.g., postpartum depression, prenatal depression) O: MHL components: knowledge, attitudes, help-seeking, and overall levels of MHL.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Published studies in German or English were eligible for inclusion. Databases were searched from their year of inception until September 1, 2020, without geographic restriction. We included all studies assessing MHL of PMHP among perinatal women and the public. We excluded studies investigating concepts (knowledge, attitudes, help-seeking) among professionals (e.g., midwives, general practitioners). Only outcomes related to maternal - not paternal - mental health in the perinatal period were included. We included quantitative studies (e.g., cross-sectional studies, prospective cohort studies). For studies other than cross-sectional studies, only baseline results were included. Qualitative studies, reviews, and meta-analyses were excluded. If qualitative studies used open-end questions and presented their results in a quantitative manner (e.g., percentages), studies were included.

Search strategy for identification of studies

On September 1, 2020, the databases PubMed, PsycINFO, Web of Science, and CINAHL were systematically searched. We performed a Boolean search using the concepts (1) MHL, (2) perinatal period, and (3) mental illness. We used the following keywords: (“Mental health literacy” OR “Health literacy” OR literacy OR knowledge OR attitude* OR belief* OR stigma* OR “help-seek*”) AND (prenatal OR antenatal OR pregnancy OR “before birth” OR postnatal OR postpartum OR “after birth” OR peripartum OR perinatal) AND (“mental health” OR “mental illness” OR “mental disorder” OR “psychiatric disorder” OR depression OR anxiety OR “baby blues” OR psychosis OR “bipolar disorder”) to search titles, abstracts, keywords and MeSh terms (see Additional file 2). Additional studies were identified through a manual search of the bibliographic references of the included full texts.

Study selection and critical appraisal

We imported all identified references to the literature database EndNote and removed duplicate records of the same reports. Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts and subsequently screened all retrieved full texts for inclusion and exclusion criteria. The methodological quality of the included studies was independently assessed by both researchers using the following tools: (1) Included Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were assessed by the Cochrane Collaboration’s Tool for RCTs [22]; (2) Cross-sectional studies were assessed by the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) [23]; (3) Non-randomized studies (all cohort studies, case-control studies) were assessed by the Qualitative Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies (QATSQ) [24] (see Additional file 3). Any disagreements between the two researchers were resolved through discussion and consensus.

Data extraction and synthesis

Two researchers extracted the data according to a developed data extraction form. To extract numerical data from plots, we used WebPlotDigitizer [25]. The extracted data included study information (e.g., authors, publication year); study characteristics (e.g., study design, sampling method); participant characteristics (e.g., sex, age) and outcomes: (1) tools to measure perinatal MHL components and (2) perinatal MHL components and levels of perinatal MHL. The extracted MHL components extended the definitions of MHL by Jorm et al. [13] and Kutcher et al. [14] and included: (a) knowledge of PMHP (recognition, symptoms, causes, first aid, intervention, and preventive measures), (b) attitudes towards PMHP (stigmatizing attitudes and beliefs), (c) help-seeking attitudes (preferred treatment, preferred source of help, barriers and facilitators) & intentions. Data were descriptively analysed.

Results

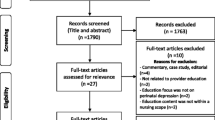

Of the 13,608 references retrieved from the databases and the 68 references retrieved from the reference sections of included studies, we identified 78 full texts of potentially eligible articles. After full-text screening and critical appraisal, 38 eligible studies remained and were included (see Fig.1).

Characteristics of studies

Study characteristics and components of perinatal MHL are shown in Table 1.

The majority of studies were cross-sectional studies using convenience sampling. Participants in 28 studies (73.7%) were women in the perinatal period who were either pregnant or had recently given birth. Seven of these studies only included women at risk of perinatal depression, women who had or were currently experiencing PPD, or women with symptoms of distress. Next to the tools used to measure PMHL, results are presented within the main categories of MHL: knowledge, attitudes, and help-seeking. Results on overall levels of PMHL can be found in Additional file 4.

Tools to measure perinatal MHL components

The most commonly used tools to measure the knowledge component of perinatal MHL were vignette-based measures (23.1%), measures drawn from the Australian Perinatal Depression Monitor [18], and study-specific measures (e.g., semi-structured interviews, true/false questions). Attitudes and beliefs towards PMHP were most commonly examined by the Attitudes about Postpartum Depression Questionnaire [30] and the Stigma subscale of the Portuguese version of the Inventory of Attitudes Toward Seeking Mental Health Services [61]. Help-seeking attitudes (preferred treatment, preferred source of help, barriers, and facilitators) were most commonly assessed by showing participants a list of items and asking them to select all that applied. Help-seeking intentions were most commonly captured by single questions (e.g., ‘would you seek help if you had symptoms of postnatal depression or anxiety?’). See Additional file 5 for details.

