Abstract

Background

General Practitioners (GPs) are involved in preconception, pregnancy, and postnatal care. Overall, mental health remains a significant contributor to disease burden affecting 1 in 4 pregnant women. Psychotropic medication prescribing occurs in almost 1 in 12 pregnancies, and appears to be increasing, along with the prevalence of mental health disorders in women of reproductive age. Perinatal mental health management is therefore not an unlikely scenario within their clinical practice. This scoping review aims to map current research related to GPs perceptions and experiences of managing perinatal mental health.

Method

A comprehensive search strategy using nine electronic databases, and grey literature was undertaken between December 2021 and February 2023. Relevant studies were sourced from peer review databases using key terms related to perinatal mental health and general practitioners. Search results were screened on title, abstract and full text to assess those meeting inclusion criteria and relevance to the research question.

Results

After screening, 16 articles were included in the scoping review. The majority focused on perinatal depression. Findings support that GPs express confidence with diagnosing perinatal depression but report issues of stigma navigating a diagnosis. Over the last two decades, prescribing confidence in perinatal mental health remains variable with concerns for the safety profile of medication, low level of confidence in providing information and a strong reliance on personal experience. Despite the establishment of perinatal guidelines by countries, the utilisation of these and other existing resources by GPs appears from current literature to be infrequent. Many challenges exist for GPs around time pressures, a lack of information and resources, and difficulty accessing referral to services.

Conclusion

Recommendations following this scoping review include targeted perinatal education programs specific for GPs and embedded within training programs and the development of practice guidelines and resources specific to general practice that recognises time, services, and funding limitations. To achieve this future research is first needed on how guidelines and resources can be developed and best delivered to optimise GP engagement to improve knowledge and enhance patient care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mental health conditions are a common presentation for women of reproductive age and occur in over a quarter of women during the perinatal period, defined as the period from conception, through pregnancy and the year after birth [1, 2]. General Practitioners (GPs) are involved in preconception, early pregnancy care and postnatal care. They also manage the majority of patients with mental health disorders, including high prevalence disorders such as anxiety and depression, commonly with prescribed antidepressant medications [3]. More and more, GPs also manage women with severe mental illnesses who may be planning to conceive or are pregnant as part of the shared care system which exists within our community mental health care system [4].

Almost 1 in 12 pregnancies are associated with psychotropic prescribing and evidence suggests that this rate is increasing [5, 6] alongside the prevalence of mental health disorders in women of reproductive age [7]. Estimates put around 15% of women of reproductive age in the United States (US) as being prescribed antidepressant medication [8] and combined with high rates of unplanned pregnancy in the general population rates of exposure to psychotropic medication may be higher than suggested. This makes reproductive planning and psychotropic medication counselling difficult in most cases, but vital when considering strategies to maximise mental wellbeing [9]. Dealing with the scenarios of mental health, psychotropic prescribing and pregnancy is therefore likely to be a frequent encounter within general practice and one that many GPs would be familiar with.

As part of the overall comprehensive care for pregnant women with existing mental illness, including identification, psychoeducation and referral for support counselling services, prescribing practices can have a significant impact, not just on the women’s mental health in terms of risk of relapse [10], but also on the potential risks to the pregnancy and the unborn child. It is a complex issue for women and health professionals. Available evidence from the United Kingdom suggests that many women ceased taking psychotropic medication when they learn they are pregnant [11]. Research in women with anxiety and depression and medication use, suggest that GPs have a strong influence on early decision-making [12]. Any discontinuation, switching, or lowering of doses of medication during planning or in the earlier stages of pregnancy needs to be carefully considered in the context of weighing up the risks and benefits of treatment, ideally as part of a shared decision-making process. This discussion is often led by the woman’s GP, however, there is a need to explore what advice GPs give and what sources of information they use to aid this process.

Clinical practice guidelines aim to reduce risk by outlining the research literature with the latest evidence and recommendations. Over the last three decades investment into research, education and raising awareness of perinatal mental health has occurred. Countries like Australia, the United Kingdom (UK) and United States have developed resources which focus on the area of perinatal mental health to assist community members and health professionals alike including clinical practice guidelines. Further, however we need to understand how these resources and clinical practice guidelines are used by general practitioners and how GPs can best be supported in our health system to facilitate best practice to improve health outcomes for women with mental illnesses and their babies.