Knowledge of PMHP

Results on the knowledge component of perinatal MHL are presented in Table 2.

Recognition

The ability to recognize PMHP was reported in six studies. One study conducted in an Australian community sample reported that the majority of participants were able to recognize PPD, whereas two studies among perinatal women reported that the majority of participants were unable to recognize PPD in case vignettes. Three other studies among the public assessed recognition of PMHP by the percentage of spontaneous responses to the question ‘what do you consider to be the major health problems which may be experienced during pregnancy/in the first year?’ [18, 55] and the question ‘have you heard about PPD?’ [30]. Depression was the most commonly cited potential health problem of women in the postpartum period [18, 55].

Symptoms

All studies that assessed knowledge about symptoms of PMHP included participants from the public as a whole. Only a small number of participants correctly identified typical symptoms of PPD (30.2–62.2%). The percentage of women reporting difficulties in the mother-child relationship (e.g., lack of bonding, harm to the baby) as a symptom of PPD varied heavily between 5 and 77.1%. Concerning the baby blues, in one study, approximately 30% of participants correctly stated that the baby blues would not extend longer than 2 weeks [19]. In another study, symptoms of postnatal anxiety were correctly identified by less than 20%. More than 40% of those surveyed were not able to name one symptom [55].

Causes

Hormonal/biological changes were a frequently cited cause of PPD and perinatal depression among perinatal women and the public. Among the public, hormonal/biological changes were the most commonly cited cause of PPD. Unpreparedness for or not coping with parenthood was another frequently mentioned cause of PPD among the public [18, 55, 56]. Lack of social support was another perceived cause of PPD and perinatal depression among perinatal women and the public, with values ranging from 8.5 to 75%. However, in contrast to the public, lack of social support was the most frequently reported cause of PPD and perinatal depression among perinatal women. Other perceived causes of PPD and perinatal depression included: lack of sleep and exhaustion, depression and anxiety during pregnancy, stress, and genetic tendencies.

Interventions

Regarding PPD, the public most often considered professional help (e.g., counselling, psychotherapy) to be a helpful treatment. Partner/family support, on the other hand, was considered to be helpful by a small proportion of participants from the public. In contrast, in one study, a large number (93%) of perinatal women reported that partner support was helpful for PPD. Less than 30% of participants from the general public considered antidepressants to be an appropriate intervention [18, 55]. Among perinatal women, antidepressants were cited as an appropriate intervention for treating PPD by 54% of participants [32]. The same study also indicated that 78% of participants considered vitamins and minerals helpful for treating PPD. Regarding prenatal depression, partner assistance was considered helpful by almost all participants in one study (96%), followed by vitamins and minerals (86%) [32].

Stigmatising attitudes and beliefs regarding PMHP

Results on the stigmatising attitudes and beliefs component of perinatal MHL are presented in Table 3.

The most commonly reported aspects of negative or trivializing beliefs reported among the public were: ‘it is normal to have PPD’ and that ‘women know by nature how to look after a baby’. Two studies indicated that participants most often agreed with the attitude ‘it is normal to be depressed during pregnancy’ [18, 55]. Similarly, half of an Australian community sample viewed being depressed during pregnancy as ‘a normal part of having a baby’ [18]. In a third study, 11.4% of the participants agreed with the statement ‘women with postpartum depression cannot be good mothers’ and 12.1% agreed with ‘women have postpartum depression because they have unrealistic expectations about caring for a baby’. Furthermore, 11.6% of the participants disagreed with the statement ‘postpartum depression is not a sign of weakness’ [30].

Help-seeking for PMHP

The large majority of studies (N = 34) reported at least one aspect of help-seeking for PMHP. Results are presented in Tables 4 and 5.

Although in some studies, a high proportion of women reported a need for treatment or were interested in professional health services during the perinatal period, the percentage of women who intended to seek help for PMHP was generally below 40%. However, in one study approximately three-quarters of women stated that they would seek professional help if they experienced symptoms of perinatal depression and anxiety [52].

Preferred source of help

Whereas perinatal women preferred informal sources of help such as family or friends in most studies, the public commonly preferred formal sources of help such as GPs. Although women preferred informal sources of help from family and friends, men would rather recommend formal sources of help [18, 55]. The most commonly preferred formal source of help was medical health professionals (e.g., GPs), followed by mental health professionals. In one study, gynaecologists and psychiatrists were both equally preferred [59]. The remaining studies did not clearly differentiate between medical professionals and mental health professionals [28, 39].