A scoping review was deemed the most appropriate method of assessing the literature in trying to examine broadly General Practitioner experiences of managing perinatal mental health. Scoping reviews are often used to map existing research by synthesizing the evidence within a given field in terms of its nature, features, and volume and thereby identify gaps and make recommendations for future research [13]. This method is useful when the nature of the research question is complex or heterogenous.

Method

Guidelines set out by Arksey and O’Malley [14] created the methodological framework for this review. To ensure a rigorous scoping review, five stages were adhered to: identifying the research question, identifying relevant studies, study selection, charting the data, and collating, summarizing, and reporting the result.

Identifying the research question

Our aim was to broadly explore what is known about GPs’ experiences with perinatal mental health. Further, we wished to understand aspects related to management including clinical practice or guidelines, and psychotropic prescribing. We adopted a wide approach from the outset to gain a sense of the scope of literature and identify gaps in knowledge and further areas of research. As such, the research wanted to question what is known from the existing literature of General practitioners’ (or equivalent) perceptions and experiences when managing perinatal mental health conditions.

Search Strategy

A comprehensive search strategy using nine electronic databases was undertaken between December 2021 and January 2022, with a final rerun of the search strategy completed in February 2023: GlobalHealth, PubMed, Informit Health Collection, EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Scopus, Best Practice, ClinicalKey; along with a search of alternative grey literature sources e.g., Google Scholar. No limits were set on date, language, or methodological design. The key words and derivatives were created by the authors and tailored for the specific requirements of each database (see Appendix A). Key terms were related to the perinatal period, psychotropic prescribing, best practice guidelines and mental health. The reference lists of included articles were also manually searched for any relevant research, as well as looking at articles which had cited the included articles.

Citation management

All citations were imported into a software-based reference manager EndNote. Duplicates were removed with the aid of EndNote’s software, with further duplicates removed later in the review process.

Eligibility criteria

All articles were screened in a two-stage process; titles and abstracts were screened for relevance, followed by a full-text review. If studies appeared to describe the management of mental health within the perinatal period, they were eligible for inclusion. Studies that were not written in English, and did not have an available translation, were excluded. Systematic reviews of perinatal mental health were excluded. Studies that appeared to assess general medication management within the perinatal period or general health within the perinatal period were excluded, along with studies that did not have a clear GP or equivalent role e.g., a family physician is the US equivalent of a GP. Studies that included other roles in addition to the GPs, such as psychiatrists, needed to provide a clear separation of findings to be included in the study, i.e., if researchers reported scores in aggregate, the article was excluded. Conference proceedings without full text articles were excluded. Articles that focused on the use of alternative or complementary medicines were also excluded. Article screening was completed by SS and reviewed by JF.

Data charting

To complete a narrative review and synthesis of the articles, a data charting form was created in Excel to capture relevant information needed for analysis. Characteristics of the articles were extracted by SS and reviewed independently by JF. The information captured in the form is shown in Table 1.

From the information extracted, thematic process was adopted to highlight common themes within the articles included in the scoping review. These themes would then explain what the current landscape of GP experiences is when managing perinatal mental health, while also highlighting areas where there is a lack of research or limited understanding.

Results

Overview of the current literature

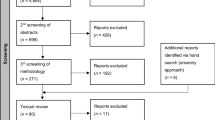

The original search was conducted over December 2021 and January 2022 and yielded a total of 1,170 potential articles. After two-stage screening, 16 articles were included in the scoping review. The flow of articles from initial identification to inclusion are represented in Fig. 1.

Of these 16 included studies, 44% were carried out in the UK, followed by 18% in Australia, including one Australian and Canadian joint study. The final six studies were undertaken in six separate locations worldwide. Methodological designs consisted of qualitative, quantitative survey and mixed methods (see Table 1). No quality appraisal of the literature was undertaken in this review, only the extent and range of the literature is presented. To ensure all recent research was captured, the literature search was conducted again in February 2023; the search yielded no new articles which detailed GPs perspectives on prescription of psychotropic medication in the perinatal period.

All studies were required to assess the experiences and perceptions of general practitioners or equivalent. However, studies within the review also assessed the perceptions of health care visitors, obstetricians and gynaecologists, women, and psychiatrists. For the purposes of this review, the focus will remain on GP experiences and responses.

The majority of the articles focused on perinatal depression [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25], depression and anxiety [26, 27], identifying psychosocial vulnerability [28], post-traumatic stress disorder [29] and overall perinatal mental health [30].

Characterisation of general practitioner’s experiences

Identification and diagnosis

The literature supports findings that GPs appear confident in the diagnosis of mental health difficulties, with particularly awareness of postnatal/perinatal depression [16] rather than other less common diagnoses [29]. GPs acknowledge that perinatal mental health was an important area [24] though not without challenges. There was reported hesitancy for some GPs to diagnose due to perceived associations with ‘labelling and stigma’ [17, 18], women’s hesitancy in seeking help or disclosing issues again reported due to a perceived lack of acceptance of a problem, stigma and the interaction between the GP and patient [16, 18, 30], and inconsistencies of how symptoms are viewed between GPs and patients. This was particularly challenging in women from Culturally and Linguistically Diverse groups [19, 30].

A biopsychosocial approach to diagnosis was used most commonly by GPs, using perceived vulnerability and instinct, risk factors including social determinants, psychiatric and somatic conditions, supportive networks and inherent resilience [17, 28] with diagnosis conceptualised using this approach [18, 30]. Although GPs liked the idea of screening tools, there appeared to be a lack of use of these formal screening tools, such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), to routinely screen women [17,18,19, 24]. These tools were seen as being more helpful in the postpartum period [24] and used more as an aid to diagnosis or as part of the referral process [30]. GPs felt that consistency of care was vital in supporting diagnosis [17,18,19, 26, 28,29,30] but also for management.

Pharmacological management

There was variability in GPs confidence in prescribing psychotropic medication. GP initiated antidepressant use in the perinatal period was high [26]. However, prescribing antidepressants as new onset in the perinatal period is viewed as second or third line in GPs, with psychological treatments and support structures taking precedence [15, 16]. This was potentially influenced by a lack of resources being available including access to care [16, 19, 21, 22, 30].

Decisions around treatment choice were influenced partially by patient factors [15] with a focus on patient centred care [30]. This was not without challenges as women were reported to stop medication abruptly on confirming a pregnancy [22]. There remained uncertainty around the safety profile of medication and low confidence in giving advice [15, 21, 22, 25, 26, 30]. Some GPs viewed treatment in pregnancy as very different compared to those who were not pregnant due to a perceived heightened vulnerability in pregnancy in general and concerns over legal liability regarding medication use in pregnancy [15, 30]. Inconsistent prescribing patterns [21, 25] were reported, with question concerning the undertreatment of women in the perinatal period [22]. The literature reported a strong reliance on GPs personal experience or experiences of colleagues in influencing their management [21, 22, 30] combined with a low use of guidelines [21, 22] to aid in prescribing practices.

Management resources

A limited knowledge of and access to educational opportunities, clinical exposure and appropriate resources impacted GPs in their practice [23, 26, 30]. Training was seen to increase the use of screening tools [24]. There was variable confidence in providing reliable information and resources to guide women in the decision making around these medications [22] and a lack of access of up to date safety data [25]. Pharmacy services were commonly used by GPs, as well as routine pharmacopeia’s, the internet [25] with often limited written information on medication provided [26], and then mainly sourced from MIMS and product information.

The limited use of guidelines corresponded to reports of GPs feeling overwhelmed by the quantity of guidelines for various medical conditions [22, 25], the lack of clear and specific direction [22, 30], often being too restrictive for individual circumstance [22], and too large in content to be useful [30].

Systems and service

Systemic limitations add difficulty. Many challenges exist for GPs around duration of consultations and how much can be covered. Perinatal mental health requires a significant time investment [16, 26] for adequate disclosure and consultation for both patients and clinicians [18]. The absence of clearly defined pathways [19] also impacts time commitment and the treatment plan. In some health systems it remains unclear where responsibility lies, and this can be compounded by issues around communication between services [20].

The overwhelming global systemic problem appears to be a lack of resources to refer patients on to [17, 19, 22, 30]. GPs generally lack trust in general psychiatric services, the prioritising of care and long wait times [29]. They would prefer to see local perinatal services [29] if they were readily available [30] but acknowledge that these services often have time limitations with care.