Preferred treatment

The most frequently reported preferred treatment type among perinatal women and the public was counselling/therapy. Treatment preferences differed between pregnant, breastfeeding, and non-breastfeeding women [52]. Pregnant women preferred individual counselling, breastfeeding women meditation, yoga or exercise and non-breastfeeding women preferred combined counselling and medication. In one study, the most commonly preferred treatment type (83.6%) was ‘Wait and get over it naturally’ [53].

Help-seeking barriers and facilitators

Twenty studies assessed barriers and/or facilitators to help-seeking for PMHP in perinatal women and one among parents [58].

Barriers

Structural, attitudinal, and knowledge-related barriers were reported (see Table 5). Among structural barriers, two main categories emerged. (1) cost of treatment and (2) inability to attend appointments due to: time constraints, logistics/transportation, childcare, distance/geographic mismatch, and unavailability of providers/resources. The most commonly reported attitudinal barriers were associated with stigma and shame. Approximately 50% of women reported that fear, shame, and embarrassment of their feelings prevented them from seeking help [28]. Moreover, shame proneness predicted negative attitudes towards help-seeking [34]. The anticipated opinion of other people (e.g., ‘I didn’t think others would understand’ or ‘being afraid of what my family and/or friends might think of me’) and the attitude towards help-seeking (‘wanting to manage symptoms on their own’) were other barriers frequently mentioned by women. The knowledge barriers most frequently mentioned were not knowing where to seek help/who to contact and not knowing what the best treatment option might be.

Facilitators

The majority of studies assessed facilitators that predicted help-seeking intentions or behaviour. Social support was the facilitator most commonly reported. Six studies determined high support and encouragement by family/partners as a facilitator to help-seeking or symptom disclosure; however, one study found that less social support increased treatment uptake [52]. Severity of illness was another frequently mentioned facilitator. Although higher symptom severity facilitated help-seeking in most studies, one study found that women with more severe depressive symptoms reported more barriers to help-seeking [33]. Five studies found that the relationship to and confidence in mental health professionals facilitated help-seeking. For instance, in three studies encouragement by healthcare professionals was found to be a help-seeking facilitator. Past experiences of mental illness or treatment was another commonly expressed facilitator to help-seeking in five studies. For instance, women sought professional assistance more frequently if they had a history of mental health problems and treatment [35]. The attitude towards diagnosis and treatment was another facilitator. For instance, the perceived need for treatment was found to be a help-seeking facilitator [27, 43]. Moreover, two other studies found that ‘the belief that symptoms would last a long time’ predicted help-seeking behaviour [49] and that more positive attitudes towards seeking professional psychological help increased intentions to seek help [45].

Discussion

The purpose of this study was (1) to identify tools used to measure perinatal MHL components and (2) to summarize the existing evidence on perinatal MHL with a special focus on knowledge, attitudes, and help-seeking. This review identified several aspects of perinatal MHL, which should be targeted in interventions and campaigns.

A large heterogeneity of assessment of MHL components and sub-components was found; therefore, making it difficult to compare results. For instance, some studies reported percentages of correct responses, whereas others reported the endorsement of participants with specific statements. Several studies did not provide evidence for the psychometric validity of measures or developed their own study measures. Recognition of symptoms, for instance, was assessed in several different ways, with only half of the studies using case vignettes, which is in line with the operationalization of recognition of mental disorder as the ability to identify and name a mental disorder based on a written case vignette [67]. Our results are in accordance with the research of Singh et al. who found a lack of uniformity in assessing MHL components among adolescents [68]. In the case of symptom recognition, future research should use a standardized set of vignettes. Likewise, instead of using study-specific lists of statements to assess treatment barriers for PMHP, standardized measures such as the Perceived Barriers to Psychological Treatment (PBPT) scale could be adapted and used in future research [69]. Regarding levels of perinatal MHL, a tool to measure postpartum depression literacy (The postpartum depression literacy scale, PoDLiS) within the mental health literacy framework has been developed recently [47]. Future research should employ valid and reliable measures to assess all components of perinatal MHL literacy.

Less heterogeneity was found with regard to the specific PMHP studied. Almost all studies focused on perinatal MHL in relation to perinatal depression or PPD specifically. However, incidences of other PMHP such as perinatal anxiety are high and merit clinical attention similar to that given to perinatal depression [70]. Future research assessing MHL in the context of other PMHP is warranted.

Findings on the knowledge component of perinatal MHL suggest that women and the public have a partly fragmented and differing understanding of PMHP. Although misconceptions relating to symptoms, causes, and treatment options for PMHP were found in both, perinatal women and the public, a few differences were observed. Perinatal women most commonly considered lack of social support as a cause for PMHP; however, the public most commonly attributed postnatal depression to biological factors. Importantly, biological factors are not among the most important risk factors as identified by research: antenatal depression and anxiety, major life events, lack of (partner) support, and depression history [71,72,73,74]. This misconception and possible confusion of PPD with the baby blues may explain why some stereotypes such as ‘it is normal to have PPD’ exist among the public. Public educational campaigns highlighting the significance of PMHP could counteract misconceptions and trivializing notions. This seems especially important considering that higher public knowledge of PMHP is associated with higher intention to recommend help-seeking [31] and might therefore influence help-seeking behaviour of perinatal women. Perinatal women most commonly reported social support as a helpful intervention and preferred informal sources of treatment. This is disconcerting because PMHP often require professional treatment [75]. Therefore, it is important to educate women that –although social factors are among the causes of PMHP– informal sources of help (such as support from the partner) may not be sufficient to effectively treat PMHP. It is important to highlight the importance of professional help and to reduce the barriers associated with formal help-seeking.

Consistent with previous research, stigma and shame were the most prevalent barriers to help-seeking in perinatal women [16]. By discussing PMHP with perinatal women, providers (e.g., gynaecologists, midwives, and obstetricians) could improve knowledge and reduce stigma and shame. Innovative treatment options such as internet-based interventions could be used to circumvent both structural and stigma-related barriers. For instance, internet-based interventions including information and cognitive behavioural strategies were shown to influence levels of depression stigma and attitudes towards PPD [63, 76, 77].

Our finding that social facilitators (such as social support and encouragement, relationships with providers, and attitudes towards mental illness) are the most commonly reported reasons to seek help has also been reported elsewhere [78]. To strengthen social support, interventions should be developed that provide strategies for reinforcing and mobilizing women’s social networks in the perinatal period; e.g. by developing a post-birth support plan [51]. This seems particularly important as the social network often tends to recommend formal rather than informal treatment and therefore may serve as an important gateway for the transition from informal to formal treatment.

Practical implications

There is a need for campaigns and interventions to raise perinatal MHL among both, perinatal women and the public.

First, perinatal women and the public should be educated about the symptoms, risk factors, and treatment options of PMHP to increase problem recognition and service selection. Common misconceptions – such as the high attribution of PPD to biological factors and the underestimation of psychosocial causes – should be addressed. Given the important role of partners in encouraging women to seek help, it seems essential that the social network of women can recognize PMHP and understands the important role of support and encouragement as a facilitator to perinatal help-seeking. Consistent with the recommendations of Poreddi et al. [79], this review highlights the importance of educational campaigns, which aim to improve perinatal MHL by addressing prejudices and negative stereotypes associated with PPD [79]. Importantly, campaigns and interventions should not solely focus on PPD, but also raise awareness about less understood PMHP such as prenatal depression and perinatal anxiety.

Additionally, perinatal women should receive information on relevant providers and treatment options to decrease knowledge barriers to help-seeking and subsequently facilitate service selection. Ideally, healthcare providers who work directly with pregnant women and new parents (such as midwives, gynaecologists, paediatricians, and GPs) should discuss PMHP, screen for PMHP, discuss treatment options, and refer patients for treatment. However, medical professionals often lack resources or knowledge to address PMHP [80]. In addition to raising the awareness of health care professionals with the goal of increasing provider MHL and thus screening rates [81], more comprehensive approaches are needed. Given that the smartphone is the most commonly used device with internet access among perinatal women [82], developing and evaluating evidence-based content for smartphone use could be one approach to improve perinatal MHL among women and the public. Such an approach is currently evaluated (www.smart-moms.de).

Second, campaigns and interventions should focus on stigmatizing attitudes. Stigma and shame are not only a substantial barrier to help-seeking for PMHP [16], but also influence the public’s intention of recommending professional help for PMHP [31]. Given that social support and partner encouragement are important help-seeking facilitators, campaigns and interventions addressing stigmatizing attitudes towards PMHP among the public have the potential to increase the essential support from the social network and subsequently increase help-seeking rates among perinatal women.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this study was the first systematic review to summarize findings on perinatal MHL. Moreover, this review incorporated several aspects of perinatal MHL and expanded the concept by Kutcher et al. [14] to capture a wide range of help-seeking factors (e.g., intentions, barriers). The quality of studies was appraised by using different tools recommended for use in systematic reviews. A limitation that should be mentioned is that we limited our search to studies in English and German and did not include any source of Grey literature. Therefore, this review might be subject to publication bias. Moreover, due to the substantial number of outcomes related to perinatal MHL and the heterogeneity of tools used in the studies, findings should be interpreted with caution. It should be noted that most of the included studies were conducted in Western countries. Since the experience of shame and stigma is often culturally or socially determined [83, 84], our results may not be generalizable to non-Western cultures. As PMHP also affect men [85], future research on MHL in relation to paternal PMHP, and any interactions or associations between maternal and paternal PMHP, is warranted. Additionally, future reviews with a focus on qualitative studies would be highly valuable to shed more light on the individual experiences of perinatal women and the public as a whole.