Discussion

Our scoping review provides an overview of what is known in the existing literature on the perception and experiences of General Practitioners when managing perinatal mental health. Most studies focused on depression in the perinatal period with limited studies existing outside of depression and anxiety. The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists [31] state that perinatal mental health includes all mental health disorders, recognising that the pregnancy and postnatal period provides a time of risk for new onset or relapse of symptoms. GPs are cognisant of the breadth of mental health disorders, with a recent Australian survey, Health of the Nation 2022 [32], stating psychological issues are one of the most common health conditions they manage.

In the literature GPs appear overall more confident in diagnosis than management, but areas of stigma for both patients and health professionals occur in disclosing and navigating a diagnosis. Two aspects discussed in this review include the use of a biopsychosocial approach and the importance of consistency of care, which are considered pillars of general practice and general practice education [33, 34]. The literature suggested that screening tools have their place in general practice but are possibly used more as an adjunct. It remains unclear if and how GPs are using these tools in their day-to-day practice currently given that the studies included in this review are over 10 years old and guidelines on screening have been introduced and updated subsequently. Consensus-based recommendations from the recently updated COPE perinatal management guidelines (2023) [35] recommend that all women should complete the EPDS preferably twice, in both the antenatal period and the postnatal period, ideally 6–12 weeks after the birth. In Australia, GPs in the vast majority are delivering postnatal care to women with potential barriers for screening existing including time limitations.

There appears to be support for using nonpharmacological therapies first line, with variation in medication prescription and use, including some strategies not supported by the evidence such as tapering of medication [15]. Delivering education is important, for both women, who were seen to cease medication abruptly on confirmation of pregnancy, consistent with studies in the literature [36], and for GPs who viewed management in pregnancy as distinct from those who are not pregnant and face uncertainty around the safety of medication. GPs disengagement with perinatal care in general is regarded as potentially leading to a deskilling in this area [27] and there are calls for a standardised GP trainee education [30] program specific to perinatal mental health.

The use of clinical or best practice guidelines in this area is reported as limited. Several countries have introduced guidelines and other resources for health professionals during the time of the studies included in this scoping review, but it is not known whether GPs are aware of, find benefit from and/or are using such resources. Clinical practice guidelines aim to reduce risk by guiding clinicians based on the research literature with the latest evidence and recommendations. A review of international clinical practice guidelines for perinatal depression, and antidepressant medication published by Molenaar et al. [3]. found the need for up-to-date and specific perinatal guidelines to help clinicians and patients in the shared decision-making process. We would propose that this needs to be specific and user friendly for GPs as they report feeling overwhelmed by the amount and volume of current guidelines for the many conditions that see within their practice.

The available literature suggests that GPs rely on personal experiences to guide them, with reliance on their own clinical experience and their colleagues. When considering GPs interaction with other health professionals, psychotropics are the leading medication class for which information on exposure during pregnancy and/or breastfeeding is requested from pharmacy services. This is in accordance with data published by other similar national and international medication information services, with requests increasing markedly since 2013 when the rate was 15.6% [37]. The consistent demand for these services despite the increasing availability of guidelines and web-based information indicates a need for clear and accessible information for prescribers, above what is provided by product information and drug categorisation in pregnancy [38], which these studies reported GPs used.

The lack of referral resources for ongoing management was a common theme in this review. A metanalysis by Ford et al. [39] in 2017 concludes that GPs remain frustrated by the lack of services and resources. It is uncertain whether the lack of resources is resulting in the undertreatment and underdiagnosis of women [17] or an increased use of prescription medication first line. Guidelines [35, 40] recommend seeking advice, preferably from a specialist in perinatal mental health particularly when initiating medication in pregnancy, but is this practical when resources are stretched? GPs are familiar with initiating pharmacological management with antidepressant and antianxiety medication [26] and would benefit from increased resources to support them in this role.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this review includes its systematic approach to identifying articles related to General Practitioners (or their equivalent) experiences around perinatal mental health more broadly and to map the research area. Limitations included the different health care services and resources available, and therefore variable experiences that occurred in differing countries. Further, the quality of literature was not appraised, therefore limiting the review to a descriptive account of GPs experiences.

Conclusions and implications for research and practice

Overall, GPs feel somewhat confident in diagnosing mental health disorders within the perinatal period. They rely on a biopsychosocial and continuity of care model. Management of these conditions becomes more challenging with many depending on clinical experience and colleagues, with a lack of resources for consultations, referral, services, and information provision. Medication is frequently initiated by GPs with limited use of guidelines.

Recommendations following this scoping review include targeted perinatal education programs specific for GPs and embedded in training programs, and the development of practice guidelines specific to general practice that recognises time, services, and funding limitations. Future research identified include the use and value of screening tools in GP, and how guidelines and resources can be developed and best delivered to optimise GP engagement to improve knowledge and enhance patient care.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Howard LM, Khalifeh H. Perinatal mental health: a review of progress and challenges. World Psychiatry. 2020;19(3):313–27.

O’Hara MW, Wisner KL. Perinatal mental Illness: definition, description and aetiology. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;28(1):3–12.

Molenaar NM, Kamperman AM, Boyce P, Bergink V. Guidelines on treatment of perinatal depression with antidepressants: an international review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2018;52(4):320–7.

Hauck Y, Nguyen T, Frayne J, Garefalakis M, Rock D. Sexual and reproductive health trends among women with enduring mental Illness: a survey of western Australian community mental health services. Health Care Women Int. 2015;36(4):499–510.

Andrade SE, Reichman ME, Mott K, Pitts M, Kieswetter C, Dinatale M, et al. Use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in women delivering liveborn infants and other women of child-bearing age within the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s Mini-sentinel program. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2016;19(6):969–77.

Epstein RA, Bobo WV, Shelton RC, Arbogast PG, Morrow JA, Wang W, et al. Increasing use of atypical antipsychotics and anticonvulsants during pregnancy. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22(7):794–801.

O’Donnell M, Anderson D, Morgan VA, Nassar N, Leonard HM, Stanley FJ. Trends in pre-existing mental health disorders among parents of infants born in Western Australia from 1990 to 2005. Med J Aust. 2013;198(9):485–8.

Dawson AL, Ailes EC, Gilboa SM, Simeone RM, Lind JN, Farr SL, et al. Antidepressant prescription claims among Reproductive-aged Women with Private Employer-Sponsored Insurance - United States 2008–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(3):41–6.

Yonkers KA. Treatment of Psychiatric conditions in pregnancy starts with planning. Am J Psychiatry. 2021;178(3):213–4.

Bayrampour H, Kapoor A, Bunka M, Ryan D. The risk of Relapse of Depression during pregnancy after discontinuation of antidepressants: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(4).

Petersen I, McCrea RL, Sammon CJ, Osborn DP, Evans SJ, Cowen PJ, et al. Risks and benefits of psychotropic medication in pregnancy: cohort studies based on UK electronic primary care health records. Health Technol Assess. 2016;20(23):1–176.

Kothari A, de Laat J, Dulhunty JM, Bruxner G. Perceptions of pregnant women regarding antidepressant and anxiolytic medication use during pregnancy. Australas Psychiatry. 2019;27(2):117–20.

Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141–6.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Bilszta JL, Tsuchiya S, Han K, Buist AE, Einarson A. Primary care physician’s attitudes and practices regarding antidepressant use during pregnancy: a survey of two countries. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011;14(1):71–5.

Buist A, Bilszta J, Barnett B, Milgrom J, Ericksen J, Condon J, et al. Recognition and management of perinatal depression in general practice–a survey of GPs and postnatal women. Aust Fam Physician. 2005;34(9):787–90.

Chew-Graham C, Chamberlain E, Turner K, Folkes L, Caulfield L, Sharp D. GPs’ and health visitors’ views on the diagnosis and management of postnatal depression: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58(548):169–76.

Chew-Graham CA, Sharp D, Chamberlain E, Folkes L, Turner KM. Disclosure of symptoms of postnatal depression, the perspectives of health professionals and women: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2009;10:7.

Edge D. Falling through the net - black and minority ethnic women and perinatal mental healthcare: health professionals’ views. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(1):17–25.

Glasser S, Levinson D, Bina R, Munitz H, Horev Z, Kaplan G. Primary Care Physicians’ attitudes toward Postpartum Depression: is it part of their job? J Prim Care Community Health. 2016;7(1):24–9.