Conclusions

In summary, a multidisciplinary approach that supports perinatal health care professionals in their role as gatekeepers to perinatal mental help treatment and also increases the accessibility of sensitive information about PMHP for perinatal women and the public is needed. Future research should investigate the effects of perinatal MHL campaigns and interventions on actual help-seeking behaviour.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Abbreviations

- MHL:

-

Mental health literacy

- PMHP:

-

perinatal mental health problems

- PPD:

-

postpartum depression

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

References

O'Hara MW, Wisner KL. Perinatal mental illness: definition, description and aetiology. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;28(1):3–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2013.09.002.

Smith MV, Shao L, Howell H, Lin H, Yonkers KA. Perinatal depression and birth outcomes in a healthy start project. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15(3):401–9.

Hirst KP, Moutier CY. Postpartum major depression. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(8):926–33.

Wang Z, Liu J, Shuai H, Cai Z, Fu X, Liu Y, Xiao X, Zhang W, Krabbendam E, Liu S. Mapping global prevalence of depression among postpartum women. Transl Psychiatry. 2021; 11(1):1–13.

Sit D, Rothschild AJ, Wisner KL. A review of postpartum psychosis. J Women's Health. 2006;15(4):352–68. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2006.15.352.

Murray L, Fearon P, Cooper P. Postnatal depression, mother-infant interactions, and child development: prospects for screening and treatment. In: Milgrom J, Gemmill AW, editors. Identifying perinatal depression and anxiety: evidence-based practice in screening, psychosocial assessment, and management: Wiley Blackwell; 2005. p. 139–64.

Netsi E, Pearson R, Murray L, Cooper P, Craske M, Stein A. Association of persistent and severe postnatal depression with child outcomes. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:247–53.

Cox EQ, Sowa NA, Meltzer-Brody SE, Gaynes BN. The perinatal depression treatment cascade: baby steps toward improving outcomes. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2016;77(9):1189–200. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.15r10174.

Vesga-Lopez O, Blanco C, Keyes K, Olfson M, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Psychiatric disorders in pregnant and postpartum women in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(7):805–15.

Sorsa MA, Kylmä J, Bondas TE. Contemplating help-seeking in perinatal psychological distress—a Meta-ethnography. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5226.

Cheng HL, Wang C, McDermott RC, Kridel M, Rislin JL. Self-stigma, mental health literacy, and attitudes toward seeking psychological help. Journal of Counseling & Development. 2018;96(1):64–74.

Muzik M, Borovska S. Perinatal depression. Implications for child mental health. Ment health. Fam Med. 2010;7(4):239–47.

Jorm AF, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Christensen H, Rodgers B, Pollitt P. "mental health literacy": a survey of the public's ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Med J Aust. 1997;166(4):182–6. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb140071.x.

Kutcher S, Wei Y, Coniglio C. Mental health literacy: past, present, and future. Can J Psychiatr. 2016;61(3):154–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743715616609.

Chao H-J, Lien Y-J, Kao Y-C, Tasi I-C, Lin H-S, Lien Y-Y. Mental health literacy in healthcare students: an expansion of the mental health literacy scale. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(3):948.

Dennis CL, Chung-Lee L. Postpartum depression help-seeking barriers and maternal treatment preferences: a qualitative systematic review. Birth. 2006;33(4):323–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-536X.2006.00130.x.

Kingston DE, McDonald S, Austin MP, Hegadoren K, Lasiuk G, Tough S. The Public's views of mental health in pregnant and postpartum women: a population-based study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:84. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-14-84.

Highet NJ, Gemmill AW, Milgrom J. Depression in the perinatal period: awareness, attitudes and knowledge in the Australian population. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;45(3):223–31. https://doi.org/10.3109/00048674.2010.547842.

Sealy PA, Fraser J, Simpson JP, Evans M, Hartford A. Community awareness of postpartum depression. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2009;38(2):121–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6909.2009.01001.x.

Buist A, Speelman C, Hayes B, Reay R, Milgrom J, Meyer D, et al. Impact of education on women with perinatal depression. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;28(1):49–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/01674820601143187.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d5928.

Wells GA, Shea BO, Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M & Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2000. Available from: URL: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.htm. Accessed Oct 15 2020.

Quality Assessment Tool For Quantitative Studies [https://merst.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/quality-assessment-tool_2010.pdf]. Accessed Oct 15 2020.

Rohatgi A. WebPlotDigitizer Version: 4.1. Austin. 2018.

Ayres A, Chen R, Mackle T, Ballard E, Patterson S, Bruxner G, et al. Engagement with perinatal mental health services: a cross-sectional questionnaire survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):170. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2320-9.

Azale T, Fekadu A, Hanlon C. Treatment gap and help-seeking for postpartum depression in a rural African setting. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:196. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-0892-8.

Barrera AZ, Nichols AD. Depression help-seeking attitudes and behaviors among an internet-based sample of Spanish-speaking perinatal women. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2015;37(3):148–53.

Bina R. Seeking help for postpartum depression in the Israeli Jewish orthodox community: factors associated with use of professional and informal help. Women Health. 2014;54(5):455–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2014.897675.

Branquinho M, Canavarro MC, Fonseca A. Knowledge and attitudes about postpartum depression in the Portuguese general population. Midwifery. 2019;77:86–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2019.06.016.

Branquinho M, Canavarro MC, Fonseca A. Postpartum depression in the Portuguese population: the role of knowledge, attitudes and help-seeking propensity in intention to recommend professional help-seeking. Community Ment Health J. 2020;56(8):1436–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-020-00587-7.

Buist A, Bilszta J, Barnett B, Milgrom J, Ericksen J, Condon J, et al. Recognition and management of perinatal depression in general practice: a survey of GPs and postnatal women. Aust Fam Physician. 2005;34(9):787–90.

Da Costa D, Zelkowitz P, Nguyen T-V, Deville-Stoetzel J-B. Mental health help-seeking patterns and perceived barriers for care among nulliparous pregnant women. Arch Women's Mental Health. 2018;21(6):757–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-018-0864-8.

Dunford E, Granger C. Maternal guilt and shame: relationship to postnatal depression and attitudes towards help-seeking. J Child Fam Stud. 2017;26(6):1692–701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0690-z.

Fonseca A, Gorayeb R, Canavarro MC. Women′s help-seeking behaviours for depressive symptoms during the perinatal period: socio-demographic and clinical correlates and perceived barriers to seeking professional help. Midwifery. 2015;31(12):1177–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2015.09.002.

Fonseca A, Canavarro MC. Women's intentions of informal and formal help-seeking for mental health problems during the perinatal period: the role of perceived encouragement from the partner. Midwifery. 2017;50:78–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2017.04.001.

Fonseca A, Moura-Ramos M, Canavarro MC. Attachment and mental help-seeking in the perinatal period: the role of stigma. Community Ment Health J. 2018;54(1):92–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-017-0138-3.

Ford E, Roomi H, Hugh H, van Marwijk H. Understanding barriers to women seeking and receiving help for perinatal mental health problems in UK general practice: development of a questionnaire. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2019;20:e156. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1463423619000902.

Goodman JH. Women's attitudes, preferences, and perceived barriers to treatment for perinatal depression. Birth. 2009;36(1):60–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-536X.2008.00296.x.

Goodman SH, Dimidjian S, Williams KG. Pregnant African American women's attitudes toward perinatal depression prevention. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2013;19(1):50–7. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030565.

Henshaw E, Sabourin B, Warning M. Treatment-seeking behaviors and attitudes survey among women at risk for perinatal depression or anxiety. J Obstetr Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2013;42(2):168–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/1552-6909.12014.

Holt C, Milgrom J, Gemmill A. Improving help-seeking for postnatal depression and anxiety: a cluster randomised controlled trial of motivational interviewing. Arch Women's Mental Health. 2017;20(6):791–801. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-017-0767-0.

Kim JJ, La Porte LM, Corcoran M, Magasi S, Batza J, Silver RK. Barriers to mental health treatment among obstetric patients at risk for depression. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010;202(3):312. e311–312. e315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2010.01.004.

Kingston D, McDonald S, Tough S, Austin MP, Hegadoren K, Lasiuk G. Public views of acceptability of perinatal mental health screening and treatment preference: a population based survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:67. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-14-67.

Logsdon MC, Rn DM, Phd JAM, Capps J, Masterson KM. Intention to seek depression treatment in Latina immigrant mothers. Issues Mental Health Nurs. 2018;39(11):962–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2018.1479905.