Kean LJ, Hamilton J, Shah P. Antidepressants for mothers: what are we prescribing? Scott Med J. 2011;56(2):94–7.

McCauley C-O, Casson K. A qualitative study into how guidelines facilitate general practitioners to empower women to make decisions regarding antidepressant use in pregnancy. Int J Mental Health Promotion. 2013;15(1):3–28.

Santos Junior HP, Rosa Gualda DM, de Fatima Araujo Silveira M, Hall WA. Postpartum depression: the (in) experience of Brazilian primary healthcare professionals. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(6):1248–58.

Seehusen DA, Baldwin LM, Runkle GP, Clark G. Are family physicians appropriately screening for postpartum depression? J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18(2):104–12.

Ververs T, van Dijk L, Yousofi S, Schobben F, Visser GH. Depression during pregnancy: views on antidepressant use and information sources of general practitioners and pharmacists. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:119.

Williams S, Bruxner G, Ballard E, Kothari A. Prescribing antidepressants and anxiolytic medications to pregnant women: comparing perception of risk of foetal teratogenicity between Australian obstetricians and gynaecologists, Speciality trainees and Upskilled General practitioners. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):618.

Khan L. Falling through the gaps: perinatal mental health and general practice. Centre for Mental Health: Royal College of General Practitioners; 2015.

Brygger Veno L, Jarbol DE, Pedersen LB, Sondergaard J, Ertmann RK. General practitioners’ perceived indicators of vulnerability in pregnancy- A qualitative interview study. BMC Fam Pract. 2021;22(1):135.

Mortimer H, Habash-Bailey H, Cooper M, Ayers S, Cooke J, Shakespeare J, et al. An exploratory qualitative study exploring GPs’ and psychiatrists’ perceptions of post-traumatic stress disorder in postnatal women using a fictional case vignette. Stress Health. 2022;38(3):544–55.

Noonan M, Doody O, O’Regan A, Jomeen J, Galvin R. Irish general practitioners’ view of perinatal mental health in general practice: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):196.

RANZCP. Perinatal mental health services: The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists. ; 2021 [updated October 2021. Available from: https://www.ranzcp.org/news-policy/policy-and-advocacy/position-statements/perinatal-mental-health-services.

RACGP. General Practice Health of the Nation. 2022.

Thomas H, Best M, Mitchell G. Whole-person care in general practice: the nature of whole-person care. Australian J Gen Practitioners. 2020;49:54–60.

Wright M. Continuity of care. Australian J Gen Practitioners. 2018;47:661.

Highet N, Group atEW. Mental Health care in the Perinatal Period Australian Clinical Practice Guideline: Centre of Perinatal Excellence; 2023 [Available from: https://www.cope.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/COPE_2023_Perinatal_Mental_Health_Practice_Guideline.pdf.

Petersen I, Gilbert RE, Evans SJ, Man SL, Nazareth I. Pregnancy as a major determinant for discontinuation of antidepressants: an analysis of data from the Health Improvement Network. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(7):979–85.

Kennedy D, Eamus M, Hill M, Oei JL. Review of calls to an Australian teratogen information service regarding psychotropic medications over a 12-year period. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;53(6):544–52.

Morton AP. A to X: the problem of categorisation of Drugs in pregnancy - an Australian perspective. Comment. Med J Aust. 2012;196(3):172. author reply – 3.

Ford E, Lee S, Shakespeare J, Ayers S. Diagnosis and management of perinatal depression and anxiety in general practice: a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Br J Gen Pract. 2017;67(661):e538–e46.

NICE. Antenatal and postnatal mental health: clinical managemnt and service guidance UK: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2014 (updated 2020) [Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg192.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The researchers gratefully acknowledge Therapeutics Guidelines Ltd and the RACGP Foundation for their support of this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J. F., S. S., T. L., T. M., B.T. and T. N. assisted with project conception and development; S. S. and J. F. collected and analysed data, and all authors were involved in manuscript writing and editing. All authors critically reviewed and revised for content and gave approval to the final to be published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Frayne, J., Seddon, S., Lebedevs, T. et al. General practitioner perceptions and experiences of managing perinatal mental health: a scoping review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 23, 832 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-023-06156-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-023-06156-6