Logsdon MC, Myers J, Rushton J, Gregg JL, Josephson AM, Davis DW, et al. Efficacy of an internet-based depression intervention to improve rates of treatment in adolescent mothers. Arch Womens Mental Health. 2018;21(3):273–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-017-0804-z.

Mirsalimi F, Ghofranipour F, Noroozi A, Montazeri A. The postpartum depression literacy scale (PoDLiS): development and psychometric properties. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2705-9.

O'Mahen HA, Flynn HA. Preferences and perceived barriers to treatment for depression during the perinatal period. J Women's Health (Larchmt). 2008;17(8):1301–9. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2007.0631.

O'Mahen HA, Flynn HA, Chermack S, Marcus S. Illness perceptions associated with perinatal depression treatment use. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2009;12(6):447–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-009-0078-1.

Patel SR, Wisner KL. Decision making for depression treatment during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Depression Anxiety. 2011;28(7):589–95. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20844.

Prevatt BS, Desmarais SL. Facilitators and barriers to disclosure of postpartum mood disorder symptoms to a healthcare provider. Matern Child Health J. 2018;22(1):120–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-017-2361-5.

Ride J, Lancsar E. Women's preferences for treatment of perinatal depression and anxiety: a discrete choice experiment. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0156629. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0156629.

Sleath B, West S, Tudor G, Perreira K, King V, Morrissey J. Ethnicity and depression treatment preferences of pregnant women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;26(2):135–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443610400023130A.

Small R, Brown S, Lumley J, Astbury J. Missing voices: what women say and do about depression after childbirth. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 1994;12(2):89–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646839408408872.

Smith T, Gemmill AW, Milgrom J. Perinatal anxiety and depression: awareness and attitudes in Australia. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2019;65(5):378–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764019852656.

Thorsteinsson EB, Loi NM, Moulynox AL. Mental health literacy of depression and postnatal depression: a community sample. Open J Depression. 2014;03(3):101–11. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojd.2014.33014.

Thorsteinsson EB, Loi NM, Farr K. Changes in stigma and help-seeking in relation to postpartum depression: non-clinical parenting intervention sample. PeerJ. 2018;6:e5893 https://peerj.com/articles/5893/.

Wenze SJ, Battle CL. Perinatal mental health treatment needs, preferences, and barriers in parents of multiples. J Psychiatr Pract. 2018;24(3):158–68. https://doi.org/10.1097/pra.0000000000000299.

Zittel-Palamara K, Rockmaker JR, Schwabel KM, Weinstein WL, Thompson SJ. Desired assistance versus care received for postpartum depression: access to care differences by race. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2008;11(2):81–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-008-0001-1.

Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150(6):782–6. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.150.6.782.

Fonseca A, Silva S, Canavarro MC. Características psicométricas do Inventário de Atitudes face à Procura de Serviços de Saúde Mental: Estudo em mulheres no período perinatal. Psychologica. 2017;60(2):65–81 https://doi.org/10.14195/1647-8606.

Mackenzie CS, Knox VJ, Gekoski WL, Macaulay HL. An adaptation and extension of the attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help scale 1. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2004;34(11):2410–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb01984.x.

Griffiths KM, Christensen H, Jorm AF, Evans K, Groves C. Effect of web-based depression literacy and cognitive–behavioural therapy interventions on stigmatising attitudes to depression: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185(4):342–9. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.185.4.342.

Wilson CJ, Deane FP, Ciarrochi JV, Rickwood D. Measuring help seeking intentions: properties of the general help seeking questionnaire. Can J Couns. 2005;39(1):15–28.

Gerend MA, Lee SC, Shepherd JE. Predictors of human papillomavirus vaccination acceptability among underserved women. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34(7):468–71. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.olq.0000245915.38315.bd.

Orth U, Berking M, Burkhardt S. Self-conscious emotions and depression: rumination explains why shame but not guilt is maladaptive. Personal Soc Psychol Bull. 2006;32(12):1608–19.

Wang J, Lai D. The relationship between mental health literacy, personal contacts and personal stigma against depression. J Affect Disord. 2008;110(1–2):191–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2008.01.005.

Singh S, Zaki RA, Farid NDN. A systematic review of depression literacy: knowledge, help-seeking and stigmatising attitudes among adolescents. J Adolesc. 2019;74:154–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.06.004.

Mohr DC, Ho J, Duffecy J, Baron KG, Lehman KA, Jin L, et al. Perceived barriers to psychological treatments and their relationship to depression. J Clin Psychol. 2010;66(4):394–409. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20659.

Dennis C-L, Falah-Hassani K, Shiri R. Prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2017;210(5):315–23. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.116.187179.

Beck CT. Predictors of postpartum depression: an update. Nurs Res. 2001;50(5):275–85. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-200109000-00004.

O'Hara MW, Swain AM. Rates and risk of postpartum depression—a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry. 1996;8(1):37–54. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540269609037816.

Robertson E, Grace S, Wallington T, Stewart DE. Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: a synthesis of recent literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004;26(4):289–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.02.006.

Rubertsson C, Wickberg B, Gustavsson P, Rådestad I. Depressive symptoms in early pregnancy, two months and one year postpartum-prevalence and psychosocial risk factors in a national Swedish sample. Arch Women’s Mental Health. 2005;8(2):97–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-005-0078-8.

Beck CT. Postpartum depression: it isn’t just the blues. AJN The Am J Nurs. 2006;106(5):40–50. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000446-200605000-00020.

Finkelstein J, Lapshin O. Reducing depression stigma using a web-based program. Int J Med Inform. 2007;76(10):726–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2006.07.004.

Logsdon MC, Barone M, Lynch T, Robertson A, Myers J, Morrison D, et al. Testing of a prototype web based intervention for adolescent mothers on postpartum depression. Appl Nurs Res. 2013;26(3):143–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2013.01.005.

Jones A. Help seeking in the perinatal period: a review of barriers and facilitators. Soc Work Public Health. 2019;34(7):596–605. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371918.2019.1635947.

Poreddi V, Thomas B, Paulose B, Jose B, Daniel BM, Somagattu SNR, et al. Knowledge and attitudes of family members towards postpartum depression. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2020;34(6):492–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2020.09.003.

Pawils S, Metzner F, Wendt C, Raus S, Shedden-Mora M, Wlodarczyk O, et al. Patients with postpartum depression in gynaecological practices in Germany–results of a representative survey of local gynaecologists about diagnosis and management. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2016;76(8):888–94. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-103326.

Evans MG, Phillippi S, Gee RE. Examining the screening practices of physicians for postpartum depression: implications for improving health outcomes. Womens Health Issues. 2015;25(6):703–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2015.07.003.

Osma J, Barrera AZ, Ramphos E. Are pregnant and postpartum women interested in health-related apps? Implications for the prevention of perinatal depression. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2016;19(6):412–5. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2015.0549.

Ran M-S, Hall BJ, Su TT, Prawira B, Breth-Petersen M, Li X-H, et al. Stigma of mental illness and cultural factors in Pacific rim region: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):1–16.

Crowe M. Never good enough–part 1: shame or borderline personality disorder? J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2004;11(3):327–34.

Currid TJ. Psychological issues surrounding paternal perinatal mental health. Nurs Times. 2005;101(5):40–2.

Lioyd R, Jacob K, Patel V. The development of the short explanatory model interview (SEMI) and its use among primary care attendees with common mental disorders: a preliminary report. Psycol Med 1988;28:1231–1237. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291798007065. (Additional files).

Fischer EH, Farina A. Attitudes toward seeking professional psychologial help: a shortened form and considerations for research. J Coll Stud Dev. 1995;36(4):368–73 (Additional files).

Weinman J, Petrie KJ, Moss-Morris R, Horne R. The illness perception questionnaire: a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of illness. Psychol Health 1996;11(3):431–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870449608400270. (Additional files).

Clement S, Brohan E, Jeffery D, Henderson C, Hatch SL, Thornicroft G. Development and psychometric properties the barriers to access to care evaluation scale (BACE) related to people with mental ill health. BMC Psychiatry 2012;12(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-12-36. (Additional files).

Komiya N, Good GE, Sherrod NB. Emotional openness as a predictor of college students' attitudes toward seeking psychological help. J Couns Psychol 2000;47(1):138–143. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.47.1.138. (Additional files).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work was supported by a grant from the Damp Stiftung [grant number 2019–22]. The funding body had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, or the writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DD, SP, and BR designed the review. DD and SR were involved in the process of data extraction and synthesis. All authors provided substantial input to the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed drafts and approved the content of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Prisma 2020 Checklist.

Additional file 2.

Search Terms. This file provides an overview of the search strategy.

Additional file 3.

Quality Assessment. This file presents the critical appraisal of the included studies.

Additional file 4.

Supplemental Results. This file presents the results relating to overall levels of perinatal mental health literacy.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Daehn, D., Rudolf, S., Pawils, S. et al. Perinatal mental health literacy: knowledge, attitudes, and help-seeking among perinatal women and the public – a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 22, 574 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-04865-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-04865-y